Russia and the First World War

Although Tsar Nicholas II described himself as a man of peace, he favoured an expanded Russian Empire. Encouraged by Vyacheslav Plehve, the Minister of the Interior, the Tsar made plans to seize Constantinople and expanded into Manchuria and Korea.

On 8th February, 1904, the Japanese Navy launched a surprise attack on the Russian fleet at Port Arthur, therefore beginning the Russo-Japanese War. The Russian Navy fought two major battles to try and relieve Port Arthur but the Russians were defeated and were forced to withdraw. In May, 1905, the Russian Navy was attacked at Tsushima. Twenty Russian ships were sunk and another five were captured. Only four Russian ships managed to reach safety at Vladivostok. (1)

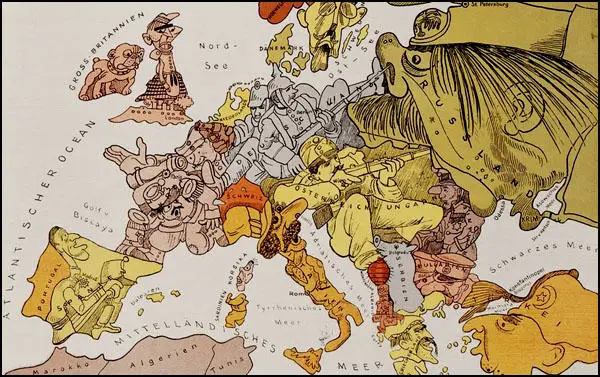

Sergi Witte led the Russian delegation at the peace conference held in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in August, 1905. Under the terms of the Treaty of Portsmouth: (i) The Liaotung Peninsula and the South Manchurian Railway went to Japan; (ii) Russia recognized Korea as a Japanese sphere of influence; (iii) The island of Sakhalin was divided into two; (iv) The Northern Manchuria and the Chinese Eastern Railway remained under Russian control. (2) At this time Russia and Austria-Hungary were in dispute over the area of south-eastern Europe known as the Balkans. Russia had formed a particularly close relationship with one of these nations, Serbia. This concerned Austria as there was a large Serb population within the Empire, and they feared they would start demanding to become citizens of Serbia. The Russian government considered Germany to be the main threat to its territory. This was reinforced by Germany's decision to form the Triple Alliance. Under the terms of this military alliance, Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy agreed to support each other if attacked by either France or Russia. Although Germany was ruled by the Tsar's cousin, Kaiser Wilhem II, he accepted the views of his ministers and in 1907 agreed that Russia should joined Britain and France to form the Triple Entente. (3) Russia had made considerable economic progress during the early years of the 20th century. By 1914 Russia was was annually producing some five million tons of pig-iron, four million tons of iron and steel, forty tons of coal, ten million tons of petroleum, and was exporting about twelve million tons of grain. However, Russia still lagged a long way behind other major powers. Industry in Russia employed not much more than five per cent of the entire labour force and contributed only about one-fifth of the national income. (4) Sergei Witte realised that because of its economic situation, Russia would lose a war with any of its rivals. Bernard Pares met Sergei Witte several times in the years leading up to the First World War: "Count Witte never swerved from his conviction, firstly, that Russia must avoid the war at all costs, and secondly, that she must work for economic friendship with France and Germany to counteract the preponderance of England." (5) In 1913, the Tsar approved a "great army programme". This included an increase in the size of the Russian Army by nearly 500,000 men as well as an extra 11,800 officers. It is claimed that Russia had the largest army in the world. This was made up of 115 infantry and 38 cavalry divisions. The Russian estimated manpower resource included more than 25 million men of combat age. (6) However, Russia's poor roads and railways made the effective deployment of these soldiers difficult and Germany was confident in being able to deal with this threat. (7) During the July Crisis in 1914, Sergei Witte joined forces with Pyotr Durnovo, the Minister of the Interior, and Gregory Rasputin, to urge the Tsar not to enter a war with Germany. Durnovo told the Tsar that a war with Germany would be "mutually dangerous" to both countries, no matter who won. Witte added that "there must inevitably break out in the conquered country a social revolution, which by the very nature of things, will spread to the country of the victor." (8) In the international crisis that followed the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Nicholas II accepted the advice of his foreign minister, Sergi Sazonov, and committed Russia to supporting the Triple Entente. Sazonov was of the opinion that in the event of a war, Russia's membership of the Triple Entente would enable it to make territorial gains from neighbouring countries. Sazonov was especially interested in taking Posen, Silesia, Galicia and North Bukovina. Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolayevitch told the Tsar: "Russia, if it did not mobilize, would face the greatest dangers and a peace bought with cowardice would unleash revolution at home." (9) On the outbreak of the First World War General Alexander Samsonov was given command of the Russian Second Army for the invasion of East Prussia. He advanced slowly into the south western corner of the province with the intention of linking up with General Paul von Rennenkampf advancing from the north east. General Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff were sent forward to meet Samsonov's advancing troops. They made contact on 22nd August, 1914, and for six days the Russians, with their superior numbers, had a few successes. However, by 29th August, Samsanov's Second Army was surrounded. (10) General Samsonov attempted to retreat but now in a German cordon, most of his troops were slaughtered or captured. The Battle of Tannenberg lasted three days. Only 10,000 of the 150,000 Russian soldiers managed to escape. Shocked by the disastrous outcome of the battle, Samsanov committed suicide. The Germans, who lost 20,000 men in the battle, were able to take over 92,000 Russian prisoners. On 9th September, 1914, General von Rennenkampf ordered his remaining troops to withdraw. By the end of the month the German Army had regained all the territory lost during the initial Russian onslaught. The attempted invasion of Prussia had cost Russia almost a quarter of a million men. (11) By December, 1914, the Russian Army had 6,553,000 men. However, they only had 4,652,000 rifles. Untrained troops were ordered into battle without adequate arms or ammunition. "Untrained troops were ordered into battle without adequate arms or ammunition. And because the Russian Army had about one surgeon for every 10,000 men, many wounded of its soldiers died from wounds that would have been treated on the Western Front. With medical staff spread out across a 500 mile front, the likelihood of any Russian soldier receiving any medical treatment was close to zero". (12) Tsar Nicholas II decided to replace Grand Duke Nikolai as supreme commander of the Russian Army fighting on the Eastern Front. He was disturbed when he received the following information from General Alexei Brusilov: "In recent battles a third of the men had no rifles. These poor devils had to wait patiently until their comrades fell before their eyes and they could pick up weapons. The army is drowning in its own blood." (13) On 7th July, 1915, the Tsar wrote to his wife, Alexandra Fedorovna, and complained about the problems he faced fighting the war: "Again that cursed question of shortage of artillery and rifle ammunition - it stands in the way of an energetic advance. If we should have three days of serious fighting we might run out of ammunition altogether. Without new rifles it is impossible to fill up the gaps.... If we had a rest from fighting for about a month our condition would greatly improve. It is understood, of course, that what I say is strictly for you only. Please do not say a word to anyone." (14) In 1916 two million Russian soldiers were killed or seriously wounded and a third of a million were taken prisoner. Millions of peasants were conscripted into the Tsar's armies but supplies of rifles and ammunition remained inadequate. It is estimated that one third of Russia's able-bodied men were serving in the army. The peasants were therefore unable to work on the farms producing the usual amount of food. By November, 1916, food prices were four times as high as before the war. As a result strikes for higher wages became common in Russia's cities. (15) Lenin, leader of the Bolsheviks, was appalled by the decision of most socialists in Europe to support the war effort. Living in exile in Switzerland, Lenin devoted his energies to campaign to turn the "imperialist war into a civil war". This included the publication of his book, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism. Along with his close collaborators, Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev, Lenin arranged for the distribution of propaganda that urged Allied troops to turn their rifles against their officers and start a socialist revolution. General Alexei Brusilov, commander of the Russian Army in the South West, led an offensive against the Austro-Hungarian Army in June, 1916. Initially Brusilov achieved considerable success and in the first two weeks his forces advanced 80km and captured 200,000 prisoners. The German Army sent reinforcements to help their allies and gradually the Russians were pushed back. When the offensive was called to a halt in the autumn of 1916, the Russian Army had lost almost a million men. Nicholas II, as supreme commander of the Russian Army, was now closely linked to the country's military failures and during 1917 there was a strong decline in his support in Russia. On 13th March, 1917, the Russian Army High Command recommended that Nicholas abdicate in favour of a more popular member of the royal family. Attempts were now made to persuade Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich to accept the throne. He refused and on the 1st March, 1917, the Tsar abdicated. A Provisional Government, headed by Prince George Lvov, was formed. Members of the Cabinet included Paul Miliukov, leader