Vavasour Powell

Vavasor Powell, the son of Richard Powell, was born in the parish of Heyope, near Knighton in Radnorshire, in 1617. Penelope Powell, Vavasor's mother, was the daughter of William Vavasor of Newtown. Her grandfather had been sheriff of the county in 1564. Powell was probably educated at Christ College, Brecon. Powell was never ordained in any of the orders of the Church of England, but probably worked as a schoolmaster in Clun. Powell had begun preaching by 1640 and in that year was arrested with fifty or sixty hearers for causing a disturbance through preaching.

On 2 February 1642 Powell married Joan Quarrell. Later that year he was charged with nonconformity, but was found not guilty. He moved to England anf he eventually settled in Dartford, in Kent, where he was vicar in around 1643. On the outbreal of the English Civil War he supported Parliament against Charles I. (1)

At the beginning of the war, Parliament relied on soldiers recruited by large landowners who supported their cause. Oliver Cromwell soon realised that these soldiers would not be good enough to defeat the Cavaliers. He pointed out in a letter to his cousin, John Hampden, about his regiment: "Your troopers are most of them old decayed serving men... the royalists' troopers are gentleman's sons, younger sons, persons of quality. Do you think that the spirits of such base and mean fellows will be ever able to encounter gentleman that have honour, courage and resolution in them? You must get men of a spirit... that is likely to go on as far as a gentleman will go, or else I am sure you will be beaten still." (2)

Cromwell recruited men who shared his "Puritan religious zeal". He also imposed strict discipline. When in April 1643, two troopers tried to desert, he had them whipped in the market place. Men who was heard to swear they would be fined "twelvepence; if he be drunk he is set in the stocks, or worse". Cromwell was careful about who he selected as officers. The Earl of Manchester complained that he did employ "men of estates" but "common men, poor and of mean parentage". He added that they were always very religious men. (3)

Vavasour Powell and the New Model Army

In February 1645, the House of Commons decided to form a new army of professional soldiers. This became known as the New Model Army. It was made up of ten cavalry regiments of 600 men each, twelve foot regiments of 1,200 men, and one regiment of 1,000 dragoons. General Thomas Fairfax, was appointed as its commander-in-chief. The new army contained a larger number of ideologically-committed soldiers and officers than any other army that had taken the field so far. Cromwell was quoted as saying: "I would rather have a plain russett-coated captain that know what he fights for, and loves what he knows, than that which you call a gentleman and nothing else." (4)

In 1646 Powell left Dartford to join the New Model Army forces besieging Oxford, having resigned from his living. On 11th September he received a certificate of approval from the Westminster assembly as to his fitness for the ministry in Wales and his ability to preach in Welsh. In June 1648 he was awarded maintenance from the tithes of six Montgomeryshire parishes to preach in the north Wales counties. He attached himself to the army of Thomas Mytton, and was injured at the siege of Beaumaris in October 1648. "In the heat of the action he heard a voice telling him that he was chosen to preach the gospel; he later attributed his survival to divine intervention on account of his calling." (5)

On the 30th January, 1649, Charles I was taken to a scaffold built outside Whitehall Palace. Charles wore two shirts as he was worried that if he shivered in the cold people would think he was afraid of dying. He told his servant "were I to shake through cold, my enemies would attribute it to fear." Troopers on horseback kept the crowds some distance from the scaffold, and it is unlikely that many people heard the speech that he made just before his head was cut off with an axe. The executioner then took up the head and announced, in traditional fashion, "Behold the head of a traitor!" At that moment, according to an eyewitness, "there was such a groan by the thousands then present, as I never heard before and desire I may never hear again." (6)

The Commonwealth

The House of Commons now passed a series of new laws. They abolished the monarchy, on the grounds that it was "unnecessary, burdensome and dangerous to the liberty, safety and public interest of the people" and the House of Lords as "it is useless and dangerous to the people of England". Lands owned by the royal family and the church were sold and the money was used to pay the parliamentary soldiers. People were no longer fined for not attending their local church. However, everyone was still expected to attend some form of religious worship on Sundays. The country was now declared to be a "Commonwealth and Free State" under the rule of Parliament, and the government was entrusted to a Council of State, under the provisional chairmanship of Oliver Cromwell. (7)

Following the English Civil War groups such as the Fifth Monarchists, Levellers, Anabaptists and Diggers began to demand political reforms. (8) Powell was a supporter of the Fifth Monarchists who believed that the death of Charles I in 1649 was a prophetic moment, signalling the coming of the new millennium and the reign of Christ and the saints on earth. This was as a result of their close reading of the prophecies of the Book of Daniel, in which the fall of the four earthly empires (Assyrian, Persian, Greek and Roman) would be followed by the rule of "King Jesus" and his saints. (9)

