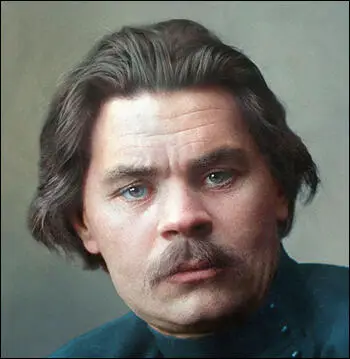

Maxim Gorky

Alexander Peshkov (later known as Maxim Gorky was born in Nizhny Novgorod on 28th March, 1868. His father was a shipping agent but he died when Gorky was only five years old. His mother remarried and Gorky was brought up by his grandmother.

Gorky left home in 1879 and went to live in a small village in Kazan and worked as a baker. At this time radical groups such as the Land and Liberty group sent people into rural areas to educate the peasants. Gorky attended these meetings and it was during this period that Gorky read the works of Nikolai Chernyshevsky, Peter Lavrov , Alexander Herzen, Karl Marx and George Plekhanov. Gorky became a Marxist but he was later to say that was largely because of the teachings of the village baker, Vasilii Semenov.

In 1887 Gorky witnessed a Pogrom in Nizhny Novgorod. Deeply shocked by what he saw, Gorky became a life-long opponent of racism. Gorky worked with the Liberation of Labour group and in October, 1889 was arrested and accused of spreading revolutionary propaganda. He was later released because they did not have enough evidence to gain a conviction. However, the Okhrana decided to keep him under police surveillance.

Osip Volzhanin met Gorky in 1889: "He was tall, stooped, dressed in a coat-like jacket and high polished boots. His face was ordinary, plebeian, with a homely duck-like nose. By his appearance he could easily have been taken for a worker or a craftsman. The young man sat on the window sill, and swinging his long legs, spoke strongly emphasizing the letter 'O'. We listened with great delight to his stories, though Somov, an implacable 'political', disapproved of the stories and the behaviour of the young man. In his opinion, the latter occupied himself with trifles."

In 1891 Gorky moved to Tiflis where he found employment as a painter in a railway yard. The following year his first short-story, Makar Chudra, appeared in the Tiflis newspaper, Kavkaz. He story appeared under the name Maxim Gorky (Maxim the Bitter). The story was popular with the readers and soon others began appearing in other journals such as the successful Russian Wealth.

Gorky also began writing articles on politics and literature for newspapers. In 1895 he began writing a daily column under the heading, By the Way. In this articles he campaigned against the eviction of peasants from their land and the persecution of trade unionists in Russia. He also criticized the country's poor educational standards, the government's treatment of the Jewish community and the growth in foreign investment in Russia.

In his story Twenty-six Men and a Girl, one of his characters comment: “The poor are always rich in children, and in the dirt and ditches of this street there are groups of them from morning to night, hungry, naked and dirty. Children are the living flowers of the earth, but these had the appearance of flowers that have faded prematurely, because they grew in ground where there was no healthy nourishment.”

Gorky's short stories often showed Gorky's interest in social reform. In a letter to a friend, Gorky argued that "the aim of literature is to help man to understand himself, to strengthen the trust in himself, and to develop in him the striving toward truth; it is to fight meanness in people, to learn how to find the good in them, to awake in their souls shame, anger, courage; to do all in order that man should become nobly strong."

In 1898 Gorky published his first collection of short-stories. The book was a great success and he was now one of the country's most read and discussed writers. His choice of heroes and themes helped him emerge as the champion of the poor and the oppressed. The Okhrana became greatly concerned with Gorky's outspoken views, especially his articles and stories about the police, but his increasing popularity with the public made it difficult for them to take action against him.

Gorky secretly began helping illegal organizations such as the Socialist Revolutionaries and the Social Democratic Labour Party. He donated money to party funds and helped with the distribution of radical newspapers such as Iskra. One Bolsheviks later recalled that Gorky's contribution included "financial help systematically paid every month, technical assistance in the establishment of printing shops, organizing transport of illegal literature, arranging for meeting places, and supplying addresses of people who could be helpful."

On 4th March, 1901, Gorky witnessed a police attack on a student demonstration in Kazan. After publishing a statement attacking the way the police treated the demonstrators, Gorky was arrested and imprisoned. Gorky's health deteriorated and afraid he would die, the authorities released him after a month. He was put under house arrest, his correspondence was monitored and restrictions were placed on his movement around the country. When he was allowed to travel to the Crimea, he was greeted on the route by large crowds bearing banners with the words: "Long live Gorky, the bard of Freedom exiled without investigation or trial."

