On this day on 15th July

On this day in 1381 John Ball, the leader of the Peasants' Revolt, is hung, drawn and quartered. The king's officials were instructed to look out for John Ball. He was eventually caught in Coventry. He was taken to St Albans to stand trial. "He denied nothing, he freely admitted all the charges without regrets or apologies. He was proud to stand before them and testify to his revolutionary faith." He was sentenced to death, but William Courtenay, the Bishop of London, granted a two-day stay of execution in the hope that he could persuade Ball to repent of his treason and so save his soul.

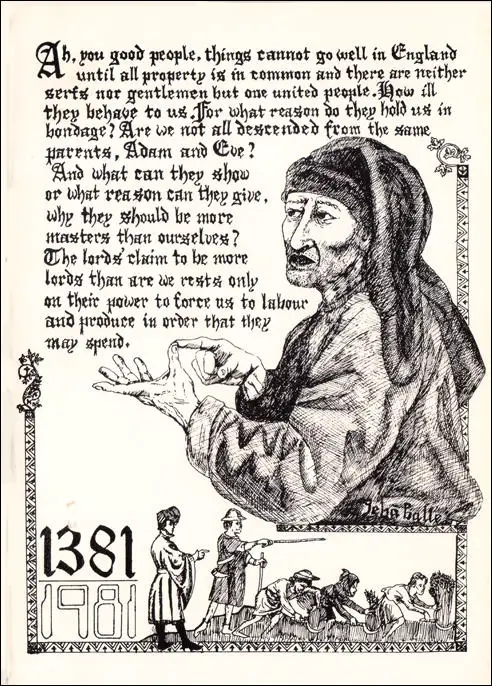

Modern portrait of John Ball by David Simkin (1981)

On this day in 1848 Punch Magazine writes about Women Chartists. "London is threatened with an irruption of female Chartists, and every male of experience is naturally alarmed.... We confess we are much more alarmed about the threatened rising of the ladies than we should be by the revolt of half the scamps in the metropolis. The women must be put down, as any unfortunate victim of female domination can testify. How then, are we to deal with the female Chartists? The police will never be got to act against them; for that gallant force knows how much the kitchens are in the hands of the gentler sex, and there is no member of the force who would willingly make himself an outcast from the hearth of the British basement. We have however, something to propose that will easily meet the emergency. A heroise who would never run from a man, would fly in dismay before an industrious flea or a burly black-beatle. We have only to collect together a good supply of cockroaches, with a fair sprinkling of rats, and a muster of mice, in order to disperse the largest and most ferocious crowd of females that ever was collected. We respectfully submit our proposition to Sir George Grey, as a certain specific for allaying female turbulence."

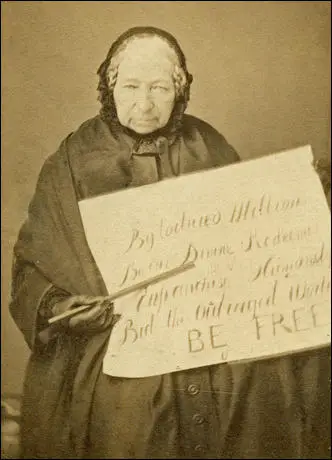

placard reads: "By tortured millions, By the Divine Redeemer,

Enfranchise Humanity, Bid the Outraged World, BE FREE".

On this day in 1858 Emmeline Goulden, the eldest daughter of ten children of Robert Goulden and Sophia Crane Gouldon, was born in Manchester on 15th July, 1858. Her father came from a family with radical political beliefs. Emmeline's grandfather had been one of the crowd at the Peterloo Massacre in 1819 took part in the campaigns against slavery and the Corn Laws.

The eldest daughter in a family of ten children, Emmeline was expected to look after her younger brothers and sisters. "A precocious child, she learned to read at an early age and was set the task of reading the daily newspaper to her father as he breakfasted, an activity that led to the development of an interest in politics."

Robert Gouldon was the successful owner of a cotton-printing company at Seedley. He had conventional ideas about education. Emmeline later recalled: "It was a custom of my father and mother to make the round of our bedrooms every night before going themselves to bed. When they entered my room that night I was still awake, but for some reason I chose to pretend I was asleep." She heard him say: "What a pity she wasn't born a lad." This incident had a long-term impact on Emmeline: "It was made quite clear that men considered themselves superior to women, and that women accepted this situation. I found this view of things difficult to reconcile with the fact that both my father and my mother were advocates of women having the vote".

