Paul Briscoe

Paul Briscoe, the son of Reginald Briscoe, a clerk at the Ministry of Works, and Norah Briscoe, a journalist, was born in Streatham on 12th July 1930. His father died in 1932, following an emergency operation for appendicitis, "leaving a widow who was bitter that he had not taken out life insurance, and resentful that she was encumbered with a son, for whom she felt no affection". (1)

Norah was determined to continue her career as a journalist and employed a nanny to look after Paul: "Beatrice was large, round and deaf, and she spoiled me utterly". More importantly, Beatrice provided him with "the affection, the hugs and kisses his mother refused him". (2)

In 1934 Norah took a holiday in Nazi Germany. She later wrote in her unpublished autobiography: "We seemed to have found in that other land of mountains and streams and towering forests, a corner of the world as remote from war and evil as was possible... You could pray, dance, drink, smoke, and worship as you pleased. Young men in leather breeches leaped over flames on Midsummer Night in a pagan ritual and heard Mass next day. You could follow any creed you liked - provided you followed the Führer, too. And whose business was that but their own?" (3)

On his mother's return to England she joined the PR department of Unilever. One of the tasks she was given was to collect all references to Sir Oswald Mosley, the leader of the National Union of Fascists, that had appeared in all the newspapers owned by Lord Rothermere. She later learned that the cuttings had been requested by some Jewish directors of Unilever. (4)

Norah Briscoe discovered several articles that supported Mosley including an article by Lord Rothermere in The Daily Mail in which he praised Mosley for his "sound, commonsense, Conservative doctrine". Rothermere added: "Timid alarmists all this week have been whimpering that the rapid growth in numbers of the British Blackshirts is preparing the way for a system of rulership by means of steel whips and concentration camps. Very few of these panic-mongers have any personal knowledge of the countries that are already under Blackshirt government. The notion that a permanent reign of terror exists there has been evolved entirely from their own morbid imaginations, fed by sensational propaganda from opponents of the party now in power. As a purely British organization, the Blackshirts will respect those principles of tolerance which are traditional in British politics. They have no prejudice either of class or race. Their recruits are drawn from all social grades and every political party. Young men may join the British Union of Fascists by writing to the Headquarters, King's Road, Chelsea, London, S.W." (5)

Norah Briscoe also found articles that supported Adolf Hitler. As a result of this investigation "Jewish directors of Unilever... decided to present Harmsworth's owner, Lord Rothermere, with an ultimatum: if he did not stop backing Mosley, they and their friends would stop placing advertisements in his papers. Rothermere gave in." However, as Paul pointed out, her investigation involved her "reading almost everything favourable that had been written recently about Mosley and his Blackshirts. What she read, she liked." Norah handed in her notice at Uniliver and decided to become a pro-fascist freelance journalist.

Living in the Nazi Germany

In 1935 Norah Briscoe introduced Paul to Joseph Weyrich (Seppl). "I saw him as an intruder and took an instant dislike to him. I resented this tall, dapper man with a studied smile and big eyes framed by round, black spectacles. I had been used to being the centre of attention and getting my own way... Mother announced that Seppl had invited us to come to Germany, and Seppl told me he would soon make a man of me." (6) Over the next eighteen months they spent living out of a suitcase. (7)

While in Nazi Germany Norah met Molly Hiscox, "a pretty woman in her late twenties who organised German holidays for English Fascist sympathisers". They soon became very close friends. "Neither of us liked the unfair anti-German talk that was increasing in intensity in England... True, Austen Chamberlain had just returned from a visit to announce that Germany was 'one vast arsenal'. What of it? Must they not take proper precautions to protect themselves? But weren't the majority of its inhabitants - and Molly travelled widely in Germany and saw them for herself - enjoying life as they hadn't enjoyed it for many years, with good roads to drive on in their cheap and well made little cars, a freedom from industrial troubles, a decrease in violence, a return to sanity and security, in fact? They were borne on an upsurge of hope and confidence, freed from the long, lingering misery of defeat, we agreed... In the meantime, we listened to the tramp of marching soldiers in the streets at intervals, and found their triumphant songs and happy faces immensely heartening. Here was real joy through strength. We heard no menace in them, nor in the mock air-raids and blacked-out rehearsals that occasionally occurred. The Germans were realists." (8)

In the summer of 1936 Norah returned to England and left Paul with Seppl's parents, Oma and Opa in Miltenberg. (9) Now aged six, Paul attended the local primary school. "Oma had kitted me out in lederhosen, bright braces and stout boots. With my shock of snow-blond hair, I made a convincing little Bavarian - until of course, I opened my mouth to speak... At half-past seven one soft September morning, Oma took me by the hand and led me across the Martplatz and down the lane to the Volksschule. When she left me at the door, I felt physically sick." (10)

The Hitler Youth

Paul Briscoe attended his first Hitler Youth parade in 1936. "The first Hitler Youth parade I saw electrified me. Seppl lifted me onto his shoulders so I could watch it. Behind fluttering banners, rattling side-drums and blaring bugles, row after row of uniformed boys marched past with jutting chins and jaunty caps. I didn't think of them as boys; to me, they looked like gods. When Seppl told me that one day I might be one of them, I could hardly believe him - it seemed too good to be true."

The following year he attended another parade that celebrated Hitler's birthday: "The grandest parade of the year took place in April, on Hitler's birthday. I experienced this first in 1937. The column that marched through the town seemed endless, and each section was led by its own band. We cheered them all, shouting until we were hoarse. Soldiers marching ten abreast were followed by senior and junior sections of the HJ and its female counterpart, the Bund Deutscher Mädel. There was a detachment of the Arbeits Dienst, 18 and 19-year-old men conscripted to do public works projects for a year. They weren't armed, but carried polished ceremonial spades. Then came a fleet of long, low, open-top Mercedes staff cars with swastika pennants on the bonnet, and swastika-armbanded guards on the running boards. The symbol was everywhere: on banners hanging from every window in Miltenberg, and on the little flags that we had all been given to wave." (11)

Paul Briscoe - a German Education

Paul Briscoe was victimized by his teacher at school: "We all hated and feared Herr Göpfert and I probably feared him more than most... Squat, piggy-eyed and frequently Party-uniformed, Herr Göpfert's tools as a teacher were corporal punishment, sarcasm and mockery, and all three were frequently directed at me... He used to keep an empty desk at the front of the class for boys to bend over while being beaten with the cane that he kept clipped under his desk... Like all bullies, once Herr Göpfert found a weakness, he would work away at it. He took every opportunity to remind me that I was not German." (12)

Briscoe later explained in his autobiography, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007), that his school encouraged him to hate Jews: "I knew all about the Jews, of course. I knew what they looked like, because there were drawings of them printed in our textbooks. Jewish men were short and fat, with big lips and bigger noses. They were grandly dressed, but their fine clothes made them look ridiculous because they appeared even shorter and fatter. I knew that they were not - and could never be - real Germans, and that they took advantage of the rest of us in order to get rich, which is why those drawings always showed them carrying sacks of money. I don't remember anyone at home or school ever telling me this with any sense of hatred or urgency; it was just one of those things, a matter of fact. Questions in our maths books would run along the following lines: Herr Goldschmied sells a box of socks for 7.50 marks. Frau Schneider sells a similar box for 6.25 marks. How much more profit does Herr Goldschmied make? In the cinema on Saturday mornings, mind, I saw information films that likened Jews to revolting parasites and rats." (13)

