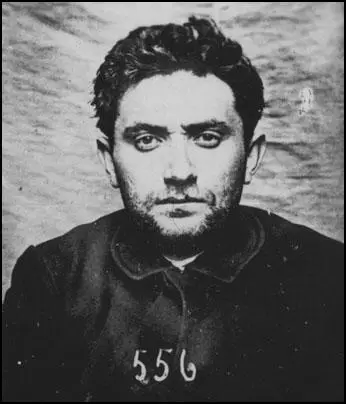

Gregory Zinoviev

Gregory Zinoviev was born in Yelizavetgrad, Ukraine, Russia on 23rd September, 1883. The son of a Jewish diary farmers, Zinoviev received no formal schooling and was educated at home. At the age of fourteen he found work as a clerk.

Zinoviev joined the Social Democratic Party in 1901. He became involved in trade union activities and as a result of police persecution he left Russia and went to live in Berlin before moving on to Paris. In 1903 Zinoviev met Vladimir Lenin and George Plekhanov in Switzerland.

At the Second Congress of the Social Democratic Party in London in 1903, there was a dispute between Vladimir Lenin and Jules Martov, two of the party's main leaders. Lenin argued for a small party of professional revolutionaries with alarge fringe of non-party sympathisers and supporters. Martov disagreed believing it was better to have a large party of activists. Martov won the vote 28-23 but Lenin was unwilling to accept the result and formed a faction known as the Bolsheviks. Those who remained loyal to Martov became known as Mensheviks.

Leon Trotsky, who got to know him during this period compared him to Lev Kamenev: "Zinoviev and Kamenev are two profoundly different types. Zinoviev is an agitator. Kamenev a propagandist. Zinoviev was guided in the main by a subtle political instinct. Kamenev was given to reasoning and analyzing. Zinoviev was always inclined to fly off at a tangent. Kamenev, on the contrary, erred on the side of excessive caution. Zinoviev was entirely absorbed by politics, cultivating no other interests and appetites. In Kamenev there sat a sybarite and a aesthete. Zinoviev was vindictive. Kamenev was good nature personified."

Zinoviev joined the Bolsheviks. So also did Lev Kamenev, Anatoli Lunacharsky, Joseph Stalin, Mikhail Lashevich, Nadezhda Krupskaya, Alexei Rykov, Yakov Sverdlov, Mikhail Frunze, Maxim Litvinov, Vladimir Antonov, Felix Dzerzhinsky, Gregory Ordzhonikidze, and Alexander Bogdanov. Whereas George Plekhanov, Pavel Axelrod, Leon Trotsky, Lev Deich, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, Irakli Tsereteli, Moisei Uritsky, Noi Zhordania and Fedor Dan supported Jules Martov.

In the autumn of 1903 Zinoviev returned to Russia where he became involved in the publication of Iskra. The following year he moved to Switzerland where he studied chemistry at Berne University. He also continued to contribute to Bolshevik journals such as Vperyod.

With the outbreak of the 1905 Revolution Zinoviev returned to Russia and helped organize the general strike in St. Petersburg. Taken seriously ill with heart trouble, Zinoviev was forced to abandon the struggle and receive treatment abroad. Zinoviev returned to Russia in March, 1906, and over the next three years agitated amongst metalworkers in St. Petersburg. As one of the key leaders of the Bolsheviks, Zinoviev was involved in the struggle with the Mensheviks for control over the workers and the armed forces in the city.

In 1907 Zinoviev attended the London Party Congress and was elected to the six man Bolshevik Central Committee. The following year Zinoviev was arrested by the Okhrana but was later released without charge. Afraid of being re-arrested, Zinoviev moved to Geneva where he worked with Vladimir Lenin and Lev Kamenev in the publication of Proletary. Although living in exile, he helped to organize the publication of Zvezda and Pravda in St. Petersburg.

In 1912 Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev and Vladimir Lenin moved to Krakow in Galicia to be closer to Russia. On the outbreak of the First World War they were forced to move to the neutral Switzerland.

After the overthrow of Nicholas II in 1917, Zinoviev, Vladimir Lenin and Lev Kamenev returned to Russia and joined with Leon Trotsky and others in plotting against the government being led by Alexander Kerensky. Soon after arriving in St. Petersburg, Lenin and Zinoviev published their views on how to achieve a Marxist revolution. Zinoviev also became the new editor of Pravda.

