1923 Cup Final

West Ham United was elected to the Second Division of the Football League after the First World War. The club decided to increase the admission price to 1 shilling (5p). Over 20,000 turned up to Upton Park to see the first league game against Lincoln City on 30 August 1919. The game ended up in a 1-1 draw.

The club finished in 7th place in the Second Division in the 1919-1920 season. The following season the club finished in 5th place. George Kay, the captain of West Ham, had been purchased from Bolton Wanderers for a fee of £100. A small group of young local players such as Syd Puddefoot, Jack Tresadern, Edward Hufton, Sid Bishop and Jimmy Ruffell had also arrived in the first-team.

Syd King, the manager of West Ham United also made some shrewd signings for small fees. This included Vic Watson from Wellingborough Town (£25), Billy Brown from Hetton (£25) and Jack Young from South Shields (£300).

The star of the side was Syd Puddefoot who had scored 107 goals in 194 games for the club. The team relied heavily on Puddefoot's goals and it was great shock to the fans when Syd King sold him to Falkirk for the British record fee of £5,000 in February 1925.

As the authors of the The Essential History of West Ham United (2000) pointed out that his departure "nearly caused a riot among Hammers fans". However, the club blamed Puddefoot in a statement issued after his transfer: "The departure of Syd Puddefoot came as no surprise to those intimately connected with him. It is an old saying that everyone has one chance in life to improve themselves and Syd Puddefoot is doing the right thing for himself in studying his future. We understand that he will be branching out in commercial circles in Falkirk and when his football days are over he will be assured of a nice little competency."

The truth of the matter was that Syd Puddefoot was very reluctant to move to Scotland to play for Falkirk. However, at this time footballers had little control over these matters. At the time of his departure, it looked like West Ham United would win promotion to the First Division. However, without their top goalscorer, the club lost five of their last seven games and finished in 4th place at the end of the 1921-22 season.

However, Syd King used the money wisely and purchased three talented players: Billy Henderson from Aberdare Athletic (£650), Dick Richards from Wolves (£300) and Billy Moore from Sunderland (£300). He was also convinced that the young Vic Watson would be even better than the departed Syd Puddefoot.

According to Jimmy Ruffell, it was trainer Charlie Paynter who decided on the team's tactics: "Syd King was a good manager. But he left a lot of the day-to-day stuff to our trainer Charlie Paynter. It was Charlie that most of us talked to about anything. Syd King was more about doing deals to get players to play for West Ham."

Syd King (manager), Billy Henderson, Sid Bishop, George Kay, Edward Hufton, Jack Young, Jack Tresadern, Charlie Paynter (trainer). Front row: Dick Richards, Billy Brown, Vic Watson, Billy Moore, Jimmy Ruffell.

The new line-up took a while to settle down at the start to the 1921-22 season, winning only three of their first fourteen games. This put them in 18th place and it looked like that the club had no chance of getting promotion that year.

The turning point came with a 1-0 victory over Clapton Orient on 18th November, 1921. West Ham won nine of their next eleven games. The forward line of Jimmy Ruffell, Billy Moore, Vic Watson, Billy Brown and Dick Richards began to click. As Ruffell pointed out: "West Ham were a good passing team. Most of the time you had an idea where men were or men would make themselves ready to get the ball from another player. I think we were one of the few clubs to really practice that. Then, with their good forward line, Vic Watson, Bill Moore and I was okay too, West Ham always had a chance at getting a goal."

West Ham United also beat Hull City 3-2 in the 1st Round of the FA Cup on 13th January, 1923. They faced Brighton & Hove Albion in the 2nd round. After a 1-1 draw they beat them 1-0 in the replay. This was followed by a 2-0 victory over Plymouth Argyle. However, they took three games before the eventually beat Southampton 1-0 on 19th March, to reach the semi-final for the first time in their history.

West Ham was also in good form in the league going on a 10 match unbeaten run since the start of the new year. This included a 6-0 victory on 15th February away from home against Leicester City, one of their main rivals for the championship. Notts County and Manchester United were also doing well that season so it appeared that four clubs were fighting for the two promotion places.

On 24th March, 1923, West Ham played Derby County in the semi-final of the FA Cup at Stamford Bridge in front of a 50,000 crowd. Derby, who had not lost a goal so far in the competition was expected to win the game. George Kerr, a 17-year-old supporter who lived in Boleyn Road, was one of those who watched the game. "For the first few minutes the ball hardly left the Hammers' half. Then Hufton took a goal-kick straight down the middle. Watson trapped the ball then swung around hitting it out to the left about 10 yards ahead of Ruffell who took it in his stride and carried it about another 20 yards before he swung over a slightly lofted centre which Brown volleyed into the top left-hand corner of the net."

The goal by Billy Brown was followed by another one from Billy Moore. After ten minutes West Ham had a two goal lead. Further goals by Brown, Moore and Jimmy Ruffell gave the Hammers an easy 5-2 victory. The Stratford Express reported: "On Saturday we saw a team working together like a well-oiled machine, full of vitality in attack, confident in its methods, accurate in its execution and driving home its advantages to the full. The Derby defence was continually harassed by a forward line which would have tested the best defence in the country. There was method and precision in everything it did, and its deadly accuracy was confirmed by the fact on five occasions it beat a defence which in the previous four rounds had not given away a goal."

The Daily Mail argued that: "West Ham have never played finer football. It was intelligent, it was clever, and it was dashing. They were quick, they dribbled and swerved, and passed and ran as if the ball was to them a thing of life and obedient to their wishes. They were the master tacticians, and it was by their tactics that they gained... Every man always seemed to be in his place, and the manner in which the ball was flashed from player to player - often without the man who parted from it taking the trouble to look - but with the assistance that his colleague was where he ought to be - suggested the well-assembled parts of a machine, all of which were in perfect working order."

The prospect of playing their first FA Cup Final did not damage their league form. A week later West Ham United beat Crystal Palace 5-1 with Vic Watson scoring four of the goals. They followed this with a 5-2 win over Bury. There were also wins against Hull City (3-0) and Fulham (2-0). However, with the title in their grasp, pre-cup nerves set in and the club lost games against Barnsley and Notts County in the weeks preceding the final that was to be the first to be held at the Empire Stadium at Wembley.

The new stadium had just been built by Robert McAlpine for the British Empire Exhibition of 1923. It was originally intended to be demolished at the end of the Exhibition. However, it was later decided to keep the building to host football matches. The first match was to be the 1923 Cup Final and it was only completed four days before the game was due to take place.

Bolton Wanderers was a First Division side and was strong favourites to win the game. The team included players such as Joe Smith, Billy Jennings, Jimmy Seddon, John Reid Smith, David Jack, Billy Butler, Walter Rowley, Ted Vizard, Harry Nuttall, Dick Pym, Alex Finney and Bob Haworth.

As Brian Belton pointed out in The Lads of 1923 (2006): "Syd King had become the focus of an unprecedented level of media exposure during the build up for the Cup final as journalists grew ever more preoccupied with the Hammers' bargain priced team. The eleven selected to contest the biggest match in the club's history had cost a mere £2,025. So by 1923, what would become West Ham's reputation for succeeding without spending was already well established. But even by the Hammers' standards, the line-up for the Cup final that year was something of a bargain eleven. Only six of the players on show had cost more than £50. The sale of Puddefoot for £5,000 the previous season puts this in perspective. In contrast, Bolton, whilst not an expensive side to put together, were a team with pedigree, worth at least as much as any side in the world."

