The Birth of Capitalism: Richard Arkwright and Robert Owen

The first signs of capitalism began in the 15th century when the country began to move from being a producer of wool to being a manufacturer of cloth. As A. L. Morton, the author of A People's History of England (1938) has pointed out: "Though employing far fewer people than agriculture, the clothing industry became the decisive feature of English economic life, what which marked it off sharply from that of most other European countries and determined the direction and speed of its development." (1)

During this period most of the cloth was produced in the family home and therefore became known as the domestic system. (2) There were three main stages to making cloth. Carding was usually done by children. This involved using a hand-card that removed and untangled the short fibres from the mass. Hand cards were essentially wooden blocks fitted with handles and covered with short metal spikes. The spikes were angled and set in leather. The fibres were worked between the spikes and, be reversing the cards, scrapped off in rolls (cardings) about 12 inches long and just under an inch thick. (3)

The mother turned these cardings into a continuous thread (yarn). The distaff, a stick about 3 ft long, was held under the left arm, and the fibres of wool drawn from it were twisted spirally by the forefinger and thumb of the right hand. As the thread was spun, it was wound on the spindle. The spinning wheel was invented in Nuremberg in the 1530s. It consisted of a revolving wheel operated by treadle and a driving spindle. (4)

Finally, the father used a handloom to weave the yarn into cloth. The handloom was brought to England by the Romans. The process consisted of interlacing one set of threads of yarn (the warp) with another (the weft). The warp threads are stretched lengthwise in the weaving loom. The weft, the cross-threads, are woven into the warp to make the cloth. Daniel Defoe, the author of A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724) "Among the manufacturers' houses are likewise scattered an infinite number of cottages or small dwellings, in which dwell the workmen which are employed, the women and children of whom, are always busy carding, spinning, etc. so that no hands being unemployed all can gain their bread, even from the youngest to the ancient; anyone above four years old works." (5)

The woven cloth was sold to merchants called clothiers who visited the village with their trains of pack-horses. These men became the first capitalists. To increase production they sometimes they sold raw wool to the spinners. They also sold yarn to weavers who were unable to get enough from family members. Some of the cloth was made into clothes for people living in this country. However, a large amount of cloth was exported to Europe. (6)

In 1555 Parliament became concerned by the growth in wealth of these merchants and passed legislation to deal with the problem: "For as much as the weavers of the realm have as well at this present parliament as at diverse other times complained that the rich and the wealthy clothiers do many ways oppress them, some by setting up and keeping in their houses diverse looms, and keeping and maintaining them by journeymen and persons unskilful, to the decay of a great number of weavers, their wives and households". The legislation limited the number of handlooms that a clothier might keep in his house. (7)

The Factory System

The production and export of cloth continued to grow. In order to protect the woolen cloth industry the import of cotton goods was banned in 1700. In the time of Charles II the export of woolen cloth was estimated to be valued at £1 million. By the beginning of the 18th century it was almost £3 million and by 1760 it was £4 million. However, this was all changed when James Hargreaves invented the spinning-jenny in 1764. The machine used eight spindles onto which the thread was spun from a corresponding set of rovings. By turning a single wheel, the operator could now spin eight threads at once. (8)

Richard Arkwright was a wig-maker in Bolton. Arkwright's work involved him travelling the country collecting people's discarded hair. In September 1767 Arkwright met John Kay, a clockmaker, from Warrington, who had been busy for some time trying to produce a new spinning-machine with another man, Thomas Highs of Leigh. Kay and Highs had run out of money and had been forced to abandon the project. Arkwright was impressed by Kay and offered to employ him to make this new machine.

Arkwright also recruited other local craftsman, including Peter Atherton, to help Kay in his experiments. According to one source: "They rented a room in a secluded teacher's house behind some gooseberry bushes, but they were so secretive that the neighbours were suspicious and accused them of sorcery, and two old women complained that the humming noises they heard at night must be the devil tuning his bagpipes." (9)

As the economic historian, Thomas Southcliffe Ashton, has pointed out, Arkwright did not have any great inventive ability, but "had the force of character and robust sense that are traditionally associated with his native county - with little, it may be added, of the kindliness and humour that are, in fact, the dominant traits of Lancashire people." (10)

In 1768 the team produced the Spinning-Frame and a patent for the new machine was granted in 1769. The machine involved three sets of paired rollers that turned at different speeds. While these rollers produced yarn of the correct thickness, a set of spindles twisted the fibres firmly together. The machine was able to produce a thread that was far stronger than that made by the Spinning-Jenny produced by James Hargreaves. (11)

