On this day on 28th June

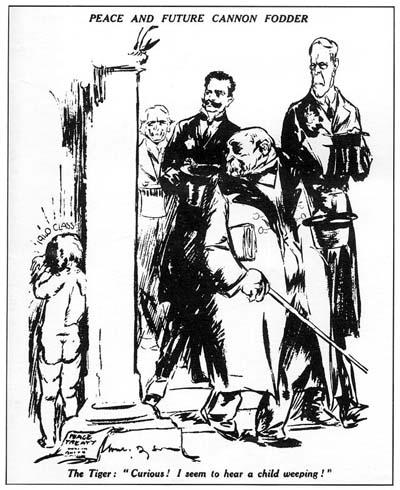

On this day in 1919 the Treaty of Versailles is signed. When the Armistice was signed on 11th November, 1918, it was agreed that there would be a Peace Conference held in Paris to discuss the post-war world. Opened on 12th January 1919, meetings were held at various locations in and around Paris until 20th January, 1920.

Leaders of 32 states representing about 75% of the world's population, attended. However, negotiations were dominated by the five major powers responsible for defeating the Central Powers: the United States, Britain, France, Italy and Japan. Important figures in these negotiations included Georges Clemenceau (France) David Lloyd George (Britain), Vittorio Orlando (Italy), and Woodrow Wilson (United States).

Wilson wanted to the peace to be based on the Fourteen Points published in October 1918. Lloyd George was totally opposed to several of the points. This included Point II "Absolute freedom of navigation upon the seas, outside territorial waters, alike in peace and in war, except as the seas may be closed in whole or in part by international action for the enforcement of international covenants." Lloyd George saw this as undermining the country's ability to protect the British Empire.

Another issue that worried Lloyd George was Point III: "The removal, so far as possible, of all economic barriers and the establishment of an equality of trade conditions among all the nations consenting to the peace and associating themselves for its maintenance." His government was split on the subject. Some favoured a system where tariffs were placed on countries outside the British Empire. Lloyd George would also have difficulty in delivering Point IV. "Adequate guarantees given and taken that national armaments will be reduced to the lowest point consistent with domestic safety."

Seven of Wilson's points demanded or implied support for "autonomous development" or "self-determination". For example, Point V: "A free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims, based upon a strict observance of the principle that in determining all such questions of sovereignty the interests of the populations concerned must have equal weight with the equitable claims of the Government whose title is to be determined." This was an attempt to undermine the British Empire.

These measures were also opposed by Georges Clemenceau. He told Lloyd George that if he accepted what Wilson proposed, he would have serious problems when he returned to France. "After the millions who have died and the millions who have suffered, I believe - indeed I hope - that my successor in office would take me by the nape of the neck and have me shot."

While the discussions were taking place, the Allies continued the naval blockade of Germany. It is estimated that by December, 1918, there were 763,000 civilian famine related deaths. Robert Smillie, the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB), in June, 1919, issued a statement condemning the blockade claiming that another 100,000 German civilians had died since the armistice.

David Lloyd George admitted that the blockade was killing German civilians and was fermenting revolution, but thought it necessary in order to force Germany to sign the peace treaties: "The mortality among women, children and the sick is most grave and sickness, due to hunger, is spreading. The attitude of the population is becoming one of despair and people feel that an end by bullets is preferable to death by starvation."

Ulrich Brockdorff-Rantzau, the leader of the German delegation, made a speech attacking the blockade. "Crimes in war may not be excusable, but they are committed in the struggle for victory in the heat of passion which blunts the conscience of nations. The hundreds of thousands of non-combatants who have perished since November 11 through the blockade were killed with cold deliberation after victory had been won and assured to our adversaries."

Clemenceau and Lloyd George both hated each other. Clemenceau believed that Lloyd George knew nothing about the world beyond Great Britain, lacked a formal education and "was not an English gentleman". Lloyd George thought Clemenceau a "disagreeable and bad-tempered old savage" who, despite his large head, "had no dome of benevolence, reverence or kindliness".

