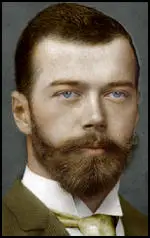

Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas, the eldest son of Alexander III, the Tsar of Russia, and Marie Feodorovna (formerly Princess Dagmar of Denmark), was born at Krasnoye Selo in May 1868. He had five younger siblings: Alexander (1869–1870), George (1871–1899), Xenia (1875–1960), Michael (1878–1918) and Olga (1882–1960).

The Romanov family had ruled Russia since 1613 when the leading nobles decided to place the sixteen-year-old Michael Romanov, a distant relative of Ivan the Terrible, on the throne. He took the title "Emperor and Autocrat of all Russia". The Emperor of Russia became known as the Tsar (Czar) and imposed autocratic rule - government by one man. All the other contenders were murdered. Unlike in other European countries, the Tsars of Russia did not take advice from an elected parliament. The country wa s run by a ten man ministerial council. Each minister was both appointed and dismissed by the Tsar. (1)

Alexander II became the sixteenth Romanov tsar in 1855. He attempted to bring in some political reforms. This included permitting each district to set up a Zemstvo. These were local councils with powers to provide roads, schools and medical services. However, the right to elect members was restricted to the wealthy. He also continued with rigid censorship and to take part in political discussion groups, could be punished by execution. The novelist, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, was found guilty of this offence and was sentenced to death, but it was commuted and he was sent to Siberia instead. (2)

In 1861 Alexander issued his Emancipation Manifesto that proposed 17 legislative acts that would free the serfs in Russia. Alexander announced that personal serfdom would be abolished and all peasants would be able to buy land from their landlords. The State would advance the the money to the landlords and they would recover it from the peasants in 49 annual sums known as redemption payments. (3)

Victor Serge, the author of Year One of the Russian Revolution (1930), pointed out: "With a population of sixty-seven million, Russia had twenty-three million serfs belonging to 103,000 landlords. The arable land which the freed peasantry had to rent or buy was valued at about double its real value (342 million roubles instead of 180 million); yesterday's serfs discovered that, in becoming free, they were now hopelessly in debt." (4)

There were several attempts on the life of the Tsar by the People's Will terrorist group. On 1st March, 1881, Alexander II decided to travel along the Ekaterinsky Canal. An armed Cossack sat with the coach-driver and another six Cossacks followed on horseback. Behind them came a group of police officers in sledges. Perovskaya, who was stationed at the intersection between the two routes, gave the signal to Nikolai Rysakov and Timofei Mikhailov to throw their bombs at the Tsar's carriage. The bombs missed the carriage and instead landed amongst the Cossacks. The Tsar was unhurt but insisted on getting out of the carriage to check the condition of the injured men. (5)

While he was standing with the wounded Cossacks another terrorist, Ignatei Grinevitski, threw his bomb. Alexander was killed instantly and the explosion was so great that Grinevitski also died from the bomb blast. In the confusion Sophia Perovskaya was able to slip away. She told the surviving members of the group: "I think it was a success he was either killed or very badly wounded." Soon afterwards news reached Sophia that the Tsar had died at the scene of the bombing. (6)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook, make a donation to Spartacus Education and subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Alexander III became Tsar of Russia on the assassination of Alexander II. He immediately cancelled his father's plans to introduce a representative assembly and announced he had no intention of limiting his autocratic power. During his reign he followed a repressive policy against those seeking political reform. Alexander also pursued a policy of Russification of national minorities. This included imposing the Russian language and Russian schools on the German, Polish and Finnish peoples living in the Russian Empire.

Lionel Kochan, the author of Russia in Revolution (1970) pointed out: "In this new world of flux, when all manner of alien institutions and alien political and philosophic doctrines threatened Russia's precarious stability the autocracy was more necessary than ever as an agent of the status quo." Konstantin Pobedonostsev, the Ober-Procurator of the Most Holy Synod, the non-clerical official who supervised the Russian Orthodox Church, was Alexander's key adviser: "Pobedonostsev... initiated and justified the enforcement of uniformity of belief and conduct in every sphere of life.... On this basis, Pobedonostsev defended the censor and denounced freedom of the press as an avenue to the dissemination of falsehood." (7)

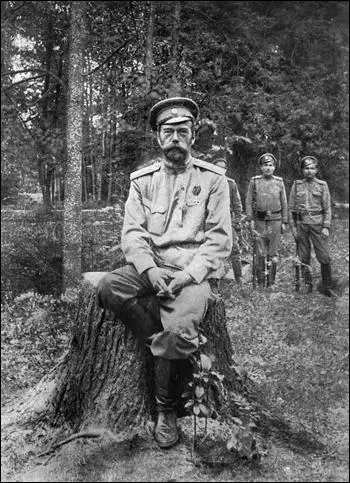

Tsar Nicholas II of Russia

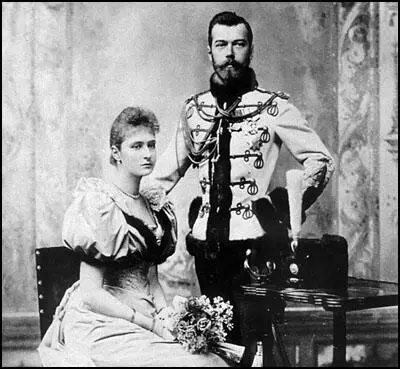

Nicholas fell in love with Alexandra of Hesse-Darmstadt since 1889. Nicholas wrote in his diary: "It is my dream to one day marry Alix H. I have loved her for a long time, but more deeply and strongly since 1889 when she spent six weeks in Petersburg. For a long time, I have resisted my feeling that my dearest dream will come true." However, Alexander III was vehemently anti-German and had no intention of allowing the couple to marry. (8)

Nicholas, as the eldest son, underwent training to become the next Tsar. He therefore became a target for the terrorists. In 1890 Nicholas, along with his younger brother George and their cousin Prince George of Greece set out on a world tour. He visited Egypt, India, Singapore, and Bangkok, but while traveling through the city of Otsu, Japan in April 1891, he was the victim of an assassination attempt. (9)

Nicholas proposed to Alexandra in April 1894, but she rejected him on the grounds of her refusal to convert to the Russian Orthodox faith. However, after pressure from Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany she changed her mind and accepted the offer. Her grandmother, Queen Victoria, also approved of the marriage and lived with her until the wedding could take place. (10) punishment."

Despite several assassination attempts Alexander III died of liver disease on 20th October, 1894. Nicholas inherited an empire that occupied one-sixth of the land surface of the world: "Stretching from Poland in the west of the Pacific Ocean in the east, from the Arctic Circle in the north to the Black Sea in the south, it was an area of considerable diversity in climate and landscape, and in the variety of peoples who attempted to make a living within it. The vast majority of the inhabitants were peasant farmers, living in scattered village communities." (11)

The marriage of Nicholas II and Alexandra took place in the Grand Church of the Winter Palace of St Petersburg on 26th November 1894. Alexandra was a strong believer in the autocratic power of Tsardom and she urged him to resist demands for political reform. According to Barbara W. Tuchman, the author of The Guns of August (1962): "Though it could hardly be said that the Tsar governed Russia in a working sense, he ruled as an autocrat and was in turn ruled by his strong-willed if weak-witted wife. Beautiful, hysterical, and morbidly suspicious, she hated everyone but her immediate family and a series of fanatic or lunatic charlatans who offered comfort to her desperate soul." (12)

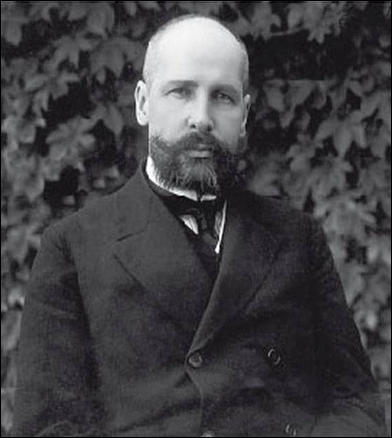

Sergei Witte

Nicholas II inherited Sergei Witte as his Minister of Finance. Witte combined his experience in the railway industry with a strong interest in foreign policy. He encouraged the expansion of the Trans-Siberian Railway and organized the construction of the Chinese Eastern Railway. Witte also devalued Russia's currency to promote international trade, erecting high tariffs to protect Russian industry, and placing Russia on the gold standard giving the country a stable currency for international dealings. (13)