of the Cadet Party, was Foreign Minister, Alexander Guchkov, Minister of War, Alexander Kerensky, Minister of Justice, Mikhail Tereshchenko, a beet-sugar magnate from the Ukraine, became Finance Minister, Alexander Konovalov, a munitions maker, Minister of Trade and Industry, and Peter Struve, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Lvov attempted to maintain the Russian war effort but he was severely undermined by the formation of soldiers' committee that demanded "peace without annexations or indemnities". In May, 1917, Alexander Kerensky was appointed as Minister of War. He toured the Eastern Front where he made a series of emotional speeches where he appealed to the troops to continue fighting. On 18th June, Kerensky announced a new war offensive. Encouraged by the Bolsheviks, who favoured peace negotiations, there were demonstrations against Kerensky in Petrograd. The July Offensive, led by General Alexei Brusilov, was an attack on the whole Galician sector. Initially the Russian Army made advances and on the first day of the offensive took 10,000 prisoners. However, low morale, poor supply lines and the rapid arrival of German reserves from the Western Front slowed the advance and on 16th July the offensive was brought to an end. Soldiers on the Eastern Front were dismayed at the news and regiments began to refuse to move to the front line. There was a rapid increase in the number of men deserting and by the autumn of 1917 an estimated 2 million men had unofficially left the army. Some of these soldiers returned to their homes and used their weapons to seize land from the nobility. Manor houses were burnt down and in some cases wealthy landowners were murdered. Kerensky and the Provisional Government issued warnings but were powerless to stop the redistribution of land in the countryside. After the failure of the July Offensive on the Eastern Front, Kerensky replaced General Alexei Brusilov with General Lavr Kornilov, as Supreme Commander of the Russian Army. The two men soon clashed about military policy. Kornilov wanted Kerensky to restore the death-penalty for soldiers and to militarize the factories. Kerensky refused and sacked Kornilov. Kornilov responded by sending troops under the leadership of General Krymov to take control of Petrograd. Kerensky was now in danger and so he called on the Soviets and the Red Guards to protect Petrograd. The Bolsheviks, who controlled these organizations, agreed to this request, but in a speech made by their leader, Lenin, he made clear they would be fighting against Kornilov rather than for Kerensky. Within a few days Bolsheviks had enlisted 25,000 armed recruits to defend Petrograd. While they dug trenches and fortified the city, delegations of soldiers were sent out to talk to the advancing troops. Meetings were held and Kornilov's troops decided to refuse to attack Petrograd. General Krymov committed suicide and Kornilov was arrested and taken into custody. Kerensky now became the new Supreme Commander of the Russian Army. His continued support for the war effort made him unpopular in Russia and on 25th September, Kerensky attempted to recover his left-wing support by forming a new coalition that included more Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries. However, with the Bolsheviks controlling the Soviets, and now able to call on 25,000 armed militia, Kerensky was unable to reassert his authority. On 25th October, Kerensky was informed that the Bolsheviks were about to seize power. He decided to leave Petrograd and try to get the support of the Russian Army on the Eastern Front. Later that day the Red Guards stormed the Winter Palace and members of the Kerensky's cabinet were arrested. After failing to rally the troops against the new government, Kerensky fled to France Lenin, the new leader of the Russian government, immediately announced an armistice with the Central Powers. The following month, he sent Leon Trotsky, the people's commissar for foreign affairs, as head of the Russian delegation, to Brest-Litovsk to negotiate a peace deal with Germany and Austria. Trotsky had the difficult task of trying to end Russian participation in the First World War without having to grant territory to the Central Powers. By employing delaying tactics Trotsky hoped that socialist revolutions would spread from Russia to Germany and Austria-Hungary before he had to sign the treaty. After nine weeks of discussions without agreement, the German Army was ordered to resume its advance into Russia. On 3rd March 1918, with German troops moving towards Petrograd, Lenin ordered Trotsky to accept the terms of the Central Powers. The Brest-Litovsk Treaty resulted in the Russians surrendering the Ukraine, Finland, the Baltic provinces, the Caucasus and Poland. Almost 15 million served in the Russian Army during the First World War. Casualties totalled an estimated 1.8 million killed, 2.8 million wounded and 2.4 million taken prisoner.Triple Entente