The Bolshevik Party feared that Zinoviev and Vladimir Lenin would be arrested and so on the 9th July, 1917, they went into hiding. Zinoviev returned in August and worked for Proletary and Rabachii Put. At a meeting of the Central Committee on 9th October, Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev were the only members opposed to Lenin's call for revolution. He later changed his mind and took part in the October Revolution that brought the Bolsheviks to power.

In February, 1917, Zinoviev was elected Chairman of the Council of Commissars of the Petrograd Workers' Commune. The following month he became Chairman of the Council of Commissars of the Union of Communes of the Northern Region. At the First World Congress of the Comintern in March, 1919, he was elected chairman of the Executive Committee.

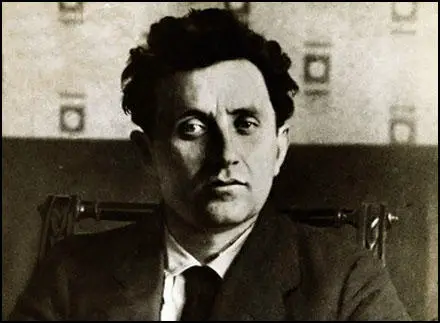

Zinoviev reached the peak of his power in 1923 when with Joseph Stalin and Lev Kamenev became one of the Triumvirate that planned to take over from Vladimir Lenin when he died. Victor Serge commented: "Zinoviev, a collaborator of Lenin's since 1907, theoretician, popularizer and orator, is defending, at Petrograd, one of the most advanced and most threatened outposts of the Republic. As President of the Executive Committee of the Northern Commune, he is the dictator of a great workers's city, starving, cholera-stricken and vulnerable to surprise attack. Zinoviev, with his tousled head, smooth, rather flabby face, nonchalent stance, rounded gestures, deep, sometimes strident and always audible voice, Zinoviev, with his merciless choice of words often confronts and subdues, in the old capital's factories, the discontent and anger of a proletariat whose best sons are at the front, and which is dying of hunger."

After the death of Lenin 1924, Zinoviev joined forces with Lev Kamenev and Joseph Stalin to keep Leon Trotsky from power. In 1925 Stalin was able to arrange for Trotsky to be dismissed as commissar of war and the following year the Politburo. With the decline of Trotsky, Stalin felt strong enough to stop sharing power with Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev. Stalin now began to attack Trotsky's belief in the need for world revolution. He argued that the party's main priority should be to defend the communist system that had been developed in the Soviet Union. This put Zinoviev and Kamenev in an awkward position. They had for a long time been strong supporters of Trotsky's theory that if revolution did not spread to other countries, the communist system in the Soviet Union was likely to be overthrown by hostile, capitalist nations. However, they were reluctant to speak out in favour of a man whom they had been in conflict with for so long.

Louis Fischer, an American journalist who supported Stalin, reported in the Current History Magazine in June, 1925: "One is at a loss sometimes to explain the ascendancy of a man like Gregory Zinoviev.... His mental powers are mediocre, his personality far from being winning, even to his own party colleagues is often repulsive. With his high, monotonous falsetto voice he could not be an orator even if his speeches excelled in style, incision and depth, and this is not generally the case."

When Joseph Stalin was finally convinced that Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev were unwilling to join forces with Leon Trotsky against him, he began to support openly the economic policies of right-wing members of the Politburo like Nikolay Bukharin, Mikhail Tomsky and Alexei Rykov. They now realized what Stalin was up to but it took them to summer of 1926 before they could swallow their pride and join with Trotsky against Stalin.

When Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev eventually began attacking his policies, Joseph Stalin argued they were creating disunity in the party and managed to have them expelled from the Central Committee. The belief that the party would split into two opposing factions was a strong fear amongst active communists in the Soviet Union. They were convinced that if this happened, western countries would take advantage of the situation and invade the Soviet Union.

Under pressure from the Central Committee, Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev agreed to sign statements promising not to create conflict in the movement by making speeches attacking official policies. Leon Trotsky refused to sign and was banished to the remote area of Kazhakstan.

