The Russian Civil War

In 1918 a variety of different groups opposed the Bolshevik government. This included landowners who had lost their estates, factory owners who had their property nationalized, devout members of the Russian Orthodox Church who objected to the government's atheism and royalists who wanted to restore the monarchy. The closing down of the Constituent Assembly and the banning of all political parties united Socialist Revolutionaries, Mensheviks and Cadets. Others were unhappy with the acceptance of the harsh terms of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty which resulted in Russia being deprived of a third of her population, a third of her factories and three-quarters of her coal and iron producing areas. She also had to pay reparations totalling 3000 million roubles in gold. (1)

Alexander Kerensky, who had managed to escape arrest and fled to Pskov, where he rallied some loyal troops for an attempt to re-take the city. His Cossack troops managed to capture Tsarskoe Selo. According to John Reed: "The Cossacks entered Tsarskoye Selo, Kerensky himself riding a white horse and all the church-bells clamouring. There was no battle. But Kerensky made a fatal blunder. At seven in the morning he sent word to the Second Tsarskoye Selo Rifles to lay down their arms. The soldiers replied they would remain neutral, but would not disarm. Kerensky gave them ten minutes in which to obey. This angered the soldiers; for eight months they had been governing themselves by committee, and this smacked of the old regime. A few minutes later Cossack artillery opened fire on the barracks, killing eight men. From that moment there were no more 'neutral' soldiers in Tsarskoye." (2)

The next day Alexander Kerensky's soldiers were defeated by 12,000 loyal troops at Pulkovo. Kerensky narrowly escaped, and he spent the next few weeks in hiding before fleeing the country. (3) Louise Bryant was in Petrograd when news reached the city. "A huge procession marched through the streets of Petrograd to meet the returning Red Guards and soldiers." (4)

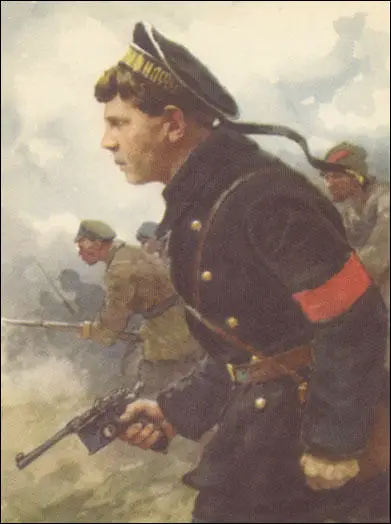

the Red Army until his death on 26th July, 1919. He was 24 years old.

After his escape from prison, General Lavr Kornilov and his supporters made their way to the Don region, which was controlled by Cossacks. Here they linked up with General Mikhail Alekseev. Kornilov became the military commander of the anti-Bolshevik Volunteer Army with Alekseev as the political chief. Kornilov promised, "the greater the terror, the greater our victories." He claimed he would be successful even if it was needed "to set fire to half the country and shed the blood of three-quarters of all Russians." (5) Victor Serge claims that in the village of Lezhanka alone, bands of Kornilov's officers killed more than 500 people. (6)

People who were willing to take up arms against the Bolshevik government became known as the White Army. However, they had mixed opinions about what kind of Russia they wanted: "Officers and politicians who remained pro-monarchist attached themselves to each of the White armies because politically there was nowhere else for them to turn. Tension would surface in each of the White armies between those favouring the more democratic progressivism of the February Revolution and those who could not reconcile themselves to it. They made a common if uneasy cause against the Bolsheviks." (7)

General Peter Wrangel, a commander in the north Caucasus, claimed that it was difficult to hold on to areas taken from the Red Army: "In the course of the last few months my command had received considerable reinforcements. In spite of heavy losses, its strength was almost normal. We were well supplied with artillery, technical equipment, telephones, telegraphs, and so on, which we had taken from the enemy. When the Reds had succeeded in making themselves masters of the Kuban district they had recourse to conscription there. Now these forced recruits were deserting en masse, and coming over to us to defend their homes. They were good fighters, but once their own village was cleared of Reds, many of them left the ranks to cultivate their land once more." (8)

Both sides carried out atrocities. One journalist claimed that the Red Army received orders on how to behave by the Bolshevik government: "It was proposed to take hostages from the former officers of the Tsar's army, from the Cadets and from the families of the Moscow and Petrograd middle-classes and to shoot ten for every Communist who fell to the White terror.... The reason given by the Bolshevik leaders for the Red terror was that conspirators could only be convinced that the Soviet Republic was powerful enough to be respected if it was able to punish its enemies, but nothing would convince these enemies except the fear of death, as all were persuaded that the Soviet Republic was falling. Given these circumstances, it is difficult to see what weapon the Communists could have used to get their will respected." (9)

The White Army also carried out acts of terror. Major-General Mikhail Drozdovsky wrote in his diary: "We arrived at Vladimirovka about 5.00 p.m. Having surrounded the village we placed the platoon in position, cut off the ford with machine-guns, fired a couple of volleys in the direction of the village, and everybody there took cover. Then the mounted platoon entered the village, met the Bolshevik committee, and put the members to death. After the executions, the houses of the culprits were burned and the whole male population under forty-five whipped soundly, the whipping being done by the old men. Then the population was ordered to deliver without pay the best cattle, pigs, fowl, forage, and bread for the whole detachment, as well as the best horses." (10)

Walter Duranty, a journalist working for the New York Times interviewed a White Army officer who admitted that they shot all captured members of the Red Army: "They're all Communists, and we can't keep them, you know; they make trouble in the prison camps and start rebellions, and so on. So now we always shoot them. That lot is going back to headquarters for examination - of course they never tell anything, Communists don't, but one or two might be stupid and give away some useful information - then we'll have to shoot them. Of course we don't shoot prisoners, but Communists are different. They always make trouble, so we have no choice." (11)