Paul Briscoe now lived with Joseph Weyrich and his girlfriend, Hildegard. Their home was a sprawling apartment above the family's grand furniture shop in Miltenberg's market place. (14) "She (Hildegard) was young, lively, hard-working, generous-spirited and pretty... Whether she was serving customers, helping in the office or working in the sewing room, she always had a smile on her face." Paul became very fond of Hildegard: "When Hildegard took my hand... I felt a happiness that was complete, but I could not understand why. I understand now. I was loved. I was part of a family. I fitted in." (15)

Kristallnacht (Crystal Night)

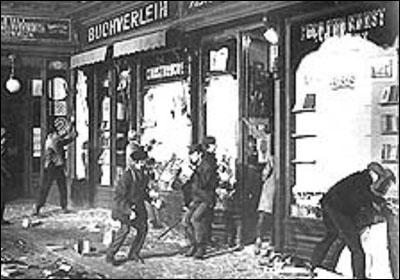

Ernst vom Rath was murdered by Herschel Grynszpan, a young Jewish refugee in Paris on 9th November, 1938. At a meeting of Nazi Party leaders that evening, Joseph Goebbels suggested that night there should be "spontaneous" anti-Jewish riots. (16) Reinhard Heydrich sent urgent guidelines to all police headquarters suggesting how they could start these disturbances. He ordered the destruction of all Jewish places of worship in Germany. Heydrich also gave instructions that the police should not interfere with demonstrations and surrounding buildings must not be damaged when burning synagogues. (17)

Heinrich Mueller, head of the Secret Political Police, sent out an order to all regional and local commanders of the state police: "(i) Operations against Jews, in particular against their synagogues will commence very soon throughout Germany. There must be no interference. However, arrangements should be made, in consultation with the General Police, to prevent looting and other excesses. (ii) Any vital archival material that might be in the synagogues must be secured by the fastest possible means. (iii) Preparations must be made for the arrest of from 20,000 to 30,000 Jews within the Reich. In particular, affluent Jews are to be selected. Further directives will be forthcoming during the course of the night. (iv) Should Jews be found in the possession of weapons during the impending operations the most severe measures must be taken. SS Verfuegungstruppen and general SS may be called in for the overall operations. The State Police must under all circumstances maintain control of the operations by taking appropriate measures." (18)

A large number of young people took part in what became known as Kristallnacht (Crystal Night). (19) Erich Dressler was a member of the Hitler Youth in Berlin. "Of course, following the rise of our new ideology, international Jewry was boiling, with rage and it was perhaps not surprising that, in November, 1938, one of them took his vengeance on a counsellor of the German Legation in Paris. The consequence of this foul murder was a wave of indignation in Germany. Jewish shops were boycotted and smashed and the synagogues, the cradles of the infamous Jewish doctrines, went up in flames. These measures were by no means as spontaneous as they appeared. On the night the murder was announced in Berlin I was busy at our headquarters. Although it was very late the entire leadership staff were there in assembly, the Bann Leader and about two dozen others, of all ranks.... I had no idea what it was all about, and was thrilled to learn that were to go into action that very night. Dressed in civilian clothes we were to demolish the Jewish shops in our district for which we had a list supplied by the Gau headquarters of the NSKK, who were also in civilian clothes. We were to concentrate on the shops. Cases of serious resistance on the part of the Jews were to be dealt with by the SA men who would also attend to the synagogues." (20)

Paul Briscoe was in bed when he first heard the riots taking place in Miltenberg: "At first, I thought I was dreaming, but then the rhythmic, rumbling roar that had been growing inside my head became too loud to be contained by sleep. I sat up to break its hold, but the noise got louder still. There was something monstrous outside my bedroom window. I was only eight years old, and I was afraid. It was the sound of voices - shouting, ranting, chanting. I couldn't make out the words, but the hatred in the tone was unmistakable. There was also - and this puzzled me - excitement. For all my fear, I was drawn across the room to the window. I made a crack in the curtains and peered out. Below me, the triangular medieval marketplace had been flooded by a sea of heads, and flames were bobbing and floating between the caps and hats. The mob had come to Miltenberg, carrying firebrands, cudgels and sticks."

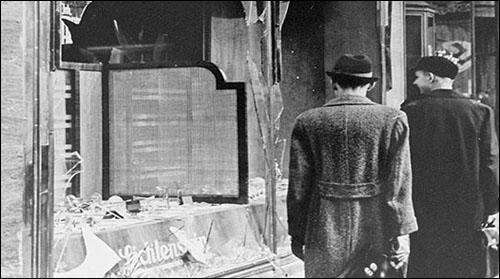

Paul Briscoe could hear the crowd chanting "Jews out! Jews out!" In his autobiography, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) Briscoe recalled: "I didn't understand it. The shop was owned by Mira. Everybody in Miltenberg knew her. Mira wasn't a Jew, she was a person. She was Jewish, yes, but not like the Jews. They were dirty, subhuman, money-grubbing parasites - every schoolboy knew that - but Mira was - well, Mira: a little old woman who was polite and friendly if you spoke to her, but generally kept herself to herself. But the crowd didn't seem to know this: they must be outsiders. Nobody in Miltenberg could possibly have made such a mistake. I was frightened for her.... A crash rang out. Someone had put a brick through her shop window. The top half of the pane hung for a moment, like a jagged guillotine, then fell to the pavement below. The crowd roared its approval." (21)

Attack on Miltenberg Synagogue

The following day Paul Briscoe was told by his teacher that the day's lessons had been cancelled and that they had to attend a meeting in the town: "Whatever was going to happen must have been planned well in advance, for the streets were lined with Brownshirts and Party officials, and the boys from the senior school were assembled in the uniform of the Hitler Youth. A festival atmosphere filled the town. Party flags, red, black and white, hung from first-floor windows, fluttering and snapping in the breeze - just as they did during the Führer's birthday celebrations each April. But there was something angry and threatening in the air, too."

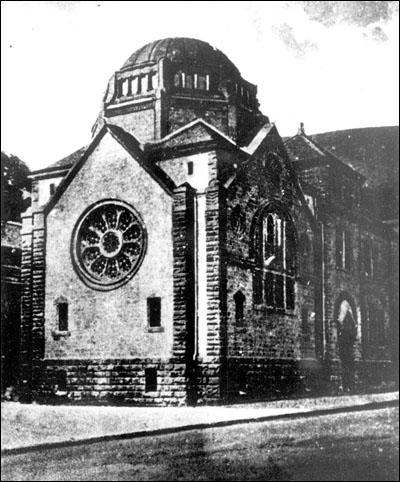

The boys were then marched to Miltenberg's small synagogue. "We all stood there staring at it while we waited to find out what was to happen next. For a long moment, nobody moved and all was quiet. Then, another command was shouted - I was too far back to make out the words - and the boys at the front broke ranks, flying at the synagogue entrance, cheering as they ran. When they reached the door, they clambered over each other to beat on it with their fists. I don't know whether they broke the lock or found a key, but suddenly another cheer went up as the door opened and the big boys rushed in. We youngsters stood still and silent, not knowing what to expect."