At the 17th Party Congress in 1934, when Sergey Kirov stepped up to the podium he was greeted by spontaneous applause that equalled that which was required to be given to Stalin. In his speech he put forward a policy of reconciliation. He argued that people should be released from prison who had opposed the government's policy on collective farms and industrialization. The members of the Congress gave Kirov a vote of confidence by electing him to the influential Central Committee Secretariat. Stalin grew jealous of Kirov's popularity. As Edward P. Gazur has pointed out: "In sharp contrast to Stalin, Kirov was a much younger man and an eloquent speaker, who was able to sway his listeners; above all, he possessed a charismatic personality. Unlike Stalin who was a Georgian, Kirov was also an ethnic Russian, which stood in his favour."

Kirov put forward a policy of reconciliation. He argued that people should be released from prison who had opposed the government's policy on collective farms and industrialization. Once again, Stalin found himself in a minority in the Politburo. After years of arranging for the removal of his opponents from the party, Stalin realized he still could not rely on the total support of the people whom he had replaced them with. Stalin no doubt began to wonder if Kirov was willing to wait for his mentor to die before becoming leader of the party. Stalin was particularly concerned by Kirov's willingness to argue with him in public, fearing that this would undermine his authority in the party.

As usual, that summer Kirov and Stalin went on holiday together. Stalin, who treated Kirov like a son, used this opportunity to try to persuade him to remain loyal to his leadership. Stalin asked him to leave Leningrad to join him in Moscow. Stalin wanted Kirov in a place where he could keep a close eye on him. When Kirov refused, Stalin knew he had lost control over his protégé.As usual, that summer Kirov and Stalin went on holiday together. Stalin, who treated Kirov like a son, used this opportunity to try to persuade him to remain loyal to his leadership. Stalin asked him to leave Leningrad to join him in Moscow. Stalin wanted Kirov in a place where he could keep a close eye on him. When Kirov refused, Stalin knew he had lost control over his protégé. According to Alexander Orlov, who had been told this by Genrikh Yagoda, Stalin decided that Kirov had to die.

Yagoda assigned the task to Vania Zaporozhets, one of his trusted lieutenants in the NKVD. He selected a young man, Leonid Nikolayev, as a possible candidate. Nikolayev had recently been expelled from the Communist Party and had vowed his revenge by claiming that he intended to assassinate a leading government figure. Zaporozhets met Nikolayev and when he discovered he was of low intelligence and appeared to be a person who could be easily manipulated, he decided that he was the ideal candidate as assassin.

Zaporozhets provided him with a pistol and gave him instructions to kill Kirov in the Smolny Institute in Leningrad. However, soon after entering the building he was arrested. Zaporozhets had to use his influence to get him released. On 1st December, 1934, Nikolayev, got past the guards and was able to shoot Kirov dead. Nikolayev was immediately arrested and after being tortured by Genrikh Yagoda he signed a statement saying that Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev had been the leaders of the conspiracy to assassinate Kirov.

According to Alexander Orlov: "Stalin decided to arrange for the assassination of Kirov and to lay the crime at the door of the former leaders of the opposition and thus with one blow do away with Lenin's former comrades. Stalin came to the conclusion that, if he could prove that Zinoviev and Kamenev and other leaders of the opposition had shed the blood of Kirov". Victor Kravchenko has pointed out: "Hundreds of suspects in Leningrad were rounded up and shot summarily, without trial. Hundreds of others, dragged from prison cells where they had been confined for years, were executed in a gesture of official vengeance against the Party's enemies. The first accounts of Kirov's death said that the assassin had acted as a tool of dastardly foreigners - Estonian, Polish, German and finally British. Then came a series of official reports vaguely linking Nikolayev with present and past followers of Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev and other dissident old Bolsheviks."

Leonid Nikolayev was executed after his trial but Zinoviev and Kamenev refused to confess. Ya S. Agranov, the deputy commissar of the secret police, reported to Stalin he was not able to prove that they had been directly involved in the assassination. Therefore in January 1935 they were tried and convicted only for "moral complicity" in the crime. "That is, their opposition had created a climate in which others were incited to violence." Zinoviev was sentenced to ten years hard labour, Kamenev to five.

Genrikh Yagoda now had the task of persuading Kamenev and Zinoviev to confess to their role in the death of Kirov as part of the plot to assassinate Stalin and other leaders of government. When they refused to do this Stalin had a new provision enacted into law on 8th April 1935 which would enable him to exert additional leverage over his enemies. The new law decreed that children of the age of twelve and over who were found guilty of crimes would be subjected to the same punishment as adults, up to and including the death penalty. This provision provided NKVD with the means by which they could coerce a confession from a political dissident simply by claiming that false charges would be brought against their children.

