The Monarchy, the Church and the Barons

Henry I only had two legitimate children (he had at least another twenty outside marriage). When his son William drowned in 1120, Henry decided to ask his barons to accept his daughter, Matilda, as the country's next ruler. The barons were not happy about this but after much discussion they accepted Henry's request. (1)

The Normans had never had a woman leader. Norman law stated that all property and rights should be handed over to men. To the Normans this meant that her husband Geoffrey Plantagent, Count of Anjou, would become their next ruler. The people of Anjou (Angevins) were considered to be barbarians by the Normans. Most Normans were unwilling to accept an Angevin ruler and when Henry died in December 1135, instead decided to help Matilda's cousin, Stephen, the son of one of the daughters of William the Conqueror, to become king. (2)

At the time of her father's death, Matilda was with her husband in Normandy. It was not until 1139 that Matilda landed in England with her army. Stephen was eventually captured at the Battle of Lincoln (February, 1141). When Matilda went to be crowned the first queen of England, the people of London rebelled and she was forced to flee from the area. Stephen's army captured Matilda's half-brother, Robert of Gloucester. An exchange of prisoners was agreed, and Stephen obtained his freedom. (3)

Matilda accepted that she would not be accepted as Queen of England. eldest son, was a possible future king. At the age of fourteen Henry arrived in England with a small band of mercenaries. His mother disapproved of this escapade and refused to help. "So with the impudence of youth he applied to the man against whom he was fighting and with characteristic generosity Stephen sent him enough money to pay off his mercenaries and go home." (4)

Stephen's disputed succession resulted in considerable disorder. A. L. Morton, the author of A People's History of England (1938), has argued that the "worst tendencies of feudalism" emerged during this period and "private wars and private castles sprang up everywhere" and "hundreds of local tyrants massacred, tortured and plundered the unfortunate peasantry and chaos reigned everywhere". Morton claims that this "taste of the evils of unrestrained feudal anarchy was sharp enough to make the masses welcome a renewed attempt of the crown to diminish the power of the nobles." (5)

Henry also fought in France, and with his father managed to capture Normandy from Stephen. Later, when Geoffrey died. Henry inherited Normandy, Maine and Anjou. To further increase his empire, Matilda looked to find him a wife. Eleanor of Aquitaine had been married to King Louis VII of France for fifteen years. However, in this time she had given birth to Marie (1145) and Alix (1150), but failed to produce a son and the marriage was annulled in March 1152. Three months later, Henry married Eleanor. He was her third cousin, and eleven years younger. The marriage also brought another large area of France under his control. (6)

In January 1153, Henry, now aged 20, surprised Stephen by crossing the channel in midwinter. The two leaders made a series of truces which were turned into a permanent peace when the death of Eustace, in August, persuaded the king to give up the struggle. (7) In December, 1153, Stephen signed the Treaty of Winchester, that stated he was allowed to keep the kingdom on condition that he adopt Henry as his son and heir. (8)

King Henry II

Stephen died in October 1154, and Henry became king. He took over without difficulty and it was the first undisputed succession to the throne since William the Conqueror took power in 1066. Henry II was the most powerful ruler in Western Europe with an empire which "stretched from the Scottish border to the Pyrenees... but it is important to remember that although England provided him with great wealth as well as a royal title, the heart of the empire lay elsewhere, in Anjou, the land of his fathers." (9)

From an early age Henry had been trained as the next king of England. Queen Matilda had employed the best scholars in Europe to educate her son. Henry was a willing student and never lost his love of learning. One of his close friends said that Henry had a tremendous memory and rarely forgot anything he was told. When he became king he arranged for the world's best scholars to visit his court so that he could discuss important issues with them. One of his officials, Peter of Blois, commented: "With King Henry II it is school every day, constant conversation with the best scholars and discussions of intellectual problems... He does not linger in his palaces like other kings but hunts through the country inquiring into what everyone was doing, especially judges whom he has made judges of others." (10)

Henry spent many hours studying Roman history. He was particularly interested in the way Emperor Augustus had successfully managed to gain control over the Roman Empire. Henry realised that, like Augustus, his first task must be to tackle those that had the power to remove him. This meant that Henry had to control England's powerful barons. His first step was to destroy all the castles that had been built during Stephen's reign. Henry also announced that, in future, castles could only be built with his permission. The new king also deported all the barons' foreign mercenaries. (11) William of Newburgh reported: "Henry gave signs... of a strict regard for justice... In the early days he gave serious attention to public order and exerted himself to revive the laws of England, which seemed under King Stephen to be dead and buried." (12)

