Health Problems in 19th Century

In 1832, James P. Kay-Shuttleworth, a doctor in Manchester, carried out an investigation into the health of working-class people in the city. "In Parliament Street there is only one privy for three hundred and eighty inhabitants, which is placed in a narrow passage, whence its effluvia infest the adjacent houses, and must prove a most fertile source of disease. In this street also, cesspools with open grids have been made close to the doors of the houses, in which disgusting refuse accumulates, and whence its noxious effluvia constantly exhale. In Parliament-passage about thirty houses have been erected, merely separated by an extremely narrow passage (a yard and a half wide) from the wall and back door of other houses. These thirty houses have one privy."

Kay-Shuttleworth then went on to speculate that these conditions were the cause of a recent outbreak of cholera: "A more unhealthy spot than Allen's Court it would be difficult to discover, and the physical depression consequent on living in such a situation may be inferred from what ensued on the introduction of cholera here. A match-seller, living in the first story of one of these houses, was seized with cholera, on Sunday, July 22nd: he died on Wednesday, July 25th; and owing to the wilful negligence of his friends, and because the Board of Health had no intimation of the occurrence, he was not buried until Friday afternoon, July 27th. On that day, five other cases of cholera occurred amongst the inhabitants of the court. On the 28th, seven, and on the 29th two. The cases were nearly all fatal." (1)

Thomas Southwood Smith, a doctor working in Bethnal Green in London also argued that there was a link between sanitation and disease: " Into this part of the ditch the privies of all the houses of a street called North Street open; these privies are completely uncovered, and the soil from them is allowed to accumulate in the open ditch. Nothing can be conceived more disgusting than the appearance of this ditch for an extent of from 300 to 400 feet, and the odour of the effluvia from it is at this moment most offensive. Lamb's Fields is the fruitful source of fever to the houses which immediately surround it, and to the small streets which branch off from it. Particular houses were pointed out to me from which entire families have been swept away, and from several of the streets fever is never absent." (2)

Cholera

Cholera was one of the most fatal diseases in the 19th century. Nausea and dizziness led to violent vomiting and diarrhoea, "with stools turning to a grey liquid until nothing emerged but water and fragments of intestinal membrane... extreme muscular cramps followed, with an insatiable desire for water". It is estimated that 16,000 people died during the 1831-1832 epidemic. (3)

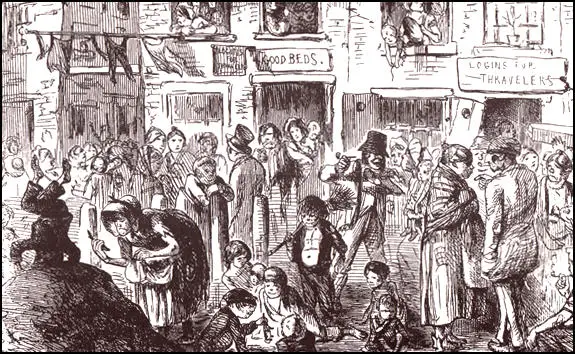

Only working-class people appeared to suffer from cholera. Stories began to circulate that doctors were spreading the disease as an excuse for getting their hands on corpses to dissect. Charles Greville, secretary to the Privy Council, noted in his diary: "The other day a Mr Pope, head of the cholera hospital in Marylebone, came to the Council Office to complain that a patient who was being removed to hospital with his own consent had been taken out of his chair by the mob and carried back, the chair broken, and the bearers and surgeon hardly escaping with their lives... In short, there is no end to the... uproar, violence, and brutal ignorance that have gone on, and this on the part of the lower orders, for whose especial benefit all the precautions are taken." (4)

Rioting broke out all over Britain. Crowds of men, women and children smashed windows at the Toxteth Park Cholera Hospital in Liverpool and pelted members of the local board of health with bricks. On 2nd September 1832, violence erupted in Manchester when a mob Swan Street Hospital, breaking down the gates and fighting a pitched battle with the police. This was as a result of a local man, John Hare, discovering that his grandson's body, who had died of cholera, had been smuggled out of the hospital by a doctor who wanted to dissect it. (5)

