On this day on 10th July

On this day in 1553 Lady Jane Grey takes the throne of England. King Edward VI died on 6th July, 1553. Three days later one of Northumberland's daughters came to take her to Syon House, where she was ceremoniously informed that the king had indeed nominated her to succeed him. Jane was apparently "stupefied and troubled" by the news, falling to the ground weeping and declaring her "insufficiency", but at the same time praying that if what was given to her was "‘rightfully and lawfully hers", God would grant her grace to govern the realm to his glory and service.

On 10th July, Queen Jane arrived in London. An Italian spectator, witnessing her arrival, commented: "She is very short and thin, but prettily shaped and graceful. She has small features and a well-made nose, the mouth flexible and the lips red. The eyebrows are arched and darker than her hair, which is nearly red. Her eyes are sparkling and reddish brown in colour." (13) Guildford Dudley, "a tall strong boy with light hair’, walked beside her, but Jane apparently refused to make him king, saying that "the crown was not a plaything for boys and girls."

Jane was proclaimed queen at the Cross in Cheapside, a letter announcing her accession was circulated to the lords lieutenant of the counties, and Bishop Nicolas Ridley of London preached a sermon in her favour at Paul's Cross, denouncing both Mary and Elizabeth as bastards, but Mary especially as a papist who would bring foreigners into the country. It was only at this point that Jane realised that she was "deceived by the Duke of Northumberland and the council and ill-treated by my husband and his mother".

Mary, who had been warned of what Dudley had done and instead of going to London as requested by Dudley, she fled to Kenninghall in Norfolk. As Ann Weikel has pointed out: "Both the earl of Bath and Huddleston joined Mary while others rallied the conservative gentry of Norfolk and Suffolk. Men like Sir Henry Bedingfield arrived with troops or money as soon as they heard the news, and as she moved to the more secure fortress at Framlingham, Suffolk, local magnates like Sir Thomas Cornwallis, who had hesitated at first, also joined her forces."

Mary summoned the nobility and gentry to support her claim to the throne. Richard Rex argues that this development had consequences for her sister, Elizabeth: "Once it was clear which way the wind was blowing, she (Elizabeth) gave every indication of endorsing her sister's claim to the throne. Self-interest dictated her policy, for Mary's claim rested on the same basis as her own, the Act of Succession of 1544. It is unlikely that Elizabeth could have outmanoeuvred Northumberland if Mary had failed to overcome him. It was her good fortune that Mary, in vindicating her own claim to the throne, also safeguarded Elizabeth's."

The problem for Dudley was that the vast majority of the English people still saw themselves as "Catholic in religious feeling; and a very great majority were certainly unwilling to see - King Henry's eldest daughter lose her birthright." When most of Dudley's troops deserted he surrendered at Cambridge on 23rd July, along with his sons and a few friends, and was imprisoned in the Tower of London two days later. Tried for high treason on 18th August he claimed to have done nothing save by the king's command and the privy council's consent. Mary had him executed at Tower Hill on 22nd August. In his final speech he warned the crowd to remain loyal to the Catholic Church.

Queen Mary told a foreign ambassador that her conscience would not allow her to have Jane put to death. Jane was given comfortable quarters in the house of a gentleman gaoler. The anonymous author of the Chronicle of Queen Jane and of Two Years of Queen Mary (c. 1554), dropped in for dinner, finding the Lady Jane sitting in the place of honour. She made the visitor welcome and asked for news of the outside world, before going on to speak gratefully of Mary - "I beseech God she may long continue" and made a fierce attack against John Dudley, the Duke of Northumberland: "Woe worth him! He hath brought me and our stock in most miserable calamity by his exceeding ambition".

Jane, together with Guildford Dudley and two more of his brothers, stood trial for treason on 19th November. They were all found guilty but foreign ambassadors in London reported that Jane's life would be spared. Mary's attitude towards Jane changed when her father, Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, joined the rebellion led by Sir Thomas Wyatt against her proposed marriage to Philip of Spain. Although there is any evidence that Jane had any foreknowledge of the conspiracy, "her very existence as a possible figurehead for protestant discontent made her an unacceptable danger to the state". Mary, now agreed with her advisers and the date of Jane's execution was fixed for 9th February, 1554. However, she was still willing to forgive Jane and sent John Feckenham, the new dean of St Paul's, over to the Tower of London in an attempt to see if he could convert this "obdurate heretic". However, she refused to change her Protestant beliefs.