Witte also played an important role in helping to increase the speed of Russia's industrial development. He realised that the skills needed for rapid industrial growth could not be found in Russia. Foreign engineers were encouraged to work there, and Witte relied on foreign investors to supply much of the money to finance industrial growth. "This strategy was highly successful and by 1900 Russia was producing three times as much iron as in 1890, and more than twice as much coal." (14)

However, Witte still believed Russia had not industrialized fast enough: "In spite of the vast successes achieved during the last twenty years (i.e. 1880-1900) in our metallurgical and manufacturing industry, the natural resources of the country are still underdeveloped and the masses of the people remain in enforced idleness... To the present epoch has fallen the difficult task of making up for what has been neglected in an economic slumber lasting two centuries." Witte insisted that unless this growth took place Russia would be "politically impotent to the degree that they were economically dependent on foreign industry." (15)

Nicholas II and Alexandra disliked St. Petersburg. Considering it too modern, they moved the family residence in 1895 from Anichkov Palace to Alexander Palace in Tsarskoe Selo, where they lived in seclusion. In 1902 Nicholas II appointed the reactionary Vyacheslav Plehve as his Minister of the Interior. Plehve's attempts at suppressing those advocating reform was completely unsuccessful. In a speech he made in 1903 Plehve argued: "Western Russia some 90 per cent of the revolutionaries are Jews, and in Russia generally - some 40 per cent. I shall not conceal from you that the revolutionary movement in Russia worries us but you should know that if you do not deter your youth from the revolutionary movement, we shall make your position untenable to such an extent that you will have to leave Russia, to the very last man!" (16)

Plehve also secretly organized Jewish Pogroms. Plehve was hated by all radicals in Russia. Leon Trotsky commented: "Plehve was as powerless against sedition as his successor, but he was a terrible scourge against the kingdom of liberal newspapermen and rural conspirators. He loathed the revolution with the fierce loathing of a police detective grown old in his profession, threatened by a bomb from around every street corner; he pursued sedition with bloodshot eyes - but in vain. Plehve was terrifying and loathsome as far as the liberals were concerned, but against sedition he was no better and no worse than any of the others. Of necessity, the movement of the masses ignored the limits of what was allowed and what was forbidden: that being so, what did it matter if those limits were a little narrower or a little wider?" (17)

Sergei Witte believed in the need for political reforms to go with this economic growth. This resulted in him making powerful enemies, including Plehve, who favoured a policy of repression. Plehve and Witte disagreed on the issue of industrialization."Witte envisioned a Russia in which the autocracy coexisted with industrial capitalism, Plehve a Russia in which the old regime lived on, with the landed nobility holding a place of honor, a regime that had no place for Jews, whom he considered a cancer on the body politic." (18) In August, 1903, Plehve passed on documents to the Tsar that suggested Witte was part of a Jewish conspiracy. As a result Witte was removed as Minister of Finance. (19)

On 28th July, 1904, Plehve was killed by a bomb thrown by Egor Sazonov on 28th July, 1904. Plehve was replaced by Pyotr Sviatopolk-Mirsky, as Minister of the Interior. He held liberal views and hoped to use his power to create a more democratic system of government. Sviatopolk-Mirsky believed that Russia should grant the same rights enjoyed in more advanced countries in Europe. He recommended that the government strive to create a "stable and conservative element" among the workers by improving factory conditions and encouraging workers to buy their own homes. "It is common knowledge that nothing reinforces social order, providing it with stability, strength, and ability to withstand alien influences, better than small private owners, whose interests would suffer adversely from all disruptions of normal working conditions." (20)

Tsar Nicholas II made a speech in January, 1895, denouncing the "senseless dreams" of those who favour democratic reforms. Leon Trotsky later commented: "I was fifteen at the time. I was unreservedly on the side of the nonsensical dreams, and not on that of the Tsar. Vaguely I believed in a gradual development which would bring backward Russia nearer in advanced Europe. Beyond that my political ideas did not go." (21)

Sergi Witte, the Minister of Finance, was one of the few progressives in the government and warned about the problems of ruling Russia in this way. "With many nationalities, many languages and a nation largely illiterate, the marvel is that the country can be held together even in autocracy. Remember one thing: if the tsar's government falls, you will see absolute chaos in Russia, and it will be many a long year before you can see another government able to control the mixture that makes up the Russian nation." (22)

Revolutionary Political Parties

Nicholas II speeches defending the status quo encouraged attempts to form a new revolutionary party. In March, 1898, the various Marxist groups in Russia met in Minsk and decided to form the Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP). Members included Julius Martov, Lenin, Leon Trotsky, Gregory Zinoviev, Anatoli Lunacharsky, Joseph Stalin, Mikhail Lashevich, Nadezhda Krupskaya, Mikhail Frunze, Alexei Rykov, Yakov Sverdlov, Lev Kamenev, Maxim Litvinov, Vladimir Antonov, Felix Dzerzhinsky, Vyacheslav Menzhinsky, Kliment Voroshilov, Vatslav Vorovsky, Yan Berzin, George Plekhanov, Pavel Axelrod, Leon Trotsky, Lev Deich, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, Vera Zasulich, Irakli Tsereteli, Moisei Uritsky, Natalia Sedova, Noi Zhordania, Fedor Dan and Gregory Ordzhonikidze.

The SDLP was banned in Russia so most of its leaders were forced to live in exile. In 1900 the group began publishing a journal called Iskra. It was printed in several European cities and then smuggled into Russia by a network of SDLP agents. Its programme included the overthrow of the tsarist autocracy and the establishment of a democratic republic. (23)

Another group of political activists, including Catherine Breshkovskaya, Victor Chernov, Gregory Gershuni, Alexander Kerensky and Evno Azef, founded the Party of Socialist Revolutionaries (SR) in 1901. The SR rejected the Marxist idea that the peasants were a reactionary class. Its main policy was the confiscation of all land. This would then be distributed among the peasants according to need. The party was also in favour of the establishment of a democratically elected constituent assembly and a maximum 8-hour day for factory workers. "The Socialist Revolutionaries refused, in fact, to recognize any fundamental distinction between workers and peasants: they organized themselves, and with some success, to work among both." (24)

Russo-Japanese War

Although Nicholas II described himself as a man of peace, he favoured an expanded Russian Empire. Encouraged by Vyacheslav Plehve the Tsar made plans to seize Constantinople and expanded into Manchuria and Korea. Japan felt her own interests in the area were being threatened and on 8th February, 1904, the Japanese Navy launched a surprise attack on the Russian fleet at Port Arthur. Although the Russian Army was able to hold back Japanese armies along the Yalu River and in Manchuria, the Russian Navy fared badly in the opening stages of the conflict. (25)

Sergi Witte claimed that Plehve remarked that Russia needed "a little, victorious war to stem the revolution". There are doubts about the truth of this statement but Plehve's actions definitely precipitated the Russo-Japanese War. However, the war failed in its main objective to win support for Nicholas II and the autocracy. The war was unpopular with the Russian people and demonstrations took place in border areas such as Finland, Poland and the Caucasus. Failure to defeat the Japanese also reduced the prestige of the Tsar and his government. (26)

However, it was Plehve's record on human rights that made him so hated by the Russian people. This was especially true of his hatred for the Jews. Theodore Rothstein pointed out: "Plehve was directly responsible for the horrors of Kishineff and Gomel - horrors that remind one of the darkest period of the Middle Ages. If to this be added the numberless other outrages and acts of terrorism committed against various public bodies as well as single individuals who in any way dared to assert their independence of speech or thought, we may well say that there is in modern times but one name that is worthy to rank along with his, and that is the Duke of Alva. Blood at the beginning, blood at the end, blood throughout his career - that is the mark Plehve left behind him in history. He was a living outrage on the moral consciousness of mankind." (27)

Vyacheslav Plehve was much hated by all those seeking reform and in 1904 Evno Azef, head of the Terrorist Brigade of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, ordered his assassination. Plehve was killed by a bomb thrown by Egor Sazonov on 28th July, 1904. Emile J. Dillon, who was working for the Daily Telegraph, witnessed the assassination: "Two men on bicycles glided past, followed by a closed carriage, which I recognized as that of the all-powerful minister (Vyacheslav Plehve). Suddenly the ground before me quivered, a tremendous sound as of thunder deafened me, the windows of the houses on both sides of the broad streets rattled, and the glass of the panes was hurled on to the stone pavements. A dead horse, a pool of blood, fragments of a carriage, and a hole in the ground were parts of my rapid impressions. My driver was on his knees devoutly praying and saying that the end of the world had come.... Plehve's end was received with semi-public rejoicings. I met nobody who regretted his assassination or condemned the authors." (28)