1835 Municipal Health Act

One of the consequences of the 1832 Reform Act was the passing of the 1835 Municipal Reform Act. This granted permission for the setting up of 178 town councils. It was also decided that all ratepayers should have a vote in council elections. These councils were also given the power to take over such matters as the town's water supply. For the first time the working-class had a vote in elections but as they had not created their own political party they rarely bothered to vote and local councils refused to take action concerning sanitation. (6)

In 1837, Parliament passed a Registration Act ordering the registration of all births, marriages and deaths that took place in Britain. Parliament also appointed William Farr to collect and publish these statistics. In his first report for the General Register Office, Farr argued that the evidence indicated that unhealthy living conditions were killing thousands of people every year. (7)

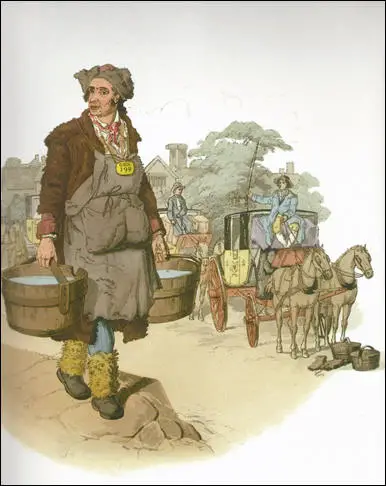

Farr argued that urban growth in the 1820s and 1830s had resulted in insanitation and poor water supplies and was probably responsible for an increase in epidemic and endemic disease. Most houses did not have pipes to take the sewerage away. Human waste was piled up in the street (called dunghills) before being taken away by people called nightmen (because by law it could only be performed after twelve o'clock at night).

A doctor reported what happened in the town of Greenock: "In Market Street is a dunghill... over twelve feet high...it contains a hundred cubic yards of impure filth, collected from all parts of town... A man who deals in dung sells it... the older the filth, the higher the price... The smell in summer is horrible... There are many houses, four stories in height, in the area... in the summer each house swarms with flies; every article of food and drink must be covered, otherwise, if left exposed for a minute, the flies immediately attack it, and it is rendered unfit for use, from the strong taste of the dunghill left by the flies." (8)

Private firms were responsible for cleaning the privies and dunghills. William Thorn worked for a firm that carried out this work and he was asked by a parliamentary committee what happened to it: "We sell it to the farmers, who use it on their land... for turnips, wheat... in fact, for all their produce". (9) Farmers in Surrey claimed that it was only liberal dressings of "London Muck" that made their heavy clays fit for cultivation. (10)

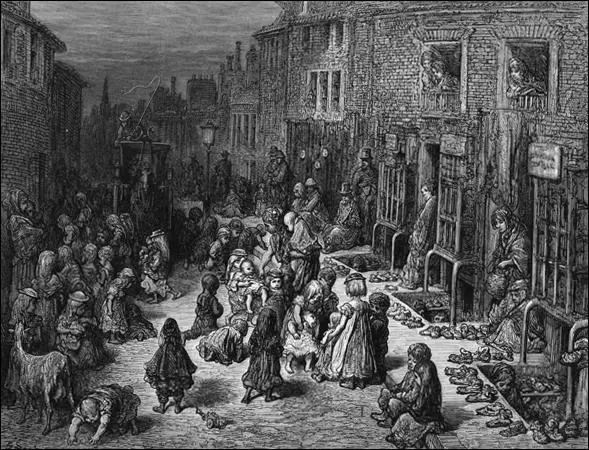

Water consumption in towns per head of population remained very low. In most towns the local river, streams or springs, provided people with water to drink. These sources were often contaminated by human waste. The bacteria of certain very lethal infectious diseases, for example, typhoid and cholera, are transmitted through water, it was not only unpleasant to taste but damaging to people's health. As Alexis de Tocqueville pointed out: "The fetid, muddy waters, stained with a thousand colours by the factories they pass, of one of the streams... wander slowly round this refuge of poverty." (11)