Herr Göpfert ordered Briscoe and the other young boys to go into the synagogue: "Inside was a scene of hysteria. Some of the seniors were on the balcony, tearing up books and throwing the pages in the air, where they drifted to the ground like leaves sinking through water. A group of them had got hold of a banister rail and kept rocking it back and forth until it broke. When it came away, they flung the spindles at the chandelier that hung over the centre of the room. Clusters of crystal fell to the floor. I stood there, transfixed by shock and disbelief. What they were doing was wrong: why weren't the adults telling them to stop? And then it happened. A book thrown from the balcony landed at my feet. Without thinking, I picked it up and hurled it back. I was no longer an outsider looking on. I joined in, abandoning myself completely to my excitement. We all did. When we had broken all the chairs and benches into pieces, we picked up the pieces and smashed them, too. We cheered as a tall boy kicked the bottom panel of a door to splinters; a moment later, he appeared wearing a shawl and carrying a scroll. He clambered up to the edge of the unbanistered balcony, and began to make howling noises in mockery of Jewish prayers. We added our howls to his."

Briscoe then described what happened next: "As our laughter subsided, we noticed that someone had come in through a side door and was watching us. It was the rabbi: a real, live Jew, just like the ones in our school textbooks. He was an old, small, weak-looking man with a long dark coat and black hat. His beard was black, too, but his face was white with terror. Every eye in the room turned to him. He opened his mouth to speak, but before the words came, the first thrown book had knocked his hat off. We drove him out through the main door where he had to run the gauntlet of the adults outside. Through the frame of the doorway I saw fists and sticks flailing down. It was like watching a film at the cinema, but being in the film at the same time. I caught close ups of several of the faces that made up the mob. They were the faces of men that I saw every Sunday, courteously lifting their hats to each other as they filed into church." (22)

British Union of Fascists

While living in London, Paul's mother, Norah Briscoe, became a supporter of Sir Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists. Her son later wrote that "The fascist cause became an obsession. She talked of little else. The Jews were parasites conspiring to destroy western civilisation and engineering a war that had to be stopped... Mother had found a flag that offered her the recognition she felt was hers by right and which had been denied her by her family and by society." (23)

During this period Nora became friends with Dr Leigh Vaughan-Henry, the head of the National Citizens' Union. "Mother formed a particular admiration for Vaughan-Henry, who was the most educated and urbane person she had ever met. Eloquent and softly spoken in German, French and Italian as well as English, he was a poet and a composer, though his poems and compositions had brought him little recognition or fame... Like Mother, he saw himself as a frustrated artist. Fascism gave him a voice. He wrote about national culture for The Blackshirt and gave talks about music on German radio." (24)

In 1939 Vaughan-Henry wrote to Emil Van Loo, a leading fascist in the Netherlands: "This is to introduce you to a journalist friend and author, Mrs Briscoe... I think this would be a good opportunity for her to discuss with you your New Economic Order movement in Holland, especially as she is politically well-informed and ties up her interests in contemporary international matters to that in cultural developments, seen as components of the social and political whole. She is quite Jew-wise and aware of much of the machinations which are worked by international finance. You may find her views proceed further in the direction of totalitarianism than your own, as do my own ideas, as you are well aware." (25)

The Second World War

The German Army invaded Czechoslovakia on 15th March 1939. "When we were not learning what to feel guilty about in our R.E. lessons, we were learning about things to be proud of in the newsreels we watched on Saturday mornings. In March, we saw footage of German troops marching into Prague to occupy what was left of Czechoslovakia, which was now to be called the Bohmen and Mahren Protectorate. In our geography lessons we were told that the lands had been part of Germany's living space for the last thousand years, and that the occupation was necessary for our national security. A set of commemorative stamps was issued, and we were encouraged to show our support for the Führer by buying them. They cost all my pocket money, but it was worth it. When I stuck them in my album, I felt proud to have done something so selflessly patriotic and good." (23)

After the outbreak of the Second World War Paul's mother, Norah Briscoe, was unable to visit him. According to her autobiography, she was not too concerned about his safety: "I never doubted that I would see the child again, nor feared for his welfare in the enemy's land, but lived on an optimism which was a kind of sixth sense." (24)

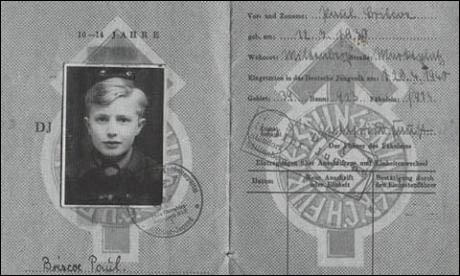

Paul was now stranded in Germany for the duration of the war, and his German family adopted him to spare him internment. "The war gave me a perfect opportunity to demonstrate my loyalty to the nation and the family that had accepted me." He later claimed that when he swore the oath of allegiance to the Führer. "I would have carved those words in my heart if they had asked me to." (25)

Nora Briscoe - Nazi Spy

Back in London, Norah Briscoe and Molly Hiscox became involved in the secret Right Club. It was established by Archibald Ramsay, the Conservative MP for Peebles and Southern Midlothian, in May 1939. The Daily Worker described Ramsay "Britain's Number One Jew Baiter". (26) This was an attempt to unify all the different right-wing groups in Britain. Or in the leader's words of "co-ordinating the work of all the patriotic societies". In his autobiography, The Nameless War, Ramsay argued: "The main object of the Right Club was to oppose and expose the activities of Organized Jewry, in the light of the evidence which came into my possession in 1938. Our first objective was to clear the Conservative Party of Jewish influence, and the character of our membership and meetings were strictly in keeping with this objective."(27)

Unknown to Ramsay and Briscoe, MI5 agents had infiltrated the Right Club. This included three women, Joan Miller, Marjorie Amor and Helem de Munck. The British government was therefore kept fully informed about the activities of Ramsay and his right-wing friends. Soon after the outbreak of the Second World War the government passed a Defence Regulation Order. This legislation gave the Home Secretary the right to imprison without trial anybody he believed likely to "endanger the safety of the realm" On 22nd September, 1939, Oliver C. Gilbert and Victor Rowe, became the first members of the Right Club to be arrested. In the House of Commons Ramsay attacked this legislation and on 14th December, 1939, asked: "Is this not the first time for a very long time in British history, that British born subjects have been denied every facility for justice?" (28)

Anna Wolkoff, a member of the Right Club, and Tyler Kent, a cypher clerk from the American Embassy, were arrested and charged under the Official Secrets Act. The trial took place in secret and on 7th November 1940, Wolkoff was sentenced to ten years. Kent, because he was an American citizen, was treated less harshly and received only seven years. Archibald Ramsay was surprisingly not charged with spying. Instead he was interned under Defence Regulation 18B. (29)

