On this day on 13th August

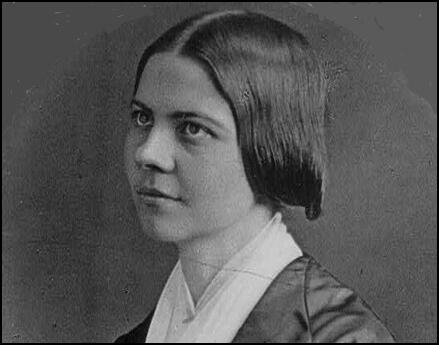

On this day in 1818 abolitionist and suffragist Lucy Stone was born in West Brookfield, Massachusetts. At the age of sixteen she became a teacher but after saving enough funds she studied at Oberlin College.

After graduating in 1847, Stone worked as a lecturer for the American Anti-Slavery Society. As well as speaking about the evils of slavery, Stone also advocated woman's suffrage and was responsible for recruiting Susan B. Anthony and Julia Ward Howe to the movement.

In 1855 Stone married Henry B. Blackwell, a man also active in the anti-slavery movement. During the marriage service they pledge that both partners would have absolutely equal rights in marriage. In protest against the laws that discriminated against women, Stone retained her own name.

In 1869 Stone, Julia Ward Howe and Josephine Ruffin formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) in Boston. Less militant that the National Woman Suffrage Association, the AWSA was only concerned with obtaining the vote and did not campaign on other issues.

Over the next twenty years Stone edited the Woman's Journal, a feminist weekly magazine, and wrote a large number of woman's suffrage leaflets.

Her daughter, Alice Stone Blackwell, edited the Woman's Journal for 35 years. Lucy's last words to her daughter were "make the world better".

Lucy Stone died in Dorchester, Massachusetts, on 18th October, 1893.

On this day in 1904 Fred Warren argues for socialism in Appeal to Reason.

With the introduction of private ownership in land came the period in the history of the human race when some man by reason of his superior strength or cunning, or some group of men, by reason of greater numbers, took possession of the land being used by another group and made slaves of the latter.

If men understood that the land is one of the great natural resources on which life depends, that it is the natural heritage of all men, and not a few, and it was so recognized through the long ages of savagery and barbarism, and that no title deed was recognized until civilization, so-called, made its appearance, I believe few would be willing to submit longer to the tyranny of the landlord and the master.

On this day in 1910 Florence Nightingale dies. Her biographer, Colin Matthew, has pointed out: "At the age of sixty Florence Nightingale considered herself old. Her friends and collaborators were dead, but her health improved. The thin, waspish woman who sent mordant, aphoristic letters to ministers now metamorphosed into a stout, benevolent old lady. She tried to keep up with public-health matters but she was increasingly out of touch.... She continued to write sentimental addresses to probationers until 1889, but by now her eyesight was failing.... She spent almost the whole of her final fifteen years in her room in South Street."

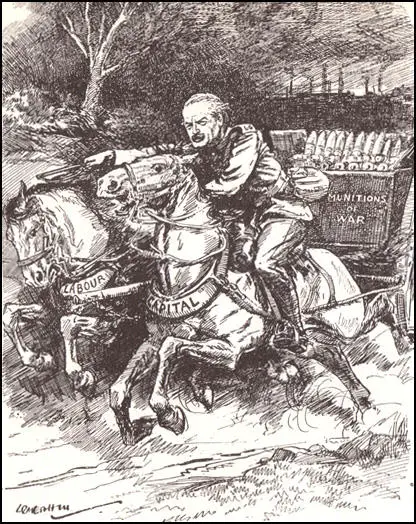

On this day in 1917 George Riddell describes David Lloyd George as a great war leader. "He (David Lloyd George) is a remarkable combination of forces; an orator and a man of action. His energy, capacity for work, and power of recuperation are remarkable. He has an extraordinary memory, imagination, and the art of getting at the root of a matter... He is not afraid of responsibility, and has no respect for tradition or convention. He is always ready to examine, scrap, or revise established theories and practices".