To Syd King, promotion to the First Division was the most important objective and he consistently played his strongest team in the league, giving no one a rest. As a result, West Ham also had injury problems and Jimmy Ruffell, Edward Hufton, Vic Watson and Jack Young all faced fitness tests on the morning of the final.

The Empire Stadium had a capacity of 125,000 and so the Football Association did not consider making it an all-ticket match. After all, both teams only had an average attendance of around 20,000 for league games. However, it was rare for a club from London to make the final of the FA Cup and supporters of other clubs in the city saw it as a North v South game.

Jimmy Ruffell commented that getting to the FA Cup Final was very important to the people living in the area: "It seemed like the most wonderful thing anyone had done as far as anything to do with West Ham was concerned... It was a hard time for most people around the East End. That was the best thing about it really; giving people, kids, something to smile about." It has to be remembered that in the 1920s an average of 150 Britons died every day as a consequence of malnutrition. A significant percentage of these people lived in the East End of London.

George Kerr, who provided such a vivid description of the semi-final victory over Derby County, was also determined to see the final. "I booked my seat on a London General Omnibus... It was scheduled to leave Barking at 11 a.m. but actually left at 11.30 a.m. But who cared? With a 3 p.m. kick-off there was no worry, or so we thought... When we were about two or three miles away from the stadium we suffered a shock. We were told by some coming away from the stadium that it was no good going on because the gates were closed, but we pressed on. The buses finally stopped about three-quarters of a mile away from the stadium which was about as close as they could get." Kerr refused to be beaten and decided to finish the journey by foot.

Jim Belton, who was a passionate West Ham fan, found the the sight of Wembley Stadium awe inspiring: "It was such a size! From the outside it was like a great big castle. For us it was one of the wonders of the world. People were standing still about a mile from Wembley and just staring at it. Some groups were lost for words."

William Godbold, the Mayor of West Ham, arrived early for the game but still had trouble getting to his seat: "The whole thing was a muddle. That was to be observed at the very outset, because there were not police outside the turnstiles. The police were inside and I have it officially that only 200 police had been employed to deal with the crowd."

The Bolton Evening News reported: "It is computed that fully 250,000 people made their way to the imposing and spacious ground form all parts of the Empire, all anxious to see the blue riband of the football world decided. About 60,000 people had passed inside the turnstiles when pandemonium broke loose. One of the main exits was broken down and thousands of people surged inside the enclosure, and from that moment the situation showed signs of getting out of hand. People scaled high walls and clambered into seats for which others had paid. Such was the pressure on the ringside fences that they gave way. The crowd rushed across the large cinder track which encircles the playing pitch, and in an incredibly short time the beautiful greensward was occupied by a black uncontrollable mass. The police, apparently taken by surprise, were for a time powerless to deal with the situation and even after more officers, mounted and on foot, had been rushed to the ground, the task of clearing the playing pitch was a tediously slow process."

At 1.45 pm instructions were given for all gates to be closed. George Kerr later commented: "I saw the turnstiles had been built into woodern structures that were about 8 feet high, the turnstiles themselves were locked and deserted but bodies were climbing over them like monkeys and I quickly followed suit... I got behind the crowd and soon was being pushed forward by others who got behind me. I was literally pushed into the ground."

A reporter from the East Ham Echo described the scene after the gates were closed: "Something unusual was happening. Then the word went round that the disappointed multitude at the gates had broken through. They streamed down the little tributaries in a vast sea of heads, and settled on the cinder track round the pitch. Then came a sudden movement of the front ranks - a rush, the thin cordon of police and stewards was brushed aside like a cobweb, and in a moment the playing pitch, which had drawn the gaze for so long, brightly verdant in the sunshine, was blotted out - black with a restless, moving, excited throng of people. Football was forgotten. Spectators, who had taken up and held their positions since early morning, were bundled unceremoniously out of place by the rush, and swept on to the green. Everywhere men and women were seen clambering over the low rails and partitions, eager to secure seats in the stands. Strong men and frail women fainted and fell in the crush and excitement, and the ambulance brigade were hotly engaged in dealing with casualties which increased every minute."

Albert York was a barrow-boy who sold apples and pears to fans going to the game: "When everything was sold we went into the match through a broken gate and joined the heaving, sweating cloth-capped mass of humanity, but hardly saw a thing of the action because of the immense crowd."

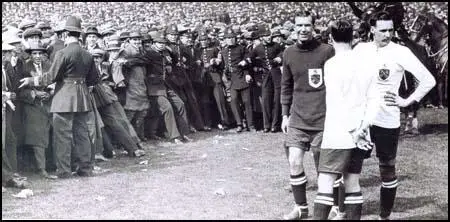

According to The Times newspaper, about a 1,000 people were injured attempting to get into Wembley Stadium that day. The spectators at the front were pushed onto the field making it impossible for the game to get started. For a while it seemed that the game would have to be postponed. However, in the words of one East Ham Echo reporter, "...then came the miracle. Half a dozen mounted policeman arrived on the scene, and working from the centre of the pitch by great efforts, filched a little more space from the crowd, which the cordon of police endeavoured to hold.... But wonders of wonders was the work of an inspector on a dashing white horse." The inspector on the white horse was G. A. Story and as a result of these efforts the game began after a 40 minute delay.

Jimmy Ruffell was later interviewed about the game: "Most of the people at Wembley seemed to be Londoners. Well, the ones I saw seemed to be. As we tried to make our way out onto the field everyone was slapping us on the back and grabbing our hands to shake them. By the time I got to the centre of the pitch my poor shoulder was aching."

West Ham trainer, Charlie Paynter, complained: "When the players of both sides got on the pitch there seemed quite a hundred London supporters to every Bolton supporter. My boys were slapped and pulled about, while the Bolton players got through practically unscathed. Unfortunately Ruffell, who had just got over an injured shoulder, which was naturally tender; and Tresadern both received severe shakings before they reached the pitch... It was a pitch made for us until folks tramped all over the place. when the game started it was hopeless. Our wingers, Ruffell and Richards were tripping in great ruts and holes... The pitch had been torn up badly by the crowd and the horses wandering over it."

The game eventually started 43 minutes late. In the second minute Jack Tresadern got stuck in the crowd after going in to retrieve the ball for a throw in. Before he could get back onto the field, the ball was sent into the West Ham United penalty area. Jack Young gained possession of the ball but he gave it away to Jimmy Seddon. The ball was then passed to David Jack. According to The Times reporter at the game: "Jack feinted to pass out to Butler; when the pass looked as good as made, he dribbled inside to the left, went through the West Ham United defence at a great pace and scored from close in with a hard high shot into the right-hand corner of the net."

Three minutes later, Dick Pym, the Bolton goalkeeper, missed a corner-kick from Jimmy Ruffell and the usually reliable Vic Watson, blasted the ball over the crossbar. The Times journalist covering the game wrote: "Pym, misjudging a perfectly taken corner by Ruffell, came out of goal and missed the ball. The ball came to Watson, who had an open goal yawning only a few yards in front of him. How he managed to kick the ball over the cross-bar instead of into the net one cannot imagine; if a player tried to do it, the odds against him would be generous. Watson, however, did fail to score."

