Herbert Hoover

Herbert Hoover, the son of a Jessie Hoover, a blacksmith and Hulda Minthorn Hoover, was born in West Branch, Iowa, on 10th August, 1874. Both his parents were Quakers. Jessie, a successful businessman died in 1880. Hulda, a Quaker minister, frequently left her three children, Herbert, his older brother Theodore, and his younger sister Mary, in the care of friends, to "proclaim the word of God". Hulda died of pneumonia in 1884. (1)

Hoover, aged nine, went to live with his grandmother in Kingsley before being taken in by his uncle, Dr. John Minthorn, a physician and businessman whose own son had died the year before. Hoover was encouraged to work hard at school but at the age of thirteen he was forced to work as office assistant at his uncle's real estate office in Salem, Oregon. (2)

Hoover continued to attend night school and in 1891 was able to enter Stanford University. He had to do a variety of odd jobs to support himself, and struggled in many of his classes, especially English. But he enjoyed university life and eventually decided to concentrate on geology. He fell in love with Lou Henry but was unable to afford to get married. Hoover graduated in 1895, and initially struggled to find a job. (3)

Eventually he found work as an engineer in the gold mining industry in California. In 1897 he moved to Western Australia in 1897 as an employee of Bewick, Moreing & Co., a London-based company. After being appointed as manager at the age of 23, he brought in many Italian immigrants to under-cut the costs of employing local men. Hoover became a strong opponent of trade unions who were attempting to improve the pay and conditions of the miners. In 1898, Hoover was made a junior partner and this increase in his wages enabled him to marry his college girlfriend, Lou Henry. Hoover and his wife had two children: Herbert Charles Hoover and Allan Henry Hoover. (4)

In April 1899, Hoovers relocated to China. Hoover worked as chief engineer for the Chinese Bureau of Mines, and as general manager for the Chinese Engineering and Mining Corporation (CEMC). Under his influence the company became a supplier of immigrant labor from Southeast Asia for South African mines. (5) By 1906, over 50,000 immigrants had been recruited and shipped by CEMC. In February, 1911, Winston Churchill was forced to answer questions in the House of Commons about the working and living conditions of these workers and soon afterwards the scheme was abandoned in 1911. (6)

The First World War

Herbert Hoover became an independent mining consultant. He specialized in rejuvenating troubled mining operations, taking a share of the profits in exchange for his technical and financial expertise. He also helped increase copper production in Russia, through the use of pyretic smelting. Hoover was also employed by Tsar Nicholas II to manage mines in the Altai Mountains. By 1914, Hoover was a very wealthy man, with an estimated personal fortune of $4 million. (7)

On the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, Hoover helped organize the return of around 120,000 Americans from Europe. He led 500 volunteers in distributing food, clothing, steamship tickets and cash. Hoover agreed to organize a relief effort with the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB). As chairman of the CRB, Hoover arranged the importation of millions of tons of foodstuffs for Belgian citizens. Hoover was given a $11-million-a-month budget for the work. Based in London for the next two years, arranged the distribution of over two million tons of food to nine million war victims. (8)

Germany was confident that they could bring Britain to collapse before American intervened. As A. J. P. Taylor pointed out: "They nearly succeeded. The number of ships sunk by U-boats rose catastrophically. In April 1917 one ship out of four leaving British ports never returned. That month nearly a million tons of shipping were sunk, two thirds of it British. New building could replace only one ton in ten. Neutral ships refused cargoes for British ports. The British reserve of wheat dwindled to six weeks' supply." (9)

When the USA declared war in April 1917, President Woodrow Wilson sent the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) under the command of General John Pershing to the Western Front. The Selective Service Act, drafted by Brigadier General Hugh Johnson, was quickly passed by Congress. The law authorized President Wilson to raise a volunteer infantry force of not more than four divisions. (10)

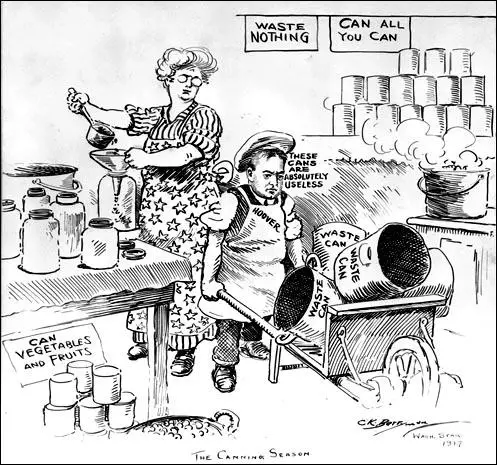

On 10th August, 1917, Hoover was appointed as head of the United States Food Administration, an agency responsible for the administration of the U.S. army overseas and allies' food reserves. The new law forbade hoarding, waste, and "unjust and unreasonable" prices and required businesses to be licensed. During this period "Hooverize" entered the dictionary as a synonym for economizing on food. (11)

One senator protested that Wilson had given Hoover "a power such as no Caesar ever employed over a conquered province in the bloodiest days of Rome's bloody despotism". Hoover replied that, "Winning a war requires a dictatorship of some kind or another. A democracy must submerge itself temporarily in the hands of an able man or an able group of men. No other way has ever been found." (12)

Hoover's main objectives was to persuade farmers to grow more and grocery shoppers to buy less so that surplus food should be sent to America's overseas allies. Hoover established set days for people to avoid eating specified foods and save them for soldiers' rations. For example, people were told not to eat meat on Mondays. In January, 1918, Hoover announced "the law of supply and demand... had been suspended." (13)

As head of the Food Administration's Grain Corporation, Hoover informed millers that if they did not sell flour to the government at a price he determined, he would requisition it, and he told bakers they must make "victory bread or close." In another speech Hoover argued: "The law is not sacred... Its unchecked operation might even jeopardize our success in war... It is imperative... that economic thinkers denude themselves of their procrustean forumulas of supply and demand... for in a crisis... government must necessarily regulate the price, and all theories to the contrary go by the board." (14)

A network of 1,200 Price Interpreting Boards announced "fair prices" which were published in newspapers so that housewives might boycott any grocer or butcher who did not fall into line. "We need to put the stamp of shame on wasteful eating, dressing and display of jewelry." To enforce these rules Hoover relied on his "one police force - the American woman". He urged them to complain to the authorities if they discovered the owners of shops were trying to avoid government regulations. (15)

Hoover told Wilson that his measures had not only delivered over $1.4 billion worth of food to Europe but had prevented food riots in American cities that would have resulted in "blood in our gutters". He told the congressional committee that democracy had triumphed because of "its willingness to yield to dictatorship". Hoover was attacked by some people for allowing some companies to make great profits from the scheme he had introduced. (16)

The Paris Peace Conference opened in January 1919. Hoover as director-general of Inter-Ally Supreme Council for Relief and Supply, also attended. President Woodrow Wilson argued strongly that it was vitally important to provide food for the German people in order to prevent a Bolshevik revolution. Hoover agreed and the decision to supply the Germans with 270,000 tons of food on 12th January. It has been claimed that Hoover was desperate to unload his "abundant stocks of low-grade pig products at high prices". (17)

Bernard Baruch, was on President's Wilson's staff and saw a lot of him during the conference, but the contact failed to foster a close mutual understanding. At a dinner party Baruch saw "Hoover, flanked by beautiful women, stared distractedly at his plate. Baruch, who was as loath to squander an opportunity to engage the opposite sex as the relief director was to waste food, afterward asked him how he could have ignored such charming companions. Hoover didn't seem to understand the question". (18)

David Lloyd George put in a claim for £25 billion of reparations at the rate of £1.2 billion a year. Georges Clemenceau wanted £44 billion, whereas Woodrow Wilson said that all Germany could afford was £6 billion. John Maynard Keynes, Lloyd George's economic adviser, disagreed with all these figures. He argued that Germany could only afford to pay £2 billion and if these higher figures were accepted it would ruin the economy of Europe. (19) Keynes found that Hoover was one of the few people at the conference who understood these economic arguments. Keynes wrote soon afterwards: "Mr. Hoover was the only man who emerged from the ordeal of Paris with an enhanced reputation." (20)