When Henry II became king he asked Theobald of Bec, the Archbishop of Canterbury, for advice on choosing his government ministers. On the suggestion of Theobald, Henry appointed Thomas Becket, who at the age of 34 was twelve years his senior, as his chancellor. Becket's job was an important one as it involved the distribution of royal charters, writs and letters. People declared that "they had but one heart and one mind". The king and Becket soon became close friends. "Often the king and his minister behaved like two schoolboys at play." (13)

William FitzStephen tells the story of Becket and the king riding together through the streets of London. It was a cold day and when the king noticed an old man coming towards them, poor and clad in a thin and ragged coat. "Do you see that man? How poor he is, how frail, and how scantily clad! Would it not be an act of charity to give him a thick warm cloak." Becket agreed and the king replied: "You shall have the credit for this act of charity" and then attempted to strip his chancellor of his new "scarlet and grey" cloak. After a brief struggle Becket reluctantly allowed the king to overcome him. "The king then explained what had happened to his attendants and they all laughed loudly". (14)

Henry then took action to unite the people of England. He allowed several of Stephen's officials to keep their government posts. Another strategy used by Henry was to arrange marriages between rival families. Henry was full of energy. When he was not working on government business he loved hunting. Even when he arrived back home it was said he rarely sat down. Henry, unlike most kings, cared little for appearances. He preferred hardwearing hunting clothes to royal robes. Henry also disliked the pomp and ceremony that went with being king. (15)

Contemporaries have left a vivid portrait of Henry II. According to Peter of Blois he was of medium height, with a strong square chest, and legs slightly bowed from endless days on horseback. His hair was reddish and his head was kept closely shaved. His blue-grey eyes were described as "dove-like" when in a good mood but "gleaming like fire when his temper was aroused", and flashing "like lightning" in bursts of passion. (16) Herbert of Bosham claimed that Henry had tremendous energy and was like a "human chariot dragging all after him". (17)

Once Henry had complete control over England, he turned his attention to the rest of the British Isles. In 1157 Henry forced the king of Scotland, Malcolm IV, to surrender Northumberland, Cumberland and Westmorland to England. Henry also invaded Wales and Ireland. According to Gerald of Wales, the author of The History and Topography of Ireland (c. 1190): "No one can doubt how splendidly, how vigorously, how skillfully our most excellent king has practised armed warfare against his enemies in time of war... He not only brought strong peace in England... he won victories in remote and foreign lands". (18)

Henry believed people had to earn respect. He was often rude to members of the nobility. He was quick to lose his temper and often upset important people by shouting at them. Yet, when dealing with the poor or a defeated enemy. Henry had a reputation for being polite and kind. He also had a great sense of humour and even enjoyed a joke at his own expense.

Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury

When Theobald of Bec died in 1162, Henry chose Becket as his next Archbishop of Canterbury. The decision angered many leading churchmen. They pointed out that Becket had never been a priest, and had a reputation as a cruel military comma nder when he fought against the French king Louis VII. It was claimed that "who can count the number of persons he (Becket) did to death, the number whom he deprived of all their possessions... he destroyed cities and towns, put manors to the torch without thought of pity." (19)

Becket was also very materialistic (he loved expensive food, wine and clothes). His critics also feared that as Becket was a close friend of Henry II, he would not be an independent leader of the church. At first Becket refused the post: "I know your plans for the Church, you will assert claims which I, if I were archbishop, must needs oppose." Henry insisted and he was ordained priest on 2nd June, 1162, and consecrated bishop the next day. (20)

Herbert of Bosham claims that after being appointed as archbishop, Thomas Becket began to show a concern for the poor. Every morning thirteen poor people were brought to his home. After washing their feet Becket served them a meal. He also gave each one of them four silver pennies. John of Salisbury believed that Becket sent food and clothing to the homes of the sick, and that he doubled Theobald's expenditure on the poor. (21)

