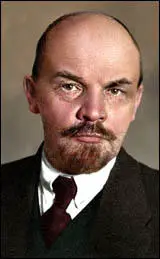

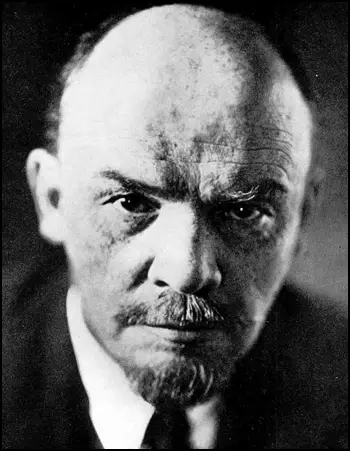

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Illich Ulyanov (later known as Lenin) was born in Simbirsk, Russia, on 10th April, 1870. His father, Ilya Ulyanov, a former science teacher, had recently become a local schools inspector. He held conservative views and was a devout member of the Russian Orthodox Church. Lenin had two older siblings, Anna (born 1864) and Alexander (born 1868). They were followed by three more children, Olga (born 1871), Dmitry (born 1874), and Maria (born 1878).

His mother, Maria Blank Ulyanov, had a German grandmother, and according to Maria Ulyanov. the children were "reared to a certain degree in German traditions". Maria was largely self-educated and taught herself German, French and English. She helped Vladimir with his studies and taught him to read and gave him piano lessons. He later gave this up as he thought playing the piano was "an unbecoming occupation for boys". (1)

In 1874 Ilya Ulyanov was promoted to the post of director of schools. "Upon his shoulders lay the responsibility for the training, assignment, and discipline of the teachers, and for the organization and curricula of the elementary schools. In a province as backward and poor as Simbirsk the job was likely to be of back-breaking proportions. It took not only career considerations but real devotion to education on the part of Ulyanov to exchange the more congenial post of the high school teacher... for the task of supervising elementary education in a bleak province of about one million inhabitants." (2)

Lenin was educated at the Simbirsk Gymnasium. His headmaster was Fyodor Kerensky, the father of Alexander Kerensky. Although Lenin despised the conservative views of his teachers he still managed to do well in his examinations. While at school he developed a love for history and languages. His brother, Dmitry, later recalled the meticulous care that he put into his homework: "He never wrote them on the eve of the day when they were to be handed in, as most students did. On the contrary, on being assigned the subject, Vladimir Ilyich set to work immediately. On a quarter of a sheet of paper he would make an outline together with the introduction and conclusion. He would then take another sheet, fold it in half, and make a rough draft on the left side of the paper, in accordance with his outline. The right side or margin remained clear. Here he would enter additions, explanations, corrections, as well as source indications... Then, shortly before it was necessary to hand it in, he would take some new clean sheets of paper and write the composition... referring to his notes and sources in various books." (3)

His father was a monarchist and was a supporter of Tsar Alexander II and his Emancipation Manifesto that proposed 17 legislative acts that would free the serfs in Russia. Alexander announced that personal serfdom would be abolished and all peasants would be able to buy land from their landlords. The State would advance the the money to the landlords and they would recover it from the peasants in 49 annual sums known as redemption payments. (4) However, as his critics pointed out: "With a population of sixty-seven million, Russia had twenty-three million serfs belonging to 103,000 landlords. The arable land which the freed peasantry had to rent or buy was valued at about double its real value (342 million roubles instead of 180 million); yesterday's serfs discovered that, in becoming free, they were now hopelessly in debt." (5)

It is claimed that Ilya Ulyanov "believed in change, redemption, improvement, enlightenment, good deeds, cold baths, fresh air, and self-discipline" When the Tsar was assassinated in April 1881, he was extremely upset and left his office immediately, came home, put on his uniform and went to the cathedral, where a memorial service was conducted. "His children remarked on how shaken he was by the tragic event." (6)

Ilya Ulyanov died of a brain haemorrhage in January 1886, when Lenin was 16. Soon afterwards he lost his faith. A friend later wrote: "When he perceived clearly that there was no God, he tore the cross violently from his neck, spat upon it contemptuously, and threw it away. In short he freed himself from religious prejudices in typical revolutionary Leninist fashion, without prolonged hesitation or timid consideration, without mental struggle with the spirit of doubt." (7)

Lenin's brother, Alexander Ulyanov studied natural sciences at St. Petersburg University. He was an excellent student and at first he took no interest in politics and told a fellow student in 1886: "It is absurd, even immoral, for a man who has no understanding of medicine to cure the sick. How much more absurd and immoral it is to seek to heal social ills without understanding their cause." (8)

Lenin idolized his older brother but was dismissive of his lack of interest in politics: "Alexander will never be a revolutionist. On his last summer visit home he spent his time preparing a dissertation on Annelides and worked constantly with his microscope. A revolutionist cannot possibly devote so much time to the study of Annelides." Ulyanov's studies won him a gold medal in zoology. However, after the death of his father, he became involved in politics. (9)

Execution of Alexander Ulyanov

Alexander Ulyanov became a member of the People's Will (Narodnaya Volya) and organization that had assassinated Alexander II and now had plans to kill his son, Alexander III. In secret meetings at his apartment, plans were laid to kill the Tsar on 1st March 1887, the sixth anniversary of the assassination of his father. Ulyanov also prepared a manifesto to the Russian people, to be published immediately after the Tsar's death. It began: "The spirit of the Russian land lives and the truth is not extinguished in the hearts of her sons." (10)

As David Shub, the author of Lenin (1948), has pointed out, the secret police was aware of the conspiracy. "The date was advanced several days when the terrorists learned that the Tsar was planning to leave for his summer palace in the Crimea. Assassins were planted in the square before St Isaac's Cathedral. But the Tsar did not appear and at twilight the conspirators returned to their underground headquarters. Ulyanov then heard that on 28 February the Tsar was to drive along the Nevsky Prospect, probably to attend memorial services at his father's crypt in the Cathedral of St Peter and St Paul. Once more the terrorists waited, but no Tsar's carriage appeared. The secret police, suspecting an assassination plot, had warned the monarch to remain in the Winter Palace. Hours later the terrorists left their stations along the Nevsky and met in a tavern. One of them, Andreiushkin, had been shadowed for days by detectives. They followed him to the tavern, where he and his comrades were seized." (11)

In Ulyanov's possession they found a code-book with a number of incriminating names and addresses, including that of the Polish revolutionary leader, Josef Pilsudski. Over the next few days hundreds of suspects were picked up in various cities and towns throughout Russia, the police having obtained the key to the code by torturing one of the terrorists. They singled out fifteen men, including Ulyanov, for trial. The charge: conspiracy to assassinate the Tsar. (12)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. Please visit our support page. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Alexander's mother, Maria Ulyanov, wrote a letter to Tsar Alexander III and asked for permission to see her son. The Tsar wrote in the margin of the letter: "I think it would be advisable to allow her to visit her son, so that she might see for herself the kind of person this precious son of hers is." During her visit Ulyanov told his mother that he was sorry for the suffering he had caused her but admitted that his first allegiance was to the revolutionary movement. As a revolutionist, he had no alternative but to fight for his country's liberation. (13)

At his trial Alexander Ulyanov refused to be represented by counsel and carried out his own defence. In an attempt to save his own comrades, he confessed to acts he had never committed. In his final address to the court Ulyanov argued: "My purpose was to aid in the liberation of the unhappy Russian people. Under a system which permits no freedom of expression and crushes every attempt to work for their welfare and enlightenment by legal means, the only instrument that remains is terror. We cannot fight this regime in open battle, because it is too firmly entrenched and commands enormous powers of repression. Therefore, any individual sensitive to injustice must resort to terror. Terror is our answer to the violence of the state. It is the only way to force a despotic regime to grant political freedom to the people." He stated that he was not afraid to die as "there is no death more honourable than death for the common good". (14)