Russian Rearmament

Russia and First World War: 1914-1916

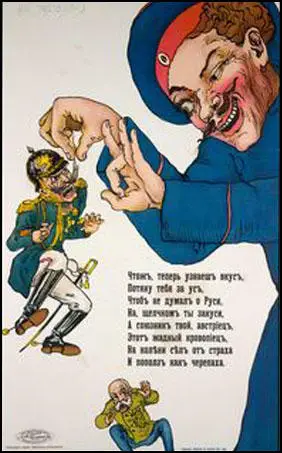

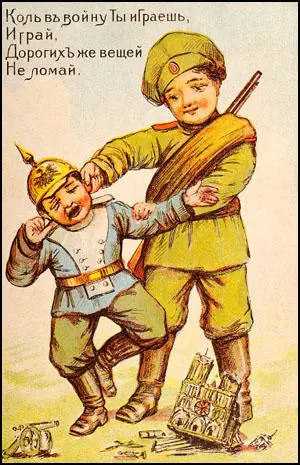

Surely the Germans will not get this far!.

The Tsar: But when our own army returns....?

K. J. Chamberlain, The Masses (January, 1915)

1917 Provisional Government

Brest-Litovsk Treaty

Primary Sources

(1) Stephen Graham, Russia and the World (1915)

I was staying in an Altai Cossack village on the frontier of Mongolia when the war broke out, a most verdant resting-place with a majestic fir forests, snow-crowned mountains range behind range, green and purple valleys deep in larkspur and monkshood. All the young men and women of the village were out of the grassy hills with scythes; the children gathered currants in the wood each day, and folks sat at home and sewed furs together, the pitch-boilers, and charcoal-burners worked at their black fires with barrels and scoops.

At 4 a.m. on 31st July the first telegram came through; an order to mobilize and be prepared for active service. I was awakened that morning by an unusual commotion, and, going into the village street, saw the soldier population collected in groups, talking excitedly. My peasant hostess cried out to me, "have you heard the news? There is war." A young man on a fine horse came galloping down the street, a great red flag hanging from his shoulders and flapping in the wind, and as he went he called out the news to each and every one, "War! War!"

Who was the enemy? Nobody knew. The telegram contained no indications. All the village population knew was that the same telegram had come as came ten years ago, when they were called to fight the Japanese. Rumours abounded. All the morning it was persisted that the yellow peril had matured, and that the war was with China. Russia had pushed too far into Mongolia, and China had declared war.

Then a rumour went round. "It is with England, with England." So far away these people lived they did not know that our old hostility had vanished. Only after four days did something like the truth come to us, and then nobody believed it.

"An immense war," said a peasant to me. "Thirteen powers engaged - England, France, Russia, Belgium, Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, Albania, against Germany, Austria, Italy, Romania, Turkey.

Two days after the first telegram a second came, and this one called up every man between the ages of eighteen and forty-three.

(2) Felix Yusupov was at first optimistic about Russia's chances of victory in the First World War.