Raymond Poincare, another French politician, commented that Lloyd George told Clemenceau: "I won't budge, I will act like a hedgehog and wait until they come to talk to me. I will yield nothing. We will see if they can manage without me." Poincare believed that "Lloyd George is a trickster... I don't like being double-crossed. Lloyd George has deceived me. He made me the finest promises, and now he breaks them. Fortunately, I think that at the moment we can count on American support."

Lloyd George told Edward House, a member of the USA's delegation to the Paris Peace Conference, that "he had to have a plausible reason for having fooled the British people about the questions of war costs, reparations and what not... Germany could not pay anything like the indemnity which the French demanded."

David Lloyd George put in a claim for £25 billion of reparations at the rate of £1.2 billion a year. Clemenceau wanted £44 billion, whereas Wilson said that all Germany could afford was £6 billion. On 20th March 1919, Lloyd George explained to Wilson that it would be difficult to "disperse the illusions which reign in the public mind". He had of course been partly responsible for this viewpoint. He was especially worried about having to "face up" to the "400 Members of Parliament who have sworn to exact the last farthing of what is owing to us."

Lloyd George argued that Germany should pay the costs of widows' and disability pensions, and compensation for family separations. John Maynard Keynes, an economist who was the chief Treasury representative of the British delegation, was totally opposed to the idea. He argued that if reparations were set at a crippling level the banking system, certainly of Europe and probably of the world, would be in danger of collapse. Lloyd George replied: "Logic! Logic! I don't care a damn for logic. I am going to include pensions."

Philip Kerr, 11th Marquess of Lothian, also advised Lloyd George against demanding too much from Germany: "You may strip Germany of her colonies, reduce her armaments to a mere police force and her navy to that of a third rate power, all the same if she feels that she has been unjustly treated in the peace of 1919, she will find means of exacting retribution from her conquerors... The greatest danger that I see in the present situation is that Germany may throw in her lot with Bolshevism and place her resources, her brains, her vast organising powers at the disposal of the revolutionary fanatics whose dream is to conquer the world for Bolshevism by force of arms."

When it was rumoured that Lloyd George was willing to do a deal closer to the £6 billion than the sum proposed by the French, The Daily Mail began a campaign against the Prime Minister. This included publishing a letter signed by 380 Conservative backbenchers demanding that Germany pay the full cost of the war. "Our constituents have always expected and still expect that the first edition of the peace delegation would be, as repeatedly stated in your election pledges, to present the bill in full, to make Germany acknowledge the debt and then discuss ways and means of obtaining payment. Although we have the utmost confidence in your intentions to fulfil your pledges to the country, may we, as we have to meet innumerable inquiries from our constituents, have your renewed assurances that you have in no way departed from your original intention."

Lloyd George made a speech in the House of Commons where he argued that it was wrong to suggest that he was willing to accept a lower figure. He ended his speech with an attack on Lord Northcliffe, who he accused of seeking revenge for his exclusion from the government. "Under these conditions I am prepared to make allowance, but let me say that when that kind of diseased vanity is carried to the point of sowing dissension between great allies whose unity is essential to the peace of the world... then I say, not even that kind of disease is a justification for so black a crime against humanity."

Negotiations continued in Paris over the level of reparations. The Australian prime minister, William Hughes, joined the French in claiming the whole cost of the war, his argument being that the tax burden imposed on the Allies by the German aggression should be regarded as damage to civilians. He estimated the cost of this was £25 billion. John Foster Dulles, commented that in his opinion, Germany should only pay about £5 billion. Faced with the possibility of an American veto, the French abandoned their claims to war costs, being impressed by Dulles's argument that, having suffered the most damage, they would get the largest share of reparations.

David Lloyd George eventually agreed that he been wrong to demand such a large figure and told Dulles he "would have to tell our people the facts". John Maynard Keynes suggested to Edwin Montagu that whereas Germany should be required to "render payment for the injury she has caused up to the limit of her capacity" but it was "impossible at the present time to determine what her capacity was, so that the fixing of a definite liability should be postponed."