Praskovia Ivanovskaia who took part in the conspiracy later pointed out: "The conclusion of this affair gave me some satisfaction - finally the man who had taken so many victims had been brought to his inevitable end, so universally desired." Dillon claimed that "I met nobody who regretted his assassination or condemned the authors". Lionel Kochan pointed out that "Plehve was the very embodiment of the government's policy of repression, contempt for public opinion, anti-semitism and bureaucratic tyranny". (29)

Plehve was replaced by Pyotr Sviatopolk-Mirsky, as Minister of the Interior. He held liberal views and hoped to use his power to create a more democratic system of government. Sviatopolk-Mirsky believed that Russia should grant the same rights enjoyed in more advanced countries in Europe. He recommended that the government strive to create a "stable and conservative element" among the workers by improving factory conditions and encouraging workers to buy their own homes. "It is common knowledge that nothing reinforces social order, providing it with stability, strength, and ability to withstand alien influences, better than small private owners, whose interests would suffer adversely from all disruptions of normal working conditions." (30)

Assembly of Russian Workers

In February, 1904, Sviatopolk-Mirsky's agents approached Father Georgi Gapon and encouraged him to use his popular following to "direct their grievances into the path of economic reform and away from political discontent". (21) Gapon agreed and on 11th April 1904 he formed the Assembly of Russian Workers of St Petersburg. Its aims were to affirm "national consciousness" amongst the workers, develop "sensible views" regarding their rights and foster amongst the members of the union "activity facilitating the legal improvements of the workers' conditions of work and living". (31)

By the end of 1904 the Assembly had cells in most of the larger factories, including a particularly strong contingent at the Putilov works. The overall membership has been variously estimated between 2,000 and 8,000. Whatever the true figure, the strength of the Assembly and of its sympathizers exceeded by far that of the political parties. For example, in St Petersburg at this time, the local Menshevik and Bolshevik groups could muster no more than 300 members each. (32)

Adam B. Ulam, the author of The Bolsheviks (1998) was highly critical of the leader of the Assembly of Russian Revolution: "Gapon had certain peasant cunning, but was politically illiterate, and his personal tastes were rather inappropriate for either a revolutionary or a priest: he was unusually fond of gambling and drinking. Yet he became an object of a spirited competition among various branches of the radical movement." (33) Another revolutionary figure, Victor Serge, saw him in a much more positive light. "Gapon is a remarkable character. He seems to have believed sincerely in the possibility of reconciling the true interests of the workers with the authorities' good intentions". (34)

According to Cathy Porter: "Despite its opposition to equal pay for women, the Union attracted some three hundred women members, who had to fight a great deal of prejudice from the men to join." Vera Karelina was an early member and led its women's section: "I remember what I had to put up with when there was the question of women joining... There wasn't a single mention of the woman worker, as if she was non-existent, like some sort of appendage, despite the fact that the workers in several factories were exclusively women." Karelina was also a Bolshevik but complained "how little our party concerned itself with the fate of working women, and how inadequate was its interest in their liberation.'' (35)

Adam B. Ulam claimed that the Assembly of Russian Workers of St Petersburg was firmly under the control of the Minister of the Interior: "Father Gapon... had, with the encouragement and subsidies of the police, organized a workers' union, thus continuing the work of Zubatov. The union had scrupulously excluded Socialists and Jews. For a while the police could congratulate themselves on their enterprise." (36) David Shub, a Menshevik, agreed, claiming that the organisation had been set up to "wean the workers away from radicalism". (37)

Alexandra Kollontai, an important Bolshevik leader, did join the union with little difficulty. She was also a feminist and felt the Bolsheviks had not done enough to support the demands of women members. Kollontai believed that any organisation that allowed factory women was preferable to the Bolsheviks' almost total silence about them, and "how little our party concerned itself with the fate of working women, and how inadequate was its interest in their liberation." (38)

1904 was a bad year for Russian workers. Prices of essential goods rose so quickly that real wages declined by 20 per cent. When four members of the Assembly of Russian Workers were dismissed at the Putilov Iron Works in December, Gapon tried to intercede for the men who lost their jobs. This included talks with the factory owners and the governor-general of St Petersburg. When this failed, Gapon called for his members in the Putilov Iron Works to come out on strike. (39)

Father Georgi Gapon demanded: (i) An 8-hour day and freedom to organize trade unions. (ii) Improved working conditions, free medical aid, higher wages for women workers. (iii) Elections to be held for a constituent assembly by universal, equal and secret suffrage. (iv) Freedom of speech, press, association and religion. (v) An end to the war with Japan. By the 3rd January 1905, all 13,000 workers at Putilov were on strike, the department of police reported to the Minister of the Interior. "Soon the only occupants of the factory were two agents of the secret police". (40)

The strike spread to other factories. By the 8th January over 110,000 workers in St. Petersburg were on strike. Father Gapon wrote that: "St Petersburg seethed with excitement. All the factories, mills and workshops gradually stopped working, till at last not one chimney remained smoking in the great industrial district... Thousands of men and women gathered incessantly before the premises of the branches of the Workmen's Association." (41)

Tsar Nicholas II became concerned about these events and wrote in his diary: "Since yesterday all the factories and workshops in St. Petersburg have been on strike. Troops have been brought in from the surroundings to strengthen the garrison. The workers have conducted themselves calmly hitherto. Their number is estimated at 120,000. At the head of the workers' union some priest - socialist Gapon. Mirsky (the Minister of the Interior) came in the evening with a report of the measures taken." (42)

Gapon drew up a petition that he intended to present a message to Nicholas II: "We workers, our children, our wives and our old, helpless parents have come, Lord, to seek truth and protection from you. We are impoverished and oppressed, unbearable work is imposed on us, we are despised and not recognized as human beings. We are treated as slaves, who must bear their fate and be silent. We have suffered terrible things, but we are pressed ever deeper into the abyss of poverty, ignorance and lack of rights." (43)

The petition contained a series of political and economic demands that "would overcome the ignorance and legal oppression of the Russian people". This included demands for universal and compulsory education, freedom of the press, association and conscience, the liberation of political prisoners, separation of church and state, replacement of indirect taxation by a progressive income tax, equality before the law, the abolition of redemption payments, cheap credit and the transfer of the land to the people. (44)

Bloody Sunday

Over 150,000 people signed the document and on 22nd January, 1905, Father Georgi Gapon led a large procession of workers to the Winter Palace in order to present the petition. The loyal character of the demonstration was stressed by the many church icons and portraits of the Tsar carried by the demonstrators. Alexandra Kollontai was on the march and her biographer, Cathy Porter, has described what took place: "She described the hot sun on the snow that Sunday morning, as she joined hundreds of thousands of workers, dressed in their Sunday best and accompanied by elderly relatives and children. They moved off in respectful silence towards the Winter Palace, and stood in the snow for two hours, holding their banners, icons and portraits of the Tsar, waiting for him to appear." (45)

Harold Williams, a journalist working for the Manchester Guardian, also watched the Gapon led procession taking place: "I shall never forget that Sunday in January 1905 when, from the outskirts of the city, from the factory regions beyond the Moscow Gate, from the Narva side, from up the river, the workmen came in thousands crowding into the centre to seek from the tsar redress for obscurely felt grievances; how they surged over the snow, a black thronging mass." (46) The soldiers machine-gunned them down and the Cossacks charged them. (47)

Alexandra Kollontai observed the "trusting expectant faces, the fateful signal of the troops stationed around the Palace, the pools of blood on the snow, the bellowing of the gendarmes, the dead, the wounded, the children shot." She added that what the Tsar did not realise was that "on that day he had killed something even greater, he had killed superstition, and the workers' faith that they could ever achieve justice from him. From then on everything was different and new." (48) It is not known the actual numbers killed but a public commission of lawyers after the event estimated that approximately 150 people lost their lives and around 200 were wounded. (49)