Adam Hart-Davis has explained the way the new machine worked: "Several spinning machines were designed at about this time, but most of them tried to do the stretching and the spinning together. The problem is that the moment you start twisting the roving you lock the fibres together. Arkwright's idea was to stretch first and then twist. The roving passed from a bobbin between a pair of rollers, and then a couple of inches later between another pair that were rotating at twice the speed. The result was to stretch the roving to twice its original length. A third pair of rollers repeated the process... Two things are obvious the moment you see the wonderful beast in action. First, there are 32 bobbins along each side of each end of the water frame - 128 on the whole machine. Second, it is so automatic that even I could operate it." (12)

Arkwright needed investors to make the spinning-frame profitable. Arkwright approached a banker Ichabod Wright but he rejected the proposal because he judged that there was "little prospect of the discovery being brought into a practical state". (13) However, Wright did introduce Arkwright to Jedediah Strutt and Samuel Need. Strutt was a manufacturer of stockings and the inventor of a machine for the machine-knitting of ribbed stockings. (14) Strutt and Need were impressed with Arkwright's new machine and agreed to form a partnership. (15)

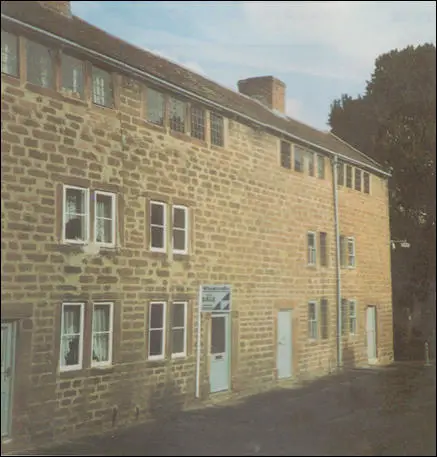

Arkwright's machine was too large to be operated by hand and so the men had to find another method of working the machine. After experimenting with horses, it was decided to employ the power of the water-wheel. In 1771 the three men set up a large factory next to the River Derwent in Cromford, Derbyshire. Arkwright later that his lawyer that Cromford had been chosen because it offered "a remarkable fine stream of water… in a an area very full of inhabitants". (16) Arkwright's machine now became known as the Water-Frame. It not only "spun cotton more rapidly but produced a yarn of finer quality". (17)

Arkwright did not build the first factory in Britain. It is believed that he borrowed the idea from Matthew Boulton, who financed the Soho Manufactory in Birmingham in 1762. However, Arkwright's factory was much larger and was to inspire a generation of capitalist entrepreneurs. According to Adam Hart-Davis: "Arkwright's mill was essentially the first factory of this kind in the world. Never before had people been put to work in such a well-organized way. Never had people been told to come in at a fixed time in the morning, and work all day at a prescribed task. His factories became the model for factories all over the country and all over the world. This was the way to build a factory. And he himself usually followed the same pattern - stone buildings 30 feet wide, 100 feet long, or longer if there was room, and five, six, or seven floors high." (18)

In Cromford there were not enough local people to supply Richard Arkwright with the workers he needed. After building a large number of cottages close to the factory, he imported workers from all over Derbyshire. Within a few months he was employing 600 workers. Arkwright preferred weavers with large families. While the women and children worked in his spinning-factory, the weavers worked at home turning the yarn into cloth. (19)

A local journalist wrote: "Arkwright's machines require so few hands, and those only children, with the assistance of an overlooker. A child can produce as much as would, and did upon an average, employ ten grown up persons. Jennies for spinning with one hundred or two hundred spindles, or more, going all at once, and requiring but one person to manage them. Within the space of ten years, from being a poor man worth £5, Richard Arkwright has purchased an estate of £20,000; while thousands of women, when they can get work, must make a long day to card, spin, and reel 5040 yards of cotton, and for this they have four-pence or five-pence and no more." (20)

Peter Kirby, the author of Child Labour in Britain, 1750-1870 (2003) has argued that it was poverty that forced children into factories: "Poor families living close to a subsistence wage were often forced to draw on more diverse sources of income and had little choice over whether their chidren worked." (21) Michael Anderson has pointed out, that parents "who otherwise showed considerable affection for their children... were yet forced by large families and low wages to send their children to work as soon as possible." (22)

