Stephen Tomlin

Tomlin was an artist and he became involved with the Bloomsbury Group,. This group of left-wing intellectuals included, Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, Lytton Strachey, E. M. Forster, Duncan Grant, Gerald Brenan, Ralph Partridge, Bertram Russell, Ottoline Morrell, Leonard Woolf, David Garnett, Roger Fry, Desmond MacCarthy and Arthur Waley.

Frances Marshall described Tomlin: "The two sides of his personality were fused together as it were by an excellent brain inherited from his father the judge (Lord Tomlin), shown in his enjoyment of arguments with a distinctly legal flavour.... Tommy (Tomlin) was on the short side, squarely built, with a large head set on a short neck. He had the striking profile of a Roman emperor on a coin, fair straight hair brushed back from a fine forehead, a pale face and grey eyes."

Tomlin became a regular visitor to Ham Spray House, the home of Lytton Strachey, Dora Carrington and Ralph Partridge. According to Strachey's biographer, Stanford Patrick Rosenbaum, they created: "A polygonal ménage that survived the various affairs of both without destroying the deep love that lasted the rest of their lives. Strachey's relation to Carrington was partly paternal; he gave her a literary education while she painted and managed the household. Ralph Partridge... became indispensable to both Strachey, who fell in love with him, and Carrington." However, Frances Marshall denied that the two men were lovers and that Lytton quickly realised that Ralph was "completely heterosexual".

Michael Holroyd, the author of Lytton Strachey (1994), has argued: "Tomlin, being bisexual, for a brief spell occupied a virtuoso position in the Ham Spray régime... The mercurial Stephen Tomlin who, greatly attracting Lytton and repelling Ralph, spiralled round the Ham Spray molecule causing shock waves everywhere." " Tomlin began an affair with Henrietta Bingham, Carrington's lover. In July 1924 he took Bingham to Scotland. Carrington wrote to Gerald Brenan complaining that "Henrietta repays my affections almost as negatively as you find I do yours."

Tomlin began an affair with Carrington in 1926. Carrington's husband Ralph Partridge, strongly objected to the relationship, "fearing he (Tomlin) was someone more likely to destroy than to create happiness." Frances Marshall agreed: "One side of his character was creatively gifted, charming and sensitive; the other was dominated by a destructive impulse (fuelled probably by deep neurotic despair) whose effect was that he couldn't see two people happy together without being impelled to intervene and take one away, leaving the other bereft. Or it would take the form of a direct bid for power over others - whether male or female, for he was bi-sexual - which he was well-equipped to exert. The sequel would be a fit of suicidal depression and guilt-feelings."

Tomlin was also having an affair with Carrington's friend, Julia Strachey. His affair with Carrington came to an end when Tomlin married Julia in July 1927. The married couple rented a stone cottage at Swallowcliffe in Wiltshire. Carrington was a regular visitor: "Really its equal to Ham Spray in elegance and comfort, only cleaner and tidier."

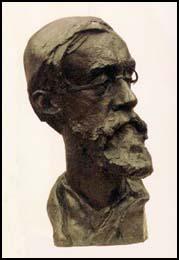

In July 1931 Tomlin began working on a bust of Virginia Woolf. Her biographer, Hermione Lee, argued that being sculpted by Tomlin "made her think of herself as an image, a thing: she hated it, even more than sitting for her portrait." Quentin Bell added: "For somehow Virginia managed to forget, in agreeing to the proposal, that the sculptor must inevitably wish to look at his sitter and Virginia should have recollected that one of the things she most disliked in life was being peered at. A very few friends had been allowed to make pictures; some were made by stealth." Despite this, Bell believes that it was a successful work of art: "It is not flattering. It makes Virginia look older and fiercer than she was, but it has a force, a life, a truth, which his other works (those I have seen) do not possess."

Tomlin also produced a bust of Lytton Strachey. Later that year he became extremely ill. He had a fever that would not go away and constantly felt tired. At first he was diagnosed as having typhoid. He then saw another specialist who suggested it was ulcerative colitis. Frances Marshall pointed out: "In those days bulletins were published in the daily papers mentioning the progress of well-known people's illnesses. Lytton rated this degree of importance and the press often rang up, though the nice lady at the local exchange dealt with their queries and kept them supplied with news... On Christmas Day 1931 he was given up for dead. In the evening he made an astonishing recovery from near-unconsciousness."