The military campaigns had opened brilliantly by a deep break-through into East Prussia; the offensive was launched prematurely at the demand of the Allies to relieve the congested Western front. At the end of August, through lack of ordnance, General Samsonoff's army corps was surrounded near Tannenberg. The General, not wishing to survive the loss of his army, shot himself.

The offensive was successfully renewed on the Austrian front, but in February 1915 a further offensive in East Prussia ended in the disaster of Augustovo. On May 2nd, the Austro-German army broke through the South-Western Russian front. Our troops were underfed, ill-equipped, and had no ammunition, yet under these appalling conditions they fought against the best-equipped army in the world. Whole regiments were taken prisoner without having a chance to resist, owing to the lack of equipment which failed to arrive in time.

(3) Alan Woods, Tsarist Russia and the War (13 March 2015)

Thousands of Russian troops were sent to the front without proper equipment. They lacked everything: weapons, ammunition, boots or bedding. As many as a third of Russian soldiers were not issued with a rifle. In late 1914 Russia’s general headquarters reported that 100,000 new rifles were needed each month, but that Russian factories were capable of producing less than half this number (42,000 per month). The soldiers, however, were well armed with prayers, as Russian Orthodox bishops and priests worked diligently to bless those about to go into battle, showering them generously with holy water from a bucket....

By December, 1914, the Russian Army had 6,553,000 men. However, they only had 4,652,000 rifles. Untrained troops were ordered into battle without adequate arms or ammunition. And because the Russian Army had about one surgeon for every 10,000 men, many wounded of its soldiers died from wounds that would have been treated on the Western Front. With medical staff spread out across a 500 mile front, the likelihood of any Russian soldier receiving any medical treatment was close to zero.

(4) Arthur Ransome made several visits to the Eastern Front in 1916 and 1917.

I saw a great deal of that long-drawn out front and of the men who, ill-armed, ill-supplied, were holding it against an enemy who, even in his anxiety to fight was no greater than the Russian's, was infinitely better equipped. I came back to Petrograd full of admiration for the Russian soldiers who were holding the front without enough weapons to go round.

(5) Nicholas II, letter to Alexandra (7th July, 1915)

Again that cursed question of shortage of artillery and rifle ammunition - it stands in the way of an energetic advance. If we should have three days of serious fighting we might run out of ammunition altogether. Without new rifles, it is impossible to fill up the gaps. The army is now almost stronger than in peace time; it should be (and was at the beginning) three times as strong. This is the position we find ourselves in at present. If we had a rest from fighting for about a month, our condition would greatly improve. It is understood, of course, that what I say is strictly for you only. Please do not say a word of this to any one.

(6) In 1915 Hamilton Fyfe began reporting the war on the Eastern Front.

Brussilov was the ablest of the army-group commanders. His front was in good order. For that reason we were sent to it. The impression I got in April was the Russian troops, all the men and most of the officers, were magnificent material who were being wasted because of the incompetence, intrigues, and corruption of the men who governed the country.

In June Brussilov's advance showed what they could do, when they were furnished with sufficient weapons and ammunition. But that effort was wasted, too, for want of other blows to supplement it, for want of any definite plan of campaign.

The Russian officers, brutal as they often were to their men (many of them scarcely considered privates to be human), were as a rule friendly and helpful to us. They showed us all we wanted to see. They always cheerfully provided for Arthur Ransome (a fellow journalist), who could not ride owing to some disablement, a cart to get about in.

(7) Report from the Russian village of Grushevka (8th August, 1916)

The figures are: 115 (10 killed, 34 wounded, 71 missing or in captivity) out of 829 souls mobilized. Consequently, for the village of Grushevka the losses amount to 13 per cent of the total population of 3,307 souls. Harvesting and thrashing are going on everywhere, and there is hope that the work will be finished on time in the fall. In addition to women, children, and the aged, I have working for me 36 people from the Kherson jail, and 947 Austrian war prisoners.

(8) In his book My Reminiscences of the Russian Revolution, the journalist, Morgan Philips Price described Lavr Kornilov making a speech in Moscow on 25th August, 1917.