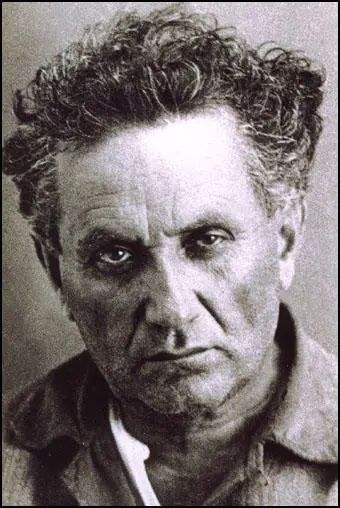

Edward P. Gazur, the author of Alexander Orlov: The FBI's KGB General (2001), claims that Alexander Orlov later admitted: "In the months preceding the trial, the two men were subjected to every conceivable form of interrogation: subtle pressure, then periods of enormous pressure, starvation, open and veiled threats, promises, as well as physical and mental torture. Neither man would succumb to the ordeal they faced." Stalin was frustrated by Stalin's lack of success and brought in Nikolai Yezhov to carry out the interrogations.

Orlov, who was a leading figure in the NKVD, later admitted what happened. "Towards the end of their ordeal, Zinoviev became sick and exhausted. Yezhov took advantage of the situation in a desperate attempt to get a confession. Yezhov warned that Zinoviev must affirm at a public trial that he had plotted the assassination of Stalin and other members of the Politburo. Zinoviev declined the demand. Yezhov then relayed Stalin's offer; that if he co-operated at an open trial, his life would be spared; if he did not, he would be tried in a closed military court and executed, along with all of the opposition. Zinoviev vehemently rejected Stalin's offer. Yezhov then tried the same tactics on Kamenev and again was rebuffed."

In July 1936 Yezhov told Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev that their children would be charged with being part of the conspiracy and would face execution if found guilty. The two men now agreed to co-operate at the trial if Joseph Stalinpromised to spare their lives. At a meeting with Stalin, Kamenev told him that they would agree to co-operate on the condition that none of the old-line Bolsheviks who were considered the opposition and charged at the new trial would be executed, that their families would not be persecuted, and that in the future none of the former members of the opposition would be subjected to the death penalty. Stalin replied: "That goes without saying!"

The trial opened on 19th August 1936. Five of the sixteen defendants were actually NKVD plants, whose confessional testimony was expected to solidify the state's case by exposing Zinoviev, Kamenev and the other defendants as their fellow conspirators. The presiding judge was Vasily Ulrikh, a member of the secret police. The prosecutor was Andrei Vyshinsky, who was to become well-known during the Show Trials over the next few years.

Yuri Piatakov accepted the post of chief witness "with all my heart." Max Shachtman pointed out: "The official indictment charges a widespread assassination conspiracy, carried on these five years or more, directed against the head of the Communist party and the government, organized with the direct connivance of the Hitler regime, and aimed at the establishment of a Fascist dictatorship in Russia. And who are included in these stupefying charges, either as direct participants or, what would be no less reprehensible, as persons with knowledge of the conspiracy who failed to disclose it?"

The men made confessions of their guilt. Lev Kamenev said: "I Kamenev, together with Zinoviev and Trotsky, organised and guided this conspiracy. My motives? I had become convinced that the party's - Stalin's policy - was successful and victorious. We, the opposition, had banked on a split in the party; but this hope proved groundless. We could no longer count on any serious domestic difficulties to allow us to overthrow. Stalin's leadership we were actuated by boundless hatred and by lust of power."

Gregory Zinoviev also confessed: "I would like to repeat that I am fully and utterly guilty. I am guilty of having been the organizer, second only to Trotsky, of that block whose chosen task was the killing of Stalin. I was the principal organizer of Kirov's assassination. The party saw where we were going, and warned us; Stalin warned as scores of times; but we did not heed these warnings. We entered into an alliance with Trotsky."

Kamenev's final words in the trial concerned the plight of his children: "I should like to say a few words to my children. I have two children, one is an army pilot, the other a Young Pioneer. Whatever my sentence may be, I consider it just... Together with the people, follow where Stalin leads." This was a reference to the promise that Stalin made about his sons.