The New York Times reported: "Here was a man who was known to a wide circle of friends, many of whom seemed to be no better than himself, to be grossly disloyal to this country, and to be an associate, as he was, of thieves and felons now convicted. Captain Ramsay's whole picture of himself was of a loyal British gentleman, with sons in the Army, doing his best to help this country to win a victory in her life-and-death struggle. Captain Ramsay was, however, a man of no character and no reputation, and was perhaps very lucky only to be detained under the Defence Regulations." (30)

Norah Bruce was brought to the attention of the police when they received an anonymous letter: "Please investigate the right of a certain Mrs Briscoe to be in the Ministry of Information office. The woman has always been a Nazi propagandist, has a large circle of German friends and is to the best of my knowledge married to a German. She has a son by her first husband being educated as a German in Germany. I'm sorry I cannot sign my name as I'm afraid she may do some harm to my friends." (31)

This information was passed on to MI5. They kept a close watch on her activities. On 20th January 1941, Norah took a job as a typist in the Ministry of Supply. On 19th February she was promoted to the Central Priority Department. Most of its work was confidential and much of it secret. (32) Norah was now typing up sensitive documents about submarine bases and the shortage of spare parts. Apparently, she told a friend, "I get sight of such important official documents. When I come across a really hot one, I make a carbon copy and keep it in a folder in my desk." (33)

Norah joined forces with Molly Hiscox to get these documents to Nazi Germany. Molly put her in touch with one of her associates at the Right Club, a man in his twenties who was known to her as John. It has been suggested that this man was really Ferdinand Mayer-Horckel, a German-Jewish refugee. He in turn introduced her to a man named Harald Kurtz. Both men were in fact MI5 agents. (34)

Guy Liddell, director of counter-espionage at MI5, wrote in his diary that he had a meeting with Major Charles Maxwell Knight, head of counter-subversion unit B5(b): "The Norah Briscoe case is developing. M (Charles Maxwell Knight) is introducing a German agent and there is to be a meeting when he will get the documents. This case was first brought to my notice on Saturday. One of M's agents was asked to tea with Molly Hiscox, where he met Norah Briscoe, who is the wife or mistress of Jock Houston, the interned member of the BUF Briscoe said that she was working in quite an important section of the Ministry of Supply and that she had been copying all documents which she thought would be of interest. She is of German origin and has a son who is being brought up in Germany. She is now looking for some means of getting the documents through to the Germans." (35)

At meeting was arranged at a flat in Chelsea, Norah Briscoe handed over to Kurtz a collection of secret documents from the Ministry of Supply. Maxwell Knight and two members of Special Branch were in the next room and a few moments later they arrested the two women. (36) Briscoe and Hiscox appeared before the magistrate on 17th March 1941 on charges under the Treachery Act (1940). They were convicted and sentenced to five years penal servitude at the Central Criminal Court on 16th June 1941. (37)

After the case Liddell recorded in his diary: "Lunched with M. He told me all about the Briscoe case and showed me the documents. They are voluminous and cover a wide field. If the information had leaked it would certainly be a very serious matter. They relate to the location of factories, shortage of materials, establishment of submarine bases in Northern Ireland, etc. (38)

Defeat of Nazi Germany

Paul Briscoe was shocked when he heard a special announcement on the radio at the beginning of February 1943 about the Battle of Stalingrad: "The Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht announces that the battle of Stalingrad has come to an end. True to its oath of allegiance, the Sixth Army under the exemplary leadership of Field Marshal Paulus has been annihilated by the over-whelming superiority of enemy numbers... They died so that Germany might live." (39)

He later explained that all the reports he had heard in the last six months from the Eastern Front had been of victories. Briscoe was aware that there were a quarter of a million men in the Sixth Army and found it difficult to believe so many men were killed. In fact, around 91,000 had disobeyed orders and surrendered to the Red Army. "Three days of national mourning were declared, during which all radio broadcasts were to be replaced by solemn music". (40)

Joseph Weyrich's family had become very critical of Adolf Hitler. Paul Briscoe was such a loyal follower of the Nazi government he considered reporting them to the authorities: "I shuddered to hear anyone speak like that about our Führer. I didn't know what to think. I was a loyal member of the Hitler Youth. We had been told that it was our duty to report any dissenting voices or doubters, but I couldn't possibly denounce my own family - though I knew that some of the other boys had denounced theirs. Such talk upset me. It was treacherous. But I said nothing." (41)

Life became very difficult for Paul Briscoe. Miltenberg was often a target of Allied air attacks. A train he was on to school was strafed with bullets by an American fighter plane. Another bomb fell close to his house when he was collecting wood. He escaped with a badly damaged hand. (42)

Briscoe's school in Miltenberg was by 1944 very overcrowded. "The classes were bigger, and numbers were constantly increased by refugees. Many of these were Volksdeutsche, ethnic Germans who had settled in places as far away as the Black Sea, and who were now returning to the bosom of the fast-shrinking Reich. The teachers were all old and seemed to have been dragged unwillingly from retirement. There were never enough of them, and some classes contained as many as a hundred pupils. The education system was collapsing under the weight of a war that we were obviously losing, and there wasn't much learning going on." (43)

Paul Briscoe was an active member of the Hitler Youth: "Discipline was tough, but there was a sense of camaraderie and common purpose. I let the political lecturing go over my head - I suspect we all did - but in every practical sense, I joined in. The reward was a warm sense of belonging. We were building a new Germany, and I was part of it." Desperately short of labour, they used the boys as cheap labour. In 1944 his unit was sent to Au, with the local German Girls' League (BDM) to help with the hop harvest.

"We would stay there for a fortnight. We were to travel in uniform, taking a second set of clothes in which to work. We would work eight hours a day, Saturdays included. The BDM girls would join us in the fields when they were not cooking or washing. On Sundays we would be free to attend meetings, and then rest. Tools, baskets and stools would be provided.... We broke into song as the train pulled out. We felt like heroes and holidaymakers both at once. The journey took all day, because we took a cross-country route, collecting carriages of other youngsters at various stations. When we finally got to Au, our engine whistle seemed to sound a note of joy mixed with relief. We had lots of fun that fortnight, but it wasn't quite the treat we had expected. The beer turned out to be Nahrbier with very little alcohol in it, and I worked so hard that I was too tired even to think about sex. If any of the other boys and girls managed to get up to anything like that, I didn't notice. The work was tough, but it was happy and purposeful." (44)

At the end of 1944 he joined the team of old men and boys and girls that made up Miltenberg's auxiliary fire service. However, he never got the chance of putting out a fire as a few months later American troops arrived in the town. (45) "Miltenberg was suddenly full of uniforms, and most of the soldiers wearing them were black. We had been conquered by men whom we had been taught to consider our inferiors. We could see from the way that their white officers spoke to them that they thought them inferior, too... As if that were not enough of a sign that our world had been turned upside down, the occupying Americans established their headquarters in the boarded-up Miltenberg synagogue." (46)

