On this day on 14th August

On this day in 1716 The London Gazette publishes article about the Newcomen Steam-Engine. "Whereas the invention for raising water by the impellant force of fire, authorized by Parliament, is lately brought to the greatest perfection, and all sorts of mines, etc., may be thereby drained and water raised to any height with more ease and less charge than by the other methods hitherto used, as is sufficiently demonstrated by diverse engines of this invention now at work in the several counties of Stafford, Warwick, Cornwall, and Flint. These are therefore, to give notice that if any person shall be desirous to treat with the proprietors for such engines, attendance will be given for that purpose every Wednesday at the Sword Blade Coffee House in Birchin Lane, London."

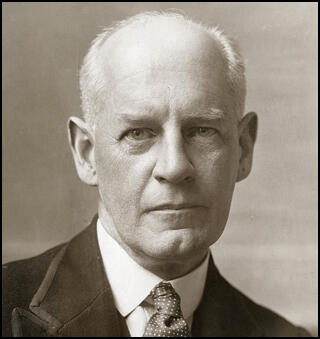

On this day in 1867 novelist John Galsworthy, the son of a wealthy solicitor, was born at Kingston Hill in Surrey . Educated at Harrow and New College, Oxford, Galsworthy was called to the bar in 1890, but instead decided to become a writer.

Galsworthy's first collection of short-stories, From the Four Winds, was published in 1897. This was followed by the novel, The Island Pharisees (1904). These books sold poorly and Galsworthy later pointed out that for "eleven years, I made not one penny out of what I, but practically no others, counted as my profession."

Galsworthy's first real success was the play The Silver Box (1906). Later that year, his novel, The Man of Property, the first of his celebrated Forsyte Saga series was published.

Galsworthy held progressive views and supported prison reform, votes for women and opposed censorship. His plays Strife (1909) and Justice (1910) dealt with the themes of poverty, class and injustice.

On the outbreak of the First World War Galsworthy was 47 years old. Too old to fight, he worked in France at the Benevole Hospital for disabled soldiers. He also signed over his family house as a rest home for members of the British Army recovering from war injuries.

Galsworthy was also recruited by Charles Masterman, the head of the War Propaganda Bureau (WPB), to write material on behalf of the British government. This included articles in the New York Times, the New York Tribune, Scribner's Magazine and the Literary Digest. Unlike some of those recruited by the WPB, Galsworthy refused to encourage the public to hate the enemy. He instead concentrated on the need to give support to disabled and wounded soldiers. Galsworthy's collected articles for the WPB were published in A Sheaf (1916) and Another Sheaf (1917).

After the war Galsworthy completed the Forsyte Saga with In Chancery (1920) and To Let (1921). The second part of the Forsyte chronicles was made up of The White Monkey (1924), The Silver Spoon (1926) and Swan Song (1928).

Galsworthy was now a highly successful author and he was able to purchase a 15-room mansion at Bury in Sussex. John Galsworthy, who received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1932, died from a brain tumour on 30th January, 1933.

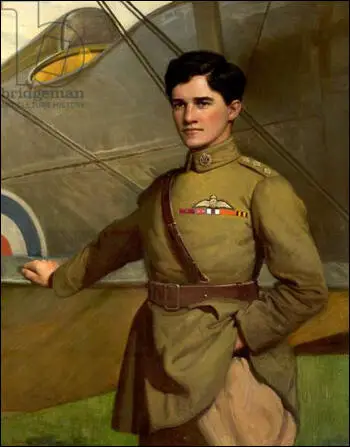

On this day in 1896 Albert Ball was born in Nottingham. An engineering student when the First World War started, he joined the Sherwood Foresters before transferring to the Royal Flying Corps in 1915. Considered an only average pilot, he began his fighting career in May 1916. At first he concentrated on ambushing poorly defended two-seater German planes.

With his confidence growing, Ball began to make single-handed attacks on German planes flying in formation. His preferred position was a few yards directly beneath his opponent who he would shoot by tilting up his single wing-mounted Lewis gun. Flying a Nieuport 17, Ball supported the offensive at the Somme. By the time he was sent back to England in October 1916, Ball was credited with thirty victories.

Appointed flight commander in No. 56 Squadron, Ball began flying the recently developed S.E.5. On the morning of 6th May 1917, Ball brought down a Albatros D-II. Later that evening he was seen in combat with a German single-seater. The pair crashed in deep cloud and Ball's body was later found in the wreckage. By the time of his death, Ball, who was only twenty years old, had won the Victoria Cross, the Military Cross and the Croix de Guerre.