Instead of wearing expensive clothes, Becket now wore a simple monastic habit. As a penance (punishment for previous sins) he slept on a cold stone floor, wore a tight-fitting hairshirt that was infested with fleas and was scourged (whipped) daily by his monks. As a contemporary wrote: "Clad in a hair-shirt of the roughest kind which reached to his knees and swarmed with vermin, he punished his flesh with the sparest diet, and his main drink was water... He often exposed his naked back to the lash." (22)

John Gillingham has argued that Becket had responded to the criticism his appointment had received: "In the eyes of respectable churchmen Becket... he did not deserve to be archbishop. He was too worldly and too much the King's friend. Wounded in his self-esteem Becket set out to prove, to an astonished world, that he was the best of all possible archbishops. Right from the start he went out of his way to oppose the King who, chiefly out of friendship, had made him an archbishop." (23)

Thomas Becket soon came into conflict with Roger of Clare, Earl of Hertford. Becket argued that some of the manors in Kent should come under the control of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Roger disagreed and refused to give up this land. Becket sent a messenger to see Roger with a letter asking for a meeting. Roger responded by forcing the messenger to eat the letter.

In January, 1163, after a long spell in France, Henry II arrived back in England. Henry was told that, while he had been away, there had been a dramatic increase in serious crime. The king's officials claimed that over a hundred murderers had escaped their proper punishment because they had claimed their right to be tried in church courts. Those that had sought the privilege of a trial in a Church court were not exclusively clergymen. Any man who had been trained by the church could choose to be tried by a church court. Even clerks who had been taught to read and write by the Church but had not gone on to become priests had a right to a Church court trial. This was to an offender's advantage, as church courts could not impose punishments that involved violence such as execution or mutilation. There were several examples of clergy found guilty of murder or robbery who only received "spiritual" punishments, such as suspension from office or banishment from the altar. (24)

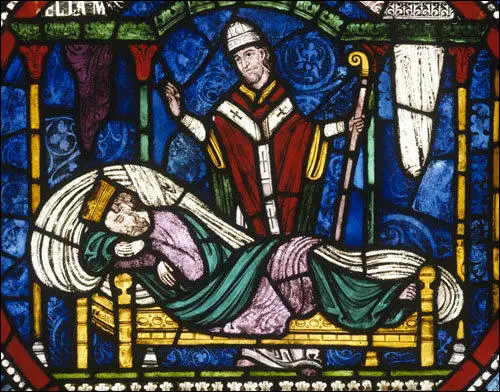

Thomas Becket in Exile

The king decided that clergymen found guilty of serious crimes should be handed over to his courts. At first, the Archbishop agreed with Henry on this issue and in January 1164, Henry published the Clarendon Constitution. After talking to other church leaders Thomas Becket changed his mind. Henry was furious when Becket began to assert that the church should retain control of punishing its own clergy. The king believed that Becket had betrayed him and was determined to obtain revenge. (25)

shows Becket denouncing the Clarendon Constitution (c.1210)

In 1164, the Archbishop of Canterbury was involved in a dispute over land. Henry ordered Becket to appear before his courts. When Becket refused, the king confiscated his property. Henry also claimed that Becket had stolen £300 from government funds when he had been Chancellor. Becket denied the charge but, so that the matter could be settled quickly, he offered to repay the money. Henry refused to accept Becket's offer and insisted that the Archbishop should stand trial. When Henry mentioned other charges, including treason, Becket decided to run away to France. (26)

Becket joined his former secretary, John of Salisbury in Rheims: The two men were very close friends: "John of Salisbury, a small and delicate man, warm, lively and playful, a joker with an eye to the ridiculous, the confident member of a learned elite, so sure of his scholarship that he could quote, to amuse his circle, classical authors and other embroideries of his own invention, was everything that Thomas Becket was not." (27)

However, the quarrel between Becket and the king put a strain upon their friendship: John would not abandon Becket's cause but he disagreed with the way Becket was dealing with the situation. (28) Becket now moved to Pontigny Abbey. According to Edward Grim, at least three times a day, his chaplain, was compelled by Becket, to "scourge him on the bare back until the blood flowed". Grim added that with these punishments he "killed all carnal desires". (29)

Under the protection of Henry's old enemy. King Louis VII, Becket organised a propaganda campaign against the monarchy. As Becket was supported by Pope Alexander III, Henry feared that he would be excommunicated (expelled from the Christian Church). Alexander sent a letter to Henry urging him to make peace with Becket and suggesting that he restored him as Archbishop of Canterbury. (30)

