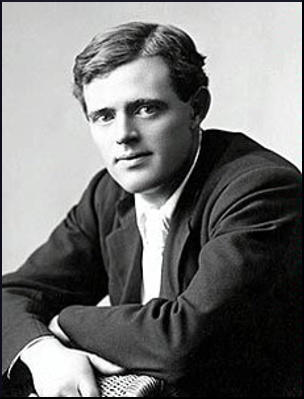

Jack London

Jack London was born in San Francisco on 12th January, 1876. His mother, Flora Wellman, was unmarried, but lived with William Chaney, an itinerant astrologer. The San Francisco Chronicle reported that Chaney left her before Jack was born: "He (Chaney) told the poor woman that he had sold the furnishings (for which she had helped to pay) and it was useless to think of her remaining there any longer. He then left her, and shortly afterwards she made her first attempt at suicide, following it by the effort to kill herself with a pistol on the following morning... Failing in both endeavours, Mrs Chaney was removed in a half-insane condition from Dr Ruttley's on Mission Street to the house of a friend, where she still remains, somewhat pacified and in a mental condition indicating that she will not again attempt self-destruction. The story given here is the lady's own, as filtered through her near associates." (1)

William Chaney later denied he was the boy's father. In May 1897 Chaney told Jack "I was never married to Flora Wellman but she lived with me from June 11, 1874, until June 3, 1875. I was impotent at that time, the result of hardship, privation, and too much brain work. Therefore I cannot be your father, nor am I sure who your father is." (2) The birth of "nearly killed" his mother and for the first eight months he was brought up by a wet-nurse, a local black woman, Virginia Prentiss.

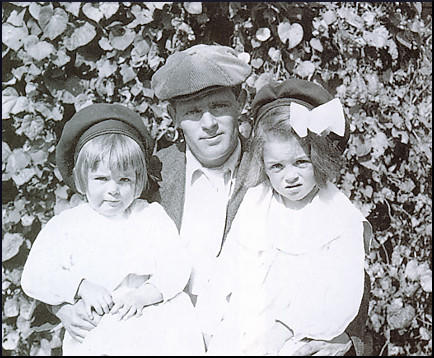

A few months after Jack's birth, Flora met and quickly married a middle-aged American Civil War veteran, John London, who had two young daughters, Eliza and Ida. Flora still had problems coping after Jack returned to the family home and it was his eight-year old, step-sister, Eliza, who took on the duties of a mother: "Elizia would continue to act as a surrogate mother for the rest of Jack's life, and would become the one woman he would trust and love more than any other. It was Eliza, not Flora, who read to him at bedtime." (3)

The family moved to Oakland where John London acquired a couple of acres and started a market garden. He was very successful with this venture and he later moved to a larger property in San Mateo County. His success as a smallholder continued and eventually he purchased an eighty-seven-acre ranch in Livermore. It was a happy period in Jack's life and enjoyed being a hard-working farm-boy. However, he was devastated in 1884, when sixteen-year old Eliza, eloped with a man old enough to be her father. A few months later an epidemic killed off London's chickens. Other economic setbacks meant that London could not pay his mortgage repayments and the family was forced to return to Oakland.

Jack London: Factory Worker

Jack London left school at fourteen because his family could not afford to put him through high school and he began work at Hickmott's, the local canning factory. He later wrote in an autobiographical short-story: "In the factory quarter, doors were opening everywhere, and he was soon one of a multitude that pressed onward through the dark. As he entered the factory gate the whistle blew again. He glanced at the east. Across a ragged sky-line of housetops a pale light was beginning to creep. This much he saw of the day as he turned his back upon it and joined his work gang.... The procession of the days he never saw. The nights he swept away in a twitching consciousness. The rest of the time he worked, and his consciousness was machine consciousness. Outside this his mind was a blank." (4)

London spent his free time in saloons along the San Francisco waterfront and was often drunk. He discovered that drinking dealt with his sense of isolation and enjoyed listening to seamen telling stories of life as "whalers, sealers, harpooners, every one an expert in killing." (5). London later claimed: "In the saloons life was different. Men talked with great voices, laughed great laughs and there was an atmosphere of greatness." (6)

While drinking in Johnny Heinold's saloon London heard about the large sums people could make by becoming oyster pirates. These men stole from private beds and sold the oysters for enormous profits. He borrowed $300 and purchased a sloop, the Razzle Dazzle. One night's work could earn London $25, far more than he would have earned in a month at Hickmott's Cannery. However, as Alex Kershaw, the author of Jack London: A Life (1997), has pointed out: "The reality of Jack's new profession was that death always stalked close by. Every night, he had to navigate without lights, his oarlocks muffled in case he alerted armed guards protecting the oyster beds. Often, his only guidance was gunfire lighting up the sky. Life was even cheaper on San Francisco's Barbary Coast and Oakland's estuary, where Jack spent afternoons drinking before the night's adventure, and where his associates thoght nothing of stabbing a man in the back for a sack of rotting shellfish." (7) His three months of making good money came to an end when his sloop was destroyed by fire.