Gapon later described what happened in his book The Story of My Life (1905): "The procession moved in a compact mass. In front of me were my two bodyguards and a yellow fellow with dark eyes from whose face his hard labouring life had not wiped away the light of youthful gaiety. On the flanks of the crowd ran the children. Some of the women insisted on walking in the first rows, in order, as they said, to protect me with their bodies, and force had to be used to remove them. Suddenly the company of Cossacks galloped rapidly towards us with drawn swords. So, then, it was to be a massacre after all! There was no time for consideration, for making plans, or giving orders. A cry of alarm arose as the Cossacks came down upon us. Our front ranks broke before them, opening to right and left, and down the lane the soldiers drove their horses, striking on both sides. I saw the swords lifted and falling, the men, women and children dropping to the earth like logs of wood, while moans, curses and shouts filled the air." (50)

Alexandra Kollontai observed the "trusting expectant faces, the fateful signal of the troops stationed around the Palace, the pools of blood on the snow, the bellowing of the gendarmes, the dead, the wounded, the children shot." She added that what the Tsar did not realise was that "on that day he had killed something even greater, he had killed superstition, and the workers' faith that they could ever achieve justice from him. From then on everything was different and new." It is not known the actual numbers killed but a public commission of lawyers after the event estimated that approximately 150 people lost their lives and around 200 were wounded. (51)

Father Gapon escaped uninjured from the scene and sought refuge at the home of Maxim Gorky: "Gapon by some miracle remained alive, he is in my house asleep. He now says there is no Tsar anymore, no church, no God. This is a man who has great influence upon the workers of the Putilov works. He has the following of close to 10,000 men who believe in him as a saint. He will lead the workers on the true path." (52)

1905 Russian Revolution

The killing of the demonstrators became known as Bloody Sunday and it has been argued that this event signalled the start of the 1905 Revolution. That night the Tsar wrote in his diary: "A painful day. There have been serious disorders in St. Petersburg because workmen wanted to come up to the Winter Palace. Troops had to open fire in several places in the city; there were many killed and wounded. God, how painful and sad." (53)

The massacre of an unarmed crowd undermined the standing of the autocracy in Russia. The United States consul in Odessa reported: "All classes condemn the authorities and more particularly the Tsar. The present ruler has lost absolutely the affection of the Russian people, and whatever the future may have in store for the dynasty, the present tsar will never again be safe in the midst of his people." (54)

The day after the massacre all the workers at the capital's electricity stations came out on strike. This was followed by general strikes taking place in Moscow, Vilno, Kovno, Riga, Revel and Kiev. Other strikes broke out all over the country. Pyotr Sviatopolk-Mirsky resigned his post as Minister of the Interior, and on 19th January, 1905, Tsar Nicholas II summoned a group of workers to the Winter Palace and instructed them to elect delegates to his new Shidlovsky Commission, which promised to deal with some of their grievances. (55)

Lenin, who had been highly suspicious of Father Gapon, admitted that the formation of Assembly of Russian Workers of St Petersburg and the occurrence of Bloody Sunday, had made an important contribution to the development of a radical political consciousness: "The revolutionary education of the proletariat made more progress in one day than it could have made in months and years of drab, humdrum, wretched existence." (56)

Henry Nevinson, of The Daily Chronicle commented that Gapon was "the man who struck the first blow at the heart of tyranny and made the old monster sprawl." When he heard the news of Bloody Sunday Leon Trotsky decided to return to Russia. He realised that Father Gapon had shown the way forward: "Now no one can deny that the general strike is the most important means of fighting. The twenty-second of January was the first political strike, even if he was disguised under a priest's cloak. One need only add that revolution in Russia may place a democratic workers' government in power." (57)

Trotsky believed that Bloody Sunday made the revolution much more likely. One revolutionary noted that the killing of peaceful protestors had changed the political views of many peasants: "Now tens of thousands of revolutionary pamphlets were swallowed up without remainder; nine-tenths were not only read but read until they fell apart. The newspaper which was recently considered by the broad popular masses, and particularly by the peasantry, as a landlord's affair, and when it came accidentally into their hands was used in the best of cases to roll cigarettes in, was now carefully, even lovingly, straightened and smoothed out, and given to the literate." (58)

The SR Combat Organization decided the next man to be assassinated was the Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich. the General-Governor of Moscow and uncle of Tsar Nicholas II. The assassination was planned for 15th February, 1905, when he planned to visit the Bolshoi Theatre. (59) Ivan Kalyayev was supposed to attack the carriage as it approached the theater. Kalyayev was about to throw his bomb at the carriage of the Grand Duke, but he noticed that his wife and two young children were in the carriage and he aborted the assassination. (60)

Ivan Kalyayev carried out the assassination two days later: "I hurled my bomb from a distance of four paces, not more, striking as I dashed forward quite close to my object. I was caught up by the storm of the explosion and saw how the carriage was torn to fragments. When the cloud had lifted I found myself standing before the remains of the back wheels.... Then, about five feet away, near the gate, I saw bits of the Grand Duke's clothing and his nude body.... Blood was streaming from my face, and I realized there would be no escape for me.:.. I was overtaken by the police agents in a sleigh and someone's hands were upon me. 'Don't hang on to me. I won't run away. I have done my work' (I realized now that I was deafened)." (61)

While he was in prison he was visited by the Grand Duke's wife. She asked him "Why did you kill my husband?". He replied "I killed Sergei Alexandrovich because he was a weapon of tyranny. I was taking revenge for the people." The Grand Duchess offered Kalyayev a deal. "Repent... and I will beg the Sovereign to give you your life. I will ask him for you. I myself have already forgiven you." He refused with the words: "'No! I do not repent. I must die for my deed and I will... My death will be more useful to my cause than Sergei Alexandrovich's death." (62)

During his trial Kalyayev defended his actions: "First of all, permit me to make a correction of fact: I am not a defendant here, I am your prisoner. We are two warring camps. You - the representatives of the Imperial Government, the hired servants of capital and oppression. I - one of the avengers of the people, a socialist and revolutionist. Mountains of corpses divide us, hundreds of thousands of broken human lives and a whole sea of blood and tears covering the country in torrents of horror and resentment. You have declared war on the people. We have accepted your challenge." (63)

Ivan Kalyayev was sentenced to death. "I am pleased with your sentence," he told the judges. "I hope that you will carry it out just as openly and publicly as I carried out the sentence of the Socialist Revolutionary Party. Learn to look the advancing revolution right in the face." He was hanged on 23rd May, 1905. (64)

In June, 1905, Sergei Witte was asked to negotiate an end to the Russo-Japanese War. The Nicholas II was pleased with his performance and was brought into the government to help solve the industrial unrest that had followed Bloody Sunday. Witte pointed out: "With many nationalities, many languages and a nation largely illiterate, the marvel is that the country can be held together even by autocracy. Remember one thing: if the tsar's government falls, you will see absolute chaos in Russia, and it will be many a long year before you see another government able to control the mixture that makes up the Russian nation." (65)

Emile J. Dillon, a journalist working for the Daily Telegraph, agreed with Witte's analysis: "Witte... convinced me that any democratic revolution, however peacefully effected, would throw open the gates wide to the forces of anarchism and break up the empire. And a glance at the mere mechanical juxtaposition - it could not be called union - of elements so conflicting among themselves as were the ethnic, social and religious sections and divisions of the tsar's subjects would have brought home this obvious truth to the mind of any unbiased and observant student of politics." (66)

On 27th June, 1905, sailors on the Potemkin battleship, protested against the serving of rotten meat infested with maggots. The captain ordered that the ringleaders to be shot. The firing-squad refused to carry out the order and joined with the rest of the crew in throwing the officers overboard. The mutineers killed seven of the Potemkin's eighteen officers, including Captain Evgeny Golikov. They organized a ship's committee of 25 sailors, led by Afanasi Matushenko, to run the battleship. (67)

A delegation of the mutinous sailors arrived in Geneva with a message addressed directly to Father Gapon. He took the cause of the sailors to heart and spent all his time collecting money and purchasing supplies for them. He and their leader, Afanasi Matushenko, became inseparable. "Both were of peasant origin and products of the mass upheaval of 1905 - both were out of place among the party intelligentsia of Geneva." (68)