The youngest children in the textile factories were usually employed as scavengers and piecers. Piecers had to lean over the spinning-machine to repair the broken threads. One observer wrote: "The work of the children, in many instances, is reaching over to piece the threads that break; they have so many that they have to mind and they have only so much time to piece these threads because they have to reach while the wheel is coming out." (23)

Scavengers had to pick up the loose cotton from under the machinery. This was extremely dangerous as the children were expected to carry out the task while the machine was still working. David Rowland, worked as a scavenger in Manchester: "The scavenger has to take the brush and sweep under the wheels, and to be under the direction of the spinners and the piecers generally. I frequently had to be under the wheels, and in consequence of the perpetual motion of the machinery, I was liable to accidents constantly. I was very frequently obliged to lie flat, to avoid being run over or caught." (24)

John Fielden, a factory owner, admitted that a great deal of harm was caused by the children spending the whole day on their feet: " At a meeting in Manchester a man claimed that a child in one mill walked twenty-four miles a day. I was surprised by this statement, therefore, when I went home, I went into my own factory, and with a clock before me, I watched a child at work, and having watched her for some time, I then calculated the distance she had to go in a day, and to my surprise, I found it nothing short of twenty miles." (25)

Unguarded machinery was a major problem for children working in factories. One hospital reported that every year it treated nearly a thousand people for wounds and mutilations caused by machines in factories. Michael Ward, a doctor working in Manchester told a parliamentary committee: "When I was a surgeon in the infirmary, accidents were very often admitted to the infirmary, through the children's hands and arms having being caught in the machinery; in many instances the muscles, and the skin is stripped down to the bone, and in some instances a finger or two might be lost. Last summer I visited Lever Street School. The number of children at that time in the school, who were employed in factories, was 106. The number of children who had received injuries from the machinery amounted to very nearly one half. There were forty-seven injured in this way." (26)

William Blizard lectured on surgery and anatomy at the Royal College of Surgeons. He was especially concerned about the impact of this work on young females: "At an early period the bones are not permanently formed, and cannot resist pressure to the same degree as at a mature age, and that is the state of young females; they are liable, particularly from the pressure of the thigh bones upon the lateral parts, to have the pelvis pressed inwards, which creates what is called distortion; and although distortion does not prevent procreation, yet it most likely will produce deadly consequences, either to the mother or the child, when the period." (27)

Elizabeth Bentley, who came from Leeds, was another witness that appeared before the committee. She told of how working in the card-room had seriously damaged her health: "It was so dusty, the dust got up my lungs, and the work was so hard. I got so bad in health, that when I pulled the baskets down, I pulled my bones out of their places." Bentley explained that she was now "considerably deformed". She went on to say: "I was about thirteen years old when it began coming, and it has got worse since." (28)

Samuel Smith, a doctor based in Leeds explained why working in the textile factories was bad for children's health: "Up to twelve or thirteen years of age, the bones are so soft that they will bend in any direction. The foot is formed of an arch of bones of a wedge-like shape. These arches have to sustain the whole weight of the body. I am now frequently in the habit of seeing cases in which this arch has given way. Long continued standing has also a very injurious effect upon the ankles. But the principle effects which I have seen produced in this way have been upon the knees. By long continued standing the knees become so weak that they turn inwards, producing that deformity which is called 'knock-knees' and I have sometimes seen it so striking, that the individual has actually lost twelve inches of his height by it." (29)

appeared in Trollope's Michael Armstrong (1840)

John Reed later recalled his life aa a child worker at Cromford Mill: "I continued to work in this factory for ten years, getting gradually advanced in wages, till I had 6s. 3d. per week; which is the highest wages I ever had. I gradually became a cripple, till at the age of nineteen I was unable to stand at the machine, and I was obliged to give it up. The total amount of my earnings was about 130 shillings, and for this sum I have been made a miserable cripple, as you see, and cast off by those who reaped the benefit of my labour, without a single penny." (30)

In 1775 Samuel Crompton invented a new machine a spinning mule. It was called because it was a hybrid that combined features of two earlier inventions, the Spinning Jenny and the Water Frame. The mule produced a strong, fine and soft yarn which could be used in all kinds of textiles, but was particularly suited to the production of muslins. Crompton was too poor to apply for a patent and so he sold the rights to a Bolton manufacturer. (31)