Jane watched the execution of her husband from the window of her room in the Tower of London. She then came out leaning on the arm of Sir John Brydges, Lieutenant of the Tower. "Lady Jane was calm, although. Elizabeth and Ellen (her two women attendants) wept... The executioner kneeled down and asked for forgiveness, which she gave most willingly... she said: "I pray you dispatch me quickly."

Jane then made a brief speech: "Good people, I am come hither to die, and by a law I am condemned to the same. The fact, indeed, against the queen's highness was unlawful, and the consenting thereunto by me: but touching the procurement and desire thereof by me or on my behalf, I do wash my hands thereof in innocency, before God, and the face of you, good Christian people, this day' and therewith she wrung her hands, in which she had her book." Kneeling, she repeated the 51st Psalm in English.

On this day in 1875 Mary McLeod Bethune, the fifteenth of seventeenth children, was born in Mayesville, South Carolina. Both of her parents were former slaves who had been emancipated after the Civil War. Mary received no schooling until the Trinity Presbyterian Mission School opened in 1885.

Inspired by the teaching of Emma Jane Wilson, Mary decided that she wanted a career in education. After graduating from Scotia Seminary, she spent six years teaching in North Carolina. Mary trained to become an African missionary at the Bible Institute for Home and Foreign Missions in Chicago. However, she was rejected by the Presbyterian Mission Board because it did not accept African Americans for this work.

Bethune returned to teaching and found work at the Haines Institute in Augusta, Georgia. This was followed by a spell at the Kendall Institute in Sumner, South Carolina, where she met and married Albert Bethune. The couple moved to Palatka, Florida and while her husband worked as a porter, Mary opened her own school.

In 1904 Bethune established the Daytona Educational and Industrial Institute for Negro Girls. The school was a great success and by 1922 it had 300 students and 25 staff. The following year it was merged with the Cookman Institute for Men and from 1929 became known as the Bethune-Cookman College.

Bethune played an active role in the civil rights movement. A member of the NAACP, Bethune defied Jim Crow customs and all seating in her schools were desegregated. Although threatened by the Ku Klux Klan, Bethune and her staff always voted in elections.

Bethune was also president of the National Association of Colored Women (1924 to 1928) and in 1935 established the National Council of Negro Women. In these posts Bethune campaigned against lynching and discrimination in employment.

In 1936 President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Bethune as administrative assistant for Negro Affairs. She was also elected president of the NAACP in 1940 and during the Second World War she campaigned for desegregation in the armed forces.

Mary McLeod Bethune died on 18th May, 1955, at Daytona Beach, Florida. book,

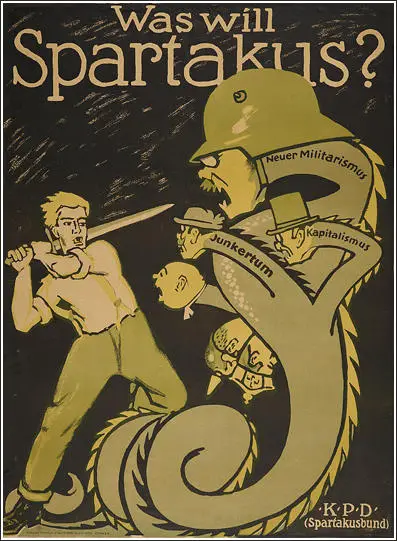

On this day in 1916 Rosa Luxemburg, Franz Mehring, Ernest Meyer, Julian Marchlewski and other leaders of the Spartacus League were arrested for anti-war activities. Leo Jogiches now became the leader of the Spartacus League and the editor of its newspaper, Spartakusbriefe. Luxemburg, wrote regularly for each edition, sometimes writing three-quarters of a whole issue. She also worked on her book, Introduction to Economics.

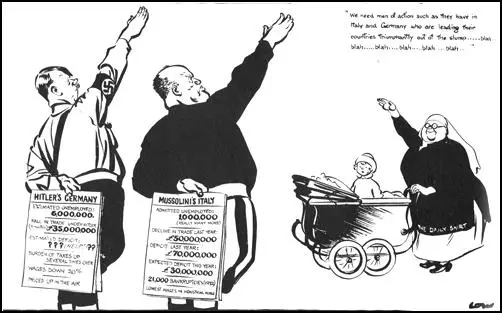

On this day in 1933 Lord Rothermere praises the policies of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany in The Daily Mail.

