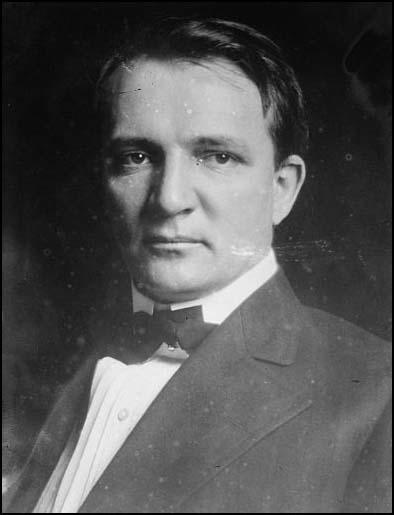

Raymond Robins

Raymond Robins, the son of Charles Ephraim Robins (1832–1893) and Hannah Maria Crow (1836–1901), was born on Staten Island on 17th September, 1873. His mother was an opera singer, was committed to an insane asylum when he was a child.

Charles Robins was an insurance broker and banker. He was also a follower of Robert Owen and held progressive political views. Raymond and his sister, Elizabeth Robins, grew up with radical political opinions. Elizabeth became an actress and in 1888 she travelled to London where she introduced British audiences to the work of Henrik Ibsen. Over the next few years Elizabeth Robins was one of the most popular actresses on the West End stage.

Robins was a rebel as a young man he worked as a coal miner in Tennessee and Colorado. He returned to education and graduated from George Washington University in 1896. Robins took part in the Klondike Gold Rush in 1897. The following year he converted to Christianity, and became pastor for a Congregational church in Nome, Alaska.

Robins was deeply influenced by Christian Socialism and in 1900 he moved to Chicago where became involved in the Hull House movement. Established by Jane Addams and Ellen Starr ten years earlier, members of the community included Florence Kelley, Edith Abbott, Grace Abbott, Alice Hamilton, Charlotte Perkins, William Walling, Charles Beard, Mary McDowell, Mary Kenney, Alzina Stevens and Sophonisba Breckinridge.

Addams recruited university teachers, students and social reformers to provide free lectures on a wide variety of different topics. Over the years this included people such as Robins, John Dewey, Clarence Darrow, Susan B. Anthony, William Walling, Robert Hunter, Robert Lovett, Ernest Moore, Charles Beard, Paul Kellogg, Jenkin Lloyd Jones, Ray Stannard Baker, Francis Hackett, Henry Demarest Lloyd and Frank Lloyd Wright.

In 1905 Margaret Dreier heard Raymond Robins deliver a lecture on the social gospel in a church in Brooklyn. Soon afterwards the couple got married. Robins was a member of the Chicago Board of Education from 1906 to 1909. He served also as social service expert for the Men and Religion Forward Movement. He was leader of the National Christian Social Evangelistic campaign in 1915.

William Hard was a close friend and he later recalled that he turned away from the socialism of his youth: "He was living then at a settlement in Chicago called the Chicago Commons. It had an open forum called, I think I remember, the Free Floor. On that Free Floor, and in little halls on North Clark Street, and in all sorts of other places, Robins and I heard all sorts of Bolshevik oratory in the Chicago of the early innocent twentieth century.... Raymond Robins' favorite intellectual pursuit was to go after it with all the arguments he could think of. In forums and in halls and at that earnest gathering of local truth-seekers called the Friday Lunch Club he never missed an opportunity to argue against Bolshevism and against every other form of Socialism."

Robins became a leading figure in the Progressive Party and served as chairman of the State Central Committee. Theodore Roosevelt and Hiram Johnson became the party's candidates in the 1912 presidential election. The proposed program included women's suffrage, direct election of senators, anti-trust legislation and the prohibition of child labour. In winning 4,126,020 votes Roosevelt defeated William H. Taft, the official candidate of the Republican Party. However, he received less votes than the Democratic Party candidate, Woodrow Wilson. In 1914, Robins was candidate for United States Senator from Illinois.

