On this day on 15th June

On this day in 1381 Wat Tyler is killed. It was agreed that another meeting should take place between Richard II and the leaders of the rebels at Smithfield on 15th June, 1381. William Walworth rode "over to the rebels and summoned Wat Tyler to meet the king, and mounted on a little pony, accompanied by only one attendant bearing the rebel banner, he obeyed". When he joined the king he put forward another list of demands that included: the removal of the lordship system, the distribution of the wealth of the church to the poor, a reduction in the number of bishops, and a guarantee that in future there would be no more villeins.

Richard II said he would do what he could. Wat Tyler was not satisfied by this reply. He called for a drink of water to rinse out his mouth. This was seen as extremely rude behaviour, especially as Tyler had not removed his hood when talking to the king. One of Richard's party shouted out that Tyler was "the greatest thief and robber in Kent". The author of the Anonimalle Chronicle of St Mary's claims: "For these words Wat wanted to strike the valet with his dagger, and would have killed him in the king's presence; but because he tried to do so, the Mayor of London, William of Walworth... arrested him... Wat stabbed the mayor with his dagger in the body in great anger. But, as it pleased God, the mayor was wearing armour and took no harm.. he struck back at the said Wat, giving him a deep cut in the neck, and then a great blow on the head. And during the scuffle a valet of the king's household drew his sword, and ran Wat two or three times through the body... Wat was carried by a group of the commons to the hospital for the poor near St Bartholomew's, and put to bed. The mayor went there and found him, and had him carried out to the middle of Smithfield, in the presence of his companions, and had him beheaded."

The peasants raised their weapons and for a moment it looked as though there was going to be fighting between the king's soldiers and the peasants. However, Richard rode over to them and said: "Will you shoot your king? I will be your chief and captain, you shall have from me that which you seek " He then spoke to them for some time and eventually they agreed to go back to their villages.

The death of Wat Tyler from Jean Froissart, Chronicles (c. 1470)

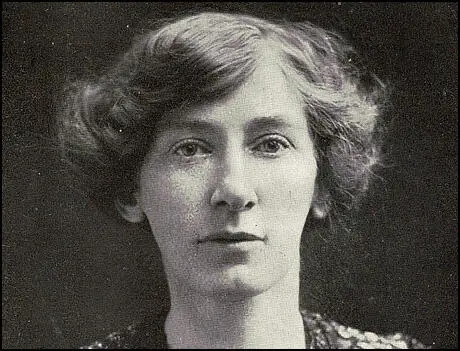

On this day in 1872 Cicely Mary Hamilton, the daughter of Danzil Hammill and Maude Piers, was born in Paddington . At the time of the birth, Hammill was a captain in the Gordon Highlanders. When Cicely was ten years old, her mother disappeared from her life. Although Cicely always refused to talk about the matter, it is believed her mother was committed to an asylum. With Hammill serving in Egypt, Cicely was brought up by foster parents.

After an education at a boarding school in Malvern, Cicely became a pupil-teacher. She disliked the work and soon found employment as an actress with a touring company. It was during this time she changed her name from Hammill to Hamilton. In 1897 Hamilton joined a Shakespearian company led by the American actor, Edmund Tearle. Over the next few years she appeared as Gertrude in Hamlet, Emilia in Othello and one of the witches in Macbeth.

Unable to obtain leading roles on the London stage, Hamilton decided to turn to writing. Her first play, The Traveller Returns, was performed at the Pier Theatre, Brighton, in May 1906. This was followed by Diana of Dobsons. The play was an immediate success and ran at the Kingsway, London, for 143 performances.

In 1908 Hamilton joined the Women's Social and Political Union. However, Hamilton disliked the autocratic way that Emmeline Pankhurst ran the organisation and after a few months left to join the Women's Freedom League. She was also a founder member of the Actresses' Franchise League and the Women Writers Suffrage League. Hamilton wrote two propaganda plays, How the Vote was Won (1909) and A Pageant of Great Women. She also joined with the composer, Ethel Smythe, to write March of the Women.

Hamilton's most important contribution to the feminist movement was the influential, Marriage as a Trade (1909). In the book Hamilton argued that woman were brought up to look for success only in the marriage market and this severely damaged their intellectual development. She followed this with the novel, Just to Get Married (1911) that explores the degrading scheming of the heroine to ensnare a husband.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Elsie Inglis, one of the founders of the Scottish Women's Suffrage Federation, suggested that women's medical units should be allowed to serve on the Western Front. With the financial support of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), Inglis formed the Scottish Women's Hospitals Committee. Hamilton was one of the first women to join the organisation and in November 1914 helped to establish the 200 bed Auxiliary Hospital at Royaumont Abbey in France.

