On this day on 2nd August

On this day in 1871 artist John Sloan, the son of a travelling salesman, was born in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania. His family moved to Philadelphia and after he finished high school he worked for a booksellers.

Sloan studied briefly at Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts before finding work as an artist with the Philadelphia Inquirer (1892-95). This was followed by work at the Philadelphia Press (1895-1902), where he produced full-page colour pictures based on news stories.

In 1902 Sloan moved to New York where he worked as a magazine illustrator. Sloan's paintings were also exhibited in Chicago, Pittsburgh and New York City. In 1904 he met Robert Henri and became a member of what became known as the Ash Can School, a group of artists who painted pictures of everyday urban life. Other members associated with the group included George Bellows, Rockwell Kent and Edward Hopper.

In 1910 Sloan joined the Socialist Party and the following year became art editor of the radical journal, The Masses. Although they were rarely paid, Sloan persuaded some of leading artists to provide pictures for the magazine. Artists such as Robert Henri, Stuart Davis, George Bellows, Rockwell Kent, Art Young, Boardman Robinson, Robert Minor, K. R. Chamberlain, and Maurice Becker.

Floyd Dell later recalled: "At the monthly editorial meetings, where the literary editors were usually ranged on one side of all questions and the artists on the other. The squabbles between literary and art editors were usually over the question of intelligibility and propaganda versus artistic freedom; some of the artists held a smouldering grudge against the literary editors, and believed that Max Eastman and I were infringing the true freedom of art by putting jokes or titles under their pictures. John Sloan and Art Young were the only ones of the artists who were verbally quite articulate; but fat, genial Art Young sided with the literary editors usually; and John Sloan, a very vigorous and combative personality, spoke up strongly for the artists."

Sloan was a strong supporter of woman suffrage and contributed drawing to the feminist magazines, Woman Voter and Woman's Journal. Sloan continued to work for The Masses until 1916, when he left over a dispute with Max Eastman about the captions being used with the cartoons.

John Sloan became a teacher at the Arts Students League. After the First World War Sloan moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico where he painted local people. He later recalled: "When I painted the life of the poor, I was not thinking about them like a social worker - but with the eye of a poet who sees with affection." He also contributed illustrations to Collier's Magazine, Harper's Weekly and the Saturday Evening Post.

Stephen Coppel, the author of The American Scene (2008) has pointed out: "Sloan was a prolific printmaker: between 1891 and 1940 he produced some three hundred etchings. He also tried lithography, but etching remained his true medium. He wrote about printmaking, focusing upon his personal experiences of the medium. He also produced more technical notes, giving a systematic guide to etching from how to ground the plate to the choice of paper used. His influence as one of the first chroniclers of the American scene and his technical abilities as an etcher would have a profound influence upon later American artists."

Sloan autobiography, Gist of Art, was published in 1939. In his book Sloan explained that: "I have always painted for myself and made my living by illustrating and teaching. I have never made a living from my painting." In his later years Sloan became increasingly concerned with studies of the nude in the 1940s.

John Sloan died on 7th September, 1951.

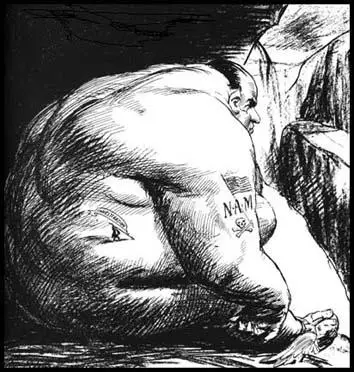

Manufacturers, The Masses (October, 1913)

On this day in 1909 Mabel Capper, together with Mary Leigh, Emily Wilding Davison, Jennie Baines, Alice Paul, and several others were charged with obstructing the police, and Lucy Burns also charged with assaulting Chief Inspector William Fraser, while disrupting a meeting at the Edinburgh Castle, Limehouse, addressed by David Lloyd George. Capper was found guilty and sentenced to 21 days imprisonment. Capper went on hunger strike and was released after six days.