Ulyanov's mother pleaded with her son to ask for imperial clemency. He refused, although some of his co-defendants petitioned the Tsar and their death sentences were commuted. Helen Rappaport, the author of Conspirator: Lenin in Exile (2009): "On 8 May, having been lulled into a false sense of security that their sentences were to be commuted, the men were woken at 3.30 a.m. and informed that they were to be executed in half an hour's time. The prison officials had been so secretive in the construction of the gallows during those intervening three days that none of the prisoners in the isolation block had known. But they only had room for three gallows, which had been made up in sections, outside the prison, and silently assembled near the main entrance, without so much as a single blow of an axe being heard. As the rest of the prisoners slept the heavy sleep of those with an eternity on their hands, the commandant, priest and guards accompanied the five prisoners in single file to the place of execution. The condemned men were offered the consolation of a priest but all refused. There being only three gallows, they had to hang them in two batches... The sack was thrown over their heads and the stools kicked from under them. The condemned in Russia were not yet accorded the merciful death of the trapdoor, but a slower one, by strangulation." (15)

When the St Petersburg newspaper carrying the news of Ulyanov's execution reached his family in Simbirsk. His 17 year-old brother, Lenin, was reported as saying "I'll make them pay for this! I swear it." However, he was not tempted to become a terrorist like his brother. According to his sister Maria, Lenin said: "No , we shall not take take that road (the one chosen by Alexander) our road must be different." (16) Lenin was later to write: "The utter uselessness of terror is clearly shown by the experience of the Russian revolutionary movement... Individual acts of terrorism create only a short-lived sensation, and lead in the long run to an apathy, and the passive awaiting of yet another sensation." (17)

Joel Carmichael has pointed out, Lenin and other young intellectuals in Russia turned away from terrorism to the ideas of Karl Marx: "Perhaps the chief appeal that Marxism held for the Russian intelligentsia, even more so than for the intellectuals of other countries, was its combination of a powerful messianic yearning with an appearance of scientific methodology. It offered youthful enthusiasts the best of both worlds. Their ardent desire to change the world was fortified by sound, or seemingly sound, scientific reasons as to why this was not only possible, but was, even more seductively, inevitable. As far as Russia was concerned, Marxism may be summed up as the contention that Russian history is a part of world history and that, because of this, Russia must pass through capitalism in order to reach the future socialist society. It was not the peasantry, Marxists thought, that would be able to lead the march to socialism, but the industrial working class. Terrorism had to be abandoned as a tactic that was both futile and, in view of the objectively developing social forces, superfluous. The main task of the revolutionary leaders was to be the creation of a disciplined working-class party to conduct Russia into the promised land." (18)

Lenin is exiled to Siberia

As the brother of a state criminal, attempts were made to stop Lenin from entering university. Eventually he was allowed to study law at Kazan University. While at university Lenin became involved in politics. After one protest demonstration he was arrested and taken to the local police station. One of the police officers asked: "Why are you rebelling, young man? After all, there is a wall in front of you." Lenin confidently replied: "The wall is tottering, you only have to push it for it to fall over." (19)

Lenin was now expelled from Kazan University and so he went to St. Petersburg and studied as an external student. After passing his law exams in 1891, Lenin started practising law in Samara. He studied the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels but complained that he could find "no one in Samara who was interested in Marxist theory although there was a small group of Narodniki (populists) and a fairly good, illegal library... but there was no one with whom he could carry on intelligent theoretical discussions." (20)

Lenin returned to St. Petersburg in 1893. He continued his involvement in politics and in 1895 went to Switzerland to meet George Plekhanov, Pavel Axelrod, Vera Zasulich and Lev Deich and other members of the Liberation of Labour group. He was especially impressed with Plekhanov who "had begun almost single-handed a new tradition in Russian radicalism". The feelings were mutual: "Plekhanov was overjoyed at the evidence of the growth of Marxism in his country. He predicted for his young pupil a great future as a working-class leader." (21)

On 25th December, 1894, Alexander Potresov met Lenin for the first time. Lenin was 24 years old but he looked much older: "His face was worn; his entire head bald, except for some thin hair at the temples, and he had a scanty reddish beard. His squinting eyes peered slyly from under his brows... My opinion was that he undoubtedly represented a great force." (21a)

When Lenin returned to Russia in 1896, and along with a group of friends, including Jules Martov, he formed the Union of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class. During a textile strike that year they published leaflets and appeals in support of the strikers. Their main demand was for a reduction in the working day from thirteen hours to ten-and-a-half. The first strike ended in failure but a second strike, that lasted from January to March, 1897, was a success and the employers agreed to a shorter working day. (22)

The secret police was aware of Lenin activities and was arrested and sentenced to three years internal exile in Siberia. His close colleague, Nadezhda Krupskaya, joined Lenin in Shushenskoye and they married in July, 1898. While living in exile Lenin wrote The Development of Capitalism in Russia, The Tasks of Russian Social Democrats, as well as articles for various socialist journals. Lenin and Krupskaya also translated from English to Russian, The Theory and Practice of Trade Unionism by Sidney Webb and Beatrice Webb. (23)

Social Democratic Labour Party

Released in February, 1900, Lenin, and Jules Martov decided to leave Russia. They moved to Geneva where they joined up with George Plekhanov, Pavel Axelrod and other members of the Liberation of Labour to publish Iskra (Spark). The paper was named after a passage from a poem: "The spark will kindle a flame". Others who joined the venture included Alexander Potresov, Gregory Zinoviev, Leon Trotsky, Vera Zasulich, Yuri Piatakov and Evgenia Bosh. Clara Zetkin, a German revolutionary, arranged for Iskra to be printed in Leipzig. According to Trotsky the group "advocated a centralized revolutionary party". (24)

In the first forty-five issues of the journal Martov wrote thirty-nine articles and Lenin thirty-two; while Plekhanov had done twenty-four, Potresov eight, Zasulich six, Axelrod four and Trotsky two. Rosa Luxemburg and Alexander Parvus also wrote the occasional article. "Lenin and Martov had done all the technical editorial work. Though their emphases and approaches had been distinct, there had been no shadow of political difference." (24a)

The newspaper now became the official journal of the Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP), an organization that attempted to unite all socialist groups in favour of the overthrow of the autocracy in Russia. In their manifesto, composed by Peter Struve, the SDLP argued: "The principle and immediate goal of the Party is to achieve political freedom. The Social Democrats strive for the very aim already defined by the heroic fighters of the People Will. The ways and means of Social Democracy are, however, different. Their selection is determined by its avowed will to become and remain the class movement of the organized working masses." (25)

In March, 1902 Lenin published a pamphlet, What Is To Be Done? where he argued for a party of professional revolutionaries dedicated to the overthrow of Tsarism. "Socialist consciousness cannot exist among the workers. This can be introduced only from without. The history of all countries shows that by its unaided efforts the working-class can only develop a trade-union consciousness, that is to say, a conviction of the necessity to form trade unions, struggle with the employers, obtain from the government this or that law required by the workers." (26)

In the pamphlet Lenin attacked other socialist theorists such as Victor Chernov, Peter Struve and Eduard Bernstein. Lenin made it clear that he had no confidence in the trade union movement to develop a mass movement of the proletariat. "Education - or more correctly, indoctrination - was the key. The masses must be educated into class consciousness and a proper awareness of the battle ahead." However, even with this level of political awareness, nothing could be achieved without "the leadership of an elite, scientifically informed, Marxist intelligentsia, whose role was to organise in the vanguard, in the utmost secrecy". Lenin was convinced that true political struggle had to be "orchestrated by a a group of hardened, experienced professionals; they would do the thinking for the masses." (27)

As Adam B. Ulam has pointed out: "Lenin calmly says that socialism has but little to do with the workers. Marx and Engels were middle-class intellectuals. In Russia socialist ideas have come always from upper and middle-class intellectuals... As yet this party existed only in Lenin's mind. It was to be composed of professional revolutionaries, but it was not a mere conspiracy. It was to enlist intellectuals, indeed from among them were to be sought its leaders, but it was to avoid the intellectuals' vices of continuous doctrinal dispute, indecision, humanitarian scruples, and the like... The Party is to be like an army, but an army needs a general... Unconsciously Lenin has sketched a blueprint for a dictatorship." (28)