Robert Goulden was a friend of John Stuart Mill and supported his campaign to get women the vote. These views were communicated to his children and during the 1868 General Election, Emmeline and her younger sister, Mary, took part in a feminist demonstration. According to Martin Pugh, the author of The Pankhursts (2001), she attended her first suffrage meeting in 1872, hosted by veteran campaigner, Lydia Becker.

After a short spell at a local school, Emmeline was sent to École Normale Supérieure, a finishing school in Paris in 1873. "The school was under the direction of Marchef Girard a woman who believed that girls' education should be quite as thorough as the education of boys. She included chemistry and other sciences in the course, and in addition to embroidery she had her girls taught bookkeeping. When I was nineteen I finally returned from school in Paris and took my place in my father's home as a finished young lady."

According to her biographer: "She returned to Manchester having learnt to wear her hair and her clothes like a Parisian, a graceful, elegant young lady, much more mature in appearance than girls of her age today, with a slender, svelte figure, raven black hair, an olive skin with a slight flush of red in the cheeks, delicately pencilled black eyebrows, beautiful expressive eyes of an unusually deep violet blue, above all a magnificent carriage and a voice of remarkable melody... She was romantic, believed in constancy, held flirtation degrading, would only give herself to an important man."

Soon after her returned to Manchester, she met the lawyer, Richard Pankhurst. A committed socialist, Richard was also a strong advocate of women's suffrage. Richard had been responsible for drafting an amendment to the Municipal Franchise Act of 1869 that had resulted in unmarried women householders being allowed to vote in local elections. Richard had served on the Married Women's Property Committee (1868-1870) and was the main person responsible for the drafting of the women's property bill that was passed by Parliament in 1870.

Richard and Emmeline were immediately attracted to each other and although there was a significant age difference, he was forty-four and she was only twenty, Richard Goulden gave permission for the marriage to take place. Emmeline had four children in the first six years of marriage: Christabel Pankhurst (1880), Sylvia Pankhurst (1882), Frank (1884) and Adela Pankhurst (1885).

Richard Pankhurst became a leading figure in radical politics in Manchester. The Spectator, a journal that supported the Liberal Party, warned about his extreme political views. "He has pledged himself to Home Rule and the repeal of the Crimes Bill, and the Irish have, therefore, accepted him; the moderate Liberals say he is better than a Tory, and the extreme Radicals are attracted by his ideas, which they see to be philanthropic... Dr. Pankhurst will not vote with Mr. Gladstone, but against him. The Premier is for unity and order ; Dr. Pankhurst is for Home Rule and the repeal of the Crimes Act. Mr. Gladstone is for household suffrage; Dr. Pankhurst for universal suffrage of both sexes... We admit that Dr. Pankhurst is honestly dreaming; and therefore we prefer... a sensible Tory to Dr. Pankhurst."

In 1886 the family moved to London where their home in Russell Square became a centre for gatherings of socialists and suffragists. They were also both members of the Fabian Society. At a young age, their children were encouraged to attend these meetings. This had a major impact on their political views. As June Purvis has pointed out: "Such experiences had a decisive effect on Christabel. Nothing she learned from the inadequate education offered by governesses or, when the family moved back to the north in 1893, at the high schools she attended - first in Southport and then in Manchester - compared with the political education she received at home."

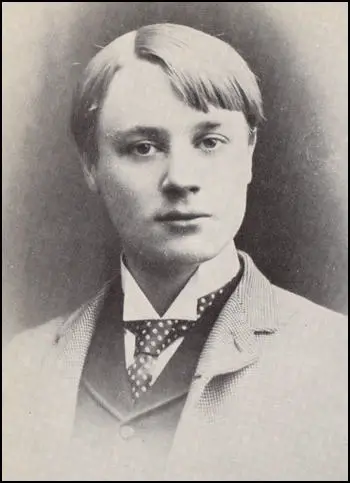

On this day in 1865 Alfred Harmsworth, the eldest child of Alfred Harmsworth (1837–1889), a barrister, and his wife, Geraldine Maffett Harmsworth (1838–1925), was born in Chapelizod near Dublin, on 15th July, 1865.

Over the next twenty years his mother gave birth to thirteen children. Harold (April 1868), Cecil (September 1869), Robert (November 1870), Hildebrand (March 1872), Violet (April 1873), Charles (December 1874), St John (May 1876), Maud (December 1877), Christabel (April 1880), Vyvyan (April 1881), Muriel (May 1882) and Harry (October 1885).