Return to England

In October 1945 a British Army officer appeared at the door of Briscoe's adoptive family and announced that he had half an hour to pack: he was going "home" to a country "whose language he had long forgotten and to a mother he had not heard from for four years". (47) At first he refused to go: "I thought of Hildegard as my mother, and with Seppl gone, it was my duty to look after her." (48)

Norah Briscoe was released from Holloway Prison in the summer of 1945 and was able to meet him when he arrived at Croydon Airport. (49) She was living with Molly Hiscox and Richard Houston in South Norwood. "I never met anyone so full of himself... Mother and Molly were obviously in awe of him... I felt no affection for the Mother that had reclaimed me, but I could see that she was genuinely proud of me. I was grateful for that." (50)

Paul often had to listen to the political rants of Houston and resisted his attempts to get him to read the racist, The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion. This only increased his guilt over the way he had behaved in Nazi Germany: "Yes, I had my excuses: I was young; I was taught these things by my teachers; and when I asked what was happening to the Jews, I accepted what I was told by my family- that it was none of my business. But I should have made it my business. I began to be haunted by the memory of the part I had played in the desecration of the Miltenberg synagogue. I had known what I was doing was wrong, and I had enjoyed it. Meanwhile, Mother's anti-Semitism simply evaporated. She listened politely enough to Jock's Jew rants, but I never heard her join in or concur, and I never heard her utter an anti-Semitic remark." (51)

In 1946 Norah began working for John Middleton Murry, the literary critic and editor of the journal, Peace News. Norah and Paul went to live with Murry at Lodge Farm, Thelnetham, Suffolk. (52) Paul enjoyed his time with Murry on his commune but his mother decided to leave in 1947 to take up a new post as assistant matron in a Land Army hostel. "It was strange how difficult we renegades found it to confront the mild, gentle man, and the puzzled, sadly accusing eyes, to tell him the unpalatable truth: that his free society felt remarkably like a prison to us, from which we must escape or die." (53)

In 1948 Norah Briscoe's novel, No Complaints in Hell was published. The book, which was based about her experiences in prison, It received mixed reviews: "Most praised its realistic description of prison life, but described the characterization as functional and flat." Paul believed that the novel was deeply flawed because although she "was beginning to understand other people, she had not yet learned to understand herself." (54)

While staying with John Middleton Murry Paul had become a pacifist. However, his attempt to plea conscientious objection in 1949 was rejected and had to do his National Service. (55) He was sent to Germany where his knowledge of the language was put to good use: "I was assigned to Field Security, put in civilian clothes and sent to listen in on political meetings. I wasn't any better at spying than Mother. I was identified as a foreigner at a gathering of old Party comrades in Bad Harzburg and was lucky to get away before I was lynched. The same thing happened at a Communist rally in Hamburg, when I was rescued by being bundled into a jeep by the Military Police." (56)

After demobilisation he repaired historic buildings for the Ministry of Works. In 1956 he married Monica Larter, an infant schoolteacher. Inspired by his wife's profession he did a two-year teacher training course and in 1960 he began teaching woodwork in a secondary modern school in Essex. He later taught German in a schools in Suffolk. (57)

Monica gave birth two children, Catherine and Robert. Norah Briscoe, who was now suffering from Bell's Palsy, moved in with the family. "She stayed with us for the last thirty years of her life, living contentedly on the edge of our family and social circles, becoming known and liked as a spirited, independent-minded character who travelled the countryside on her bicycle until well into her eighties. She loved telling our children and our visitors stories of her life and adventures, but she never spoke of her crime or its punishment, and she fell silent whenever anyone mentioned the war." (58)

In 1993 Norah Briscoe suffered a series of minor strokes that left her needing constant nursing care and was placed in a home near Saxmundham: "Monica and I visited her almost daily,but visits were difficult: she suffered frequent hallucinations, and would talk about strange things that only she could see... After a few months of this, she had another stroke that robbed her of the power of speech. At first, she was distressed and frustrated, but after only a few days, she seemed to accept her condition andput up with it bravely." (59)

Norah died in 1997. His foster mother, Hildegard, became seriously ill in 1999: "I visited her a couple of weeks before her death. She had spent several years in a nursing home run by nuns in Miltenberg. When I telephoned to say I was coming, they warned me not to expect too much. She was bedridden, paralysed and unable to understand orcommunicate. She had been like that for some months. She wouldn't recognise me. It broke my heart to see her lying there, her body tidily arranged by another's hands, like a laid-out corpse. Her head was propped up slightly, facing the door. Her eyes were open, but dull and sightless... Hildegard, I said - but she showed no sign of hearing. Hildegard - dein Paulchen ist hier. And a large tear formed in the corner of her eye, rolled down her cheek and fell to stain the starched white pillowcase below." (60)

Briscoe was a gifted raconteur, and delivered many talks about his experiences to audiences in Britain and Germany. He wrote two autobiographical memoirs, Foster Fatherland (2002) and My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007). "In each, he presented a child's-eye view of the hopes, fears and disappointments of an ordinary German family as the war progressed. He described in detail the increasing privations of everyday life as the Reich began to crumble, including a visit to the dentist in which his tooth was stopped with melted-down coins. He recorded how Nazi propaganda poisoned every aspect of the school curriculum: his maths books taught subtraction by asking how much more profit was made by the Jew who charged more for his goods than the Aryan; his history lessons listed the evils of the British Empire. He was taught to think of the English as his enemy." (61)

Paul Briscoe died on 15th August, 2010.

Primary Sources

(1) Norah Briscoe, Daemons and Magnets (unpublished)

Neither of us liked the unfair anti-German talk that was increasing in intensity in England... True, Austen Chamberlain had just returned from a visit to announce that Germany was "one vast arsenal". What of it? Must they not take proper precautions to protect themselves? But weren't the majority of its inhabitants - and Molly travelled widely in Germany and saw them for herself - enjoying life as they hadn't enjoyed it for many years, with good roads to drive on in their cheap and wellmade little cars, a freedom from industrial troubles, a decrease in violence, a return to sanity and security, in fact? They were borne on an upsurge of hope and confidence, freed from the long, lingering misery of defeat, we agreed.

We had to admit that the women's clothes were a trifle behind the times, that people's mobility was strictly controlled, and that freedom as we had been trained to understand it was certainly lacking; but these things were part of the birth pangs, and would improve as the economy became stable, and full stature was regained...

In the meantime, we listened to the tramp of marching soldiers in the streets at intervals, and found their triumphant songs and happy faces immensely heartening. Here was real joy through strength. We heard no menace in them, nor in the mock air-raids and blacked-out rehearsals that occasionally occurred. The Germans were realists.

An encounter with the Gestapo, no less, gave me one more proof of the perfidy of the detractors. The two men who called for me were insignificant looking enough. Only Frau B (landlady) flurried manner and anxious eyes as she ushered me into their presence warned me that they were not as they seemed; and the swift turning back of the jacket lapels gave the final theatrical touch. Neither could speak English, nor could their chief, to whose bureau they accompanied me on foot. Whether I got anything across in my execrable German of my admiration for their country, I don't know. At all events, the handsome man with the grey, clipped moustache, appraising me from behind his desk, had soon had enough of me, abruptly shook my hand, and had me taken away, not to an extermination camp, but out into the street and freedom.