On this day in 1914 The Times reports that Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) member, Norah Dacre Fox, makes controversial statement about the war. "Mrs Dacre Fox said that for the first time since the war broke out there was an open fight between the British public and German influence at work in the country. We had to make a clean sweep of all persons of German blood, without distinction of sex, birthplace, or nationality. Never had the time been so ripe for action; never would it be so favourable again. If we allowed the opportunity to pass now, German influence, which at the present moment was hampering and hindering the War Cabinet in its prosecution of the war, would become more firmly entrenched than ever in this country. The report of the committee set up by Mr Lloyd George was an exceedingly weak report, and its recommendations were useless. They wanted to see every person of German blood in this country under lock and key. They must make the politicians move. Any person in this country, no matter who he was or what his position, who was suspected of protecting German influence, should be tried as a traitor, and, if necessary, shot. There must be no compromise and no discrimination."

On this day in 1984 J. B. Priestley dies.

John Boynton Priestley, the only child of Jonathan Priestley (1868–1924), and his first wife, Emma Holt (1865–1896), was born in Manningham, a suburb of Bradford on 13th September, 1894. Despite being the son of an illiterate mill worker, his father became a school teacher. His mother died when he was only two years old and in in 1898 his father married Amy Fletcher, whom Priestley described as a loving stepmother.

Priestley was educated at Whetley Lane Primary School, and then, on a scholarship, Belle Vue High School. Bored with school he left education and the age of sixteen and found work as a clerk for a wool firm in Bradford. He joined the Labour Party and began writing a column in their weekly newspaper, The Bradford Pioneer.

On the outbreak of the First World War Priestley immediately joined the British Army. He later recalled: "It is not true, as some critics of the British high command have suggested, that Kitchener's army consisted of brave but half-trained amateurs, so much pitiful cannon-fodder. In the earlier divisions like ours, the troops had months and months of severe intensive training. Our average programme was ten hours a day, and nobody grumbled more than the old regulars who had never been compelled before to do so much and for so long."

Priestley was sent to France and served on the Western Front. He wrote to his father on 27th September, 1915: "In the last four days in the trenches I don't think I'd eight hours sleep altogether. It is frightfully difficult to walk in the trenches owing to the slippery nature of things, the most appalling thing is to see the stretcher bearers trying to get the wounded men up to the Field Dressing station. On Saturday morning we were subjected to a fearful bombardment by the German artillery; they simply rained shells. One shell burst right in our trench - and it was a miracle that so few - only four - were injured. I escaped with a little piece of flesh torn out of my thumb. But poor Murphy got a shrapnel wound in the head - a horrible great hole - and the other two were the same. They were removed soon after and I don't know how they are going on."

Priestley took part in the Battle of Loos and in 1917 he accepted a commission. After being wounded later that year he was sent back to England for six months. Soon after returning to the Western Front he endured a German gas attack. Treated at Rouen he was classified by the Medical Board as unfit for active service and was transferred to the Entertainers Section of the British Army. He wrote over 40 years later: "I felt as indeed I still feel today and must go on feeling until I die, the open wound, never to be healed, of my generation's fate, the best sorted out and then slaughtered, not by hard necessity but by huge, murderous public folly."

When Priestley left the army he became a student at Trinity Hall. While at Cambridge University he gained valuable experience by writing for the Cambridge Review. After completing a degree in Modern History and Political Science, Priestley found work as theatre reviewer with the Daily News. He also contributed articles to the Spectator.

Priestley married Pat Emily Tempest on 29th June 1921. His first book, Brief Diversions (1922) a collection of epigrams, anecdotes, and stories. His second book, Papers from Lilliput, was a series of essays on personalities past and present.He also contributed articles to the Spectator, The Bookman, the Saturday Review, and the Times Literary Supplement.

In March 1923 Priestley's wife gave birth to their first child, Barbara, to be followed prematurely in April 1924 by a second daughter, Sylvia, when it was discovered that Pat was suffering from terminal cancer. Priestley wrote to a friend that he was "so deep in despair I didn't know what to do with myself". However, it was not long long before he was having an affair with Jane Wyndham Lewis, the wife of D. B. Wyndham Lewis, which resulted in the birth of a daughter, Mary, in March 1925. Priestley had a number of affairs and in later life he admitted he "enjoyed the physical relations with the sexes … without the feelings of guilt which seems to disturb some of my distinguished colleagues". Pat Priestley died on 25th November 1925. The following year he married Jane Wyndham Lewis.