His father moved the family to London in 1867. His father's career did not prosper in England. The main reason for this was that he was an alcoholic. His own father, Charles Harmsworth, had also been an alcoholic, dying at fifty-three of cirrhosis of the liver. "Alfred's drinking would become the central problem of his wife's life, and later the lives of his children."

Alfred's brother, Harold Harmsworth, later recalled that the boys suffered a traumatic experience when they were young. A neighbour, who was a City stockbroker, was made bankrupt and this resulted in him killing all the members of his family before committing suicide. It seems this event motivated them to become financially successful.

According to J. Lee Thompson, "Alfred Harmsworth... formed a strong - some would later say fanatical - bond with his mother, who became the anchor of the family, holding it together in a struggle to keep up respectable, middle-class appearances, even as their income fell perilously closer to working-class level. Following her upright example, in later life he did not swear or gamble. A lifelong disgust for drunkenness was undoubtedly a reaction to his father's weakness and addiction."

Alfred began his education at Stamford Grammar School in Lincolnshire. In 1878 went as a day boy to Henley House School, Hampstead, in 1878, where he showed an early interest in journalism by publishing the school magazine. Its most popular feature was entitled "Answers to Correspondence", a question-and-answer column. He was an indifferent scholar but was good at sport and was captain of both the cricket and the football teams."

By 1880 Alfred Harmsworth was an occasional reporter on the Hampstead and Highgate Express. After leaving school Harmsworth found work with Youth, an illustrated magazine for boys, owned by the Illustrated London News. In 1886 he was employed by Edward Iliffe to edit one of his magazine, Bicycling News. He employed a woman correspondent, Lillias Campbell Davidson, with "an eye to encouraging women to take up biking."

The great publishing success at the time was Tit-Bits, a magazine that was selling 900,000 copies a month. Published by George Newnes, the magazine catered for those people who had been taught to read as a result of the 1870 Education Act and contained "scraps of interesting and entertaining information". Harmsworth described this new audience as being "thousands of boys and girls… who are aching to read. They do not care for the ordinary newspaper. They have no interest in society, but will read anything which is simple and is sufficiently interesting".

Harmsworth, now aged twenty, became a regular contributor to the magazine. He told his friend, Max Pemberton: "George Newnes has got hold of a bigger thing than he imagines. He is only at the very beginning of a development which is going to change the whole face of journalism. I shall try to get in with him. We could start one of those papers for a couple of thousands pounds, and we ought to be able to find the money. At any rate, I am going to make the attempt."

However, raising the necessary money for this new magazine was very difficult. In the meantime, much to his mother's disapproval, Harmsworth married Mary Milner, daughter of Robert Milner of Kidlington, Oxfordshire, a merchant with West India interests. The couple were married on 11th April 1888. His mother predicted they would have "many children and no money". She was wrong on both counts as the marriage was childless.

Eventually, with the help of his brother, Harold Harmsworth, obtained enough money, about £1,000, to publish his magazine, Answers to Correspondents. It has been claimed that "Harold had to convert Alfred's energy and genius into a paying proposition, and everything depended upon his succeeding at this task. This meant he had to exercise the most painstaking and minute control over outgoings, both financial and creative - the two almost inevitably going hand in hand."

The first edition of the magazine, costing one penny, was published on 2nd June, 1888. He told his readers that every question sent in would be answered by post, and the answers of those of general interest would be published in the magazine. Initially, Alfred had to pretend that he had received questions. Even when genuine queries came in, they were rarely suitable.

The formula used by the magazine was an attempt to provide an excuse for printing miscellaneous articles. For example, he invented a question on the diet of Queen Victoria. The magazine claimed: "The Queen's favourite foods are boiled mutton, of which she partakes at least twice a week, venison, salmon, boiled fowl, and silverside of beef." Other articles based on made-up questions included "An Electrical Flying Machine", "Horseflesh as Food" and "Why are no bus conductors bald?"

In an early edition of the magazine he condemned the way in which "shop boys and factory hands, pit boys, and telegraph boys, devour them eagerly and fill their foolish brains with rubbish about highwaymen, pirates, and other objectionable people". However, as these subjects were popular, Harmsworth soon changed his mind about the matter and published articles on gory issues such as "what it felt like to be hanged, or speculated as to how long a severed head might be conscious after beheading".

Harmsworth also ran a large number of competitions such as guessing how many people walked across London Bridge in a day. His most ingenious competitions was to ask readers to vote for "the ten greatest advertisers in Great Britain". This enabled him to print the names of firms he wanted to have as advertisers as well as interviews with some of them. He also published a list of the first twenty-three that the readers voted for during the competition.