Henry Mayhew was a journalist who carried out an investigation into working-class living conditions: "As we passed along the reeking banks of the sewer the sun shone upon a narrow slip of the water. In the bright light it appeared the colour of strong green tea, and positively looked as solid as black marble in the shadow - indeed it was more like watery mud than muddy water; and yet we were assured this was the only water the wretched inhabitants had to drink. As we gazed in horror at it, we saw drains and sewers emptying their filthy contents into it; we saw a whole tier of doorless privies in the open road, common to men and women, built over it; we heard bucket after bucket of filth splash into it, and the limbs of the vagrant boys bathing in it seemed, by pure force of contrast, white as Parian marble. And yet, as we stood doubting the fearful statement, we saw a little child, from one of the galleries opposite, lower a tin can with a rope to fill a large bucket that stood beside her. In each of the balconies that hung over the stream the self-same tub was to be seen in which the inhabitants put the mucky liquid to stand, so that they may, after it has rested for a day or two, skim the fluid from the solid particles of filth, pollution, and disease. As the little thing dangled her tin cup as gently as possible into the stream, a bucket of night-soil was poured down from the next gallery." (12)

Poor Law Commission

In 1838 the Poor Law Commission became concerned that a high proportion of all poverty had its origins in disease and premature death. Men were unable to work as a result of long-term health problems. A significant proportion of these men died and the Poor Law Guardians were faced with the expense of maintaining the widow and the orphans. The Commission decided to ask three experienced doctors, James P. Kay-Shuttleworth, Thomas Southwood Smith and Neil Arnott, to investigate and report on the sanitary condition of some districts in London. (13)

On receiving details of the doctor's investigation, the Poor Law Commission sent a letter to the Home Secretary, Lord John Russell, suggesting that if the government spent money on improving sanitation it would reduce the cost of looking after the poor: "In general, all epidemics and all infectious diseases are attended with charges immediate and ultimate on the poor-rates. Labourers are suddenly thrown by infectious disease into a state of destitution for which immediate relief must be given: in the case of death the widow and the children are thrown as paupers on the parish. The amount of burdens thus produced is frequently so great, as to render it good economy on the part of the administrators of the poor laws to incur the charges for preventing the evils, where they are ascribable to physical causes, which there are no other means of removing." (14)

Edwin Chadwick

Debates in the House of Lords took place on this issue but it was several years before the government decided to order a full-scale enquiry into the health of British people. The person put in charge of this enquiry was Edwin Chadwick. He was a lawyer but as a member of the Unilitarian Society he had met some of the most progressive political figures in Britain, including Jeremy Bentham, James Mill, John Stuart Mill and Francis Place. (15)

Chadwick's report, The Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population, was published in 1842. He argued that slum housing, inefficient sewerage and impure water supplies in industrial towns were causing the unnecessary deaths of about 60,000 people every year: "Of the 43,000 cases of widowhood, and 112,000 cases of orphanage relieved from the poor rates in England and Wales, it appears that the greatest proportion of the deaths of heads of families occurred from... removable causes... The expense of public drainage, of supplies of water laid on in houses, and the removal of all refuse... would be a financial gain.. as it would reduce the cast of sickness and premature death." (16)

Chadwick was a disciple of Bentham who questioned the value of all institutions and customs by the test of whether they contributed to the "greatest happiness of the greatest number". (17) Chadwick claimed that middle-class people lived longer and healthier lives because they could afford to pay to have their sewage removed and to have fresh water piped into their homes. For example, he showed the average age of death for the professional class in Liverpool was 35, whereas it was only 15 for the working-classes. (18)

Chadwick criticised the private companies that removed sewage and supplied fresh water, arguing that these services should be supplied by public organisations. He pointed out that private companies were only willing to supply these services to those people who could afford them, whereas public organisations could make sure everybody received these services. He argued that the "cost of removing sewage would be reduced to a fraction by carrying it away by suspension in water". The government therefore needed to provide a "supply of piped water, and an entirely new system of sewers, using circular, glazed clay pipes of relatively small bore instead of the old, square, brick tunnels". (19)

