Theodor Geisel (Dr. Seuss)

Theodor Seuss Geisel, the son of Theodor and Henrietta Geisel, was born in Springfield, Massachusetts, on 2nd March, 1904. His grandfather was an emigre German cavalry officer. (1)

His father owned the Kalmbach and Geisel Brewery. However, during the First World War he was bullied because he came from a German family. (2)

Geisel was educated at Dartmouth College and at Lincoln College, University of Oxford. He also spent time at the Sorbonne. While at university he began drawing cartoons using the "Dr. Seuss" pen name. (3)

He fell in love with fellow student, Helen Palmer who was to "significantly alter the direction of his life." Marian later recalled: "Ted's notebooks were always filled with these fabulous animals. So I set to work diverting him; here was a man who could draw such pictures; he should be earning a living doing that." They married in 1927. (4) On his return to America he worked as an illustrator for Vanity Fair, Life Magazine, and Judge. He also published his first children's book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street (1937). (5)

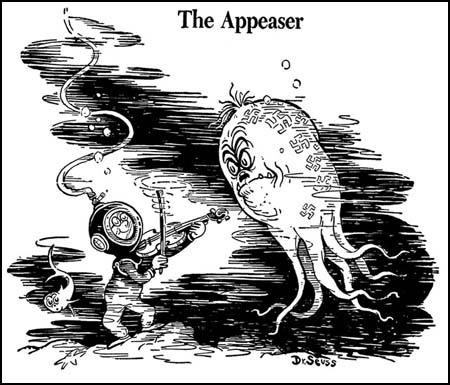

Theodor Geisel and Adolf Hitler

Theodor Geisel was very strongly opposed to the racial policies of Adolf Hitler. After the outbreak of the Second World War he joined the campaign to persuade President Franklin D. Roosevelt to give full support to the Allies. In June 1940 he became staff cartoonist for the PM newspaper. It accepted no advertising in an attempt to be free of pressure from business interests. It was decided to produce a tabloid that was the "only daily picture magazine in the world". (6) There is some confusion about why it was named PM. It has been claimed that it was an abbreviation for "Picture Magazine" or Photographic Material". (7) Another theory is that it referred to the time of day that it was printed. (8)

In its first editorial, that appeared on the front page, Ralph Ingersoll, the editor, wrote: "We are against people who push other people around" and demanded support for the Allies in the war. (9) It has been described as "one of the most controversial and unusual left-leaning American newspapers of all time." (10)

Ingersoll wrote in the first edition: "PM starts off at the most critical moment in the history of the modern world. The news is too big, too terrible to seem for a second like a break for a newspaper coming into being. Instead it dwarfs us. It pitches us, without preparation, into the midst of horror. It means that we, who wanted time to grow, shall have no youth - shall be gray-haired from birth." (11)

Other p eople who did work on the newspapers included Lillian Hellman, Dashiell Hammett, Dorothy Parker, I. F. Stone, Ben Hecht, Erskine Caldwell, Walter Winchell, Dalton Trumbo, Margaret Bourke-White, Ernest Hemingway, Donald Ogden Stewart, James Thurber, Crockett Johnson, Lillian Ross, Leo Huberman, James Wechsler, Max Lerner, Benjamin Spock, Elizabeth Hawes, Amos Landman, Leane Zugsmith, Carl Randau, Louis Kronenberger, Rae Weimer, Hodding Carter, Penn Kimball and Shirley Katzander.

The PM made use of large photographs and the cartoons of Theodor Geisel and Arthur Szyk, both strong opponents of Nazi Germany. The newspaper managed to achieve a circulation of 200,000, however, without the ability to carry advertising, it could only survive with the sponsorship of Marshall Field III, who now owned Chicago Sun, another pro-intervention newspaper. (12)

PM argued for the United States involvement in the Second World War. On 21st April, 1941, Ralph Ingersoll wrote an editorial where he gave his full support of the Allies in their war with Nazi Germany: "Others might not feel the way I do... but we have no choice but to stand against the armed expansion of Fascism, even if that stand leads to our starting to fight Hitler before he puts us in a spot in which we have to fight." (13)

America First Committee

The newspaper became a leading opponent of Charles Lindbergh and the America First Committee. (14) It was especially highly critical of speech he made in Des Moines on 11th September, 1941: "The three most important groups who have been pressing this country toward war are the British, the Jewish and the Roosevelt administration. Behind these groups, but of lesser importance, are a number of capitalists, Anglophiles and intellectuals who believe that their future, and the future of mankind, depends upon the domination of the British Empire... These war agitators comprise only a small minority of our people; but they control a tremendous influence... It is not difficult to understand why Jewish people desire the overthrow of Nazi Germany... But no person of honesty and vision can look on their pro-war policy here today without seeing the dangers involved in such a policy, both for us and for them. Instead of agitating for war, the Jewish groups in this country should be opposing it in every possible way, for they will be among the first to feel its consequences." (15)