In April 1902, Lenin and his wife moved to London and rented two rooms at 30 Holford Square. They were both paid a small wage by the Social Democratic Labour Party but had only ten shillings to live on after they had paid their rent. The couple complained that British food "turned their Russian stomachs". They also disliked the weather, with its drizzling rain and endless fogs and Lenin told George Plekhanov that "at first glance, it makes a foul impression". (29) His wife pointed out that Lenin spent most of his time in the excellent library of the British Museum. (30)

Lenin eventually got to like living in England. He especially enjoyed the countryside and his favourite haunt was Primrose Hill. From the top of the hill he could see all of London. He also enjoyed going to the theatre and in February 1903, he wrote to his mother commenting that "the winter is exceptionally good, mild, and (so far) little rain or fog... Our life goes on as usual, quietly and modestly. The other day... we went to a good concert and were very pleased with it, especially with Tchaikovsky's Pathétique sympathy." (31)

Nadezhda Krupskaya commented that Lenin spent time observing the class differences in London. "He liked the bustle of this huge commercial city. The quiet squares, the detached houses, with their separate entrances and shining windows adorned with greenery, the drives frequented only by highly polished broughams, were much in evidence, but tucked away nearby, the mean little streets, inhabited by the London working people, where lines with washing hung across the street, and pale children played in the gutter - these sites could not be seen from the bus top. In such districts we went on foot, and observing these glaring contrasts of wealth and poverty, Ilyich would mutter between clenched teeth, in English! Two nations!" (32)

At the Second Congress of the Social Democratic Labour Party held in London in 1903, there was a dispute between Lenin and Julius Martov over the future of the SDLP. Alexander Potresov later argued: "At first it seemed to us that we were a group of comrades: that not just ideas united us, but also friendship and complete mutual trust... But the quiet friendship and calm that had reigned in our ranks had disappeared quickly. The person responsible for this change was Lenin. As time went on, his despotic character became more and more evident. He could not bear any opinion different from his own... His opponent would become a personal enemy, in the struggle with whom all tactics were permissible. Vera Zasulich was the first to notice this characteristic in Lenin. At first she detected it in his attitude towards people with different ideas - the liberals, for example. But gradually it began to appear also in his attitude towards his closest comrades... At first we had been a united family, a group of people who had committed themselves to the Revolution. But we had gradually turned into an executive organ in the hands of a strong man with a dictatorial character." (33)

Alexander Schottmann was attending his first SDLP congress and compared the impact that Lenin and Martov had on him: "Martov resembled a poor Russian intellectual. His face was pale, he had sunken cheeks; his scant beard was untidy. His glasses barely remained on his nose. His suit hung on him as on a clothes hanger. Manuscripts and pamphlets protruded from all his pockets. He was stooped, one of his shoulders was higher than the other. He had a stutter. His outward appearance was far from attractive. But as soon as he began a fervent speech all these outer faults seemed to vanish, and what remained was his colossal knowledge, his sharp mind, and his fanatical devotion to the cause of the working-class."

Schottmann was also impressed with Lenin in his disagreements with George Plekhanov. "I remember very vividly that immediately after his first address I was won over to his side, so simple, clear, and convincing was his manner of speaking... When Plekhanov spoke, I enjoyed the beauty of his speech, the remarkable incisiveness of his words. But when Lenin arose in opposition, I was always on Lenin's side. Why? I cannot explain it to myself. But so it was, and not only with me, but with my comrades." (34)

Lenin argued for a small party of professional revolutionaries with a large fringe of non-party sympathizers and supporters. Martov disagreed believing it was better to have a large party of activists. Leon Trotsky commented that "the split came unexpectedly for all the members of the congress. Lenin, the most active figure in the struggle, did not foresee it, nor had he ever desired it. Both sides were greatly upset by the course of events." (35)

Although Martov won the vote 28-23 on the paragraph defining Party membership. With the support of Plekhanov, Lenin won on almost every other important issue. His greatest victory was over the issue of the size of the Iskra editorial board to three, himself, Plekhanov and Martov. This meant the elimination of Pavel Axelrod, Alexander Potresov and Vera Zasulich - all of whom were "Martov supporters in the growing ideological war between Lenin and Martov". (36)

Trotsky argued that "Lenin's behaviour seemed unpardonable to me, both horrible and outrageous. And yet, politically it was right and necessary, from the point of view of organization. The break with the older ones, who remained in the preparatory stages, was inevitable in any case. Lenin understood this before anyone else did. He made an attempt to keep Plekhanov by separating him from Zasulich and Axelrod. But this, too, was quite futile, as subsequent events soon proved." (37)

One of the main arguments was over the subject of democracy in the party. Plekhanov argued in favour of what he and Lenin called the "dictatorship of the proletariat". This meant "the suppression of all social movements which directly or indirectly threaten the interests of the proletariat". When delegates complained about this new development Plekhanov replied by saying that "every democratic principle must be appraised not separately and abstractly, but in its relation to what may be regarded as the basic principle of democracy". The success of the revolution is the supreme law and that might mean the rejection of the idea of "universal suffrage". Lenin applauded when he argued: "If the people, in a surge of revolutionary enthusiasm, should elect a good parliament, we should endeavour to make it a long parliament. If the elections miscarry, we shot try to disperse it, not in two years, but in two weeks." (38)

As Lenin and Plekhanov won most of the votes, their group became known as the Bolsheviks (after bolshinstvo, the Russian word for majority), whereas Martov's group were dubbed Mensheviks (after menshinstvo, meaning minority). Those who became Bolsheviks included Gregory Zinoviev, Anatoli Lunacharsky, Joseph Stalin, Mikhail Lashevich, Nadezhda Krupskaya, Mikhail Frunze, Alexei Rykov, Yakov Sverdlov, Lev Kamenev, Maxim Litvinov, Vladimir Antonov, Felix Dzerzhinsky, Vyacheslav Menzhinsky, Kliment Voroshilov, Vatslav Vorovsky, Yan Berzin and Gregory Ordzhonikidze.

Leon Trotsky supported Julius Martov. So also did Pavel Axelrod, Lev Deich, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, Irakli Tsereteli, Moisei Uritsky, Vera Zasulich, Alexander Potresov, Noi Zhordania and Fedor Dan. Trotsky argued in My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (1930): "How did I come to be with the 'softs' at the congress? Of the Iskra editors, my closest connections were with Martov, Zasulich and Axelrod. Their influence over me was unquestionable. Before the congress there were various shades of opinion on the editorial board, but no sharp differences. I stood farthest from Plekhanov, who, after the first really trivial encounters, had taken an intense dislike to me. Lenin's attitude towards me was unexceptionally kind. But now it was he who, in my eyes, was attacking the editorial board, a body which was, in my opinion, a single unit, and which bore the exciting name of Iskra. The idea of a split within the board seemed nothing short of sacrilegious to me." (39)

Martov refused to serve on the three-man Iskra board as he could not accept the vote of non-confidence in Axelrod, Potresov and Zasulich. Plekhanov tried to restore party harmony by reconstituting the editorial board on its old basis, with the return of Axelrod, Potresov, Martov and Zasulich. (40) Lenin refused and when Plekhanov insisted that there was no other way to restore unity, Lenin handed in his resignation and stated: "I am absolutely convinced that you will come to the conclusion that it is impossible to work with the Mensheviks." (41)

Plekhanov now began to attack Lenin and predicted that in time he would be a dictator. That he would use "the Central Committee everywhere liquidates the elements with which it is dissatisfied, everywhere seats its own creatures and, filling all the committees with these creatures, without difficulty guarantees itself a fully submissive majority at the congress. The congress, constituted of the creatures of the Central Committee, amiably cries Hurrah!, approves all its successful and unsuccessful actions, and applauds all its plans and initiatives." (42)

Another vigorous attack on Lenin came from Trotsky who described him as a "despot and terrorist who sought to turn the Central Committee of the Party into a Committee of Public Safety - in order to be able to play the role of Robespierre." If Lenin ever took power "the entire international movement of the proletariat would be accused by a revolutionary tribunal of moderatism and the leonine head of Marx would be the first to fall under the guillotine." He added that when Lenin spoke of the dictatorship of the proletariat, he really meant "a dictatorship over the proletariat". (43)