However, there were some influential and powerful people who were opposed to Edwin Chadwick's ideas. These included the owners of private companies who in the past had made very large profits from supplying fresh water to middle-class districts in Britain's towns and cities. Opposition also came from prosperous householders who were already paying for these services and were worried that Chadwick's proposals would mean them paying higher taxes. The historian, A. L. Morton, claims that his proposed reforms made him "the most detested man in England." (20)

When the government refused to take action, Chadwick set up his own company to provide sewage disposal and fresh water to the people of Britain. He planned to introduce the "arterial-venous system". The system involved one pipe taking the sewage from the towns to the countryside where it would be sold to farmers as manure. At the same time, another pipe would take fresh water from the countryside to the large populations living in the towns.

Chadwick calculated that it would be possible for people to have their sewage taken away and receive clean piped water for less than 2d. a week. However, Chadwick launched his company during the railway boom. Most people preferred to invest their money in railway companies. Without the necessary start-up capital, Chadwick was forced to abandon his plan. (21)

John Snow

In 1849 cholera killed over 50,000 people. John Snow published On the Mode of Communication of Cholera where he argued against the theory of miasmatism (a belief that diseases are caused by noxious form of air emanating from rotting organic matter). He pointed out the disease affected the intestines not the lungs. Snow suggested the contamination of drinking water as a result of cholera evacuations seeping into wells or running into rivers. (22)

In August 1854 cholera cases began to appear in Soho. Snow investigated all 93 local deaths. He concluded the local water supply had become contaminated, for nearly all the victims used water from the Broad Street pump. At a nearby prison, conditions were far worse, but few deaths. Snow concluded that this was because it had its own well. On 7th September he requested the parish Board of Guardians to disconnect the pump. Sceptical but desperate, they agreed and the handle was removed. After this very few cases were reported. (23)

In 1855, Snow gave his views to a House of Commons Select Committee set up to investigate cholera. Snow argued that cholera was not contagious nor spread by miasmata but was water-borne. He advocated the government invested in massive improvements in drainage and sewage. It has been claimed that his research "played some part in the investment by London and other major British cities in new main drainage and sewage systems." (24)

Primary Sources

(1) Dr. James P. Kay-Shuttleworth, The Moral and Physical Condition of the Working Classes in Manchester (1832)

Near the centre of the town, a mass of buildings, inhabited by prostitutes and thieves, is intersected by narrow and loathsome streets, and close courts defiled with refuse. These nuisances exist in No. 13 District, on the western side of Deansgate, and chiefly abound in Wood Street, Spinning Field, Cumberland Street, Parliament-passage, Parliament Street, and Thomson Street. In Parliament Street there is only one privy for three hundred and eighty inhabitants, which is placed in a narrow passage, whence its effluvia infest the adjacent houses, and must prove a most fertile source of disease. In this street also, cesspools with open grids have been made close to the doors of the houses, in which disgusting refuse accumulates, and whence its noxious effluvia constantly exhale. In Parliament-passage about thirty houses have been erected, merely separated by an extremely narrow passage (a yard and a half wide) from the wall and back door of other houses. These thirty houses have one privy.

The state of the streets and houses in that part of No. 4, included between Store-street and Travis-street, and London Road, is exceedingly wretched - especially those built on some irregular and broken mounds of clay, on a steep declivity descending into Store Street. These narrow avenues are rough, irregular gullies, down which filthy streams percolate; and the inhabitants are crowded in dilapidated abodes, or obscure and damp cellars, in which it is impossible for the health to be preserved.

Unwilling to weary the patience of the reader by extending such disgusting details, it may suffice to refer generally to the wretched state of the habitations of the poor in Clay Street, and the lower portion of Pot Street; in Providence Street, and its adjoining courts; in Back Portugal Street; in Back Hart Street, and many of the courts in the neighbourhood of Portland Street, some of which are not more than a yard and a quarter wide, and contain houses, frequently three stories high, the lowest of which stories is occasionally used as a receptacle of excrementitious matter: - to many streets in the neighbourhood of Garden Street, Shudehill to Back Irk-street, and to the state of almost the whole of that mass of cottages filling the insalubrious valley through which the Irk flows, and which is denominated Irish town.