(2) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007)

The first Hitler Youth parade I saw electrified me. Seppl lifted me onto his shoulders so I could watch it. Behind fluttering banners, rattling side-drums and blaring bugles, row after row of uniformed boys marched past with jutting chins and jaunty caps. I didn't think of them as boys; to me, they looked like gods. When Seppl told me that one day I might be one of them, I could hardly believe him - it seemed too good to be true.

The grandest parade of the year took place in April, on Hitler's birthday. I experienced this first in 1937. The column that marched through the town seemed endless, and each section was led by its own band. We cheered them all, shouting until we were hoarse. Soldiers marching ten abreast were followed by senior and junior sections of the HJ and its female counterpart, the Bund Deutscher Mddel. There was a detachment of the Arbeits Dienst, 18 and 19-year-old men conscripted to do public works projects for a year. They weren't armed, but carried polished ceremonial spades. Then came a fleet of long, low, open-top Mercedes staff cars with swastika pennants on the bonnet, and swastika-armbanded guards on the running boards. The symbol was everywhere: on banners hanging from every window in Miltenberg, and on the little flags that we had all been given to wave.

I didn't see those red, black and white flags as symbols of Nazism; I saw them as the symbol of the nation (which indeed they had been since September 1935). Nor did I think of those occasions on which we waved them as political events; to my childish imagination, they seemed like celebrations of life. Germans were rejoicing at being Germans - that was what they did. And that was what I wanted to do, too.

(3) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007)

I knew all about the Jews, of course. I knew what they looked like, because there were drawings of them printed in our textbooks. Jewish men were short and fat, with big lips and bigger noses. They were grandly dressed, but their fine clothes made them look ridiculous because they appeared even shorter and fatter. I knew that they were not - and could never be - real Germans, and that they took advantage of the rest of us in order to get rich, which is why those drawings always showed them carrying sacks of money. I don't remember anyone at home or school ever telling me this with any sense of hatred or urgency; it was just one of those things, a matter of fact. Questions in our maths books would run along the following lines: Herr Goldschmied sells a box of socks for 7.50 marks. Frau Schneider sells a similar box for 6.25 marks. How much more profit does Herr Goldschmied make? In the cinema on Saturday mornings, mind, I saw information films that likened Jews to revolting parasites and rats.... I didn't know any Jews personally. There weren't any at school. Oma once told me that Mira, the old woman who ran the haberdashery on the other side of the Marktplatz, was a Jewess, but she said this to pass on a fact, not to inspire hate. I never heard anyone at home actively criticise the Jews. But they didn't actively criticise the way the Jews were treated, either. Since the Nazis that Mother so admired had come to power in 1933, they had made life for the Jews in Germany increasingly difficult. Jews were not allowed to be employed as civil servants of any sort. Marriage and sexual relations between 'Aryans' and Jews were punishable by law.

(4) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007)

At first, I thought I was dreaming, but then the rhythmic, rumbling roar that had been growing inside my head became too loud to be contained by sleep. I sat up to break its hold, but the noise got louder still. There was something monstrous outside my bedroom window. I was only eight years old, and I was afraid.

It was the sound of voices - shouting, ranting, chanting. I couldn't make out the words, but the hatred in the tone was unmistakable. There was also - and this puzzled me - excitement. For all my fear, I was drawn across the room to the window. I made a crack in the curtains and peered out. Below me, the triangular medieval marketplace had been flooded by a sea of heads, and flames were bobbing and floating between the caps and hats. The mob had come to Miltenberg, carrying firebrands, cudgels and sticks.

The rage of the crowd was directed at the small haberdasher's shop on the opposite side of the marketplace. Nobody was looking my way, so I dared to open the window a little, just enough to hear what all the shouting was about.

The words rushed in on the cold, late autumn air. "Ju-den raus! Ju-den raus!" - "Jews out! Jews out!"

I didn't understand it. The shop was owned by Mira. Everybody in Miltenberg knew her. Mira wasn't a Jew, she was

a person. She was Jewish, yes, but not like the Jews. They were dirty, subhuman, money-grubbing parasites - every schoolboy knew that - but Mira was - well, Mira: a little old woman who was polite and friendly if you spoke to her, but generally kept herself to herself. But the crowd didn't seem to know this: they must be outsiders. Nobody in Miltenberg could possibly have made such a mistake. I was frightened for her. The mob was yelling for her to come out, calling her "Jew-girl" and "pig" - "Raus, du Judin, raus, du Schwein!" - but I was willing her to stay put, to hide, to wait for them to go away: No, Mira, don't come out, don't listen to them, please...A crash rang out. Someone had put a brick through her shop window. The top half of the pane hung for a moment, like a jagged guillotine, then fell to the pavement below. The crowd roared its approval, but the roar subsided as people began to nudge and point. Three storeys above them, a window was opened, and a pale, frightened face looked out. The window was level with mine, and I could see Mira very clearly. Her eyes were dark, like glistening currants.

The mob fell silent to let her speak, and her thin voice trembled over their heads. "Was ist los? Warum all das?" - "What's going on? What's all this about?" But it was clear that she knew. A man in the crowd mimicked her in mocking falsetto, and the Marktplatz echoed with cruel laughter. Another voice yelled, "Raus, raus, raus!" and the cry was picked up and quickly became a chant. The call was irresistible. Soon, Mira was standing in the wrecked doorway of her shop, among the ribbons, reels and rolls of cloth that lay scattered among the broken glass. She was wearing a long white nightdress. The wind caught it, and it ballooned about her. Then she was gone, lost in the crowd, which moved off along the Hauptstrasse towards the middle of the town. Behind them, the marketplace filled with dark.

(5) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007)

When we were not learning what to feel guilty about in our R.E. lessons, we were learning about things to be proud of in the newsreels we watched on Saturday mornings. In March, we saw footage of German troops marching into Prague to occupy what was left of Czechoslovakia, which was now to be called the Bohmen and Mahren Protectorate. In our geography lessons we were told that the lands had been part of Germany's living space for the last thousand years, and that the occupation was necessary for our national security. A set of commemorative stamps was issued, and we were encouraged to show our support for the Führer by buying them. They cost all my pocket money, but it was worth it. When I stuck them in my album, I felt proud to have done something so selflessly patriotic and good.

(6) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007)

I threw myself into Hitler Youth (HJ) life with enthusiasm. Discipline was tough, but there was a sense of camaraderie and common purpose. I let the political lecturing go over my head - I suspect we all did - but in every practical sense, I joined in. The reward was a warm sense of belonging. We were building a new Germany, and I was part of it. My unit was a branch of the HJ's naval section. We wore a naval uniform: a top with a striped collar, bell-bottomed trousers, and a sailor's cap with two blue ribbons hanging from the back and Marine Hitler Jugend printed on a band on the front. My brass belt buckle had an anchor on it, and I would polish it until it gleamed. We were miles from the sea, of course, but we had the River Main on our doorstep. We were taught how to row, how to send signals by Morse code and semaphore, and how to knot and splice ropes.

