On this day on 17th April

On this day in 1521 the trial of Martin Luther begins. On 15th June 1520, Pope Leo X issued Exsurge Domine, condemning the ideas of Martin Luther as heretical and ordering the faithful to burn his books. Luther responded by burning books of canon law and papal decrees. On 3rd January 1521 Luther was excommunicated. However, most German citizens supported Luther against the Pope. The German papal legate wrote: "All Germany is in revolution. Nine tenths shout Luther as their war-cry; and the other tenth cares nothing about Luther, and cries: Death to the court of Rome!" (19)

Martin Luther was protected by Frederick III of Saxony. Pressure was placed on Emperor Charles V by the Pope to deal with Luther. Charles responded by claiming: "I am born of the most Christian emperors of the noble German nation, of the Catholic kings of Spain, the archdukes of Austria, the dukes of Burgundy, who were all to the death true sons of the Roman church, defenders of the Catholic faith, of the sacred customs, decrees and usages of its worship... Therefore I am determined to set my kingdoms and dominions, my friends, my body, my blood, my life, my soul upon the unity of the Church and the purity of the faith."

Charles V was totally opposed to the ideas of Martin Luther and it is reported that when he was presented with a copy of To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation he tore it up in a rage. However, he was in a difficult position. As Derek Wilson has pointed out: "In most of his rag-bag of territories Charles ruled by right of inheritance but in Germany he held the crown by consent of the electors, chief among whom was Frederick of Saxony."

The twenty-year old Emperor Charles invited Martin Luther to meet him in the city of Worms. On 18th April 1521, Charles asked Luther if he was willing to recant. He replied: "Unless I am proved wrong by Scriptures or by evident reason, then I am a prisoner in conscience to the Word of God. I cannot retract and I will not retract. To go against the conscience is neither safe nor right. God help me."

On this day in 1854 political activist Benjamin Tucker, the son of a whaling merchant, was born in New Bedford. He attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and while an eighteen year old student heard William Greene speak at an anarchist meeting in Boston. He was immediately converted to the cause and the two men became close friends.

In 1872 he started a sexual relationship with Victoria Woodhull, sixteen years his senior and advocate of free love. Later that year she was nominated as the presidential candidate of the Equal Rights Party. Although laws prohibited women from voting, there was nothing stopping women from running for office. Woodhull suggested that Frederick Douglass should become her running partner but he declined the offer.

During the campaign Victoria Woodhull called for the "reform of political and social abuses; the emancipation of labor, and the enfranchisement of women". Woodhull also argued in favour of improved civil rights and the abolition of capital punishment. These policies gained her the support of socialists, trade unionists and women suffragists. However, conservative leaders of the American Woman Suffrage Association, such as Susan Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, were shocked by some of her more extreme ideas and supported Horace Greeley in the election.

Friends of President Ulysses Grant decided to attack Woodhull's character and she was accused of having affairs with married men. It was also alleged that Victoria's previous husband was an alcoholic and her sister, Utica Claflin, took drugs. Woodhull became convinced that Henry Ward Beecher was behind these stories and decided to fight back. She now published a story in the Woodhull and Claflin's Weekly that Beecher was having an affair with a married woman.

Woodhull was arrested and charged under the Comstock Act for sending obscene literature through the mail and was in prison on election day. (Woodhull's name did not appear on the ballot because she was one year short of the Constitutionally mandated age of thirty-five.) Over the next seven months Woodhull was arrested eight times and had to endure several trials for obscenity and libel. She was eventually acquitted of all charges but the legal bills forced her into bankruptcy. Tucker's relationship with Woodhull ended in 1875.

William Greene introduced Tucker to Ezra Heywood and Josiah Warren. All three men were supporters of Mikhail Bakunin who at that time was living in Switzerland. Tucker became a convert and wrote: "We are willing to hazard the judgment that coming history will yet place him (Bakunin) in the very front ranks of the world's great social saviours. The grand head and face speak for themselves regarding the immense energy, lofty character, and innate nobility of the man. We should have esteemed it among the chief honors of our life to have known him personally, and should account it a great piece of good fortune to talk with one who was personally intimate with him and the essence and full meaning of his thought and aspiration."

Benjamin Tucker spoke several languages and was an accomplished translator. After reading the work of Pierre Joseph Proudhon he published the first English edition of What is Property. Over the next few years he translated the work of Mikhail Bakunin, Peter Kropotkin, Victor Hugo, Nikolai Chernyshevsky and Leo Tolstoy.

Tucker worked for the radical journals The Word and the Radical Review before founding the anarchist journal, Liberty in 1881. In the first edition Tucker praised Sophie Perovskaya, the Russian revolutionary who had just been executed for taking part in the assassination of Tsar Alexander II. He was also the author of State Socialism and Anarchism (1899).