In 1892 he joined the crew of the Sophie Sutherland that was heading to the Bering Sea to kill seals. London later recalled that the boat was a floating slaughter house, her decks "covered with hides and bodies, slippery with fat and blood, the scuppers running red, masts, ropes, and rails splattered with sanguinary colour; and the men, like butchers with ripping and flensing knives, removing the skins from the pretty creatures they had killed." (8)

Jack London arrived back in San Francisco on 26th August 1893. The voyage had lasted almost eight months. While he had been away, one of his best friends, Scratch Nelson, had been killed in a gun-fight with the police. Many of those still alive were imprisoned in San Quentin. London decided to change his way of life: "My mother said I had sown my wild oats and it was time I settled down to a regular job. Also, the family needed the money. So I got a job in the jute mills - a ten-hour day at ten cents an hour. Despite my increase in strength and general efficiency, I was receiving no more than when I worked in the cannery several years before." (9)

Political Development

London had a great love of books and he decided that he would now spend more time in Oakland Library. His reading included books by Rudyard Kipling, Gustave Flaubert, Leo Tolstoy and Herman Melville. London also began writing short-stories. When the San Francisco Morning Call announced a competition for young writers, the 17 year old London submitted Typhoon off the Coast of Japan. It won first prize of $25, with second and third prizes going to men in their early twenties studying at the University of California and at Stanford University.

London was also developing an interest in politics. He read about Eugene Debs being imprisoned for leading a rail-workers' strike in Chicago. He decided to join a march on Washington led by Jacob S. Coxley. The plan was to demand that Congress allocate funds to create jobs for the unemployed. In Oakland a young printer, Charles T. Kelly, assembled a detachment of two thousand men who would travel to the capital in box-cars provided free of charge by railroad companies anxious to shunt them east and thereby rid the region of potential trouble-makers. When the men reached Des Moines, Iowa, the railroad company decided the journey had come to an end.

London eventually jumped onto a freight train headed for Niagara Falls. However, soon after arriving he was arrested and charged with vagrancy. Found guilty he was sentenced to thirty days hard labour and taken to Erie County Penitentiary. London was shocked by life in the prison. He later wrote that the prison was "filled with the ruck and the filth, the scum and the dregs of society - hereditary inefficients, degenerates, wrecks, lunatics, addled intelligences, epileptics, monsters, weaklings, in short a very nightmare of humanity."

Jack London & Karl Marx

At Oakland Library London found a copy of The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He wrote in his notebook: "The whole history of mankind has been a history of contests between exploiting and exploited; a history of these class struggles shows the evolution of man; with the coming of industrialism and concentrated capital a stage has been reached whereby the exploited cannot attain its emancipation from the ruling class without once and for all emancipating society at large from all future exploitation, oppression, class distinctions and class struggles." (11)

London also read Looking Backward, a novel written by Edward Bellamy. Published in 1888 and set in Boston, the book's hero, Julian West, falls into a hypnotic sleep and wakes in the year 2000, to find he is living in a socialist utopia where people co-operate rather than compete. The novel was highly successful and sold over 1,000,000 copies. It was the third largest bestseller of its time, after Uncle Tom's Cabin and Ben-Hur and it is claimed that the book converted a large number of people to socialism.

Jack London wrote that he had "began a frantic pursuit of knowledge." London discovered that "other and greater minds, before I was born, had worked out all that I thought, and a vast deal more. I discovered that I was a Socialist." He joined the local Socialist Labor Party (SLP) in Oakland and made speeches on street-corners. On 16th February 1896, the San Francisco Chronicle reported: "Jack London, who is known as the boy socialist of Oakland, is holding forth nightly to the crowds that throng City Hall Park. There are other speakers in plenty, but London always gets the biggest crowd and the most respectful attention. the young man is a pleasant speaker, more earnest than eloquent, and while he is a broad socialist in every way, he is not an anarchist." (12)