Clement Walker was a lawyer and a MP, and he feared what had been unleashed during the war. "They have cast all the mysteries and secrets of government... before the vulgar (like pearls before swine), and have taught both the solidarity and people to look so far into them as to ravel back all governments to the first principles of nature... They have made the people thereby so curious and so arrogant that they will never find humility enough to a civil rule." (10)

Oliver Cromwell was opposed to these groups and their leaders such as John Lilburne were imprisoned. Soldiers continued to protest against the government. The most serious rebellion took place in London. Troops commanded by Colonel Edward Whalley were ordered from the capital to Essex. A group of soldiers led by Robert Lockyer, refused to go and barricaded themselves in The Bull Inn near Bishopsgate, a radical meeting place. A large number of troops were sent to the scene and the men were forced to surrender. The commander-in-chief, General Thomas Fairfax, ordered Lockyer to be executed. (11)

Oliver Cromwell and Fifth Monarchists

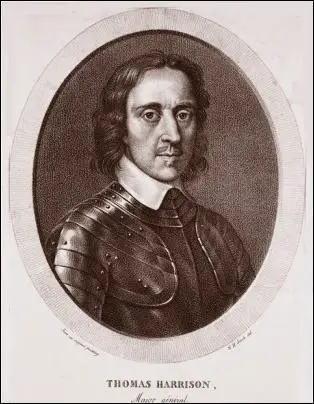

There were senior figures in Cromwell's government that were sympathetic to the Fifth Monarchists. This included Major General Thomas Harrison. According to Edmund Ludlow, a senior officer in the New Model Army, Harrison was a committed Fifth Monarchists and was willing to take up arms to usher in the kingdom of heaven on earth. Harrison used to quote the apocalyptic book of Daniel (7:18) that "the saints… shall take the kingdom", to which he added another to the same effect, "That the kingdom shall not be left to another people"'. (12)

In July, 1653, Oliver Cromwell established the Nominated Assembly and the Parliament of Saints. The total number of nominees was 140 (129 from England, five from Scotland and six from Ireland). Harrison was responsible for nominating four members of his own Fifth Monarchist sect, as well as getting himself elected to the new council of state. (13) The nominated assembly grappled with several of Harrison's favourite issues, including the immediate abolition of tithes. There was general consensus that tithes were objectionable, but no agreement about what mechanism for generating revenue should replace them. (14)

Another leading figure in the Fifth Monarchist movement was John Carew, who represented Devon in the Parliament of Saints. Carew did not object to government by a single person, but soon expressed his hostility to the Cromwellian protectorate and his suspicion regarding its hereditary pretensions in a work called The Grand Catastrophe (January 1654). His opposition to Cromwell was reflected in his rumoured involvement in 1654 in the ‘Wildman' plot with its call to arms against the protector, and in his demand for the release of two Fifth Monarchist preachers, Christopher Feake and John Rogers, in February 1655. (15)

Bernard Capp, the author of The Fifth Monarchy Men (1972) has argued the Fifth Monarchist movement in the 1650s was among cloth workers and other craftsmen. Capp stressed their class consciousness, and their hostility to aristocracy. (16) Christopher Hill has suggested that their programme was in many points similar to that of the Levellers, attacking tithing priests and lawyers as well as the rich. (17)

During this period Christopher Feake emerged as one of the leaders of the movement. He was lecturer at both St Ann Blackfriars and All Hallows-the-Great. In 1652, on the recommendation of Major-General Thomas Harrison, he preached before the House of Commons. In 1654 he was removed from his posts on account of being "obnoxious to the government". It was from these pulpits that his descent into notoriety may be said to have commenced in earnest. (18)

After a meeting with Feake, Powell described Oliver Cromwell as a "vile person" and urged his hearers to ask God whether he would "have Oliver Cromwell or Jesus Christ to reign over us?" He was arrested on 21 December, and was released on the twenty-fourth. He made his way back to Wales on 10 January 1654 and began a programme of preaching in mid-Wales which entrenched his opposition to the new government. "His enemies sent ample evidence of his hostility and customary vehemence of language, but noted also the element of respect he commanded among the magistrates of mid-Wales. By March 1654 he had devised a petition against the government, and he and ten sympathizers were summoned before Montgomery great sessions for this activity against the protectorate. There was no prospect of his joining any alliance with royalists, however, for all his dislike of the new regime. In the spring of 1655 he was again in arms against insurgent royalists, accompanied by men of Wrexham: he was wounded in a skirmish." (19)

Restoration

On the Restoration the two leading Fifth Monarchists, Thomas Harrison and John Carew were obvious targets for the Royalists. Harrison and Carew refused to flee the country and was therefore like other Regicides arrested and brought to the Tower of London. At his trial in October 1660 Harrison asserted that he had acted in the name of the parliament of England and by their authority. "Maybe I might be a little mistaken, but I did it all according to the best of my understanding, desiring to make the revealed will of God in his holy scriptures as a guide to me". (20)