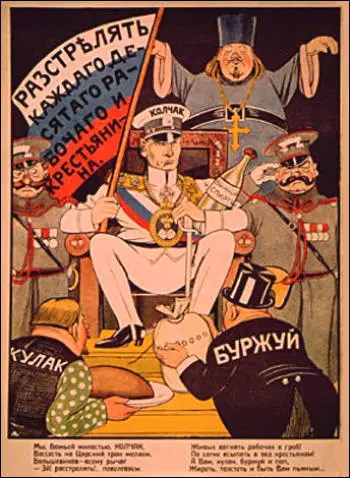

General Alexander Kolchak joined the rebellion and agreed to become a minister in the Provisional All-Russian Government based in Omsk. In November 1918, ministers who were members of the Socialist Revolutionary Party were arrested and Kolchak was named Supreme Ruler with dictatorial powers. In his first speech he claimed: "I will not go down the path of reaction, nor the ruinous path of party politics... my main goal is to create a battle-worthy army, attain a victory over Bolshevism, and establish law and order so that the people may without prejudice choose for themselves the manner of government which they prefer." (12)

General Alfred Knox wrote that Kolchak had "more grit, pluck and honest patriotism than any Russian in Siberia". However, others were not so convinced. "The character and soul of the Admiral are so transparent that one needs no more than one week of contact to know all there is to know about him. He is a big, sick child, a pure idealist, a convinced slave of duty and service to an idea and to Russia.... He is utterly absorbed by the idea of serving Russia, of saving her from Red oppression, and restoring her to full power and to the inviolability of her territory... He passionately despises all lawlessness and arbitrariness, but because he is so uncontrolled and impulsive, he himself often unintentionally transgresses against the law, and this mainly when seeking to uphold the same law, and always under the influence of some outsider." (13)

The Socialist Revolutionaries (SR) now changed sides and joined forces with the Red Army. Kolchak reacted by bring in new laws which established capital punishment for attempting to overthrow the authorities. He also announced that “insults written, printed, and oral, are punishable by imprisonment". Other measures imposed by Kolchak included the suppression of trade unions, disbanding of soviets, and returned factories and land to their previous owners. Kolchak was accused of committing war crimes and one report claimed that he had 25,000 people killed in Ekaterinburg. (14)

The White Army initially had success in the Ukraine where the Bolsheviks were unpopular. The main resistance came from Nestor Makhno, the leader of an Anarchist army in the area. Anarchists chose to work with the Bolsheviks, hoping for a moderation of their policies. Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, led the Red Army and gradually pro-Bolsheviks took control of the Ukraine.

In January 1918 General Lavr Kornilov had around 3,000 men. To crush this force, the Bolsheviks sent an army of 10,000. On 24th February 1918, the Red Army captured Rostov. Kornilov, badly outnumbered, escaped to Ekaterinodar, the capital of the Kuban Soviet Republic. However, in the early morning of 13th April, a Soviet shell landed on his farmhouse headquarters and killed him. He was buried in a nearby village. A few days later, when the Bolsheviks gained control of the village, they unearthed Kornilov's coffin, dragged his corpse to the main square and burnt his remains on the local rubbish dump. (15)

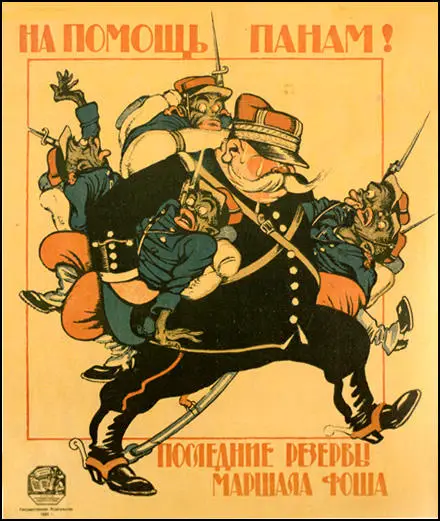

In June 1918 the Allies agreed to send military forces to help the White Army against the Soviet government. The following month French troops were landed in Vladivostok. The French appointed General Maurice Janin head of their military mission and placed him in charge of the Allied forces in western Siberia. "The French themselves contributed 1,076 troops in the summer of 1918. These included an Indo-Chinese battalion, an artillery battery and a reinforced company of volunteers from Alsace-Lorraine." (16)

The British landed 543 men of the 25th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel John Ward. A former member of the Social Democratic Federation, he was initially sympathetic to the Red Army. However, he was appalled by the atrocities committed by the Bolsheviks. With the help of General Alfred Knox, the head of the British Military Mission, helped to supply and train the White Army in Siberia. (17)

Brian Horrocks was a British officer who served under Ward, and was told by him: "I believe we shall rue this business for many years. It is always unwise to intervene in the domestic affairs of any country. In my opinion the Reds are bound to win and our present policy will cause bitterness between us for a long time to come." Horrocks agreed: "How right he was: there are many people today who trace the present international impasse back to that fatal year of 1919. This was well above my head: the whole project sounded most exciting and that was all I cared about." (18)

Among the major Allied powers the Japanese were in the best position to intervene in Siberia. Japan had significant commercial and strategic interests in the Russian Far East, and although they had begun arriving in large numbers on the Western Front, they were relatively fresh to the horrors of trench warfare and had troops to spare. The Japanese arrived on 3rd August and began operating against the Bolsheviks in the Amur and Assuri regions. By November their numbers reached 72,400. (19)

General William S. Graves was given command of the 8th Infantry Division and sent to Siberia under direct orders from President Woodrow Wilson. His orders were to remain strictly apolitical amidst a politically turbulent situation. His main objective was to make sure the Trans-Siberian railroad stayed operational. His troops did not intervene in the the Civil War despite strong pressure brought on him to help the White Army by Admiral Alexander Kolchak. (20)

Morgan Philips Price, a journalist working for the Manchester Guardian, believed that foreign aid helped the Bolsheviks: "The Whites felt that they were saving Russia from the tyranny of a minority and were intending, if victorious, to restore the social order they had always known, tempered with what they vaguely called 'Western Democracy'. The Reds knew they were a minority facing another minority with a majority of waverers and undecided neutrals who would be influenced by the fortunes of the struggle. They felt that they stood for a nobler, higher order of society than that which they had overthrown. It was, therefore, a question which of these two minorities had the strongest moral conviction, which of them had the most courage and belief in themselves. The impression that I now have looking back on these days is that the Bolsheviks won through partly at least because the Whites had prejudiced their cause by calling in the aid of the foreigner." (21)