Lenin came under attack from the Marxist philosopher, Rosa Luxemburg. In 1904 she published Organizational Questions of the Russian Democracy, where she argued: "Lenin’s thesis is that the party Central Committee should have the privilege of naming all the local committees of the party. It should have the right to appoint the effective organs of all local bodies from Geneva to Liege, from Tomsk to Irkutsk. It should also have the right to impose on all of them its own ready-made rules of party conduct... The Central Committee would be the only thinking element in the party. All other groupings would be its executive limbs." Luxemburg disagreed with Lenin's views on centralism and suggested that any successful revolution that used this strategy would develop into a communist dictatorship. (44)

In December, 1904, Lenin launched his own newspaper, Vperyod (Forward). Lenin wrote to Essen Knuniyants: "All the Bolsheviks are rejoicing... At last we have broken up the cursed dissension and are working harmoniously with those who want to work and not to create scandals! A good group of contributors has been got together; there are fresh forces... The Central Committee which betrayed us has lost all credit... The Bolshevik Committees are joining together; they have already chose a Bureau and now the organ will completely unite them.... Do not lose heart. We are all reviving now and will continue to revive... Above all be cheerful. Remember, you and I are not so old yet... everything is still before us." (45)

Lenin and the 1905 Russian Revolution

1904 was a bad year for Russian workers. Prices of essential goods rose so quickly that real wages declined by 20 per cent. When four members of the Assembly of Russian Workers of St Petersburg, were dismissed at the Putilov Iron Works in December, Father Georgi Gapon tried to intercede for the men who lost their jobs. This included talks with the factory owners and the governor-general of St Petersburg. When this failed, Gapon called for his members in the Putilov Iron Works to come out on strike. (46)

Father Georgi Gapon demanded: (i) An 8-hour day and freedom to organize trade unions. (ii) Improved working conditions, free medical aid, higher wages for women workers. (iii) Elections to be held for a constituent assembly by universal, equal and secret suffrage. (iv) Freedom of speech, press, association and religion. (v) An end to the war with Japan. By the 3rd January 1905, all 13,000 workers at Putilov were on strike, the department of police reported to the Minister of the Interior. "Soon the only occupants of the factory were two agents of the secret police". (47)

The strike spread to other factories. By the 8th January over 110,000 workers in St. Petersburg were on strike. Father Gapon wrote that: "St Petersburg seethed with excitement. All the factories, mills and workshops gradually stopped working, till at last not one chimney remained smoking in the great industrial district... Thousands of men and women gathered incessantly before the premises of the branches of the Workmen's Association." (48)

Tsar Nicholas II became concerned about these events and wrote in his diary: "Since yesterday all the factories and workshops in St. Petersburg have been on strike. Troops have been brought in from the surroundings to strengthen the garrison. The workers have conducted themselves calmly hitherto. Their number is estimated at 120,000. At the head of the workers' union some priest - socialist Gapon. Mirsky (the Minister of the Interior) came in the evening with a report of the measures taken." (49)

Gapon drew up a petition that he intended to present a message to Nicholas II: "We workers, our children, our wives and our old, helpless parents have come, Lord, to seek truth and protection from you. We are impoverished and oppressed, unbearable work is imposed on us, we are despised and not recognized as human beings. We are treated as slaves, who must bear their fate and be silent. We have suffered terrible things, but we are pressed ever deeper into the abyss of poverty, ignorance and lack of rights." (50)

The petition contained a series of political and economic demands that "would overcome the ignorance and legal oppression of the Russian people". This included demands for universal and compulsory education, freedom of the press, association and conscience, the liberation of political prisoners, separation of church and state, replacement of indirect taxation by a progressive income tax, equality before the law, the abolition of redemption payments, cheap credit and the transfer of the land to the people. (51)

Over 150,000 people signed the document and on 22nd January, 1905, Father Georgi Gapon led a large procession of workers to the Winter Palace in order to present the petition. The loyal character of the demonstration was stressed by the many church icons and portraits of the Tsar carried by the demonstrators. Alexandra Kollontai was on the march and her biographer, Cathy Porter, has described what took place: "She described the hot sun on the snow that Sunday morning, as she joined hundreds of thousands of workers, dressed in their Sunday best and accompanied by elderly relatives and children. They moved off in respectful silence towards the Winter Palace, and stood in the snow for two hours, holding their banners, icons and portraits of the Tsar, waiting for him to appear." (52)

Harold Williams, a journalist working for the Manchester Guardian, also watched the Gapon led procession taking place: "I shall never forget that Sunday in January 1905 when, from the outskirts of the city, from the factory regions beyond the Moscow Gate, from the Narva side, from up the river, the workmen came in thousands crowding into the centre to seek from the tsar redress for obscurely felt grievances; how they surged over the snow, a black thronging mass." (53) The soldiers machine-gunned them down and the Cossacks charged them. (54)

The killing of the demonstrators became known as Bloody Sunday and it has been argued that this event signalled the start of the 1905 Revolution. That night the Tsar wrote in his diary: "A painful day. There have been serious disorders in St. Petersburg because workmen wanted to come up to the Winter Palace. Troops had to open fire in several places in the city; there were many killed and wounded. God, how painful and sad." (55)

The massacre of an unarmed crowd undermined the standing of the autocracy in Russia. The United States consul in Odessa reported: "All classes condemn the authorities and more particularly the Tsar. The present ruler has lost absolutely the affection of the Russian people, and whatever the future may have in store for the dynasty, the present tsar will never again be safe in the midst of his people." (56)

The day after the massacre all the workers at the capital's electricity stations came out on strike. This was followed by general strikes taking place in Moscow, Vilno, Kovno, Riga, Revel and Kiev. Other strikes broke out all over the country. Pyotr Sviatopolk-Mirsky resigned his post as Minister of the Interior, and on 19th January, 1905, Tsar Nicholas II summoned a group of workers to the Winter Palace and instructed them to elect delegates to his new Shidlovsky Commission, which promised to deal with some of their grievances. (57)

Lenin, who had been highly suspicious of Father Gapon, admitted that the formation of Assembly of Russian Workers of St Petersburg and the occurrence of Bloody Sunday, had made an important contribution to the development of a radical political consciousness: "The revolutionary education of the proletariat made more progress in one day than it could have made in months and years of drab, humdrum, wretched existence." (58)

On 27th June, 1905, sailors on the Potemkin battleship, protested against the serving of rotten meat infested with maggots. The captain ordered that the ringleaders to be shot. The firing-squad refused to carry out the order and joined with the rest of the crew in throwing the officers overboard. The mutineers killed seven of the Potemkin's eighteen officers, including Captain Evgeny Golikov. They organized a ship's committee of 25 sailors, led by Afanasi Matushenko, to run the battleship. (59)

A delegation of the mutinous sailors arrived in Geneva with a message addressed directly to Father Gapon. He took the cause of the sailors to heart and spent all his time collecting money and purchasing supplies for them. He and their leader, Afanasi Matushenko, became inseparable. "Both were of peasant origin and products of the mass upheaval of 1905 - both were out of place among the party intelligentsia of Geneva." (60)

The Potemkin Mutiny spread to other units in the army and navy. Industrial workers all over Russia withdrew their labour and in October, 1905, the railwaymen went on strike which paralyzed the whole Russian railway network. These events became known as the 1905 Revolution. These industrial disputes developed into a general strike. Leon Trotsky later recalled: "After 10th October 1905, the strike, now with political slogans, spread from Moscow throughout the country. No such general strike had ever been seen anywhere before. In many towns there were clashes with the troops." (61)

Later that month, Trotsky and other Mensheviks established the St. Petersburg Soviet. On 26th October the first meeting of the Soviet took place in the Technological Institute. It was attended by only forty delegates as most factories in the city had time to elect the representatives. It published a statement that claimed: "In the next few days decisive events will take place in Russia, which will determine for many years the fate of the working class in Russia. We must be fully prepared to cope with these events united through our common Soviet." (62)