Harrison claimed he had been acting on the authority of the House of Commons: Denzil Holles rejected this argument. "You do very well know that this that you did, this horrid, detestable act which you committed, could never be perfected by you till you had broken the Parliament. That House of Commons, which you say gave you authority, you know what yourself made of it when you pulled out the speaker; therefore do not make the Parliament to be the author of your black crimes." (21)

Harrison was found guilty of treason and was sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. On 13th October 1660 he was taken on a sledge to Charing Cross, the place of his execution. On the way to his execution, Harrison said: "I go to suffer upon the account of the most glorious cause that ever was in the world." (22) Harrison said on the scaffold: "Gentleman, by reason of some scoffing, that I do hear, I judge that some do think I am afraid to die... I tell you no, but it is by reason of much blood I have lost in the wars, and many wounds I have received in my body which caused this shaking and weakness in my nerves." (23)

John Carew was also arrested and at his trial denied being "moved by the devil" and professed obedience to God's "holy and righteous laws" and the authority of an act of parliament. Found guilty, he was executed at Charing Cross on 15 October, although his family was granted his body for private burial rather than having to suffer the ignominy of its public display. Carew went to the scaffold confident that his prosecutors would be destroyed by the wrath of God, and by the "resurrection of this cause". He said that his own blood would "warm the blood that had been shed, and cause notable execution to come down upon the head of their enemy" (24)

Vavasour Powell was arrested and sent to the Fleet prison and wrote there The Bird in the Cage Chirping (1662) an attack on King Charles II: "We have been stomach-full, sick and surfeited with the sweet and fat things of God's house … we trampled and trod under foot the good pastures". (25)

On 30 September 1662 he was moved to Southsea Castle and remained there for five years. The downfall of Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon, seems to have provided a reason for freeing long-term prisoners of conscience like Powell, and in November 1667 the preacher at last walked free. Powell refused to stop criticizing the government and in March 1668 he was reported to have preached to a congregation of Fifth Monarchists at Blue Anchor Alley, Old Lane, London. (26)

Powell was arrested for unlawful preaching and was sent to Fleet Prison in May 1669. He died on 27 October, 1670, of a disease of the alimentary canal involving haemorrhaging.

Primary Sources

(1) Stephen K. Roberts, Vavasour Powell : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (3rd October, 2013)

On 2 February 1642 Powell married Joan Quarrell, widow of a Presteigne merchant and Hereford freeman, Paul Quarrell. In 1642 he appeared at Presteigne great sessions charged with nonconformity, but was found not guilty. He must have left shortly afterwards for London, and was there by August 1642, ahead of the refugees from the Llanfaches congregation of Monmouthshire, the first Independent church in Wales. Once there, he signed articles accusing his persecutors in Radnor of anti-parliamentarian activities. He preached in the parish of St Anne and St Agnes, Aldersgate, and in Crooked Lane, in the City, before moving to Dartford, in Kent, where he was vicar between mid-1643 and January 1646. As his sympathies were with Independent varieties of protestantism, this could only have been a temporary haven. If he had not already met Morgan Llwyd, the Welsh Independent minister and writer, he probably did so in 1644, as the latter sailed that year from Kent as part of the parliamentarian force relieving Pembrokeshire.

In 1646 Powell left Dartford to join the New Model Army forces besieging Oxford, having resigned from his living, but on 11 September he received a certificate of approval from the Westminster assembly as to his fitness for the ministry in Wales and his ability to preach in Welsh. Already, however, Thomas Edwards in Gangraena had noted 'many erroneous things' in his theology and reported Powell's harsh way with his opponents. That Powell could at this point accept presbyterian authority, and that the assembly felt able to endorse him despite the attacks on him in Gangraena, indicate that he was willing to present himself as orthodox. In June 1648 he, Ambrose Mostyn, and Llwyd were awarded maintenance from the tithes of six Montgomeryshire parishes to preach in the north Wales counties, shortly after he had signed a declaration by Montgomeryshire gentry, freeholders, and ministers to adhere to parliament and suppress the revolt which had broken out in May. He attached himself to the army of Thomas Mytton, and was injured at the siege of Beaumaris in October 1648. In the heat of the action he heard a voice telling him that he was chosen to preach the gospel; he later attributed his survival to divine intervention on account of his calling.

(2) Christopher Hill, The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution (1991)

This is the essential background to bear in mind when we consider later attempts to achieve democratic political objectives - the Diggers by quiet infiltration, by contracting in, by appeal to Oliver Cromwell; the Fifth Monarchists, who expected the direct intervention of King Jesus in English politics to bring about the effects which democratic political methods had failed to achieve; the Seekers and Ranters, less directly political, but deeply concerned, as were the Quakers, with the problem of "sin" and how to escape from its all-pervasiveness. What strikes the historian is how many political objectives all these groups have in common - abolition of tithes and a state church, reform of the law, of the educational system, hostility to class distinctions. They differ profoundly in the means they advocated to achieve these common ends as they thrash around in the confining pool of their society, from which, in the last resort, there is no escape.