Lenin appointed Leon Trotsky as commissar of war and was sent to rally the Red Army in the Volga. Soon after taking command he issued the following order: “I give warning that if any unit retreats without orders, the first to be shot down will be the commissary of the unit, and next the commander. Brave and gallant soldiers will be appointed in their places. Cowards, bastards and traitors will not escape the bullet. This I solemnly promise in the presence of the entire Red Army.” (22)

Trotsky proved to be an outstanding military commander and Kazan and Simbirsk were recaptured in September, 1918. The following month he took Samara but the White Army did make progress in the south when General Anton Denikin took control of the Kuban region and General Peter Wrangel began to advance up the Volga. By October, 1918, General Denikin's army had swelled to 100,000 and occupied a front of two hundred miles. (23)

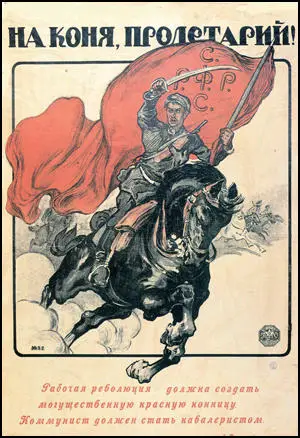

Trotsky announced his strategy on how to defeat the White Army. "Recognizing the existence of an acute military danger, we must take steps really to transform Soviet Russia into a military camp. With the help of the party and the trade-unions a registration must be carried out listing every member of the party, of the Soviet institutions and the trade-unions, with a view to using them for military service." (24)

The main threat to the Bolshevik government came from General Nikolai Yudenich. On 14th October, 1918, he captured Gatchina, only 50 kilometres from Petrograd. It is estimated that there were 200,000 foreign soldiers supporting the anti-Bolshevik forces. Trotsky arrived to direct the defence of the capital. He was not very impressed and it is claimed that his first action was to order Ivan Pavlunovsky, chief of the special section of the Petrograd Cheka, "Comrade Pavlunovsky, I command you to arrest immediately and shoot the entire staff for the defence of Petrograd." (25)

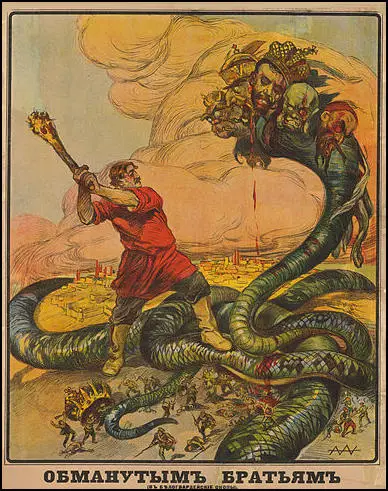

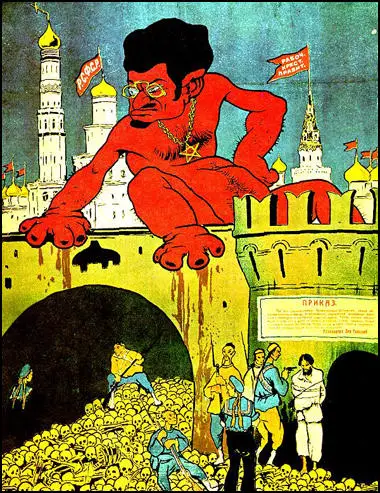

with the dogs, Anton Denikin, Alexander Kolchak and Nikolai Yudenich on leash (1918)

Trotsky made it clear to the people of Petrograd that the city would not be surrendered: "As soon as the masses began to feel that Petrograd was not to be surrendered, and if necessary would be defended from within, in the streets and squares, the spirit changed at once. The more courageous and self-sacrificing lifted up their heads. Detachments of men and women, with trenching-tools on their shoulders, filed out of the mills and factories.... The whole city was divided into sections, controlled by staffs of workers. The more important points were surrounded by barbed wire. A number of positions were chosen for artillery, with a firing range marked off in advance. About sixty guns were placed behind cover on the open squares and at the more important street-crossings. Canals, gardens; walls, fences and houses were fortified. Trenches were dug in the suburbs and along the Neva. The whole southern part of the city was transformed into a fortress. Barricades were raised on many of the streets and squares." (26)

General Vemrenko's army failed in their efforts to cut the vital railway from Tosno to Moscow allowing the Red Army to freely reinforce Petrograd. The 15th Red Army struck from Pskov to Luga, threatening the White right flank and centre. The 7th Red Army now reorganised and reinforced by thousands of Red Guards raised from inside the city pressed westward against the White left and centre. Their combined strength, at least 73,000, forced the Whites back to their original starting point at Narva. (27)

In March, 1919, Admiral Alexander Kolchak captured Ufa and was posing a threat to Kazan and Samara. However, his acts of repression had resulted in the formation of Western Siberian Peasants' Red Army. The Red Army, led by Mikhail Frunze, also made advances and entered Omsk in November, 1919. Kolchak fled eastwards and was promised safe passage by the Czechoslovaks to the British military mission in Irkutsk. However, he was handed over to the Socialist Revolutionaries. He appeared before a five man commission between 21st January and 6th February. At the end of the hearing he was sentenced to death and executed. (28)

Another outstanding Red military commander was Nestor Makhno, an anarchist from the Ukraine. According to Victor Serge: "Nestor Makhno, boozing, swashbuckling, disorderly and idealistic, proved himself to be a born strategist of unsurpassed ability. The number of soldiers under his command ran at times into several tens of thousands. His arms he took from the enemy. Sometimes his insurgents marched into battle with one rifle for every two or three men: a rifle which, if any soldier fell, would pass at once from his still-dying hands into those of his alive and waiting neighbour." (29)

Nesto Makhno always had a large black flag, the symbol of anarchy, at the head of his army, embroidered with the slogans "Liberty or Death" and "the Land to the Peasants, the Factories to the Workers". Makhno later told Emma Goldman that his objective was to establish a libertarian society in the south that would serve as a model for the whole of Russia. When he set-up his first commune near Pokrovskoye, he named it in honour of Rosa Luxemburg.