The headline of the newspaper in response to the speech stated: "Lindbergh Lays Foundation for Fascist Revolt in U.S.A." (16) Other targets of its anger included right-wing figures such as William Randolph Hearst (whose newspapers described PM as a "Commie" rag), the leading racist and anti-Semite in Congress, John Elliot Rankin, and Father Charles Edward Coughlin. As Myra MacPherson has pointed out: "freed from advertisers, it passionately supported unions and workers' rights, including the controversial right to strike during wartime... and crusaded for an increase in the minimum wage." (17)

Thomas E. Mahl, the author of Desperate Deception: British Covert Operations in the United States, 1939-44 (1998) has argued: "PM never attracted enough circulation to make money, but it was a wonderful propaganda vehicle despite its small circulation. In September, 1940, Field bought out the other backers for twenty cents on the dollar." In a declassified report from British Security Coordination it listed PM as "among those who rendered service of particular value". (18)

In June, 1941, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Ralph Ingersoll wrote: "This is the time to keep as cool as the news and the temperature permits, to watch what happens and to remember that your President foresaw it many months ago when he warned you that this was a total war. The sudden scrapping of the world's most momentous pact is one of the things total war means. What it might mean to the USA before it is over could be just as dramatic - if we ever let anything happen to Great Britain or we take our eye - for one single moment - off our enemy, Hitler. It will not end until he is destroyed." (19)

Members of the Communist Party of the United States now became supporters of PM magazine. James Wechsler, an anti-communist member of staff complained: "When the Nazis invaded Russia in June, 1941, Ingersoll really got the old Popular Front gleam in his eye." (20)

Joseph Stalin was now portrayed in a favourable light by the newspaper. I. F. Stone wrote that "by his attack on the Soviet Union... Hitler has landed a huge anti-Nazi army on the Continent... Hitler had hoped that dislike for Stalin's ideological table manners and conversely, Soviet dislike for ours - would keep the leadership of the Western free countries from effective united action, and it may." (21)

Theodor Geisel (Dr. Seuss) produced a series of cartoons attacking Adolf Hitler and his American apologists. When the isolationist politician, Gerald Nye, endorsed the pro-Nazi magazine The Cross and the Flag, produced by Gerald L. K. Smith, he drew Nye as a horse's ass. (22)

Second World War

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the United States joined the war. James Wechsler later recalled that Ralph Ingersoll "walked about the city room in a kind of vacant trance" and finally "confessed at a staff meeting that he was no longer certain of the paper's excuse for existence. Its mission was accomplished. The nation was at war." Circulation increased to 90,000 but it was still 150,000 short of the figure estimated that was necessary to get PM into profit. (23)

Over a two year period Dr. Seuss produced over 400 cartoons. Sometimes he was accused of going too far. This included one that was published on 13th February, 1942, that suggested all Japanese Americans were latent traitors or fifth-columnists. (24) Richard H. Minear, the author of Dr. Seuss Goes to War (1999) claims that other cartoons "deplored the racism at home against Jews and blacks that harmed the war effort". (25)

In 1943 Theodor Geisel joined the United States Army as a Captain and was commander of the Animation Department of the First Motion Picture Unit, where he wrote propaganda films under the tutelage of Frank Capra. (26) One of these films, Our Job in Japan, became the basis for the commercially released film Design for Death (1947), a study of Japanese culture that won the Academy Award for Documentary Feature. (27)

Children's Books

After the war Geisel, who was described as a "irrepressible child who has no children" moved to La Jolla, California, where he concentrated on producing books for children. (28) "I'd rather write for kids," he later explained. "They're more appreciative; adults are obsolete children, and the hell with them." His books included Horton Hears a Who! (1954), The Cat in the Hat (1957), How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1957), Yertle the Tertle (1958), The Sneetches (1961), Fox in Socks (1965), Mr. Brown Can Moo! Can You? (1970). Eric Pace has pointed out: "Geisel's work delighted children by combining the ridiculous and the logical, generally with a homely moral." (29)

Helen Palmer Geisel committed suicide in 1967 with an overdose of barbiturates. She had been suffering from poor health and was also depressed by her husband's decision to leave her for Audrey Stone Dimond. In her suicide note she wrote: "Dear Ted, What has happened to us? I don't know. I feel myself in a spiral, going down down down, into a black hole from which there is no escape, no brightness. And loud in my ears from every side I hear, 'failure, failure, failure... I love you so much... I am too old and enmeshed in everything you do and are, that I cannot conceive of life without you... My going will leave quite a rumor but you can say I was overworked and overwrought. Your reputation with your friends and fans will not be harmed... Sometimes think of the fun we had all thru the years." (30)

Ted's niece Peggy commented: "Whatever Helen did, she did it out of absolute love for Ted... It was her last and greatest gift to him." In 1968, Theodor Geisel married Audrey Stone Dimond. (31)

Theodor Geisel died on 24th February, 1991.