In the summer of 1916 Hamilton helped nurse soldiers wounded at the Battle of the Somme. This included treating 300 new patients in three days. Others who worked with her at Royaumont Abbey included Elsie Inglis, Louisa Martindale, Evelina Haverfield and Ishobel Ross.

In May 1917 Hamilton left the Scottish Women's Hospital Unit and joined the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps. After training in England, Hamilton returned to France where she took control of a postal unit. However, soon afterwards, she was asked to form a repertory company at the Somme. For the rest of the war Hamilton's company performed a series of plays for Allied soldiers fighting on the Western Front.

Hamilton's experience of the First World War had a profound impact on her view of international politics. She wrote in Senlis (1917): "Modern warfare is so monstrous, all-engrossing and complex, that there is a sense, and a very real sense, in which hardly a civilian stands outside it; where the strife is to the death with an equal opponent the non-combatant ceases to exist. No modern nation could fight for its life with its men in uniform only; it must mobilize, nominally or not, every class of its population for a struggle too great and too deadly for the combatant to carry alone."

After the war Hamilton became a freelance journalist working for newspapers such as the Daily Mail, the Daily Mirror and the Daily Express. She was also a regular contributor to the feminist journal, Time and Tide where she campaigned for free birth control advice for women and the legalization of abortion.

Hamilton's autobiography Life Errant, was published in 1935. In it she wrote: "If and when our civilization comes to its ruin, the destructive agent will be Science; man's knowledge of Science, applied to warfare, meaning slaughter not only of human bodies, but of human institutions, of all we have created through the centuries."

Other books written by Hamilton include Modern Italy (1932), Modern France (1933), Modern Russia (1934), Modern England (1938), Lament for Democracy (1940) and The Englishwoman (1940).

Cicely Mary Hamilton died on 6th December, 1952.

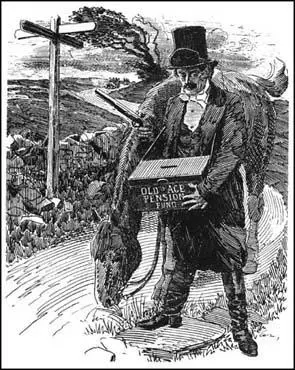

On this day in 1908 David Lloyd George makes speech on Old Age Pensions. "You have never had a scheme of this kind tried in a great country like ours, with its thronging millions, with its rooted complexities... This is, therefore, a great experiment... We do not say that it deals with all the problem of unmerited destitution in this country. We do not even contend that it deals with the worst part of that problem. It might be held that many an old man dependent on the charity of the parish was better off than many a young man, broken down in health, or who cannot find a market for his labour."

On this day in 1915 General John French sends a dispatch about the impact of poison gas attacks.

All the scientific resources of Germany have apparently been brought into play to produce a gas of so virulent and poisonous a nature that any human being brought into contact with it is first paralysed and then meets with a lingering and agonising death.

Following a heavy bombardment, the enemy attacked the French Division at about 5 p.m., using asphyxiating gases for the first time. Aircraft reported that at about 5 p.m. thick yellow smoke had been seen issuing from the German trenches between Langemarck and Bixschoote. The French reported that two simultaneous attacks had been made east of the Ypres-Staden Railway, in which these asphyxiating gases had been employed.

What follows almost defies description. The effect of these poisonous gases was so virulent as to render the whole of the line held by the French Division mentioned above practically incapable of any action at all. It was at first impossible for anyone to realise what had actually happened. The smoke and fumes hid everything from sight, and hundreds of men were thrown into a comatose or dying condition, and within an hour the whole position had to be abandoned, together with about 50 guns.

On this day 1943 the world's first jet bomber makes its first flight. Throughout the Second World War both the Royal Air Force and the Luftwaffe attempted to produce an effective jet aeroplane. The fighter Messerschmitt Me 262 made its first test flight on 25th March, 1942. The following year, the jet bomber, the Arado Ar 234B appeared and made its first flight on 15th June, 1943.

The world's first jet bomber had a maximum speed of 461 mph (742 km) and had a range of 1,103 miles (1,775 km). It was 41 ft 5 in (12.63 m) long with a wingspan of 46 ft 3 in (14.10 m). The aircraft was armed with two 20 mm cannons and could carry 3,300 lb (1,500 kg) of bombs.

The Arado AR 234B arrived too late to make an impact on the course of the war. Around two hundred were built and only 38 of them saw action before the end of the Second World War.