Paul Avrich has argued: " It (Liberty) was meticulously designed and edited, with brilliant galaxy of contributors, not least among them Tucker himself. Its debut in 1881 was a milestone in the history of the anarchist movement, and it won an audience wherever English was read. As a publisher, moreover, Tucker issued a steady stream of books and pamphlets on anarchism and related subjects over a period of nearly thirty years."

After his mother died she left Tucker a large sum of money. He put it in an annuity and had a comfortable income of $1,650 a year. In 1906 he opened Tucker's Unique Book Shop in New York City. He employed Pearl Johnson and although she was 25 years younger than Tucker, they began an affair. She was pregnant with his child when the shop suffered a fire, destroying all his books, papers and printing equipment. Soon after his daughter, Oriole, was born, the family moved to France.

Tucker and his family lived in Le Vésinet. According to his daughter, Oriole Tucker: "My parents... were never legally married. Yet they were the most monogamistic couple I ever saw, absolutely devoted to each other until the end." During the First World War the family moved to Nice. He remained an anarchist but did not have contact with Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman who also lived on the Riviera. Goldman later commented: "I would not go around the corner to meet him. He was an old fogey before he grew old." Benjamin Tucker died in Monaco on 22nd June, 1939.

On this day in 1886 Beatrice Potter attends her first meeting of the Board of Statistical Research run by Charles Booth, who was involved in studying the lives of working people living in London: "Charles Booth's first meeting of the Board of Statistical Research at his London office. Object of the Committee is to get a fair picture of the whole of London society - the 4,000,000 - by district and employment, the two methods to be based on census returns. At present Charles Booth is the sole worker in this gigantic undertaking. I intend to do a little bit of it while I am in London, not only to keep the Society alive, but to keep me in touch with actual facts so as to limit my study of the past to that part of it useful in the understanding of the present."

Beatrice was assigned to study and investigate the lives of the dock workers in the East End. Other topics covered by Beatrice included Jewish immigration and sweated labour in the tailoring trade. Her articles on dock workers and the sweating trades were published in the journal, the Nineteenth Century and as a result was invited to testify before the House of Lords on the subject.

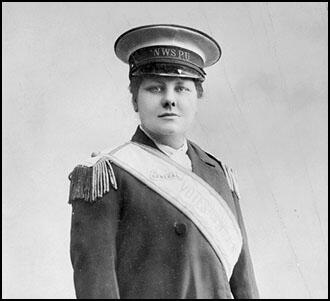

On this day in 1913 The Daily Herald reports that Flora Drummond has gone on hunger-strike. "She (Flora Drummond) did not like the idea of hunger striking any more than the most normal human beings, but hunger strike she would if she were sent to gaol. She had experience of short commons while engaged on sociology work in the East End."

In May 1914, she was arrested again. For the ninth time she was imprisoned. After going on hunger strike she was released under the Cat and Mouse Act. Drummond recuperated in the Isle of Arran but she returned to Clement's Inn after the outbreak of the First World War. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

On this day in 1914 Christabel Pankhurst suggested the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) should stop working with the Labour Party. Christabel had now decided that the WSPU should not form any alliance with male politicians. Christabel wrote in The Suffragette: "For Suffragists to put their faith in any men's party, whatever it may call itself, is recklessly to disregard the lessons of the past forty years… The truth is that women must work out their own salvation. Men will not do it for them".

Sylvia Pankhurst was criticised for speaking on the same platform as the Labour MP, George Lansbury. Christabel told her: "You have your own ideas. We do not want that; we want all our women to take their instructions and walk in step like an army!" Sylvia later recalled: "Too tired, too ill to argue, I made no reply. I was oppressed by a sense of tragedy, grieved by her ruthlessness. Her glorification of autocracy seemed to me remote from the struggle we were waging."

Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Labour Party, had argued for many years that women's suffrage was a necessary part of a socialist programme. However, MacDonald rejected the WSPU use of violence: "I have no objection to revolution, if it is necessary but I have the very strongest objection to childishness masquerading as revolution, and all that one can say of these window-breaking expeditions is that they are simply silly and provocative. I wish the working women of the country who really care for the vote ... would come to London and tell these pettifogging middle-class damsels who are going out with little hammers in their muffs that if they do not go home they will get their heads broken."

On this day in 1943 Chief Inspector Percy Datlen of Dover CID, complains about the behaviour of local people after bombing raids: "In cases where there are several houses bombed out in one street, the looters have systematically gone through the lot. Carpets have been stripped from the floors, stair carpets have been removed: they have even taken away heavy mangles, bedsteads and complete suites of furniture. We believe it is the greatest organized looting that has yet taken place and many front line citizens who have returned to their homes to carry on their essential jobs there are facing severe financial difficulties as a result of the work of the gang."