General Peter Wrangel did not tolerate lawlessness or looting by his troops. (30) However, he complained that this was not always the case. "The war is becoming to some a means of growing rich; re-equipment has degenerated into pillage and peculation. Each unit strives to secure as much as possible for itself, and seizes everything that comes to hand. What cannot be used on the spot is sent back to the interior and sold at a profit.... A considerable number of troops have retreated to the interior, and many officers are away on prolonged missions, busy selling and exchanging loot. The Army is absolutely demoralized, and is fast becoming a collection of tradesmen and profiteers. All those employed on re-equipment work - that is to say, nearly all the officers - have enormous sums of money in their possession; as a result, there has been an outbreak of debauchery, gambling and wild orgies." (31)

The Red Army continued to grow and now had over 500,000 soldiers in its ranks. This included over 40,000 officers who had served under Nicholas II. This was an unpopular decision with many Bolsheviks who feared that given the opportunity, they would betray their own troops. Trotsky tried to overcome this problem by imposing a strict system of punishment for those who were judged to be disloyal. "The Red army had in its service thousands, and, later on, tens of thousands of old officers. In their own words many of them only two years before had thought of moderate liberals as extreme revolutionaries." (32)

In February 1920, General Peter Wrangel was dismissed for conspiring against General Anton Denikin. However, two months later, he was recalled and was given command of the White Army in the Crimea. During this period he recognized and established relations with the new anti-Bolshevik independent republics of Ukraine and Georgia and established a coalition government which attempted to institute progressive land reforms. (33)

On 12th October, 1920, the Bolsheviks signed a peace agreement with Poland. On hearing the news General Peter Wrangel issued the following order: "The Polish Army which has been fighting side by side with us against the common enemy of liberty and order has just laid down its arms and signed a preliminary peace with the oppressors and traitors who designate themselves the Soviet Government of Russia. We are now alone in the struggle which will decide the fate not only of our country but of the whole of humanity. Let us strive to free our native land from the yoke of these Red scum who recognize neither God nor country, who bring confusion and shame in their wake. By delivering Russia over to pillage and ruin, these infidels hope to start a world-wide conflagration." (34)

executed by members of the White Army.

Leon Trotsky was now able to transfer the majority of their combat troops against the southern Whites. Nestor Makhno contributed a brigade from his insurgent army, the majority mounted on horses. In all, there were 188,000 infantry, cavalry and engineers with 3,000 machine-guns, 600 artillery pieces and 23 armoured trains. General Wrangel's army consisted of 23,000 infantry and 12,000 cavalry. (35)

Wrangel was able to hold out for six months but defeat was inevitable. On 11th November, 1920, he ordered his troops to disengage and fall back to the assigned ports for evacuation from the Crimean ports at Eupatoria, Sevastopol, Yalta, Theodosia and Kerch. It is believed that 126 ships had been commandeered to take 145,693 members of the White Army into exile.

David Bullock, the author of The Russian Civil War (2008) has argued that no one has been able to calculate accurately the cost in human life attributable to the Civil War. "Reasoned estimates have placed the number of dead from battle and disease in the Red Army as low as 425,000 and as high as 1,213,000. Numbers for their opponents range from 325,000 to 1,287,000." Another 200,000-400,000 died in prison or were executed as a result of the "Red Terror". A further 50,000 may have been victims of the corresponding "White Terror". Another 5 million are believed to have died in the ensuing famines of 1921-1922, directly caused by the economic disruption of the war. Bullock concludes that in total between 7 and 14 million died as a result of the Russian Civil War. (36)

Primary Sources

(1) David Shub had been a member of the Social Democratic Party in Russia. He wrote about the Russian Civil War while living in exile in the USA.

In the Don Region, Generals Alexeyev and Kornilov, former commanders in chief of the Russian Army, organized a White Army. In January 1918 their forces numbered 3,000 men. To crush this force, the Bolsheviks sent an army of 10,000. Since the peasant population of the region was not in sympathy with the programme of the generals, their troops were forced to retreat to the steppes. General Kornilov himself was killed in action.

Two months later the remnants of the volunteer army, numbering only about one thousand men, organized a new offensive and this time found recruits among the Cossacks. In June their number increased to 12,000; in July to 30,000. By October 1918 this Army swelled to 100,00 and occupied a front of two hundred miles, under the command of General Denikin.

(2) In his book Six Weeks in Russia (1919), Arthur Ransome argued strongly against an Allied invasion of Russia.

Unwin published Six Weeks in Russia in 1919 and sold enormous quantities of it at the lowest possible price. No one could read the plain statements of fact without feeling that the Russian war could not be justified, if only because the people in the book, from Lenin downwards, were quite obviously human beings and not the fantastic bogies that the Interventionists pretended. The little book makes no claim to knowledge of politics or economics, but it does give a clear picture of what Moscow was like in those days of starvation, high hope and unwanted war.

(3) In November, 1918, General Peter Wrangel was fighting with General Anton Denikin in the Kuban area.

In the course of the last few months my command had received considerable reinforcements. In spite of heavy losses, its strength was almost normal. We were well supplied with artillery, technical equipment, telephones, telegraphs, and so on, which we had taken from the enemy. When the Reds had succeeded in making themselves masters of the Kuban district they had recourse to conscription there. Now these forced recruits were deserting en masse, and coming over to us to defend their homes. They were good fighters, but once their own village was cleared of Reds, many of them left the ranks to cultivate their land once more.

(4) Leaflet issued by the Bolsheviks in Mourmansk in 1919.

For the first time in history the working people have got control of their country. The workers of all countries are striving to achieve this object. We in Russia have succeeded. We have thrown off the rule of the Tsar, of landlords, and of capitalists. But we have still tremendous difficulties to overcome. We cannot build a new society in a day. We deserve to be left alone. We ask you, are you going to crash us? To help give Russia back to the landlords, the capitalists and Tsar?