On 24th August, 1936, Vasily Ulrikh entered the courtroom and began reading the long and dull summation leading up to the verdict. Ulrikh announced that all sixteen defendants were sentenced to death by shooting. Edward P. Gazur has pointed out: "Those in attendance fully expected the customary addendum which was used in political trials that stipulated that the sentence was commuted by reason of a defendant's contribution to the Revolution. These words never came, and it was apparent that the death sentence was final when Ulrikh placed the summation on his desk and left the court-room." The following day Soviet newspapers carried the announcement that all sixteen defendants had been put to death.

Primary Sources

(1) The Granat Encyclopaedia of the Russian Revolution was published by the Soviet government in 1924. The encyclopaedia included a collection of autobiographies and biographies of over two hundred people involved in the Russian Revolution.

Zinoviev played a vigorous role in the Party electoral campaign for the third Duma, whilst at the same time being fully involved in the clandestine life of the Party. In spring 1908 he was arrested during an editorial meeting on the Vasilievsky Ostrov. The Okhrana, however, was not fully apprised of his activity. He fell seriously ill in custody and thanks to the intervention of the late D. V. Stasov, he was soon snatched from prison's grasp, being released under police supervision within a few months.

(2) Louis Fischer, Current History Magazine (June, 1925)

One is at a loss sometimes to explain the ascendancy of a man like Gregory Zinoviev.... His mental powers are mediocre, his personality far from being winning, even to his own party colleagues is often repulsive. With his high, monotonous falsetto voice he could not be an orator even if his speeches excelled in style, incision and depth, and this is not generally the case.

(3) Victor Serge, Year One of the Russian Revolution (1930)

Zinoviev, a collaborator of Lenin's since 1907, theoretician, popularizer and orator, is defending, at Petrograd, one of the most advanced and most threatened outposts of the Republic. As President of the Executive Committee of the Northern Commune, he is the dictator of a great workers's city, starving, cholera-stricken and vulnerable to surprise attack. Zinoviev, with his tousled head, smooth, rather flabby face, nonchalent stance, rounded gestures, deep, sometimes strident and always audible voice, Zinoviev, with his merciless choice of words often confronts and subdues, in the old capital's factories, the discontent and anger of a proletariat whose best sons are at the front, and which is dying of hunger.

(4) Gregory Zinoviev, speech at the Eleventh Party Congress (1922)

I am speaking concerning the fact that we constitute the single legal party in Russia: that we maintain a so-called monopoly on legality. We have taken away political freedom from our opponents; we do not permit the legal existence of those who strive to compete with us. We have clamped a lock on the lips of the Mensheviks and the Socialist Revolutionaries. We could not have acted otherwise. The dictatorship of the proletariat, Comrade Lenin says, is a very terrible undertaking. It is not possible to ensure the victory of the dictatorship of the proletariat without breaking the backbone of all opponents of the dictatorship. No one can appoint the time when we shall be able to revise our attitude to this question.

(5) The Granat Encyclopaedia of the Russian Revolution was first published by the Soviet government in 1924. Revised versions were published at regular intervals. The encyclopaedia included a collection of autobiographies and biographies of over two hundred people involved in the Russian Revolution. It included a biography of Leon Trotsky.

In 1924 a collection of Trotsky's articles appeared with a preface entitled 'The Lessons of October'. In it the whole Bolshevik concept of revolution underwent revision and the basis of the opposition platform became the hypothesis of permanent revolution, that is, Trotsky's fundamental error, his disparagement of the role of the peasantry in the revolution. This led to the formation of a Trotskyite party and a struggle with the Communist Central Committee. The latter could not reply to this in any other way than by expelling Trotsky and the opposition from its ranks.

(6) Robert V. Daniels, Red October: The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 (1967)

The man who served as Lenin's second-in-command from this time until the revolution was Grigori Zinoviev, born in 1883 to a middle-class Jewish family (whose real name was Radomyslsky) in western Russia. Curly-haired and clean shaven, contrary to the fashion, Zinoviev was inclined to panic and sometimes gave the impression of a slight effeminacy, though he had great powers of endurance both in oratory and conspiracy. Lenin is supposed to have complained, "He copies my faults," but trusted him both before and after the revolution as the kind of lieutenant who would handle any unsavory task without question. Zinoviev lived and worked with Lenin almost without interruption from 1907 until 1917, spent the war years with him in Switzerland, and rode with him on the train across Germany to get back to Russia in April, 1917. Probably no one knew Lenin better - and none among the Bolsheviks was a more determined opponent when Lenin called for insurrection.