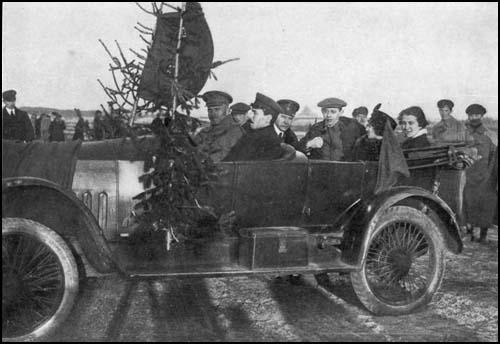

(behind the boy soldier), Alexander Gumberg, and Charles Stevenson Smith.

During the First World War he headed the expedition for the American Red Cross to Russia. After the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in March, 1917, George Lvov was asked to head the new Provisional Government in Russia. Robins was a strong supporter of Alexander Kerensky, the Minister of War. Kerensky toured the Eastern Front where he made a series of emotional speeches where he appealed to the troops to continue fighting. Kerensky argued that: "There is no Russian front. There is only one united Allied front." Leon Trotsky met him during this period and described him as a "counter-revolutionary".

It has been claimed that after the Russian Revolution Robins met Lenin on average three times a week. The two men had a series of debates on politics. On one occasion Lenin said to Robins: "We may be overthrown in Russia, by the backwardness of Russia or by foreign force, but the idea in the Russian revolution will break and wreck every political social control in the world. Our method of social control dominates the future. Political social control will die. The Russian revolution will kill it everywhere." Robins dismissed this idea of the future: "But my government is a democratic government. Do you really say that the idea in the Russian revolution will destroy the democratic idea in the government of the United States?... Our national government and our local governments are elected by the people, and most of the elections are honest and fair, and the men elected are the true choices of the voters. You cannot call the American government a bought government."

Lenin replied: "I'll tell you, our system will destroy yours because it will consist of a social control which recognizes the basic fact of modern life. It recognizes the fact that real power today is economic and that the social control of today must therefore be economic also.... This system is stronger than yours because it admits reality. It seeks out the sources of daily human work-value and, out of those sources, directly, it creates the social control of the state. Our government will be an economic social control for an economic age. It will triumph because it speaks the spirit, and releases and uses the spirit, of the age that now is. Therefore, Colonel Robins, we look with confidence at the future. You may destroy us in Russia. You may destroy the Russian revolution in Russia. You may overthrow me. It will make no difference. A hundred years ago the monarchies of Britain, Prussia, Austria, Russia, overthrew the government of revolutionary France. They restored a monarch, who was called a legitimate monarch, to power in Paris. But they could not stop, and they did not stop, the middle-class political revolution, the revolution of middle class democracy, which had been started at Paris by the men of the French Revolution of 1789. They could not save feudalism. Every system of feudal aristocratic social control in Europe was destined to be destroyed by the political democratic social control worked out by the French Revolution. Every system of political democratic social control in the world to-day is destined now to be destroyed by the economic producers' social control worked out by the Russian revolution."

While in Petrograd Robins met the British journalist, Arthur Ransome, who he met for the first time in 1918. According to Roland Chambers, the author of The Last Englishman: The Double Life of Arthur Ransome (2009): "On the day after the Trotsky interview, Ransome had dined with Colonel Raymond Robins, head of the American Red Cross, and Edgar Sisson, former editor of the Chicago Tribune. Robins, he concluded, was by far the superior specimen. As an evangelical Christian, an Alaskan gold prospector and straight-talking Chicago progressive, his politics were no more compatible with Bolshevism than those of Woodrow Wilson, whom he counted amongst his personal friends. But Robins had seen the Bolsheviks at work in the regional soviets. No other government, he believed, was capable of maintaining order at home while opposing German interests. If the Allies wanted an Eastern Front, they should supply the money and arms. If they wanted peace, it would have to be a general peace. By the time Ransome returned to Petrograd, Robins was on excellent terms with Trotsky and Lenin, whom he considered men of courage and integrity." Ransome later recalled that Robins told him that Leon Trotsky was "four times son of a bitch, but the greatest Jew since Jesus."