(5) Leon Trotsky, My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (1971)

Treason had nests among the staff and the commanding officers; in fact, everywhere. The enemy knew where to strike and almost always did so with certainty. It was discouraging. Soon after my arrival, I visited the front-line batteries. The disposition of the artillery was being explained to me by an experienced officer, a man with a face roughened by wind and with impenetrable eyes. He asked for permission to leave me for a moment, to give some orders over the field-telephone. A few minutes later two shells dropped, fork-wise, fifty steps away from where we were standing; a third dropped quite close to us. I had barely time to lie down, and was covered with earth. The officer stood motionless some distance away, his face showing pale through his tan. Strangely enough, I suspected nothing at the moment; I thought it was simply an accident. Two years later I suddenly remembered the whole affair, and, as I recalled it in its smallest detail, it dawned on me that the officer was an enemy, and that through some intermediate point he had communicated with the enemy battery by telephone, and had told them where to fire. He ran a double risk – of getting killed along with me by a White shell, or of being shot by the Reds. I have no idea what happened to him later.

I had no sooner returned to my carriage than I heard rifle-shots all about me. I rushed to the door. A White airplane was circling above us, obviously trying to hit the train. Three bombs dropped on a wide curve, one after another, but did no damage. From the roofs of our train rifles and machine-guns were shooting at the enemy. The airplane rose out of reach, but the fusillade went on – it seemed as if every one were drunk. With considerable difficulty I managed to stop the shooting. Possibly the same artillery officer had sent word as to the time of my return to the train. But there may have been other sources as well.

The more hopeless the military situation of the revolution, the more active the treason. It was necessary, no matter what the cost, to overcome as quickly as possible the automatic inertia of retreat, in which men no longer believe that they can stop, face about, and strike the enemy in the chest. I brought about fifty young party men from Moscow with me on the train. They simply outdid themselves, stepping into the breach and fairly melting away before my very eyes through the recklessness of their heroism and sheer inexperience. The posts next to theirs were held by the fourth Latvian regiment. Of all the regiments of the Latvian division that had been so badly pulled to pieces, this was the worst. The men lay in the mud under the rain and demanded relief, but there was no relief available. The commander of the regiment and the regimental committee sent me a statement to the effect that unless the regiment was relieved at once “consequences dangerous for the revolution” would follow. It was a threat. I summoned the commander of the regiment and the chairman of the committee to my car. They sullenly held to their statement. I declared them under arrest. The communications officer of the train, who is now the commander of the Kremlin, disarmed them in my compartment. There were only two of us on the train staff; the rest were fighting at the front. If the men arrested had showed any resistance, or if their regiment had decided to defend them and had left the front line, the situation might have been desperate. We should have had to surrender Sviyazhsk and the bridge across the Volga. The capture of my train by the enemy would undoubtedly have had its effect on the army. The road to Moscow would have been left open. But the arrest came off safely. In an order to the army, I announced the commitment of the commander of the regiment to trial before the revolutionary tribunal. The regiment remained at its post. The commander was merely sentenced to prison.

The communists were explaining, exhorting, and offering example, but agitation alone could not radically change the attitude of the troops, and the situation did not allow sufficient time for that. We had to decide on sterner measures. I issued an order which was printed on the press in my train and distributed throughout the army: “I give warning that if any unit retreats without orders, the first to be shot down will be the commissary of the unit, and next the commander. Brave and gallant soldiers will be appointed in their places. Cowards, bastards and traitors will not escape the bullet. This I solemnly promise in the presence of the entire Red Army.”

Of course the change did not come all at once. Individual detachments continued to retreat without cause, or else would break under the first strong onset. Sviyazhsk was open to attack. On the Volga, a steamboat was held ready for the staff. Ten men of my train crew, mounted on bicycles, were on guard over the pathway between the staff headquarters and the steamship landing. The military Soviet of the Fifth army proposed that I move to the river. It was a wise suggestion, but I was afraid of the bad effect on an army already nervous and lacking in assurance. Just at that time, the situation at the front suddenly grew worse. The fresh regiment on which we had been banking left its post, with its commissary and commander at its head, and seized the steamer by threat of arms, intending to steam to Nijni-Novgorod.

(6) Leon Trotsky, My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (1971)

Everyone expected an early surrender of the city to the Whites, and so people were afraid of becoming too conspicuous. But as soon as the masses began to feel that Petrograd was not to be surrendered, and if necessary would be defended from within, in the streets and squares, the spirit changed at once. The more courageous and self-sacrificing lifted up their heads. Detachments of men and women, with trenching-tools on their shoulders, filed out of the mills and factories. The workers of Petrograd looked badly then; their faces were grey from undernourishment; their clothes were in tatters; their shoes, sometimes not even mates, were gaping with holes.

"We will not give up Petrograd, comrades!"

"No." The eyes of the women burned with especial fervour. Mothers, wives, daughters, were loath-to abandon their dingy but warm nests. "No, we won't give it up," the high-pitched voices of the women cried in answer, and they grasped their spades like rifles. Not a few of them actually armed themselves with rifles or took their places at the machine-guns. The whole city was divided into sections, controlled by staffs of workers. The more important points were surrounded by barbed wire. A number of positions were chosen for artillery, with a firingrange marked off in advance. About sixty guns were placed behind cover on the open squares and at the more important street-crossings. Canals, gardens; walls, fences and houses were fortified. Trenches were dug in the suburbs and along the Neva. The whole southern part of the city was transformed into a fortress. Barricades were raised on many of the streets and squares. A new spirit was breathing from the workers' districts to the barracks, the rear units, and even to the army in the field.

Yudenich was only from ten to fifteen versts away from Petrograd, on the same Pulkovo heights where I had gone two years before, when the revolution which had just assumed power was fighting for its life against the troops of Kerensky and Krasnov. Once more the fate of Petrograd was hanging by a thread, and we had to break the inertia of retreat, instantly and at any cost.

(7) Letter by General Peter Wrangel that was sent to General Anton Denikin on 9th December, 1919.

The continual advance has reduced the Army's effective force. The rear has become too vast. Disorganization is all the greater because of the re-equipment system which Supreme Headquarters have adopted; they have turned over this duty to the troops and take no share in it themselves.

The war is becoming to some a means of growing rich; re-equipment has degenerated into pillage and peculation. Each unit strives to secure as much as possible for itself, and seizes everything that comes to hand. What cannot be used on the spot is sent back to the interior and sold at a profit. The rolling-stock belonging to the troops has taken on enormous dimensions - some regiments have two hundred carriages in their wake. A considerable number of troops have retreated to the interior, and many officers are away on prolonged missions, busy selling and exchanging loot.