Shortly after I joined, one of our meetings was addressed by a Party official who told us that we were to be going off on a very un-naval adventure. We and all the other units in our Gau were to help with the hop harvest. The BDM girls would be going, too. At first I thought he was asking for volunteers, but it was soon clear that we were all going whether we wanted to or not. We stood to attention as he read us our marching orders from a piece of paper. Everything had been planned down to the last detail.

We were being sent to Au, a small town north of Munich. We would stay there for a fortnight. We were to travel in uniform, taking a second set of clothes in which to work. We would work eight hours a day, Saturdays included. The BDM girls would join us in the fields when they were not cooking or washing. On Sundays we would be free to attend meetings, and then rest. Tools, baskets and stools would be provided. Bed spaces and sleeping areas were to be inspected daily. We would be paid generously and allowed to keep a small amount of our pay as pocket money; we would donate the rest to the Red Cross who looked after our brave soldiers, and to Winterhilfe (Winter Aid) to buy blankets and warm clothes for the needy. The band was to take its instruments. First-aid kits would be provided. We would be given a beer ration of a litre a day.

None of us moved or spoke, but we could all sense each other's excitement. The whole thing sounded like a marvellous adventure: a fortnight away from home with all those girls and beer, too - it had to be too good to be true! On the appointed day, we all marched behind our band and flags to the station. Oma and Hildegard were among the crowd of parents that waved us off. We broke into song as the train pulled out. We felt like heroes and holidaymakers both at once. The journey took all day, because we took a crosscountry route, collecting carriages of other youngsters at various stations. When we finally got to Au, our engine whistle seemed to sound a note of joy mixed with relief.

We had lots of fun that fortnight, but it wasn't quite the treat we had expected. The beer turned out to be Nahrbier with very little alcohol in it, and I worked so hard that I was too tired even to think about sex. If any of the other boys and girls managed to get up to anything like that, I didn't notice. The work was tough, but it was happy and purposeful.

(7) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007)

Yes, I had my excuses: I was young; I was taught these things by my teachers; and when I asked what was happening to the Jews, I accepted what I was told by my family- that it was none of my business. But I should have made it my business. I began to be haunted by the memory of the part I had played in the desecration of the Miltenberg synagogue. I had known what I was doing was wrong, and I had enjoyed it.

Meanwhile, Mother's anti-Semitism simply evaporated. She listened politely enough to Jock's Jew rants, but I never heard her join in or concur, and I never heard her utter an anti-Semitic remark. At the time, I thought nothing of it, because I didn't then know of her reputation as an extremist among extremists. Today, I find myself wondering how her obsession could have been so easily forgotten. I can only guess, because she never talked about it. I suspect that it simply ceased to matter. Now that she was a published novelist, she had the recognition that she had craved.

She didn't need the world to be turned on its head so that it would accept her as a person of importance. The idea that there was an international Jewish conspiracy to keep good people down had become irrelevant, because she no longer needed anyone to blame for her failure, now that she saw herself as a success.

My bid for conscientious objection was rejected, and I did two years' National Service - in Germany, where my knowledge of the language was put to good use. I was assigned to Field Security, put in civilian clothes and sent to listen in on political meetings. I wasn't any better at spying than Mother. I was identified as a foreigner at a gathering of old Party comrades in Bad Harzburg and was lucky to get away before I was lynched. The same thing happened at a Communist rally in Hamburg, when I was rescued by being bundled into a jeep by the Military Police.

(8) The Daily Mail (21st April, 2007)

On November 9 and 10 1938, when Jewish homes, shops and synagogues were wrecked in an outpouring of anti-Semitism orchestrated by the Nazi party, one unlikely participant in the pogrom was an eight-year-old English boy, who was living in the Bavarian town of Miltenberg.

Feeling very much the foreigner, and anxious to be accepted, Paul Briscoe followed the instructions of his teachers and joined in the trashing of the local synagogue with gusto. He and his classmates smashed all the furniture in the building, and pelted the rabbi with his own books.

Briscoe felt himself to be an outsider, but he did not look like one: he was blond-haired, blue-eyed and fine-featured - the very embodiment of the Nazi racial stereotype. When scenes for a propaganda film were being shot in Miltenberg that year, the director pulled him out of the crowd that had gathered to watch, and invited him to play a walk-on part.

Not many of those who saw Spiel im Sommerwind knew that the very Nordic-looking boy running around the town's fountain was English; fewer still knew how he came to be living in a country with which England was soon to be at war.

Aged ten, Paul Briscoe swore to devote all his energy and strength to Hitler.

"And I meant it. I would have carved those words in my heart if they asked me to. I was keen to show myself to be as anti-British as the rest," says Mr Briscoe....

Paul also now had a new 'mother'. Hildegard, whom Seppl had met after Norah could no longer visit Germany, had no reason to take on the son of his exgirlfriend, but she did.

There was even talk of formal adoption. "She hugged me and I cried tears of joy. For the first time in my life, someone had told me I was loved."

Sporadic letters arrived from his mother via the Red Cross. He replied, struggling to fill the 25-word space allowed.

"It was like writing to a stranger. I hadn't seen her for two years. I couldn't remember what her voice sounded like."

For a small boy, life in that town on the banks of the river Main, nestling beneath a castle and with forest and mountain behind, was untroubled at first. The bombs were falling elsewhere. He never heard the name 'Auschwitz' or 'Buchenwald'.He noticed that the few Jews he once knew had disappeared, but when he raised the matter conversationally with Oma and Opa they changed the subject. "It's none of our business."

Things got tougher as the war went on. Food was rationed and a train he was on to school was strafed with bullets by an American fighter plane. Refugees arrived, and wounded soldiers.

It was a tradition in the Hitler Youth to salute war veterans and he did so. One who had lost both arms just stared back at him.

In the Sauter household there were mutterings about Hitler. He was a Dummkopf, said Oma. Ironically, it was the English boy who remained loyal and swore to give his last drop of blood for the Fatherland.

A bomb that fell in a yard as he queued for wood almost gave him his wish. He escaped with a badly damaged hand.

As the Third Reich faced its end, American tanks appeared outside Miltenberg. A dozen shells whistled overhead - warning shots.The mayor surrendered, and Paul Briscoe's strange war ended in what he could only see as defeat. The country and the people who had rescued him from his mother's indifference had lost.

An English Army captain came for the 15-year-old. "He had orders to take me home - 'to England, to your mother'. I told him I didn't want to go. I loved my Fatherland and my foster family."

He couldn't even speak his native language any more. "I had forgotten all but a half-dozen words of English."

But he had to go, leaving behind Oma, Opa and Hildegard. "Auf Wiedersehen, Paulchen", he heard them calling as he was driven away.

(9) The Daily Telegraph (20th August, 2010)

Paul Briscoe was born in Streatham, south-west London, on July 12 1930. His mother, born Norah Davies, was a journalist with literary and social ambitions; his father, Reginald Briscoe, was a clerk at the Ministry of Works.