The Potemkin Mutiny spread to other units in the army and navy. Industrial workers all over Russia withdrew their labour and in October, 1905, the railwaymen went on strike which paralyzed the whole Russian railway network. This developed into a general strike. Leon Trotsky later recalled: "After 10th October 1905, the strike, now with political slogans, spread from Moscow throughout the country. No such general strike had ever been seen anywhere before. In many towns there were clashes with the troops." (69)

Sergei Witte, his Chief Minister, saw only two options open to the Tsar, "either he must put himself at the head of the popular movement for freedom by making concessions to it, or he must institute a military dictatorship and suppress by naked force for the whole of the opposition". However, he pointed out that any policy of repression would result in "mass bloodshed". His advice was that the Tsar should offer a programme of political reform. (70)

On 22nd October, 1905, Sergei Witte sent a message to the Tsar: "The present movement for freedom is not of new birth. Its roots are imbedded in centuries of Russian history. Freedom must become the slogan of the government. No other possibility for the salvation of the state exists. The march of historical progress cannot be halted. The idea of civil liberty will triumph if not through reform then by the path of revolution. The government must be ready to proceed along constitutional lines. The government must sincerely and openly strive for the well-being of the state and not endeavour to protect this or that type of government. There is no alternative. The government must either place itself at the head of the movement which has gripped the country or it must relinquish it to the elementary forces to tear it to pieces." (71)

Nicholas II became increasingly concerned about the situation and entered into talks with Sergi Witte. As he pointed out: "Through all these horrible days, I constantly met Witte. We very often met in the early morning to part only in the evening when night fell. There were only two ways open; to find an energetic soldier and crush the rebellion by sheer force. That would mean rivers of blood, and in the end we would be where had started. The other way out would be to give to the people their civil rights, freedom of speech and press, also to have laws conformed by a State Duma - that of course would be a constitution. Witte defends this very energetically." (72)

Grand Duke Nikolai Romanov, the second cousin of the Tsar, was an important figure in the military. He was highly critical of the way the Tsar dealt with these incidents and favoured the kind of reforms favoured by Sergi Witte: "The government (if there is one) continues to remain in complete inactivity... a stupid spectator to the tide which little by little is engulfing the country." (73)

While discussions continued the scale of political unrest grew. Setting fire to the estates of the nobility. There were so many cases that it was impossible to impose on offenders that the punishment decreed earlier in the year, the confiscated of their land. According to one report this action "would have led to the formation of vagabond gangs and, of course, would only have strengthened the peasant movement". Catherine Breshkovskaya, one of the leaders of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, commented, "at night ominous pillars of flame could be seen in all directions". (74)

Later that month, Trotsky and other Mensheviks established the St. Petersburg Soviet. On 26th October the first meeting of the Soviet took place in the Technological Institute. It was attended by only forty delegates as most factories in the city had time to elect the representatives. It published a statement that claimed: "In the next few days decisive events will take place in Russia, which will determine for many years the fate of the working class in Russia. We must be fully prepared to cope with these events united through our common Soviet." (75)

Over the next few weeks over 50 of these soviets were formed all over Russia and these events became known as the 1905 Revolution. Witte continued to advise the Tsar to make concessions. The Grand Duke Nikolai Romanov agreed and urged the Tsar to bring in reforms. The Tsar refused and instead ordered him to assume the role of a military dictator. The Grand Duke drew his pistol and threatened to shoot himself on the spot if the Tsar did not endorse Witte's plan. (76)

The Duma

On 30th October, the Tsar reluctantly agreed to publish details of the proposed reforms that became known as the October Manifesto. This granted freedom of conscience, speech, meeting and association. He also promised that in future people would not be imprisoned without trial. Finally it announced that no law would become operative without the approval of the State Duma. It has been pointed out that "Witte sold the new policy with all the forcefulness at his command". He also appealed to the owners of the newspapers in Russia to "help me to calm opinions". (77)

These proposals were rejected by the St. Petersburg Soviet: "We are given a constitution, but absolutism remains... The struggling revolutionary proletariat cannot lay down its weapons until the political rights of the Russian people are established on a firm foundation, until a democratic republic is established, the best road for the further progress to Socialism." (78)

The first meeting of the Duma took place in May 1906. A British journalist, Maurice Baring, described the members taking their seats on the first day: "Peasants in their long black coats, some of them wearing military medals... You see dignified old men in frock coats, aggressively democratic-looking men with long hair... members of the proletariat... dressed in the costume of two centuries ago... There is a Polish member who is dressed in light-blue tights, a short Eton jacket and Hessian boots... There are some socialists who wear no collars and there is, of course, every kind of headdress you can conceive." (79)

Several changes in the composition of the Duma had been changed since the publication of the October Manifesto. Nicholas II had also created a State Council, an upper chamber, of which he would nominate half its members. He also retained for himself the right to declare war, to control the Orthodox Church and to dissolve the Duma. The Tsar also had the power to appoint and dismiss ministers. At their first meeting, members of the Duma put forward a series of demands including the release of political prisoners, trade union rights and land reform. The Tsar rejected all these proposals and dissolved the Duma. (80)

In April, 1906, Nicholas II forced Sergi Witte to resign and asked the more conservative Peter Stolypin to become Chief Minister. Stolypin was the former governor of Saratov and his draconian measures in suppressing the peasants in 1905 made him notorious. At first he refused the post but the Tsar insisted: "Let us make the sign of the Cross over ourselves and let us ask the Lord to help us both in this difficult, perhaps historic moment." Stolypin told Bernard Pares that "an assembly representing the majority of the population would never work". (81)

Stolypin attempted to provide a balance between the introduction of much needed land reforms and the suppression of the radicals. In October, 1906, Stolypin introduced legislation that enabled peasants to have more opportunity to acquire land. They also got more freedom in the selection of their representatives to the Zemstvo (local government councils). "By avoiding confrontation with peasant representatives in the Duma, he was able to secure the privileges attached to nobles in local government and reject the idea of confiscation." (82)

However, he also introduced new measures to repress disorder and terrorism. On 25 August 1906, three assassins wearing military uniforms, bombed a public reception Stolypin was holding at his home on Aptekarsky Island. Stolypin was only slightly injured, but 28 others were killed. Stolypin's 15-year-old daughter had both legs broken and his 3-year-old son also had injuries. The Tsar suggested that the Stolypin family moved into the Winter Palace for protection. (83)

Elections for the Second Duma took place in 1907. Peter Stolypin, used his powers to exclude large numbers from voting. This reduced the influence of the left but when the Second Duma convened in February, 1907, it still included a large number of reformers. After three months of heated debate, Nicholas II closed down the Duma on the 16th June, 1907. He blamed Lenin and his fellow-Bolsheviks for this action because of the revolutionary speeches that they had been making in exile. (84)

Members of the moderate Constitutional Democrat Party (Kadets) were especially angry about this decision. The leaders, including Prince Georgi Lvov and Pavel Milyukov, travelled to Vyborg, a Finnish resort town, in protest of the government. Milyukov drafted the Vyborg Manifesto. In the manifesto, Milyukov called for passive resistance, non-payment of taxes and draft avoidance. Stolypin took revenge on the rebels and "more than 100 leading Kadets were brought to trial and suspended from their part in the Vyborg Manifesto." (85)

Stolypin's repressive methods created a great deal of conflict. Lionel Kochan, the author of Russia in Revolution (1970), pointed out: "Between November 1905 and June 1906, from the ministry of the interior alone, 288 persons were killed and 383 wounded. Altogether, up to the end of October 1906, 3,611 government officials of all ranks, from governor-generals to village gendarmes, had been killed or wounded." (86) Stolypin told his friend, Bernard Pares, that "in no country is the public more anti-governmental than in Russia". (87)

The Russian government considered Germany to be the main threat to its territory. This was reinforced by Germany's decision to form the Triple Alliance. Under the terms of this military alliance, Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy agreed to support each other if attacked by either France or Russia. Although Germany was ruled by the Tsar's cousin, Kaiser Wilhem II, he accepted the views of his ministers and in 1907 agreed that Russia should joined Britain and France to form the Triple Entente.

Peter Stolypin instituted a new court system that made it easier for the arrest and conviction of political revolutionaries. In the first six months of their existence the courts passed 1,042 death sentences. It has been claimed that over 3,000 suspects were convicted and executed by these special courts between 1906 and 1909. As a result of this action the hangman's noose in Russia became known as "Stolypin's necktie". (88)

Peter Stolypin now made changes to the electoral law. This excluded national minorities and dramatically reduced the number of people who could vote in Poland, Siberia, the Caucasus and in Central Asia. The new electoral law also gave better representation to the nobility and gave greater power to the large landowners to the detriment of the peasants. Changes were also made to the voting in towns and now those owning their own homes elected over half the urban deputies.