The Army is absolutely demoralized, and is fast becoming a collection of tradesmen and profiteers. All those employed on re-equipment work - that is to say, nearly all the officers - have enormous sums of money in their possession; as a result, there has been an outbreak of debauchery, gambling and wild orgies.

(8) Morgan Philips Price, My Three Revolutions (1969)

The Red Terror now began. I shall never forget one of the Isvestia articles for Saturday, September 7th. There was no mistaking its meaning. It was proposed to take hostages from the former officers of the Tsar's army, from the Cadets and from the families of the Moscow and Petrograd middle-classes and to shoot ten for every Communist who fell to the White terror. Shortly after a decree was issued by the Central Soviet Executive ordering all officers of the old army within territories of the Republic to report on a certain day at certain places. A panic resulted among the Moscow middle-classes, as I could see from conversations which I overheard at the Tolstoy's house. Some of the visitors counselled submission to the decree, while others swore resistance to the last. The reason given by the Bolshevik leaders for the Red terror was that conspirators could only be convinced that the Soviet Republic was powerful enough to be respected if it was able to punish its enemies, but nothing would convince these enemies except the fear of death, as all were persuaded that the Soviet Republic was falling. Given these circumstances, it is difficult to see what weapon the Communists could have used to get their will respected.

All civilized restraints had gone on both sides and this was civil war of the worst kind to the bitter end. Both the Reds and Whites were in the throes of a struggle in which physical force was the only deciding factor. The Whites felt that they were saving Russia from the tyranny of a minority and were intending, if victorious, to restore the social order they had always known, tempered with what they vaguely called 'Western Democracy'. The Reds knew they were a minority facing another minority with a majority of waverers and undecided neutrals who would be influenced by the fortunes of the struggle. They felt that they stood for a nobler, higher order of society than that which they had overthrown. It was, therefore, a question which of these two minorities had the strongest moral conviction, which of them had the most courage and belief in themselves. The impression that I now have looking back on these days is that the Bolsheviks won through partly at least because the Whites had prejudiced their cause by calling in the aid of the foreigner.

Needless to say, the terror produced deplorable excesses on both sides. I was horrified and even dared to protest about it to people I was in contact with in the Foreign Office. Of the officers in the Tsarist army who reported in Petrograd, five hundred were seized and executed without trial. A large number of them were innocent men who were simply sacrificed to strike terror into the heart of the Whites. Similar horrors and murders of Reds took place in the territory occupied by Krasnov's Cossacks. It is useless to dwell upon all this which is now history, but it is necessary to record and emphasize the fact that foreign assistance to the Russian Whites was the principal cause of the intense bitterness of the struggle which made excesses on a large scale on both sides inevitable. Now for the first time since the Bolsheviks seized power was blood really running in Russia. I can testify from my experiences till then that there had been little loss of life but now the casualties in the civil war began on a big scale.

(9) After the Civil War, the leader of the Red Army, Leon Trotsky wrote about the threats that the White Army had posed to the Soviet government in 1919.

In June 1919 an important fort called 'Krasnaya Gorka' in the Gulf of Finland, was captured by a detachment of Whites. A few days later it was recaptured by a force of Red marines. Then it was discovered that the chef of the staff of the Seventh army, Colonel Lundkvist, was transmitting all information to the Whites. There were other conspirators working hand-in-glove with him. This shook the army to its very core.

In July General Yudenich was made Commander-in-Chief of the North-Western army of the Whites, and was recognized by Kolchak as his representative. In August, with the aid of England and Estonia, the Russian 'north-western government' was established. The English navy in the Gulf of Finland promised Yudenich its support. Yudenich's offensive was timed for a moment when we were desperately pressed on the other fronts. Denikin had occupied Orel and was threatening Tula, the munitions-manufacturing centre.

(10) Major-General Mikhail Drozdovsky, diary entry (22nd March, 1918)

We arrived at Vladimirovka about 5.00 p.m. Having surrounded the village we placed the platoon in position, cut off the ford with machine-guns, fired a couple of volleys in the direction of the village, and everybody there took cover. Then the mounted platoon entered the village, met the Bolshevik committee, and put the members to death. After the executions, the houses of the culprits were burned and the whole male population under forty-five whipped soundly, the whipping being done by the old men. Then the population was ordered to deliver without pay the best cattle, pigs, fowl, forage, and bread for the whole detachment, as well as the best horses.

(11) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951)

On 7th October Yudenich captured Gatchina, about twenty-five miles from Petrograd. Two days later his advance forces entered Ligovo, on the city's outskirts, about nine miles away.

There were no trains and no fuel for evacuation, and scarcely a few dozen cars. We had sent the children of known militants off to the Urals; they were travelling there now in the first snows, from one famished village to the next, not knowing where to halt.

We arranged new identities for ourselves, trying to "change our faces". It was relatively easy for those with beards, who only had to shave, but as for the others.

I no longer slept at the Astoria, whose ground floor was lined with sandbags and machine-guns against a siege; I spent my nights with the Communist troops in the outer defences.

(12) A biography of Mikhail Frunze was included in the The Granat Encyclopaedia of the Russian Revolution (1924).

After the Yaroslav rebellion, Frunze was appointed Commissar for the Yaroslav Military District. From there he was transferred to the Urals Front and under his command the Southern Army Group of the Eastern Front inflicted a decisive defeat on Kolchak's troops. Following this, he was put in charge of the whole Eastern Front and directed the operations to sweep the Whites out of Turkestan.

During the revolution in Bukhara in August which overthrew the Emir's forces out of the Bukharan Republic with detachments of the Red Army. In September 1920 he ordered an offensive against Wrangel on the Southern Front. After the seizure of the Crimea and the elimination of Wrangel's forces, he became commander of all troops in the Crimea and the Ukraine, and the representative of the Revolutionary Military Council there. Under his leadership the Petlyura and Makhno rebellions were crushed.

(13) Brian Horrocks, a British soldier, wrote about his experiences frighting with the White Army in his autobiography, A Full Life (1960)

During my time in Germany I had lived for many months with one other British officer in a room with fifty Russian officers. So I had perforce to learn Russian. When, therefore, the War Office called for volunteers who knew the language to go to Russia to help the White armies in their struggle against the Bolsheviks, I immediately applied and was ordered to Siberia. Instead of returning to my regiment for some elementary instruction in military matters and for some much-needed discipline, I set off on what promised to be a far more exciting venture.