On 25th April, 1918, Robins had dinner with Arthur Ransome. The two men agreed that the Soviet government would survive and that Western governments should not attempt to overthrow it. Ransome argued that he had written a pamphlet with Karl Radek, entitled On Behalf of Russia: An Open Letter to America. Robins, who was just about to leave for home, agreed to use his influence to get it published by The New Republic magazine.

The pamphlet was published in July 1918. It included the following passage: "These men who have made the Soviet government in Russia, if they must fail, will fail with clean shields and clean hearts, having, striven for an ideal which will live beyond them. Even if they fail, they will none the less have written a page in history more daring, than any other which I can remember in the history of humanity. They are writing it amid the slinging of mud from all the meaner spirits in their country, in yours and in my own. But when the thing is over, and their enemies have triumphed, the mud will vanish like black magic at noon, and that page will he as white as the snows of Russia, and the writing on it as bright as the gold domes I used to see glittering in the sun when I looked from my window in Petrograd."

William Hard, the author of Raymond Robins' Own Story (1920), has argued that as a result of Robins arguing against Allied intervention in Russia in support of the White Army, he was accused of being a Bolshevik. "Today, because he opposes American and Allied military intervention in Russia, certain hasty or malevolent persons try to stamp the stigma of Bolshevism on him. I only ask: how many of those persons have ever said one word against Bolshevism where to say it was dangerous? Robins spoke against Bolshevism in Petrograd itself. He labored against Bolshevism., and is publicly recorded to have labored against it, all through the period while Russia was making its choice between Kerensky and Lenin. Robins has been consistently and continuously anti-Bolshevik, in America and in Russia; but he saw the failure of our diplomacy in Russia; and he had a chance to perceive the reason, the instructive reason.... Robins holds the view that no effort to combat Bolshevism can ever be successful unless it is directed against what Bolshevism is, instead of against what Bolshevism is not; and therefore he has first tried to describe what Bolshevism is, in its internal going power; and if people call him a Socialist for doing so, he can afford to be patient."

Hard went on to point out: "Robins came back from Russia in June of 1918, and said that in the Soviet republic there was great strength and great capacity for resistance. Other persons, much more in the confidence of the administration at Washington, came back and said that the Soviet republic was nothing but a street corner soap-box stuffed out with a German subsidy. For month after month, then, the Allies and the anti-Bolshevik Russians attacked the Soviet republic by arms on all fronts; and the Soviet republic, blockaded, starving, sick, with no conceivable help any longer from the Kaiser and with no possible access to the imported machine-materials on which Russian industrial life had always depended, for month after month held out. Tested by life, the Soviet republic was not a feeble thing. It was a powerful thing, generating its own power out of its own power-house, somewhere, somehow."

Robins continued to call for United States recognition and he was partly responsible for persuading President Franklin Roosevelt to exchange ambassadors in 1933.

Raymond Robins died on 26th September, 1954.

Primary Sources

(1) William Hard, Raymond Robins' Own Story (1920)

With Bolshevism triumphant at Budapest and at Munich, and with a Council of Workmen's and Soldiers' Deputies in session at Berlin, Raymond Robins began to narrate to me his personal experiences and his observations of the dealings of the American government with Bolshevism at Petrograd and at Moscow.

But he was not merely an observer of those dealings. He was a participant in them. Month after month he acted as the unofficial representative of the American ambassador to Russia in conversations, and negotiations with the government of Lenin.

Throughout that period he saw Lenin personally three times (on an average) a week. Incidentally, the degree of eagerness felt by the Allied and American governments to make Lenin's acquaintance and to learn his actual character and his actual purpose, good or bad, may be judged from the fact that during all those months Col. Raymond Robins of the American Red Cross was the only Allied or American officer who ever actually had personal conferences with Lenin.

Lenin speaks English fluently. He was talking one day about Russia's industrial backwardness and he made a saying which Robins now calls especially to mind.