John of Salisbury was also involved in negotiations with Henry II and Louis VII. The three men met at Angers in April 1166. In a letter to Becket he complained that he wasted money and lost two horses on the journey and that it obtained nothing of value. (31) Talks continued and on 7th January 1169, Becket and Henry met at Montmirail but they failed to reach an agreement. Alexander, finally ran out of patience and ordered Becket to agree a deal with Henry. (32) On 22nd July, 1170, Becket and Henry met at Fréteval and it was agreed that the archbishop should return to Canterbury and receive back all the possessions of his see. (33)

Death in the Cathedral

On his arrival, Becket excommunicated (expelled from the Christian Church) Roger de Pont L'Évêque, the Archbishop of York, and other leading churchmen who had supported the king while he was away. Henry II, who was in Normandy at the time, was furious when he heard the news. Guernes de Pont-Sainte-Maxence, claims he said: "A man who has eaten my bread, who came to my court poor and I have raised him high - now he draws up his heel to kick me in the teeth! He has shamed my kin, shamed my realm: the grief goes to my heart, and no one has avenged me!" (34)

Edward Grim points out that Henry added: "What miserable drones (the male of the honeybee that is stinginess) and traitors have nourished and promoted in my realms, who let their lord to be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk." (35) According to Gervase of Canterbury the king said: "How many cowardly, useless drones have I nourished that not even a single one is willing to avenge me of the wrongs I have suffered." (36) Four of Henry's knights, Hugh de Morville, William de Tracy, Reginald FitzUrse, and Richard Ie Breton, who heard Henry's angry outburst decided to travel to England to see Becket. (37)

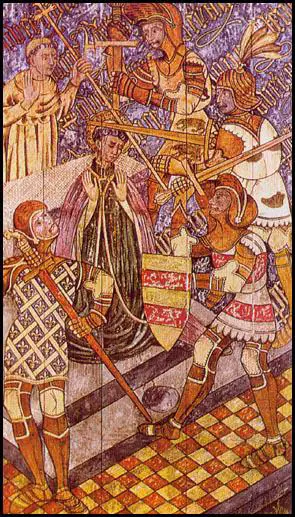

When the knights arrived at Canterbury Cathedral on 29th December 1170, they demanded that Becket pardon the men he had excommunicated. Edward Grim later reported: "The wicked knight (William de Tracy), fearing that the Archbishop would be rescued by the people in the nave... wounded this lamb who was sacrificed to God... cutting off the top of the head... Then he received a second blow on his head from Reginald FitzUrse but he stood firm. At the third blow he fell on his knees and elbows... Then the third knight (Richard Ie Breton) inflicted a terrible wound as he lay, by which the sword was broken against the pavement... the blood white with the brain and the brain red with blood, dyed the surface of the church. The fourth knight (Hugh de Morville) prevented any from interfering so the others might freely murder the Archbishop." (38)

Benedict of Peterborough, a prior based in Canterbury, wrote about what he knew about the murder: "While the body still lay on the pavement... some of them (people from Canterbury) brought bottles and carried off secretly as much blood as they could. Others cut off shreds of clothing and dipped them in the blood. Some of the blood left over was carefully collected and poured into a clean vessel... They stripped him of his outer garments... and in doing so they discovered that the body was covered in sackcloth, even from the thighs down to the knees." (39)

Saint Thomas Becket

Arnulf, the Bishop of Lisieux, was with Henry II when he heard the news of Becket's death. In a letter to Alexander III he wrote: "The king burst into loud cries and exchanged his royal robes for sackcloth... For three whole days he remained shut up in his chamber, and would neither take food nor admit anyone to comfort him." (40) William of Blois also wrote to the Pope about the murder. "I have no doubt that the cry of the whole world has already filled your ears of how the king of the English, that enemy of the angels... has killed the holy one... For all the crimes we have ever read or heard of, this easily takes first place - exceeding all the wickedness of Nero." (41)