Harmsworth's most successful innovation was a puzzle called "Pigs in Clover" that involved getting little rolling balls in a glass box into the right holes in order to spell the word "Answers". It was a terrific success, with Answers Puzzle Clubs being formed all over the country. Two hundred contestants gathered at the London offices to compete for a £50 national prize awarded to the swiftest solution. It was later claimed that over two and a half million of these puzzles were sold worldwide.

Sales of the magazine rose steadily but slowly. He discovered that puzzles were extremely popular and one edition with a special competition pushed up sales to 30,000 a week. At the first annual meeting, in June 1889, reported a circulation of 48,000 and a gross profit for the year of £1,097 3s 1d. It has been argued that "Harold Harmsworth's management skills and cost-cutting genius proved their worth".

In October 1889 Alfred Harmsworth came up with another new contest was announced which promised which promised "A Pound a Week for Life!" The contest offered a pound a week for life to the person who came closest to guessing the amount of gold coinage in the Bank of England. Entries had to be on postcards and include the signatures and addresses of five "witnesses" who were not relatives or living at the same address. In all, 712,218 postcards were received. This brought the attention of millions of possible subscribers.

On the day the gold coinage figure was posted outside the Bank of England in Threadneedle Street, police had to be called to control the crowds. The prize was won by C. D. Austin of the Royal Engineers estimated the amount to within £2 of the correct figure. He married his sweetheart immediately, but he died eight years later of tuberculosis. Harmsworth sent his widow a cheque for £50.

Despite the great success of this promotion, circulation only reached 200,000 while Tit-Bits sold over 500,000. He decided to launch a new competition, "£2 a Week for Life". The government immediately intervened and pointed out that the recent Lotteries Act, offering prizes for guesswork was illegal. The magazine eventually reached 300,000 after it starting publishing serial stories written by Arthur Conan Doyle.

On this day in 1943 John Steinbeck wrote about Britain's Dig for Victory campaign.

On the edges of American airfields and between the barracks of troops in England it is no unusual thing to see complicated and carefully tended vegetable gardens. No one seems to know where the idea originated, but these gardens have been constantly increasing. It is fairly common now that a station furnishes a good part of its own vegetables and all of its own salad greens.

The idea, which had as its basis, probably, the taking up of some of the free time of men where there were few entertainment facilities, has proved vastly successful. The gardens are run by the units and worked by the groups, but here and there a man may go out on his own and try and raise some strange seed which is not ordinarily seen in this climate. In every unit there is usually some man who knows about such things who advises on the planting, but even such men are often at a loss because vegetables are different here from the vegetables at home.

The things that the men want to raise most, in order of choice, are green corn, tomatoes, and peppers. None of these do very well in England unless there is a glass house to build up sufficient heat. Tomatoes are small; there are none of those master beefsteak tomatoes bursting with juice. It is a short, cool season. Green corn has little chance to mature and the peppers must be raised under glass. Nevertheless, every care is taken to raise them. Men who are homesick seem to take a mighty pleasure in working with the soil.

The gardens usually start out ambitiously. Watermelons and cantaloupes are planted and they have practically no chance of maturing at this latitude, where even cucumbers are usually raised in glass houses, but gradually some order grows out of the confusion. Lettuce, peas, green beans, green onions, potatoes do very well here, as do cabbages and turnips and beets and carrots. The gardens are lush and well tended. In the evenings, which are very long now, the men work in the beds. It does not get dark until eleven o'clock, there are only so many movies to be seen, English pubs are not exciting, but there does seem to be a constant excitement about the gardens, and the produce that comes from them tastes much better than that purchased in the open market.

On this day in 1945 General Leslie Groves issues press statement on the testing of the first atom bomb. "A remotely located ammunition magazine containing a considerable amount of high explosives and pyrotechnics exploded. There was no loss of life or injury. Weather conditions affecting the content of gas shells exploded by the blast may make it desirable for the Army to evacuate temporarily a few civilians from their homes."

On this day in 1959 Alice Hamilton, letter to Felix Frankfurter, about the treatment of left-wing activists "Why are we the only western country that lives in terror of native Communists. All the European countries have open and above-board political Communist parties some even have members of Parliament or whatever, and they do not have Un-Dutch Activities Committee. Look at the contrast between the English treatment of Klaus Fuchs and our treatment of the Rosenbergs. Fuchs is a scientist (which Rosenberg was not) he gave valuable atomic secrets to the Russians (Urey testified that Rosenberg did not know enough to do that) he confessed (the Rosenbergs refused to, though offered their lives as reward) Fuchs acted during the war, the Rosenbergs during peace."