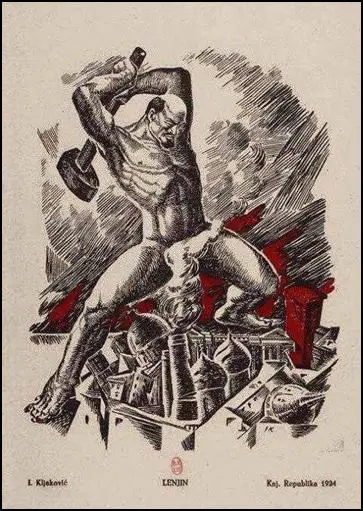

On this day in 1921 Walter Duranty, writes in the New York Times about War Communism: "Lenin has thrown communism overboard. His signature appears in the official press of Moscow in August 9, abandoning State ownership, with the exception of a definite number of great industries of national importance - such as were controlled by the State in France, England and Germany during the war - and re-establishing payment by individuals for railroads, postal and other public services.

On this day in 1946 H. G. Wells dies. Wells was appalled by the outbreak of the Second World War and wrote extensively about the need to make sure that we used the conflict to establish a new, rational world order. At the time of his death he was working on a project that dealt with the dangers of nuclear war. Margaret Cole later wrote: "I was just one of the many young who over three generations at least took their hope of the world from the vivid, many-gifted, generous, cantankerous personality, and accepted, not merely once but again and again over forty years, his eager conviction that the ideal of Socialism, which included world government, the abolition of all authority not based on reason, and of all inequality based on prejudice or privilege of any kind, of complete freedom of association, speech and movement, and of an immense increase of human welfare and material resources achieved by all-wise non-profit-making organisation of economic life, both could and would save humanity within a measurable space of time. Only at the very end, when he was all but on his death-bed, did H. G. Wells give up hoping for humanity."

Herbert George Wells, the son of an unsuccessful tradesman, was born in Bromley on 21st September, 1866. After a basic education at a local school, Wells was apprenticed as a draper. Wells disliked the work and in 1883 became a pupil-teacher at Midhurst Grammar School.

While at Midhurst Wells won a scholarship to the School of Science where he was taught biology by T. H. Huxley. Wells found Huxley an inspiring teacher and as a result developed a strong interest in evolution. Wells founded and edited the Science Schools Journal while at university. Wells was disappointing with the teaching he received in the second year and so in 1887 he left without obtaining a degree.

Wells spent the next few years teaching and writing and in 1891 his major essay on science, The Rediscovery of the Unique , was published in The Fortnightly Review. In 1895 Wells established himself as a novelist in 1895 with his science fiction story, The Time Machine. This was followed by two more successful novels, The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896) and The War of the Worlds (1898).

Wells also became very popular in the United States. The popular magazine Cosmopolitan serialised two of his books, The War of the Worlds (1897) and First Man in the Moon (1900). His work also appeared in Collier's Magazine, the New Republic and the Saturday Evening Post.

Wells also began writing non-fiction books about politics, technology and the future. This included Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress Upon Human Life and Thought (1901), The Discovery of the Future (1902) and Mankind in the Making (1903). These books impressed the three leaders of the Fabian Society, George Bernard Shaw, Sidney Webb and Beatrice Webb. Wells accepted their suggestion that he should join the society.

Once a member of the Fabian Society, Wells tried to change it. Rather than a small group of intellectuals discussing socialist reform, Wells thought that it should be a large pressure group agitating for change. When the existing leadership resisted these ideas, Wells attempted to gain control of the organisation. Wells managed to gain election to the Fabian Society's Executive Committee but gained little support for change from the rest of the group.

In 1904 Beatrice Webb wrote: "We had a couple of days with H. G. Wells and his wife at Sandgate, and they are returning the visit here. We like him very much - he is absolutely genuine and full of inventiveness, a speculator in ideas, somewhat of a gambler but perfectly aware that his hypotheses are not verified. In one sense he is a romancer spoilt by romancing, but in the present stage of sociology he is useful to gradgrinds like ourselves in supplying us with loose generalizations which we can use as instruments of research."

Wells resigned from the Fabian Society in 1908 but continued to be active in the campaign for socialism. His book A Modern Utopia expressed a desire for a society that was run and organised by humanistic and well-educated people. Wells, who was extremely critical of the role that privilege and hereditary factors in capitalist society and in his utopia, people gain power as a result of their intelligence and training. Wells argued: "The Socialist (asks) what freedom is there today for the vast majority of mankind? They are free to do nothing but work for a bare subsistence all their lives, they may not go freely about the earth even, but are prosecuted for trespassing upon the health-giving breast of our universal mother. Consider the clerks and girls who hurry to their work of a morning across Brooklyn Bridge in New York, or Hungerford Bridge in London; go and see them, study their faces. They are free, with a freedom Socialism would destroy. Consider the poor painted girls who pursue bread with nameless indignities through our streets at night. They are free by the current standard. And the poor half-starved wretches struggling with the impossible stint of oakum in a casual ward, they too are free! The nimble footman is free, the crushed porter between the trucks is free, the woman in the mill, the child in the mine. Ask them! They will tell you how free they are."