In 1902 Gorky was elected to the Imperial Academy of Literature. Nicholas II was furious when he heard the news and wrote to his Minister of Education: "Neither Gorky's age nor his works provide enough ground to warrant his election to such an honorary title. Much more serious is the circumstance that he is under police surveillance. And the Academy is allowing, in our troubled times, such a person to be elected! I am deeply dismayed by all this and entrust to you to announce that on my orders, the election of Gorky is to be cancelled."

When news that the Academy had followed the Tsar's orders and had overruled Gorky's election, several writers resigned in protest. Later that year the statutes of the Academy were changed, giving Nicholas II the power to approve the list of candidates before they came up for election.

Gorky gave his support to Father George Gapon and his planned march to the Winter Palace. He attended the march on the 22nd January, 1905, and that night Gapon stayed in his house. After Blood Sunday Gorky changed his mind about the moral right for revolutionaries to use violence. He wrote to a friend: "Two hundred black eyes will not paint Russian history over in a brighter colour; for that, blood is needed, much blood. Life has been built on cruelty and force. For its reconstruction, it demands cold calculated cruelty - that is all! They kill? It is necessary to do so! Otherwise what will you do? Will you go to Count Tolstoy and wait with him?"

After Blood Sunday Gorky was arrested and charged with inciting the people to revolt. Following a wide-world protest at Gorky's imprisonment in the Peter and Paul Fortress, Nicholas II agreed for him to be deported from Russia. Gorky now spent his time attempting to gain support for the overthrow of the Russian autocracy. This included raising money to buy arms for the Socialist Revolutionaries and the Social Democratic Labour Party. He also helped to fund the new Bolsheviks newspaper Novaya Zhizn.

In 1906 Gorky toured Europe and the United States. He arrived in New York on 28th March, 1906 and the New York Times reported that "the reception given to Gorky revealed with that of Kossuth and Garibaldi." His campaign tour was organized by a group of writers that included Ernest Poole, William Dean Howells, Jack London, Mark Twain, Charles Beard and Upton Sinclair.

The New York World newspaper decided to run a smear campaign against Gorky. The American public were shocked to hear that Gorky was staying in his hotel with a woman who was not his wife. The newspaper printed that the "so-called Mme Gorky who is not Mme Gorky at all, but a Russian actress Andreeva, with whom he has been living since his separation from his wife a few years ago." As a result of the story Gorky was evicted from his hotel and William Dean Howells and Mark Twain changed their mind about supporting his campaign. President Theodore Roosevelt also withdrew his invitation for Gorky to meet him in the White House.

Others such as H. G. Wells continued to help Gorky and issued a statement that included the comment: "I do not know what motive actuated a certain section of the American press to initiate the pelting of Maxim Gorky. A passion for moral purity ever before begot so brazen and abundant torrent of lies." Frank Giddings, a sociologist, compared the attack on Gorky to the lynching of three African Americans in Missouri. "Maxim Gorky came to this country not for the purpose of putting himself on exhibition, as many literary characters have done at one time or another, not for the purpose of lining his pockets with American gold, but for the purpose of obtaining sympathy and financial assistance for a people struggling against terrific odds, as the American people once struggled, for political and individual liberty. All was assertion, accusation, hysteria, impertinence in the way the papers have tried to instruct Gorky in morality."

Gorky also upset other supporters by sending a telegram of support to William Haywood, the leader of the Industrial Workers of the World, who was in prison waiting to be tried for the murder of the politician, Frank Steunenberg. Later Gorky published a book American Sketches, where he criticized the gross inequalities in American society. In one article he wrote that if anyone "wanted to become a socialist in a hurry, he should come to the United States."

In 1907 Gorky attended the Fifth Congress of the Social Democratic Labour Party. While there he met Lenin, Julius Martov, George Plekhanov, Leon Trotsky and other leaders of the party. Gorky preferred Martov and the Mensheviks and was highly critical of Lenin's attempts to create a small party of professional revolutionaries. Gorky commented that he was not impressed with Lenin: "I did not expect Lenin to be like that. Something was lacking in him. He rolled his r's gutturally, and had a jaunty way of standing with his hands somehow poked up under his armpits. He was somehow too ordinary and did not give the impression of being a leader."

