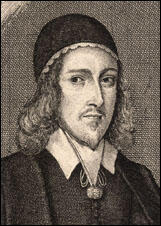

John Rogers

John Rogers, the second of the four children of Nehemiah Rogers and his wife, Margaret, sister of the Essex minister William Collingwood, was born at Messing in 1627. Rogers attended school at Maldon and when he was about ten he had a vision in which he was nearly impelled to cast himself on a sword; this he interpreted as a divine warning, much as he did thunder and lightening. (1) In the ensuing five years he plunged into "the black gulf of despair", lost in a world teeming with devils in bushes and trees. (2)

As Richard L. Greaves has pointed out: " Preoccupied with the howling and screeching of the damned, he despaired of salvation, weeping much of the night and sleeping with his hands clasped in a prayerful posture. His periodic refusal to eat, sobbing, and pulling out of his hair persuaded some observers that he should be confined in Bedlam (Bethlem) Hospital. Experiencing profound alienation and finding no relief in asceticism, he contemplated suicide, but relief came at age fifteen when he learned in a dream that salvation could only be attained through Christ's righteousness." (3)

Rogers graduated from King's College, Cambridge in 1642. During the English Civil War parliamentary forces occupied where he was living and he claims he was driven into abject poverty. He doubted the existence of God and had thoughts of committing suicide. (4) He then received an offer to tutor children of the gentry at Diddington. That night he had a vision of a bearded, white-haired man who told him he had been called to preach. In 1645 he was teaching at a free school in St Neots and preaching at nearby Toseland. (5)

John Rogers - Radical Preacher

In 1648 he was appointed as the rector of Purleigh, one of the wealthier livings in Essex, Rogers hired a curate and moved to London, where he associated with Independents and became hostile to Presbyterians. In an epistle dated 25 March 1653 Rogers accused his parishioners of producing nothing but briars and thorns and of conspiring against him: "The more you were watered, the more you withered", making it impossible to administer the sacraments to them. (6)

In Ohel, or, Beth-shemesh (1653), Rogers articulated millenarian convictions and argued that the execution of King Charles I had been partial fulfillment of the prophecy in Daniel 2: 31–44. "In preparation for Christ's return, Rogers called for a drastic purge of the law, deeming it tyrannical and a vehicle for the ruination of godly families. Denouncing lawyers as knaves, he accused them of oppressing others, living in sin, and impeding the work of reformation. No less acceptable were monarchy and nobility; the latter, he opined, was a fancy for fools and children. He called as well for the abolition of mandatory tithing." (7)

Rogers now became one of the leaders of the Fifth Monarchist movement that believed that the death of the king was a prophetic moment, signalling the coming of the new millennium and the reign of Christ and the saints on earth. This was as a result of their close reading of the prophecies of the Book of Daniel, in which the fall of the four earthly empires (Assyrian, Persian, Greek and Roman) would be followed by the rule of "King Jesus" and his saints. (8)

Oliver Cromwell and Parliament

Oliver Cromwell became increasingly frustrated by the inability of Parliament to get anything done. His biographer, Pauline Gregg, has pointed out: "He realized that all revolutions are about power and he was asking himself who, or what, should exercise that power. He knew, moreover, that whoever or whatever was in control must be strong enough to propel the state in one direction. This he learned from his battle experience. To be successful an army must observe one plan, one directive." (9)

On 20th April 1653, Cromwell sent in his troopers with their muskets and drawn swords into the House of Commons. Harrison himself pulled the Speaker, William Lenthall, out of the Chair and pushed him out of the Chamber. That afternoon Cromwell dissolved the Council of State and replaced it with a committee of thirteen army officers. Harrison was appointed as chairman and in effect the head of the English state. (10)

In July, 1653, Oliver Cromwell established the Nominated Assembly and the Parliament of Saints. The total number of nominees was 140 - 129 from England, five from Scotland and six from Ireland. The nominated assembly grappled with several of Harrison's favourite issues, including the immediate abolition of tithes. There was general consensus that tithes were objectionable, but no agreement about what mechanism for generating revenue should replace them. (11)

The Parliament was closed down by Cromwell in December, 1653. Charles H. Simpkinson has argued that Harrison now believed that "England now lay under a military despotism". (12) This decision was fiercely opposed by Major General Thomas Harrison. Cromwell reacted by depriving him of his military commission, and in February, 1654, he was ordered to retire to Staffordshire. However, he was able to keep the land he had acquired during his period of power. The total value of this land was well over £13,000. (13)

The army decided that Oliver Cromwell should become England's new ruler. Some officers wanted him to become king but he refused and instead took the title Lord Protector of the Commonwealth. However, Cromwell had as much power as kings had in the past. The franchise was restricted to those who possessed the very high property qualification of £200 and by the disqualification of all who had taken part in the English Civil War on the royalist side. (14)

Five days after the dissolution of the Rump Parliament in 1653, Rogers issued a broadside calling on Oliver Cromwell to personally select godly men to govern the Commonwealth through a parliament or sanhedrin of seventy members, or one per county, and, in the interim, a council of twelve. This appears to have been the first printed proposal for a nominated assembly. (15)