Pope Alexander III canonised Becket on 21st February, 1173 and he became a symbol of Christian resistance to the power of the monarchy. The king met Alexander III's legates at Avranches in May and submitted to their judgment. An agreement was signed on 21st May, 1172, that included the following: "That he (Henry) should at his own expense provide two hundred knights to serve for a year with the Templers in the Holy Land. That he himself should take the cross for a period of three years and depart for the Holy Land before the following Easter. That he should utterly abolish customs damaging to the Church which had been introduced in his reign." (42)

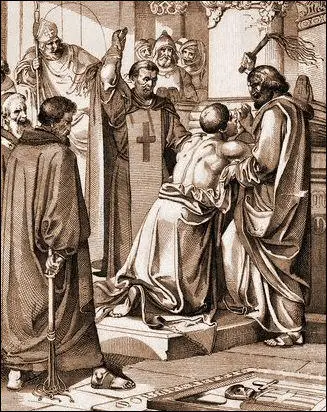

Henry admitted that, although he never desired the killing of Becket, his words may have prompted the murderers. On 12th July, 1174, Henry II did public penance, and was scourged at the archbishop's tomb. (43) The event was described by Gervase of Canterbury: "He (Henry II) set out with a sad heart to the tomb of St. Thomas at Canterbury... he walked barefoot and clad in a woollen smock all the way to the martyr's tomb. There he lay and of his free will was whipped by all the bishops and abbots there present and each individual monk of the church of Canterbury." (44)

In the Middle Ages the Church encouraged people to make pilgrimages to special holy places called shrines. It was believed that if you prayed at these shrines you might be forgiven for your sins and have more chance of going to heaven. Others went to shrines hoping to be cured from an illness they were suffering from. Becket's tomb at Canterbury Cathedral became the most popular shrine in England. When Becket was murdered local people managed to obtain pieces of cloth soaked in his blood. Rumours soon spread that, when touched by this cloth, people were cured of blindness, epilepsy and leprosy. It was not long before the monks at Canterbury Cathedral were selling small glass bottles of Becket's blood to visiting pilgrims. The monks also sold metal badges that had been stamped with the symbol of the shrine. The badges were then fixed to the pilgrim's hat so that people would know they had visited the shrine. (45)

In his discussions with Pope Alexander III, Henry agreed to allow the church courts to continue to deal with all criminal charges against clerics. The practice of "benefit of clergy" went on until the Protestant Reformation. However, as A. L. Morton pointed out: "Yet the victory of the church was not complete. The state had to surrender criminal cases: civil cases it retained. And during this period there grew up what came to be called the common law, a body of law holding good throughout the land and overriding all local laws and customs." (46)

The Magna Carta

When Henry II died in 1189, Richard the Lionheart was the eldest surviving son and therefore became king of England, Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou. "He was in England only twice for a few short months in his ten years' reign; yet his memory has always stirred English hearts, and seems to present throughout the centuries the pattern of the fighting man. Although a man of blood and violence, Richard was too impetuous to be either treacherous or habitually cruel. He was as ready to forgive as was hasty to offend." (47)

Richard the Lionheart was considered to be the best military commander in the Christian world and took part in the Third Crusade. On 8th June, 1191, Richard joined the army that had been besieging Acre for nearly two years. Saladin, the Muslim leader, attempted to take the besiegers' heavily fortified camp by storm was beaten back on 4th July. The exhausted defenders capitulated. Terms were agreed on 12th July: the garrison to be ransomed in return for 200,000 dinars and the release of 1,500 of Saladin's prisoners. (48)

N.C. Wyeth, Richard the Lionheart (1921)

On his way home in December 1192, Richard was captured by Duke Leopold of Austria. Bishop Hubert Walter immediately began negotiating terms for Richard's release. In March 1193 Bishop Walter left for England carrying letters from the captive king concerning his ransom. Among these letters was the king's command to Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine to have Hubert Walter elected archbishop of Canterbury. (49)

Over the next six months his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, helped to raise the £100,000 ransom money. "New taxes were invented and old ones revived; churches gave gold and silver vessels; a special tax of one-fourth was levied on all incomes." (59) Eleanor, who told the Pope Celestine III in a letter that she was "worn to a skeleton" made an extended visit to Germany. "This was far more than a visit of ceremony, for it had been preceded by a stream of letters concerning the conduct of government within the kingdom and the raising of the king's ransom". (50)