Handloom weavers were now guaranteed a constant supply of yarn, full employment and high wages. This period of prosperity did not last long. In 1785, Edmund Cartwright, the younger brother of Major John Cartwright, invented a weaving machine which could be operated by horses or a waterwheel. Cartwright began using power looms in a mill that he part-owned in Manchester. An unskilled boy could weave three and a half pieces of material on a power loom in the time a skilled weaver using traditional methods, wove only one. (32)

Adam Smith

The building of large factories marked the beginning of modern capitalism. In 1776 the moral philosopher, Adam Smith, published the world's first book on economics. In Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Smith outlined the advantages of capitalism. He claimed that the capitalist was motivated by self-interest: "He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it.... By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.... It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages" (33)

Smith argued that capitalism results in inequality. For example, he wrote about the impact poverty had on the lives of the labouring class: "It is not uncommon... in the Highlands of Scotland for a mother who has borne twenty children not to have two alive... In some places one half the children born die before they are four years of age; in many places before they are seven; and in almost all places before they are nine or ten. This great mortality, however, will every where be found chiefly among the children of the common people, who cannot afford to tend them with the same care as those of better station." (34)

To protect the poor Smith argued for government intervention: "The man whose whole life is spent in performing a few simple operations, of which the effects are perhaps always the same, or very nearly the same, has no occasion to exert his understanding or to exercise his invention in finding out expedients for removing difficulties which never occur. He naturally loses, therefore, the habit of such exertion, and generally becomes as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become. The torpor of his mind renders him not only incapable of relishing or bearing a part in any rational conversation, but of conceiving any generous, noble, or tender sentiment, and consequently of forming any just judgment concerning many even of the ordinary duties of private life... But in every improved and civilized society this is the state into which the labouring poor, that is, the great body of the people, must necessarily fall, unless government takes some pains to prevent it." (35)

Adam Smith pointed out the dangers of a system that allowed individuals to pursue individual self-interest at the detriment of the rest of society. He warned against the establishment of monopolies. "A monopoly granted either to an individual or to a trading company has the same effect as a secret in trade or manufactures. The monopolists, by keeping the market constantly under-stocked, by never fully supplying the effectual demand, sell their commodities much above the natural price, and raise their emoluments, whether they consist in wages or profit, greatly above their natural rate." (36)

Robert Owen

In 1810 Robert Owen purchased four textile factories owned by David Dale in New Lanark for £60,000. Under Owen's control, the Chorton Twist Company expanded rapidly. However, Owen was not only concerned with making money, he was also interested in creating a new type of community at New Lanark. He became highly critical of factory owners to employ young children: "In the manufacturing districts it is common for parents to send their children of both sexes at seven or eight years of age, in winter as well as summer, at six o'clock in the morning, sometimes of course in the dark, and occasionally amidst frost and snow, to enter the manufactories, which are often heated to a high temperature, and contain an atmosphere far from being the most favourable to human life, and in which all those employed in them very frequently continue until twelve o'clock at noon, when an hour is allowed for dinner, after which they return to remain, in a majority of cases, till eight o'clock at night." (37)

Owen set out to make New Lanark an experiment in philanthropic management from the outset. Owen believed that a person's character is formed by the effects of their environment. Owen was convinced that if he created the right environment, he could produce rational, good and humane people. Owen argued that people were naturally good but they were corrupted by the harsh way they were treated. For example, Owen was a strong opponent of physical punishment in schools and factories and immediately banned its use in New Lanark. (38)

David Dale had originally built a large number of houses close to his factories in New Lanark. By the time Owen arrived, over 2,000 people lived in New Lanark village. One of the first decisions took when he became owner of New Lanark was to order the building of a school. Owen was convinced that education was crucially important in developing the type of person he wanted. He stopped employing children under ten and reduced their labour to ten hours a day. The young children went to the nursery and infant schools that Owen had built. Older children worked in the factory but also had to attend his secondary school for part of the day. (39)

George Combe, an educator who was unsympathetic to Owen's views generally, visited New Lanark during this period. "We saw them romping and playing in great spirits. The noise was prodigious, but it was the full chorus of mirth and kindliness." Combe explained that Owen had ordered £500 worth of "transparent pictures representing objects interesting to the youthful mind" so that children could "form ideas at the same time that they learn words". Combe went on to argue that the greatest lessons Owen wished the children to learn were "that life may be enjoyed, and that each may make his own happiness consistent with that of all the others." (40)