One of the most shocking crimes committed during wartime was the looting from bombed houses. In the first eight weeks of the London Blitz a total of 390 cases of looting was reported to the police. On 9th November, 1940, the first people tried for looting took place at the Old Bailey. Of these twenty cases, ten involved members of the Auxiliary Fire Service.

The Lord Mayor of London suggested that notices should be posted throughout the city, reminding the population that looting was punishable by hanging or shooting. However, the courts continued to treat this crime leniently. When a gang of army deserters were convicted of looting in Kent the judge handed down sentences ranging from five years' penal servitude to eight years' hard labour. Some critics pointed out that Nazi Germany suffered less from this crime as looters were routinely executed for this offence.

In Leeds a judge announced that "more than two whole days have been occupied in dealing with cases of looting which have occurred in one city (Sheffield)... In many cases these looters have operated on a wholesale scale. There were actually two-men who had abandoned well-paid positions, one of them earning £7 to £9 a week, and work of public importance, and who abandoned it to take up the obviously more remunerative occupation of looting."

On this day in 1961 a group of Cuban exiles financed and trained by the CIA lands at the Bay of Pigs in Cuba. On 3rd April, 1961, President John F. Kennedy met secretly with a dozen of his top advisers. He also brought with him Senator William Fulbright, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Fulbright made a moral argument against the United States sponsoring secret invasions of other countries. His contribution upset others in the room. Some, like Paul Nitze, the assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs, found themselves voting for the invasion, not because they really believed in it, but because they disliked Fulbright's arguments. Adolf Berle, the State Department specialist on Latin America, cried out, "I say, let 'er rip!"

Richard Bissell, Deputy Director for Plans was encouraged by the meeting. He felt he had finally been given approval, although Kennedy reserved the right to make a final decision on the eve of the invasion. However, Bissell was worried by Kennedy's attitude towards the invasion. "Without anyone's realizing it, however, there was something of an undercurrent in the government that was serving to undermine what chances the operation had... On at least two occasions (reported to me by eyewitnesses), some of the Joint Chiefs said they felt the CIA was exaggerating the need for air cover for the landing... I was shocked. We all knew only too well that without air support the project would fail."

Kennedy told Bissell that it was vitally important that the United States government could not be connected to the invasion of Cuba. Bissell tried to change his approach by approaching the president's brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. Bissell said that without air cover the odds of success as only two out of three. Soon afterwards, the New York Times reported that the United States was training Cuban exiles for an imminent invasion. Kennedy feared that the CIA was leaking information to the press. He told his press secretary, Pierre Salinger: "I can't believe what I'm reading! Castro doesn't need agents over here. All he has to do is read our papers."

David Atlee Phillips and Tracy Barnes developed an elaborate cover story to give the impression that the air strikes on Cuba would to be an inside job - originating from Cuba, not from the CIA's secret air base in Nicaragua. After the raid a pair of B-26s would land in Florida, piloted by Cubans claiming to be defectors. They would tell newsmen that they had bombed and shot up their own airfields on the flight to freedom. On Saturday morning, 15th April, 1961, eight B-26s out of Nicaragua, manned by Cuban pilots, bombed three of Castro's airfields. After the air raids Cuba was left with only eight planes and seven pilots.

Later that day Raúl Roa García, the Cuban foreign minister, demanded the floor of the United Nations General Assembly to declare that his country had been bombed by U.S. aircraft. Adlai Stevenson, the U.S. representative, held up a photograph of one of the planes that had landed in Florida. "It has the markings of Castro's air force on the tail, which everyone can see for himself. The Cuban star and the initials F.A.R., Fuerza Aerea Revolucionaria, are clearly visible." Phillips watched the speech on television and commented "what a smooth phony he is". Then it occurred to him that Stevenson didn't know the truth and had not been full briefed by Tracy Barnes about the operation.

The cover story began to peel away almost immediately. As Terence Cannon pointed out: "Nine CIA planes had taken off that morning from Puerto Cabezas (Nicaragua): eight for Cuba and one directly to Miami... each plane bore an imitation of the Cuban Air Force insignia. The single pilot bound for Miami was to arrive there just after the others had bombed Cuba... An enterprising reporter got close enough to his plane to notice that dust and grease covered the bomb-bay doors and that the muzzles of the guns were taped shut. The plane had obviously not participated in any attack."

Stevenson was furious as he felt that he had been "deliberately tricked" by his own government and sent a cable to Dean Rusk, the Secretary of State: "I had definite impression from Tracy Barnes when he was here that no action would be taken which could give us political difficulty during current U.N. debate.... I do not understand how we could let such an attack take place two days before debate on Cuban issue in the General Assembly. Nor can I understand, if we could not prevent such an outside attack from taking place at the time, why I could not have been warned."