Richard's brother, John Lackland, decided to make a bid for power while his brother was imprisoned. Based in Windsor Castle he urged the magnates to join him in his rebellion. After summoning a council to condemn John and his followers, in February 1194 Walter himself led the successful siege of Marlborough Castle and a few weeks later he personally accepted the peaceful surrender of Lancaster Castle. (51)

Archbishop Hubert Walter urged Queen Eleanor and the regency council to adopt a conciliatory policy towards John. He was not optimistic about Richard's chances of being released and if John became king he might exact vengeance on those who had opposed or offended him. He also pointed out that John's co-operation in raising ransom money from his tenants might be needed. Eleanor and the magnates took Hubert's advice and negotiated a truce with John. He agreed to surrender his castles to his mother and if they were unable to get Richard back, he would become king. (52)

Richard was not released until 4th February, 1194. According to the chronicler Roger of Howden, King Philip II of France wrote urgently to John to tell him the news. "Look to yourself, the devil is loose." (53) Richard landed in Sandwich on 20th March, having been away for nearly four years. Ralph de Diceto wrote that three days later "to the great acclaim of both clergy and people, he was received in procession through the decorated city of London into the church of St Paul's". (54)

On 25th March 1199, Richard arrived at Châlus-Chabrol, a small castle belonging to Aimar de Limoges. While walking around the castle perimeter without his chainmail, he was struck by a crossbow bolt in the left shoulder near the neck. Mercadier, his loyal lieutenant, attempted to remove the arrow head but "extracted the wood only, while the iron remained in the flesh... but after this butcher had carelessly mangled the King's arm in every part, he at last extracted the arrow." (55)

Within a day or so the wound grew inflamed and then putrid and Richard began to suffer the effects of gangrene and blood-poisoning. Richard knew he was dying and the man who fired the arrow, Bertram de Gurdun, was brought before him. Richard asked him why "you have killed me?" He replied: "You slew my father and my two brothers with your own hand... Therefore take any revenge on me that you may think fit, for I will readily endure the greatest torments that you can devise, so long as you have met with your end, having inflicted evils so many and so great upon the world." Richard was so moved and impressed with Gurdun's speech that he ordered him to be released. (56)

Richard named John as his heir before dying on 6th April 1199. Some sources claim that Mercadier took revenge on Gurdun and "first flayed him alive, then had him hanged". (57) However, Frank McLynn, the author of Lionheart & Lackland: King Richard, King John and the Wars of Conquest (2006) has pointed out that one source argues that Mercadier sent Gurdun to Richard's sister Joan, "who put him to death in some gruesome way." (58)

King John

Hubert Walter, the Archbishop of Canterbury, died on 13th July 1205. King John decided that he had the right to appoint his replacement. He selected John de Grey, the Bishop of Norwich, who was an experienced legal clerk, judge and diplomat who had previously served as John's secretary. The chapter of clerics at Canterbury, claimed they had the right to elect the new archbishop. They opposed Grey in favour of their own man, Reginald. (59)

When news reached Pope Innocent III in Rome he was outraged. He believed strongly that he had ultimate sovereignty over Europe's kings. The Pope overturned Gray's election in March 1206. He also rejected Reginald's candidacy and put forward his own candidate, Cardinal Stephen Langton, who was a theologian and completely loyal member of the Church hierarchy. Langton was consecrated by the Pope on 17th June 1207. (60)

King John reacted by sending a letter to the Pope where he threatened to stop the papacy from using English ports. He followed this up with declaring "Langton an enemy of the Crown, and took the possessions of the See of Canterbury into royal custody." Innocent III responded on 23rd March 1208, by placing the whole of England under Interdict. This meant that all church services were forbidden to be held. (61) He also decreed that anyone calling Langton archbishop was guilty of high treason. (62)

The following year he excommunicated King John and offered negotiations to deal with the problem. However, John refused and all churches remained closed. John now seized the estates of the clergy and many of the bishops fled from the kingdom. It is being claimed that this was worth about 20,000 marks a year. Hostility towards King John increased and Roger of Wendover, a monk from St Albans Abbey, announced that he had "a vision has revealed to me that the king shall not rule more than fourteen years, at the end of which time he will be replaced by someone more pleasing to God." (63)

