Deep Underground Shelters

Several reports had been commissioned before the war about the possible impact of targeted air-raids on British civilians. It was calculated that 3,500 tons of bombs would be dropped in the first twenty-four hours. By the time the all-clear sounded, 58,000 Londoners would have been killed. Each ton of bombs would cause fifty casualties, a third of which would be fatal. (6) According to another report, the first week of serious air raids on the capital would leave some 66,000 Londoners dead and another 134,000 seriously injured. (1)

Many, including the Committee of Imperial Defence, anticipated that the maintenance of public order would pose the greatest problem. It was suggested that the first raids would generate mass panic and Londoners would emerge from their shelters and take part in widespread and destructive rioting. The government therefore decided that a large part of the Territorial Army should not be sent abroad but held in reserve to preserve law and order at home. (2)

Reputable scientists offered alarming statistics. John Haldane, warned that the sound wave from a bomb would "literally flatten out everything in front" of it. Those within range not immediately killed would be permanently disabled, their eardrums would burst inward and people would be "deafened for life". The Mental Health Emergency Committee agreed, reporting in 1939 that psychiatric casualties were likely to exceed physical injuries by three to one, while three or four million people would succumb to hysteria. (3) Haldane advised the government that they should build a network of deep tunnels under London to give real protection but this advice was rejected. (4)

Wealthy people living in London could enjoy deep shelters. The most expensive London hotels and restaurants provided secure underground accommodation for their customers. Some restaurants provided camp beds in their cellars. The Dorchester Hotel, which was considered to be secure because of its reinforced-concrete structure, turned its basement gymnasium into an air-raid dormitory. Lady Diana Cooper felt "quite secure" spending time "with all that was most distinguished in London society, including members of the government such as Lord Halifax. (5)

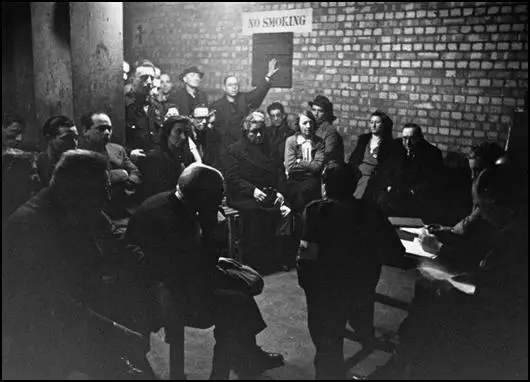

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was very active in London. Phil Piratin, a Communist councillor in Stepney, became an ARP warden. He was also active in converting pre-war East End tenants' associations into Shelter Committees to keep up the battle for deep shelters and to press for better facilities in public surface shelters. As the government did not respond quickly enough members of the CPGB decided to take direct action against The Savoy Hotel had turned its underground banqueting hall as a shelter for its customers. (6)

As the government did not respond quickly enough members of the CPGB decided to take direct action. Piratin decided to lead a party of seventy of the borough's residents to the Savoy to demand access to its shelter. "We decided what was good enough for the Savoy Hotel parasites was reasonably good enough for Stepney workers and their families. We had an idea that the hotel management would not see eye to eye with this so we organised an invasion without their consent." (7)

On 15th September, 1940, about a hundred East Enders, rushed on the hotel after the air-raid sirens sounded and occupied the shelter. However, the protesters were soon removed. (8) The government became worried about public order and one of its junior ministers wrote in his diary: "Everyone is worried about the feeling in the East End... There is much bitterness. It is said that even the King and Queen were booed the other day when they visited the destroyed." (9)

Communist shop-stewards threatened to go on strike if their employers did not provide deep shelters. The CPGB newspaper, The Daily Worker, claimed: "The shelter policy of the government is not just a history of incompetence and neglect, it is a calculated class policy... A determination not to provide protection because profit is placed before human lives... the bankruptcy of the government's shelter policy is plain for all to see... safe in their own luxury shelters the ruling class must be forced to give way." (10)

The News Chronicle, Daily Mail and Evening Standard. also became involved in the campaign to force the government to build more public shelters. The authorities remained opposed and ARP lecturers were instructed to point out the dangers. "What happens if the doors get blocked? asked a warden in the Mile End Road. "Then people won't be able to get up from the bowels of the earth and will just have to remain there with RIP written on top." (11)

Primary Sources

(1) Barbara Castle, Fighting All The Way (1993)

What we also lacked was an adequate shelter policy, and I had been agitating together with our left-wing group on the Council for the deep shelters which Professor J. B. S. Haldane had been advocating. Haldane, a communist sympathizer and eminent scientist, had studied at first hand the effects of air raids on the civilian population during the Spanish Civil War and had reached conclusions on the best way to protect them, which he had embodied in a book ARP published in 1938. In it he argued that high explosive, not gas, would be the main threat. He pointed out that modern high explosives often had a delayed-action fuse and might penetrate several floors of a building before bursting and that therefore basements could be the worst place to shelter in. He stressed the deep psychological need of humans caught in bombardment to go underground and urged the building of a network of deep tunnels under London to meet this need and give real protection.