Secretary of Commerce

In 1920, both Democrats and Republicans considered asking Hoover to become their presidential candidate. It was suggested that Franklin D. Roosevelt could be Hoover's running-mate. Roosevelt agreed with the suggestion: "Hoover is certainly a wonder. I wish I could make him President of the United States. There could not be a better one." (21) Colonel Edward House agreed: "It's a wonderful idea. A Hoover-Roosevelt ticket is probably the only chance the Democrats have in November." (22)

On 6th March, 1920, Roosevelt and his wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, met Hoover to discuss the issue. Afterwards she wrote: "Mr. Hoover talked a great deal. He has an extraordinary knowledge and grasp of present-day problems." (23) At the end of March, Hoover broke his long silence and announced that he intended to be a candidate for the Republican nomination. However, he was defeated by Warren Harding. It was claimed that he "conducted a highly amateur campaign for the nomination; the politicians dismissed him with a sour laugh." (24)

The United States entered the 1920's in a strong economic position. The economies of her European rivals had been severely disrupted by the First World War and the United States had been able to capture markets which had previously been supplied by countries like Britain, France and Germany. Harding's isolationist foreign policy was popular with the electorate and in the 1920 Presidential Election he was voted into office by the widest popular margin in history. (25)

After the election Harding appointed Hoover as his Secretary of Commerce. Hoover demanded, and received, authority from Harding to coordinate economic affairs throughout the government. He created many sub-departments and committees, overseeing and regulating large areas of industry. In some cases he "seized" control of responsibilities from other Cabinet departments when he deemed that they were not carrying out their responsibilities well. As a result of this behaviour he became known as the "Secretary of Commerce and Under-Secretary of all other departments." (26)

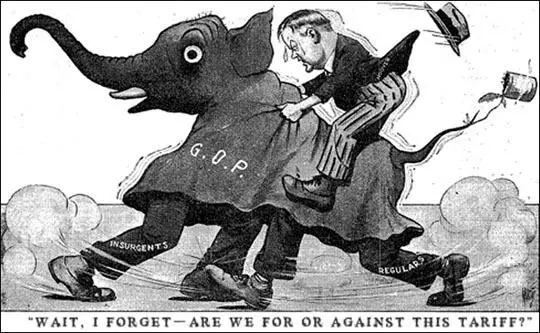

During the campaign Warren Harding, promised to take measures to protect American farmers. It was thought that the rates under the Underwood-Simmons Tariff was too low. Joseph Fordney, the chair of the House Ways and Means Committee, and Porter McCumber, the chair of the Senate Finance Committee, introduced a bill which authorized the "Tariff Commission, working in an 'expert' and unpolitical way (and thus supposedly also independently of economic interests), to set rates so as to equalize the difference between American and foreign costs of production." (27)

In September 1922, the Fordney–McCumber Tariff Act was signed by President Harding. These raised tariffs to levels higher than any previously in American history in an attempt to bolster the post-war economy, protect new war industries, and aid farmers. "Duties on chinaware, pig iron, textiles, sugar, and rails were restored to the high levels of 1907 and increases ranging from 60 to 400 per cent were established on dyes, chemicals, silk and rayon textiles, and hardware." (28) Over the next eight years it raised the American ad valorem tariff rate to an average of about 38.5% for dutiable imports and an average of 14% overall. (29)

In the 1920s Hoover was associated with the successful growth in the American economy. This was partly due to the introduction of mass production. For example, between 1919 and 1929 output per worker increased by 43%. This increase enabled America to produce items that were cheaper than those manufactured by her European competitors. This enabled employers to pay higher wages. Hoover pointed out: "I think our people have long realized the advantages of large business operations in improving and cheapening the cost of manufacture and distribution…. The more goods produced, the more share there is to distribute." (30)

The United States also pioneered techniques in persuading people to buy the latest products. The development of commercial radio meant that companies could communicate information about their goods to a mass audience. In order to encourage people to purchase expensive goods like motor cars, refrigerators and washing machines, the system of hire-purchase was introduced which allowed customers to pay for these goods by installments.

President Warren Harding died suddenly on 2nd August, 1923, in San Francisco, and was replaced by his vice-president, Calvin Coolidge. The following year, Coolidge easily won the 1924 Presidential Election with 54% of the vote. Hoover remained Secretary of Commerce and the economy continued to grow and so did the industrial wage. This enabled the workers to buy the goods they were making. For example, by 1926 the average daily wage of a Ford worker was $10 and the Model T sold for only $350. (31)

Andre Siegfried, a French visitor pointed out: "In America the daily life of the majority is conceived on a scale that is reserved for the privileged classes anywhere else... The use of the telephone, for instance, is very widespread. In 1925 there were 15 subscribers for every 100 inhabitants as compared with 2 in Europe, and some 49,000,000 conversations per day.... Wireless is rapidly winning a similar position for itself, for even in 1924 the farmers alone possessed over 550,000 radios.... Statistics for 1925 show that... the United States owned 81 per cent of all the automobiles in existence, or one for every 5.6 people, as compared with one for every 49 and 54 in Great Britain and France." (32)

The real wages of industrial workers increased by about 10 per cent in the 1920s. However, productivity rose by more than 40%. Semi-skilled and unskilled workers in mass production, who were not unionized, lagged far behind skilled craftsmen and therefore was a growth in inequality: "The average industrial wage rose from 1919's $1,158 to $1,304 in 1927, a solid if unspectacular gain, during a period of mainly stable prices... The twenties brought an average increase in income of about 35%. But the biggest gain went to the people earning more than $3,000 a year.... The number of millionaires had risen from 7,000 in 1914 to about 35,000 in 1928." (33)

The farming community had not enjoyed the benefits of this growing economy. The Fordney–McCumber Tariff Act caused serious problems for the farmers. Senator David Walsh pointed out that farmers were net exporters and so did not need protection from tariffs. He explained that American farmers depended on foreign markets to sell their surplus. The price of farming machinery also increased. For example, the average cost of a harness rose from $46 in 1918 to $75 in 1926, the 14-inch plow rose from $14 to $28, mowing machines rose from $45 to $95, and farm wagons rose from $85 to $150. Statistics of the Bureau of Research of the American Farm Bureau that showed farmers had lost more than $300 million annually as a result of the tariff. (34)

As Patrick Renshaw has pointed out: "The real problem was that in both agricultural and industrial sectors of the economy America's capacity to produce was tending to outstrip its capacity to consume. This gap had been partly bridged by private debt, easy credit, easy credit and hire purchase. But this would collapse if anything went wrong in another part of the system." (35)

1928 Presidential Election

President Calvin Coolidge announced in August 1927 that he would not seek a second full term of office. Coolidge was unwilling to nominate Hoover as his successor. The two men had a poor relationship on one occasion he remarked that "for six years that man has given me unsolicited advice - all of it bad. I was particularly offended by his comment to 'shit or get off the pot'." (36)

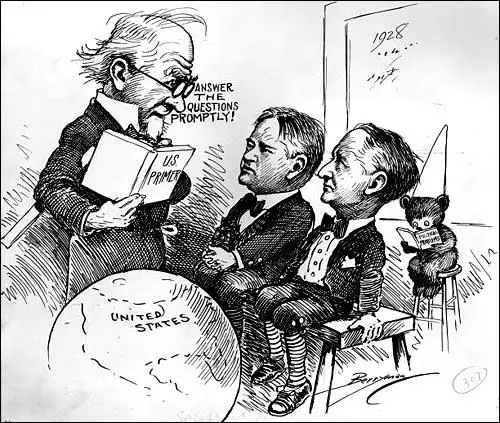

Coolidge was not alone in thinking that Hoover might be a bad candidate. Republican leaders cast about for an alternative candidate such as Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon and the former Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes, Despite these reservations, Hoover won the presidential nomination on the first ballot of the convention. Senator Charles Curtis of Kansas was selected as his running-mate. One newspaper reported: "Hoover brings character and promise to the Republican ticket. He is a new kind of candidate in a day surfeited with old forms and old habits in politics." (37)