Gorky was later to write about Lenin: "Squat and solid, with a skull like Socrates and the all-seeing eyes of a great deceiver, he often liked to assume a strange and somewhat ludicrous posture: throw his head backwards, then incline it to the shoulder, put his hands under his armpits, behind the vest. There was in this posture something delightfully comical, something triumphantly cocky. At such moments his whole being radiated happiness. His movements were lithe and supple and his sparing but forceful gestures harmonized well with his words, also sparing but abounding in significance. From his face of Mongolian cast gleamed and flashed the eyes of a tireless hunter of falsehood and of the woes of life - eyes that squinted, blinked, sparkled sardonically, or glowered with rage. The glare of those eyes rendered his words more burning and more poignantly clear.... A passion for gambling was part of Lenin's character. But this was not the gambling of a self-centred fortune seeker. In Lenin it expressed that extraordinary power of faith which is found in a man firmly believing in his calling, one who is deeply and fully conscious of his bond with the world outside and has thoroughly understood his role in the chaos of the world, the role of an enemy of chaos."

Gorky continued to write and his most successful novels include Three of Them (1900), Mother (1906), A Confession (1908), Okurov City (1909) and the Life of Matvey Kozhemyakin (1910). Gorky argued: "The aim of literature is to help man to understand himself, to strengthen the trust in himself, and to develop in him the striving toward truth; it is to fight meanness in people, to learn how to find the good in them, to awake in their souls shame, anger, courage; to do all in order that man should become nobly strong."

Gorky was strongly opposed the First World War and he was attacked in the Russian press as being unpatriotic. In 1915 he established the political-literary journal, Letopis (Chronicle) and helped establish the Russian Society of the Life of the Jews, an organization that protested against the persecution of the Jewish community in Russia.

In March, 1917, Gorky welcomed the abdication of Nicholas II and supported the Provisional Government. Gorky wrote to his son: "We won not because we are strong, but because the government was weak. We have made a political revolution and have to reinforce our conquest. I am a social democrat, but I am saying and will continue to say, that the time has not come for socialist-style reforms."

With the support of the Mensheviks, Gorky started a newspaper, New Life, in 1917, and used it to attack the idea that the Bolsheviks were planning to overthrow the government of Alexander Kerensky. On 16th October, 1917, he called on Lenin to deny these rumours and show he was "capable of leading the masses, and not a weapon in the hands of shameless adventurers of fanatics gone mad."

After the October Revolution the new government got Joseph Stalin to lead the attack on Gorky. In the newspaper Workers' Road, Stalin wrote: "A whole list of such great names was discarded by the Russian Revolution. Plekhanov, Kropotkin, Breshkovskaia, Zasulich and all those revolutionaries who are distinguished only because they are old. We fear that Gorky is drawn towards them, into the archives. Well, to each his own. The Revolution neither pities nor buries its dead."

Gorky retaliated by writing in the New Life in 7th November, 1917. "Lenin and Trotsky and their followers already have been poisoned by the rotten venom of power. The proof of this is their attitude toward freedom of speech and of person and toward all the ideals for which democracy was fighting." Three days later Gorky called Lenin and Leon Trotsky the "Napoleons of socialism" who were involved in a "cruel experiment with the Russian people."

Victor Serge met Gorky during this period: "His apartment at the Kronversky Prospect, full of books, seemed as warm as a greenhouse. He himself was chilly even under his thick grey sweater, and coughed terribly, the result of his thirty years' struggle against tuberculosis. Tall, lean and bony, broad-shouldered and hollow-chested, he stooped a little as he walked. His frame, sturdily-built but anaemic, appeared essentially as a support for his head. An ordinary, Russian man in the street's head, bony and pitted, really almost ugly with its jutting cheek-bones, great thin-lipped mouth and professional smeller's nose, broad and peaked."

In January, 1918, Gorky led the attack on Lenin's decision to close down the Constituent Assembly. Gorky wrote in the New Life that the Bolsheviks had betrayed the ideals of generations of reformers: "For a hundred years the best people of Russia lived with the hope of a Constituent Assembly. In this struggle for this idea thousands of the intelligentsia perished along with tens of thousands of workers and peasants."

The Bolshevik government controlled the distribution of newsprint and in July, 1918, it cut off supplies to New Life and Gorky was forced to close his newspaper. The government also took action making it impossible for Gorky to get his work published in Russia.