The Irk, black with the refuse of dye-works, erected on its banks, receives excrementitious matters from some sewers in this portion of the town - the drainage from the gasworks, and filth of the most pernicious character from bone-works, tanneries, size manufactories, etc. Immediately beneath Duciebridge, in a deep hollow between two high banks, it sweeps round a large cluster of some of the most wretched and dilapidated buildings of the town. The course of the river is here impeded by a weir, and a large tannery, eight stories high (three of which stories are filled with skins exposed to the atmosphere, in some stages of the processes to which they are subjected), towers close to this crazy labyrinth of pauper dwellings. This group of habitations is called "Gibraltar", and no site can well be more insalubrious than that on which it is built. Pursuing the course of the river on the other side of Ducie Bridge, other tanneries, size manufactories, and tripehouses occur. The parish burial ground occupies one side of the stream, and a series of courts of the most singular and unhealthy character the other. Access is obtained to these courts through narrow covered entries from Long Millgate, whence the explorer descends by stone stairs, and in one instance by three successive flights of steps to a level with the bed of the river. In this last mentioned (Allen's) court he discovers himself to be surrounded, on one side by a wall of rock on two others by houses three stories high, and on the fourth by the abrupt and high bank down which he descended, and by walls and houses erected on the summit. These houses were, a short time ago, chiefly inhabited by fringe, silk, and cotton weavers, and winders, and each house contained in general three or four families. An adjoining court (Barrett's) on the summit of the bank, separated from Allen's court only by a low wall, contained, besides a pig-stye - a tripe manufactory in a low cottage, which was in a state of loathsome filth. Portions of animal matter were decaying in it, and one of the inner rooms was converted into a kennel, and contained a litter of puppies. In the court, on the opposite side, is a tan yard where skins are prepared without bark in open pits, and here is also a catgut manufactory. Many of the windows of the houses in Allen's court open over the river Irk, whose stream (again impeded, at the distance of one hundred yards by a weir) separates it from another tannery, four stories high and filled with skins, exposed to the currents of air which pass through the building. On the other side of this tannery is the parish burial ground, chiefly used as a place of interment for paupers.

A more unhealthy spot than this (Allen's) court it would be difficult to discover, and the physical depression consequent on living in such a situation may be inferred from what ensued on the introduction of cholera here. A match-seller, living in the first story of one of these houses, was seized with cholera, on Sunday, July 22nd: he died on Wednesday, July 25th; and owing to the wilful negligence of his friends, and because the Board of Health had no intimation of the occurrence, he was not buried until Friday afternoon, July 27th. On that day, five other cases of cholera occurred amongst the inhabitants of the court. On the 28th, seven, and on the 29th two. The cases were nearly all fatal. Those affected with cholera were on the 28th and 29th removed to the Hospital, the dead were buried, and on the 29th the majority of the inhabitants were taken to a house of reception, and the rest, with one exception, dispersed into the town, until their houses had been thoroughly fumigated, ventilated, whitewashed, and cleansed; notwithstanding which dispersion, other cases occurred amongst those who had left the court.

(2) Dr. Thomas Southwood Smith, Account of a Personal Inspection of Bethnal Green and Whitechapel (May, 1838)

Lamb's Fields: An open area, of about 700 feet in length, and 300 feet in breadth; of this space about 300 feet are constantly covered by stagnant water, winter and summer. In the part thus submerged there is always a quantity of putrefying animal and vegetable matter, the odour of which at the present moment is most offensive. An open filthy ditch encircles this place, which at the western extremity is from 8 to 10 feet wide. Into this part of the ditch the privies of all the houses of a street called North Street open; these privies are completely uncovered, and the soil from them is allowed to accumulate in the open ditch. Nothing can be conceived more disgusting than the appearance of this ditch for an extent of from 300 to 400 feet, and the odour of the effluvia from it is at this moment most offensive.