The Bolsheviks had little influence in the Soviets. Lenin regarded this "undisciplined organism as a dangerous rival to the Party, a spontaneous proletarian assembly which a small group of 'professional revolutionists' would not be able to control." (63) Lenin urged his supporter to become involved in the revolution. "It requires furious energy and more energy. I am appalled, truly appalled to see that more than half a year has been spent in talk about bombs - and not a single bomb has yet been made... Go to the youth. Organize at once and everywhere fighting brigades among students, and particularly among workers. Let them arm themselves immediately with whatever weapons they can obtain - a knife, a revolver, a kerosene-soaked rag for setting fires." (64)

Lenin: 1906-1912

Lenin also spent a great deal of time finding ways of raising money for the party. He secured large donations from Maxim Gorky and Savva Morozov, the Moscow millionaire textile manufacturer. Leonid Krassin, a leading Bolshevik, approached Morozov and explained Lenin's virtues as a radical political leader. He commented: "I know all about that; I agree; Lenin is a man of vision. How much does he want?" Krassin replied: "As much as possible". Morozov arranged to give 1,000 rubles a month?" (65)

This was not the main source of income. The armed hold-ups of Bolsheviks gangs provided much more. One raid on the Tiflis Post Office raised 250,000 roubles. The gang used bombs during the robbery and several people were killed. When George Plekhanov, one of the leaders of the Mensheviks, heard that the Bolsheviks were behind the robbery he declared: "The whole affair is so outrageous that it is really high time for us to break off all relations with the Bolsheviks." Lenin justified the action with the words: "In politics there is only one principle and one truth: what profits my opponent hurts me and vice versa." (66)

Lenin, and his two loyal assistants, Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev, used this money to print revolutionary literature and newspapers such as Zvezda. Some money was used to gain control some of the unions that were emerging in Russia's main industrial cities. One of Lenin's agents, Roman Malinovsky, was elected as general secretary of the St Petersburg Metalworkers' Union and became one of his most trusted Bolshevik agents in Russia. (67)

In 1911, Lenin, Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, David Riazanov, Anatoli Lunacharsky and other Bolsheviks moved to France and settled in a small village just outside of Paris. He was also joined by Yuri Piatakov and Evgenia Bosh. However, under the influence of Bosh, Piatakov fell out with Lenin on the "national question". As Kathy Fairfax, the author of Comrades in Arms: Bolshevik Women in the Russian Revolution (1999) has pointed out: "With her Ukrainian experience Bosh felt that nationalism of proletarian internationalism while Lenin considered that the nationalism of the oppressed had a revolutionary potential, especially in the tsarist empire." (68)

They were joined by Inessa Armand, the former wife of a wealthy businessman, who helped Lenin set up a Bolshevik Party School where agents were trained before returning to Russia. Yekaterina Kuskova described her as "beautiful, elegant - not comparable in any way with the dowdy Krupskaya... when the Bolshevik school for workers opened near Paris, Lenin made Armand give lectures to the workers - he always attended them." According to Alexandra Kollontai, Krupskaya "knew Lenin was very attracted to Inessa... and was well aware of what was going on." (69)

Helen Rappaport, the author of Conspirator: Lenin in Exile (2009) has pointed out: "If her husband's sexual needs could only be fulfilled elsewhere then the consolation to Nadya was that it was at least with a fellow Bolshevik and a woman she liked... It was rare indeed for Bolshevik women, aside perhaps from Nadya, or Elena Stasova in St Petersburg, to be given a leading role in any major party matters and, when they were, their contribution was largely mundane. Lenin's unequivocal favouritism of Inessa was reinforced when he asked her to take over the running of the Central Committee's Foreign Bureau that autumn. With her proven linguistic skills, Inessa would play a crucial role in liasing with emigrant groups, eventually across thirty-seven European cities, a function previously fulfilled in the main by Nadya." (70)

Bertram D. Wolfe has argued: "She (Inessa Armand) had a wider culture than any other woman in Lenin's circle, a deep love of music, above all of Beethoven, who became Lenin's favourite too. She played the piano like a virtuoso, was fluent in five languages, was enormously serious about Bolshevism and work among women, and possessed personal charm and an intense love of life to which almost all who wrote of her testify." Wolfe claims that Lenin's love of Armand caused problems with other revolutionaries. Angelica Balabanoff told Wolfe: "I did not warm to Inessa. She was pedantic, a one hundred per cent Bolshevik in the way she dressed (always in the same severe style), in the way she thought, and spoke. She spoke a number of languages fluently, and in all of them repeated Lenin verbatim." (71)

Roman Malinovsky

In January, 1912, Lenin organised a Russian Social Democratic Labour Party conference In Prague. Lenin's major rivals, Jules Martov, George Plekhanov, Pavel Axelrod and Leon Trotsky, were all invited but they all declined to take part. Some of the delegates protested that the meeting was unrepresentational and Gregory Ordzhonikidze suggested that the RSDLP should be under the control of people living in Russia instead of by "out of touch émigrés". Despite this opposition Lenin was able to get all his motions carried unanimously. The Prague meeting had, in Lenin's own words "constituted itself as the supreme and legitimate assembly of the entire RSDLP". (72)

At the Prague conference in 1912 Lenin suggested that Roman Malinovsky should join the Bolshevik Central Committee. Nickolai Bukharin objected to the proposal arguing that he was convinced that he was an Okhrana agent. He pointed out that in April 1910, Malinovsky and a group of his comrades were arrested. He was soon released but the rest remained in prison. Soon afterwards there was a wave of arrests among the Bolsheviks. This included Bukharin, who while in prison met several men who believed Malinovsky of being responsible for their arrest. (73)

Bukharin's objections were rejected by Lenin and advocated that Malinovsky should also be a Bolshevik candidate for the Duma. After being elected he became known as an eloquent and forceful orator. Before making his speeches he sent copies to Lenin and S. P. Beletsky, the director of Okhrana. It was later revealed that he was Okhrana's best-paid agent, earning 8,000 rubles a year, 1,000 more than the Director of the Imperial Police. (74)

After being elected in October, 1912, Roman Malinovsky became the leader of the group of six Bolshevik deputies. Lenin argued: "For the first time among ours in the Duma there is an outstanding worker-leader. He will read the Declaration (the political declaration of the Social Democratic fraction on the address of the Prime Minister). This time it's not another Alexinsky. And the results - perhaps not immediately - will be great." (75)

Malinovsky was now in a position to spy on Lenin. This included supplying Okhrana with copies of his letters. In a letter dated 18th December, 1912, S. E. Vissarionov, the Assistant Director of Okhrana, wrote to Nikolay Maklakov, the Minister of the Interior: "The situation of the Fraction is now such that it may be possible for the six Bolsheviks to be induced to act in such a way as to split the Fraction into Bolsheviks and Mensheviks. Lenin supports this. See his letter (supplied by Malinovsky)". (76)

When Elena Troyanovsky was arrested in 1913 her husband, Aleksandr A. Troyanovsky, wrote a letter claiming that if she was not released he would expose the double agent in the leadership of the Bolsheviks. S. P. Beletsky later testified that when he showed this letter to Malinovsky he "became hysterical" and demanded that she was released. In order that he remained as a spy Beletsky agreed to do this. Troyanovsky took this information to Nickolai Bukharin and when Lenin was told about this he called their actions as being worse than treason. Troyanovsky responded by leaving the Bolsheviks. Instead of carrying out an investigation into Malinovsky, Lenin launched an attack on Julius Martov and Fedor Dan, who he accused of acting like "gossipy old women". (77)

Bertram D. Wolfe argued that in 1913: "He (Malinovsky) was entrusted with setting up a secret printing plant inside Russia, which naturally did not remain secret for long. Together with Yakovlev he helped start a Bolshevik paper in Moscow. It, too, ended promptly with the arrest of the editor. Inside Russia, the popular Duma Deputy traveled to all centers. Arrests took place sufficiently later to avert suspicion from him... The police raised his wage from five hundred to six hundred, and then to seven hundred rubles a month." (78)

Nadezhda Krupskaya later explained: "Vladimir Ilyich thought it utterly impossible for Malinovsky to have been an agent provocateur. These rumors came from Menshevik circles... The commission investigated all the rumors but could not obtain any definite proof of the charge. Only once did a doubt flash across his mind. I remember one day in Poronino, we were returning from the Zinoviews and talking about these rumours. All of sudden Ilyich stopped on the little bridge we were crossing and said: 'It may be true!' - and his face expressed anxiety. 'What are you talking about, it's nonsence'. Ilyich calmed down and began to abuse the Mensheviks, saying that they were unscrupulous as to the means they employed in the struggle against the Bolsheviks." (79)