Russia's backwardness in industry is a grave handicap to Russian Socialism. Russia is poorly prepared for the socialist experiment. Lenin knew this. Whatever else he may be, he is a man of knowledge, of great knowledge, a laborious student and scholar. He was speaking of the prospects of Socialism in Russia, and he said:

"The flame of the Socialist revolution may die down here. But we will keep it at its height till it spreads to countries more developed. The most developed country is Germany. When you see a Council of Workmen's and Soldiers' Deputies at Berlin, you will know that the proletarian world revolution is born."

We see that Council to-day, and we see Allied and American diplomacy considering it and striving, in one way and another, to deal with it. That is why Colonel Robins is especially moved to speak at this moment. He saw the diplomatic methods which failed to deal successfully with Bolshevism at Petrograd and Moscow, and he feels that he has every reason of practical experience to believe that they will equally fail at Berlin and at Budapest and at Munich and at every other place where they may be tried.

The failure at Petrograd and at Moscow was complete. The United States went away from Petrograd and from Moscow diplomatically vanquished. Colonel Robins ventures to state the fundamental reason for our discomfiture. But, before stating that reason, I must, in one respect, state him.

He is the most anti-Bolshevik person I have ever known, in way of thought; and I have known him for seventeen years. When he says now that in his judgment the economic system of Bolshevism is morally unsound and industrially unworkable, he says only what I have heard him say in every year of our acquaintance since 1902.

He was living then at a settlement in Chicago called the Chicago Commons. It had an open forum called, I think I remember, the Free Floor. On that Free Floor, and in little halls on North Clark Street, and in all sorts of other places, Robins and I heard all sorts of Bolshevik oratory in the Chicago of the early innocent twentieth century. We did not need to wait for the developments of the year 1919 in order to know that Bolshevism, after all, was not invented during the Great War by the German General Staff as a war measure. We heard Bolshevism in Chicago, all of it - the Dictatorship of the Proletariate, the Producers' Republic, the Election of Legislators by Industries, the Abolition of All Classes Except the Working-class - absolutely all of it, in the oratory of sincere and eloquent fanatics almost two decades ago. And it existed long before we heard it.

But Raymond Robins' favorite intellectual pursuit was to go after it with all the arguments he could think of. In forums and in halls and at that earnest gathering of local truth-seekers called the Friday Lunch Club he never missed an opportunity to argue against Bolshevism and against every other form of Socialism. I remember that once, when he heard from some false source that I was about to make the hideous mistake of joining the Socialist party, he kept me up till two o'clock in the morning, making me one of his best public orations, all to myself, to dissuade me. He would go to any distance out of his way in order to save any brand from the Socialist burning.

To-day, because he opposes American and Allied military intervention in Russia, certain hasty or malevolent persons try to stamp the stigma of Bolshevism on him. I only ask: how many of those persons have ever said one word against Bolshevism where to say it was dangerous? Robins spoke against Bolshevism in Petrograd itself. He labored against Bolshevism., and is publicly recorded to have labored against it, all through the period while Russia was making its choice between Kerensky and Lenin. Robins has been consistently and continuously anti-Bolshevik, in America and in Russia; but he saw the failure of our diplomacy in Russia; and he had a chance to perceive the reason, the instructive reason.

(2) Roland Chambers, The Last Englishman: The Double Life of Arthur Ransome (2009)

In the space of twenty-four hours, he had met with "eighteen or nineteen folk, ranging from the current dictator of Russia preferring to Trotsky, to our ambassador through pretty much every shade of contradictory Russian opinion". Amongst the foreign missions gathered in Petrograd, the French were taking the "maddest because the angriest view", while the Americans were the most sympathetic. On the day after the Trotsky interview, Ransome had dined with Colonel Raymond Robins, head of the American Red Cross, and Edgar Sisson, former editor of the Chicago Tribune. Robins, he concluded, was by far the superior specimen. As an evangelical Christian, an Alaskan gold prospector and straight-talking Chicago progressive, his politics were no more compatible with Bolshevism than those of Woodrow Wilson, whom he counted amongst his personal friends. But Robins had seen the Bolsheviks at work in the regional soviets. No other government, he believed, was capable of maintaining order at home while opposing German interests. If the Allies wanted an Eastern Front, they should supply the money and arms. If they wanted peace, it would have to be a general peace. By the time Ransome returned to Petrograd, Robins was on excellent terms with Trotsky and Lenin, whom he considered men of courage and integrity.