In 1211 the Pope declared that unless the King "would submit he would issue a bull absolving his subjects from their allegiance, would depose him from his throne, and commit the execution of the mandate to Philip of France." (64) As the result of these comments Philip II of France announced an invasion of England in April 1213. John stationed a large army in Kent but on 15th May, he decided to surrender his kingdom to the papacy and promised to pay an annual tribute of 1,000 marks. Many people saw this as a humiliating servitude, but others have praised John for carrying out a master stroke of diplomacy. "Although negotiations over payment of compensation meant that not until July 1214 was the interdict finally lifted, it none the less immediately converted Innocent into his most ardent defender and so - much to Langton's disquiet - John was able to promote his own clerks to vacant bishoprics". (65)

King John now decided to make another attempt at gaining control on his lost territory in France. In February 1214, he sailed from Portsmouth for La Rochelle, in a ship carrying numerous English nobles, as well as Queen Isabella of Angoulême and their five-year-old son, Richard. The campaign began well and his soldiers seized Poitou, Nantes and Angers. However, he suffered defeats at Roche-au-Moine (2nd July) and Bouvines (27th July). King John was forced to sign a five-year truce with King Philip at a price that was believed to be in the region of £40,000. (66)

The Magna Carta

King John returned to England as a discredited monarch. The only patch of territory in mainland France that remained loyal to the English Crown was Gascony and the area around Bordeaux. The historian, Frank McLynn, has argued that his military defeat in France caused John serious problems: "Having given up (or been forced to give up) their Norman lands, the new barons domiciled in England had more time to concentrate on the affairs of the island, with unpleasant consequences for John." (67)

When John tried to obtain this money by imposing yet another tax, the barons rebelled. Few barons remained loyal, and in most areas of the country, John had very little support. In January 1215 the king met his opponents at London - they came armed - and it was agreed that there should be another meeting in the near future. On 15th June, 1215, at Runnymede, King John was forced to accept the peace terms of his opponents. (68) As one historian pointed out: "The leaders of the barons in 1215 groped in the dim light towards a fundamental principle. Government must henceforward mean something more than the arbitrary rule of any man, and custom and the law must stand even above the King." (69)

The document the king was obliged to sign was the Magna Carta. In this charter the king made a long list of promises, including: (I) The English Church shall be free... freedom of elections, which is reckoned most important and very essential to the English Church. (II) If any of our earls, or barons... shall have died, and at the time of his death his heir shall be of full age... he shall have his inheritance. (VII) A widow, after the death of her husband, shall without difficulty have her inheritance. (VIII) No widow shall be compelled to marry, so long as she prefers to live without a husband. (XII) No scutage or aid (tax) shall be imposed on our kingdom, unless by common counsel of our kingdom. (XIV) And for obtaining the common counsel of the kingdom before the assessing of an aid or of a scutage, we will cause to be summoned the archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls, and greater barons."

Most of the terms of the charter dealt with the rights of the barons and those who were wealthy. However, there were some clauses that concerned ordinary people: (XX) "A freeman shall not be fined for a slight offence... and for a grave offence he shall be fined in accordance with the gravity of the offence... and a villein should be fined in the same way. (XXIII) No village or individual shall be compelled to make bridges or river banks. (XXX) No sheriff or bailiff... or other person, shall take the horses or carts of any freeman for transport duty, against the will of the said freeman. (XXXIX) No freeman shall be taken or imprisoned or outlawed or exiled or in anyway destroyed... except by the lawful judgement of his peers or by the law of the land. (XL) To no one will we sell, to no one will we refuse justice. (XLII) It shall be lawful in future for anyone to leave our kingdom... excepting those imprisoned or outlawed in accordance with the law in the kingdom." (70)

In July 1215, King John secretly wrote to Pope Innocent III asking him to annul the charter. Early in September the arrival of papal letters excommunicating the rebels, gave him the confidence to declare war on the Barons. He now denounced the charter and his troops laid siege to Rochester Castle. The rebels responded by offering the throne to Prince Louis, the young son of Philip II of France. In May 1216 Prince Louis invaded and made an unopposed entry into London. (71)

King John died of dysentery on 19th October 1216. His son Henry was only nine-years-old and the supporters of Louis quickly deserted to the young prince. He was crowned, and the government was carried on in his name by a group of barons led by William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke. They made sure that the principles of the Magna Carta came to be accepted as the basis of the law. (72)