In 1896 London became friends with one of the women at the SLP, Mabel Applegarth. She was studying English at the University of California. London was besotted with twenty-one year old Mabel and described her as having "spiritual blue eyes" and having a "mass of golden hair". According to Alex Kershaw, the author of Jack London: A Life (1997): "Her porcelain skin, refined diction and ability to quote whole sonnets from the Romantic poets made her seem a goddess to him... In Mabel, Jack had found a member of the opposite sex, the first he had met, who was both attractive and intellectual, who could understand, if not where he had come from, at least where he wanted to go." (13)

Mabel encouraged London to become a student at Berkeley. After three months of intense craming, London sat the three-day entrance exams on 10th August 1896. He passed with distinction and entered the university that autumn with the main intention of learning how to write. A fellow student, James M. Hopper, became one of his new friends: "His clothes were floppy and careless; the forecastle had left a suspicion of a roll in his broad shoulders; he was a strange combination of Scandinavian sailor and Greek god, made altogether boyish and lovable by the lack of two front teeth, lost cheerfully somewhere in a fight... He was going to take all the courses in the natural sciences, many in history, and bite a respectable chunk out of the philosophies." (14)

Klondike Gold Rush

In July, 1897, Jack London read of gold being found in the Klondike region of the Yukon in north-western Canada. This created a "stampede of prospectors". London approached local newspapers with the idea of reporting on the Klondike Gold Rush. The idea was rejected but London was determined to go and after borrowing money from step-sister Eliza, he began making preparations to leave university.

Mabel Applegarth was horrified by this decision. Her mother wrote a letter to him concerning his proposed trip: "Oh, dear John, do be persuaded to give up the idea, for we feel certain that you are going to meet your death, and we shall never see you again... Your Father and Mother must be nearly crazed over it. Now, even at the eleventh hour, dear John, do change your mind and stay." (15)

Jack London refused to abandon his plans and after a long "back-breaking" journey reached Dawson City. The US Marshall trying to control the city, Frank Canton, described it as "a wild, picturesque, lawless mining camp. The like had never been known, never would be seen again. It was a picture of blood and glittering gold-dust, starvation and death ... If a man could not get the woman he wanted, the man who did get her had to fight for her life." (16)

Later he described a dance he attended in Dawson City: "The crowded room was thick with tobacco smoke. A hundred men, dressed in furs and warm-coloured wools, lined the walls and looked on. But the mumble of their general conversation destroyed the spectacular feature of the scene and gave to it the geniality of common comradeship... Kerosene lamps and tallow candles glimmered feebly in the murky atmosphere, while large stoves roared their red-hot and white-hot cheer. On the floor a score of couples pulsed rhythmically to the swinging waltz-time music. The men wore their wolf and beaver skin caps, with the grey-tasselled ear-flaps flying free, while on their feet were the moose-skin moccasins and walrus-hide of the north." (17)

It has been estimated that over $60 million was spent by prospectors during the Klondike Gold Rush but gold valued at $10 million was extracted from the ground. Jack London was one of those who arrived back home broke (he claimed he found only $4.50 in gold dust). However, the experience had provided him with some great experiences to write about: "I never realised a cent from any properties I had an interest in up there. Still, I have been managing to pan out a living ever since on the strength of the trip." (18)

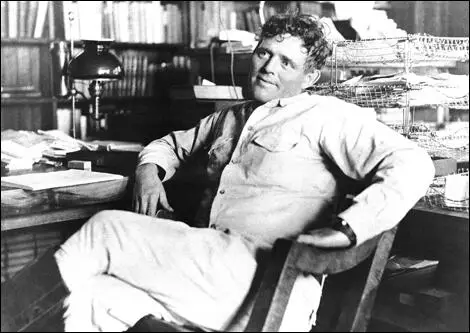

Early Writing Career

Jack London was convinced that he now had the material for a successful writing career. As Alex Kershaw, the author of Jack London: A Life (1997) has pointed out: "Sheer discipline would be his lifeline. He would also adopt Kipling's work ethic. Work! Work! And so he established a routine, which was to last a lifetime of writing a thousand words a day. If he fell behind his daily quota, he compensated the following morning." (19)

However, his first stories that he produced were rejected by magazine publishers. It took him six months before the highly regarded Overland Monthly, accepted the first of Jack London's Klondike stories, To The Man on Trail. This was followed by The White Silence that appeared in the February 1899 edition. It received a great reviews and established London was one of the country's most promising writers. George Hamlin Fitch, literary critic of the San Francisco Chronicle, concluded: "I would rather have written The White Silence than anything that has appeared in fiction in the last ten years." (20) London was very disappointed that the magazine only paid him $7.50 for the story.