Soon afterwards West Ham United had another chance when Dick Richards finished off a brilliant dribble with a clever shot that Dick Pym managed to save. After 13 minutes the game was brought to a halt after the crowd spilled on to the pitch in front of the main stand. It was another ten minutes before the mounted police cleared the pitch and the match could resume.

Once the game had restarted Joe Smith appeared to scored from a clever centre from Billy Butler but was ruled offside. Bolton were the better team in the first-half and the East Ham Echo reported that this was "because they were more experienced and better fitted temperamentally to stand the strains of the extraordinary conditions."

The teams did not leave the field at half-time but crossed over and resumed play after a five-rninutes' interval. West Ham United began the second half well and Vic Watson just failed to convert a cross from George Kay. This was followed by another near miss. According to George Kerr: "It was a hard low cross from Richards on the right wing arriving about chest-high outside the six-yard box. Watson went for it and had he contacted he must have scored but Pym, the goalie, managed to get his hand to it, knocking it down and collecting it."

In the 54th minute Joe Smith received a pass from Ted Vizard and volleyed against the underside of the bar. The referee ruled that it had crossed the line, before rebounding back into play. Bolton Wanderers now had a two-goal lead.

West Ham United continued to press forward but failed to make anymore chances. The Daily Mirror reported: "The prescence of the crowd on the touchlines considerably hampered the work of the wingers." Jimmy Ruffell later admitted: "It was a hard game for West Ham to play as the field had been churned up so bad by horses and the crowd that had been on the pitch well before the game. West Ham made a lot of the wings and you just couldn't run them for the crowd that were right up close to the line."

George Kerr supported this view: "The conditions did not suit West Ham. They relied heavily upon speed and the long ball, usually using Jimmy Ruffell plied by the other speed merchant Victor Watson. But it was clearly inhibiting to Ruffell with the danger of tripping over spectators' legs and the general feeling of being jammed in."

According to the Stratford Express: "It was a tame finish to a disappointing match, spoiled of all its interest by the lamentable conditions under which it was decided... Bolton won because they more nearly approached their more usual form than West Ham did, and because they were less upset by the unusual happenings. On the day's play they were the better side, and deserved their victory."

The Bolton Evening News agreed: "By general consent, West Ham were conquered by a team which played with superb confidence, plainly conscious of its ability to win through... Here we had eleven men working with but a single purpose, dovetailing and blending perfectly, a mobile, virile force which operated in absolute unison and unity, whether concentrating on aggression or compelled to retreat. I cannot single out one player more than another for a special need of praise. Where all did so well, it would be invidious to individualize."

After the game Syd King remarked that: "I'm too disappointed to talk. I want't to forget it." However, Charlie Paynter, the trainer, pointed out that Rule 5 was constantly broken during the FA Cup Final. "It is pure imagination for anyone to say that the touchlines were clear. They were not." Rule 5 states that the player making the throw-in has to be behind the touchline. This rarely happened during the game.

The East Ham Echo reported: "There is talk of a protest to the FA against regarding the game as the FA Cup Final, but disappointed and disatisfied as they must be with in the West Ham directors and their team are too good sports to do that." Syd King then issued a statement: "Although inundated with requests to lodge a protest against the result of the final tie, the directors of the West Ham club are satisfied that they were beaten by the better team on the day (under the conditions in which the match was played) but they do consider that the responsible officials of both clubs should have been informed at half-time as to whether the match was to be a Cup-tie or not; as in their opinion the match was not played under the rules of the FA (particularly with regard to Rule 5). Rule 5, deals with the conditions under which the ball shall be thrown from the touchline, but on Saturday the crowd were on the touchline practically all the time."

Only 48 hours after the final West Ham United had to play penultimate game in the 1922-23 season. The players held their nerve and beat Sheffield Wednesday at Hillsborough 2-0 with goals from Vic Watson and Billy Moore. The Hammers were top of the league on goal average. However, Leicester City and Notts County both had the same number of points. With only the top two going up, if West Ham lost their last game, they could still fail to get promoted.

The last fixtures of 1922-23 paired West Ham United with Notts County and Leicester City and Bury. Over 26,000 fans turned up to Upton Park to see the game against their promotion rivals on 5th May 1923. Although the home team pushed forward they found it difficult to create any real good chances. In the 38th minute, disaster struck as inside-forward, Harold Hill, put County ahead. The good news was that at Bury was leading Leicester City by a single goal at half-time.

George Kerr reported that "the second-half began much as before, with the Hammers striving hard but creating little in the way of scoring chances." The game at Gigg Lane had started 15 minutes earlier than the one at Upton Park and at 4.30 the West Ham fans began to look towards the North Bank. Kerr observed what was taking place: "The half-time scoreboard was situated in an elevated position at the rear of the North Bank. At the extreme right as we looked at it was a cubby-hole with a telephone and in which the operator was housed. We noticed that he was walking along the gang-plank to the opposite end and having reached it adjacent to the sign which would indicate the score of the Leicester City v Bury match, he marked the full-time result - 0-1 to Bury. Immediately the mood of the crowd was transformed from one of utter dejection to complete ecstasy."

West Ham was unable to score and the game resulted in a 1-0 victory to Notts County, who not only got promoted but had won the Second Division championship. However, West Ham had a better goal average than Leicester City and joined County in the First Division. It now became clear of the significance of the 6-0 victory at Filbert Street on 15th February. Without this result, it would have been Leicester who would have been promoted.

The form of the West Ham players had impressed the English selectors and both Vic Watson and Jack Tresadern were selected to play in the game against Scotland at Hampden Park. This was very unusual for Second Division players to be called-up for such an important game. Sid Bishop, Edward Hufton, Billy Brown, Billy Moore and Jimmy Ruffell also played for England over the next couple of years. Dick Richards was also a regular with Wales during this period. Eight of the West Ham team who played in the 1923 FA Cup Final became internationals. At 32 years old, George Kay, the West Ham captain was considered to be too old to be selected. Billy Henderson was called up to the England squad but a serious knee injury that brought an early end to his career stopped him from representing his country. The team had cost £2,000 in transfer fees. This was less than the £5,000 that West Ham had received for Syd Puddefoot. Like the other graduates of the West Ham coaching system, Puddefoot also went on to play for England.

The development of such a great team of youngsters was not lost on the major clubs of the time but West Ham refused offers for their stars and players like Vic Watson and Jimmy Ruffell remained at the club for many years.

Primary Sources

(1) Jimmy Ruffell, interviewed by Brian Belton in 1973.

The 1923 Cup final was unbelievable and there has never been a game like it. I had been tripped up in a game against Fulham at Upton Park by Tom Fleming and injured my shoulder and it was still giving me trouble on the day of the final. One or two of the boys were getting over injuries....

West Ham were a good club to play for. They still are. They looked after you. Bolton Wanderers were what football was all about. If you wanted to know what football was like in the 1920s, Bolton was it. Charlie Paynter said they had no real weaknesses, but West Ham was likely to move faster as a combination on a good pitch. While West Ham's back line wasn't probably as solid as Bolton's, we could move the ball through the team and quickly get to the last quarter of the field. West Ham were a good passing team. Most of the time you had an idea where men were or men would make themselves ready to get the ball from another player. I think we were one of the few clubs to really practice that. Then, with their good forward line, Vic Watson, Bill Moore and I was okay too, West Ham always had a chance at getting a goal. But when you lost the ball Bolton would nearly always make you pay. They were a team full of skill.