Senator George H. Moses, chairman of the Republican national convention, sent a letter congratulating Hoover on his nomination. He replied: "You convey too great a compliment when you say that I have earned the right to the presidential nomination. No man can establish such an obligation upon any part of the American people. My country owes me no debt. It gave me, as it gives every boy and girl, a chance. It gave me schooling, independence of action, opportunity for service and honor. In no other land could a boy from a country village, without inheritance or influential friends, look forward with unbounded hope. My whole life has taught me what America means. I am indebted to my country beyond any human power to repay." (38)

One of the main issues in the 1928 Presidential Election campaign was the taxes imposed on imports. The Fordney-McCumber Act of 1922 raised American tariffs on many imported goods to protect factories and farms. The tariff rate was an average of about 38.5% for dutiable imports and an average of 14% overall. However, in response to this, most of American trading partners had raised their own tariffs to counter-act this measure. (40)

Industrialists such as Henry Ford attacked the tariff and argued that the American automobile industry did not need protection since it dominated the domestic market and its main objective was to expand foreign sales. He pointed out that France raised its tariffs on automobiles from 45% to 100% in response to the Fordney-McCumber Act. Ford and other industrialists tended to favour the idea of free trade. (41)

David Walsh, a member of the Democratic Party, challenged the tariff by arguing that the farmers were net exporters and so did not need protection; they depended on foreign markets to sell their surplus. Hoover and the Republicans still believed in tariffs. William Borah, the charismatic senator from Idaho, widely regarded as a true champion of the American farmer, had a meeting with Hoover and offered to give him his full support if he promised to increase tariffs of agricultural products if elected. (42) Nearly a quarter of the American labour force was then employed on the land and Hoover wanted their vote. He therefore agreed with the proposal and during the campaign promised the American electorate that he would revise the tariff. (43)

The Democratic candidate was Al Smith. As governor of New York he attempted to bring an end to child labour, improve factory laws, housing and the care of the mentally ill. During his campaign Smith gave his support for an increase to the tariffs for imported goods, even though most of the party leaders, including Cordell Hull, John J. Raskob, Burton K. Wheeler and Harry F. Byrd, were strong opponents of the Fordney-McCumber Act. (44)

Smith was the first Roman Catholic to be a serious candidate for the presidency. This became a serious problem in the Deep South and the Ku Klux Klan burned Smith's effigy and Catholics were vilified for letting blacks worship in the same churches as whites. In the 1928 Presidential Election several states that had previously voted Democrat, such as Texas, Florida, Tennessee, Kentucky and Virginia voted Republican. Smith won 40.8% of the vote compared to Hoover's 58.2%. (45)

Carter Field argued that the business community was pleased with the election of Hoover: "In the months following the election of Hoover, in 1928, there was a wild stock-market boom. Most speculators, most businessmen, most people thought the country was moving on to a new high plateau of prosperity. Hoover was the miracle man. He knew about business and would help it prosper. Stocks were already high the day Hoover was elected; for example, American Telephone, which was sold around 150 in the spring of 1927 and was about 200 on election day, 1928, soared to a high above 310." (46)

After his election Hoover asked Congress for an increase of tariff rates for agricultural goods and a decrease of rates for industrial goods. Reed Smoot from Utah and chairman of the Senate Finance Committee and Willis C. Hawley, from Oregon, the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, agreed to sponsor the proposed bill. In the House of Representatives the president's bill was completely changed and now included rate hikes covering 887 specific products. (47) Smoot and Hawley argued that raising the tariff on imports would alleviate the over-production problem. In May 1929, the House of Representatives passed the Smoot–Hawley Tariff bill on a vote of 264 to 147, with 244 Republicans and 20 Democrats voting in favor of the bill. (48)

The Smoot–Hawley Tariff bill was then debated in the Senate. It came under attack from Democrats. Reed Smoot defended the bill by arguing: "This government should have no apology to make for reserving America for Americans. That has been our traditional policy. ever since the United States became a nation. We have returned to participate in the political intrigues of Europe, and we will not compromise the independence of this country for the privilege of serving as schoolmaster for the world. In economics as in politics, the policy of the government is, 'America First'. The Republican Party will not stand by and see economic experimenters fritter away our national heritage." (49)

Wall Street Crash

One way of making money during the 1920's was to buy stocks and shares. Prices of these stocks and shares constantly went up and so investors kept them for a short-term period and then sold them at a good profit. As with consumer goods, such as motor cars and washing machines, it was possible to buy stocks and shares on credit. This was called buying on the "margin" and enabled "speculators" to sell off shares at a profit before paying what they owed. In this way it was possible to make a considerable amount of money without a great deal of investment. During the first week of December, 1927, "more shares of stock had changed hands than in any previous week in the whole history of the New York Stock Exchange." (50)

The share price of Montgomery Ward, the mail-order company, went from $132 on 3rd March, 1928, to $466 on 3rd September, 1928. Whereas Union Carbide & Carbon for the same period went from $145 to $413; American Telephone & Telegraph from $77 to $181; Westinghouse Electric Corporation from $91 to $313 and Anaconda Copper from $54 to $162. (51)

John J. Raskob, a senior executive at General Motors, published an article, Everybody Ought to be Rich in August, 1929, where he pointed out: "The common stocks of their country have in the past ten years increased enormously in value because the business of the country has increased. Ten dollars invested ten years ago in the common stock of General Motors would now be worth more than a million and a half dollars. And General Motors is only one of may first-class industrial corporations." He then went on to say: "If a man saves $15 a week, and invests in good common stocks, and allows the dividends and rights to accumulate, at the end of twenty years he will have at least $80,000 and an income from investments of around $400 a month. He will be rich. And because income can do that, I am firm in my belief that anyone not only can be rich, but ought to be rich." (52)

Cecil Roberts, a British journalist working in the United States, pointed out that the stock market hysteria reached its apex in the summer of 1929. "Everyone gave you tips for a rise. Every was playing the market. Stocks soared dizzily. I found it hard not to be engulfed. I had invested my American earnings in good stocks. Should I sell for a profit? Everyone said, 'Hang on - it's a rising market'. On my last day in New York I went down to the barber. As he removed the sheet he said softly, 'Buy Standard Gas. I've doubled. It's good for another double.' As I walked upstairs, I reflected that if the hysteria had reached the barber-level, something must soon happen." (53)

Alec Wilder, the songwriter, became concerned about the value of his shares: "I knew something was terribly wrong because I heard bellboys, everybody, talking about the stock market. In August 1929 I persuaded my mother in Rochester to let me talk to our family adviser. I wanted to sell stock which had been left me by my father.... I talked to this charming man and told him I wanted to unload this stock. Just because I had this feeling of disaster. He got very sentimental: 'Oh your father wouldn't have liked you to do that.' He was so persuasive, I said O.K. I could have sold it for $160,000. Four years later, I sold it for $4,000." (54)

On 3rd September 1929 the stock market reached an all-time high. In the weeks that followed prices began to slowly decline. Later that month, an incident took place in London that caused major problems on Wall Street. In April 1929 Clarence Hatry, the former owner of Leyland Motors, acquired control of United Steel by borrowing "£789,000 from banks on the security of forged Corporation and General scrip certificates ascribed to the municipalities of Gloucester, Wakefield, and Swindon. £822,000 was withheld from these three corporations and another £700,000 was raised by duplicating shares in other companies he had promoted. As rumours about the Hatry companies circulated in the City, he spent large sums vainly trying to support their share values." (55)

On 20th September, 1929, Hatry voluntarily confessed his frauds to Sir Archibald Bodkin, director of public prosecutions. The economist John Kenneth Galbraith, described Hatry as "one of those curiously un-English figures with whom the English periodically find themselves unable to cope." (56) The news of this corrupt activity caused the London Stock Exchange to crash. This greatly weakened the optimism of American investment in markets overseas and caused further falls in the value of shares on Wall Street. (57)

Efforts were made to regain confidence in the state of the American economy. Irving Fisher, professor of political economy at Yale University, was considered the most important economist of the 1920s. His research on the quantity theory of money inaugurated the school of macroeconomic thought known as monetarism. On 17th October, 1929 he was reported as telling the Purchasing Agents Association that stock prices had reached "what looks like a permanently high plateau". He added that he expected to see the stock market, within a few months, "a good deal higher than it is today." (58)