London now sent his short-stories to Atlantic Monthly, the most important literary magazine in New York City. In January 1900 they paid him $120 for An Odyssey of the North. This brought him to the attention of the publishers Houghton Mifflin, who suggested the idea of collecting his Alaska tales in book form. The result was The Son of the Wolf, which appeared in April 1900. Cornelia Atwood Pratt gave the book a great review: "His work is as discriminating as it is powerful. It has grace as well as terseness, and it makes the reader hopeful that the days of the giants are not yet gone by."

Later that year Jack London won a short-story competition sponsored by Cosmopolitan. The magazine was so impressed that they offered him the post of assistant editor and staff writer. He rejected the idea of being employed by a magazine. He told his friend, Cloudesley Johns: "I shall not accept it. I do not wish to be bound... I want to be free, to write what delights me. No office work for me; no routine; no doing this set task and that set task. No man over me." (21)

Jack London and Women

Jack London had enjoyed a close relationship with Mabel Applegarth but he wrote to Johns that he felt he had outgrown her: "It was a great love, at the time, I mistook the moment for the eternal... Time passed. I awoke, frightened, and found myself judging. She was very small. The positive virtues were hers, and likewise the negative vices. She was pure, honest, true, sincere, everything. But she was small. Her virtues led her nowhere. Works? She had none. Her culture was a surface smear, her deepest depth a singing shallow. Do you understand? Can I explain further? I awoke, and judged, and my puppy love was over." (22)

In December 1899 London met the 20 year-old Anna Strunsky. A mutual friend, Joseph Noel, described her as "a pretty little ingenue who played the part of a Stanford University intellectual to perfection. She had soft brown eyes, a kindly smile and a throaty little voice that did things to your spine." (23) She later recalled: "Objectively, I confronted a young man of about twenty-two, and saw a pale face illumined by large, blue eyes fringed with dark lashes, and a beautiful mouth which, opening in its ready laugh, revealed an absence of front teeth, adding to the boyishness of his appearance. The brow, the nose, the contour of the cheeks, the massive throat, were Greek. His form gave an impression of grace and athletic strength, though he was a little under the American, or rather Californian, average in height. He was dressed in gray, and was wearing the soft white shirt and collar which he had already adopted."

London told her he was reading Seven Seas by Rudyard Kipling. "The Anglo-Saxons were the salt of the earth, he declared. He forgave Kipling his imperialism because he wrote of the poor, the ignorant, the submerged, of the soldier and sailor in their own language." Anna was a socialist and was critical of his desire to become rich. "I looked for the Social Democrat, the Revolutionist, the moral and romantic idealist; I sought the Poet. Exploring his personality was like exploring mountains and the valleys which stretched between troubled my heart ... He was a Socialist, but he wanted to beat the Capitalist at his own game. To succeed in doing this, he thought, was in itself a service to the Cause; to show them that Socialists were not derelicts and failures had certain propaganda value." (24)

Jack was in love with Anna but did not feel she was the right woman to marry. It has been claimed by one biographer that London divided women into two groups. They were either "wonderful and unmoral and filled with life to the brim", or offering the promise of being "the perfect mother, made pre-eminently to know the clasp of the child". Another biographer, Rose Wilder Lane, claimed he wanted a mother to "seven sturdy Anglo-Saxon sons". (25) Jack knew such a woman, Bessie Maddern, like Strunsky, a member of the Socialist Labor Party. The journalist, Joseph Noel, described Bess was "slender and, no doubt because she had her hair in the Pompadour mode, looked nearly as tall as Jack. Her face, strong, well-modelled, was enhanced by grey eyes fringed by chorus-girl lashes. When she smiled she was at her best. The surroundings were brightened." (26) Although he told Bessie he did not love her, he married her on 7th April 1900. After a brief honeymoon, husband and wife moved into a large house at 1130 East Fifteenth Street in Oakland.