(3) William Hard, Raymond Robins' Own Story (1920)

When Robins came to Trotzky's door, there were soldiers there; and when he got inside, there was a man standing by Trotzky's desk who at once showed much excitement. "Kerensky-ite," he cried, pointing to Robins. "Counter-revolutionary." He had heard Robins addressing the Russian soldiers against peace and in favor of fighting Germany. "Counter-revolutionary," he continued.

Robins raised his arm in a gesture he hoped was commanding and calm, and said to his interpreter:

"Tell Commissioner Trotzky it is true I did everything I could to help Kerensky and to keep the Commissioner from getting into power."

Trotzky frowned.

"But tell the Commissioner," said Robins, "that I differ from some of my friends. I know a corpse when I see one, and I think the thing to do with a corpse is to bury it, not to sit up with it. I admit that the Commissioner is in power now."

Trotzky looked mollified.

"But tell the Commissioner," said Robins, "that if Kornilov or Kaledine or the Czar were sitting in his place, I would be talking to them."

Trotzky looked less mollified. Robins hastened to state his whole errand.

"Tell the Commissioner," he said, "that I have come to ask him: Can the American Red Cross Mission stay in Russia with benefit to the Russian people and without disadvantage to the Allied cause? If so, it will stay. If not, it will go."

Trotzky looked at Robins steadily, and considered. "What proof do you want?" he said.

Robins was prepared to ask a certain very definite proof. He mentioned it.

"I have thirty-two cars of Red Cross supplies," he said, "and I want to send them from here to Jassy in Rumania, consigned to the American Red Cross there. I want to change over from Kerensky guards to your guards, and I want those cars to go through to the Rumanian border under your Soviet frank. I want you to order your military people and your railway people to pass my train and to expedite it."

In making this request Robins had two purposes. He wanted to discover two things. First: Did the Soviet have the power to give protection to a train of supplies on its way across all central western Russia from Petrograd thirteen hundred miles to the River Pruth? Second: Would the Soviet be willing to move supplies away from the Petrograd district, where the Germans might get them, to Jassy, where the Germans were very unlikely to get them?...

One day, at Smolny, he turned to Robins and bluntly said:

"Colonel Robins, about this embargo on goods going from Russia into Germany, how would you like to put your officers on our frontier to enforce it?"

It was some time before Robins could gather his mind together to speak a word in reply. Then he said:

"Mr. Commissioner, I am not a diplomat or a general, and I can afford to be as ignorant as I am. I don't understand you. Your proposition sounds good, but it sounds too good. In America we would say there must be something on it. I have to ask you frankly, Why do you make it?"

Trotzky was annoyed. Besides his power of being passionate, he has a great power of being supercilious. He showed it now. His black eyes blazed out his impatience. One of his vices is intellectual pride. One of his virtues is that he confesses it. In public speaking he does not flatter an audience. He will even go to the other extreme. He will openly sneer at it. He will freeze it with contempt. A Russian journalist once described him, on such an occasion, as a freezing fire. His face then is the face of a Mephistopheles, diabolically intelligent, diabolically scornful, redeemed only by the eyes of much human suffering in a long and relentless pursuit of a human co-operative Utopia.

(4) William Hard, Raymond Robins' Own Story (1920)

Walking through the Most Holy Gate of the Kremlin, Robins reflected again on the consequences of a class Church---its consequences in the surrender of many coming rulers of working-men's parties and of working-men's governments to influences altogether outside the Church; and he arrived in the inside of the Kremlin; and he entered the building that had been the High Court Building of the Czar; and he went up three flights of stairs to a little room with velvet hangings and with a great desk of beautiful wood beautifully worked, where the Czar had been accustomed to sit and sign certain sorts of papers.