The government did not want to know. In 1939 Sir John Anderson, dismissing deep shelters as impractical, insisted that blast - and splinter-proof protection was all that was needed and promised a vast extension of the steel shelters which took his name. These consisted of enlarged holes in the ground covered by a vault of thin steel. They had, of course, no lighting, no heating and no lavatories. People had to survive a winter night's bombardment in them as best they could. In fact, when the Blitz came, the people of London created their own deep shelters: the London Underground. Night after night, just before the sirens sounded, thousands trooped down in orderly fashion into the nearest Underground station, taking their bedding with them, flasks of hot tea, snacks, radios, packs of cards and magazines. People soon got their regular places and set up little troglodyte communities where they could relax. I joined them one night to see what it was like. It was not a way of life I wanted for myself but I could see what an important safety-valve it was. Without it, London life could not have carried on in the way it did.

(2) Kingsley Martin was the editor of the New Statesman during the Second World War. He wrote about his experiences in his autobiography, Editor, in 1968.

In the West End, we could "take" the raids we got; whether we could have survived many more like the last two raids in the spring of 1941, when many of London's gas and water mains were destroyed, I don't know. We might not have been able to carry on, but bombs do not induce surrender. The Government had miscalculated the effect of raids; the 300,000 papiermache coffins which were ready when the bombing began were never used and the hospitals, which were cleared for patients who were expected to be driven mad by raids, remained empty. On the contrary, bombs tended to cure psychological maladies. Many people who were neurotic about the prospect of war were cured by its reality. They had too much to do to have time to be frightened.

In the late summer of 1940 German bombers for the first time began their raids on Dockland. I was one of a small company who went down to the East End in early mornings with Bob Boothby, then Under-Secretary to the Ministry of Food. We took with us a mobile canteen which provided hot drinks for people who had been bombed out. I got to know Father Groser, the happiest example of a priestly saint, who was then and afterwards beloved by co-workers of all denominations as well as by the poor he helped. I recall one morning my pleasure in being able to ring him up to say that I had just received a cheque for £1,000 to help his work in the Blitz.

Ritchie Calder wrote of the effects of the Blitz in the East End in a vivid series of articles which I published in the New Statesman. The number of dead was small, but the army of refugees was larger than expected and he pointed out that, if you were homeless and had lost everything you possessed, you were, in effect, a casualty. No provision had been made for these destitute people, and Ritchie caused a sensation when he described how many of them were herded into schools which were themselves afterwards bombed. I myself wrote an article about a vast, underground food store in Stepney where hundreds of poor people took shelter among the crates of margarine, and where stacks of boxes containing London's food supply were being used as screens for unofficial lavatories. I made a frontal attack on the Home Secretary, Sir John Anderson, and the local authorities for their total failure to deal with an increasingly shocking and dangerously unhygienic situation.

(3) Joan Miller, One Girl's War (1970)

We who lived in London through the Blitz were constantly observing pathetic and heroic sights, and constantly experiencing some fresh excess of outrage; even the violently altered appearance of the city was a shock to the system. It was disorientating to find a well-known area transformed into a nightmare territory of shattered buildings, horrifying craters and acres of rubble. Places to which you had attached importance were suddenly no longer there. Eight Wren churches were destroyed in a single night. Everyone had stories of their own lucky escapes or those of friends. Many, of course, weren't lucky at all. Shelterers in the Underground were among the earliest casualties: Trafalgar Square, Bounds Green, Praed Street and Balham Stations all suffered direct hits before the end of 1940. A night-club in Leicester Square, the Cafe de Paris, a haunt of mine, was bombed in the spring of 1941 and turned, in seconds, from a place of gaiety to a shambles. Like Hatchetts restaurant, it was believed to be safe because it was underground.

Through it all, of course, things kept going. A milkman picking his steps across a newly ruined road, a postman collecting mail from a letter box mysteriously left intact in the middle of a wasteland - these, among other potent images, symbolized the Londoners' particular refusal to be intimidated. I know of no one who lost heart, gave way to nerves, or experienced despair. Those who suffered most, it seemed at times, gained from somewhere the hardihood to endure it. My ex-colleague John Dickson Carr, whose house was twice demolished around him, was able to joke about these experiences.