(7) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1945)

Zinoviev, the President of the Soviet, by contrast affected an extraordinary confidence. Clean-shaven, pale, his face a little puffy, he felt absolutely at home on the pinnacle of power, being the most long-standing of Lenin's collaborators in the Central Committee: all the same there was also an impression of flabbiness, almost of a lurking irresolution, emanating from his whole personality. Abroad, a frightful reputation for terror surrounded his name.

(8) Walter Duranty, I Write As I Please (1935)

In August, 1925, I returned to Moscow and found the country in a state of bewildering confusion. I had been absent a full year, and although I had tried to keep in touch with Soviet affairs through the Moscow newspapers I soon saw that much had happened and was about to happen to which I had no clue. I felt lost, like a blind man groping. Thereupon I determined to test my new resolutions about thinking for myself and to see whether I could not turn my disadvantage into profit, as Bolitho had advised. The weakness of my position was that I had been too remote from the Soviet scene to gauge the meaning of events, but surely that gave me the advantage of detachment? Unable to distinguish separate trees I ought therefore to see the wood more clearly as a whole. And so, before running round to see people and get facts second-hand, I sat down to think things out for myself, and reached four major conclusions, which I have never had reason to change, as follows: -

1. That inside the Bolshevik Party there was a hard central core which had never wavered from the intention to create and develop a successful proletarian State upon Socialist foundations.

2. That the Party controversy did not affect this determination, but was concerned with three points: by whom, how, and at what speed the socialisation process should be conducted; and that all these points were of vital moment.

3. That N.E.P., it was now clear, was no more than a temporary measure, the ostensible purpose of which was to give the whole country a breathing space, but whose real purpose was to enable the Bolsheviks to build up enough industry and commerce, and store up enough reserve to enable them to tackle the work of building a Socialist State with greater success than in 1918-21.

4. That a new reckoning with the peasants was inevitable and not far distant.

Having reached these conclusions, I thought about them. My first conclusion was chiefly important as background; I must never lose sight of it for a moment, but it was henceforth to me too axiomatic - as it was too fundamental - to have much practical news value. My second conclusion, I thought, was the most important thing in my world from the point of news and everything else, because, until the problem it presented was solved no other problems could be solved. NEP I thought was doomed, at least as far as urban private traders were concerned, and all the rest of the private enterprises which had danced like grasshoppers in the sun during the past four years. NEP, therefore, had a diminishing value, both politically and as news. Finally, the peasant question was not, I could see, yet acute, but, I told myself, I must keep it also in mind as a big future issue and more immediately as a key pawn in the merciless chess game that was being played between Stalin and Trotsky. Continuing my thought, I concluded that there was no reason for me to change my opinion that Stalin would beat Trotsky in the long run - had not the latter been removed from the Commissariat of War a few months earlier and replaced by Frunze - although I had read and admired Trotsky's pamphlet called The Lessons of October which he had published in the previous autumn. It was a strong and subtle piece of work, which the Stalinists not only found it difficult to answer but which later disintegrated their forces considerably.

In this pamphlet Trotsky called for a return to the fundamental principles of Marxism, of which he said the Bolsheviks were losing sight. His main thesis was that the Revolution must be dynamic, not static, that it could not mark time but must always, everywhere, push forward. Trotsky utilised this theoretically sound Marxist basis for a telling attack upon the home and foreign policies of the Stalinists and more particularly upon the theory, which they had not yet fully adopted, although it was in process of formation, that it was possible to "build Socialism in a single country". This theory, be it said, Marx had once described as rank heresy, although Stalin's apologists later argued with evident justice that in speaking of "a country" Marx had in mind the comparatively small States of Europe rather than such vast and economically self-sufficient continental units as the United States and the USSR. Trotsky thus appealed to Marxist internationalism and the ideal of World Revolution against Stalin's policy as ruler of Russia; he was trying to drive a wedge between the Bolshevik as Bolshevik, that is Marxist revolutionary, and the Bolshevik as statesman directing the destinies of a nation. To this apple of discord flung into the midst of his victorious opponents in the Central Committee, Trotsky added a grain of mustard seed, which later grew and flourished exceedingly, in the shape of a question about class differentiation in the villages and the right course to be adopted towards the kulaks and middle peasants.