The Red armies after seizing power in Moscow and Petrograd had overrun most of Siberia. During the winter of 1918-19 the Whites, under command of Admiral Koltchak, had driven them back into Russia proper. Apparently this success had been achieved mainly by the Czechs. After the revolution thousands of Czechs had come to Siberia and, realizing that their only chance of survival lay in a cohesive effort, they had formed themselves into a corps under command of a Czech general called Gaida. With the exception of a few battalions formed from Russian officer cadet training units, plus one division of Poles, these Czechs were the only reliable troops at Koltchak's disposal. Now, very naturally, they wanted to go home, and it was our task to train and equip White Russian forces raised in Siberia to take their place on the front.

We were warned that the White Russian officers and intelligentsia resented both our help and our presence in their country. One wise old British colonel said even in those early days, "I believe we shall rue this business for many years. It is always unwise to intervene in the domestic affairs of any country. In my opinion the Reds are bound to win and our present policy will cause bitterness between us for a long time to come."

How right he was: there are many people today who trace the present international impasse back to that fatal year of 1919. This was well above my head: the whole project sounded most exciting and that was all I cared about.

(14) General Peter Wrangel, statement issued to the White Army (19th October, 1920)

The Polish Army which has been fighting side by side with us against the common enemy of liberty and order has just laid down its arms and signed a preliminary peace with the oppressors and traitors who designate themselves the Soviet Government of Russia. We are now alone in the struggle which will decide the fate not only of our country but of the whole of humanity. Let us strive to free our native land from the yoke of these Red scum who recognize neither God nor country, who bring confusion and shame in their wake. By delivering Russia over to pillage and ruin, these infidels hope to start a world-wide conflagration.

(15) General Peter Wrangel, statement issued to the people of Russia (29th October, 1920)

People of Russia! Alone in its struggle against the oppressor, the Russian Army has been maintaining an unequal contest in its defence of the last strip of Russian territory on which law and truth hold sway. Conscious of my responsibility, I have tried to anticipate every possible contingency from the very beginning.

I now order the evacuation and embarkation at the Crimean ports of all those who are following the Russian Army.

I have done everything that human strength can do to fulfill my duty to the Army and the population. We cannot foretell our future fate. We have no other territory than the Crimea. We have no money. Frankly as always, I warn you all of what awaits you. May God grant us strength and wisdom to endure this period of Russian misery, and to survive it.

(16) Albert Rhys Williams, Through the Russian Revolution (1923)

For four years the Communists have had control of Russia. What are the fruits of their stewardship? "Repression, tyranny, violence," cry the enemies. "They have abolished free speech, free press, free assembly. They have imposed drastic military conscription and compulsory labour. They have been incompetent in government, inefficient in industry. They have subordinated the Soviets to the Communist Party. They have lowered their Communist ideals, changed and shifted their program and compromised with the capitalists."

Some of these charges are exaggerated. Many can be explained away. Friends of the Soviet grieve over them. Their enemies have summoned the world to shudder and protest against them.

When I am tempted to join the wailers and the mud-slingers my mind goes back to the tremendous obstacles it confronted. In the first place the Soviet faced the same conditions that had overwhelmed the Tsar and Kerensky governments, i.e., the dislocation of industry, the paralysis of transport, the hunger and misery of the masses.

In the second place the Soviet had to cope with a hundred new obstacles - desertion of the intelligentsia, strike of the old officials, sabotage of the technicians, excommunication by the church, the blockade by the Allies. It was cut off from the grain fields of the Ukraine, the oil fields of Baku, the coal mines of the Don, the cotton of Turkestan - fuel and food reserves were gone.

(17) Walter Duranty, I Write As I Please (1935)

During the first week I reported the "War" from Riga, despite the all-embracing pass I had received from the Lettish Commander-in-Chief. For two good reasons, first, that it would have taken two or three days to reach the Front, had a train been available, which was doubtful, as all the locomotives save one were being used behind the lines of advance. Second, that through the courtesy of the Lettish General Staff and my British friends, I was getting full information two or three hours before the short Lettish communiques were issued, and was thus able to write a good running story every day. For some curious reason there were practically no other newspaper men in Riga at that time. They naturally supposed that the peace negotiations between the Soviet, Estonia and Finland, which had now been resumed in Dorpat, were the central interest in the Baltic. None of them foresaw, any more than I did, the sudden resumption of hostilities by the Letts. As far as I remember none of them had come to Riga by the time I did leave for the northern front, on a troop train in company with the American flying officer, Major Curtis, whom I mentioned before when telling how the Lett sentry had shot at us in the street. We were to have a much narrower escape on this journey, though of a different character. The troop train made such good time, since the engine was not allowed to be removed en route for shunting, that we arrived at midnight instead of 8 a.m. at the wayside station from which we were to drive to headquarters. The station Commandant had prepared food and a room for us, but I have rarely spent a less pleasant night. The place was alive with vermin, amongst which the grey typhus louse was all too prominent. Typhus was epidemic throughout the region and at that very time the unfortunate remnant of Yudenich's army was dying like flies in Narva. Curtis and I had smeared ourselves liberally with oil of anise, the specific used by the German army on the Eastern Front, whose smell is supposed to deter the hungry cootie. Everything we ate or drank reeked of it, but I doubt whether it was much protection, as we were plentifully bitten, with no worse results, however, than a day or two's discomfort. But the thought that each fresh bite might be injecting deadly germs was not comforting for a long and sleepless night.

We received a warm welcome at headquarters, and I had an excellent interview with the Commanding Officer, who not only explained in detail what had happened and the subsequent objectives, but offered us his private sleigh, and an aide-de-camp to act as interpreter, to take us up to the Front, which was now about fifty kilometers eastwards along the main railway line running south from the Russian town of Pakof to Dvinsk. The General said that the Letts had that morning captured the important junction of Marienhausen, and that we should probably find Divisional Headquarters somewhere in that neighbourhood. I sent my story by military courier, who was returning to Riga the next morning, and at 7 a.m. we set out in pitch darkness in a big two-horse sleigh. We drove all day without seeing a soul, along a narrow trail not more than five yards wide through dense pine forest. The Lettish advance had been so rapid, our interpreter said, that the woods were still full of Red stragglers, and until they were rounded up the civil population would lie low at home. We were to find out later how true this was.