Primary Sources

(1) Time Magazine (11th August, 1967)

Geisel, an irrepressible child who has no children, is far from obsolete. Working out of a former observation tower atop Mount Soledad, highest point in La Jolla, he carefully turns his easel away from the distraction of the panoramic Pacific view, continues to create intriguing cartoon characters, pen funny - but moralistic - stories, mainly in verse. Scarcely a grade school or children's library in the U.S. is without his books, which are used mainly to help beginning readers get a kick out of reading. Geisel once based his book texts - as most publishers of reading primers still do - on standardized basic word lists. But he now considers such lists so much hogwash, because today's television-viewing children have an expanded vocabulary, uses any word "that has to do with a child's life and hopes."

While Dr. Seuss's young readers laugh, they also learn the value of patience from Horton, who sits on a bird's egg in a tree for eleven trying months, gets his reward when he hatches an elephant-bird. Thidwick the Big-Hearted Moose is a model of kindness who lets animals ride on his horns because "a host, above all, must be nice to his guests." Geisel wrote about "star-bellied Sneetches," who thought they were better than "plain-bellied Sneetches," to score points against prejudice. He does not mind being called "the greatest moralist since Elsie Dinsmore," contends that it is both right and inevitable that "you can find a moral in anything you read."The Massachusetts-born Geisel has a B.A. degree from Dartmouth and studied at Oxford University, but has had no art training since walking out on a high-school art teacher who refused to let him draw with his drawing board turned upside down. A cartoon of egg-nog-drinking turtles that he sold to Judge magazine in 1927 financed his marriage to fellow Oxford Student Helen Palmer, who helps him develop his story lines. His career got a big boost when his advertising cartoons for an insecticide made the caption "Quick, Henry, the Flit!" a common household quip. He was a cartoonist for the New York daily PM, created the prizewinning "Gerald McBoing-Boing" movie cartoons, and has completed a book of original songs for children.

Geisel, who considers his work "logical insanity," gets a wry chuckle out of all the profound Ph.D. papers written about his books. He views himself - and most creative people - as those who "compensate for something - you wouldn't start building something new unless you were dissatisfied with what you've got." Perhaps, he adds with a smile, "we are all psychotic." Maybe so, but under the spell of Dr. Seuss, a cat that wears a hat and an elephant that sits in a tree somehow seem more normal than a Dick and Jane who chase a ball.

(2) Eric Pace, New York Times (26th September, 1991)

In Theodor Seuss Geisel, the author and illustrator whose whimsical fantasies written under the pen name Dr. Seuss entertained and instructed millions of children and adults around the world, died in his sleep on Tuesday night at his home in La Jolla, Calif. He was 87 years old.

The exact cause of death was unclear, said Jerry Harrison, who oversees children's books for Random House, Mr. Geisel's longtime publishers. Mr. Harrison said the author had been suffering from an infection of his jawbone that had become acute in recent months.

"We've lost the finest talent in the history of children's books," Mr. Harrison said in a telephone interview, "and we'll probably never see one like him again."

Mr. Geisel's work delighted children by combining the ridiculous and the logical, generally with a homely moral. "If I start out with the concept of a two-headed animal," he once said, "I must put two hats on his head and two toothbrushes in the bathroom. It's logical insanity."

Mr. Geisel's first book, "And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street," appeared in 1937. It was followed by such classics as "Horton Hatches the Egg" in 1940 and "The Cat in the Hat" in 1957.

Over the years, zany animal characters, names and book titles were the Dr. Seuss trademarks. There was "Yertle the Tertle" (1958), "Fox in Socks" (1965), "Mr. Brown Can Moo! Can You?" (1970) and others too improbable to mention.

But the archetypal Seuss hero, many connoisseurs felt, was Horton, a conscientious pachyderm who was duped by a lazy bird into sitting on her egg. Horton stuck to the job for many weeks, despite dreadful weather and other harassments, saying, "I meant what I said and I said what I meant; an elephant's faithful 100 percent." His virtue was finally rewarded when the egg hatched and out came a creature with a bird's wings and an elephant's head.