Keynes explained to Jan Smuts that he believed the Allies should take a new approach to negotiations: "This afternoon... Keynes came to see me and I described to him the pitiful plight of Central Europe. And he (who is conversant with the finance of the matter) confessed to me his doubt whether anything could really be done. Those pitiful people have little credit left, and instead of getting indemnities from them, we may have to advance them money to live."

On 28th March, 1919, Keynes warned Lloyd George about the possible long-term economic problems of reparations. "I do not believe that any of these tributes will continue to be paid, at the best, for more than a very few years. They do not square with human nature or march with the spirit of the age." He also thought any attempt to collect all the debts arising from the First World War would poison, and perhaps destroy, the capitalist system.

Georges Clemenceau made his final appeal to persuade the delegates to impose harsh terms on the Germans. "For many years the rulers of Germany, true to the Prussian tradition, strove for a position of dominance in Europe. They were not satisfied with that growing prosperity and influence to which Germany was entitled, and which all other nations were willing to accord her, in the society of free and equal peoples. They required that they should be able to dictate and tyrannise to a subservient Europe, as they dictated and tyrannised over a subservient Germany... The conduct of Germany is almost unexampled in human history. The terrible responsibility which lies at her doors can be seen in the fact that not less than seven million dead lie buried in Europe, while more than twenty million others carry upon them the evidence of wounds and sufferings, because Germany saw fit to gratify her lust for tyranny by resort to war."

Clemenceau then went on to argue: "Justice, therefore, is the only possible basis for the settlement of the accounts of this terrible war. Justice is what the German Delegation asks for and says that Germany had been promised. Justice is what Germany shall have. But it must be justice for all. There must be justice for the dead and wounded and for those who have been orphaned and bereaved that Europe might be freed from Prussian despotism. There must be justice for the peoples who now stagger under war debts which exceed £30,000,000,000 that liberty might be saved. There must be justice for those millions whose homes and land, ships and property German savagery has spoliated and destroyed. That is why the Allied and Associated Powers have insisted as a cardinal feature of the Treaty that Germany must undertake to make reparation to the very uttermost of her power; for reparation for wrongs inflicted is of the essence of justice."

Keynes argued that it was in the best interest of the future of capitalism and democracy for the Allies to deal swiftly with the food shortages in Germany: "A proposal which unfolds future prospects and shows the peoples of Europe a road by which food and employment and orderly existence can once again come their way, will be a more powerful weapon than any other for the preservation from the dangers of Bolshevism of that order of human society which we believe to be the best starting point for future improvement and greater well-being."

Eventually it was agreed that Germany should pay reparations of £6.6 billion (269bn gold marks). Keynes was appalled and considered that the figure should be below £3 billion. He wrote to Duncan Grant: "I've been utterly worn out, partly by incessant work and partly by depression at the evil round me... The Peace is outrageous and impossible and can bring nothing but misfortune... Certainly if I were in the Germans' place I'd die rather than sign such a Peace... If they do sign, that will really be the worst thing that could happen, as they can't possibility keep some of the terms, and general disorder and unrest will result everywhere. Meanwhile there is no food or employment anywhere, and the French and Italians are pouring munitions into Central Europe to arm everyone against everyone else... Anarchy and Revolution is the best thing that can happen, and the sooner the better."

The Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28th June 1919. Keynes wrote to Lloyd George explaining why he was resigning: "I can do no more good here. I've on hoping even though these last dreadful weeks that you'd find some way to make of the Treaty a just and expedient document. But now it's apparently too late. The battle is lost. I leave the twins to gloat over the devastation of Europe, and to assess to taste what remains for the British taxpayer."

Eventually five treaties emerged from the Conference that dealt with the defeated powers. The five treaties were named after the Paris suburbs of Versailles (Germany), St Germain (Austria), Trianon (Hungary), Neuilly (Bulgaria) and Serves (Turkey). These treaties imposed territorial losses, financial liabilities and military restrictions on all members of the Central Powers.