Despite Fisher's prediction, on 24th October, over 12,894,650 shares were sold. Prices fell dramatically as sellers tried to find people willing to buy their shares. That evening, five of the country's bankers, led by Charles Edward Mitchell, chairman of the National City Bank, issued a statement saying that due to the heavy selling of shares, many were now under-priced. This statement failed to halt the reduction in demand for shares. (59) Two days later, President Hoover claimed: "The fundamental business of the country - that is, the production and distribution of goods and services - is on a sound and prosperous basis." (59a)

The New York Times reported: "The most disastrous decline in the biggest and broadest stock market of history rocked the financial district yesterday.... It carried down with it speculators, big and little, in every part of the country, wiping out thousands of accounts. It is probable that if the stockholders of the country's foremost corporations had not been calmed by the attitude of leading bankers and the subsequent rally, the business of the country would have been seriously affected. Doubtless business will feel the effects of the drastic stock shake-out, and this is expected to hit the luxuries most severely." (60)

On the opening of the Wall Street Stock Exchange on 29th October, 1929, John D. Rockefeller, the American oil industry business magnate and successful industrialist, issued a statement which attempted to regain confidence in the state of the economy: "Believing that fundamental conditions of the country are sound and that there is nothing in the business situation to warrant the destruction of values that has taken place on the exchanges during the past week, my son and I have for some days been purchasing sound common stocks." (61)

This did not have the desired impact on the market for that day over 16 million shares were sold. The market had lost 47 per cent of its value in twenty-six days. "Efforts to estimate yesterday's market losses in dollars are futile because of the vast number of securities quoted over the counter and on out-of-town exchanges on which no calculations are possible. However, it was estimated that 880 issues, on the New York Stock Exchange, lost between $8,000,000,000 and $9,000,000,000 yesterday. Added to that loss is to be reckoned the depreciation on issues on the Curb Market, in the over the counter market and on other exchanges." (62)

Although less than one per cent of the American people actually possessed stocks and shares, the Wall Street Crash was to have a tremendous impact on the whole population. The fall in share prices made it difficult for entrepreneurs to raise the money needed to run their companies. Frederick Lewis Allen pointed out: "Billions of dollars' of profits - and paper profits - had disappeared. The grocer, the window-cleaner, and the seamstress had lost their capital. In every town there were families which had suddenly dropped from showy affluence into debt. Investors who had dreamed of retiring to live on their fortunes now found themselves back once more at the very beginning of the long road to riches. Day by day the newspapers printed the grim reports of suicides." (63)

On 3rd December 1929, President Hoover addressed the nation on the Wall Street crash. "I have... instituted systematic, voluntary measures of cooperation with the business institutions and with State and municipal authorities to make certain that fundamental businesses of the country shall continue as usual, that wages and therefore consuming power shall not be reduced, and that a special effort shall be made to expand construction work in order to assist in equalizing other deficits in employment... I am convinced that through these measures we have reestablished confidence. Wages should remain stable. A very large degree of industrial unemployment and suffering which would otherwise have occurred has been prevented. Agricultural prices have reflected the returning confidence. The measures taken must be vigorously pursued until normal conditions are restored." (64)

Within a short time, 100,000 American companies were forced to close and consequently many workers became unemployed. As there was no national system of unemployment benefit, the purchasing power of the American people fell dramatically. This in turn led to even more unemployment. Yip Harburg pointed out that before the Wall Street Crash, the American citizen thought: "We were the prosperous nation, and nothing could stop us now.... There was a feeling of continuity. If you made it, it was there forever. Suddenly the big dream exploded. The impact was unbelievable." (65)

Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act

The Senate debated the Smoot-Hawley Tariff bill until March 1930, with many Senators trading votes based on their states' industries. Eventually, the revised bill proposed raising taxes on more than 20,000 imported goods to record levels. Willis C. Hawley predicted that it would bring "a renewed era of prosperity". Another supporter, Frank Crowther, argued that "business confidence will be immediately restored. We shall gradually work out of the temporary slump we have been in for the last few months... We shall dissipate the dark clouds of your gloomy prophecy with the rising sunshine of continued prosperity." (66)

The Smoot-Hawley bill was passed in the Senate on a vote of 44 to 42, with 39 Republicans and 5 Democrats voting in favor of the bill. In an attempt to persuade Hoover to veto the legislation, 1,028 American economists, including Irving Fisher, professor of political economy at Yale University, who was considered the most important economist of the period, published a open letter on the subject. (67)

"We are convinced that increased protective duties would be a mistake. They would operate, in general, to increase the prices which domestic consumers would have to pay. By raising prices they would encourage concerns with higher costs to undertake production, thus compelling the consumer to subsidize waste and inefficiency in industry. At the same time they would force him to pay higher rates of profit to established firms which enjoyed lower production costs. A higher level of protection, such as is contemplated by both the House and Senate bills, would therefore raise the cost of living and injure the great majority of our citizens."

The letter went on to point out that since the Wall Street Crash had resulted in much higher-rates of unemployment: "America is now facing the problem of unemployment. Her labor can find work only if her factories can sell their products. Higher tariffs would not promote such sales. We can not increase employment by restricting trade. American industry, in the present crisis, might well be spared the burden of adjusting itself to new schedules of protective duties. Finally, we would urge our Government to consider the bitterness which a policy of higher tariffs would inevitably inject into our international relations. The United States was ably represented at the World Economic Conference which was held under the auspices of the League of Nations in 1927. This conference adopted a resolution announcing that 'the time has come to put an end to the increase in tariffs and move in the opposite direction.' The higher duties proposed in our pending legislation violate the spirit of this agreement and plainly invite other nations to compete with us in raising further barriers to trade. A tariff war does not furnish good soil for the growth of world peace." (68)

Henry Ford spent an evening at the White House trying to convince Hoover to veto the bill, calling it "an economic stupidity." Thomas W. Lamont, the chief executive of J. P. Morgan Investment Bank said he "almost went down on his knees to beg Herbert Hoover to veto the asinine Hawley-Smoot tariff." He warned that the act would intensify "nationalism all over the world.” (69)

President Hoover considered the bill "vicious, extortionate, and obnoxious" but according to his biographer, Charles Rappleye, "the president could hardly turn its back on a measure endorsed by a clear majority of his own party." (70) Hoover signed the bill on 17th June, 1930. The Economist Magazine argued that the passing of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act was "the tragic-comic finale to one of the most amazing chapters in world tariff history… one that Protectionist enthusiasts the world over would do well to study.” (71)

At the time the Smoot-Hawley bill was passed the United States had 4.3 million unemployed. By 1932 it was 12.0 million. The economist, David Blanchflower, has argued that the "Smoot-Hawley Tariff proved to be the most damaging piece of trade legislation in US history." (72)

Andrew Mellon was Hoover's secretary of the treasury. Mellon followed policies that involved cutting income tax rates and reducing public spending. He also brought an end to the excess profits tax. Mellon's policies created a great deal of controversy and he was accused of following policies that favoured the wealthy. The economic depression that began in 1929 was partly blamed on Mellon's policies. (73)

Bonus Army

In May 1924 Congress voted $3,500,000,000 to the American veterans of the First World War. President Calvin Coolidge vetoed the bill saying: "patriotism... bought and paid for is not patriotism." However, Congress overrode his veto a few days later, enacting the World War Adjusted Compensation Act. Each veteran was to receive a dollar for each day of domestic service, up to a maximum of $500, and $1.25 for each day of overseas service, up to a maximum of $625. (74)

In order to prevent an immediate strain on its funds, the Government decided to pay the money over a 20 year period. During the Great Depression, many of these veterans found it difficult to find work. An increasing number came to the conclusion that the money would be more useful to them in this time of need than when the bonus was due. As Jim Sheridan pointed out: "The soldiers were walking the streets, the fellas who had fought for democracy in Germany. They thought they should get the bonus right then and there because they needed the money." (75)