On 17th April, five merchant ships carrying 1,400 Cuban exiles headed for the Bay of Pigs. The director of the CIA, Allen W. Dulles was in Puerto Rico during the invasion. He left Charles Cabell in charge. Instead of ordering the second air raid he checked with Dean Rusk. He contacted Kennedy who said he did not remember being told about the second raid. After discussing it with Rusk he decided to cancel it. Instead the operation tried to rely on Radio Swan, broadcasts being made on a small island in the Caribbean by David Atlee Phillips, calling for the Cuban Army to revolt. They failed to do this. Instead they called out the militia to defend the fatherland from "American mercenaries”.

At 6:30 a.m. one of the Brigade 2506's landing ships, the Houston, was hit at the waterline by a rocket fired from Cuba. The ship quickly began to sink. At 9:30 a.m. a second ship of the invasion force, the Rio Escondo, went up in a giant fireball. Castro's planes had hit 200 hundred barrels of aviation fuel. A communications van sank with the ship, cutting off any air-land radio contact. Castro also deployed columns of soldiers and tanks to resist the invasion. By Monday afternoon, the battle had clearly turned against the Brigade.

Richard Bissell later wrote: "The president's decision to cancel the D day air strikes, the limited availability of aircraft and crews, and an air arm forbidden by the president to engage in strategic bombing meant that some of Castro's air force survived and sank two supply ships. This was a turning point for the brigade since the remainder of the supply ships withdrew to a position some fifty miles offshore, where they were presumably out of range of further attack but unavailable to give logistical support. Without resupply and air cover, the venture was doomed."

Richard Helms, who was to replace Bissell as Deputy Director of Central Intelligence for Plans, also blamed President Kennedy for the Bay of Pigs disaster. "The ZAPATA Brigade force seized a beachhead along the Bay of Pigs - the original and more feasible landing area having been vetoed by President Kennedy. Two days and some hours later, the surviving 1189 members of the attack force were still contained within the beachhead. After President Kennedy refused to provide the desperately needed additional air support and their ammunition was almost exhausted, the men had no choice but to surrender."

Ted Shackley, another senior figure in the CIA involved in the operation, pointed out: "Covert action is not a weapon that intelligence services can wield at will. Spymasters may be called upon to help kings and field marshals with their intrigues, but the latter call the shots. And a corollary to this is that no covert-action operation mounted by an intelligence service has much chance of success if it is not solidly supported at the highest levels of government and coordinated with the leadership's other means of persuasion - diplomatic, military and propagandistic."

On 20th April, 1961, Bissell told President Kennedy that the Brigade was trapped on the beaches and encircled by Castro's forces. Bissell asked for United States air support but Kennedy replied that he still wanted "minimum visibility". At 2:32 on Wednesday afternoon Pepe San Román, the Brigade's commander, reported that Castro's tanks were breaking through. His last message was "Am destroying all equipment and communications. I have nothing left to fight with. Am taking to the swamps. I can't wait for you." To his CIA handler, safely aboard ship, he had a last farewell: "And you, sir," he said, "are a son of a bitch."

President Kennedy had presided at all the discussions, and from the moment the Joint Chiefs of Staff gave the operation their approval, he had given it his full presidential backing. On 21st April, Kennedy admitted blame for the failed Bay of Pigs invasion: "There's an old saying that victory has a hundred fathers and defeat is an orphan ... Further statements, detailed discussions, are not to conceal responsibility because I'm the responsible officer of the Government."

An estimated 67 Cuban exiles from Brigade 2506 were killed in action. Aircrews killed totaled 6 from the Cuban air force, 10 Cuban exiles and 4 American airmen. This included Thomas Ray, a CIA officer. The final toll in Cuban armed forces during the conflict was 176 killed in action. This figure includes only the Cuban Army and it is estimated that about 2,000 militiamen were killed or wounded during the fighting. The airfield attacks on 15 April left 7 Cubans dead and 53 wounded.

The Cuban government carried out a detailed investigation into the 1,197 captured troops. It was claimed they were composed of: 100 plantation owners, 67 landlords of apartment houses, 24 large property owners, 112 businessmen, 194 ex-soldiers of Batista (including 14 wanted for murder and torture during the revolutionary war), 179 "idle rich" and 35 industrial magnates. Together they owned 923,000 acres of land, 9,666 houses and apartment buildings, 70 factories, 10 sugar mills, 3 banks, 5 mines and 12 nightclubs.

However, behind the scenes, it was decided that the director of the CIA, Allen W. Dulles, should take most of the blame for the failed operation. President Kennedy suggested Dulles should resign. He refused claimed that Robert Kennedy was the one to go as he had been the main figure calling on Castro to be removed. Eventually it was agreed that Dulles should stay on for a few months and that his resignation would not seem like a sacking for his role in the Bay of Pigs disaster. John McCone replaced him on 29th November, 1961.