During the Civil War Gorky agreed to give his support to the Bolsheviks against the White Army. In return Lenin gave him permission to establish the publishing company, World Literature. This enabled Gorky to give employment to people such as Victor Serge and other critics of the Soviet government. Privately, Gorky remained an opponent of the government. In September, 1919, he wrote to Lenin: "for me it became clear that the "reds" are the enemies of the people just as the "whites". Personally, I of course would rather be destroyed by the "whites", but the "reds" are also no comrades of mine."

In 1921 Gorky once again clashed with the Soviet government over the suppression of the Kronstadt Uprising. Gorky blamed Gregory Zinoviev for the way the sailors were treated after the rebellion. Gorky failed to save the life of the writer, Nikolai Gumilev, who was arrested and executed for his support for the Kronstadt sailors. He was also unsuccessfully in obtaining an exit visa for the poet, Alexander Blok, who was dangerously ill. By the time Zinoviev gave permission for Blok to leave the country, he was dead.

Gorky based his play, The Plodder Slovotekov, on his experiences of dealing with Gregory Zinoviev. The play began its run on 18th June, 1921, but its criticism of the Soviet government's inefficient bureaucracy resulted in it being closed down after only three performances.

During the terrible famine of 1921, Gorky used his world fame to appeal for funds to provide food for the people starving in Russia. One of those who responded was Herbert Hoover, head of the American Relief Administration (ARA).

Gorky continued to criticize the Soviet government and after coming under considerable pressure from Lenin, he agreed to leave the country. In October, 1921, Gorky went to live in Germany where he joined a community of around 600,000 Russian émigrés. He continued to criticize Lenin and in one article wrote: "Russia is not of any concern to Lenin but as a charred log to set the bourgeois world on fire."

In July, 1922, Gorky campaigned against the decision to sentence to death twelve leading members of the Socialist Revolutionary Party. He wrote to Alexei Rykov: "If the trial of the Socialist Revolutionaries will end with a death sentence, then this will be a premeditated murder, a foul murder. I beg of you to inform Leon Trotsky and the others that this is my contention. I hope this will not surprise you since I had told the Soviet authorities a thousand times that it is a senseless and criminal to decimate the ranks of our intelligentsia in our illiterate and lacking of culture country. I am convinced, that if the SR's should be executed the crime will result in a moral blockade of Russia by all of socialist Europe."

Gorky stayed in Germany for two and half years before moving to Sorrento in Italy. He continued to take a keen interest in Russian literature and was particularly impressed with the work of Isaac Babel, Vsevolod Ivanov and Konstantin Fedin. He often invited these writers to stay with him in Sorrento and did what he could to promote their careers.

Joseph Stalin attempted to bring an end to Gorky's exile by inviting him back to his homeland to celebrate the author's sixtieth birthday. Gorky accepted the invitation and returned on 20th May, 1928. Stalin wanted Gorky to write a biography of him. He refused but did take the opportunity to seek help for those writers being persecuted in the Soviet Union. This included asking for exit visas for some writers and the publication of the works of others.

Over the next few years Gorky played an important role in saving the lives of writers such as Victor Serge and Yevgeni Zamyatin when he successfully obtained permission from Stalin to let them leave the Soviet Union. In return, Gorky agreed to publicly support some of Stalin's policies. This included collectivization, his opposition to world revolution, and the formation of the Soviet Writers' Union. It is unlikely that Gorky ever discovered the full picture of what Stalin was doing in the Soviet Union. He was kept under close surveillance by the NKVD and his private correspondence reveals that he believed Stalin that Leon Trotsky and his followers were behind the assassination of Sergy Kirov.

Ella Winter saw Gorky lecture on literature to students during a visit in 1932: "He (Gorky) was like a stringy poplar tree, tall and thin and frail, his face, with its big walrus mustache, paper yellow like old parchment. He looked as if he might topple over. But he talked for an hour, about writing and literary problems, and held his audience; some inner strength seemed to support him."

Maxim Gorky died of a heart attack on 18th June, 1936. Rumours began circulating that Stalin had arranged for him to be murdered. This story was given some support when Genrikh Yagoda, the head of the NKVD at the time of his death, was successfully convicted of Gorky's murder in 1938.

Primary Sources

(1) Osip Volzhanin first met Maxim Gorky in 1889.