Jack London continued to spend time with Anna Strunsky. On one occasion Bessie come across Anna sitting on Jack's knee in his study. Irving Stone, the author of Sailor on Horseback (1938) quoted London as saying: "It was her intellect that fascinated me, not her womanhood. Primarily she was intellect and genius. I love to seek and delve in human souls, and she was an exhaustless mine to me. Protean, I called her. My term for her of intimacy and endearment was what? A term that was intellectual, that described her mind." (27)

Socialist Candidate for Mayor

Jack London continued to be politically active and made public speeches on the merits of revolutionary socialism. He told his friend, Cloudesley Johns: "I should like to have socialism.... yet I know that socialism is not the very next step; I know that capitalism must live its life first, that the world must be exploited to the utmost first; that first must intervene a struggle for life among the nations, severer, more widespread than before. I should much prefer to wake tomorrow in a smoothly-running socialist state but I know I shall not; I know it cannot come that way. I know that the child must go through the child's sickness before it becomes a man. So, always remember that I speak of things that are; not of things that should be." (28)

In 1901 he agreed to exploit his growing fame by becoming the socialist candidate for Mayor of Oakland.The San Francisco Evening Post reported on 26th January, 1901: "Jack London is announced as a candidate for Mayor of Oakland... I don't know what a socialist is, but if it is anything like some of Jack London's stories, it must be something awful. I understand that as soon as Jack London is elected Mayor of Oakland by the Social Democrats the name of the place will be changed. The Social Democrats, however, have not yet decided whether they will call it London or Jacktown." (29) London received just 246 votes (the winning candidate obtained 2,548). However, he was happy that he was able to bring the principles of socialism to a wider audience.

A Daughter of the Snows

The New York City publisher, Samuel McClure offered to publish virtually anything Jack London produced. To obtain his services he agreed to pay him a retainer of $100. However, he was disappointed with his first novel, A Daughter of the Snows, and refused to serialize it in McClure's Magazine. McClure sold it to another publisher for $750 and it was published in 1902. Alex Kershaw argues that "A Daughter of the Snows was a badly executed jumble of his current intellectual confusions. Its disorganised melodrama and unconvincing characters failed to impress." (30)

The best review of The Daughter of the Snows came from Julian Hawthorne, the son of Nathaniel Hawthorne: "He (Jack London) knows his scenery well, and can draw it vigorously; he understands his frontiersmen, and can make them credible ... Upon the whole, this writer is to be welcomed; for it is much better to fail in doing a difficult thing than to succeed in doing a trifle. There is bone, fibre and sinew in Mr London. If his good angels screen him from popular success, during the next few formative years of his career, he may do something well worth the doing, and do it well. But if he is satisfied with his present level of performance, there is little hope for him." (31)

Hawthorne was the first critic to notice London's obsession with "Anglo-Saxon superiority". He commented that "The sea-flung Northmen, great muscled, deep-chested, sprung from the elements, men of sword and sweep... the dominant races come down out of the North ... a great race, half the earth its heritage and all the sea! In three score generations it rules the world!" London told his friend, Cloudesley Johns: "I do not believe in the universal brotherhood of man... I believe my race is the salt of the earth... Socialism is not an ideal system devised for the happiness of all men; it is devised for the happiness of certain kindred races. It is devised so as to give more strength to these certain kindred favoured races so that they may survive and inherit the earth to the extinction of the lesser, weaker races." (32)

The People of the Abyss

In July 1902 London moved to England where he worked with the Social Democratic Federation. He was shocked by the poverty he saw and began writing a book about slum life in London. He wrote a letter to the poet, George Sterling, about the proposed book: "How often I think of you, over there on the other side of the world! I have heard of God's country, but this country is the country God has forgotten he forget. I've read of misery, and seen a bit; but this beats anything I could even have imagined. Actually, I have seen things and looked the second time in order to convince myself that it really is so. This I know, the stuff I'm turning out will have to be expurgated or it will never see magazine publication... You will read some of my feeble efforts to describe it some day. I have my book over one-quarter done and am bowling along in a rush to finish it and get out of here. I think I should die if I had to live two years in the East End of London." (33)

In his notes, he wrote "if I were God one hour, I'd blot out all London and its 6,000,000 people, as Sodom and Gomorrah were blotted out, and look upon my work and call it good." Alex Kershaw, the author of Jack London: A Life (1997) has pointed out: "He (Jack London) was exhausted and emotionally drained. He had studied pamphlets, books and government reports on poverty, interviewed scores of men and women, taken hundreds of photographs, tramped miles of streets, stood in breadlines, slept in parks. What he had seen had seared his soul. London was more brutal in its unrelenting misery than the Klondike.... What made Jack such an effective but controversial reporter was his personal involvement. His greatest strength was his passionate bias in favour of capitalism's victims. He knew their suffering because he had felt it himself. His critics had not. Throughout his stay in London, memories of his youth had returned. Only by reassuring himself that he had escaped the conditions of his childhood could he control his fear that he might one day return to them." (34)