I thought about the pamphlet for a long time, and the more I thought the more I felt sure that the Party controversy was big news. The next day I went out to gather information. I have found since that there are two dangers in the practice of "doping things out" for yourself; first, you are liable to twist facts to suit your conclusion; secondly, if your conclusion is erroneous the deductions you draw from it are more erroneous still. In this case, however, it seemed that I had guessed right, especially about the Party squabble. I heard that the Kamenev-Zinoviev group in the Stalin bloc were showing signs of restiveness, partly because they saw that Stalinism was progressing from Leninism (as Leninism had progressed from Marxism) towards a form and development of its own, partly because they were jealous and alarmed by Stalin's growing predominance. All my informants agreed that the Party fight would be the news centre for the coming winter.

Sure enough, as events proved, Zinoviev and Kamenev spent the autumn in creating inside the majority bloc a new opposition movement and, what is more, they concealed their doings so dexterously that it was not until the delegates to the December Party Congress had been elected that Stalin perceived how the wind was blowing. Kamenev's case was relatively unimportant; he had a fair measure of support in the Moscow delegation but nothing like a majority. Zinoviev, however, had long been undisputed boss of Leningrad and had packed the delegation from top to bottom with his own henchmen. It was too late to change the delegations, but the Party Secretariat (i.e. Stalin) lost not a moment in cutting the ground from under Zinoviev's feet. There was a radical change in personnel amongst the permanent officials of the Leningrad Party machine, particularly in the Communist Youth organisation, where pro-Zinoviev tendencies were most marked. The editorial staff of the two Party organs, the Leningrad Pravda and the Leningrad Communist Youth Pravda, were sweepingly reformed; and a vigorous "educational campaign' (i.e. propaganda drive) was begun in every factory and office in the city. These measures were decided at a secret meeting of the Central Committee of the Party in November and embodied in a resolution of twenty-four points, carried, but with half a dozen significant abstentions. At this point I myself, inadvertently, came into the game. Among the newspapers I read daily was a little sheet in tabloid form called The Workers' Gazette. One morning I was startled to find on its back page, unheralded by headlines, the report of a Central Committee resolution in twenty-four paragraphs "concerning the administrative organisation of the Leningrad Party and Communist Youth organisation". It was strongly worded; phrases like "grave ideological errors," "weakness of discipline and Party control", "failure of the Party executives to appreciate correctly", and so forth were followed by the blunt announcement that the Leningrad Party machine and Press would be reorganised; individuals "dismissed with blame" were named and their successors appointed. This document, I understood, was a direct frontal attack upon Zinoviev and the administration of the Leningrad Party; which could only mean that Zinoviev and his chief colleagues in the Leningrad Party who had been Stalin's strongest supporters against Trotsky, were now themselves in Opposition. This was interesting news, although of course I did not dream that it was the first step towards the formation of the bloc of all opposition movements, however mutually disparate, which developed in the following year. That I could not guess, but I did know, to my regret, that the "somewhat Byzantine squabbles of the Bolsheviks", as a New York Times editorial had cuttingly described them, were of little greater interest to the mass of my readers than the Arian heresy which convulsed the early Christian Church.

(9) Leon Trotsky, Zinoviev and Kamenev (December, 1936)

Zinoviev and Kamenev are two profoundly different types. Zinoviev is an agitator. Kamenev a propagandist. Zinoviev was guided in the main by a subtle political instinct. Kamenev was given to reasoning and analyzing. Zinoviev was always inclined to fly off at a tangent. Kamenev, on the contrary, erred on the side of excessive caution. Zinoviev was entirely absorbed by politics, cultivating no other interests and appetites. In Kamenev there sat a sybarite and a aesthete. Zinoviev was vindictive. Kamenev was good nature personified.

I do not know what their mutual relations were in emigration. In 1917 they were brought close together for a time by their opposition to the October revolution. In the first few years after the victory, Kamenev's attitude toward Zinoviev was rather ironical. They were subsequently drawn together by their opposition to me, and later, to Stalin. Throughout the last thirteen years of their lives, they marched side by side and their names were always mentioned together.

With all their individual differences, outside of their common schooling gained by them in emigration under Lenin's guidance, they were endowed with almost an identical range of intellect and will. Kamenev's analytical capacity served to compliment Zinoviev's instinct; and they would jointly explore for a common decision. Both of them were deeply and unreservedly devoted to the cause of socialism. Such is the explanation for their tragic union.