There now sits Lenin, short-built and stanch-built, gray-eyed and bald-headed and tranquil. He wears a woolen shirt and a suit of clothes bought, one would think, many years ago and last pressed shortly afterward. His room is quite still. As he has denounced "the intoxication of the revolutionary phrase," so he seems to reject the intoxication of revolutionary excitement.

He busies himself with reports and accounts of departments on his desk and receives visitors for stated lengths of time - ten minutes, five minutes, one minute. He is likely to receive them standing. He speaks to them with the low voice of the man who does not need to raise his voice.

In his ways of easy authority one may perhaps see his father, State Councilor of the Government of Simbirsk, hereditary nobleman. In his ways of thought one certainly sees his brother, executed as a political offender by the Czar's police when Lenin was seventeen.

Robins could never visit Lenin in the Czar's High Court Building without thinking of that execution and of the sanction given to it - and to all such executions - by the Russian State Church. Back of the gallows, generation after generation, in every part of Russia, stood the priests, with their vessels of gold and their vestments of lovely weavings, and with their icons, preaching obedience to autocracy and giving the word of God to back the word of the Czar, and blessing the hangman.

Out of that background came Lenin's talk. He talked with no other assumption than that religion had departed out of the public life and out of the public policy of Russia, along with the Czar. He talked of secular effort only, of only material organization.

He said to Robins: "We may be overthrown in Russia, by the backwardness of Russia or by foreign force, but the idea in the Russian revolution will break and wreck every political social control in the world. Our method of social control dominates the future. Political social control will die. The Russian revolution will kill it everywhere."

"But," said Robins, "my government is a democratic government. Do you really say that the idea in the Russian revolution will destroy the democratic idea in the government of the United States?"

"The American government," said Lenin, "is corrupt."

"That is simply not so," said Robins. "Our national government and our local governments are elected by the people, and most of the elections are honest and fair, and the men elected are the true choices of the voters. You cannot call the American government a bought government."

"Oh, Colonel Robins," said Lenin, "you do not understand. It is my fault. I ought not to have said corrupt. I do not mean that your government is corrupt in money. I mean that it is corrupt and decayed in thought. It is living in the political thinking of a bygone political age. It is living in the age of Thomas Jefferson. It is not living in the present economic age. Therefore it is lacking in intellectual integrity. How shall I make it clear to you? Well, consider this:

"Consider your states of New York and Pennsylvania. New York is the center of your banking system. Pennsylvania is the center of your steel industry. Those are two of your most important things---banking and steel. They are the base of your life. They make you what you are. Now if you really believe in your banking system, and respect it, why don't you send Mr. Morgan to your United States Senate? And if you really believe in your steel industry, in its present organization, why don't you send Mr. Schwab to the Senate? Why do you send men who know less about banking and less about steel and who protect the bankers and the steel manufacturers and pretend to be independent of them? It is inefficient. It is insincere. It refuses to admit the fact that the real control is no longer political. That is why I say that your system is lacking in integrity. That is why our system is superior. That is why it will destroy yours."

"Frankly, Mr. Commissioner," said Robins, "I don't believe it will."

"It will," said Lenin. "Do you know what ours is?"

"Not very well yet," said Robins. "You've just started."

"I'll tell you," said Lenin. "Our system will destroy yours because it will consist of a social control which recognizes the basic fact of modern life. It recognizes the fact that real power to-day is economic and that the social control of to-day must therefore be economic also. So what do we do? Who will be our representatives in our national legislature, in our national Soviet, from the district of Baku, for instance?

"This system is stronger than yours because it admits reality. It seeks out the sources of daily human work-value and, out of those sources, directly, it creates the social control of the state. Our government will be an economic social control for an economic age. It will triumph because it speaks the spirit, and releases and uses the spirit, of the age that now is.

"Therefore, Colonel Robins, we look with confidence at the future. You may destroy us in Russia. You may destroy the Russian revolution in Russia. You may overthrow me. It will make no difference. A hundred years ago the monarchies of Britain, Prussia, Austria, Russia, overthrew the government of revolutionary France. They restored a monarch, who was called a legitimate monarch, to power in Paris. But they could not stop, and they did not stop, the middle-class political revolution, the revolution of middle class democracy, which had been started at Paris by the men of the French Revolution of 1789. They could not save feudalism.