There's no point in going over the result, but it was a hard game for West Ham to play as the field had been churned up so bad by horses and the crowd that had been on the pitch well before the game. West Ham made a lot of the wings and you just couldn't run them for the crowd that were right up close to the line. Bolton had to play on the same field of course, but they didn't play so wide as West Ham. But there you are. It was history though.Syd King was a good manager. But he left a lot of the day-to-day stuff to our trainer Charlie Paynter. It was Charlie that most of us talked to about anything. Syd King was more about doing deals to get players to play for West Ham. But he was good at that. He got us to the Cup final and got West Ham promoted in 1923 so you can't ask for much more than that can you.Bolton were a big, famous club. It took the best part of a day to get up there then. West Ham were little compared to them. They had some top players. Vizard and Jack were good, as good as anyone at that time - they had a tough defence too. But we weren't afraid of them and we had some good boys too. Vic Watson was still very young, but he was strong as an ox and Jack Tresadern was an international. Billy Moore was very skilled and Ted Hufton was one of the best goalkeepers around. So, we thought we could beat them of course we did. But they were very good.Most of the people at Wembley seemed to be Londoners. Well, the ones I saw seemed to be. As we tried to make our way out onto the field everyone was slapping us on the back and grabbing our hands to shake them. By the time I got to the centre of the pitch my poor shoulder was aching.But it was wonderful just to be at Wembley. It really was. We enjoyed it even though West Ham lost. And when we got back to the East End everyone was happy and telling us how well we'd done. It was as if we'd won the Cup. Just as good as if we had. I think Bolton knew they had been in a game. Joe Smith, their captain, told some of us that it could have gone either way and he was right. And I met the King and he said it was hard luck on West Ham.But the best thing about it all was the thought years after that we had been there. People talked about that game for years after. They still do. It was a bit of a miracle that the game happened at all and certainly that people weren't killed. The thought that there could have been a disaster makes you just glad it turned out as it did. We were lucky. We deserved to be in the final, both West Ham and Bolton, but that everyone walked away from Wembley more or less in one piece was the biggest win of the day. People won the game really; more than either team.

(2) Brian Belton, The Lads of 1923 (2006)

Syd King had become the focus of an unprecedented level of media exposure during the build up for the Cup final as journalists grew ever more preoccupied with the Hammers' bargain priced team. The eleven selected to contest the biggest match in the club's history had cost a mere £2,025. So by 1923, what would become West Ham's reputation for succeeding without spending was already well established. But even by the Hammers' standards, the line-up for the Cup final that year was something of a bargain eleven. Only six of the players on show had cost more than £50. The sale of Puddefoot for £5,000 the previous season puts this in perspective. In contrast, Bolton, whilst not an expensive side to put together, were a team with pedigree, worth at least as much as any side in the world. The Wanderers' run up to the final had been much more low key than their opponents, they had an almost military attitude to the task in front of them; they tended to move as a unit with a defensive artillery supplying long range assistance to an attacking cavalry that worked together with a rehearsed discipline. This resulted in a style that could steamroll and cut apart sides by breaking through their ranks at the weakest point.

(3) The Stratford Express (17th January, 1923)

West Ham United gained a smart and well merited victory over Hull City at Hull on Saturday in the FA Cup competition by three goals to two. The stronger and faster side, West Ham infused a dash and energy into their play which gained them the victory. Hull City, however, did not go down without making a grim struggle, but they were beaten by a superior all round combination. The game produced plenty of excitement throughout, and was sensational in its opening. The West Ham forwards early got to work, and catching the home defence unsettled took the lead in the first four minutes...

West Ham's attack was superior to that of the City, the forwards finishing their movements much better. Moore and Watson were very prominent and Kay at centre-half did much to destroy the effectiveness of the home attack.

(4) The East Ham Echo (9th February, 1923)

Within three minutes after the game was resumed, there was a desperate scrimmage in the Hammers goal mouth, Hufton left his charge and missed the ball, managed to get back, but the ball kept bobbing about, until Cook headed it into the net for Brighton. The impression from the stand was that he was offside, but the referee was in an excellent position to see, and he never hesitated. Brighton played up with rare dash for a time after that but West Ham were soon on top again, and the subsequent play was all in their favour, though Kay, their centre, was injured having strained a thigh muscle which caused him to retire, and the team to be reshuffled. Bishop took his place at centre half, and Brown dropped back from the front line to right half.

Watson equalised the score with a fine low shot twenty-five minutes through the second half, and the game went to the end with the score 1-1.

(5) The Stratford Express (12th February, 1923)

West Ham qualified for the third round of the FA Cup on Wednesday afternoon at Upton Park by defeating Brighton in their replayed tie by the only goal scored three minutes before the interval. Although but one point was registered that so reflected the run of play. West Ham were by far the superior side and Brighton were fortunate to escape with such a narrow defeat. The conditions underfoot were against accurate football, but the West Ham players exhibited better combination and control of the ball than their opponents...

The success was no more than West Ham deserved and subsequently, but for robust and steady defensive play by Feebury and Thompson at back, further goals would have accrued. These two players, with the goalkeeper, bore the brunt of the battle so far as Brighton was concerned. It was always more or less a duel between them and the home attack. Their forwards were ineffective in attack, their movements being spasmodic and mostly individual. They were well held in check by the home half backs of whom Tresadern was the pick. In fact, he was the best half back on the field. His tackling was well timed, and his control of the ball and accurate distribution were wonderful on the slippery turf.

Hufton, in goal, without having much to accomplish was always on the alert, and on two occasions this alertness saved the situation for his side. Watson, at centre forward, led the forwards well and distributed the ball to advantage, and he found Moore and Ruffell on the left his most able supporters. On the play West Ham were easily the better side.

(6) The Stratford Express (28th February, 1923)

Had West Ham United beaten Plymouth Argyle by a larger margin than 2-0 at Upton Park on Saturday in the third round of the FA Cup, it would have been no more than they deserved. They won their way into the fourth round by a masterly and convincing display of football in which the whole team was seen to advantage. As a combination of players they were far superior to the visitors, whose forwards were disappointing. Their efforts throughout lacked cohesion, and probably this was mainly due to the effective work of the home half back line, from which Kay was an absentee. The honours on the visitor's side undoubtedly went to the defenders, who gave a heroic display against an attack which was virile and clever. Well as the half backs played, however, they frequently failed to break up the clever combination of the home forwards, and only unhesitating tackling by Russell and Forbes, and alertness by Craig in goal kept the score down.

Considering the conditions underfoot the game was of a remarkably high standard and one that was played in a fine sporting manner. The play held the spectators from start to finish and, although the visitors were beaten, they did not give in easily. Their chief failure was in attack, which was poor in comparison with that of the home team. There was unselfishness about the play of the latter which was quite refreshing. The main desire of each player always seemed to be to part with the ball to the best advantage, and in this respect Watson, at centre-forward, stood out. He was opposed by a centre-half in Hill who, like himself, is a candidate for international honours. There were some fine duels between them, and Watson delighted his admirers by frequently beating his lengthy opponent in the matter of cleverness. The centre-forward opened out the game and distributed the ball in clever fashion and he was well supported by his colleagues.