On this day in 1912 Votes for Women report on the arrest of Helen Craggs for arson. Craggs and another woman were found by P.C. Godden at one o'clock in the morning outside the country home of the colonial secretary Lewis Harcourt. He went towards them and asked them what they were doing. Craggs, said they were looking round the house. The policeman said, "This is not a very nice time for looking round a house. How did you come here? Where do you come from?" Craggs said that they had been camping in the neighbourhood. The police-constable said he had not seen any encampment. She then said they had arrived by the river. Godden seized Miss Craggs and arrested her, and she was taken into custody.

Helen Craggs appeared at Bullingdon Petty Sessions the next day. According to Votes for Women, "Miss Craggs, who carried a bunch of flowers in the colours, was evidently the centre of much sympathy from the public in the Court." Helen pleaded guilty to the charge of "being in the garden…. For an unlawful purpose, to commit a felony, to unlawfully and maliciously set fire to a house and building belonging to Mr Harcourt". The judge argued that because of the seriousness of the crime - eight people were asleep in the house - bail was refused.

The police suspected that the other woman was Ethel Smyth. She was arrested the next day but was released as "she was able without difficulty to satisfy the Bench completely as to her movements on the night in question." (18) Over fifty years later Norah Smyth confided the truth to her nephew, former diplomat Kenneth Isolani Smyth, that she was with Helen Craggs in the attempt to set fire to Harcourt's house. "He expressed surprise, knowing her love of old paintings and antiques, but Smyth explained that she knew the east wing of the house was uninhabited. It was the only violent action that she undertook as a suffragette."

At her trial it was revealed that a typewritten statement was found in her handbag: "Sir, it is with a deep sense of my responsibility and a sincere conviction that my action is justifiable that I have taken a serious step in the cause of women's enfranchisement… I deplore that though during the past six years the demand for political liberty for women has become the greatest agitation of the time, politicians were content to see the supporters violently treated and unjustly imprisoned rather than give them the long-delayed and much-needed measure of justice which they demanded."

It was claimed that the women were carrying a basket and a satchel. These contained "a bottle and two cans, which contained nearly three pounds of inflammable oil, four tapers, two boxes of matches, twelve fire-lighters, nine picklocks, an electric torch, a glass-cutter, and thirteen keys."

Helen Craggs was sentenced to serve nine months with hard labour in Holloway. She went on hunger strike and was force-fed five times over two days. Her health was extremely bad and she was released after eleven days, suffering from internal and external bruising. In 1913 she went to Dublin to train as a midwife and a year later married Dr Alexander McCombie, who was working in the East End of London.

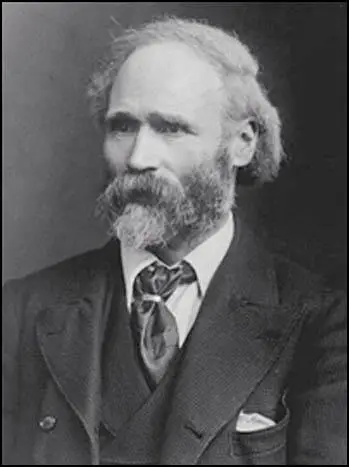

On this day in 1914 Keir Hardie makes sppech opposing involvement in First World War: "The long-threatened European war is now upon us. You have never been consulted about this war. The workers of all countries must strain every nerve to prevent their Governments from committing them to war. Hold vast demonstrations against war, in London and in every industrial centre. There is no time to lose. Down with the rule of brute force! Down with war! Up with the peaceful rule of the people!"

Hardie disagreed with many members of the Labour Party over this issue. Hardie was a pacifist and tried to organize a national strike against Britain's participation in the war. Despite being seriously ill, Hardie took part in several anti-war demonstrations and as a result some of his former supporters denounced him as a traitor. One supporter of the war asked Hardie: "Where are your two boys?" Hardie replied that he would rather see them put against a wall and shot than see them go to war."