Mr. Geisel won the hearts and minds of children "by the sneaky stratagem of making them laugh," Richard R. Lingeman wrote in a review in The New York Times. He also charmed adults, especially with "Oh, the Places You'll Go!," a 1990 book he wrote for adult readers as well as children, which has been on The New York Times best-seller list for 79 weeks.

Sales of "Horton Hatches the Egg," "The Cat in the Hat" and other children's books by Mr. Geisel totaled well over 200 million copies, Kathleen Fogarty, the director of publicity for Random House Books for Young Readers, said. She said he had written 48 books in his long career, some of them meant for adults as well as children.

In 1984, he won a special Pulitzer citation "for his contribution over nearly half a century to the education and enjoyment of America's children and their parents."

(3) Time Magazine (30th July, 2015)

The 650 million children who have read Dr Seuss' books have been exposed to new ways of rethinking a social order often imbued in prejudice...

In the late 1930s, using the pen name Dr Seuss, Geisel created cockamamie ad campaigns for Flit bug spray. During the early years of World War II, he contributed notoriously vicious caricatures of the people and leaders of Axis nations for the Popular Front tabloid PM. After joining famous Hollywood director Frank Capra’s Army Signal Corps unit in 1943, he co-created propaganda films under Capra’s tutelage.

However in the years after the war, Dr Seuss’ art underwent a radical thematic shift. With a flood of eager baby boomer readers, he decided he wanted to speak to the perspective of children.

The racist caricatures of Japanese civilians and soldiers that Dr Seuss published in PM had drawn on the social prejudice and aggression that Geisel believed lay at the heart of adult humor. So Geisel entrusted Dr Seuss’ postwar art to the belief that children possessed a sense of fairness and justice that could transform their parents’ world.

Geisel described his 1954 children’s book Horton Hears a Who!, in part, as an apology to the Japanese people his propaganda had demeaned during the war. In subsequent children’s books, he began addressing the major issues of the 20th century: civil rights in The Sneetches (1961), environmental protection in The Lorax (1971) and the nuclear arms race in The Butter Battle Book (1984).

Student Activities

British Newspapers and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

Night of the Long Knives (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

The Assassination of Reinhard Heydrich (Answer Commentary)

The Last Days of Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

References

(1) Eric Pace, New York Times (26th September, 1991)

(2) Donald E. Pease, Theodor Seuss Geisel (2010) page 5

(3) Encyclopædia Britannica (2015)

(4) Donald E. Pease, Theodor Seuss Geisel (2010) page 40

(5) Eric Pace, New York Times (26th September, 1991)

(6) Myra MacPherson, All Governments Lie! The Life and Times of Rebel Journalist I. F. Stone (2006) page 196

(7) D. D. Guttenplan, American Radical: The Life and Times of I.F. Stone (2011) page 167

(8) Roy Hoopes, Ralph Ingersoll (1985) page 216

(9) Ralph Ingersoll, PM (18th June, 1940)

(10) Myra MacPherson, All Governments Lie! The Life and Times of Rebel Journalist I. F. Stone (2006) page 93

(11) Ralph Ingersoll, PM (18th June, 1940)

(12) Roy Hoopes, Ralph Ingersoll (1985) page 237

(13) Ralph Ingersoll, PM (21st April, 1941)

(14) Myra MacPherson, All Governments Lie! The Life and Times of Rebel Journalist I. F. Stone (2006) page 197

(15) Charles Lindbergh, speech in Des Moines (11th September, 1941)

(16) PM newspaper (5th October, 1941)

(17) Myra MacPherson, All Governments Lie! The Life and Times of Rebel Journalist I. F. Stone (2006) page 198

(18) Nigel West, British Security Coordination (1998) pages 55-56

(19) Ralph Ingersoll, PM (22nd June, 1941)

(20) James Wechsler, Age of Suspicion (1953) page 172

(21) D. D. Guttenplan, American Radical: The Life and Times of I.F. Stone (2011) page 174

(22) D. D. Guttenplan, American Radical: The Life and Times of I.F. Stone (2011) page 170

(23) Roy Hoopes, Ralph Ingersoll (1985) page 254

(24) Theodor Geisel, PM (13th February, 1942)

(25) Richard H. Minear, Dr. Seuss Goes to War (1999) page 191

(26) Time Magazine (30th July, 2015)

(27) Judith Morgan, Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel (1995) pages 119-120

(28) Time Magazine (11th August, 1967)

(29) Eric Pace, New York Times (26th September, 1991)

(30) Judith Morgan, Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel (1995) pages 195-198