The journalist, George Holyoake, became a great supporter of Owen's work in New Lanark: "At New Lanark he virtually or indirectly supplied to his workpeople, with splendid munificence and practical judgment, all the conditions which gave dignity to labour.... Co-operation as a form of social amelioration and of profit existed in an intermittent way before New Lanark; but it was the advantages of the stores Owen incited that was the beginning of working-class co-operation. His followers intended the store to be a means of raising the industrious class, but many think of it now merely as a means of serving themselves. Still, the nobler portion are true to the earlier ideal of dividing profits in store and workshop, of rendering the members self-helping, intelligent, honest, and generous, and abating, if not superseding competition and meanness." (41)

When Owen arrived at New Lanark children from as young as five were working for thirteen hours a day in the textile mills. Owen later explained to a parliamentary committee: "I found that there were 500 children, who had been taken from poor-houses, chiefly in Edinburgh, and those children were generally from the age of five and six, to seven to eight. The hours at that time were thirteen. Although these children were well fed their limbs were very generally deformed, their growth was stunted, and although one of the best schoolmasters was engaged to instruct these children regularly every night, in general they made very slow progress, even in learning the common alphabet." (42)

Owen's partners were concerned that these reforms would reduce profits. Frederick Adolphus Packard explained that when they complained in 1813 he replied: "that if he was to continue to act as managing partner he must be governed by the principles and practices." Unable to convince them of the wisdom of these reforms, Owen decided to borrow money from Archibald Campbell, a local banker, in order to buy their share of the business. Later, Owen sold shares in the business to men who agreed with the way he ran his factory. This included Jeremy Bentham and Quakers such as William Allen, Joseph Foster and John Walker. (43)

Robert Owen hoped that the way he treated children at his New Lanark would encourage other factory owners to follow his example. It was therefore important for him to publicize his activities. He wrote several books including The Formation of Character (1813) and A New View of Society (1814). In these books he demanded a system of national education to prevent idleness, poverty, and crime among the "lower orders". He also recommended restricting "gin shops and pot houses, the state lottery and gambling, as well as penal reform, ending the monopolistic position of the Church of England, and collecting statistics on the value and demand for labour throughout the country." (44)

In January 1816, Robert Owen made a speech at a meeting in New Lanark: "When I first came to New Lanark I found the population similar to that of other manufacturing districts... there was... poverty, crime and misery... When men are in poverty they commit crimes.., instead of punishing or being angry with our fellow-men... we ought to pity them and patiently to trace the causes... and endeavour to discover whether they may not be removed. This was the course which I adopted". (45)

Robert Owen sent detailed proposals to Parliament about his ideas on factory reform. This resulted in Owen appearing before Robert Peel and his House of Commons committee in April, 1816. Owen explained that when he took over the company they employed children as young as five years old: "Seventeen years ago, a number of individuals, with myself, purchased the New Lanark establishment from Mr. Dale.... I came to the conclusion that the children were injured by being taken into the mills at this early age, and employed for so many hours; therefore, as soon as I had it in my power, I adopted regulations to put an end to a system which appeared to me to be so injurious". (46)

In his factory Owen installed what became known as "silent monitors". These were multi-coloured blocks of wood which rotated above each labourer's workplace; the different coloured sides reflected the achievements of each worker, from black denoting poor performance to white denoting excellence. Employees with illegitimate children were fined. One-sixtieth of wages was set aside for sickness, injury, and old age. Heads of households were elected to sit as jurors to judge cases respecting the internal order of the community. (47)

Robert Owen came under attack from those who objected to the capitalist system of manufacturing. In August 1817, Thomas Wooler wrote an article about Owen in his radical newspaper Black Dwarf: "t is very amusing to hear Mr Owen talk of re-moralizing the poor. Does he not think that the rich are a little more in want of re-moralizing; and particularly that class of them that has contributed to demoralize the poor, if they are demoralized, by supporting measures which have made them poor, and which now continue them poor and wretched? Talk of the poor being demoralized! It is their would-be masters that create all the evils that afflict the poor, and all the depravity that pretended philanthropists pretend to regret."