In 1913 Lenin and Nadezhda Krupskaya moved to Galicia in Austria. He organized a conference of Bolshevik leaders in Zakopane in August. It was later discovered that of the twenty-two men who attended, five, including Roman Malinovsky, were Okhrana agents. In the autumn of 1913, Inessa Armand joined Lenin in Galicia. According to Angelica Balabanoff, Inessa and Lenin were now lovers: "Lenin loved Inessa. There was nothing immoral in it, since Lenin told Krupskaya everything. He deeply loved music, and this Krupskaya could not give him. Inessa played beautifully his beloved Beethoven and other pieces... He had had a child by Inessa." This story is also supported by the testimony of Alexandra Kollontai. (80)

The rumours about Malinovsky continued and in June 1914 he wrote an article condemning Julius Martov and Fedor Dan, for sprending these untrue stories. "We do not believe one single word of Dan and Martov.... We don't trust Martov and Dan. We do not regard them as honest citizens. We will deal with them only as common criminals - only so, and not otherwise... If a man says, make political concessions to me, recognize me as an equal comrade of the Marxist community or I will set up a howl about rumors of the provocateur activity of Malinovsky, that is political blackmail. Against blackmail we are always and unconditionally for the bourgeois legality of the bourgeois court... Either you make a public accusation signed with your signature so that the bourgeois court can expose and punish you (there are no other means of fighting blackmail), or you remain as people branded... as slanderers by the workers." (81)

Lenin and the First World War

In February 1914, Tsar Nicholas II accepted the advice of his foreign minister, Sergi Sazonov, and committed Russia to supporting the Triple Entente. Sazonov was of the opinion that in the event of a war, Russia's membership of the Triple Entente would enable it to make territorial gains from neighbouring countries. Sazonov sent a telegram to the Russian ambassador in London asking him to make clear to the British government that the Tsar was committed to a war with Germany. "The peace of the world will only be secure on the day when the Triple Entente, whose real existence is not better authenticated than the existence of the sea serpent, shall transform itself into a defensive alliance without secret clauses and publicly announced in all the world press. On that day the danger of a German hegemony will be finally removed, and each one of us will be able to devote himself quietly to his own affairs." (82)

In the international crisis that followed the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, the Tsar made it clear that he was willing to go to war over this issue, Rasputin was an outspoken critic of this policy and joined forces with two senior figures, Sergei Witte and Pyotr Durnovo, to prevent the war. Durnovo told the Tsar that a war with Germany would be "mutually dangerous" to both countries, no matter who won. Witte added that "there must inevitably break out in the conquered country a social revolution, which by the very nature of things, will spread to the country of the victor." (83)

Witte realised that because of its economic situation, Russia would lose a war with any of its rivals. Bernard Pares met Witte and Grigori Rasputin several times in the years leading up to the First World War: "Count Witte never swerved from his conviction, firstly, that Russia must avoid the war at all costs, and secondly, that she must work for economic friendship with France and Germany to counteract the preponderance of England. Rasputin was opposed to the war for reasons as good as Witte's. He was for peace between all nations and between all religions." (84)

In August, 1914, Russian revolutionaries had a meeting in Switzerland to discuss the war. Leon Trotsky attempted to explain the level of nationalism that emerged during the first few days of the war. "The mobilization and declaration of war have veritably swept off the face of the earth all the national and social contradictions in the country". (85) Trotsky argued the workers believed that if their country conquered new colonies and markets they would enjoy higher living standards. In time of war, therefore, the workers still identified themselves with the cause of their exploiters. Julius Martov agreed with Trotsky that "their internationalism was still too weak to overcome the new flush of national patriotism which the war had produced." (86)

George Plekhanov defended the socialists of the Allied countries for their patriotism as they had to give their full support to their governments against German militarism. Nickolai Bukharin described how Lenin reacted to the speech. "Never before or after did I see such a deathly pallor on Ilyich's face. Only his eyes were burning brightly, when, in a dry, guttural voice, he started to lash his opponent sharply and forcefully." (87)

Lenin criticised the views of Trotsky, Plekhanov and Martov as being defeatest. He was appalled by the decision of most socialists in Europe to support the war effort. He was especially angry with the German Social Democratic Party (SDP) as Karl Liebknecht was the only member of the Reichstag who voted against Germany's participation in the war. He published several pamphlets on the war including The Tasks of Revolutionary Social Democracy in the European War and The War and Russian Social Democracy that were smuggled into Russia. He argued for the "tsarist monarchy to be defeated and the imperialist war turned into a European-wide civil war." (88)

Lenin argued: "The European and world war has the clearly defined character of a bourgeois, imperialist and dynastic war. A struggle for markets and for freedom to loot foreign countries, a striving to suppress the revolutionary movement of the proletariat and democracy in the individual countries, a desire to deceive, disunite, and slaughter the proletarians of all countries by setting the wage slaves of one nation against those of another so as to benefit the bourgeoisie - these are the only real content and significance of the war.The conduct of the leaders of the German Social-Democratic Party, the strongest and the most influential in the Second International (1889-1914), a party which has voted for war credits and repeated the bourgeois-chauvinist phrases of the Prussian Junkers and the bourgeoisie, is sheer betrayal of socialism." (89)

Lenin argued that "the slogan of peace is wrong - the slogan must be, turn the imperialist war into civil war." Lenin believed that a civil war in Russia would bring down the old order and enable the Bolsheviks to gain power. This brought him into conflict with Rosa Luxemburg. In 1915 Luxemburg published the highly influential pamphlet, The Crisis in the German Social Democracy. Luxemburg rejected the view of Lenin that the war would bring democracy to Russia: "It is true that socialism gives to every people the right of independence and the freedom of independent control of its own destinies. But it is a veritable perversion of socialism to regard present-day capitalist society as the expression of this self-determination of nations. Where is there a nation in which the people have had the right to determine the form and conditions of their national, political and social existence?"

In the pamphlet Rosa Luxemburg quoted Friedrich Engels as saying: “Bourgeois society stands at the crossroads, either transition to socialism or regression into barbarism.” She added: "A look around us at this moment shows what the regression of bourgeois society into barbarism means. This world war is a regression into barbarism.... The world war today is demonstrably not only murder on a grand scale; it is also suicide of the working classes of Europe. The soldiers of socialism, the proletarians of England, France, Germany, Russia, and Belgium have for months been killing one another at the behest of capital. They are driving the cold steel of murder into each other’s hearts. Locked in the embrace of death, they tumble into a common grave."

Luxemburg also pointed out that Germany was also fighting democratic states such as Britain and France: "Germany certainly has not the right to speak of a war of defence, but France and England have little more justification. They too are protecting, not their national, but their world political existence, their old imperialistic possessions, from the attacks of the German upstart." To Luxemburg, this was an imperialist war and could not be turned into a war of political liberation. (90)

According to Adam B. Ulam, the author of The Bolsheviks (1998): "Lenin in general liked Rosa for her fine revolutionary fervour, and for the fire with which she castigated the opportunists and Revisionists of the German Social Democracy." However, Lenin disliked it when she disagreed with him. The two had clashed over the issue of Polish independence. "For revolutionary propaganda he always extolled the slogan of national self-determination... but for the revolutionary organization Lenin had always demanded unity and centralization". When she questioned his views, as she did over the war, she became "a senseless fanatic". (91)

Lenin now devoted his energies to campaign to turn the war into a revolution. This included the publication of the pamphlet, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism. Lenin broke with the Marxist conception of history which saw every society passing through feudalism, then capitalism, before socialism could be established and insisted that conditions existed to make a successful revolution possible. Along with his close collaborators, Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev, Lenin arranged for the distribution of these pamphlets that urged Allied troops to turn their rifles against their officers and start a socialist revolution. (92)

Abdication of Nicholas II

By December, 1914, the Russian Army had 6,553,000 men. However, they only had 4,652,000 rifles. It has been pointed out: "Untrained troops were ordered into battle without adequate arms or ammunition. And because the Russian Army had about one surgeon for every 10,000 men, many wounded of its soldiers died from wounds that would have been treated on the Western Front. With medical staff spread out across a 500 mile front, the likelihood of any Russian soldier receiving any medical treatment was close to zero". (93)

Tsar Nicholas II decided to replace Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolayevich Romanov as supreme commander of the Russian Army fighting on the Eastern Front. He was disturbed when he received the following information from General Alexei Brusilov: "In recent battles a third of the men had no rifles. These poor devils had to wait patiently until their comrades fell before their eyes and they could pick up weapons. The army is drowning in its own blood." (94)

Surely the Germans will not get this far!.