"Every system of feudal aristocratic social control in Europe was destined to be destroyed by the political democratic social control worked out by the French Revolution. Every system of political democratic social control in the world to-day is destined now to be destroyed by the economic producers' social control worked out by the Russian revolution.

"Colonel Robins, you do not believe it. I have to wait for events to convince you. You may see foreign bayonets parading across Russia. You may see the Soviets, and all the leaders of the Soviets, killed. You may see Russia dark again as it was dark before. But the lightning out of that darkness has destroyed political democracy everywhere. It has destroyed it not by physically striking it, but simply by one flash of revealment of the future."

This utter assumption of the inevitability of things was naturally appalling to Robins. It was a denial of the essence of Americanism. The essence of Americanism is an utter assumption of human free will---of human free will determining human fate by its own visions of its own moral preferences. It follows in complete Americanism that we have to consult the conscience of every citizen, irrespective of economic or other status, and that we have to proceed in the light of the accumulated consciences of the nation, as revealed roughly in majorities.

Lenin's philosophy could not convince any American like Robins. Robins came back from Russia more anti-Socialist than when he went. But he also came back knowing that Lenin's philosophy is indeed a philosophy and that it cannot be countered by pretending that it is nothing but blood and wind. It challenges Americanism with a genuine challenge. It does not merely reject the basis of Americanism. It brings forward a strongly competitive basis of its own.

Lenin, of course, frankly, was not talking about consciences or about majorities. But neither was he talking about nothing. He was talking about vitalities, economic vitalities. He was saying:

The working-class is to-day the vital economic class in Russia. Through that class we will make a Russian government better than the Czar's or Kerensky's, because it will be more vital, and better than any political government anywhere, because it will be economic. And this system, by example, will penetrate and saturate the world.

Such was Lenin in talk.

(5) William Hard, Raymond Robins' Own Story (1920)

Robins came back from Russia in June of 1918, and said that in the Soviet republic there was great strength and great capacity for resistance. Other persons, much more in the confidence of the administration at Washington, came back and said that the Soviet republic was nothing but a street corner soap-box stuffed out with a German subsidy. For month after month, then, the Allies and the anti-Bolshevik Russians attacked the Soviet republic by arms on all fronts; and the Soviet republic, blockaded, starving, sick, with no conceivable help any longer from the Kaiser and with no possible access to the imported machine-materials on which Russian industrial life had always depended, for month after month held out. Tested by life, the Soviet republic was not a feeble thing. It was a powerful thing, generating its own power out of its own power-house, somewhere, somehow.

Robins' antagonists claimed that this native internal power-house did not exist. Robins claimed that it did exist. It has been proved to exist.

So far, Robins has tried to describe certain leading characteristics of Bolshevik power and intention. He has shown the actual authority of the Soviets even in the days before the Bolsheviks controlled them; he has shown the ruinous effect of the diplomacy of Trotzky on the morale of the German Eastern army and on the morale of the proletarian element in the German population; he has shown the willingness of Trotzky and of Lenin to seek economic co-operation and to seek military co-operation with America and America's rejection of their offers; he has shown the carefully-thought-out theory of Lenin for an economic state; he has shown Lenin's willingness to concede, to compromise, in order to make some sort of state in Russia stand - stand with organization and with orderliness; and he has shown the personal and public devotion and the utter confidence which Lenin's followers give to Lenin and to Lenin's program.

Robins holds the view that no effort to combat Bolshevism can ever be successful unless it is directed against what Bolshevism is, instead of against what Bolshevism is not; and therefore he has first tried to describe what Bolshevism is, in its internal going power; and if people call him a Socialist for doing so, he can afford to be patient. Paraphrasing Lenin and rather reversing him, Robins can say to such people: "I was fighting Socialism before some of you ever thought of it, and I shall be fighting Socialism when some of you have quit."