In 1907 Stolypin introduced a new electoral law, by-passing the 1906 constitution, which assured a right-wing majority in the Duma. The Third Duma met on 14th November 1907. The former coalition of Socialist-Revolutionaries, Mensheviks, Bolsheviks, Octobrists and Constitutional Democrat Party, were now outnumbered by the reactionaries and the nationalists. Unlike the previous Dumas, this one ran its full-term of five years.

The revolutionaries were now determined to assassinate Stolypin and there were several attempts on his life. "He wore a bullet-proof vest and surrounded himself with security men - but he seemed to expect nevertheless that he would eventually die violently." The first line of his will, written shortly after he had become Prime Minister, read: "Bury me where I am assassinated." (89)

On 1st September, 1911, Peter Stolypin was assassinated by Dmitri Bogrov, a member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, at the Kiev Opera House. Nicholas II was with him at the time: "During the second interval we had just left the box, as it was so hot, when we heard two sounds as if something had been dropped. I thought an opera glass might have fallen on somebody's head and ran back into the box to look. To the right I saw a group of officers and other people. They seemed to be dragging someone along. Women were shrieking and, directly in front of me in the stalls, Stolypin was standing. He slowly turned his face towards me and with his left hand made the sign of the Cross in the air. Only then did I notice he was very pale and that his right hand and uniform were bloodstained. He slowly sank into his chair and began to unbutton his tunic. People were trying to lynch the assassin. I am sorry to say the police rescued him from the crowd and took him to as isolated room for his first examination." (90)

Grigori Rasputin

Grigori Rasputin, the son of a Russian peasant, arrived in St. Petersburg in 1903, Rasputin met Hermogen, the Bishop of Saratov. He was impressed by Rasputin's healing powers and introduced him to Nicholas II and his wife, Alexandra Fedorovna. The Tsar's only son, Alexei, suffered from haemophilia (a disease whereby the blood does not clot if a wound occurs). When Alexei was taken seriously ill in 1908, Rasputin was called to the royal palace. He managed to stop the bleeding and from then on he became a member of the royal entourage. (91)

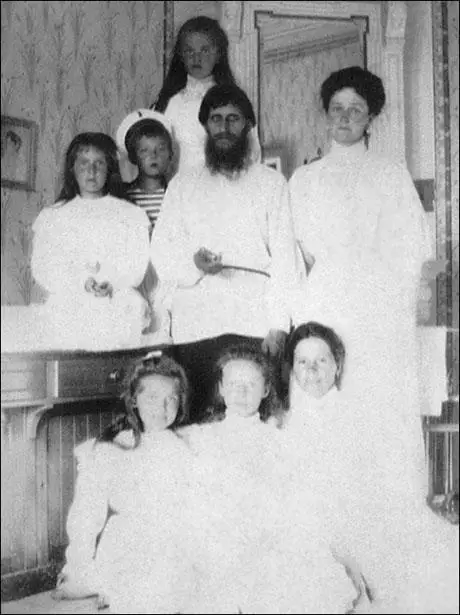

the family nurse Maria Ivanova Vishnyakova (1908)

The Tsarina was completely convinced by the supernatural power of Rasputin. "In their despair at the inability of orthodox medicine to overcome or alleviate the disease, the imperial couple turned with relief to Rasputin... She attached physical power to objects handled by Rasputin. She sent Rasputin's stick and comb to the tsar so that he might benefit from Grigori's vigour when attending ministerial councils." (92)

The Tsarina became very dependent on Rasputin. One one occasion, when he had to spend time outside St. Petersburg, she wrote: "How distraught I am without you. My soul is only at peace, I only rest, when you, my teacher, are seated beside me and I kiss your hands and lean my head on your blessed shoulders... Then I only have one wish: to sleep for centuries on your shoulders, in the embraces." (93)

Ariadna Tyrkova, the wife of the British journalist, Harold Williams, wrote: "Throughout Russia, both at the front and at home, rumour grew ever louder concerning the pernicious influence exercised by the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, at whose side rose the sinister figure of Gregory Rasputin. This charlatan and hypnotist had wormed himself into the Tsar’s palace and gradually acquired a limitless power over the hysterical Empress, and through her over the Sovereign. Rasputin’s proximity to the Tsar’s family proved fatal to the dynasty, for no political criticism can harm the prestige of Tsars so effectually as the personal weakness, vice, or debasement of the members of a royal house." (94)

On 12 July, 1914, a 33-year-old peasant woman named Chionya Guseva attempted to assassinate Grigori Rasputin by stabbing him in the stomach outside his home in Pokrovskoye. Rasputin was seriously wounded and a local doctor who performed emergency surgery saved his life. Guseva claimed to have acted alone, having read about Rasputin in the newspapers and believing him to be a "false prophet and even an Antichrist." (95)

In February 1914, Tsar Nicholas II accepted the advice of his foreign minister, Sergi Sazonov, and committed Russia to supporting the Triple Entente. Sazonov was of the opinion that in the event of a war, Russia's membership of the Triple Entente would enable it to make territorial gains from neighbouring countries. Sazonov sent a telegram to the Russian ambassador in London asking him to make clear to the British government that the Tsar was committed to a war with Germany. "The peace of the world will only be secure on the day when the Triple Entente, whose real existence is not better authenticated than the existence of the sea serpent, shall transform itself into a defensive alliance without secret clauses and publicly announced in all the world press. On that day the danger of a German hegemony will be finally removed, and each one of us will be able to devote himself quietly to his own affairs." (96)

In the international crisis that followed the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, the Tsar made it clear that he was willing to go to war over this issue, Rasputin was an outspoken critic of this policy and joined forces with two senior figures, Sergei Witte and Pyotr Durnovo, to prevent the war. Durnovo told the Tsar that a war with Germany would be "mutually dangerous" to both countries, no matter who won. Witte added that "there must inevitably break out in the conquered country a social revolution, which by the very nature of things, will spread to the country of the victor." (97)

Sergei Witte realised that because of its economic situation, Russia would lose a war with any of its rivals. Bernard Pares met Witte and Rasputin several times in the years leading up to the First World War: "Count Witte never swerved from his conviction, firstly, that Russia must avoid the war at all costs, and secondly, that she must work for economic friendship with France and Germany to counteract the preponderance of England. Rasputin was opposed to the war for reasons as good as Witte's. He was for peace between all nations and between all religions." (98)

Outbreak of the First World War

On the outbreak of the First World War General Alexander Samsonov was given command of the Russian Second Army for the invasion of East Prussia. He advanced slowly into the south western corner of the province with the intention of linking up with General Paul von Rennenkampf advancing from the north east. General Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff were sent forward to meet Samsonov's advancing troops. They made contact on 22nd August, 1914, and for six days the Russians, with their superior numbers, had a few successes. However, by 29th August, Samsanov's Second Army was surrounded. (99)

General Samsonov attempted to retreat but now in a German cordon, most of his troops were slaughtered or captured. The Battle of Tannenberg lasted three days. Only 10,000 of the 150,000 Russian soldiers managed to escape. Shocked by the disastrous outcome of the battle, Samsanov committed suicide. The Germans, who lost 20,000 men in the battle, were able to take over 92,000 Russian prisoners. On 9th September, 1914, General von Rennenkampf ordered his remaining troops to withdraw. By the end of the month the German Army had regained all the territory lost during the initial Russian onslaught. The attempted invasion of Prussia had cost Russia almost a quarter of a million men. (100)

By December, 1914, the Russian Army had 6,553,000 men. However, they only had 4,652,000 rifles. Untrained troops were ordered into battle without adequate arms or ammunition. "Untrained troops were ordered into battle without adequate arms or ammunition. And because the Russian Army had about one surgeon for every 10,000 men, many wounded of its soldiers died from wounds that would have been treated on the Western Front. With medical staff spread out across a 500 mile front, the likelihood of any Russian soldier receiving any medical treatment was close to zero". (101)

Tsar Nicholas II decided to replace Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolayevich Romanov as supreme commander of the Russian Army fighting on the Eastern Front. He was disturbed when he received the following information from General Alexei Brusilov: "In recent battles a third of the men had no rifles. These poor devils had to wait patiently until their comrades fell before their eyes and they could pick up weapons. The army is drowning in its own blood." (102)

Alexander Kerensky complained that: "The Tsarina's blind faith in Rasputin led her to seek his counsel not only in personal matters but also on questions of state policy. General Alekseyev, held in high esteem by Nicholas II, tried to talk to the Tsarina about Rasputin, but only succeeded in making an implacable enemy of her. General Alexseyev told me later about his profound concern on learning that a secret map of military operations had found its way into the Tsarina's hands. But like many others, he was powerless to take any action." (103)

Surely the Germans will not get this far!.