Ruffell, at outside-left, was particularly clever, and there was no better forward on the field. He hardly ever failed to use the ball to advantage, and his quick runs along the wing and his well-timed and accurate centres were a constant source of danger.

(7) The Stratford Express (23rd March, 1923)

A single goal scored eighteen minutes from the end was sufficient to take West Ham United into the semi-final of the FA Cup for the first time in the history of the club. They met Southampton for the third time in an endeavour to decide who should meet Derby County, on the Aston Villa ground, Birmingham, on Monday, before 22,000 spectators. Neither side can be said to have set the place on fire by their play and it was fairly obvious after the first fifteen minutes that the players were feeling the effects of having played two strenuous cup-tie games and a league match in the previous nine days.

The football was poor throughout, but of the two teams, both cup-tie weary, West Ham were slightly the better and just about deserved their victory. It was at half back where they were superior, and because of this and the support given to the forwards they were superior in their method of attack. There was more cohesion in the front line than shown by the Southampton forwards, but even so they were invariably as bad at finishing as Southampton. The honours on the latter's side again went to the defence where Parker and Titmuss retrieved the many faults of the halfbacks admirably. As a line the Saints middlemen were not nearly so good as the West Ham halves. Watson was allowed yards of room by Campbell, who indulged in plenty of hefty wide kicking, but afforded little help to his forwards. In the circumstances it was surprising more was not seen of Watson, unless he was as much off colour as the Southampton centre-half.

The outstanding players on the field were undoubtedly Kay and Tresadern. The former returned to his position at centre-half for the first time on Saturday, since the first match with Brighton in the second round of the cup when he was injured. In Monday's game he completely dominated Rawlings, the Southampton centre-forward, as well as opening out the game for his own forwards. It was mainly due to the way in which he subdued Rawlings that the Southampton front line was so ineffective, the centre-forward seldom getting a chance to distribute the ball to the wings. Brown at outside right was the only Southampton forward to cause any anxiety to the West Ham defence, but he could not overcome the defenders single-handed. In a few words, both attacks were inefficient against defences which often played listlessly. Play throughout lacked vim, and much of the football was crude. There were a few exciting moments as the players struggled on through the game, tired and weary.

In fairness to the players it must be remembered that, in addition to playing so frequently recently, they found the pace of the ground much faster. For weeks and weeks they had been ploughing their way through mud, but the Aston Villa ground was dry, and the ball travelled at a pace which was too fast for tired men.

(8) The Daily Mail (26th March, 1923)

West Ham have never played finer football. It was intelligent, it was clever, and it was dashing. They were quick, they dribbled and swerved, and passed and ran as if the ball was to them a thing of life and obedient to their wishes. They were the master tacticians, and it was by their tactics that they gained... Every man always seemed to be in his place, and the manner in which the ball was flashed from player to player - often without the man who parted from it taking the trouble to look - but with the assistance that his colleague was where he ought to be - suggested the well-assembled parts of a machine, all of which were in perfect working order.

(9) The Bolton Evening News (26th March, 1923)

West Ham United gave a superb display beating Derby County, whose defence, hitherto unbeaten in the Cup competition, was penetrated on five occasions. In this match, regarded as an ordeal likely to upset the normal play of the best organized side, the West Ham men played as they never did before, even in a season during which the club's previous best achievements have been eclipsed. They reduced to impotence the men who had overcome London's supposed strongest side. The conquers of Hotspurs a fortnight before were out-classed in every particular.

Perhaps Moore was the cleverest attacker, but Richards, outside-right, and Watson, the centre, completed a line which brought out the best features of amateur and professional football. All the men were exceedingly quick in taking the ball in their stride, fast on the run, clever in dribbling and sure in passing low or opening the game as the occasion demanded. West Ham used every method of attack to get through the defence. Tresadern and Kay, in the half back line - indeed, the whole winning eleven - played splendidly.

(10) The Stratford Express (28th March, 1923)

Saturday was a great day for the West Ham United FC. For the first time in its history it succeeded in reaching the final of the FA Cup. As the last hope of London being represented in the first final to be played at the immense new stadium at Wembley.

Intense interest centred upon the club's meeting with Derby County at Stamford Bridge and Londoners were overjoyed at the success of the team. The whole team played inspired football. No other combination of players has ever accomplished such a fine performance for the club and their victory by 5 goals to 2 was gained by a masterly and brilliant display of football which, if reproduced in the final tie should result in the Cup coming to West Ham. It was said that Derby County did not produce the form that enabled them to defeat Tottenham in the fourth round, but a team usually plays as well as the other side allows, and in Saturday's game the Derby team were outplayed and out manoeuvred. Their forwards were generally well held by the West Ham half backs, who gave a brilliant display and successfully negated attack after attack. The outside wingers were the County's most dangerous players, but the inside men were so well watched that they were not allowed to develop the movements. The West Ham defence was usually master of the situation, and except for one period of slackness in the second half when leading by four clear goals, played with confidence and ability.

The change in the type of football from that which the team played the previous Monday at Birmingham was amazing. Then we saw a tired team trying in vain to keep up with the ball. On Saturday we saw a team working together like a well-oiled machine, full of vitality in attack, confident in its methods, accurate in its execution and driving home its advantages to the full. The Derby defence was continually harassed by a forward line which would have tested the best defence in the country. There was method and precision in everything it did, and its deadly accuracy was confirmed by the fact on five occasions it beat a defence which in the previous four rounds had not given away a goal. This made the achievement all the more remarkable. Right from the start the forwards were on top of the Derby defence. Watson, although he did not actually get a goal, has seldom played a more effective game. His tactics of lying well up the field between the backs brought about the downfall of the Derby goal on two occasions, but in addition he did what a real leader should do, he led the line and kept the wings well supplied with the ball. There was no cleverer player on the field than Moore, the West ham inside-left, and his second goal a couple of minutes after the interval was one that will live in the memory of the club's supporters for many a day. He must have beaten nearly every Derby defender single-handed before putting the ball into the net.

The power of their half back line meant a lot to West Ham. Each half was a defender and an attacker. As a line they were splendid. Galloway, the Derby centre-forward, was seldom able to get away from the attentions of Kay, who played a masterful game. Bishop, too, did exceedingly well against the Derby crack wing, Murphy and Moore, who usually threatened what danger there was in the Derby attack, but nobody on the field played better than Tresadern. His tackling and passing of the ball were well-nigh perfect, and he earned golden opinions. Henderson and Young at back, thanks to the effective work of the halves, had an easy time compared with the Derby backs, and Hufton, in goal, had little to do. On the two occasions the ball entered the net he had no chance.

The Derby attack as a line was disappointing. They finished badly and missed several opportunities. Except for Murphy the outside-left, an exceedingly fast and clever player, they were easily dispossessed. They were, however, not supported well by the half backs, whose passing was faulty. Thorns, the centre-half, was not nearly fast enough or watchful enough so far as Watson was concerned, and the backs were thus constantly harassed. Of the two Chandler put up a great defence against a clever wing in Ruffell and Moore, and was as good as any of the backs, but Crilly was often uncertain and threw a lot of extra work upon his partner.