The People of the Abyss was published by Macmillan in 1903. It was a surprise success, selling over twenty thousand copies in America. It was not as well received in England. Charles Masterman, who lived in the East End, and was the author of From the Abysss (1902) wrote in The Daily News: "Jack London has written of the East End of London as he wrote of the Klondike, with the same tortured phrase, vehemence of denunciation, splashes of colour, and ferocity of epithet. He has studied it 'earnestly and dispassionately' - in two months! It is all very pleasant, very American, and very young." (35)

The reviewer in The Bookman accused Jack London of "snobbishness because of his profound consciousness of the gulf fixed between the poor denizens of the Abyss and the favoured class of which he is the proud representative ... he needs must assure the reader that in his own home he is accustomed to carefully prepared food and good clothes and daily tub - a fact that he might safely have left to be taken for granted". (36)

Despite these complaints, London was pleased with the book. He told to his friend, Leon Weilskov: "Of all my books I love most The People of the Abyss. No other book of mine took so much of my young heart and tears as that study of the economic degradation of the poor." (37) However, he made it clear to Anna Strunsky: "Henceforth, I shall dream romances for other people, and transmute them into bread and butter."

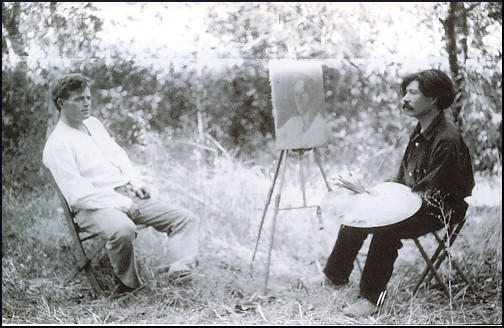

Jack London and Anna Strunsky

London returned to the United States in 1903. For a couple of years London and Anna Strunsky had been writing a joint novel, The Kempton-Wace Letters (1903). The idea came when they were onboard London's boat, The Spray. Anna later wrote: "He (Jack London) was speaking of eugenics. He was saying that love was a madness, a fever that passes, a trick. One should marry for qualities and not for love. Before marrying one should make sure one is not in love. Love is the danger signal... Jack proposed that we write a book together on eugenics and romantic love. The moon rose, paled, and faded from the sky. Then the night came awake and our sails filled. Before we landed we had our plot, a novel in letter form in which Jack was to be an American, an economist, Herbert Wace, and I am an Englishman, a poet, Dane Kempton, who stood in relation to him of father to son." (38)

James Boylan, the author of Revolutionary Lives: Anna Strunsky and William English Walling (1998) has pointed out: "They decided the method of collaboration - a real exchange of letters between her home in San Francisco and his across the bay in Oakland. Neither of them stated outright the underlying proposition, nor was there a hint of what Bessie (Jack London's wife) thought of it: that Anna would be attacking the loveless basis of his marriage, and he defending it, a possibly cataclysmic scenario." (39)

London told his friend, Cloudesley Johns: "A young Russian Jewess of San Francisco and myself have often quarrelled over our conceptions of love. She happens to be a genius. She is also a materialist by philosophy, and an idealist by innate preference, and is constantly being forced to twist all the facts of the universe in order to reconcile herself with her self. So, finally, we decided that the only way to argue the question out would be by letter." (40)

London suggested that Anna lived with him and his wife during the final revision of the book. This made Bessie London very jealous. She later claimed that Anna and her husband would rise "at the unusually early hour of half-past four in the morning and would retire to Jack's study where they remained until breakfast time... immediately after breakfast they would wander off into adjacent woods, to remain away all day." (41) Anna had a slightly different interpretation of events: "During the first few clays of my stay Mrs. London was very cordial and manifested great interest in our work, but, after a stay of five days, I became convinced that, for some reason, Mrs. London had begun to dislike me. She said nothing of any importance to make me feel out of place, but, judging from several little occurrences, I decided it was best for me to leave the London home. I carried out my resolve and left Piedinont, much against Mr. London's will." (42)

The Kempton-Wace Letters was published by Macmillan in May 1903. Despite the company spending $2,000 on advertising, the book only sold 975 copies. Jack London's friend, George Sterling, was highly critical of the book and described it as "a spiritual misprint, a typographical error half a volume long." (43) Joseph Noel, praised Strunsky's contribution: "Courage, devotion, the power to hope largely, to dream bravely, are in her pages. The simplicity of faith in life and life's processes gives dignity and beauty to nearly all she writes under the name of Dane Kempton." (44)