Priestley's early critical writings such as The English Comic Characters (1925), The English Novel (1927) and English Humour (1929) established his reputation as an important commentator on literature. With financial support from his friend, Hugh Walpole, Priestley wrote, The Good Companions, a novel 250,000 words long. It was completed in March 1929, and published in July. As his biographer, Judith Cook pointed out: "Sales started slowly, but by Christmas the publishers Heinemann had to use taxis to rush copies to bookshops, so great was the demand; it became one of the best-sellers of the century."

J. B. Priestley followed this with what some consider his best novel, Angel Pavement (1930). He also wrote several popular plays such as Dangerous Corner (1932). Priestley also became increasingly concerned about social problems. This is reflected in English Journey (1934), an account of his travels through England. The author of J. B. Priestley (1998) has argued: "He travelled from the south to the north of England, brilliantly describing in bitter prose the poverty and unemployment of the time." Priestley followed this was the plays, Eden End (1934), I Have Been Here Before (1937), Time and the Conways (1937), When we are Married (1938), and Johnson over Jordan (1939).

During the Second World War Priestley became the presenter of Postscripts, a BBC Radio radio programme that followed the nine o'clock news on Sunday evenings. Starting on 5th June 1940, Priestley built up such a following that after a few months it was estimated that around 40 per cent of the adult population in Britain was listening to the programme.

On 21st July, 1940, he argued: "We cannot go forward and build up this new world order, and this is our war aim, unless we begin to think differently one must stop thinking in terms of property and power and begin thinking in terms of community and creation. Take the change from property to community. Property is the old-fashioned way of thinking of a country as a thing, and a collection of things in that thing, all owned by certain people and constituting property; instead of thinking of a country as the home of a living society with the community itself as the first test."

Graham Greene pointed out: "Priestley became in the months after Dunkirk a leader second only in importance to Mr Churchill. And he gave us what our other leaders have always failed to give us - an ideology." Some members of the Conservative Party complained about Priestley expressing left-wing views on his radio programme. Margaret Thatcher has argued that "J.B. Priestley gave a comfortable yet idealistic gloss to social progress in a left-wing direction." As a result Priestley made his last talk on 20th October 1940. These were later published in book form as Britain Speaks (1940).

Priestley and a group of friends now established the 1941 Committee. One of its members, Tom Hopkinson, later claimed that the motive force was the belief that if the Second World War was to be won "a much more coordinated effort would be needed, with stricter planning of the economy and greater use of scientific know-how, particularly in the field of war production." Priestley became the chairman of the committee and other members included Edward G. Hulton, Kingsley Martin, Richard Acland, Michael Foot, Tom Winteringham, Vernon Bartlett, Violet Bonham Carter, Konni Zilliacus, Victor Gollancz, Storm Jameson and David Low.

In December 1941 the committee published a report that called for public control of the railways, mines and docks and a national wages policy. A further report in May 1942 argued for works councils and the publication of "post-war plans for the provision of full and free education, employment and a civilized standard of living for everyone."

Some members of the Labour Party disapproved of the electoral truce between the main political parties during the Second World War and in 1942 Priestley and Richard Acland formed the socialist Common Wealth Party (CWP). The party advocated the three principles of "Common Ownership", "Vital Democracy" and "Morality in Politics". The party favoured public ownership of land and Acland gave away his Devon family estate of 19,000 acres (8,097 hectares) to the National Trust.

The CWP decided to contest by-elections against Conservative candidates. They needed the support of traditional Labour supporters. Tom Wintringham wrote in September 1942: "The Labour Party, the Trade Unions and the Co-operatives represent the worker's movement, which historically has been, and is now, in all countries the basic force for human freedom... and we count on our allies within the Labour Party who want a more inspiring leadership to support us." Large numbers of working people did support the CWP and this led to victories for Richard Acland in Barnstaple and Vernon Bartlett in Bridgwater.

Over the next two years the CWP also had victories in Eddisbury (John Loverseed), Skipton (Hugh Lawson) and Chelmsford (Ernest Millington). George Orwell wrote: "I think this movement should be watched with attention. It might develop into the new Socialist party we have all been hoping for, or into something very sinister." Orwell, like Kitty Bowler, believed that Richard Acland had the potential to become a fascist leader.

Negotiations went on between the Common Wealth Party and the Labour Party about the 1945 General Election. Acland demanded the right to contest 43 selected Conservative-held seats without opposition from Labour in return for not contesting all other constituencies. After this offer was rejected, Tom Wintringham met with Herbert Morrison, and suggested this be lowered to "twenty middle-class Tory seats". Morrison made it clear that his party was unwilling to agree to any proposal that involved Labour candidates standing-down.