On this day in 1914 Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Duchess Sophie von Chotkova are assassinated. Just before 10 o'clock on Sunday, 28th June, 1914, they arrived in Sarajevo by train. General Oskar Potiorek, Governor of the Austrian provinces of Bosnia-Herzegovina, was waiting to take the royal party to the City Hall for the official reception.

In the front car was Fehim Curcic, the Mayor of Sarajevo and Dr. Gerde, the city's Commissioner of Police. Franz Ferdinand and Duchess Sophie were in the second car with Oskar Potiorek and Count von Harrach. The car's top was rolled back in order to allow the crowds a good view of its occupants.

At 10.10, when the six car possession passed the central police station, Nedjelko Cabrinovic hurled a hand grenade station at the archduke's car. The driver accelerated when he saw the object flying towards him and the grenade exploded under the wheel of the next car. Two of the occupants, Eric von Merizzi and Count Boos-Waldeck were seriously wounded. About a dozen spectators were also hit by bomb splinters.

Franz Ferdinand's driver, Franz Urban, drove on extremely fast and other members of the Black Hand group on the route, Cvijetko Popovic, Gavrilo Princip, Danilo Ilic and Trifko Grabez, were unable to fire their guns or hurl their bombs at the Archduke's car.

After attending the official reception at the City Hall, Franz Ferdinand asked about the members of his party that had been wounded by the bomb. When the archduke was told they were badly injured in hospital, he insisted on being taken to see them. A member of the archduke's staff, Baron Morsey, suggested this might be dangerous, but Oskar Potiorek, who was responsible for the safety of the royal party, replied, "Do you think Sarajevo is full of assassins?" However, Potiorek did accept it would be better if Duchess Sophie remained behind in the City Hall. When Baron Morsey told Sophie about the revised plans, she refused to stay arguing: "As long as the Archduke shows himself in public today I will not leave him."

In order to avoid the city centre, General Oskar Potiorek decided that the royal car should travel straight along the Appel Quay to the Sarajevo Hospital. However, Potiorek forgot to tell the driver, Franz Urban, about this decision. On the way to the hospital, Urban took a right turn into Franz Joseph Street. One of the conspirators, Gavrilo Princip, was standing on the corner at the time. Oskar Potiorek immediately realised the driver had taken the wrong route and shouted "What is this? This is the wrong way! We're supposed to take the Appel Quay!".

The driver put his foot on the brake, and began to back up. In doing so he moved slowly past the waiting Gavrilo Princip. The assassin stepped forward, drew his gun, and at a distance of about five feet, fired several times into the car. Franz Ferdinand was hit in the neck and Sophie von Chotkova i n the abdomen. Princip's bullet had pierced the archduke's jugular vein but before losing consciousness, he pleaded "Sophie dear! Sophie dear! Don't die! Stay alive for our children!" Franz Urban drove the royal couple to Konak, the governor's residence, but although both were still alive when they arrived, they died from their wounds soon afterwards.

at Sarajevo on 28th June, 1914.

On this day in 1915 Vera Brittain, letter to Roland Leighton on being a VAD nurse. "I can honestly say I love nursing, even after only two days. It is surprising how things that would be horrid or dull if one had to do them at home quite cease to be so when one is in hospital. Even dusting a ward is an inspiration. It does not make me half so tired as I thought it would either... The majority of cases are those of people who have got rheumatism resulting from wounds. Very few come straight from the trenches, it is too far, but go to another hospital first. One man in my ward had six operations before coming and is still almost helpless. I have various things to do, all of which belong to the kind of work which is called probationers' work. Another nurse & I have three wards to look after between us. Generally I do two & she does one, as she has other work like massage to do which does not come within my sphere. I have to take the men their breakfasts (they are nearly all in bed for breakfast), prepare the tables for the doctor, with hot water etc, tidy up & dust the wards & make the beds. These latter are not made in the ordinary way but in a particular method you have to learn how to do, & are called medical beds. Not every sick person has a medical bed, but cases of rheumatism always do."