He was tall, stooped, dressed in a coat-like jacket and high polished boots. His face was ordinary, plebeian, with a homely duck-like nose. By his appearance he could easily have been taken for a worker or a craftsman. The young man sat on the window sill, and swinging his long legs, spoke strongly emphasizing the letter "O". We listened with great delight to his stories, though Somov, an implacable "political", disapproved of the stories and the behaviour of the young man. In his opinion, the latter occupied himself with trifles.

(2) Statement signed by Maxim Gorky and forty-two other people who were critical of the way the police dealt with the student demonstration on 4th March, 1901.

We believe that the students were provoked by the police to assemble, and that the leaflets and the invitations issued to the students originated in the offices of the Okhrana. We declare that the Cossacks and not the students were first to start the scuffle, that the Cossacks grabbed women by their hair and beat them with whips.

(3) Maxim Gorky, letter to N. D. Teleshov (December, 1901)

The aim of literature is to help man to understand himself, to strengthen the trust in himself, and to develop in him the striving toward truth; it is to fight meanness in people, to learn how to find the good in them, to awake in their souls shame, anger, courage; to do all in order that man should become nobly strong.

(4) Maxim Gorky was one of those who took part in the march to the Winter Palace on 22nd January, 1915. That night George Gapon took refuge in Gorky's house.

Gapon by some miracle remained alive, he is in my house asleep. He now says there is no Tsar anymore, no church, no God. This is a man who has great influence upon the workers of the Putilov works. He has the following of close to 10,000 men who believe in him as a saint. He will lead the workers on the true path.

(5) Maxim Gorky wrote to Leonid Andreev about his first impressions of New York (11th April, 1906)

It is such an amazing fantasy of stone, glass, and iron, a fantasy constructed by crazy giants, monsters longing after beauty, stormy souls full of wild energy. All these Berlins, Parises, and other "big" cities are trifles in comparison with New York. Socialism should first be realized here - that is the first thing you think of, when you see the amazing houses, machines, etc.

(6) Frank Giddings, The Social Lynching of Gorky and Andreeva (1906)

Maxim Gorky came to this country not for the purpose of putting himself on exhibition, as many literary characters have done at one time or another, not for the purpose of lining his pockets with American gold, but for the purpose of obtaining sympathy and financial assistance for a people struggling against terrific odds, as the American people once struggled, for political and individual liberty. All was assertion, accusation, hysteria, impertinence in the way the papers have tried to instruct Gorky in morality.

(7) Maxim Gorky first met Vladimir Lenin at the Fifth Congress of the Social Democratic Labour Party in 1907.

When we were introduced, he shook me heartily by the hand, and scrutinizing me with his keen eyes and speaking in the tone of an old acquaintance, he said jocularly: "So glad you've come, believe you're fond of a scrap? There's going to be a fine old scuffle here."

I did not expect Lenin to be like that. Something was lacking in him. He rolled his r's gutturally, and had a jaunty way of standing with his hands somehow poked up under his armpits. He was somehow too ordinary and did not give the impression of being a leader.

(8) V. M. Khodasevich first met Maxim Gorky in 1916.

Before me stood a tall man of slender build, his head relative to his height, rather small. I was stuck by the intense, very attractive, childlike, blue eyes. There was nothing artificial about him, a simple demeanour, nothing that would harken of him being famous. He was dressed in a grey well-fitting suit, a blue shirt and no tie.

(9) Maxim Gorky, letter to his son (April, 1917)

Remember, the revolution just began, it will last for a long time. We won not because we are strong, but because the government was weak. We have made a political revolution and have to reinforce our conquest. I am a social democrat, but I am saying and will continue to say, that the time has not come for socialist-style reforms. The new government has inherited not a state but its ruins.

(10) Maxim Gorky, New Life (7th November, 1917)

Lenin and Trotsky and their followers already have been poisoned by the rotten venom of power. The proof of this is their attitude toward freedom of speech and of person and toward all the ideals for which democracy was fighting. Blind fanatics and conscienceless adventurers are rushing at full speed on the road on the road to a social revolution - in actuality, it is a road toward anarchy.