A wiry little little man with strong Tartar features. He wore a general's full-dress uniform with a sword and red-striped trousers. His speech was begun in a blunt soldierly manner by a declaration that he had nothing to do with politics. He had come there, he said, to tell the truth about the condition of the Russian army. Discipline had simply ceased to exist. The army was becoming nothing more than a rabble. Soldiers stole the property, not only of the State, but also of private citizens, and scoured the country plundering and terrorizing. The Russian army was becoming a greater danger to the peaceful population of the western provinces than any invading German army could be.

(9) Peter Wrangel, Memoirs of General Peter Wrangel (1929)

Towards the winter of 1916 the bloody struggles which had been waged throughout the summer and autumn drew to a close. We consolidated our position, filled in the gaps in our effective forces, and reorganized generally.

The experience gained from two years of warfare had not been acquired in vain. We had learnt a great deal, and the shortcomings for which we had paid so dearly were now discounted. A number of generals who had not kept pace with modern needs had had to give up their commands, and life had brought other more capable men to the fore. But nepotism, which permeated all spheres of Russian life, still brought unworthy men into important positions too often.

After two years of warfare, the Army was not what it had been. The majority of the original officers and men, especially the infantry, had been killed or put out of action. The new officers, hastily trained, and lacking military education and espirit de corps, could not make satisfactory instructors of the men. They found difficulty in enduring the dangers, fatigue, and privations of life at the front, and war to them meant nothing but suffering. It was impossible for them to inspire the troops and put fresh heart into their men.

Neither were the troops what they had been. The original soldiers, inured to fatigue and privation, and brave in battle, were better than ever; but there were few of them left. The new contingents were by no means satisfactory. The reserve forces were primarily fathers of families who had been dragged away from their villages, and were warriors only in spite of themselves. For they had forgotten that once upon a time they had been soldiers; they hated war, and thought only of returning to their homes as soon as possible.

(10) Statement issued by the Petrograd Soviet (9th April, 1917)

We are appealing to our brother proletarians of the Austro-German coalition. The Russian Revolution will not retreat before the bayonets of conquerors and will not allow itself to be crushed by military force. But we are calling to you, throw off your yoke of your semi-autocratic rule as the Russian people have shaken off the Tsar's and then by our united efforts we will stop the horrible butchery which is disgracing humanity and is beclouding the great days of the birth of Russian freedom. Proletarians of all countries unite.

(11) Paul Milyukov, Foreign Minister of the Provisional Government, letter sent to all Allied ambassadors (5th May, 1917)

Free Russia does not aim at the domination of other nations, or at occupying by force foreign territories. Its aim is not to subjugate or humiliate anyone. In referring to the "penalties and guarantees" essential to a durable peace the Provisional Government had in view reduction of armaments, the establishment of international tribunals, etc.

(12) Soon after the February Revolution the journalist Harold Williams interviewed Alexander Kerensky.

Last week's ridiculous manifesto (Order No 1), issued in the name of the Council of Workmen's Deputies (the Soviet), calling on the soldiers not to obey their officers, Kerensky sharply characterized as an act of provocation. There had been a few instances of grave disturbance of discipline, but the Minister was confident that this phase would soon pass, together with the other eccentricities. He declared: "The general effect of the liberation will, I am convinced, be to give an immense uplift to the spirit of the troops, and so to shorten the war. We are for iron discipline in working hours, but out of working hours we want the soldiers to feel they are also free men."

(13) Alfred Knox, diary entry (20th July, 1917)

Events have moved with dramatic quickness. Kerensky returned from the front last night and, in a stormy meeting of the Ministry, demanded dictatorial powers in order to bring the army back to discipline. The socialists disagreed. Lvov and Tereshchenko did their utmost to reconcile the diverging views. While addressing the men he was handed a telegram telling him of the disaster on the South-West Front, where the Germans have broken through. He took back the telegram to the Ministerial Council and the attitude changed. Lvov has resigned and Kerensky will be Prime Minister and Minister of War.