J. R. Clynes was one of his many friends who refused to support Hardie's anti-war stance: "Hardie became a broken man. For the next twelve months the old dominant figure we had known was seen no more in the corridors of the House of Commons; he shrank into a travesty of his former self, never spoke in debates and said little to anyone. The great leader of Labour was dying on his feet. We all loved and respected him; it was a great grief to us that our attitude to war was driving the sword into his heart; but between our conscience and our friend there was only one choice." (55)

In December, 1914, Hardie had a stroke. He returned to the House of Commons in February, 1915, but he had not made a full-recovery and his friend, John Bruce Glasier, reported that he kept falling asleep during meetings. Another friend said that Hardie began suffering from delusions.

Sylvia Pankhurst later recalled: "I knew that Keir Hardie had been failing in health since the early days of the war. The great slaughter, the rending of the bonds of international fraternity, on which he had built his hopes, had broken him. Quite early he had a stroke in the House of Commons after some conflict with the jingoes. When he left London for the last time he had told me quietly that his active life was ended, and that this was forever farewell, for he would never return. In his careful way he arranged for the disposal of his books and furniture and gave up his rooms, foreseeing his end, and fronting it without flinching or regret." (56)

James Keir Hardie returned to Scotland and died in hospital in Glasgow on 25th September, 1915.

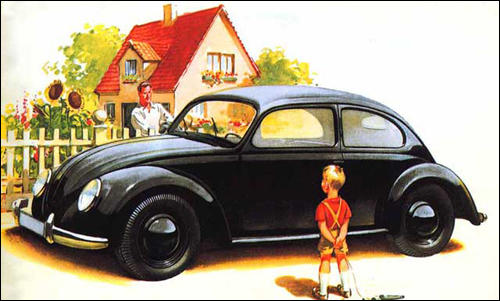

On this day in 1938 Robert Ley, the leader of German Labour Front, promises a Volkswagen car "for every German". He also gave details of how workers could obtain this new car. "I herewith proclaim the conditions under which every working person, can acquire an automobile. (i) Each German, without distinction of class, profession, or property can become the purchaser of a Volkswagen. (ii) The minimum weekly payment, insurance included, will be 5 marks. Regular payment of this amount will guarantee, after a period which is yet to be determined, the acquisition of a Volkswagen. The precise period will be determined upon the beginning of production."

In contrast to universal hire-purchase practice, the scheme provided for delivery only after payment of the last installment. William L. Shirer, the author of The Rise and Fall of Nazi Germany (1959) wrote: "Dr Ley's ingenious plan was that the workers themselves should furnish the capital by means of what became known as a 'pay-before-you-get-it' installment plan - five marks a week, or if a worker thought he could afford it, ten or fifteen marks a week. When 750 marks had been paid in, the buyer received an order number entitling him to a car as it could be turned out."

A huge advertising campaign was launched to persuade workers to put aside part of their wages to save up for one, with the slogan "a car for everyone". This was a great success and over 330,000 workers applied to buy a Volkswagen car. In 1938 a factory was built at Fallersleben to produce it.

One German reported: "For a large number of Germans, the announcement of the People's Car is a great and happy surprise.... For a long time the car was a main topic of conversation in all sections of the population in Germany. All other pressing problems, whether of domestic or foreign policy, were pushed into the background for a while. The grey German everyday sank beneath notice under the impression of this music of the future. Wherever the test models of the new Strength-Through-Joy construction are seen in Germany, crowds gather around them. The politician who promises a car for everyone is the man of the masses if the masses believe his promises. And as far as the Strength-Through-Joy car is concerned, the German people do believe in Hitler's promises."

The first completed Volkswagen cars were exhibited at Munich and Vienna at the height of the Sudetenland Crisis in October 1938. Another one was presented to Adolf Hitler at the International Motor Show in Berlin on 17th February 1939. Hitler gave it to his girlfriend Eva Braun as a birthday present. It became known as the "beetle" from the rounded shape Hitler gave it in his original design.

Soon afterwards the Volkswagen factory at Fallersleben stopped making cars. Instead it turned to the manufacture of goods that would be needed by the military in the soon to start Second World War. Not a single car was produced for those 330,000 workers who had paid in their money to the German Labour Front.