Lamb's Fields is the fruitful source of fever to the houses which immediately surround it, and to the small streets which branch off from it. Particular houses were pointed out to me from which entire families have been swept away, and from several of the streets fever is never absent.In several houses in Collingwood-street fever of the most severe and fatal character has been raging for several months. Part of the street called Duke Street is often completely under water. This street consists of about 40 houses. In 12 of them all the members of the families residing in them have been attacked with fever, one after another, and many have died.

Hare Street Fields. An open space, close to the former, containing about 300 feet square, a large portion of which in rainy weather is completely inundated. It is surrounded on all sides but one with small houses, and several streets branch off from it. In all the houses forming the square, and in the neighbouring streets, fever is constantly breaking out, and the character of the fever in this neighbourhood has lately been very malignant.

Mape's Street. Running along the front of Mape's Street, and the back of Southampton buildings, is a large open sewer, one branch of which also passes for a considerable extent along the backs of the houses in Teal Street. The privies of the houses, placed close to the street, pour their contents into this open sewer. Part of Mape's Street consists of houses of a good description, with gardens neatly cultivated; but all of them terminate at the margin of this open and filthy sewer.

Alfred and Beckwith-rows consist of a number of buildings, each of which is divided into two houses, one back and the other front: each house is divided into two tenements, and each tenement is occupied by a different family. These habitations are surrounded by a broad open drain, in a filthy condition. Heaps of filth are accumulated in the spaces meant for gardens in front of the houses. The houses have common privies open, and in the most offensive condition. I entered several of the tenements. In one of them, on the ground floor, I found six persons occupying a very small room, two in bed, ill with fever. In the room above this were two more persons in one bed, ill with fever. In this same room a woman was carrying on the process of silk-winding.

(3) Poor Law Commission, letter to Lord John Russell, the Home Secretary (14th May, 1838)

Amongst the charges which have been unavoidably disallowed are many which increasing experience proves it necessary to submit for the sanction of the Legislature for their allowance... those charges caused by nuisances by which contagion is occasionally generated and persons reduced to destitution....

In general, all epidemics and all infectious diseases are attended with charges immediate and ultimate on the poor-rates. Labourers are suddenly thrown by infectious disease into a state of destitution for which immediate relief must be given: in the case of death the widow and the children are thrown as paupers on the parish. The amount of burthens thus produced is frequently so great, as to render it good economy on the part of the administrators of the poor laws to incur the charges for preventing the evils, where they are ascribable to physical causes, which there are no other means of removing.

(4) Edwin Chadwick, The Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population (1842)

Of the 43,000 cases of widowhood, and 112,000 cases of orphanage relieved from the poor rates in England and Wales, it appears that the greatest proportion of the deaths of heads of families occurred from... removable causes... The expense of public drainage, of supplies of water laid on in houses, and the removal of all refuse... would be a financial gain.. as it would reduce the cast of sickness and premature death....

It is proved that the present mode of retaining refuse in the house in cesspools and privies is injurious to the health and often extremely dangerous. The process of emptying them by hand labour, and removing the contents by cartage, is very offensive, and often the occasion of serious accidents.

(5) Dr. Liddle was quoted by Edwin Chadwick in his report, Interment in Towns (1843)

Nearly all the whole of the labouring population have only one room. The corpse is therefore kept in that room where the people sleep and have their meals... Bodies are almost always kept for a full week, frequently longer.., the body often occupies the only bed till they raise money to pay for the coffin.

(6) In 1842 Dr. Laurie wrote a report on the living conditions in Greenock.

In Market Street is a dunghill... over twelve feet high...it contains a hundred cubic yards of impure filth, collected from all parts of town... A man who deals in dung sells it... the older the filth, the higher the price... The smell in summer is horrible... There are many houses, four stories in height, in the area... in the summer each house swarms with flies; every article of food and drink must be covered, otherwise, if left exposed for a minute, the flies immediately attack it, and it is rendered unfit for use, from the strong taste of the dunghill left by the flies.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)