In 1932 John Patman of Texas, introduced the Veteran's Bonus Bill which mandated the immediate cash payment of the endowment promised to the men who fought in the war. Although there was congressional support for the immediate redemption of the military service certificates, President Hoover opposed such action claiming that the government would have to increase taxes to cover the costs of the payout. (76)

In a letter to Reed Smoot, the senator from Utah, Hoover explained: "The proposal is to authorize loans upon these certificates up to 50% of their face value. As the face value is about $3,423,000,000, loans at 50% thus create a potential liability for the Government of about $1,172,000,000, and, less the loans made under the original Act, the total cash which might be required to be raised by the Treasury is about $1,280,000,000 if all should apply. The Administrator of Veterans' Affairs informs me by the attached letter that he estimates that if present conditions continue, then 75% of the veterans may be expected to claim the loans, or a sum of approximately $1,000,000,000 will need to be raised by the Treasury." (77)

In May 1932, 10,000 of these ex-soldiers marched on Washington in an attempt to persuade Congress to pass the Patman Bill. When they arrived in the capital the Bonus Army camped at Anacostia Flats, an area that had formerly been used as an army recruiting centre. They built temporary homes on the site and threatened to stay there until they received payment of money granted to them by Congress. It was clear that the veteran camp was a source of great embarrassment to Hoover and provided further proof of the government's callous unconcern for the plight of the people." (78)

John Dos Passos interviewed some of the men and reported on the issue for the The New Republic : "They... needed their bonus now; 1945 would be too late, only buy wreaths for their tombstones. They figured out, too, that the bonus paid now would tend to liven up business, particularly the retail business in small towns; might be just enough to tide them over till things picked up." Unable to afford the travel costs they hitchhiked and rode free on freight trains so they could go to Washington. (79)

Malcolm Cowley pointed out: "They arrived by hundreds or thousands every day in June. Ten thousand were camped on marshy ground across the Anacostia River, and ten thousand others occupied a number of half-demolished buildings between the Capitol and the White House. They organized themselves by states and companies and chose a commander named Walter W. Waters, an ex-sergeant from Portland. Oregon, who promptly acquired an aide-de-camp and a pair of highly polished leather puttees. Meanwhile the veterans were listening to speakers of all political complexions, as the Russian soldiers had done in 1917. Many radicals and some conservatives thought that the Bonus Army was creating a revolutionary situation of an almost classical type." (80)

It is estimated that by June 1932, there were 20,000 men living in the camp. President Herbert Hoover refused to meet with the leaders of the Bonus Army and ordered the gates of the White House chained shut. Police Chief Pelham Glassford did his utmost to provide tents and bedding for the veterans, furnished medicine, and assisted with food and sanitation. "The men were camped illegally, but Glassford (who had been the youngest brigadier general with the AEF in France) choose to treat them simply as old soldiers who had fallen on old times who had fallen on hard times. He resisted efforts to use force to dislodge them." (81)

On 15th June the House of Representatives passed the Bonus Bill by 209-176. Two days later the Senate defeated it 62-18. The veterans were now ordered to leave the city. According to the authorities some 5,000 people did leave the camp. Hoover claimed that "an examination of a large number of names discloses the fact that a considerable part of those remaining are not veterans; many are communists and persons with criminal records." (82)

The vast majority of the people in the camp refused to move. Secretary of War, Patrick J. Hurley, told Hoover that the country faced the possibility of a Communist uprising of vast proportions and talked about the need to impose martial law. The District of Columbia commissioners, on the suggestion of President Hoover, ordered Glassford to clear the area where the veterans were squatting. More controversially, he also instructed the armed forces to become involved in this action. (83)

On 28th July, General Douglas MacArthur and assisted by Major George S. Patton, used soldiers from the 3rd Cavalry Regiment and the 16th Infantry, supported by tanks and machine guns, to clear the area. After a tear gas barrage the cavalry swept the camp, followed by infantrymen, who systematically set fire to the veterans' tents and temporary buildings to stop the men returning. MacArthur, controversially used tanks, four troops of cavalry with drawn sabers, and infantry with fixed bayonets, on the ex-serviceman. He justified his attack by claiming the "mob" was animated by the "essence of revolution". (84)

William E. Leuchtenburg has argued: "Far from being a menacing band of revolutionaries, the Bonus Army was a whipped, melancholy group of men trying to hold themselves together with their spirit was gone. The Communist faction had to be protected from other bonus marchers who threatened physical violence." (85) Irving Bernstein has admitted that there were some criminals in the group, but the record for serious crime in the government of President Harding was proportionately higher than in the Bonus Army. (86)

During the operation two of the men, William Hushka and Eric Carlson, were killed. Time Magazine reported that: "When war came in 1917 William Hushka, 22-year-old Lithuanian, sold his St. Louis butcher shop, gave the proceeds to his wife, joined the Army. He was sent to Camp Funston, Kansas where he was naturalized. Honorably discharged in 1919, he drifted to Chicago, worked as a butcher, seemed unable to hold a steady job. His wife divorced him, kept his small daughter. Long jobless, in June he joined a band of veterans marching to Washington to fuse with the Bonus Expeditionary Force. 'I might as well starve there as here', he told his brother. He took part in the demonstration at the Capital the day Congress adjourned without voting immediate cashing of the bonus. Last week William Hushka's Bonus for $528 suddenly became payable in full when a police bullet drilled him dead in the worst public disorder the capital has known in years." (87)

President Hoover released a statement explaining his actions against the Bonus Army: "For some days police authorities and Treasury officials have been endeavoring to persuade the so-called bonus marchers to evacuate certain buildings which they were occupying without permission... This morning the occupants of these buildings were notified to evacuate and at the request of the police did evacuate the buildings concerned. Thereafter, however, several thousand men from different camps marched in and attacked the police with brickbats and otherwise injured several policemen, one probably fatally... An examination of a large number of names discloses the fact that a considerable part of those remaining are not veterans; many are communists and persons with criminal records." (88)

Some newspapers praised President Hoover for acting decisively, however, most were highly critical of what he had done. The The New York Times, devoted its first three pages to the coverage, including a full page of photographs showing the veterans being attacked. The Washington Daily News stated: "The mightiest government in the world chasing unarmed men, women and children with Army tanks. If the Army must be called out to make war on unarmed citizens, this is no longer America. (89)

1932 Presidential Election

Franklin D. Roosevelt was selected as the Democratic Party candidate for the 1932 Presidential Election. One commentator, William E. Leuchtenburg, summed up the situation that the Democratic Party found itself in: "Liberal Democrats were somewhat uneasy about Roosevelt's reputation as a trimmer, and disturbed by the vagueness of his formulas for recovery, but no other serious candidate had such good claims on progressive support. as governor of New York, he had created the first comprehensive system of unemployment relief, sponsored an extensive program for industrial welfare, and won western progressives by expanding the work Al Smith had begun in conservation and public power." (90)

In his acceptance speech Roosevelt argued: "Yes, the people of this country want a genuine choice this year, not a choice between two names for the same reactionary doctrine. Ours must be a party of liberal thought, of planned action, of enlightened international outlook, and of the greatest good to the greatest number of our citizens.... Let us all here assembled constitute ourselves prophets of a new order of competence and of courage. This is more than a political campaign; it is a call to arms. Give me your help, not to win votes alone, but to win in this crusade to restore America to its own people." (91)

Roosevelt's campaign did little to reassure critics who thought him a vacillating politician. For example, he attacked the Hoover administration because it was "committed to the idea that we ought to centre control of everything in Washington as rapidly as possible" but advanced policies which would greatly extend the power of the national government. He said he would initiate a far-reaching plan to help the farmer; but he would do it in such a way that it would not "cost the Government any money". (92)

In one speech he made in Sioux City, Roosevelt argued that he would cut government spending by 25 per cent: "I accuse the present Administration of being the greatest spending Administration in peace times in all our history. It is an Administration that has piled bureau on bureau, commission on commission, and has failed to anticipate the dire and the reduced earning power of the people." (93) One of Roosevelt's supporters, Marriner Eccles, admitted: "Given later developments, the campaign speeches often read like a giant misprint, in which Roosevelt and Hoover speak each other's lines." (94)

There was a general agreement that Hoover ran a very bad campaign. Several leading Republican politicians, on the left of the party, including Robert LaFollette Jr of Wisconsin, Hiram Johnson of California, George Norris of Nebraska, Bronson Cutting of New Mexico and Smith Wildman Brookhart of Iowa, supported Roosevelt. Jonathan Bourne of Oregon stated: "I think Hoover is the most pitiful failure we have ever had in the White House." (95)

William E. Leuchtenburg pointed out: "If Roosevelt's program lacked substance, his blithe spirit - his infectious smile, his warm, mellow voice, his obvious ease with crowds - contrasted sharply with Hoover's glumness. While Roosevelt reflected the joy of a campaigner winging to victory. Hoover projected defeat. From the onset of the depression, he had approached problems with a relentless pessimism... A man of impressive accomplishments, he had little understanding of the nuances of the art of governing." (96)

Franklin D. Roosevelt made twenty-seven major addresses during the six month campaign, each devoted to a single subject. He spoke briefly on thirty-two additional occasions, usually at whistle-stops or impromptu gatherings to which he was invited. Herbert Hoover, by contrast, made only ten speeches, all of which were delivered during the closing weeks of the campaign. (97)

At a meeting in Detroit, President Hoover told the audience, "I wish to present to you the evidence that the measures and the policies of the Republican administration are winning this major battle for recovery. And we are taking care of distress in the meantime. It can be demonstrated that the tide has turned and the gigantic forces of depression are today in retreat." (98) The crowd responded with the cry: "Down with Hoover, slayer of veterans". According to one observer: "When he got up to speak, his face was ashen, his hands trembled. Toward the end, Hoover was a pathetic figure, a weary, beaten man, often jeered by crowds as a President had never been jeered before." (99)

The British film-star, Charlie Chaplin, took a keen interest in the election and later commented: "The lugubrious Hoover sat and sulked, because his disastrous economic sophistry of allocating money at the top in the belief that it would percolate down to the common people had failed. And amidst all this tragedy he ranted in the election campaign that if Franklin Roosevelt got into office the very foundations of the American system - not an infallible system at that moment - would be imperilled." (100)

On 31st October, 1932, in a speech in New York City Hoover attempted to show the American public had a clear choice in the election: "This campaign is more than a contest between two men. It is more than a contest between two parties. It is a contest between two philosophies of government. We are told by the opposition that we must have a change, that we must have a new deal.... This question is the basis upon which our opponents are appealing to the people in their fear and their distress. They are proposing changes and so-called new deals which would destroy the very foundations of the American system of life."

Hoover went on to argue: "The proposals of our opponents will endanger or destroy our system. I especially emphasize that promise to promote 'employment for all surplus labour at all times.' At first I could not believe that anyone would be so cruel as to hold out hope so absolutely impossible of realization to these 10,000,000 who are unemployed. And I protest against such frivolous promises being held out to a suffering people. If it were possible to give this employment to 10,000,000 people by the Government, it would cost upwards of $9,000,000,000 a year. It would pull down the employment of those who are still at work by the high taxes and the demoralization of credit upon which their employment is dependent. It would mean the growth of a fearful bureaucracy which, once established, could never be dislodged." (101)

Roosevelt heard Hoover's speech on the radio before appearing in Boston that night: "Once more he warned the people against changing - against a new deal - stating that it would mean changing the fundamental principles of America, what he called the sound principles that have been so long believed in in this country. My friends, my New Deal does not aim to change those principles. Secure in their undying belief in their great tradition and in the sanctity of a free ballot, the people of this country - the employed, the partially employed and the unemployed, those who are fortunate enough to retain some of the means of economic well-being, and those from whom these cruel conditions have taken everything - have stood with patience and fortitude in the face of adversity."

Roosevelt highlighted the plight of the unemployed: "There they stand. And they stand peacefully, even when they stand in the breadline. Their complaints are not mingled with threats. They are willing to listen to reason at all times. Throughout this great crisis the stricken army of the unemployed has been patient, law-abiding, orderly, because it is hopeful. But, the party that claims as its guiding tradition the patient and generous spirit of the immortal Abraham Lincoln, when confronted by an opposition which has given to this Nation an orderly and constructive campaign for the past four months, has descended to an outpouring of misstatements, threats and intimidation. The Administration attempts to undermine reason through fear by telling us that the world will come to an end on November 8th if it is not returned to power for four years more. Once more it is a leadership that is bankrupt, not only in ideals but in ideas." (102)

During the campaign Herbert Hoover had to have a heavy police escort to protect him from the angry crowds. He became very unpopular when he told one of the most influential journalists in Washington, Raymond Clapper: "Nobody is actually starving. The hobos, for example, are better fed than they have ever been." In another interview he attributed the high unemployment rate to the fact that "many people have left their jobs for the more profitable one of selling apples." (103)

Three days before the election he claimed that Roosevelt's policies could be compared to those of Joseph Stalin. He suggested that his opponent had "the same philosophy of government which has poisoned all of Europe... the fumes of the witch's cauldron which boiled in Russia." He accused the Democrats of being "the party of the mob". Hoover then added: "Thank God, we still have a government in Washington that knows how to deal with the mob." (104)

The turnout, almost 40 million, was the largest in American history. Roosevelt received 22,825,016 votes to Hoover's 15,758,397. With a 472-59 margin in the Electoral College, he captured every state south and west of Pennsylvania. Roosevelt carried more counties than a presidential candidate had ever won before, including 282 that had never gone Democratic. Of the forty states in Hoover's victory coalition four years before, the President held but six. Hoover received 6 million fewer votes than he had in 1928. The Democrats gained ninety seats in the House of Representatives to give them a large majority (310-117) and won control of the Senate (60-36). Only one previous Republican candidate, William Howard Taft, had done as badly as Hoover. (105)

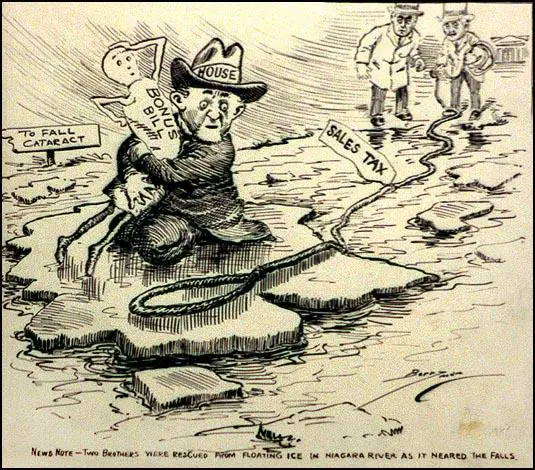

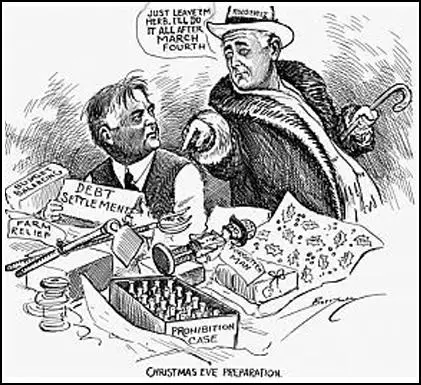

all after March 4th." Cliff Berryman, Washington Evening Star (December, 1932)

Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected on 8th November, 1932, but the inauguration was not until 4th March, 1933. While he waited to take power, the economic situation became worse. Three years of depression had cut national income in half. Five thousand bank failures had wiped out 9 million savings accounts. By the end of 1932, 15 million workers, one out of every three, had lost their jobs. When the Soviet Union's trade office in New York issued a call for 6,000 skilled workers to go to Russia, more than 100,000 applied. (106)

Edmund Wilson published an article in The New Republic just before Roosevelt took office: "There is not a garbage-dump in Chicago which is not diligently haunted by the hungry. Last summer, the hot weather when the smell was sickening and the flies were thick, there were a hundred people a day coming to one of the dumps... a widow who used to do housework and laundry, but now had no work at all, fed herself and her fourteen-year-old son on garbage. Before she picked up the meat, she would always take off her glasses so that she couldn't see the maggots." (107)

Final Years

Out of power, Hoover opposed Roosevelt's New Deal programme. He told the New York Times on 31st October, 1936: "I rejected the schemes of economic planning to regiment and coerce the farmer. That was born of a Roman despot 1400 years ago and grew into the AAA. I refused national plans to put government into business in competition with its citizens. That was born of Karl Marx. I vetoed the idea of recovery through stupendous spending to prime the pump. That was born of a British Professor (John Maynard Keynes)." (108)

Hoover feared that the country had surrendered its "freedom of mind and spirit" to the New Deal. He described the National Recovery Administration and Agricultural Adjustment Administration as "fascistic," and the Banking Act as a "move to gigantic socialism." (109) Hoover travelled around the country "seeking vindication for what he believed had been a singularly successful four years in the White House". However, he was so unpopular that his opinions were rejected by a public who continued to support the policies of Franklin D. Roosevelt. "Hoover's message of retrenchment, the gold standard, and a balanced budget fell on deaf ears. Most Republican politicians shunned the former president's embrace, certain it meant electoral defeat." (110)

In 1936, Hoover attempted to obtain the Republican presidential nomination. However, Alf Landon was selected instead. In 1938 Hoover visited ten European countries in 30 days and spoke to several leading politicians, including Adolf Hitler. Despite the Nazi government's aggressive foreign policy, Hoover stated on his return: "I do not believe a widespread war is at all probable in the near future. There is a general realization everywhere ... that civilization as we know it cannot survive another great war." (111)

At the 1940 Republican National Convention, Hoover again hoped for the presidential nomination, and was dismayed when it went to the internationalist Wendell Willkie. He attacked Willkie for supporting Roosevelt's foreign policy and organized a statement signed by eminent Republicans that stated they wanted Britain and her allies to win but that "in giving generous aid to these democracies at our seaboard we have gone as far as is consistent either with law, with sentiment, or with security... Freedom for America does not depend on the outcome of struggles for material power among other nations." (112)

Hoover was strongly opposed to any alliance with the Soviet Union if the United States went to war with Germany: " If we go further and join the war and we win, then we have won for Stalin the grip of communism on Russia.... Again I say, if we join the war and Stalin wins, we have aided him to impose more communism on Europe and the world. At least we could not with such a bedfellow say to our sons that by making the supreme sacrifice, they are restoring freedom to the world. War alongside Stalin to impose freedom is more than a travesty. It is a tragedy." (113)

After the Second World War, Hoover was involved in several American relief operations in Europe. He had a reasonable relationship with Harry S. Truman, who appointed him as chairman of a commission to reorganize the executive departments. The Hoover Commission recommended changes designed to strengthen the president's ability to manage the federal government. However, he did not get on with President Dwight D. Eisenhower, because he was disappointed with his unwillingness to roll back the New Deal. (114)

Herbert Hoover died following massive internal bleeding at the age of 90 on 20th October, 1964.

Primary Sources

(1) Andrew Mellon, Taxation: the People's Business (1924)

The problem of the government is to fix rates which will bring in a maximum amount of revenue to the Treasury and at the same time bear not too heavily on the taxpayer or on business enterprises. A sound tax policy must take into consideration three factors. It must produce sufficient revenue for the government; it must lessen, so far as possible, the burden of taxation on those least able to bear it; and it must also remove those influences which might retard the continued steady development of business and industry on which, in the last analysis, so much of our prosperity depends.

Furthermore, a permanent tax system should be designed, not merely for one or two years nor for the effect it may have on any given class of taxpayers but should be worked out with regard to conditions over a long period and with a view to its ultimate effect on the prosperity of the country as a whole. These are the principles on which the Treasury's tax policy is based, and any revision of taxes which ignores these fundamental principles will prove merely a makeshift and must eventually be replaced by a system based on economic rather than political considerations.

There is no reason why the question of taxation should not be approached from a nonpartisan and business viewpoint. In recent years, in any discussion of tax revision, the question which has caused most controversy is the proposed reduction of the surtaxes. Yet recommendations for such reductions have not been confined to either Republican or Democratic administrations. My own recommendations on this subject were in line with similar ones made by Secretaries Houston and Glass, both of whom served under a Democratic President. Tax revision should never be made the football either of partisan or class politics but should be worked out by those who have made a careful study of the subject in its larger aspects and are prepared to recommend the course which, in the end, will prove for the country's best interest.

I have never viewed taxation as a means of rewarding one class of taxpayers or punishing another. If such a point of view ever controls our public policy, the traditions of freedom, justice, and equality of opportunity, which are the distinguishing characteristics of our American civilization, will have disappeared and in their place we shall have class legislation with all its attendant evils. The man who seeks to perpetuate prejudice and class hatred is doing America an ill service. In attempting to promote or to defeat legislation by arraying one class of taxpayers against another, he shows a complete misconception of those principles of equality on which the country was founded. Any man of energy and initiative in this country can get what he wants out of life. But when that initiative is crippled by legislation or by a tax system which denies him the right to receive a reasonable share of his earnings, then he will no longer exert himself and the country will be deprived of the energy on which its continued greatness depends.

This condition has already begun to make itself felt as a result of the present unsound basis of taxation. The existing tax system is an inheritance from the war. During that time the highest taxes ever levied by any country were borne uncomplainingly by the American people for the purpose of defraying the unusual and ever increasing expenses incident to the successful conduct of a great war. Normal tax rates were increased, and a system of surtaxes was evolved in order to make the man of large income pay more proportionately than the smaller taxpayer. If he had twice as much income, he paid not twice but three or four times as much tax. For a short time the surtaxes yielded a large revenue.

But since the close of the war people have come to look upon them as a business expense and have treated them accordingly by avoiding payment as much as possible. The history of taxation shows that taxes which are inherently excessive are not paid. The high rates inevitably put pressure upon the taxpayer to withdraw his capital from productive business and invest it in tax-exempt securities or to find other lawful methods of avoiding the realization of taxable income. The result is that the sources of taxation are drying up; wealth is failing to carry its share of the tax burden; and capital is being diverted into channels which yield neither revenue to the government nor profit to the people.

(2) Lincoln Steffens, Autobiography (1931)

That presidential election with Governor Smith, a Jeffersonian Democratic politician, running to defeat against Hoover, an engineer in business, seemed to mark the end of a period, my period, and perhaps of a culture, the moral culture. Hoover was the Hamiltonian, who had no democracy in him, none, neither political nor economic. He has shown no sense of the perception that privileges are a cause of our social trouble. He is a moralist in that. He believes in the ownership and management by business men of all business, including land and natural resources, transportation, power, light. Good business is all the good we need. Politics was the only evil, and he has no sense of politics. When he came home from his years and years of professional service in foreign lands, he did not know or care whether he was a Democrat or a Republican; he was a candidate and won some votes for the nomination for president at a Democratic convention. He stood four years later as the Republican candidate of and for business against an able, successful Democrat who was a philosophic, political democrat. And the people believed, as they voted, with Hoover. Food, shelter, and clothing, plus the car, the radio-prosperity interested them more than any old American principles, which were all on the Democratic side with Smith. I went through that campaign, sensitive, interested, non-partisan. What little I said was in the Jeffersonian tradition, but I was watching to report, not playing to win. I can assert that everybody was for business; even the Democrats who voted for Smith, were for good business, of course; they, too, expected Smith to carry on the good times and favor business. It seems to me that there are many more Republicans in this country than voted for Hoover, that our southern Democrats, party-bound by their traditions, are unconscious Republicans who only think that they are Democrats, who don't know that they are Republicans. In California, where I was living, there were no politics or principles at all. It was all business. In brief, that was an economic election which sent to the White House Herbert Hoover to do what he is trying to do: to represent business openly, as Coolidge and other presidents had covertly.

(3) Herbert Hoover, letter to Reed Smoot (18th February, 1931)

I have given thought to your request that I should express to you and the Senate Finance Committee my views upon the bill passed by the House of Representatives, increasing the loans to World War veterans upon the so-called bonus certificates. In view of the short time remaining in this session for its consideration I shall comply with your request.

The proposal is to authorize loans upon these certificates up to 50% of their face value. And to avoid confusion it must be understood that the “face value” is the sum payable at the end of the 20 years period (1945) being based on the additional compensation to veterans of about $1,300,000,000 granted about six years ago, plus 25% for deferment, plus 4% compound interest for the 20 year period. As the “face value” is about $3,423,000,000, loans at 50% thus create a potential liability for the Government of about $1,172,000,000, and, less the loans made under the original Act, the total cash which might be required to be raised by the Treasury is about $1,280,000,000 if all should apply. The Administrator of Veterans' Affairs informs me by the attached letter that he estimates that if present conditions continue, then 75% of the veterans may be expected to claim the loans, or a sum of approximately $1,000,000,000 will need to be raised by the Treasury.

I will not undertake to enumerate all of the grounds for objection to this proposal. There are a number of most serious objections, some of which are matters of method and some of which are matters of fundamental principle affecting the future of our country and the service men themselves.

I have supported, and the nation should maintain, the important principle that when men have been called into jeopardy of their very lives in protection of the Nation, then the Nation as a whole incurs a special obligation beyond that to any other groups of its citizens. These obligations cannot be wholly met with dollars and cents. But good faith and gratitude require that protection be given to them when in ill health, distress and in need. Over 700,000 World War Veterans or their dependents are today receiving monthly allowances for these reasons. The country should not be called upon, however, either directly or indirectly, to support or make loans to those who can by their own efforts support themselves.

By far the largest part of the huge sum proposed in this bill is to be available to those who are not in distress.

The acute depression and unemployment create a situation of unusual economic sensitiveness, much more easily disturbed at this time than in normal times by the consequences of this legislation, and such action may quite well result in a prolongation of this period of unemployment and suffering in which veterans will themselves suffer with others.

By our expansion of public construction for assistance to unemployment and other relief measures, we have imposed upon ourselves a deficit in this fiscal year of upwards of $500,000,000 which must be obtained by issue of securities to the investing public. This bill may possibly require the securing of a further billion of money likewise from the public. Beyond this, the Government is faced with a billion dollars of early maturities of outstanding debts which must be refunded aside from constant renewals of a very large amount of temporary Treasury obligations. The additional burdens of this project cannot but have damaging effect at a time when all effort should be for the rehabilitation of employment through resumption of commerce and industry.

There seems to be a misunderstanding in the proposal that the Government securities already lodged with the Treasury to the amount of over $700,000,000 as reserve against these certificates constitute available cash to meet this potential liability. The cash required by the veterans can only be secured by the sale of these securities to the public. The legislation is defective in that this $700,000,000 of Government securities is wholly inadequate to mend either a potential liability of $1,280,000,000 or approximately $1,000,000,000 estimated as possible by the Administrator of Veterans' Affairs, and provision would need to be made at once for this deficiency.

The one appealing argument for this legislation is for veterans in distress. The welfare of the veterans as a class is inseparable from that of the country. Placing a strain on the savings needed for rehabilitation of employment by a measure which calls upon the Government for a vast sum beyond the call of distress, and so adversely affecting our general situation, will in my view not only nullify the benefits to the veteran but inflict injury to the country as a whole.

(4) Herbert Hoover, statement (11th December, 1931)

In my recommendations to Congress and in the organizations created during the past few months, there is a definite program for turning the tide of deflation and starting the country upon the road to recovery. This program has been formulated after consultation with leaders of every branch of American public life, of labor, of agriculture, of commerce, and of industry. A considerable part of it depends on voluntary organization in the country. This is already in action. A part of it requires legislation. It is a non-partisan program. I am interested in its principles rather than its details. I appeal for unity of action for its consummation.

The major steps that we must take are domestic. The action needed is in the home field, and it is urgent. While reestablishment of stability abroad is helpful to us and to the world, and I am confident that it is in progress, yet we must depend on ourselves. If we devote ourselves to these urgent domestic questions we can make a very large measure of recovery irrespective of foreign influences.

That the country may get this program thoroughly in mind, I review its major parts:

1. Provision for distress among the unemployed by voluntary organization and united action of local authorities in cooperation with the President's Unemployment Relief Organization, whose appeal for organization and funds has met with a response unparalleled since the war. Almost every locality in the country has reported that it will “take care of its own.” In order to assure that there will be no failure to meet problems as they arise, the organization will continue through the winter.

2. Our employers are organized and will continue to give part-time work instead of discharging a portion of their employees. This plan is affording help to several million people who otherwise would have no resources. The government will continue to aid unemployment over the winter through the large program of Federal construction now in progress. This program represents an expenditure at a rate of over $60,000,000 a month.

3. The strengthening of the Federal Land Bank System in the interest of the farmer.

4. Assistance to homeowners, both agricultural and urban, who are in difficulties in securing renewals of mortgages by strengthening the country banks, savings banks, and building and loan associations through the creation of a system of Home Loan Discount Banks. By restoring these institutions to normal functioning, we will see a revival in employment in new construction.

5. Development of a plan to assure early distribution to depositors in closed banks, and thus relieve the stress amongst millions of smaller depositors and smaller businesses.

6. The creation for the period of the emergency of a Reconstruction Finance Corporation to furnish necessary credit otherwise unattainable under existing circumstances, and so give confidence to agriculture, to industry and to labor against further paralyzing influences and shocks, but more especially by the reopening of credit channels which will assure the maintenance and normal working of the commercial fabric.

7. Assistance to all railroads by protection from unregulated competition, and to the weaker ones by the formation of a credit pool, as authorized by the Interstate Commerce Commission, and by other measures, thus affording security to the bonds held by our insurance companies, our savings banks, and other benevolent trusts, thereby protecting the interest of every family and promoting the recuperation of the railways.

8. The revision of our banking laws so as better to safeguard the depositors.

9. The safeguarding and support of banks through the National Credit Association, which has already given great confidence to bankers and extended their ability to make loans to commerce and industry.

10. The maintenance of the public finance on a sound basis. (a) By drastic economy. (b) Resolute opposition to the enlargement of Federal expenditure until recovery. (c) A temporary increase in taxation, so distributed that the burden may be borne in proportion to ability to pay amongst all groups and in such a fashion as not to retard recovery.

The maintenance of the American system of individual initiative and individual and community responsibility.

The broad purpose of this program is to restore the old job instead of creating a made job, to help the worker at the desk as well as the bench, to restore their buying power for the farmers' products - in fact, turn the processes of liquidation and deflation and start the country forward all along the line.

This program will affect favorably every man, woman, and child - not a special class or any group. One of its purposes is to start the flow of credit now impeded by fear and uncertainty, to the detriment of every manufacturer, business man and farmer. To reestablish normal functioning is the need of the hour.

(5) Herbert Hoover, statement (28th July, 1932)

For some days police authorities and Treasury officials have been endeavoring to persuade the so-called bonus marchers to evacuate certain buildings which they were occupying without permission. These buildings are on sites where Government construction is in progress and their demolition was necessary in order to extend employment in the District to carry forward the Government's construction program.

This morning the occupants of these buildings were notified to evacuate and at the request of the police did evacuate the buildings concerned. Thereafter, however, several thousand men from different camps marched in and attacked the police with brickbats and otherwise injured several policemen, one probably fatally.

I have received the attached letter from the Commissioners of the District of Columbia stating that they can no longer preserve law and order in the District.

In order to put an end to this rioting and defiance of civil authority, I have asked the Army to assist the District authorities to restore order.

Congress made provision for the return home of the so-called bonus marchers who have for many weeks been given every opportunity of free assembly, free speech and free petition to the Congress. Some 5,000 took advantage of this arrangement and have returned to their homes. An examination of a large number of names discloses the fact that a considerable part of those remaining are not veterans; many are communists and persons with criminal records.

The veterans amongst these numbers are no doubt aware of the character of their companions and are being led into violence which no government can tolerate.

(6) Herbert Hoover, statement (29th July, 1932)

A challenge to the authority of the United States Government has been met, swiftly and firmly.

After months of patient indulgence, the Government met overt lawlessness as it always must be met if the cherished processes of self-government are to be preserved. We cannot tolerate the abuse of Constitutional rights by those who would destroy all government, no matter who they may be. Government cannot be coerced by mob rule.