On 19th January 1932, Dora Carrington asked the nurse who was caring for him if there was any chance that he might survive the illness. She replied: "Oh no - I don't think so now". Soon afterwards she went into the garage and tried to kill herself. However, during the night Ralph Partridge went looking for her and "found her in the garage with the car engine running, rushed in and dragged her out".

Lytton Strachey died of undiagnosed stomach cancer on 21st January 1932. His death made Carrington suicidal. She wrote a passage from David Hume in her diary: "A man who retires from life does no harm to society. He only ceases to do good. I am not obliged to do a small good to society at the expense of a great harm to myself. Why then should I prolong a miserable existence... I believe that no man ever threw away life, while it was worth keeping."

According to Michael Holroyd, the author of Lytton Strachey (1994): "Of all the friends he (Ralph Patridge) invited to Ham Spray it was Stephen Tomlin who appeared most successful in halting her from making another attempt at suicide." Dora Carrington wrote in her journal: "He (Tomlin) persuaded me that after a serious operation or fever, a man's mind would not be in a good state to decide on such an important step. I agreed - so I will defer my decision for a month or two until the result of the operation is less acute." After he returned home, Carrington wrote to him: "You made this last week bearable which nobody else could have done. Those endless conversations were not quite pointless."

Frances Marshall was with Ralph Partridge when he received a phone-call on 11th March 1932. "The telephone rang, waking us. It was Tom Francis, the gardener who came daily from Ham; he was suffering terribly from shock, but had the presence of mind to tell us exactly what had happened: Carrington had shot herself but was still alive. Ralph rang up the Hungerford doctor asking him to go out to Ham Spray immediately; then, stopping only to collect a trained nurse, and taking Bunny with us for support, we drove at breakneck speed down the Great West Road.... We found her propped on rugs on her bedroom floor; the doctor had not dared to move her, but she had touched him greatly by asking him to fortify himself with a glass of sherry. Very characteristically, she first told Ralph she longed to die, and then (seeing his agony of mind) that she would do her best to get well. She died that same afternoon."

Stephen Tomlin, who separated from Julia Strachey in 1934, died on 10th January 1937.

Primary Sources

(1) Francis Partridge, Memories (1981)

Returning we saw Lytton and Carrington on the lawn. Tea was ready. ... Now it was over and Tommy (Stephen Tomlin) was standing with his back to the fireplace talking to Julia and me. He couldn't fail to be aware that Lytton was putting on his outdoor shoes, in obvious hope of a walk with him. This he does in a way all his own. He puts each shoe down with great care just in front of the foot to which it belongs, and then slips it gently in, obviously enjoying the process. Tommy was manifesting his inveterate passion for being in demand by more than one person at once, and I remembered that Ralph told me how Lytton had confessed to having put a love letter under what he believed to be Tommy's door. But not till Julia had left the room did Lytton say in a peculiarly mild voice, "Do you feel like a little walk?" They set off, and as Ralph and Carrington were driving Alix home, Julia and I were left alone together, discussing whether she would look for a job or not. She was nowhere nearer a decision.

"Swallowcliffe is definitely impossible unless Tommy and I are married - but I shouldn't be surprised if we do get married." "No. Nor should I," I said somewhat untruthfully. I don't believe she is really in love with Tommy, but it might rescue her from what she fears may be an unhappy future, and so make her happier. If only Tommy weren't so neurotic and alarmingly destructive, but of course he's extremely intelligent, and this weekend he has been sane and charming.