The Tsar: But when our own army returns....?

K. J. Chamberlain, The Masses (January, 1915)

As the Tsar spent most of his time at GHQ, Alexandra Fedorovna now took responsibility for domestic policy. Rasputin served as her adviser and over the next few months she dismissed ministers and their deputies in rapid succession. In letters to her husband she called his ministers as "fools and idiots". According to David Shub "the real ruler of Russia was the Empress Alexandra". (95)

On 7th July, 1915, the Tsar wrote to his wife and complained about the problems he faced fighting the war: "Again that cursed question of shortage of artillery and rifle ammunition - it stands in the way of an energetic advance. If we should have three days of serious fighting we might run out of ammunition altogether. Without new rifles it is impossible to fill up the gaps.... If we had a rest from fighting for about a month our condition would greatly improve. It is understood, of course, that what I say is strictly for you only. Please do not say a word to anyone." (96)

In 1916 two million Russian soldiers were killed or seriously wounded and a third of a million were taken prisoner. Millions of peasants were conscripted into the Tsar's armies but supplies of rifles and ammunition remained inadequate. It is estimated that one third of Russia's able-bodied men were serving in the army. The peasants were therefore unable to work on the farms producing the usual amount of food. By November, 1916, food prices were four times as high as before the war. As a result strikes for higher wages became common in Russia's cities. (97)

As Nicholas II was supreme command of the Russian Army he was linked to the country's military failures and there was a strong decline in his support in Russia. George Buchanan, the British Ambassador in Russia, went to see the Tsar: "I went on to say that there was now a barrier between him and his people, and that if Russia was still united as a nation it was in opposing his present policy. The people, who have rallied so splendidly round their Sovereign on the outbreak of war, had seen how hundreds of thousands of lives had been sacrificed on account of the lack of rifles and munitions; how, owing to the incompetence of the administration there had been a severe food crisis."

Buchanan then went on to talk about Tsarina Alexandra Fedorovna: "I next called His Majesty's attention to the attempts being made by the Germans, not only to create dissension between the Allies, but to estrange him from his people. Their agents were everywhere at work. They were pulling the strings, and were using as their unconscious tools those who were in the habit of advising His Majesty as to the choice of his Ministers. They indirectly influenced the Empress through those in her entourage, with the result that, instead of being loved, as she ought to be, Her Majesty was discredited and accused of working in German interests." (98)

In January 1917, General Aleksandr Krymov returned from the Eastern Front and sought a meeting with Michael Rodzianko, the President of the Duma. Krymov told Rodzianko that the officers and men no longer had faith in Nicholas II and the army was willing to support the Duma if it took control of the government of Russia. "A revolution is imminent and we at the front feel it to be so. If you decide on such an extreme step (the overthrow of the Tsar), we will support you. Clearly there is no other way." Rodzianko was unwilling to take action but he did telegraph the Tsar warning that Russia was approaching breaking point. He also criticised the impact that his wife was having on the situation and told him that "you must find a way to remove the Empress from politics". (99)

The Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich shared the views of Rodzianko and sent a letter to the Tsar: "The unrest grows; even the monarchist principle is beginning to totter; and those who defend the idea that Russia cannot exist without a Tsar lose the ground under their feet, since the facts of disorganization and lawlessness are manifest. A situation like this cannot last long. I repeat once more - it is impossible to rule the country without paying attention to the voice of the people, without meeting their needs, without a willingness to admit that the people themselves understand their own needs." (100)

The First World War was having a disastrous impact on the Russian economy. Food was in short supply and this led to rising prices. By January 1917 the price of commodities in Petrograd had increased six-fold. In an attempt to increase their wages, industrial workers went on strike and in Petrograd people took to the street demanding food. On 11th February, 1917, a large crowd marched through the streets of Petrograd breaking shop windows and shouting anti-war slogans.

Petrograd was a city of 2,700,000 swollen with an influx of of over 393,000 wartime workers. According to Harrison E. Salisbury, in the last ten days of January, the city had received 21 carloads of grain and flour per day instead of the 120 wagons needed to feed the city. Okhrana, the secret police, warned that "with every day the food question becomes more acute and it brings down cursing of the most unbridled kind against anyone who has any connection with food supplies." (101)

Harold Williams, a journalist working for the Daily Chronicle reported details of serious food shortages: "All attention here is concentrated on the food question, which for the moment has become unintelligible. Long queues before the bakers' shops have long been a normal feature of life in the city. Grey bread is now sold instead of white, and cakes are not baked. Crowds wander about the streets, mostly women and boys, with a sprinkling of workmen. Here and there windows are broken and a few bakers' shops looted." (102)

It was reported that in one demonstration in the streets by the Nevsky Prospect, the women called out to the soldiers, "Comrades, take away your bayonets, join us!". The soldiers hesitated: "They threw swift glances at their own comrades. The next moment one bayonet is slowly raised, is slowly lifted above the shoulders of the approaching demonstrators. There is thunderous applause. The triumphant crowd greeted their brothers clothed in the grey cloaks of the soldiery. The soldiers mixed freely with the demonstrators." On 27th February, 1917, the Volynsky Regiment mutinied and after killing their commanding officer "made common cause with the demonstrators". (103)

The President of the Duma, Michael Rodzianko, became very concerned about the situation in the city and sent a telegram to the Tsar: "The situation is serious. There is anarchy in the capital. The Government is paralysed. Transport, food, and fuel supply are completely disorganised. Universal discontent is increasing. Disorderly firing is going on in the streets. Some troops are firing at each other. It is urgently necessary to entrust a man enjoying the confidence of the country with the formation of a new Government. Delay is impossible. Any tardiness is fatal. I pray God that at this hour the responsibility may not fall upon the Sovereign." (104)

On Friday 8th March, 1917, there was a massive demonstration against the Tsar. It was estimated that over 200,000 took part in the march. Arthur Ransome walked along with the crowd that were hemmed in by mounted Cossacks armed with whips and sabres. But no violent suppression was attempted. Ransome was struck, chiefly, by the good humour of these rioters, made up not simply of workers, but of men and women from every class. Ransome wrote: "Women and girls, mostly well-dressed, were enjoying the excitement. It was like a bank holiday, with thunder in the air." There were further demonstrations on Saturday and on Sunday soldiers opened fire on the demonstrators. According to Ransome: "Police agents opened fire on the soldiers, and shooting became general, though I believe the soldiers mostly used blank cartridges." (105)

Morgan Philips Price, a journalist working in Petrograd, with strong left-wing opinions, wrote to his aunt, Anna Maria Philips, claiming that the country was on the verge of revolution: "Most exciting times. I knew this was coming sooner or later but did not think it would come so quickly... Whole country is wild with joy, waving red flags and singing Marseillaise. It has surpassed my wildest dreams and I can hardly believe it is true. After two-and-half years of mental suffering and darkness I at last begin to see light. Long live Great Russia who has shown the world the road to freedom. May Germany and England follow in her steps." (106)

On 10th March, 1917, the Tsar had decreed the dissolution of the Duma. The High Command of the Russian Army now feared a violent revolution and on 12th March suggested that Nicholas II should abdicate in favour of a more popular member of the royal family. Attempts were now made to persuade Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich to accept the throne. He refused and the Tsar recorded in his diary that the situation in "Petrograd is such that now the Ministers of the Duma would be helpless to do anything against the struggles the Social Democratic Party and members of the Workers Committee. My abdication is necessary... The judgement is that in the name of saving Russia and supporting the Army at the front in calmness it is necessary to decide on this step. I agreed." (107)