Tom Wintringham was commissioned by Victor Gollancz to write a book, Your MP. The book sold over 200,000 copies and was a best-seller during the 1945 general election campaign. The book contained an appendix detailing how 310 Conservative MPs voted in eight key debates between 1935 and 1943. However, this book seemed to help the Labour Party as they ended up with 393 seats, whereas only one of the CWP twenty-three candidates was successful - Ernest Millington at Chelmsford, where there was no Labour contestant.

In 1946 Priestley wrote one of his best-known plays, An Inspector Calls. It was later turned into a film starring Alastair Sim. However, as his biographer, Judith Cook, has pointed out: "While Priestley's plays have always been popular outside London and abroad, it became fashionable over the years to consider them too old-fashioned for metropolitan audiences."

Priestley began an affair with Jacquetta Hawkes, the wife of the archaeologist Professor Christopher Hawkes. This resulted in a divorce case and the "judge's subsequent scathing remarks about Priestley made headlines in the national press". On 23rd July 1953 he married Jacquetta and the couple moved to Kissing Tree House on the outskirts of Stratford upon Avon.

J. B. Priestley continued to write on politics and literature. His article for the New Statesman entitled Russia, the Atom and the West, attacked the decision by Aneurin Bevan to abandon his policy of unilateral nuclear disarmament (2nd November, 1957). The article resulted in a large number of people writing letters to the journal supporting Priestley's views. Kingsley Martin, the editor of the magazine organised a meeting of people inspired by Priestley and as result they formed the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). Early members of this group included Priestley, Bertrand Russell, Fenner Brockway, Victor Gollancz, Canon John Collins and Michael Foot.

In his later years Priestley wrote the highly acclaimed, Literature and Western Man (1960) and two volumes of autobiography: Margin Released (1962) and Instead of the Trees (1977). Diana Collins, was a fellow member of CND. She later argued: "He (J. B. Priestley) was a lovely man. He believed and practised some of the best virtues: integrity; honesty; loyalty to his old friends. He was kind, generous, immensely understanding and I never heard him flatter anybody. He was a wonderful giver but not a good receiver because he didn't want to be beholden to anybody. Behind the big public figure he was really a shy man who believed in old-fashioned courtesy. And what a lovely father figure he made. Deeply aware? Of course he was deeply aware. Sometimes in the afternoons I noticed a great melancholy overtaking him. He would talk then of the individual being a bubble on the stream of life which quietly burst when its day was done and disappeared downstream, but he stopped short of the idea of complete annihilation."

Judith Cook has pointed out: "J. B. Priestley was a big man in every respect, in bulk, in his prodigious appetite for work, and in his generosity of spirit. He was a man of many loves; he loved women and women loved him, not only his wives and those with whom he had affairs, but also those who became his friends. He loved the old music-hall, theatre, music, particularly the great German composers (he was a good pianist), classic literature, and the English countryside, especially the Yorkshire dales. In his later years he also became an accomplished painter in watercolour and gouache. He was a confirmed grumbler, could be extremely difficult when the mood took him, and never suffered fools gladly, even when it might have been politic to do so. The darker side of his nature never left him, however, and in later years he increasingly fell prey to depression."

On this day in 1985 American blacklisted actress Gale Sondergaard dies.

Gale Sondergaard was born in Litchfield, Minnesota, on 15th February, 1899. She became an actress and while working for the Theatre Guild met and married Herbert Biberman. The couple moved to Hollywood and she acted in 38 films in thirteen years. This included Anthony Adverse (1936), The Life of Emile Zola (1937), Sons of Liberty (1939), The Mark of Zorro (1940), A Night to Remember (1943), and Road to Rio (1947).

After the Second World War the House of Un-American Activities Committee began an investigation into the Hollywood Motion Picture Industry. In September 1947, the HUAC interviewed 41 people who were working in Hollywood. These people attended voluntarily and became known as "friendly witnesses". During their interviews they named several people who they accused of holding left-wing views. This included Gondergaard and her husband Herbert Biberman.

Biberman appeared before the HUAC on 29th October, 1947, but like, Alvah Bessie, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Dalton Trumbo, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., Samuel Ornitz and John Howard Lawson, he refused to answer any questions. Known as the Hollywood Ten, they claimed that the 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to do this. The House of Un-American Activities Committee and the courts during appeals disagreed and all were found guilty of contempt of Congress and Herbert Biberman was sentenced to six months in Texarkana Prison and fined $1,000.

Blacklisted by the studios, Sondergaard did not appear in another Hollywood film until Slaves (1969). This was followed by Savage Intruder (1970), Pleasantville (1976), The Return of a Man Called Horse (1976) and Echoes (1983).