In his early scientific writings Wells predicted the invention of modern weapons such as the tank and the atom bomb. He was therefore horrified by the outbreak of the First World War. Unlike many socialists, he supported Britain's involvement in the war, however, he believed politicians should use this opportunity to create a new world order.

Wells was encouraged by the news of the communist revolution in Russia. He visited the country and lectured Lenin and Trotsky on how they should run their country. Wells was disillusioned by what he saw in Russia and in 1920 Wells published The Outline of History. The book described human history since the earliest times and attempted to show how society had evolved to the present state. Wells illustrated the triumphs and failures and pointed out the dangers that faced the human race. The main theme of the book was that the world would be saved by education and not by revolution.

Wells book was widely discussed and the abridged version, A Short History of the World, published in 1922, sold in large numbers. In the 1922 General Election Wells was the Labour Party candidate for London University. One of those who helped him in his campaign was Ella Winter. She later recalled in her autobiography, And Not to Yield (1963): "The constituency consisted of London University teachers and students anywhere in the world, present and past; the campaign was carried out mainly by mail. I had known Wells slightly, but never before seen him troubled about the effects of his well-known unconventional behavior. Had we not regarded him as the apostle of women's rebellion and women's freedom? I was disillusioned when he wondered whether he ought to send out a letter justifying, possibly excusing, those actions. I was also surprised to find how little he knew of, and how childish he seemed about, practical politics." The campaign was unsuccessful and Wells only won 19% of the vote.

Wells was now considered to be one of the world's most important political thinkers and during the 1920s and 30s he was in great demand as a contributor to newspapers and journals. In his books and articles H. G. Wells argued that society had reached the stage where it needed world government and strongly supported the League of Nations that was established after the First World War. Wells also stressed that society needed to establish structures that ensured that the most intelligent gained power. Some socialists criticised Wells claiming that he was now preaching a form of elitism.

David Low became one of his friends: "H. G. Wells had the rare ability to make himself clear, to make difficult ideas assimilable, to excite curiosity and to prompt enquiry. Scientist, novelist, sociologist, prophet - but primarily the co-ordinating link between all these and the ordinary man, who, without his like, must live forever in darkness of mind. He was most effective in print, and more effective among a private company of half a dozen or so than at a public meeting. That was his trouble, because frequently he liked a public meeting, and he just hadn't the equipment. The vibrant baritone of his writing came out a peevish soprano in his speech. The handicap of a high-pitched voice that squeaked when he got wound up was easily imitated and ridiculed." Clement Attlee was another one who remarked on his speaking voice: "H. G. Wells was on the platform, speaking with a little piping voice; he was very unimpressive."

Some socialists became critical of his attitude towards the Great Depression: The left-wing MP Jennie Lee wrote about a meeting with Wells in 1929: "H. G. Wells was one of the bright guiding stars of my youth. I read avidly everything he wrote. That day in Parliament there had been a violent debate about all the issues that meant most to me - the cruelty and indignities of the Means Test, failure to get on with the building of urgently needed houses, schools and hospitals, and all this against a background of hundreds of thousands of unemployed building workers. I arrived at Great College Street brimming over with indignation. H. G. Wells brushed aside anything I tried to say, returning obsessively to the teaching of history in schools. We began glaring at one another with growing hostility. So this was H. G. Wells, this dumpy little man with the squeaky voice, totally indifferent to the problems that concerned the great mass of ordinary people."

In his novel The Shape of Things to Come published in 1933, Wells describes a world that had been devastated by decades of war and was now being rebuilt by the use of humanistic technology. David Low pointed out: "H. G. Wells had the rare ability to make himself clear, to make difficult ideas assimilable, to excite curiosity and to prompt enquiry. Scientist, novelist, sociologist, prophet - but primarily the co-ordinating link between all these and the ordinary man, who, without his like, must live forever in darkness of mind."

In 1934 H. G. Wells visited the Soviet Union and the United States. Although Wells clearly preferred what President Franklin D. Roosevelt was trying to do, some people believed he was far too sympathetic to Joseph Stalin. One of his main critics was his old adversary at the Fabian Society, the successful writer, George Bernard Shaw.