(11) Maxim Gorky, New Life (10th November, 1917)

Lenin and Trotsky and all who follow them are dishonoring the Revolution, and the working-class. Imagining themselves Napoleons of socialism. The proletariat is for Lenin the same as iron ore is for a metallurgist. It is possible, taking into consideration the present conditions, to cast out of this ore a socialist state? Obviously this is impossible. Conscious workers who follow Lenin must understand that a pitiless experiment is being carried out with the Russian people which is going to destroy the best forces of the workers, and which will stop the normal growth of the Russian Revolution for a long time.

(12) Maxim Gorky, New Life (9th January, 1918)

For a hundred years the best people of Russia lived with the hope of a Constituent Assembly. In this struggle for this idea thousands of the intelligentsia perished and tens of thousands of workers and peasants.

On 5th January, the unarmed revolutionary democracy of Petersburg - workers, officials - were peacefully demonstrating in favour of the Constituent Assembly. Pravda lies when it writes that the demonstration was organized by the bourgeoisie and by the bankers. Pravda lies; it knows that the bourgeoisie has nothing to rejoice in the opening of the Constituent Assembly, for they are of no consequence among the 246 socialists and 140 Bolsheviks. Pravda knows that the workers of the Obukhavo, Patronnyi and other factories were taking part in the demonstrations. And these workers were fired upon. And Pravda may lie as much as it wants, but it cannot hide the shameful facts.

(13) Maxim Gorky, letter to Alexei Rykov (3rd July, 1922)

If the trial of the Socialist Revolutionaries will end with a death sentence, then this will be a premeditated murder, a foul murder. I beg of you to inform Leon Trotsky and the others that this is my contention. I hope this will not surprise you since I had told the Soviet authorities a thousand times that it is a senseless and criminal to decimate the ranks of our intelligentsia in our illiterate and lacking of culture country. I am convinced, that if the SR's should be executed the crime will result in a moral blockade of Russia by all of socialist Europe.

(14) Maxim Gorky, Lenin (1924)

A passion for gambling was part of Lenin's character. But this was not the gambling of a self-centred fortune seeker. In Lenin it expressed that extraordinary power of faith which is found in a man firmly believing in his calling, one who is deeply and fully conscious of his bond with the world outside and has thoroughly understood his role in the chaos of the world, the role of an enemy of chaos.

He could with equal enthusiasm play chess, study a volume on the History of Dress, debate for hours with his comrades, fish, walk along the stony paths of Capri, hot and glowing in the southern sun, admire the golden colours of the furze bush and the dirty children of the fishermen...

He enjoyed fun, and when he laughed, his whole body shook, really bursting with laughter, sometimes until tears came into his eyes. There was an endless scale of shade and meaning in his inarticulate "Urn" - ranging from bitter sarcasm to cautious doubt, and there was often in it the keen humour given only to one who sees far ahead and knows well the satanic absurdities of life.

Squat and solid, with a skull like Socrates and the all-seeing eyes of a great deceiver, he often liked to assume a strange and somewhat ludicrous posture: throw his head backwards, then incline it to the shoulder, put his hands under his armpits, behind the vest. There was in this posture something delightfully comical, something triumphantly cocky. At such moments his whole being radiated happiness.

His movements were lithe and supple and his sparing but forceful gestures harmonized well with his words, also sparing but abounding in significance. From his face of Mongolian cast gleamed and flashed the eyes of a tireless hunter of falsehood and of the woes of life - eyes that squinted, blinked, sparkled sardonically, or glowered with rage. The glare of those eyes rendered his words more burning and more poignantly clear.

(15) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1945)

Maxim Gorky welcomed me affectionately. In the famished years of his youth, he had been acquainted with my mother's family at Nizhni-Novgorod. His apartment at the Kronversky Prospect, full of books, seemed as warm as a greenhouse. He himself was chilly even under his thick grey sweater, and coughed terribly, the result of his thirty years' struggle against tuberculosis. Tall, lean and bony, broad-shouldered and hollow-chested, he stooped a little as he walked. His frame, sturdily-built but anaemic, appeared essentially as a support for his head. An ordinary, Russian man in the street's head, bony and pitted, really almost ugly with its jutting cheek-bones, great thin-lipped mouth and professional smeller's nose, broad and peaked.

He spoke harshly about the Bolsheviks: they were "drunk with authority", "cramping the violent, spontaneous anarchy of the Russian people", and "starting bloody despotism all over again"; all the same they were "facing chaos alone" with some incorruptible men in their leadership. His observations always started from facts, from chilling anecdotes upon which he would base his well-considered generalizations.