(11) The East Ham Echo (6th April 1923)

West Ham United, of whose fine performances on the football field everybody is talking about now, and who are being confidently named as certain winners of the English Cup in the first final at the great new Stadium at Wembley, have made a splendid holiday record. It was rather disappointing for the biggest crowd seen on the Boleyn ground (30,000) at Upton Park on Good Friday, that they did not more than draw in their League match with Bury. It was a game with many thrills, but no goals.

But they made up for it the next day at Selhurst when they ran up five goals to one against Crystal Palace. There was a crowd of 18,000, and the Palace band greeted the Hammers with the strains of "See the conquering hero comes." It was a nice compliment to the Cup finalists, and they showed that they appreciated it by starting a winning score by putting up two goals in eight minutes. Tresadern, from the half back line, and Ruffell, from the left wing, were resting, their places being taken by Makesy (half back) and Edwards (left-wing). The Selhurst ground is somewhat rough, but the Hammers quickly adapted themselves to the conditions. Watson, the centre forward, got the first goal, and Brown followed suit directly afterwards. Then Watson scored three more off the reel, two before the interval, and one afterwards. Meantime the Palace had obtained a little solatium in a goal, headed in from a corner kick. With five goals to one, the Hammers eased up. They had given the Palace a gruelling time, and for the rest of the game they took things quietly, contenting themselves with keeping a disorganised side from getting any more goals against them.

At Bury on Easter Monday there was a holiday crowd of 25,000 to welcome the Hammers for the return match, but any hope they might have had from the drawn game at Upton Park of seeing Bury bring discomfiture to the West Ham team was dispelled as the game progressed although Bury made a very encouraging start.

Within a couple of minutes of the start, Hufton had to deal with a penalty shot. He stopped it, but could not get the ball away, and Burkinshaw headed a goal. Ten minutes later Bullock, the Bury centre, got another and the crowd was in high glee. But events took a sudden turn. Watson reduced the lead before the interval, and when the game was restarted for the second half, things began to hum. In three minutes Richards had equalised, turning into goal a shot sent in by Watson, Kay (centre half), put them ahead a minute later, Watson headed a forth goal and Ruffell completed West Ham's tally with a fifth. Bury were in a hopeless position long before the finish. The Hammers had matters much their own way and the home goal had many thrilling escapes.

There was a large contingent of the Wanderers from Bolton on the ground at Bury, and they went away profoundly impressed with the form of the Hammers, and cogitating on Bolton's chances against them in the final.

Two great objects the Hammers have now before them - the English Cup and League honours! With such wonderful form as they have shown in recent matches, the Cup comes nearer every day! And they are well in the running for promotion. With three games in hand, the results of the holiday matches have vastly improved their already good goal average, and brought them within four points of the Second League leaders, Leicester City. Leicester have gained 46 points, but have a lower goal average. Blackpool are third with 43 points, Fulham fourth also with 43 and West Ham fifth with 42 points from 34 games.

The Hammers have a pretty hot programme to the end of the season as they have to meet Notts County, Fulham, Hull City, Barnsley and Sheffield Wednesday. But they have cleared a good many stiff fences with ease lately, and if they maintain their present form there is no need for any anxiety as to their ability to bring off the great Double. They have not lost one of the twenty matches they have played in the League or the Cup competition since Boxing Day, when they dropped two goals at home, unexpectedly to Manchester United after beating them 2-1 at Manchester the previous day. And in those twenty matches they have scored 43 goals, and only had 16 scored against them.

(12) The East Ham Echo (4th May 1923)

West Ham United, of whose fine performances on the football field everybody is talking about now, and who are being confidently named as certain winners of the English Cup in the first final at the great new Stadium at Wembley, have made a splendid holiday record. It was rather disappointing for the biggest crowd seen on the Boleyn ground (30,000) at Upton Park on Good Friday, that they did not more than draw in their League match with Bury. It was a game with many thrills, but no goals.

(13) Bolton Evening News (30th April, 1923)

It had been confidently stated that this new amphitheatre, the home of English sport, was structurally and scientifically perfect, offering comfortable accommodation and an unobstructed view to upwards of 125,000 spectators. Clearly the authorities were totally unprepared for what happened. It is computed that fully 250,000 people made their way to the imposing and spacious ground form all parts of the Empire, all anxious to see the blue riband of the football world decided. About 60,000 people had passed inside the turnstiles when pandemonium broke loose.

One of the main exits was broken down and thousands of people surged inside the enclosure, and from that moment the situation showed signs of getting out of hand. People scaled high walls and clambered into seats for which others had paid. Such was the pressure on the ringside fences that they gave way. The crowd rushed across the large cinder track which encircles the playing pitch, and in an incredibly short time the beautiful greensward was occupied by a black uncontrollable mass. The police, apparently taken by surprise, were for a time powerless to deal with the situation and even after more officers, mounted and on foot, had been rushed to the ground, the task of clearing the playing pitch was a tediously slow process. Indeed, when the players came into the arena, there seemed very little prospect of the game being started. finally, however, when the players added their persuasion to the force resorted to by the constabulary, the crowd was gradually pressed back to the touchline, and at 14 minutes to four the referee found it possible to make a start.

The Bolton party made the Russell Hotel their headquarters for the weekend, the players with the manager, Mr E.B. Foweraker, having spent the last few hours before the match at Harrow, and they made the short journey to the ground in excellent time. But the directors and their friends, who journeyed from London in charabancs, had an experience they will never forget. They certainly have no desire to see Wembley again. The road was packed with vehicular traffic for long stretches trams, buses, charabanc, motors and horse conveyances were running four abreast, and frequently were held up for long periods at cross roads. The journey occupied two hours - and when the party had to alight, fully half a mile from the vast amphitheatre, many of us had abandoned hope of seeing any play in the first half. With scores of others, I made my way across a grass field, crossed a railway, scaled a high wall, and then found my way into the enclosure obstructed by corrugated iron hoardings with three rows of barbed wire above them. Some of the more daring spirits surmounted this formidable obstacle, whilst others less venturesome burrowed under the hoardings only to find more difficulties ahead. Nobody seemed to know how to get inside the enclosure, and there were thousands of people shut out. It was my good fortune to reach the Press seats at the top of the north stand at 3-40, and then greatly to my relief I learned that the match had not started.

Dozens of Bolton people saw none of the game. None of the directors saw the first goal, and several of them did not get as much as a glimpse of the game. Scores of people who had paid a guinea for a seat never got it. Never in the history of the game has there been such a tragedy, and for the credit of those who are responsible for the good government of Soccer, the most popular of all pastimes, it is to be hoped it will never be repeated. The Football Association have since disclaimed any responsibility for what happened. They point out that all the arrangements were in the hands of the Wembley authorities. I venture to suggest the FA are merely begging the question by taking such an attitude. The public look up to the FA, and indeed to every football body, to keep faith with them, and such a debacle as this will do unquestionable harm to the game. The invasion of the playing field was due, it is alleged, to the snapping of the barriers when the in rush of spectators followed the breaking-in of the gates.