The Tsar: But when our own army returns....?

K. J. Chamberlain, The Masses (January, 1915)

As the Tsar spent most of his time at GHQ, Alexandra Fedorovna now took responsibility for domestic policy. Rasputin served as her adviser and over the next few months she dismissed ministers and their deputies in rapid succession. In letters to her husband she called his ministers as "fools and idiots". According to David Shub "the real ruler of Russia was the Empress Alexandra". (104)

On 7th July, 1915, the Tsar wrote to his wife and complained about the problems he faced fighting the war: "Again that cursed question of shortage of artillery and rifle ammunition - it stands in the way of an energetic advance. If we should have three days of serious fighting we might run out of ammunition altogether. Without new rifles it is impossible to fill up the gaps.... If we had a rest from fighting for about a month our condition would greatly improve. It is understood, of course, that what I say is strictly for you only. Please do not say a word to anyone." (105)

In 1916 two million Russian soldiers were killed or seriously wounded and a third of a million were taken prisoner. Millions of peasants were conscripted into the Tsar's armies but supplies of rifles and ammunition remained inadequate. It is estimated that one third of Russia's able-bodied men were serving in the army. The peasants were therefore unable to work on the farms producing the usual amount of food. By November, 1916, food prices were four times as high as before the war. As a result strikes for higher wages became common in Russia's cities. (106)

The Assassination of Rasputin

Rumours began to circulate that Rasputin and Alexandra Fedorovna were leaders of a pro-German court group and were seeking a separate peace with the Central Powers. This upset Michael Rodzianko, the President of the Duma, and he told Nicholas II: "I must tell Your Majesty that this cannot continue much longer. No one opens your eyes to the true role which this man (Rasputin) is playing. His presence in Your Majesty's Court undermines confidence in the Supreme Power and may have an evil effect on the fate of the dynasty and turn the hearts of the people from their Emperor." (107)

Mansfield Smith-Cumming, the head of MI6, became very concerned by the influence Rasputin was having on Russia's foreign policy. Samuel Hoare was assigned to the British intelligence mission with the Russian general staff. Soon afterwards he was given the rank of lieutenant-colonel and Mansfield Smith-Cumming appointed him as head of the British Secret Intelligence Service in Petrograd. Other members of the unit included Oswald Rayner, Cudbert Thornhill, John Scale and Stephen Alley. One of their main tasks was to deal with Rasputin who was considered to be "one of the most potent of the baleful Germanophil forces in Russia." (108)

The main fear was that Russia might negotiate a separate peace with Germany, thereby releasing the seventy German divisions tied down on the Eastern Front. One MI6 agent wrote: "German intrigue was becoming more intense daily. Enemy agents were busy whispering of peace and hinting how to get it by creating disorder, rioting, etc. Things looked very black. Romania was collapsing, and Russia herself seemed weakening. The failure in communications, the shortness of foods, the sinister influence which seemed to be clogging the war machine, Rasputin the drunken debaucher influencing Russia's policy, what was to the be the end of it all?" (109)

Samuel Hoare reported in December 1916 that poor leadership and inadequate weaponry had led to Russian war fatigue: "I am confident that Russia will never fight through another winter." In another dispatch to headquarters Hoare suggested that if the Tsar banished Rasputin "the country would be freed from the sinister influence that was striking down to natural leaders and endangering the success of its armies in the field." Giles Milton, the author of Russian Roulette: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin's Global Plot (2013) argues that it was at this point that MI6 made plans to assassinate Rasputin. (110)

At the same time Vladimir Purishkevich, the leader of the monarchists in the Duma, was also attempted to organize the elimination of Rasputin. He wrote to Prince Felix Yusupov: "I'm terribly busy working on a plan to eliminate Rasputin. That is simply essential now, since otherwise everything will be finished... You too must take part in it. Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov knows all about it and is helping. It will take place in the middle of December, when Dmitri comes back... Not a word to anyone about what I've written." (111)

Yusupov replied the following day: "Many thanks for your mad letter. I could not understand half of it, but I can see that you are preparing for some wild action.... My chief objection is that you have decided upon everything without consulting me... I can see by your letter that you are wildly enthusiastic, and ready to climb up walls... Don't you dare do anything without me, or I shall not come at all!" (112)

Eventually, Vladimir Purishkevich and Felix Yusupov agreed to work together to kill Rasputin. Three other men Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov, Dr. Stanislaus de Lazovert and Lieutenant Sergei Mikhailovich Sukhotin, an officer in the Preobrazhensky Regiment, joined the plot. Lazovert was responsible for providing the cyanide for the wine and the cakes. He was also asked to arrange for the disposal of the body. (113)

Yusupov later admitted in Lost Splendor (1953) that on 29th December, 1916, Rasputin was invited to his home: "The bell rang, announcing the arrival of Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov and my other friends. I showed them into the dining room and they stood for a little while, silently examining the spot where Rasputin was to meet his end. I took from the ebony cabinet a box containing the poison and laid it on the table. Dr Lazovert put on rubber gloves and ground the cyanide of potassium crystals to powder. Then, lifting the top of each cake, he sprinkled the inside with a dose of poison, which, according to him, was sufficient to kill several men instantly. There was an impressive silence. We all followed the doctor's movements with emotion. There remained the glasses into which cyanide was to be poured. It was decided to do this at the last moment so that the poison should not evaporate and lose its potency." (114)

Vladimir Purishkevich supported this story in his book, The Murder of Rasputin (1918): "We sat down at the round tea table and Yusupov invited us to drink a glass of tea and to try the cakes before they had been doctored. The quarter of an hour which we spent at the table seemed like an eternity to me.... Yusupov gave Dr Lazovert several pieces of the potassium cyanide and he put on the gloves which Yusupov had procured and began to grate poison into a plate with a knife. Then picking out all the cakes with pink cream (there were only two varieties, pink and chocolate), he lifted off the top halves and put a good quantity of poison in each one, and then replaced the tops to make them look right. When the pink cakes were ready, we placed them on the plates with the brown chocolate ones. Then, we cut up two of the pink ones and, making them look as if they had been bitten into, we put these on different plates around the table." (115)

Lazovert now went out to collect Rasputin in his car on the evening of 29th December, 1916. While the other four men waited at the home of Yusupov. According to Lazovert: "At midnight the associates of the Prince concealed themselves while I entered the car and drove to the home of the monk. He admitted me in person. Rasputin was in a gay mood. We drove rapidly to the home of the Prince and descended to the library, lighted only by a blazing log in the huge chimney-place. A small table was spread with cakes and rare wines - three kinds of the wine were poisoned and so were the cakes. The monk threw himself into a chair, his humour expanding with the warmth of the room. He told of his successes, his plots, of the imminent success of the German arms and that the Kaiser would soon be seen in Petrograd. At a proper moment he was offered the wine and the cakes. He drank the wine and devoured the cakes. Hours slipped by, but there was no sign that the poison had taken effect. The monk was even merrier than before. We were seized with an insane dread that this man was inviolable, that he was superhuman, that he couldn't be killed. It was a frightful sensation. He glared at us with his black, black eyes as though he read our minds and would fool us." (116)

Vladimir Purishkevich later recalled that Felix Yusupov joined them upstairs and exclaimed: "It is impossible. Just imagine, he drank two glasses filled with poison, ate several pink cakes and, as you can see, nothing has happened, absolutely nothing, and that was at least fifteen minutes ago! I cannot think what we can do... He is now sitting gloomily on the divan and the only effect that I can see of the poison is that he is constantly belching and that he dribbles a bit. Gentlemen, what do you advise that I do?" Eventually it was decided that Yusupov should go down and shoot Rasputin. (117)