Call of the Wild

Jack London decided to write a novella about a dog named Buck who is a working dog during the Klondike Gold Rush. It was first published in four installments in The Saturday Evening Post, who bought it for $750. George Platt Brett of Macmillan offered to publish it as a book. He asked London to "remove the few instances of profanity in the story, because, in addition to the grown-up audience for the book, there is undoubtedly a very considerable school audience". He agreed to pay $2,000 for the story: "I like the story very well indeed, although I am afraid it is too true to nature and too good work to be really popular with the sentimentalist public." (45)

The Call of the Wild was published in July 1903. It received extremely good reviews and critics hailed it as a "classic enriching American literature", "a spellbinding animal story", "a brilliant dramatisation of the laws of nature". The literary magazine, the Criterion, described it as: "The most virile, freshly conceived, dramatically told, and firmly sustained book of the season is unquestionably Jack London's Call of the Wild... Such books as these clarify the literary atmosphere and give a new, clean vibrant breath in a depression of romances and problems; they act like an invigorating wind from the open sea upon the dullness of a sultry day." (46)

It was an immediate best-seller. The first edition of 10,000 copies sold out in 24 hours. Unfortunately for London, he had sold the rights of the book to his publisher for a flat fee of $2,000. Richard O'Connor, the author of Jack London: A Biography (1964), has argued that the novel was as good as anything Rudyard Kipling had written and had finally "struck the chord that awakened the fullest response" in American readers. (47)

Divorce

Anna Strunsky decided to spend her $500 advance for the The Kempton-Wace Letters on a trip to London. She wrote to her publisher, George Platt Brett: "The advance enables me to take a long looked-for trip to the Old World and I am very happy. While in London I shall call on Kropotkin and others. I may be able to incarnate an echo from the International Revolutionary movement into a book which will be the Uncle Tom's Cabin of the capitalist regime. Could I do this I would not so much care what became of my life, could I write the book that would serve the cause and the muse at the same time." (48)

In September, 1903, Anna received a letter from Jack London telling her that The Kempton-Wace Letters was being republished with their names together on the title page (the first edition had been published anonymously and therefore could not take advantage of London's popularity). However, the book was still not selling in large numbers: "It is a good book, a big book, and, as we anticipated, too good & too big to be popular." (49)

On her return to San Francisco Anna Strunsky discovered that London had left his wife. She wrote to London expressing sympathy: "Cameron King sent me a newspaper clipping some weeks ago. I am sorry for all the unhappiness, and I am strong in my faith. You never meant to do anything but the right and the good - poor, ever dear, dreamer! You will never do wrong. I cried over the news, half in gratitude for your strength and half in sorrow, perhaps all in sorrow, for all the sadness with which you are weighted." (50)

At the time she was unaware that rumours were circulating that she had been responsible for the break-up of the marriage. In fact, Anna had always refused to become sexually involved with London. He had written to her about his failure to seduce her in August 1902. (51) London also told his friend, Joseph Noel: "It would have to be marriage if anyone went after Anna... You know what a hell of a fuss these little intellectuals make about their virginity." (52)

Anna Strunsky was named in Bessie London's divorce petition. (53) This was leaked to the newspapers. On 30th June, 1904, the San Francisco Chronicle, interviewed Anna about the case. She complained that the scandal had reduced her mother "almost to the stage of nervous prostration." She denied the "silly little stories about lovemaking that went on before Mrs. London's eyes." Anna added that London had never behaved inappropriately: "His behavior was most circumspect toward me and always has been... He was blindly in love with his wife." (54)

Jack London had left Bessie for another woman, Charmian Kittredge, who was a friend of his wife. However, he wanted to keep this from Bessie and so he was encouraging her to believe that Anna was the woman he was involved with. London's lawyers eventually persuaded Bessie to drop her allegations in return for him agreeing to build a house for her and to make alimony and support payments. Her original claim of adultery was changed to desertion. (55)

Anna told her sister: "Jack has his divorce. There hasn't been much more unpleasantness for me though what there was was hard enough to bear. It was a plain case of blackmail. The divorce was obtained by his wife on the grounds of desertion. I am very glad he has his freedom at last. He has suffered bitterly. Further, I do not know. I hide nothing from you dearest. I think we do not love each other but I may be slandering a supreme feeling in thinking so. I am too breathless from the race for happiness and do not know. After all, I have not raced very hard. I have the Semitic temperament that gives up over readily and I have ever had a genius for giving up. I must be fought for gallantly to be won and I think lack would rather wait than fight. He, too, is tired. He is a pessimist and what has a pessimist to do with love? So, dearest, you know all." (56)

American Socialist Party

London remained active in politics and was a member of the American Socialist Party. In 1905 he joined with Upton Sinclair to form the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Other members included Norman Thomas, Clarence Darrow, Florence Kelley, Anna Strunsky, Randolph Bourne, Bertram D. Wolfe, Jay Lovestone, Rose Pastor Stokes and J.G. Phelps Stokes. Its stated purpose was to "throw light on the world-wide movement of industrial democracy known as socialism."