(14) The Times (30th April, 1923)

The Bolton Wanderers beat West Ham United in the Cup Final at the Wembley Stadium on Saturday by 2 goals to 0.

This bald statement represents the result of the football side of a matter which has been discussed from many points of view for months. The fact that the Wembley Stadium has been advertised as the greatest of its kind had much to do with the enormous crowd which came from all sorts and conditions of places to see the first Cup Final to be played there. The claims made for the Stadium were not in the slightest degree extravagant. It was built to hold 125,000 people in comfort and to give to each and every one of that huge total a fair view of the football ground and track. The Stadium can hold even more than that number, and yet give to all the spectators a fair view, but no building and ground could accommodate 300,000 people, and at least that number must have turned up on Saturday at Wembley.

The reasons for the mammoth congregation were many. The opening of the Stadium for the first Cup Final might become - as in fact it has become - an historic occasion. There was the fact that a London club were in the Final Tie; the day was perfect; and, by the irony of fate, the superb organisation of the many railway lines converging on the stations round the Stadium was the crowning factor in producing such a crowd that it was impossible for any arrangements there to be carried out according to plan.

Except on two important points - the spirit of the people and of the police, and the absolute loyalty, of a very mixed congregation, to the King - the day was an ugly one. Many ticket-holders never reached their seats; others got to their seats in plenty of time and were pushed out of them; whirled away like straws on a stream by the sheer weight of numbers sweeping irresistibly forward from behind. The crowd was out of hand, very often most unwillingly. By 2.30 p.m. many people were attempting to get back the way they had come, the one more difficult thing than pushing on as indeterminate atoms of the throng. The playing-ground on Saturday morning was a beautiful picture. Later on, there must have been tens of thousands of people on it at one time. It was defiled with orange peel and papers and refuse, but the surface stood the trampling of the mob, the police, and the hoofs of the horses of the mounted police most astonishingly well. Many of the thousands on the field of play were not there of their own volition - they were whirled away from seats and places of vantage secured by patient waiting. By the help of large reinforcements of police, mounted and unmounted, and the players, who appealed right and left for fair play, the ground was gradually cleared, the people being pushed back to the touch-lines. That play could ever be begun and continued seemed, at one time, quite impossible. That the seemingly impossible could and did happen was, one must believe, owing to the presence of the King, whose reception when he reached the ground was an event to remember. It was after "God Save the King" had been sung with boundless enthusiasm that the people began, slowly enough, it is true, to help rather than to hinder in the clearing of the ground.

At 3.45 it was possible to kick off. Some eleven minutes later, a part of the crowd were squeezed on to the ground, but play was again possible after ten minutes' patient work on the part of the police. The Bolton Wanderers were leading at the time by one goal to none, having scored in the first two minutes; but, five minutes before the second interruption, West Ham United had nearly equalised, Watson missing a chance which he would have taken with absolute certainty on an ordinary occasion.

Taken merely as an Association Football match, the play at Wembley on Saturday was rather disappointing. No doubt, the long wait and the doubt as to the possibility of the game being finished, even if begun, had an effect on players already keyed up to a high state of tension. To win a Cup-tie medal is preferred, by quite a many, to winning an international cap. West Ham United had not only been preparing to win the Cup, they had also, if possible, to force their way into the League Championship next season. The double event has proved beyond their powers, but they certainly deserve promotion on the season's play. They were a good side for the first ten minutes of the great final, but, afterwards, they were never convincing. When the sun was against them in the first half both the backs and the half-backs kicked too high and too hard. In the second half, when the sun was shining in the faces of the Bolton Wanderers' defence, the high kicking, followed by a rush, with all the forwards in something like a line, might have proved extremely good tactics. The Bolton Wanderers' backs and half-backs, however, seldom had to use their heads for safety in the second half. The game was started at a great pace, and the Bolton Wanderers scored after just two minutes play. Nuttall dribbled up the field, half drew a man, and passed perfectly to Jack. Jack took the ball along slowly and feinted to pass out to Butler; when the pass looked as good as made, he dribbled inside to the left, went through the West Ham United defence at a great pace and scored from close in with a hard high shot into the right-hand corner of the net. Hufton could strike only at the direction in which he hoped the ball would take, and he cannot be blamed for letting the ball pass him. Three minutes later came the great chance for West Ham United to equalise. Pym, misjudging a perfectly taken corner by Ruffell, came out of goal and missed the ball. The ball came to Watson, who had an open goal yawning only a few yards in front of him. How he managed to kick the ball over the cross-bar instead of into the net one cannot imagine; if a player tried to do it, the odds against him would be generous. Watson, however, did fail to score.

West Ham United were every bit as good as their opponents until the second stoppage of play occurred. Even when the match was continued the crowd were actually on the touch-line and sometimes over it. The West Ham United outsides never showed confidence near to the crowd ; one was reminded constantly of the speech of the Maltese Cat on the subject of crowding in Rudyard Kipling's wonderful polo story, called after the great pony. Now Vizard seemed to enjoy the human wall which marked or obliterated the touch-line. On an ordinary day Bishop might have held him; in the circumstances his mentality was at fault, for which he is scarcely to blame. Richards made one brilliant dribble and break through for West Ham United and Pym fumbled a clever shot, though he eventually cleared comfortably. A little later a beautiful centre by Vizard was headed just wide by J. R. Smith. Bolton Wanderers continued to attack, and J. R. Smith scored from a clever centre from Butler. J. R. Smith was ruled offside, although he appeared to be well behind the ball when it was kicked. The Press Stand, however, is some distance in mere yards from the field of play, and the angle was not easy to judge. Until half-time Bolton Wanderers were always the more dangerous combination, and, but for the magnificent game which Henderson played at right full-back, they would probably have scored again on at least one occasion.

The teams did not leave the field at half-time - if they had done so, the match would not have been finished on Saturday - but crossed over and resumed play after a five-rninutes' interval. West Ham United began the second half well, and Watson had a good chance from a centre of Kay's, the centre-half having worked out on to the wing with a clever individual effort. Watson, however, misjudged the flight and direction of the ball and did not start for it in time. Pym saved two shots quietly and confidently and then came the movement that settled the result of the match. Vizard niggled the ball down the wing, very close to the touchline. Suddenly he kicked and ran, passed Bishop and centred right across the goal mouth. J. R. Smith got to the ball and shot immediately. The ball hit the inside of the cross-bar and bounced out again into play. It was, however, a goal and the referee had not the slightest hesitation in ruling it as such. Even before this goal was scored a rivulet of spectators were leaving the ground; now this rivulet swelled to a steady stream. The match, to all intents and purposes, was over.

Bolton Wanderers, on the day's play, were always the better side after the first ten minutes. They did not realise the hopes of the big contingent of their supporters, whose Saga, after the second goal was scored, "One, Two, Three, Four, Five", was repeated mechanically and at brief intervals until the finish. Seddon, the Bolton Wanderers centre-half-back, carried off the honours of the match. He called the tune to his side, and generously they piped. All of them could be picked out for good work, at times for brilliant work; but the other ten would be the first ten to award merit where merit was due, and would fasten on Seddon as the ultimate winner of the F.A. Cup.

At the finish of the match the King presented the Cup to J. Smith, the captain of the Bolton Wanderers, and the medals to the different players. He drove away amidst a scene of heartfelt enthusiasm.