Wooler went on to argue: "Let him abandon the labourer to his own protection; cease to oppress him, and the poor man would scorn to hold any fictitious dependence upon the rich. Give him a fair price for his labour, and do not take two-thirds of a depreciated remuneration back from him again in the shape of taxes. Lower the extravagance of the great. Tax those real luxuries, enormous fortunes obtained without merit. Reduce the herd of locusts that prey upon the honey of the hive, and think they do the bees a most essential service by robbing them. The working bee can always find a hive. Do not take from them what they can earn, to supply the wants of those who will earn nothing. Do this; and the poor will not want your splendid erections for the cultivation of misery and the subjugation of the mind." (48)

Robert Owen toured the country making speeches on his experiments at New Lanark. He also publishing his speeches as pamphlets and sent free copies to influential people in Britain. In one two month period he spent £4,000 publicizing his activities. In his speeches, Owen argued that he was creating a "new moral world, a world from which the bitterness of divisive sectarian religion would be banished". As one of his supporters pointed out that to argue that "all the religions of the world" to be wrong was "met by outrage". (49)

During this period Owen made about fifty visits to the philosophical anarchist and religious sceptic William Godwin, who was the husband of Mary Wollstonecraft, the author of Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792). Godwin had been a great influence on people such as Richard Price, Joseph Priestley, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron. (He fell out with Shelley when he eloped with sixteen-year-old daughter, Mary Godwin.) Over many years had argued that the evil actions of men are solely reliant on the corrupting influence of social conditions, and that changing these conditions could remove the evil in man. (50)

On 14th August 1817, Robert Owen addressed an audience of many hundreds at the City of London tavern. Leading members of the clergy and government were present. So also were political economists and significant figures in the reform movement. Owen called for Parliament to pass legislation to protect the poor. He also advocated an increase in taxation in order to increase public spending. (51)

Robert Wedderburn, the son of a slave, and one of the leaders of the revolutionary organisation, Society of Spencean Philanthropists, and Henry 'Orator' Hunt, accused Owen of being manipulated by the government in order to deflect working-class attention from political reform. He was also attacked by economists such as David Ricardo who said he was "completely at war with Owen" over his views on government intervention in trade and industry. (52)

A second meeting took place on 21st August, Owen rounded on all teachers of religion as having made man "a weak, imbecile animal; a furious bigot and fanatic; or a miserable hypocrite". His audience, Owen later recalled, was "thunderstruck". A few clergymen hissed but according to one newspaper, "the loudest cheers" took place when condemned the "vices of existing religious establishments". (53)

Owen's criticisms of religion caused much distress, including reformers such as William Wilberforce and William Cobbett. It also upset one of his business partners, William Allen, who was a devout Quaker. As his biographer, Leslie Stephen, has pointed out, Allen was "alarmed by Owen's avowed atheism" and eventually succeeded "in enforcing biblical instruction in the New Lanark schools, and in banning the teaching of singing, dancing, and drawing". (54)

The Father of Socialism

Over the next few years Robert Owen developed political views that has resulted in him being described as the "father of socialism". In the Report to the County of Lanark (1821) suggested that in order to avoid fluctuations in the money supply as well as the payment of unjust wages, labour notes representing hours of work might become a superior form of exchange medium. This was the first time that Owen "proclaimed at length his belief that labour was the foundation of all value, a principle of immense importance to later socialist thought". (55)

Disappointed with the response he received in Britain, Owen decided in 1825 to establish a new community in America based on the socialist ideas that he had developed over the years. Owen purchased the town of Harmony in Indiana from George Rapp for £24,000. Rapp was the leader of a religious group called the Harmonists (German Lutherans) Owen called the community he established there, New Harmony. (56)

Robert Owen explained in a letter to William Allen that he was convinced that America was an excellent place to establish his socialist community: "The principle of union and co-operation for the promotion of all the virtues and for the creation of wealth is now universally admitted to be far superior to the individual selfish system and all seems prepared or are rapidly preparing to give up the latter and adopt the former. In fact the whole of this country is ready to commence a new empire upon the principle of public property and to discard private property and the uncharitable notion that man can form his own character as the foundation and root of all evil." (57)

By 1827 Owen had lost interest in his New Lanark textile mills and decided to sell the business. His four sons and one of his daughters, Jane, moved to New Harmony and made it their permanent home. Robert Dale Owen became the leader of the new community in America. Another son, William Owen, admitted that the town often attracted the wrong people. "I doubt whether those who have been comfortable and content in their old mode of life, will find an increase of enjoyment when they come here. How long it will require to accustom themselves to their new mode of living, I am unable to determine." (58)