Reginald died in 1932, leaving a widow who was bitter that he had not taken out life insurance, and resentful that she was encumbered with a son, for whom she felt no affection. A nanny looked after Paul while his mother attempted to rebuild her career.

When Norah Briscoe took a holiday in Hitler's Germany in 1934, she fell in love with the country and with a German she met there. The following year she began an extended tour of the Reich, taking Paul with her. They spent much of 1935 and 1936 living out of a suitcase.

When his mother returned to England to file copy and solicit more freelance commissions, Paul was left in the care of her fiancé's parents. He moved in with them permanently when he was six, so that he could go to school. The plan was for Norah to join them later, but she and her fiancé drifted apart. Paul, however, remained with his new family, an arrangement that suited all parties.

His mother's visits became less frequent, and when war was declared in 1939 they stopped. Her efforts to get Paul back to England failed. He was stranded in Germany for the duration, and his German family adopted him to spare him internment.

"The war gave me a perfect opportunity to demonstrate my loyalty to the nation and the family that had accepted me," he wrote later. "The most obvious way of helping the war effort was to join the Hitler Youth." Boys had to be at least 10 to enrol in its junior section, the Jungvolk, but Paul was so keen that he was allowed to join two months early, on Hitler's birthday.

When he swore the oath of allegiance to the Führer, he meant it. "I would have carved those words in my heart if they had asked me to," he wrote. In 1944 he joined the Feuerwehr, the auxiliary fire service, and was injured in an air-raid that destroyed his school. The following year he was an eyewitness to the surrender of Miltenberg by its Bürgermeister and the town's occupation by American troops.

In October 1945 a British Army officer appeared at the door of Briscoe's adoptive family and announced that he had half an hour to pack: he was going "home" – to a country whose language he had long forgotten and to a mother he had not heard from for four years. It was an unhappy reunion, followed by a shock. Norah Briscoe explained why she had not kept in touch: she had been in prison. She had been caught trying to pass information to the enemy. If one of the two charges against her had not been dropped, she would have been hanged.

She was, however, unrepentant, and proudly presented her Germanised son to her friends, including the soapbox anti-Semite "Jock" Houston, whose rabidity was so uncontrolled that he had been expelled from the British Union of Fascists. Later, Briscoe wrote that the last time he had heard talk like Jock's he had gone along with it, but hearing it again he could see how, even as a child, he should have recognised it for what it was.

Having repudiated the anti-Semitism with which he had been indoctrinated, Briscoe recounted his participation in Kristallnacht with shame. "What I did was a sin," he wrote, "a small part of one of the greatest sins of all time, which could never have happened without many lesser sins like mine. May God forgive me for it."

Paul Briscoe was a gifted raconteur, and delivered many talks about his experiences to audiences in Britain and Germany. He wrote two autobiographical memoirs, Foster Fatherland (2002) and My Friend the Enemy (2007). In each, he presented a child's-eye view of the hopes, fears and disappointments of an ordinary German family as the war progressed.

He described in detail the increasing privations of everyday life as the Reich began to crumble, including a visit to the dentist in which his tooth was stopped with melted-down coins. He recorded how Nazi propaganda poisoned every aspect of the school curriculum: his maths books taught subtraction by asking how much more profit was made by the Jew who charged more for his goods than the Aryan; his history lessons listed the evils of the British Empire. He was taught to think of the English as his enemy.

After the war Briscoe and his mother found a home and employment in the community of pacifists and misfits established by the literary critic John Middleton Murry at Lodge Farm, Thelnetham, Suffolk. In 1949 he found himself back in Germany on national service, in which he was ordered to dress in civvies and spy on meetings of Nazi sympathisers. After demobilisation he repaired historic buildings for the Ministry of Works.

In 1956 he married Monica Larter, an infant schoolteacher. In 1960 he, too, qualified as a teacher and he went on to teach woodwork and German at schools in Essex and Suffolk.

In 1975 he became joint manager of Monica's family farm at Framlingham, where he played an active part in the community as a church warden, conservationist and supporter of local charities.

He kept in close touch with his German foster family, and was reconciled to his mother, whose extremism faded, and who spent her last 30 years living with Paul, his wife and their children.

Paul Briscoe is survived by his wife, by their son and daughter, and by a daughter by an earlier relationship in Germany.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

References

(1) The Daily Telegraph (20th August, 2010)

(2) The Daily Mail (21st April, 2007)

(3) Norah Briscoe, Daemons and Magnets (unpublished)

(4) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 28

(5) Lord Rothermere, The Daily Mail (22nd January 1934)

(6) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 28

(7) The Daily Telegraph (20th August, 2010)

(8) Norah Briscoe, Daemons and Magnets (unpublished)

(9) The Daily Mail (21st April, 2007)

(10) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 44

(11) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 49

(12) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 51

(13) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 78

(14) The Daily Mail (21st April, 2007)

(15) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 82

(16) James Taylor and Warren Shaw, Dictionary of the Third Reich (1987) page 67

(17) Reinhard Heydrich, instructions for measures against Jews (10th November, 1938)

(18) Heinrich Mueller, order sent to all regional and local commanders of the state police (9th November 1938)

(19) Daniel Goldhagen, Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust (1996) page 100

(20) Erich Dressler, Nine Lives Under the Nazis (2011) page 66

(21) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 2

(22) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) pages 4-7

(23) The Daily Mail (21st April, 2007)

(24) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 70

(25) Dr Leigh Vaughan-Henry, letter to Emil Van Loo (6th June, 1939)

(26) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 71

(27) Archibald Ramsay, The Nameless War (1955) page 105

(28) Archibald Ramsay, House of Commons (22nd September, 1939)

(29) Richard Griffiths, Fellow Travellers of the Right (1983) page 370

(30) New York Times, (25th July, 1941)

(31) Anonymous letter sent to Scotland Yard (May, 1940)

(32) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 118

(33) The Daily Mail (21st April, 2007)

(34) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 119

(35) Guy Liddell, diary entry (13th March, 1941)

(36) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) pages 128-129

(37) Julie V. Gottlieb, Femine Fascism: Women in Britain's Fascist Movement (2003) page 287

(38) Guy Liddell, diary entry (17th June, 1941)

(39) German radio broadcast (2nd February, 1943)

(40) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 139

(41) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 140

(42) The Daily Mail (21st April, 2007)

(43) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 143

(44) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 151

(45) The Daily Telegraph (20th August, 2010)

(46) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 164

(47) The Daily Telegraph (20th August, 2010)

(48) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 169

(49) The Daily Mail (21st April, 2007)

(50) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 184

(51) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 204

(52) The Daily Telegraph (20th August, 2010)

(53) Norah Briscoe, Daemons and Magnets (unpublished)

(54) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 199

(55) The Daily Telegraph (20th August, 2010)

(56) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 204

(57) The Daily Telegraph (20th August, 2010)

(58) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 209

(59) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 210

(60) Paul Briscoe, My Friend the Enemy: An English Boy in Nazi Germany (2007) page 212

(61) The Daily Telegraph (20th August, 2010)