This was followed by another pamphlet where he insisted that lawyers must be eradicated as a profession. Legal proceedings must be in English, justice dispensed without charge, courts decentralized, and every person permitted to plead his or her case before judges (elected in each town) and juries. Like other Fifth Monarchists he believed tithes too must be abolished. (16) Fifth Monarchists also called for all judges to be elected. (17)

Cromwell's inauguration as Lord Protector on 16 December 1653 upset Rogers and wrote to him calling for reform and continued to denounce "anti-Christian clergy and tyrannical laws". (18) At a meeting in his church on 28 March 1654, John Rogers denounced the apostasy of eminent people, churches, and ministers, protested the persecution of the godly, and called for a spiritual union of saints. John Thurloe, the head of Cromwell's intelligence services, ordered the seizure of his books and papers on 7 April 1654. (19)

Rogers responded by sending a letter to Cromwell opposing the rule of government by one person. Having been weaned from monarchy, England must be governed by parliaments elected annually or biennially, but with royalists excluded from the franchise. Rogers also renounced the use of weapons to oppose the protectorate and called for the release of Christopher Feake, and other Fifth Monarchists in prison. He also condemned all censorship and the closure of his meeting-place. (20)

John Rogers had strong opinions on sexual equality. This was partly inspired by his wife's interest in the subject. He forbade men to despise women "or wrong them of their liberty of voting and speaking in common affairs. To women I say, I wish you be not too forward (a reference to his wife) and yet not too backward, but hold fast your liberty... Ye ought not by your silence to betray your liberty." (21)

Fifth Monarchist

On 27 July 1654 Rogers was arrested and imprisoned in Lambeth Palace. Along with Christopher Feake and other Fifth Monarchists he supported the publication of A Declaration of Several of the Churches of Christ, calling on parliament to remember the manifestos issued by the army at St Albans and Musselburgh and to repudiate the protector's embrace of the "Antichrist". (22)

In response to letters from members of Rogers's congregation for his release, Cromwell met with him and a dozen of his followers at Whitehall on 6 February 1655. According to an account of the proceedings published as The Faithfull Narrative of the Late Testimony Rogers insisted on a fair trial, castigated the army as apostate for having broken its promises, and insisted that he had not resisted magistrates because he acted in defence of just principles. Cromwell's laws, he asserted, were worse than those of the Pope as well as tyrannical because they made words treasonable. (23)

When Cromwell failed to dissuade him from attacking the government Rogers was returned to Lambeth, despite the efforts of a Fifth Monarchist delegation that included Major General Thomas Harrison to obtain his release. He was transferred to Windsor Castle in late March, to Sandown Castle on the Isle of Wight in early October, and to Arten House on the same island on 31 October, 1655. His wife, despite being pregnant, and their children remained with him; at one point their beds were removed, possibly contributing to the death of his son Peter. (24)

On 5 December 1655 he was transferred to Carisbrooke Castle and confined in what he described as a dungeon, prompting him to compare his plight to that of the martyr Nicholas Ridley. On 11 December 1656 the council ordered Rogers's release. In April 1657 Thomas Venner planned a rising that was backed by a manifesto, a flag that depicted a red lion and the motto "Who shall rouse him up?" The rebels intended to rendezvous at Mile End Green and then march into East Anglia, where they expected many recruits to join them. Venner and about 25 other men were arrested in London before "their plans for a theocracy and government according to biblical lore had been put to much of a test." (25) Rogers, like other leading Fifth Monarchists refused to join the rebellion. (26)

Rogers published A Reviving Word (September 1657) where he called on saints throughout the three kingdoms to unite in preparation for the fifth monarchy. On 3 February 1658 Cromwell ordered the arrest of Rogers, Courtney, and John Portman on charges of sedition, but Rogers was released on 16 April, and in February 1659 a parliamentary committee adjudged this imprisonment a breach of the subjects' liberties. In The Plain Case of the Common-Weal, Rogers warned that "the ship of the Common-wealth hath sprung so many leaks'" that it could sink. Troubled that elections for the third protectorate parliament had resulted in the return of numerous enemies of the Commonwealth, he urged its defenders to unite and called on the army to preserve parliamentary government. (27)

Groups like the Fifth Monarchists and the Levellers grew disillusioned with the dictatorial policies of Oliver Cromwell. In May 1657 Edward Sexby published, under a pseudonym, Killing No Murder, a pamphlet that attempted to justify the assassination of Cromwell. Sexby accused Cromwell of the enslavement of the English people and argued for that reason he deserved to die. After his death "religion would be restored" and "liberty asserted". He hoped "that other laws will have place besides those of the sword, and that justice shall be otherwise defined than the will and pleasure of the strongest". (28) The following month Sexby arrived in England to carry out the deed, however, he was arrested on 24th July. He remained in the Tower of London until his death on 13th January 1658. (29)