About three o'clock we met a train of peasant sleighs and moved out of the track to let them pass. It was a convoy of prisoners, eight or ten of them wounded, lying on the sleighs the rest, about twenty, marching on foot, under the guard of four Lettish soldiers and a Sergeant with rifles. On the last sleigh, the Sergeant told us, was a 'Bolshevik Commissar', who had only a slight flesh wound in the arm but who had the privilege of riding because of his superior rank. I gathered later that although he wore uniform, he must have been one of the trusted civilian Communists then attached to military units of the Red Army to keep an eye on the officers, many of whom were ex-Whites of doubtful loyalty. Owing to the shortage of officer material of their own, the Reds commonly used `White' officers in this way during the Civil War, but found it necessary to supplement them by civilian 'guardians' called Commissars. We offered the man some brandy and began to talk to him. He spat back at us like an infuriated cat. "Tell him there is no need to be so rude about it," I said to the young aide-de-camp. "We wish him no harm and it won't hurt him to be polite.' Again the Commissar replied with a burst of Russian expletive. `He says you can go to hell," said the interpreter. "He knows he is going to be shot, so why should he satisfy your curiosity? He says to hell with America too, and all the other stinking rotten capitalists." Meanwhile the rest of the prisoners watched with mildly curious faces.

As we continued our journey, I said to the aide-de-camp, "What's that the Commissar said about being shot? What did he mean?"

"Oh, yes," he replied cheerfully, "they'll all be shot, that lot. They're all Communists, and we can't keep them, you know; they make trouble in the prison camps and start rebellions, and so on. So now we always shoot them. That lot is going back to headquarters for examination - of course they never tell anything, Communists don't, but one or two might be stupid and give away some useful information - then we'll have to shoot them. Of course we don't shoot prisoners," he added hastily, "but Communists are different. They always make trouble, so we have no choice." "But do they know that?" I persisted. "I mean not only the Commissar, but the others?" "I expect so, they all heard what he said, didn't they?"

Now that was a curious example of Russian temperament. These men were such devoted Communists that they would not speak to save their lives and would not rest quiet in prison camps. Yet here were twenty of them unwounded on a narrow trail through trackless woods, and only four guards, or five with the Sergeant, armed with rifles. If the prisoners had broken away in a body, it is doubtful whether the guards would have had time to shoot any of them. Mind you, they were not chained or bound in anyway. There were Red soldiers a-plenty in the forest, and a group of determined men could undoubtedly have found their way back through the loose Lettish lines to the Red outposts. But no, they trudged on apathetically to their fate. To Curtis and me it was incomprehensible.

Two days later at the Lettish Division Headquarters near Marienhausen I had a further example of Russian indifference to death. Three Communists were to be executed; they were so tough and recalcitrant that it wasn't any good sending them back to Army Headquarters. I saw them stroll out towards a fence about a quarter of a mile from where I was standing. They were accompanied by a Lettish Sergeant with a big cavalry revolver. I watched through my glasses, without the least compunction or pity because at that time I regarded the Bolsheviks as enemies of God and man, and the Sergeant later told me what happened. The Russians, it seemed, had one cigarette between them. When they lined up with their backs to the fence the first man said, "Do you mind if I smoke three puffs of the cigarette?" I may add that they were not bound or blindfolded. The Sergeant nodded assent, whereupon the man lit his cigarette, cursing the while because two or three of his matches failed to light, drew three or four puffs of smoke, then, passing it on to his comrade on the right, slightly bent his head to receive the Lett's bullet. The same performance was repeated with the second Communist, whereupon the third said, "You may as well let me finish the cigarette." Again the Sergeant nodded, then this man also took a bullet in the brain and died.

At the moment the most interesting thing to me was the fact that all of them received a bullet of the same calibre under the left ear, but all died different ways. The first man fell flat on his back as if he had been hit with a club, kicked his heels for a minute, then lay still. The second stood swaying a moment, then fell forward on his face and flopped his hands twice in the snow. The third staggered a step backwards as the bullet hit him, then a step forward, putting out his hands as if to save himself from falling, then slumped down in a heap without a movement of hand or foot. They were all men of about the same physique and I couldn't understand this difference until it was explained to me by an American nerve specialist who visited Moscow in 1933 or 1934, "It is a matter of muscular tension," he said. "The first man was limp when the bullet hit him, so it knocked him backwards. The second and third were braced as if to jump forward, but the muscular bracing of the second was greater than that of the third." Which sounds reasonable when you come to think of it.

But what puzzled Curtis and me was that one of the three, or all of them together, did not take a swing at the Lettish Sergeant and run for it. The edge of the forest was only a hundred yards away and they would have had at least an even chance of getting clear instead of smoking a cigarette and dying like sheep.

(18) In 1924 Alice Hamilton spent a month in the Soviet Union. She wrote a letter to her family about her views on the new communist government (10th November, 1924)

Russia is such a strange mixture. I can't generalize about it, because one thing contradicts another. On the one hand there is the cruelty, even now, to the counter-revolutionaries, but then it is not fair to dwell on that because both sides were cruel, the Bolsheviks more so only because they came out on top. Everyone here assumes that if the Whites had won they would have exterminated the Reds so far as they could catch them. And I have been told by Whites that in the matter of brutality, of killing prisoners, and hostages, of torturing and the rest, there was nothing to choose between the two, only that one woman who was a Red Cross nurse under both sides, said that she blamed the Whites more, because they were the highest in the land and one expected more of them than of the lowest.

Student Activities

Russian Revolution Simmulation

Bloody Sunday (Answer Commentary)

1905 Russian Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Russia and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

The Life and Death of Rasputin (Answer Commentary)

The Abdication of Tsar Nicholas II (Answer Commentary)

The Provisional Government (Answer Commentary)

The Kornilov Revolt (Answer Commentary)

The Bolsheviks (Answer Commentary)

The Bolshevik Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject