On this day on 21st August

On this day in 1831 Nat Turner leads black slaves and free blacks in a rebellion in Southampton County, Virginia. Turner and about seven other slaves killed Joseph Travis and his family to launch his rebellion. "It was then observed that I must spill the first blood. On which, armed with a hatchet, and accompanied by Will, I entered my master's chamber, it being dark, I could not give a death blow, the hatchet glanced from his head, he sprang from the bed and called his wife, it was his last word, Will laid him dead, with a blow of his axe, and Mrs. Travis shared the same fate, as she lay in bed. The murder of this family, five in number, was the work of a moment, not one of them awoke; there was a little infant sleeping in a cradle, that was forgotten, until we had left the house and gone some distance, when Henry and Will returned and killed it; we got here, four guns that would shoot, and several old muskets, with a pound or two of powder." About 50 white people were killed during the Nat Turner Rebellion.

Turner had hoped this his action would cause a massive slave uprising but only 75 joined his rebellion. Over 3,000 members of the state militia were sent to deal with Turner's rebellion, and they were soon defeated. In retaliation, more than a hundred innocent slaves were killed. Turner went into hiding but was captured six weeks later.

Nat Turner was executed on 11th November, 1831. His actions were defended by Henry H. Garnet: "The patriotic Nathaniel Turner was goaded to desperation by wrong and injustice. By Despotism, his name has been recorded on the list of infamy, but future generations will number him upon the noble and brave."

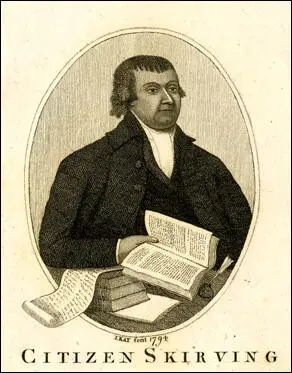

On this day in 1844 one of the sons of William Skirving made a speech on the Scottish Martyrs. "In 1793 I was a young man, indeed a boy, but I have a vivid recollection of those who distinguished themselves in the cause of reform. And it has often struck me, in taking a view of the characters of the leaders of that movement, that on no occasion was there ever such a number of men eminent alike for their moral and religious worth, united for the attainment of a popular right, all of them, with few exceptions, being men who enjoyed the confidence of their fellow citizens, being selected by them to manage their affairs both of a religious and civil description."

William Skirving, was the son of a prosperous farmer from Midlothian. After being educated at Edinburgh University, he became a tutor to the family of Sir Alexander Dick of Prestonville. This was followed by a period farming at Strathruddie. In 1792 his book on farming, The Husbandman's Assistant, was published.

Skirving married and his wife had eight children. In the 1790s Skirving developed radical political views and in the winter of 1792 became secretary of the recently formed, Scottish Association of the Friends of the People. One of his sons commented: "And it has often struck me, in taking a view of the characters of the leaders of that movement, that on no occasion was there ever such a number of men eminent alike for their moral and religious worth, united for the attainment of a popular right, all of them, with few exceptions, being men who enjoyed the confidence of their fellow citizens, being selected by them to manage their affairs both of a religious and civil description." Between October and December, 1793, Skirving helped to organize a series of meetings in Edinburgh. Government spies also attended these meetings and on 2nd December 1793, Skirving, John Gerrald and Maurice Margarot were arrested at a meeting in Edinburgh.

At his trial Skirving was accused of being a member of the Friends of the People, an organisation formed by Charles Grey and a group of Radical Whigs in London. He was also accused of distributing political pamphlets written and published by Thomas Fyshe Palmer and imitating the "proceedings of the French convention" by calling other members "by the name of citizen".

Skirving was also charged with sedition. To help the jury make their decision, the judge, Lord Braxfield, defined sedition as "violating the peace and order of society". When the jury announced that they found Skirving guilty of the charges, Braxfield pronounced the sentence, "that the said William Skirving, be transported beyond the seas for the space of fourteen years." Skirving commented: "Conscious of innocence, my lords, and that I am not guilty of the crimes laid to my charge, this sentence can only affect me as the sentence of man. It is long since I laid aside the fear of man as my rule. I know that what has been done these two days will be rejudged. That is my comfort, and all my hope."

In February 1793, Skirving and three other men arrested in Scotland and found guilty of writing and publishing pamphlets on parliamentary reform, Thomas Muir, John Fyshe Palmer and Maurice Margarot, were placed on prison Hulks on the Thames in preparation for their journey to Australia.

Radicals in the House of Commons immediately began a campaign to save the men now being described as the Scottish Martyrs. On 24th February, 1793, Richard Sheridan presented a petition to Parliament that described the men's treatment as "illegal, unjust, oppressive and unconstitutional". Charles Fox pointed out in the debate that followed that Palmer had done "no more than what had done by William Pitt and the Duke of Richmond" when they campaigned for parliamentary reform.

Attempts to stop the men being transported failed and on 2nd May 1794, The Surprise left Portsmouth and began its 13,000 mile journey to Botany Bay. While the ship was at sea, a group of convicts, including Skirving and Joseph Fyshe Palmer were accused of being involved in a plot to kill the captain and crew. These charges were dropped when the men arrived in Australia.

As a political prisoner Skirving enjoyed more freedom than other convicts and was allowed to buy a small farm in Sydney. Conditions were very harsh in Australia and on 10th March Joseph Gerrald died of tuberculosis. Nine days later, William Skirving, became the second Scottish Martyr to die when he succumbed to dysentery.

In 1845 Thomas Hume, the Radical MP organised the building of a 90 feet high monument in Waterloo Place, Edinburgh. It contained the following inscription: "To the memory of Thomas Muir, Thomas Fyshe Palmer, William Skirving, Maurice Margarot and Joseph Gerrald. Erected by the Friends of Parliamentary Reform in England and Scotland." On the other side of the obelisk, based on the model of Cleopatra's Needle in London, is a quotation from a speech made by Muir on 30th August, 1793: "I have devoted myself to the cause of the people. It is a good cause - it shall ultimately prevail - it shall finally triumph."

On this day in 1858 Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas debate at Ottawa, Illinois. It was described by the journalist, Henry Villard.

The first joint debate between Douglas and Lincoln, which I attended, took place on the afternoon of August 21, 1858, at Ottawa, Illinois. It was the great event of the day, and attracted an immense concourse of people from all parts of the State.

Senator Douglas was very small, not over four and a half feet height, and there was a noticeable disproportion between the long trunk of his body and his short legs. His chest was broad and indicated great strength of lungs. It took but a glance at his face and head to convince one that they belonged to no ordinary man. No beard hid any part of his remarkable, swarthy features. His mouth, nose, and chin were all large and clearly expressive of much boldness and power of will. The broad, high forehead proclaimed itself the shield of a great brain. The head, covered with an abundance of flowing black hair just beginning to show a tinge of grey, impressed one with its massiveness and leonine expression. His brows were shaggy, his eyes a brilliant black.

Douglas spoke first for an hour, followed by Lincoln for an hour and a half; upon which the former closed in another half hour. The Democratic spokesman commanded a strong, sonorous voice, a rapid, vigorous utterance, a telling play of countenance, impressive gestures, and all the other arts of the practiced speaker.

As far as all external conditions were concerned, there was nothing in favour of Lincoln. He had a lean, lank, indescribably gawky figure, an odd-featured, wrinkled, inexpressive, and altogether uncomely face. He used singularly awkward, almost absurd, up-and-down and sidewise movements of his body to give emphasis to his arguments. His voice was naturally good, but he frequently raised it to an unnatural pitch.

Yet the unprejudiced mind felt at once that, while there was on the one side a skillful dialectician and debater arguing a wrong and weak cause, there was on the other a thoroughly earnest and truthful man, inspired by sound convictions in consonance with the true spirit of American institutions. There was nothing in all Douglas's powerful effort that appealed to the higher instincts of human nature, while Lincoln always touched sympathetic cords. Lincoln's speech excited and sustained the enthusiasm of his audience to the end.