In 1658 Oliver Cromwell announced that he wanted his son, Richard Cromwell, to replace him as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth. The English army was unhappy with this decision. While they respected Oliver as a skillful military commander, Richard was just a country farmer. To help him Cromwell brought him onto the Council to familiarize him with affairs of state. (30) Oliver Cromwell died on 3rd September 1658. Richard Cromwell became Lord Protector but he was bullied by conservative MPs into support measures to restrict religious toleration and the army's freedom to indulge in political activity. The army responded by forcing Richard to dissolve Parliament on 21st April, 1659. The following month he agreed to retire from government. (31)

In July 1659 the council of state commissioned Rogers to preach in Ireland, but before he could depart he was reassigned as chaplain to Colonel Charles Fairfax's regiment when it was dispatched to suppress the rebellion led by George Booth. On 13 October the council appointed him preacher at St Julian's, Shrewsbury, with a stipend of £150 p.a., but later that year he returned to Dublin. He was arrested there in January, but on the 27th the council ordered his release. (32)

The Restoration

Parliament and the leaders of the army now began arguing amongst themselves about how England should be ruled. General George Monk, the officer in charge of the English army based in Scotland, decided to take action, and in 1660 he marched his army to London. According to Hyman Fagan: "Faced with a threatened revolt, the upper classes decided to restore the monarchy which, they thought, would bring stability to the country. The army again intervened in politics, but this time it opposed the Commonwealth". (33)

Monck reinstated the House of Lords and the Parliament of 1640. Royalists were now in control of Parliament. Monck now contacted Charles, who was living in Holland. Charles agreed that if he was made king he would pardon all members of the parliamentary army and would continue with the Commonwealth's policy of religious toleration. Charles also accepted that he would share power with Parliament and would not rule as an 'absolute' monarch as his father had tried to do in the 1630s. (34)

Despite this agreement a special court was appointed and in October 1660 those Regicides who were still alive and living in Britain were brought to trial. Ten were found guilty and were sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. This included Thomas Harrison, John Jones, John Carew and Hugh Peters. Others executed included Adrian Scroope, Thomas Scot, Gregory Clement, Francis Hacker, Daniel Axtel and John Cook. On the way to his execution, Harrison said: "I go to suffer upon the account of the most glorious cause that ever was in the world." (35)

Rogers took refuge in the Netherlands where he studied medicine at Leiden University and Utrecht University, graduating MD at the latter in October 1662. The same year the government responded favourably to his petition for permission to return to England, and by the year's end he had settled at Bermondsey where he practised medicine and preached. On 13 June 1664 he was incorporated MD at Oxford. The date of Rogers's death is unknown. Some historians have speculated that he may have died in the plague. (36)

Primary Sources

(1) Richard L. Greaves, John Rogers : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (January, 2008)

Rogers, John (b. 1627), Fifth Monarchist writer, was born at Messing, Essex, the second of the four children of Nehemiah Rogers (bap. 1594, d. 1660) and his wife, Margaret, sister of the Essex minister William Collingwood. Rogers attended school at Malden, Essex, and soon was influenced by William Fenner, whose pulpit oratory frightened him, and Stephen Marshall, who inspired him to take notes and memorize sermons, a practice Rogers continued until about 1655....

Because of Rogers's attraction to puritans, his father, the conformist vicar of Messing, expelled him from the family home in 1642. Rogers's sense of alienation from, and fear of, his father were manifest in recurring dreams in which the latter blamed him for setting his coach-house afire. At Easter 1642 Rogers had matriculated as a sizar at King's College, Cambridge. When parliamentary forces occupied the town he was driven into abject poverty, eating grass, leather, fish skins, and old quills, some of which he found in dung-heaps. Desperate, he tried to eat his own fingers, stopping only because of the pain. Necromancy and magic provided no relief, and he sought solace in composing religious meditations and reading sermons on Lazarus and Dives, a favourite theme of the indigent. In utter despair, he was about to commit suicide when he received an offer to tutor children of the gentry at Diddington, Huntingdonshire. That night he had a vision of a bearded, white-haired man who told him he had been called to preach. He was soon teaching at a free school in St Neots, Huntingdonshire, and preaching at nearby Toseland about 1645–6.

(2) Pauline Gregg, Oliver Cromwell (1988)

There is evidence throughout his career that the toleration of which Cromwell spoke in his dispatches was something real and urgent to him. He showed it in recruiting his army and in retaining good soldiers whose religious convictions were not quite in accord with his own. He showed it in his attitude to the Fifth Monarchy Men who were a perpetual goading irritant. He talked with the preachers John Simpson and Christopher Feake. He dealt gently with the rough and earnest Harrison, he stepped between Nayler and the angry Parliament. He received John Rogers, another exuberant Fifth Monarchy preacher, with a group of his followers at Whitehall. When his disciples complained that Rogers was being persecuted for conscience' sake Cromwell was moved to cry out that he suffered as a railer, a seducer, and a stirrer up of sedition. "God is my witness", he exclaimed, "no man in England doth suffer for the testimony of Jesus".