Owen attempted to set up Owenite villages in England. Over the next twenty years he established seven communities, the largest being at Orbiston in Scotland and at East Tytherly in Hampshire. John F. Harrison, the author of The Common People (1984) points out that "Owenism" was the main British variety of what Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels called utopian socialism. "The Owenites believed that society could be radically transformed by means of experimental communities, in which property was held in common, and social and economic activity was organized on a cooperative basis. This was a method of effecting social change which was radical, peaceful and immediate." (59)

George Holyoake became an Owenite Missionary and claimed that he was the most important political thinker since Thomas Paine. In his autobiography, Sixty Years of an Agitator's Life (1892) Holyoake explained why Owen was so important: "Just as Thomas Paine was the founder of political ideas among the people of England, Robert Owen was also the founder of social ideas among them. He who first conceives a new idea has merit and distinction; but he is the founder of it who puts it into the minds of men by proving its practicability. Mr. Owen did this at New Lanark, and convinced numerous persons that the improvement of society was possible by wise material means.... Owen gave social ideas form and force. His passion was the organization of labour, and to cover the land with self-supporting cities of industry, in which well-devised material condition should render ethical life possible, in which labour should be, as far as possible, done by machinery, and education, recreation, and competence should be enjoyed by all. Instead of communities working for the world, they should work for themselves, and keep in their own hands the fruit of their labour; and commerce should be an exchange of surplus wealth, and not a necessity of existence. All this Owen believed to be practicable." (60)

Henry Hetherington was another devoted follower of Robert Owen's political and religious beliefs: "I consider priestcraft and superstition the greatest obstacle to human improvement and happiness. I have ever considered that the only religion useful to man consists exclusively of the practice of morality, and in the mutual interchange of kind actions. In such a religion there is no room for priests and when I see them interfering at our births, marriages and deaths pretending to conduct us safely through this state of being to another and happier world, any disinterested person of the least shrewdness and discernment must perceive that their sole aim is to stultify the minds of the people by their incomprehensible doctrines that they may the more effectively fleece the poor deluded sheep who listen to their empty babblings and mystifications.... The scrambling, selfish system; a system by which the moral and social aspirations of the noblest human being are nullified by incessant toil and physical deprivations; by which, indeed, all men are trained to be either slaves, hypocrites or criminals. Hence my ardent attachment to the principles of that great and good man Robert Owen." (61)

Grand National Trade Union

Ralph Miliband has argued that Owen's political ideas would never be successful: "His insistence upon the futility of political agitation, his belief in the need to rely upon the enlightened benevolence of the governing orders, and his advocacy of a union between rich and poor made it impossible for him to play a central part in the movement of protest which followed the end of the wars. Above all, Owen's distrust of the 'industrialised poor' and his inveterate conviction that their independent action must inevitably lead to anarchy and chaos denied him the support of those leaders of labour who... came to believe that the political organization of the people was the key to social progress." (62)

Socialists such as Owen were very disappointed by the passing of the 1832 Reform Act. Voting in the boroughs was restricted to men who occupied homes with an annual value of £10. There were also property qualifications for people living in rural areas. As a result, only one in seven adult males had the vote. Nor were the constituencies of equal size. Whereas 35 constituencies had less than 300 electors, Liverpool had a constituency of over 11,000. Owen now realised that he would have to develop more radical methods to obtain social change. (63)

Robert Owen gave his support to Michael Sadler in his attempts to reduce the hours worked by children. On 16th March 1832 Sadler introduced legislation that proposed limiting the hours of all persons under the age of 18 to ten hours a day. He argued: "The parents rouse them in the morning and receive them tired and exhausted after the day has closed; they see them droop and sicken, and, in many cases, become cripples and die, before they reach their prime; and they do all this, because they must otherwise starve. It is a mockery to contend that these parents have a choice. They choose the lesser evil, and reluctantly resign their offspring to the captivity and pollution of the mill." (64)

The vast majority of the House of Commons were opposed to Sadler's proposal. However, in April 1832 it was agreed that there should be another parliamentary enquiry into child labour. Sadler was made chairman and for the next three months a parliamentary committee, that included John Cam Hobhouse, Charles Poulett Thompson, Robert Peel, Lord Morpeth, and Thomas Fowell Buxton interviewed 89 witnesses.