(15) Bolton Evening News (30th April, 1923)

Comments on the collective and individual merits of the players must be brief. By general consent, West Ham were conquered by a team which played with superb confidence, plainly conscious of its ability to win through. The Wanderers went about their work right from the outset in a manner which seemed to suggest "We are bound to beat the best team in the Second Division if only we play our natural game." It was what is known as one of the most valuable asserts any combination of footballers can develop - team spirit - that pulled the "Trotters" though. Here we had eleven men working with but a single purpose, dovetailing and blending perfectly, a mobile, virile force which operated in absolute unison and unity, whether concentrating on aggression or compelled to retreat. I cannot single out one player more than another for a special need of praise. Where all did so well, it would be invidious to individualize. Suffice it to say that in a comparatively quiet afternoon, Pym made one thrilling save, and displayed fine judgement and anticipation; that the two young backs, Haworth and Finney, never faltered; that Seddon, a giant in every phase of the game, had two polished wing halves as colleagues, and that the whole forward line worked together untiringly and with no little skill to lead and lure the "Hammers" rear-guard into false positions. There was nothing of the "hammer-your-way-though" policy about the Bolton attacks.

(16) The Stratford Express (2nd May, 1923)

There was every prospect, under normal conditions, of witnessing one of the finest exhibitions ever seen in a final for the Cup, but in the circumstances neither side showed its best form. Bolton won because they more nearly approached their more usual form than West Ham did, and because they were less upset by the unusual happenings. On the day's play they were the better side, and deserved their victory. They were better together as a team, and displayed more understanding. Their passes did not go astray so much as those by the West Ham players, on whose part generally there was a singular lack of enterprise. It was fairly obvious that they were upset by the day's happenings, and the two wingers, Richards and Ruffell, only occasionally showed flashes of speed. They did not at all relish playing on top of the spectators. On the other hand, Vizard, the clever Bolton left winger, seemed not in the least perturbed, and it was from him and J.Smith that most of the trouble came for the West Ham defence. Bishop and Henderson stuck to their task against these two with great perseverance, without always being able to stop their progress. Generally, however, the defence did well, although two goals were scored against it. The real reason of the side's downfall was because of the weakness in finishing and lack of enterprise on the part of the inside forwards. The wing men were cramped for room mostly, but Watson was nearly always dominated by Seddon, the Bolton centre-half, and Moore and Brown, the inside wingers, failed to take advantage of the constant shadowing of the centre-forward. The Bolton backs were tireless tacklers and clean in their kicking and performed in combination with the half backs.

(17) Syd King, statement (5th May, 1923)

Although inundated with requests to lodge a protest against the result of the final tie, the directors of the West Ham club are satisfied that they were beaten by the better team on the day (under the conditions in which the match was played) but they do consider that the responsible officials of both clubs should have been informed at half-time as to whether the match was to be a Cup-tie or not; as in their opinion the match was not played under the rules of the FA (particularly with regard to Rule 5). Rule 5, deals with the conditions under which the ball shall be thrown from the touchline, but on Saturday the crowd were on the touchline practically all the time.

(18) East Ham Echo (11th May, 1923)

Saturday afternoon brought hot summer like weather. Football was clean out of season, so to speak, and the young man's fancy turned lightly to thoughts of flannels and cricket.

But there was grim earnestness about the game at the Boleyn Ground at Upton Park. It was the last League match of the season, and a crowd that filled the ground and caused the gates to be closed some time before the start, were roused to the keenest pitch of excitement and enthusiasm in the struggle which went on between West Ham and Notts County for ninety minutes without slackening to decided League honours and promotion.

The Hammers started with three chances. If they won they would go to the top of the Second League as champions, and secure promotion to the First League; if they drew they still had a chance of being champions, if Leicester failed at Bury; and if they lost, the Hammers had yet the chance of promotion, in the event of Bury being victorious. For Notts County, too, the issue was vital, as a win meant their return to the First League after a season in the Second Division.

As it turned out, the Hammers failed through not taking the chances of scoring which came to them in the early stage of the game, and Notts County won by the only goal scored. Yet if it was a deep disappointment to the Hammers and their supporters to lose where they should have won this last match of the season, upon which so much depended, there was comfort for them in the news which came through that Leicester had lost to Bury, and they were sure of promotion after all.

The news of Leicester's loss that meant West Ham's gain was signalled from the veranda of the directors' pavilion while a fierce struggle was going on round the Notts goal, a few minutes before the end of the match. Immediately there was a cheer, which swelled into a mighty roar as it was taken up by the crowd all round the ground. For the moment the players were confounded and the play seemed to hang in suspense, but, immediately the meaning of the burst of enthusiasm became apparent, the Hammers found new spirit for jaded energies in the cheers which welcomed the fact that they had gained promotion to the premier division of the League.

It was a thrilling scene, and an interesting touch was added to it when Donald Cook, the Notts County centre, found opportunity on the field to shake hands with George Kay, the West Ham captain.

As we have said, the news came when the Hammers were fighting hard against fortune to save what had already become for them a lost game. They ought to have won it in the first quarter of an hour, if they had taken advantage of the chances which were presented to them. The first came to Moore, the usually sure shooting inside left, who had the ball in the Notts' goal-mouth two minutes after the kick-off, but weakly lobbed it into the goalkeeper's hands. A few minutes later Watson, the home centre, finished a glorious run down the centre of the field, in the course of which he beat half-a-dozen opponents, by ballooning the ball over the bar when he might also have walked it in. And just as disappointing was Ruffell's attempt two minutes afterwards, when from almost the same fatal foot of the ground in front of the Notts goal, he also skied the ball over the top.

Any one of those three easy chances converted into a goal would have made all the difference to the match, but after Notts at the first, and almost only opportunity given to them had scored their goal they put up such a hustling, bustling fight to keep what they had got that there never seemed any likelihood of the Hammers catching up. They fought hard and strenuously in the sweltering heat and made ground assaults on the Notts goal, ranging round it for minutes together, but the burly Notts' defenders did not stand on ceremony, and were not at all particular in their methods. Time and again they were penalised and once when Watson was brought down very badly on the penalty line when he was in "full cry" for goal, the crowd shouted in indignation. The referee consulted the linesman, and gave a free kick just outside the penalty area.

But Notts escaped from it, and the game went on with more feeling put into the play, and in the closing stage there was something of a scene, in which Iremonger, the lengthy goalkeeper, figured. All through the game he had shown much of his old failing of childlike irritation and protest, and when he squared up to one of the West Ham forwards, two or three players took the matter up, and there looked like being trouble. Happily peace was restored, and the incident passed.

Despite all the Hammers' efforts, Notts held their one-goal lead to the end, and with it gained the championship of the division. West Ham take second place on goal average, and go up with them to the First League.

It would have been much more satisfactory from the Hammers' point of view, of course, if promotion had come to them through success in their last match, instead of through the failure of another club, so to speak, but in any case promotion was due to them on a very fine record. Runners-up for the FA Cup and for League honours, they are to be heartily congratulated on a strikingly successful season.

West Ham have never previously been in the First Division. After playing for many years in the Southern League, they were elected to the Second Division in 1919, and in the first season finished seventh with 47 points, and this season's record of second place and promotion with 51 points adds to the story of constant progress.