(14) Erich Maria Remarque, All Quiet on the Western Front (1929)

I am often on guard over the Russians. In the darkness one sees their forms move like stick storks, like great birds. They come close up to the wire fence and lean their faces against it. Their fingers hook round the mesh. Often many stand side by side, and breathe the wind that comes down from the moors and the forest.

They rarely speak and then only a few words. They are more human and more brotherly towards one another, it seems to me, than we are. But perhaps that is merely because they feel themselves to be more unfortunate than us. Anyway the war is over so far as they are concerned. But to wait for dysentery is not much of a life either.

A word of command has made these silent figures our enemies; a word of command might transform them into our friends. At some table a document is signed by some persons whom none of us knows, and then for years together that very crime on which formerly the world's condemnation and severest penalty fall, becomes our highest aim. Any non-commissioned officer is more of an enemy to a recruit, any schoolmaster to a pupil, then they are if they were free.

(15) In the summer of 1917 Ernest Poole visited the rural areas of Russia. This included an interview with a farmer who was a member of a village cooperative.

Our cooperative store has still quite a stock of goods, and the steadier peasants all belong. We have eighteen hundred members now. Each paid five roubles to buy a share. There were six thousand purchasers last year; and because we charge higher prices to outsiders than to members, so many more peasants wish to join that we are almost ready to announce a second issue of stock.

Of course, our progress has been blocked by the war and the revolution. Goods have gone up to ruinous rates. Already we are nearly out of horseshoes, axes, harrows, ploughs. Last spring we had not ploughs enough to do the needed ploughing, and that is why our crop is short. There is not enough rye in the district to take us through the winter, let alone to feed the towns. And so the town people will starve for awhile - and sooner or later, I suppose, they will finish with their wrangling, start their mills and factories, and turn out the ploughs and tools we need.

(16) Albert Rhys Williams, Through the Russian Revolution (1923)

In thousands the soldiers were throwing down their guns and streaming from the front. Like plagues of locusts they came, clogging railways, highways and waterways. They swarmed down on trains, packing roofs and platforms, clinging to car-steps like clusters of grapes, sometimes evicting passengers from their berths.

The ruling-class used every device to keep those weapons in the soldiers' hands. It waved the flag and screamed "Victory and Glory." It organized Women's Battalions of Death crying "Shame on you men to let girls do your fighting." It placed machine-guns in the rear of rebelling regiments declaring certain death to those who retreated.

(17) Louise Bryant, Six Months in Russia (1918)

One of the things that strikes coldness to one's heart are the long lines of scantily clad people standing in the bitter cold waiting to buy bread, milk, sugar or tobacco. From four o'clock in the morning they begin to stand there.

(18) John Reed, Ten Days That Shook the World (1919)

The policy of the Provisional Government alternated between ineffective reforms and stern repressive measures. An edict from the Socialist Minister of Labour ordered all the Workers' Committees henceforth to meet only after working hours. Among the troops at the front, 'agitators' of opposition political parties were arrested, radical newspapers closed down, and capital punishment applied - to revolutionary propagandists. Attempts were made to disarm the Red Guard. Cossacks were spent order in the provinces.

In September 1917, matters reached a crisis. Against the overwhelming sentiment of the country, Kerensky and the 'moderate' Socialists succeeded in establishing a Government of Coalition with the propertied classes; and as a result, the Mensheviki and Socialist Revolutionaries lost the confidence of the people for ever.

Week by week food became scarcer. The daily allowance of bread fell from a pound and a half to a pound, than three-quarters, half, and a quarter-pound. Towards the end there was a week without any bread at all. Sugar one was entitled to at the rate of two pounds a month - if one could get it at all, which was seldom. A bar of chocolate or a pound of tasteless candy cost anywhere from seven to ten roubles - at least a dollar. For milk and bread and sugar and tobacco one had to stand in queue. Coming home from an all-night meeting I have seen the tail beginning to form before dawn, mostly women, some babies in their arms.

Student Activities

Russian Revolution Simmulation

Bloody Sunday (Answer Commentary)

1905 Russian Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Russia and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

The Life and Death of Rasputin (Answer Commentary)

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)