(10) Gregory Zinoviev, speech at his trial (August, 1936)

I would like to repeat that I am fully and utterly guilty. I am guilty of having been the organizer, second only to Trotsky, of that block whose chosen task was the killing of Stalin. I was the principal organizer of Kirov's assassination. The party saw where we were going, and warned us; Stalin warned as scores of times; but we did not heed these warnings. We entered into an alliance with Trotsky.

(11) The Observer (23rd August, 1936)

It is futile to think the trial was staged and the charges trumped up. The government's case against the defendants (Zinoviev and Kamenev) is genuine.

(12) The New Republic (2nd September, 1936)

Some commentators, writing at a long distance from the scene, profess doubt that the executed men (Zinoviev and Kamenev) were guilty. It is suggested that they may have participated in a piece of stage play for the sake of friends or members of their families, held by the Soviet government as hostages and to be set free in exchange for this sacrifice. We see no reason to accept any of these laboured hypotheses, or to take the trial in other than its face value. Foreign correspondents present at the trial pointed out that the stories of these sixteen defendants, covering a series of complicated happenings over nearly five years, corroborated each other to an extent that would be quite impossible if they were not substantially true. The defendants gave no evidence of having been coached, parroting confessions painfully memorized in advance, or of being under any sort of duress.

(13) The New Statesman (5th September, 1936)

Very likely there was a plot. We complain because, in the absence of independent witnesses, there is no way of knowing. It is their (Zinoviev and Kamenev) confession and decision to demand the death sentence for themselves that constitutes the mystery. If they had a hope of acquittal, why confess? If they were guilty of trying to murder Stalin and knew they would be shot in any case, why cringe and crawl instead of defiantly justifying their plot on revolutionary grounds? We would be glad to hear the explanation.

(14) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1945)

And on 14 August, like a thunderbolt, came the announcement of the Trial of the Sixteen, concluded on the 25th - eleven days later - by the execution of Zinoviev, Kamenev, Ivan Smirnov, and all their fellow-defendants. I understood, and wrote at once, that this marked the beginning of the extermination of all the old revolutionary generation. It was impossible to murder only some, and allow the others to live, their brothers, impotent witnesses maybe, but witnesses who understood what was going on.

(15) Leon Trotsky, interviewed by St. Louis Post-Dispatch (17th January, 1937)

The Western attorneys of the GPU represent the confessions of Zinoviev and the others as spontaneous expressions of their sincere repentance. This is the most shameless deception of public opinion that can be imagined. For almost 10 years, Zinoviev, Kamenev and the others found themselves under almost insupportable moral pressure with the menace of death approaching ever closer and closer. If an inquisitor judge were to put questions to this victim and inspire the answers, his success would be guaranteed in advance. Human nerves, even the strongest, have a limited capacity to endure moral torture.

(16) Robin Page Arnot, The Labour Monthly (November 1937)

In December 1934 one of the groups carried through the assassination of Sergei Mironovich Kirov, a member of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Subsequent investigations revealed that behind the first group of assassins was a second group, an Organisation of Trotskyists headed by Zinoviev and Kamenev. Further investigations brought to light definite counter-revolutionary activities of the Rights (Bucharin-Rykov organisations) and their joint working with the Trotskyists. The group of fourteen constituting the Trotskyite-Zinovievite Terrorist Centre were brought to trial in Moscow in August 1936, found guilty, and executed. In Siberia a trial, held in November, revealed that the Kemerovo mine had been deliberately wrecked and a number of miners killed by a subordinate group of wreckers and terrorists. A second Moscow trial, held in January 1937, revealed the wider ramifications of the conspiracy. This was the trial of the Parallel Centre, headed by Pyatakov, Radek, Sokolnikov, Serebriakov. The volume of evidence brought forward at this trial was sufficient to convince the most sceptical that these men, in conjunction with Trotsky and with the Fascist Powers, had carried through a series of abominable crimes involving loss of life and wreckage on a very considerable scale. With the exceptions of Radek, Sokolnikov, and two others, to whom lighter sentences were given, these spies and traitors suffered the death penalty. The same fate was meted out to Tukhachevsky, and seven other general officers who were tried in June on a charge of treason. In the case of Trotsky the trials showed that opposition to the line of Lenin for fifteen years outside the Bolshevik Party, plus opposition to the line of Lenin inside the Bolshevik Party for ten years, had in the last decade reached its finality in the camp of counter-revolution, as ally and tool of Fascism.