Prince George Lvov, was appointed the new head of the Provisional Government. Members of the Cabinet included Pavel Milyukov (leader of the Cadet Party), was Foreign Minister, Alexander Guchkov, Minister of War, Alexander Kerensky, Minister of Justice, Mikhail Tereshchenko, a beet-sugar magnate from the Ukraine, became Finance Minister, Alexander Konovalov, a munitions maker, Minister of Trade and Industry, and Peter Struve, Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Prince Lvov allowed all political prisoners to return to their homes. Joseph Stalin arrived at Nicholas Station in St. Petersburg with Lev Kamenev and Yakov Sverdlov on 25th March, 1917. The three men had been in exile in Siberia. Stalin's biographer, Robert Service, has commented: "He was pinched-looking after the long train trip and had visibly aged over the four years in exile. Having gone away a young revolutionary, he was coming back a middle-aged political veteran." (108)

The exiles discussed what to do next. The Bolshevik organizations in Petrograd were controlled by a group of young men including Vyacheslav Molotov and Alexander Shlyapnikov who had recently made arrangements for the publication of Pravda, the official Bolshevik newspaper. The young comrades were less than delighted to see these influential new arrivals. Molotov later recalled: "In 1917 Stalin and Kamenev cleverly shoved me off the Pravda editorial team. Without unnecessary fuss, quite delicately." (109)

The Petrograd Soviet recognized the authority of the Provisional Government in return for its willingness to carry out eight measures. This included the full and immediate amnesty for all political prisoners and exiles; freedom of speech, press, assembly, and strikes; the abolition of all class, group and religious restrictions; the election of a Constituent Assembly by universal secret ballot; the substitution of the police by a national militia; democratic elections of officials for municipalities and townships and the retention of the military units that had taken place in the revolution that had overthrown Nicholas II. Soldiers dominated the Soviet. The workers had only one delegate for every thousand, whereas every company of soldiers might have one or even two delegates. Voting during this period showed that only about forty out of a total of 1,500, were Bolsheviks. Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries were in the majority in the Soviet.

The Provisional Government accepted most of these demands and introduced the eight-hour day, announced a political amnesty, abolished capital punishment and the exile of political prisoners, instituted trial by jury for all offences, put an end to discrimination based on religious, class or national criteria, created an independent judiciary, separated church and state, and committed itself to full liberty of conscience, the press, worship and association. It also drew up plans for the election of a Constituent Assembly based on adult universal suffrage and announced this would take place in the autumn of 1917. It appeared to be the most progressive government in history. (110)

Lenin's Sealed Train

Lenin was living in Zurich and he did not hear this news until the 15th March. A group of about twenty Russian exiles arrived at Lenin's home to discuss this important event. Lenin's wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, explained: "From the moment the news of the February revolution came, Ilyich burned with eagerness to go to Russia. England and France would not for the world have allowed the Bolsheviks to pass through to Russia... As there was no legal way it was necessary to travel illegally. But how?" (110a)

Aware that the British and French would never allow him a transit visa to Russia through Allied territory in Europe. It was suggested that he should try to return via England under a false passport, but it was decided that this was far too risky and if he was arrested he would be probably interned for the duration of the war. On 19th March 1917 a meeting of socialists was held to discuss the issue. The German socialist Willi Münzenberg was there and later reported that Lenin paced up and down the room declaring, "we must go at all costs". Julius Martov suggested that the best chance would be to send word to the Petrograd Soviet, asking them to offer the Germans repatriation of German prisoners in exchange for the group's safe conduct home via Germany. (110b)

The Swiss socialist, Robert Grimm, who Lenin had described as a "detestable centrist", offered to negotiate with the German government in order to obtain a safe passage to Russia. He pointed out that Germany had been spending a great deal of money in producing revolutionary anti-war propaganda in Russia since 1915, in the hope of engineering a withdrawal from the war. This would enable German troops on the Eastern Front to be diverted to the western campaign against Britain and France. Grimm began talks with Count Gisbert von Romberg, the German ambassador in Berne. (110c)

Alexander Parvus also arrived in Switzerland. The former German Social Democrat who had originally helped to fund Iskra, the Russian revolutionary newspaper, had now gone over to the German government, operating as an arms contractor and recruiter for the war effort. he had been heavily involved in the German propaganda drive among tsarist troops to destabilize Nicholas II. Parvus made contact with Richard von Kühlmann, a minister at the German Foreign Office. (110d)

Von Kühlmann sent a message to Army Headquarters explaining the strategy of the German Foreign Office: "The disruption of the Entente and the subsequent creation of political combinations agreeable to us constitute the most important war aim of our diplomacy. Russia appeared to be the weakest link in the enemy chain, the task therefore was gradually to loosen it, and, when possible, to remove it. This was the purpose of the subversive activity we caused to be carried out in Russia behind the front - in the first place promotion of separatist tendencies and support of the Bolsheviks had received a steady flow of funds through various channels and under different labels that they were in a position to be able to build up their main organ, Pravda, to conduct energetic propaganda and appreciably to extend the originally narrow basis of their party." (110e)

Parvus made contact with General Erich Ludendorff who later admitted his involvement in his autobiography, My War Memories, 1914-1918 (1920) that he told senior officials: "Our government, in sending Lenin to Russia, took upon itself a tremendous responsibility. From a military point of view his journey was justified, for it was imperative that Russia should fall." (110f)

General Max Hoffmann, chief of the German General Staff on the Eastern Front commented: "We naturally tried, by means of propaganda, to increase the disintegration that the Russian Revolution had introduced into the Army. Some man at home who had connections with the Russian revolutionaries exiled in Switzerland came upon the idea of employing some of them in order to hasten the undermining and poisoning of the morale of the Russian Army."

Hoffmann claims that Reichstag deputy Mathias Erzberger became involved in the negotiations. "And thus it came about that Lenin was conveyed through Germany to Petrograd in the manner that afterwards transpired. In the same way as I send shells into the enemy trenches, as I discharge poison gas at him, I, as an enemy, have the right to employ the expedient of propaganda against his garrisons." (110g)

Paul Levi, a close associate of Rosa Luxemburg, and a member of the German anti-war Spartacus League, handled the Berne-Zurich end of negotiations, with Karl Radek. Levi was contacted by the German Ambassador in Switzerland and asked: "How can I get in touch with Lenin? I expect final instructions any moment regarding his transportation". Lenin now negotiated the deal with the ambassador that would allow him to travel through Germany. (110h)

In his farewell message to the Swiss workers Lenin explained his analysis of the situation in Russia. "It has fallen to the lot of the Russian proletariat to begin the series of revolutions whose objective necessity was created by the imperialist world war. We know well that the Russian proletariat is less organized and intellectually less prepared for the task than the working class of other countries... Russia is an agricultural country, one of the most backward of Europe. Socialism cannot be established in Russia immediately. But the peasant character of the development of a democratic-capitalist revolution in Russia and make that a prologue to the world-wide Socialist revolution." (110i)

Lenin felt he needed the support of other socialists living in Switzerland for his journey through Germany. He sent a telegram to two French anti-war figures living in Switzerland, Romain Rolland and Henri Guilbeaux, asking them to appear in the railroad station on the day of his departure. Rolland refused and sent a message to Guilbeaux: "If you have any influence on Lenin and his friends, dissuade them from going through Germany. They will cause great damage to the pacifist movement and to themselves, for it will then be said that Zimmerwald is a German child." He then went on to quote Anatoli Lunacharsky who had described Lenin as "a dangerous and cynical adventurer". (110j)

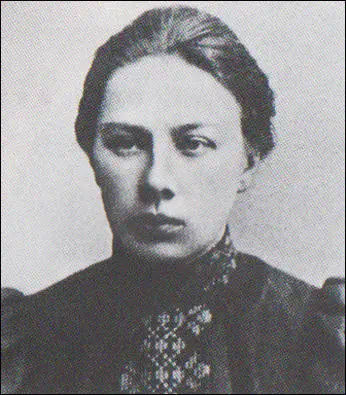

photograph is Inessa Armand (in the fur-trimmed jacket) and Nadezhda Krupskaya (in large hat).