On 9th July Michael Sadler discovered that at least six of these workers had been sacked for giving evidence to the parliamentary committee. Sadler announced that this victimisation meant that he could no longer ask factory workers to be interviewed. He now concentrated on interviewing doctors who had experience treating people who worked in textile factories. In the 1832 General Election, Sadler lost his seat to John Marshall, the Leeds flax-spinning magnate. (65)

Parliament did pass 1833 Factory Act, but it disappointed the reformers. As R. W. Cooke-Taylor "The working day was to start at 5.30 a.m. and cease at 8.30 p.m. A young person (aged thirteen to eighteen) might not be employed beyond any period of twelve hours, less one and a half for meals; and a child (aged nine to thirteen) beyond any period of nine hours." This was much more limited than many trade unionists had hoped. (66)

Owen was so disappointed with this legislation that in November 1833 he joined John Doherty, leader of the Lancashire cotton spinners, and John Fielden, the mill owner and MP for Todmorden, to establish the National Regeneration Society. Its main object was the eight hour day in factories. (67)

Robert Owen now came to the conclusion that the only way forward was through the trade union movement. He called for the establishment of a single body of trade unionists in Britain. In October 1833 he wrote that "national arrangements shall be formed to include all the working classes in the great organisation". (68)

The first meeting of the Grand National Consolidated Trade Union (GNCTU) took place on 13th February, 1834. Within a few weeks the organisation had gained over 1,500,000 members. James Morrison, the editor of Pioneer, the official paper of the GNCTU, wrote: "our little snowballs have all been rolled together and formed into a mighty avalanche". (69)

Owen hoped it would be possible to use the GNCTU to peacefully supplant capitalism. A. L. Morton, the author of A People's History of England (1938) argues that once the GNCTU "had been formed, strikes broke out everywhere, making demands on its resources that it had no means of meeting and at the same time scaring the government into a belief that the revolution was at hand." The government decided to fight back and six farm labourers at Tolpuddle were charged with administering illegal oaths and sentenced to transportation. Over 100,000 people demonstrated against this verdict in London but it was unable to stop the men being sent to Australia. The decline of the GNCTU was as rapid as the growth and in August 1834 it was closed down. (70)

In 1835, Robert Owen formed the Association of All Classes and All Nations (later renamed the Rational Society). Over the next five years it started over 60 branches of self-styled "socialists" concentrated in the manufacturing districts, with perhaps 50,000 flocking to weekly lectures. The society's regular paper, the New Moral World, ran for nearly eleven years (1834–45), and achieved a circulation of about 40,000 weekly at its peak. Such was his fame that in 1839 he was presented to Queen Victoria. (71)

Later that year Owen and the Rational Society attempted to create a new community called Queenwood on a 533-acre site designed for 700 members. "Owen's own vision of its creation as a symbol of his ideas also became steadily more grandiose and impractical. Much of the money collected for the community was spent on constructing, in 1842, an impressively large building with lavish fittings. Especially noteworthy was a model kitchen with a conveyor to carry food and dishes to and from the dining room which, its architect exulted, rivalled the amenities of any London hotel. This would have been a great achievement had Owen been a hotelier. Owen's defence was that the community was intended to be the standard for a superior socialist future where all would enjoy privileges the wealthy monopolized at present, nay even more, for all apartments were eventually to have central heating and cooling, hot and cold water, and artificial light. Its main building thus ought to be superior to any palace. By 1844, after over £40,000 had been spent, Queenwood bankrupted the society". (72)

Owen himself returned to America several times over the next few years. In 1846 he helped to ease tensions between Britain and the USA over a border dispute in Oregon. After consulting with Robert Peel and Lord Aberdeen he crossed the Atlantic four times in fewer than six months in an effort to solve the problem. In June he wrote "the Oregon question was finally settled and on the principle which I recommended and the details will scarcely vary from my proposals to both governments." (73)

In February 1848, revolution broke out in Paris. Although nearly 77-years-old, he raced to the French capital in an attempt to popularize his views, placarding the walls of the city with broadsheets. He also wrote several articles which was both an appeal to the nation and an offer of his services to the provisional government. Owen praised the French people for taking such action and urged them to form a government to serve as an example to the world. (74)

In one article published in Le Populaire, he explained his achievements over the previous sixty years: "I have created children's homes and a system of education with no punishments. I have improved the conditions of workers in factories. I have revealed the science by which we may bestow on the human race a superior character, produce an abundance of wealth and procure its just and equitable distribution. I have provided the means by which an education may gradually be achieved - an education equal for all, and greatly superior to that which the most affluent have hitherto been able to procure. I have come to France, bringing these insights and experience acquired in many countries, to consolidate the victory newly won over a false and oppressive system that could never have lasted". (75)