(2) Quentin Bell, Virginia Woolf: A Biography (1972)

Stephen Tomlin, a charmer whose charm totally failed to work upon Virginia, had nevertheless persuaded her to sit to him for a sculptured head. Posterity may be glad that he did so. No-one else had any cause to be glad. For somehow Virginia managed to forget, in agreeing to the proposal, that the sculptor must inevitably wish to look at his sitter and Virginia should have recollected that one of the things she most disliked in life was being peered at. A very few friends had been allowed to make pictures; some were made by stealth. She didn't like being photographed, but if a painter or a photographer is unwelcome, how much more so a modeller? The man with the camera may be offensive but his offence is swiftly committed. The painter is worse in this respect, but he may, like Lily Briscoe, be supposed to regard you as no more than a part of the composition - an interesting but perhaps not an essential accent. But a sculptor has but one object: yourself - you from in front, you from behind, you from every conceivable angle - and his is a staring, measuring, twisting and turning business, an exhaustive and a remorseless enquiry. Virginia couldn't stand it. His face staring into hers appeared ugly, obscene and impertinent. It seemed an insult to her personality, pinning her down, wasting her precious time - insufferable.

In vain Vanessa tried to ease matters by coming with her and making a sketch of her own. Ethel came too. Nothing answered. Tomlin was intolerable. He insisted on making plans to suit his own convenience. Then he was not punctual and she, Virginia, had to plod along dusty streets - a proceeding which if the object had been different she would have found delightful - to reach his studio, and in short she was, as Vanessa said, in "a state of rage and despair," so that after four short sittings-how short time seems to those who paint and how long to those who sit-she struck. Two further sessions were by some prodigy of persuasion vouchsafed, and then she would have no more of it. She was free of the affliction. Poor Tomlin was miserable. The work had to be left unfinished without any hope that it would ever be brought to a satisfactory conclusion.

Now the final irony is this: Stephen Tomlin's best claim to immortality rests upon that bust. It is not flattering. It makes Virginia look older and fiercer than she was, but it has a force, a life, a truth, which his other works (those I have seen) do not possess. Virginia gave him no time to spoil his first brilliant conception. Irritated, despondent, reckless, he pushed his clay into position and was forced to give, while there was still time, the essential structure of her face. Her blank eyes stare as though in blind affronted dismay, but it is far more like than any of the photographs. So far as Virginia herself was concerned, by August 1931 the business was over.

(3) Francis Partridge, Memories (1981)

If such a condition exists, as I believe it does, Stephen Tomlin (Tommy) was a case of dual personality. One side of his character was creatively gifted, charming and sensitive; the other was dominated by a destructive impulse (fuelled probably by deep neurotic despair) whose effect was that he couldn't see two people happy together without being impelled to intervene and take one away, leaving the other bereft. Or it would take the form of a direct bid for power over others - whether male or female, for he was bi-sexual - which he was well-equipped to exert. The sequel would be a fit of suicidal depression and guilt-feelings. The two sides of his personality were fused together as it were by an excellent brain inherited from his father the judge (Lord Tomlin), shown in his enjoyment of arguments with a distinctly legal flavour. He broke several hearts, but certainly gave more happiness than the reverse and had many loyal friends; if one could forget his darker side he was an interesting and even enchanting companion. Personally I did forget it most of the time, although on the rare occasions he switched on his charm for my benefit I found it unconvincing; but to Ralph the destructive element was anathema, and when Tommy revealed it he reacted with irritation - even dislike.

Tommy was on the short side, squarely built, with a large head set on a short neck. He had the striking profile of a Roman emperor on a coin, fair straight hair brushed back from a fine forehead, a pale face and grey eyes.

(4) Michael Holroyd, Lytton Strachey (1994)

It had been decided, in the event of a crisis occurring, to send for another of Carrington's lovers, Stephen Tomlin. This was Ralph's idea; he wanted to mobilize anyone who might help to ensure her safety. They had got in touch with him and he was standing by. While Tommy was in the house, it was felt, Carrington would not attempt to take her own life. It was a cruel but clever expedient, for its success depended upon Tommy being so unbalanced and neurotic, so prone himself to suicide, shattered by his brother Garrow having been killed flying only the previous month, by the failure of his marriage to Julia Strachey and by all the supports in his life tottering, that Carrington's sense of responsibility would be aroused, and she would pull herself together to attend to him. Tommy's principal relations with other people contained a strong element of dependence. Lytton was not merely one of his closest friends; he relied, in some almost filial way, upon his existence. In the event of Lytton's death, Carrington would have to control herself and Tommy.