I urge all British young men and women to study closely the progress of the Nazi regime in Germany. They must not be misled by the misrepresentations of its opponents. The most spiteful distracters of the Nazis are to be found in precisely the same sections of the British public and press as are most vehement in their praises of the Soviet regime in Russia.

They have started a clamorous campaign of denunciation against what they call "Nazi atrocities" which, as anyone who visits Germany quickly discovers for himself, consists merely of a few isolated acts of violence such as are inevitable among a nation half as big again as ours, but which have been generalized, multiplied and exaggerated to give the impression that Nazi rule is a bloodthirsty tyranny.

The German nation, moreover, was rapidly falling under the control of its alien elements. In the last days of the pre-Hitler regime there were twenty times as many Jewish Government officials in Germany as had existed before the war. Israelites of international attachments were insinuating themselves into key positions in the German administrative machine. Three German Ministers only had direct relations with the Press, but in each case the official responsible for conveying news and interpreting policy to the public was a Jew.

On this day in 1943 Archbishop William Temple, in an article in the Evening Standard, comments on people's behaviour during the Blitz. "I commend the endurance, mutual helpfulness, and constancy, which during the 'Blitz' reached heroic proportions but people are not conscious of injuring the war effort by dishonesty or by sexual indulgence. There is a danger that we may win the war and be unfit to use the victory."

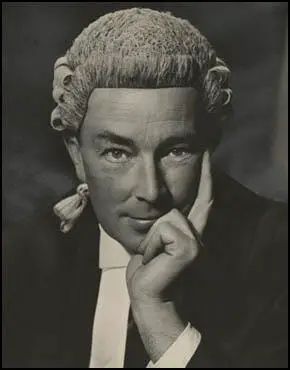

On this day in 2003 Hartley Shawcross, Lord Shawcross of Friston, dies.

Hartley Shawcross was born in Germany on 4th February, 1902. His father, John Shawcross, was professor of English at Frankfurt University. His mother was related to the politician John Bright.

Soon after his birth John and Hilda Shawcross brought their son back to England. Shawcross took an early interest in politics and by the age of 16 he had joined the Labour Party and was ward secretary in Wandsworth. He was also involved in the party's campaign during the 1918 General Election.

A brilliant student, Shawcross decided to study French in Switzerland. While there he became translator to the British delegation at the Socialist International held in Geneva. He met Ramsay MacDonald and Herbert Morrison, who suggested that Shawcross should become a lawyer.

After obtaining a first class honours degree in law he moved to Liverpool. As well as working as a lawyer in the city he also lectured at the University of Liverpool (1927-34). Despite his left-wing views he was willing to work for the coal-owners during the court-case that followed the 1934 Gresford Colliery Disaster. Richard Stafford Cripps represented the miners.

During the Second World War Shawcross chaired the Enemy Aliens Tribunal (1939-41) and Deputy Regional Commissioner for the South-East (1941-42) and Commissioner for the North-West (1942-45).

In the 1945 General Election Shawcross won with a large majority at St. Helens. The new prime minister, Clement Attlee, immediately appointed Shawcross as Britain's Attorney General. In this role he led the British prosecution at Nuremberg.

Shawcross also prosecuted William Joyce for high treason in September, 1945. In court it was stated that although he was United States citizen he had held a British passport during the early stages of the war. It was therefore argued in court by Shawcross that Joyce had committed treason by broadcasting for Nazi Germany between September 1939 and July 1940, when he officially became a German citizen. Joyce was found guilty of treason and was executed on 3rd January 1946.

Other famous prosecutions included the traitor John Amery, the Acid Bath Murderer, John George Haigh and the Atom bomb spy, Klaus Fuchs.

In the House of Commons Shawcross promoted the Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Bill, redressing anti-union legislation (the 1927 Trade Disputes and Trade Union Act) that was passed by a Conservative government following the 1926 General Strike. During the debate on this legislation Shawcross remarked: "We are the masters at the moment, and not only at the moment but for a very long time." He was much attacked for this and later he admitted it "was the most stupid thing I ever said."

In April 1951 Hartley Shawcross was appointed President of the Board of Trade. However, he lost office when the Labour Party lost the 1951 General Election. After this he concentrated on his lucrative law career and eventually retired from the House of Commons in 1958. When he became a life peer later that year he sat on the crossbenches of the House of Lords, although in the 1980s he supported the Social Democratic Party.

In later life Shawcross sat on the boards of a wide variety of different companies including Hawker Siddeley, Shell, EMI, Rank-Hovis-McDougall, Times Newspapers, Dominion Continental Bankers and Thames Television.