Yusupov later recalled : "I looked at my victim with dread, as he stood before me, quiet and trusting.... Rasputin stood before me motionless, his head bent and his eyes on the crucifix. I slowly raised the crucifix. I slowly raised the revolver. Where should I aim, at the temple or at the heart? A shudder swept over me; my arm grew rigid, I aimed at his heart and pulled the trigger. Rasputin gave a wild scream and crumpled up on the bearskin. For a moment I was appalled to discover how easy it was to kill a man. A flick of a finger and what had been a living, breathing man only a second before, now lay on the floor like a broken doll." (118)

Stanislaus de Lazovert agrees with this account except that he was uncertain who fired the shot: "With a frightful scream Rasputin whirled and fell, face down, on the floor. The others came bounding over to him and stood over his prostrate, writhing body. We left the room to let him die alone, and to plan for his removal and obliteration. Suddenly we heard a strange and unearthly sound behind the huge door that led into the library. The door was slowly pushed open, and there was Rasputin on his hands and knees, the bloody froth gushing from his mouth, his terrible eyes bulging from their sockets. With an amazing strength he sprang toward the door that led into the gardens, wrenched it open and passed out." Lazovert added that it was Vladimir Purishkevich who fired the next shot: "As he seemed to be disappearing in the darkness, Purishkevich, who had been standing by, reached over and picked up an American-made automatic revolver and fired two shots swiftly into his retreating figure. We heard him fall with a groan, and later when we approached the body he was very still and cold and - dead." (119)

Felix Yusupov added: "Rasputin lay on his back. His features twitched in nervous spasms; his hands were clenched, his eyes closed. A bloodstain was spreading on his silk blouse. A few minutes later all movement ceased. We bent over his body to examine it. The doctor declared that the bullet had struck him in the region of the heart. There was no possibility of doubt: Rasputin was dead. We turned off the light and went up to my room, after locking the basement door." (120)

The Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov drove the men to Varshavsky Rail Terminal where they burned Rasputin's clothes. "It was very late and the grand duke evidently feared that great speed would attract the suspicion of the police." They also collected weights and chains and returned to Yusupov's home. At 4.50 a.m. Romanov drove the men and Rasputin's body to Petrovskii Bridge. that crossed towards Krestovsky Island. According to Vladimir Purishkevich: "We dragged Rasputin's corpse into the grand duke's car." Purishkevich claimed he drove very slowly: "It was very late and the grand duke evidently feared that great speed would attract the suspicion of the police." (121) Stanislaus de Lazovert takes up the story when they arrived at Petrovskii: "We bundled him up in a sheet and carried him to the river's edge. Ice had formed, but we broke it and threw him in. The next day search was made for Rasputin, but no trace was found." (122)

The following day the Tsarina wrote to her husband about the disappearance of Rasputin: "We are sitting here together - can you imagine our feelings - our friend has disappeared. Felix Yusupov pretends he never came to the house and never asked him." (123) The next day she wrote: "No trace yet... the police are continuing the search... I fear that these two wretched boys (Felix Yusupov and Dmitri Romanov) have committed a frightful crime but have not yet lost all hope." (124)

Rasputin's body was found on 19th December by a river policeman who was walking on the ice. He noticed a fur coat trapped beneath, approximately 65 metres from the bridge. The ice was cut open and Rasputin's frozen body discovered. The post mortem was held the following day. Major-General Popel carried out the investigation of the murder. By this time Dr. Stanislaus de Lazovert and Lieutenant Sergei Mikhailovich Sukhotin had fled from the city. He did interview Felix Yusupov, Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov and Vladimir Purishkevich, but he decided not to charge them with murder. (125)

Tsar Nicholas II ordered the three men to be expelled from Petrograd. He rejected a petition to allow the conspirators to stay in the city. He replied that "no one had the right to commit murder." Sophie Buxhoeveden later commented: "Though patriotic feeling was supposed to have been the motive of the murder, it was the first indirect blow at the Emperor's authority, the first spark of insurrection. In short, it was the application of lynch law, the taking of law and judgment forcibly into private hands." (126)

The Provisional Government

As Nicholas II was supreme command of the Russian Army he was linked to the country's military failures and there was a strong decline in his support in Russia. George Buchanan, the British Ambassador in Russia, went to see the Tsar: "I went on to say that there was now a barrier between him and his people, and that if Russia was still united as a nation it was in opposing his present policy. The people, who have rallied so splendidly round their Sovereign on the outbreak of war, had seen how hundreds of thousands of lives had been sacrificed on account of the lack of rifles and munitions; how, owing to the incompetence of the administration there had been a severe food crisis."

Buchanan then went on to talk about Tsarina Alexandra Fedorovna: "I next called His Majesty's attention to the attempts being made by the Germans, not only to create dissension between the Allies, but to estrange him from his people. Their agents were everywhere at work. They were pulling the strings, and were using as their unconscious tools those who were in the habit of advising His Majesty as to the choice of his Ministers. They indirectly influenced the Empress through those in her entourage, with the result that, instead of being loved, as she ought to be, Her Majesty was discredited and accused of working in German interests." (127)

In January 1917, General Aleksandr Krymov returned from the Eastern Front and sought a meeting with Michael Rodzianko, the President of the Duma. Krymov told Rodzianko that the officers and men no longer had faith in Nicholas II and the army was willing to support the Duma if it took control of the government of Russia. "A revolution is imminent and we at the front feel it to be so. If you decide on such an extreme step (the overthrow of the Tsar), we will support you. Clearly there is no other way." Rodzianko was unwilling to take action but he did telegraph the Tsar warning that Russia was approaching breaking point. He also criticised the impact that his wife was having on the situation and told him that "you must find a way to remove the Empress from politics". (128)

The Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich shared the views of Rodzianko and sent a letter to the Tsar: "The unrest grows; even the monarchist principle is beginning to totter; and those who defend the idea that Russia cannot exist without a Tsar lose the ground under their feet, since the facts of disorganization and lawlessness are manifest. A situation like this cannot last long. I repeat once more - it is impossible to rule the country without paying attention to the voice of the people, without meeting their needs, without a willingness to admit that the people themselves understand their own needs." (129)

The First World War was having a disastrous impact on the Russian economy. Food was in short supply and this led to rising prices. By January 1917 the price of commodities in Petrograd had increased six-fold. In an attempt to increase their wages, industrial workers went on strike and in Petrograd people took to the street demanding food. On 11th February, 1917, a large crowd marched through the streets of Petrograd breaking shop windows and shouting anti-war slogans.

Petrograd was a city of 2,700,000 swollen with an influx of of over 393,000 wartime workers. According to Harrison E. Salisbury, in the last ten days of January, the city had received 21 carloads of grain and flour per day instead of the 120 wagons needed to feed the city. Okhrana, the secret police, warned that "with every day the food question becomes more acute and it brings down cursing of the most unbridled kind against anyone who has any connection with food supplies." (130)

Harold Williams, a journalist working for the Daily Chronicle reported details of serious food shortages: "All attention here is concentrated on the food question, which for the moment has become unintelligible. Long queues before the bakers' shops have long been a normal feature of life in the city. Grey bread is now sold instead of white, and cakes are not baked. Crowds wander about the streets, mostly women and boys, with a sprinkling of workmen. Here and there windows are broken and a few bakers' shops looted." (131)

It was reported that in one demonstration in the streets by the Nevsky Prospect, the women called out to the soldiers, "Comrades, take away your bayonets, join us!". The soldiers hesitated: "They threw swift glances at their own comrades. The next moment one bayonet is slowly raised, is slowly lifted above the shoulders of the approaching demonstrators. There is thunderous applause. The triumphant crowd greeted their brothers clothed in the grey cloaks of the soldiery. The soldiers mixed freely with the demonstrators." On 27th February, 1917, the Volynsky Regiment mutinied and after killing their commanding officer "made common cause with the demonstrators". (132)

The President of the Duma, Michael Rodzianko, became very concerned about the situation in the city and sent a telegram to the Tsar: "The situation is serious. There is anarchy in the capital. The Government is paralysed. Transport, food, and fuel supply are completely disorganised. Universal discontent is increasing. Disorderly firing is going on in the streets. Some troops are firing at each other. It is urgently necessary to entrust a man enjoying the confidence of the country with the formation of a new Government. Delay is impossible. Any tardiness is fatal. I pray God that at this hour the responsibility may not fall upon the Sovereign." (133)