On this day in 1872 Aubrey Beardsley, the son of Vincent Beardsley (1840-1909) and his wife, Ellen Agnus (1846–1932), was born at 12 Buckingham Road, Brighton. His father had inherited a fortune, but soon after his son was born he lost it.

As his biographer, Alan Crawford, has pointed out: "He found a job in London but was unconvincing as a breadwinner, and the Beardsleys lived in lodgings for the next twenty years, fending off poverty. His mother never forgave this fall from grace. She hugged her two children to her, cultivated their genteel talents in music and literature, and presented herself as the victim of a mésalliance."

Beardsley was not a strong boy and his mother described him as being "like a delicate little piece of Dresden China". At the age of seven Beardsley was found to have tuberculosis. In 1884 he went to Brighton Grammar School, where his fees were paid for by a great-aunt. His academic career was fairly undistinguished and he left school at sixteen and obtained a job as a clerk in London.

In 1890 Beardsley discovered the work of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and this inspired him to start drawing and painting. He was also impressed with Edward Burne-Jones and as he lived in nearby Rottingdean, he visited him at his home. Burne-Jones praised his work and said he ought to go to art school. Richard Ellmann has argued: "Burne-Jones, usually non-committal when shown work by young artists, offered Beardsley every encouragement." With the support of Burne-Jones, he attended Westminster School of Art in the evenings, where he was taught by Frederick Brown. He was invited to the New English Art Club, an organisation that had been founded by Brown, Henry Tonks and Philip Wilson Steer in 1886.

On 12th July, 1891, Beardsley and his sister Mabel met Oscar Wilde at Edward Burne-Jones' house. Wilde later recorded that Beardsley had a face "like a silver hatchet". The Wildes took Aubrey and Mabel home in their carriage and became friends. It has been argued by one art critic that it was "under Wilde's influence that Beardsley's style became more satrical and sinister". Wilde later claimed that he had "created" Beardsley.

Frank Harris met Beardsley during this period: "The most startling appearance in these early nineties was certainly Aubrey Beardsley. I know no one in the whole history of art who made such an impression, took up such an independent and peculiar place so early in life. Beardsley was of pleasant manners and intercourse: his appearance, too, was interesting; a little above average height, but very slight; perfectly self-possessed, though strangely youthful; quite unaffected, but curiously derisive of affectation in others. While still in his teens he used to sneer at Oscar Wilde's poses to his face, though believing to a certain extent in his genius. Of course Oscar was fifteen years his senior and was better read and had already won a high place."

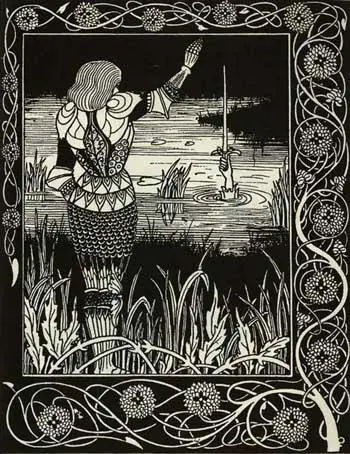

Alan Crawford has pointed out: "By the spring of 1892 he had begun to draw in the linear style which would make him famous, though nothing was published at this stage. He would sketch a design in pencil and then work over it in black ink, producing images of the strongest contrast: black, white, and no greys. He seems to have grasped the potential of the new process blocks, which were replacing wood-engravings at this time as a medium for reproducing images alongside letterpress. Process blocks were made, not of wood, but of metal, on to which the image was transferred photographically. Being stronger than woodblocks, they could sustain finer lines without breaking down in the printing press. The thin, isolated black lines which sweep so voluptuously across the white in some of Beardsley's most famous drawings are a tribute to the process block, which no other illustrator of the 1890s exploited quite so tellingly."

In the autumn of 1892 the publisher Joseph Malaby Dent asked Beardsley to illustrate Morte d'Arthur by Thomas Malory. Beardsley resigned from his job and worked on the book full-time. He was also commissioned to produce eighty drawings for a series of eighteenth-century anthologies.

In 1892 Oscar Wilde wrote a play entitled Salomé. It was performed in Paris but when Wilde attempted to get it produced in London with Sarah Bernhardt taking the star role it was banned by the Lord Chamberlain as being blasphemous. It was published in book form and the Pall Mall Budget asked Beardsley for a drawing to illustrate the review. The editor rejected the drawing as being obscene. However, in April, 1893, it appeared in the first number of The Studio magazine. Wilde liked the drawing, and his publisher, John Lane, the founder of The Bodley Head, suggested that Beardsley do an illustrated edition of the play.

Wilde and Lane were both very pleased with the illustrations Beardsley produced. Wilde's biographer, Richard Ellmann has argued: "The young man (Beardsley) was strange, cruel, disobedient. He was making his way from a Japanese style towards and eighteenth English one. Wilde had expected a Byzantine style like Gustave Moreau's. Instead Beardsley combined jocular impressions of Wilde's face, as in the moon or in the face of Herod, with sinister, sensual overtones." Wilde described the drawings as "quite wonderful". However, he could not resist making a joke about his influences: "Aubrey is almost too Parisian, he cannot forget that he has been to Dieppe - once."

In October 1893 a dispute broke out between Beardsley, Oscar Wilde, Alfred Douglas and John Lane over the French translation of Salomé. Wilde's biographer, Richard Ellmann, has argued: "Beardsley read the translation and said it would not do; he offered to make one of his own. Wilde, fortunately for Douglas, did not like this either. There ensued an acrimonious fourway controversy among Lane, Wilde, Douglas, and Beardsley. Lane said that Douglas had shown disrespect for Wilde, but backed down when Douglas accused him of stirring up trouble between them. Beardsley declared that it would be dishonest to put Douglas's name on the title page, when the translation had been so much altered by Wilde."

Beardsley wrote to his friend, the art critic, Robert Ross: "I suppose you've heard all about the Salomé row. I can tell you I had a warm time of it between Lane and Oscar and company. For one week the numbers of telegraph and messenger boys who came to the door was simply scandalous. I really don't quite know how matters really stand now... The book will be out soon after Xmas. I have withdrawn three of the illustrations and supplied their places with three new ones (simply beautiful and quite irrelevant."

Beardsley used the income from the book illustrations to lease a four-storey house at 114 Cambridge Street, Pimlico. His mother and his sister, Mabel Beardsley, also lived in the house. They held regular gatherings on Thursday afternoons and one of their visitors, Max Beerbohm, remarked on the beauty and charm of his sister.

In February 1894 the illustrated Salomé appeared and created a terrible scandal. The Art Journal commented the effect of Beardsley's drawings was "terrible in its weirdness and suggestions of horror and wickedness". Others complained that most of the seventeen illustrations had nothing to do with the text of the play.

John Lane, was pleased with the success of the book and invited Beardsley and his friend, Henry Harland, to produce a new quarterly, called The Yellow Book. The first edition was published in April, 1894. The reviewer in The Times, pointing to the cover that had been produced by Beardsley, wrote of its "repulsiveness and insolence". The drawings by Beardsley created a great deal of controversy and because of this, the first edition of 5000 copies sold out in five days.

Beardsley became the art editor of the quarterly and managed to persuade William Rothenstein, Charles Conder, John Singer Sargent, Philip Wilson Steer, Frederic Leighton and Walter Sickert to contribute material for the journal. Harland also commissioned H. G. Wells, William Butler Yeats, Arnold Bennett, Max Beerbohm, George Gissing, Henry James, Edmund Gosse and Arthur Symons for the new venture.

Beardsley developed a reputation of someone who liked the high life. One of his friends, William Rothenstein, pointed out: "His work done, Aubrey loved to get into evening clothes and drive into the town". According to Alan Crawford: "In a sense, Beardsley's public persona was as much a work of art as his drawings. He cultivated a dandified appearance before the world, and liked to appear wicked, witty, and decadent like the French. He let his reddish hair fall in a fringe so that he looked half like a boy, and dressed his poor thin body immaculately, as if he expected not to be touched by life - a grey suit, grey gloves, a golden tie, a tasselled cane.... He could be found with his friends, Rothenstein, the caricaturist Max Beerbohm, and the writers Ernest Dowson and Arthur Symons, in the Domino Room of the Café Royal in Regent Street, or among the prostitutes and their gentlemen friends in the St James's Restaurant in Piccadilly Circus, dipping into low life."

The 9th Marquess of Queensberry, the father of Alfred Douglas, discovered details of his son's sexual relationship with Oscar Wilde and planned to disrupt the opening night of The Importance of Being Earnest, at the St James's Theatre on 14th February, 1895, by throwing a bouquet of rotten vegetables at the playwright when he took his bow at the end of the show. Wilde learned of the plan and arranged for policemen to bar his entrance. Two weeks later, Queensberry left his card at Wilde's club, the Albemarle, accusing him of being a "sodomite". Wilde, Douglas and Robert Ross approached solicitor Charles Octavius Humphreys with the intention of suing Queensberry for criminal libel. Humphreys asked Wilde directly whether there was any truth to Queensberry's allegations of homosexual activity between Wilde and Douglas. Wilde claimed he was innocent of the charge and Humphreys applied for a warrant for Queensberry's arrest.

Queensberry entered a plea of justification on 30th March. Owen Dudley Edwards has pointed out: "Having belatedly assembled evidence found for Queensberry by very recent recruits, it declared Wilde to have committed a number of sexual acts with male persons at dates and places named. None was evidence of sodomy, nor was Wilde ever charged with it. Queensberry's trial at the central criminal court, Old Bailey, on 3–5 April before Mr Justice Richard Henn Collins ended in Wilde's attempt to withdraw the prosecution after Queensberry's counsel, Edward Carson QC MP, sustained brilliant repartee from Wilde in the witness-box on questions about immorality in his works and then crushed Wilde with questions on his relations to male youths whose lower-class background was much stressed."

Queensberry was found not guilty and his solicitors sent its evidence to the public prosecutor. Oscar Wilde was arrested on 5th April and taken to Holloway Prison. The following day, Alfred Taylor, the owner of a male brothel Wilde had used, was also arrested. Taylor refused to give evidence against Wilde and both men were charged with offences under the Criminal Law Amendment Act (1885).

The trial of Wilde and Taylor began before Justice Arthur Charles on 26th April. Of the ten alleged sexual partners Queensberry's plea had named, five were omitted from the Wilde indictment. The trial under Charles ended in jury disagreement after four hours. The second trial, under Justice Alfred Wills, began on 22nd May. Douglas was not called to give evidence at either trial, but his letters to Wilde were entered into evidence, as was his poem, Two Loves. Called on to explain its concluding line - "I am the love that dares not speak its name" Wilde answered that it meant the "affection of an elder for a younger man".

Both men were found guilty and sentenced to two years' penal servitude with hard labour. The two known persons with whom Wilde was found guilty of gross indecency were male prostitutes, Wood and Parker. Wilde was also found guilty on two counts charging gross indecency with a person unknown on two separate occasions in the Savoy Hotel. These may in fact have related to acts committed by Douglas, who had also been Wood's lover.

During the trial reference was made to Wilde carrying a book with a yellow cover. The press falsely reported that this was a copy of The Yellow Book. Hostility against Wilde was so great that a crowd threw stones through the windows of the Bodley Head office in Vigo Street. On 8th May a group of contributors approached John Lane and demanded that Beardsley be dismissed as art editor of the journal because. Beardsley was not a homosexual, but he was closely associated with Wilde, and Lane, fearing a decline in the sales of the journal, he was sacked from his post. Beardsley lost his main source of income and had to move to a cheaper house at 57 Chester Row, Pimlico.

Leonard Smithers, was a thirty-four-year-old ex-solicitor who sold old books, prints, and pornography from a shop in Arundel Street, off the Strand. He had also published the highly controversial Book of One Thousand and One Nights by Richard Burton and a series of pornographic books under the imprint of the Erotika Biblion Society. Smithers suggested he was willing to employ Beardsley to produce a rival publication to The Yellow Book. Another rich friend, Marc-André Raffalovich, a well-known homosexual, also volunteered to help fund the journal. The first edition of The Savoy appeared in January 1896. At the party to celebrate the launch of the journal, Beardsley suffered a slight haemorrhage, highlighting that his tuberculosis had not gone away.

Beardsley also began work on the illustrations for The Rape of the Lock, a long narrative poem by Alexander Pope. The book was published in May 1896. He was also working on a pornographic version of Lysistrata. This could not be openly published and was distributed the book privately to customers at his shop.

In December 1896 Beardsley suffered a violent haemorrhage at Boscombe. He moved to nearby Bournemouth for the mild climate and on 31st March 1897, he was received into the Catholic Church. Soon afterwards he wrote to Leonard Smithers about the work he had done for his illegal operation: "I implore you to destroy all copies of Lysistrata and bad drawings... By all that is holy, all obscene drawings." Smithers ignored his request.

Aubrey Beardsley moved to the French Riviera and stayed at the Hotel Cosmopolitan in Menton. He died on 16th March, 1898. Oscar Wilde wrote a letter to Leonard Smithers commenting: "There is something macabre and tragic in the fact that one who added another terror to life should have died at the age of a flower."

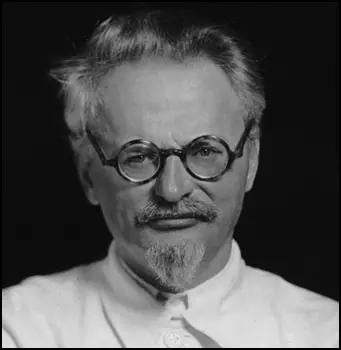

On this day in 1940 Leon Trotsky is murdered. Joseph Stalin ordered his NKVD agents to eliminate Trotsky. Ramon Mercader became a regular visitor while he was living in Mexico City. Trotsky's wife, Natalia Sedova later recalled that he visited them on 20th August, 1940.: "He (Trotsky) brushed off his blue blouse and slowly, silently started walking towards the house accompanied by Jacson (Mercader) and myself. I came with them to the door of Lev Davidovich's study; the door closed, and I walked into the adjoining room.... Not more than three or four minutes had elapsed when I heard a terrible, soul-shaking cry and without so much as realizing who it was that uttered this cry, I rushed in the direction from which it came. Between the dining room and the balcony, on the threshold, beside the door post and leaning against it stood... Lev Davidovich. His face was covered with blood, his eyes, without glasses, were sharp blue, his hands were hanging." Trotsky's book, Stalin (1941) was published after his death.

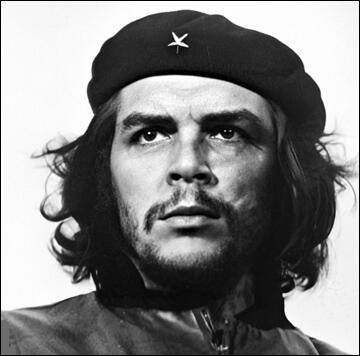

On this day in 1960 Che Guevara makes an important speech in Cuba.

Almost everyone knows that I began my career as a doctor a few years ago. When I began to study medicine, most of the concepts that I now have as a revolutionary were absent from my store of ideals. I wanted to succeed just as everyone wants to succeed. I dreamed of becoming a famous researcher; I dreamed of working tirelessly to aid humanity, but this was conceived as personal achievement. I was - as we all are - a product of my environment.

After graduating, due to special circumstances and perhaps also to my personality, I began to travel throughout America. Except for Haiti and the Dominican Republic, I have visited all the countries of Latin America. Because of the circumstances in which I made my trips, first as a student and later as a doctor, I perceived closely misery, hunger, disease - a father's inability to have his child treated because he lacks the money, the brutalization that hunger and

permanent punishment provoke in man until a father sees the death of his child as something without importance, as happens very often to the mistreated classes of our American fatherland. I began to realize then that there were things as important as being a famous researcher or as important as making a substantial contribution to medicine: to aid those people.

But I continued to be, as we always remain, a product of my environment and I wanted to aid those people with my personal effort. Already I had traveled much - at the time I was in Guatemala, Arbenz's Guatemala - and I began to make some notes on the norms that a revolutionary doctor should follow. I began to study the means of becoming a revolutionary doctor.

Then aggression came to Guatemala. It was the aggression of the United Fruit Company, the State Department, and John Foster Dulles - in reality the same thing - and their puppet, called Castillo Armas. The aggression succeeded, for the Guatemala people had not achieved the degree of maturity that the Cuban people have today. One day I chose the road of exile, that is, the road of flight, for Guatemala was not my country.

I became aware, then, of a fundamental fact: To be a revolutionary doctor or to be a revolutionary at all, there must first be a revolution. The isolated effort of one man, regardless of its purity of ideals, is worthless. If one works alone in some isolated corner of Latin America because of a desire to sacrifice one's entire life to noble ideals, it makes no difference because one fights against adverse governments and social conditions that prevent progress. To be useful it is essential to make a revolution as we have done in Cuba, where the whole population mobilizes and learns to use arms and fight together. Cubans have learned how much value there is in a weapon and in the unity of the people. So today one has the right and the duty of being, above everything else, a revolutionary doctor, that is, a man who uses his professional knowledge to serve the Revolution and the people.

Now old questions reappear: How does one actually carry out a work of social welfare? How does one correlate individual effort with the needs of society? To answer, we have to review each of our lives, and this should be done with critical zeal in order to reach the conclusion that almost everything that we thought and felt before the Revolution should be filed and a new type of human being should be created.

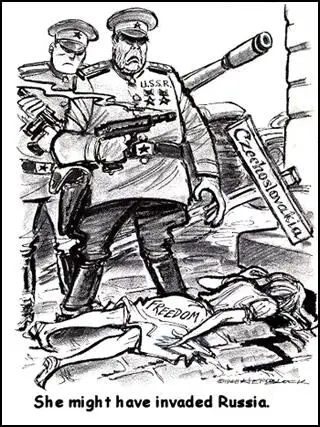

On this day in 1968, Czechoslovakia was invaded by members of the Warsaw Pact countries. In order to avoid bloodshed, the Czech government ordered its armed forces not to resist the invasion. Alexander Dubcek and Ludvik Svoboda were taken to Moscow and soon afterwards they announced that after "free comradely discussion" that Czechoslovakia would be abandoning its reform programme.

In April 1969 Dubcek was replaced as party secretary by Gustav Husak. The following year he was expelled from the party and for the next 18 years worked as a clerk in a lumber yard in Slovakia.

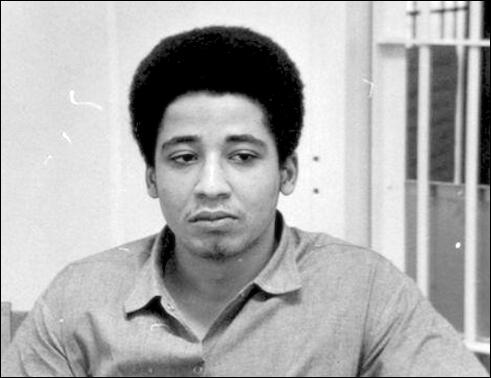

On this day in 1971 George Jackson is was gunned down in the prison yard at San Quentin. He was carrying a 9mm automatic pistol and officials argued he was trying to escape from prison. It was also claimed that the gun had been smuggled into the prison by Angela Davis. However, at her trial she was acquitted of all charges.

While in California's Soledad Prison Jackson and W. L. Nolen, established a chapter of the Black Panthers. On 13th January 1970, Nolen and two other black prisoners was killed by a prison guard. A few days later the Monterey County Grand Jury ruled that the guard had committed "justifiable homicide."

When a guard was later found murdered, Jackson and two other prisoners, John Cluchette and Fleeta Drumgo, were indicted for his murder. It was claimed that Jackson had sought revenge for the killing of his friend, W. L. Nolen.

On 7th August, 1970, George Jackson's seventeen year old brother, Jonathan, burst into a Marin County courtroom with a machine-gun and after taking Judge Harold Haley as a hostage, demanded that George Jackson, John Cluchette and Fleeta Drumgo, be released from prison. Jonathan Jackson was shot and killed while he was driving away from the courthouse.