London followed The Call of the Wild with The Sea-Wolf (1904), The War of the Classes (1905), The Iron Heel (1907) and Martin Eden (1909), a book that sold a quarter of a million copies within a couple of months of being published in the United States. London, a heavy drinker, wrote about the problems of alcohol in his semi-autobiographical novel, John Barleycorn (1913). This was then used by the Women's Christian Temperance Union in its campaign for prohibition.

With his royalties London bought a 1,400 acre ranch. He told one interviewer that he was still a socialist but: "I've done my part, Socialism has cost me hundreds of thousands of dollars. When the time comes I'm going to stay right on my ranch and let the revolution go to blazes."

First World War

London, was disappointed by the failure of the socialist movement to prevent the First World War that began in 1914. However, unlike most members of the American Socialist Party, London did not favour the United States remaining neutral. London, who was proud of his English heritage, was a strong supporter of the Allies against the Central Powers.

In September 1914 London agreed to write a propaganda article for a book being published in protest against the German invasion of Belgium. London's anti-German feelings were revealled in his comments to his wife that: "Germany has no honour, no chivalry, no mercy. Germany is a bad sportsman. German's fight like wolves in a pack, and without initiative of resource if compelled to fight singly."

London received support from Upton Sinclair and William English Walling, but felt isolated by his opinions on the war. He was also angry about how some fellow socialists had attacked him for spending so much money on his ranch. In March, 1916, London resigned from the party claiming that the reason was its "lack of fire and fight".

Floyd Dell complained that London had lost his faith in socialism: "A few years earlier, sent to Mexico as a correspondent, he came back singing the tunes that had been taught him by the American oil-men who were engaged in looting Mexico; he preached Nordic supremacy, and the manifest destiny of the American exploiters. He had, apparently, lost faith in the revolution in which he had once believed."

In October 1916 London urged Theodore Roosevelt to run for president against Woodrow Wilson. However, he told the New York World that although he supported Roosevelt "nobody in this fat land will vote (for him) because he exalts honour and manhood over the cowardice and peace-lovingness of the worshipers of fat."

London's health deteriorated rapidly in 1916. He was suffering from uraemia, a condition that impairs the functioning of the kidneys. On 21st November, 1916, Jack London died from a morphine overdose. From the available evidence it is not clear whether this was an accident or suicide.

Floyd Dell later recalled: "His death, as a tired cynic, to whom life no longer was worth living - according to the accounts of his friends - was a miserable anti-climax. But he died too early. If he had lived a little longer, he would have seen the Russian Revolution. Life would have had some meaning for him again. He would have had something in his own vein to write about. And he might have died with honor."

Primary Sources

(1) San Francisco Chronicle (4th June, 1875)

Day before yesterday Mrs Chaney, wife of "Professor" W.H. Chaney, the astrologer, attempted suicide by taking laudanum. Failing in the effort she yesterday shot herself with a pistol in the forehead. The ball glanced off, inflicting only a flesh wound, and friends interfered before she could accomplish her suicidal purpose.

The incentive to the terrible act was domestic infelicity. Husband and wife have been known for a year past as the center of a little band of extreme Spiritualists, most of whom professed, if they did not practise, offensive free-love doctrines. To do Mr Chaney justice, he has persistently denied the holding of such broad tenets. He has been several times married before this last fiasco of the hearthstone, but it is supposed that all his former wives have been duly laid away to rest...

The last marriage took place about a year ago. Mrs Chaney, formerly Miss Flora Wellman, is a native of Ohio. She came to this coast about the time the Professor took the journey overland through the romantic sagebrush, and for a while supported herself by teaching music. It is hard to see what attracted her toward this man, to whom she was united after a short acquaintance. The union seems to have been the result of a mania like, and yet unlike, that which drew Desdemona toward the sooty Moor.

The married life of the couple is said to have been full of self-denial and devoted affection on the part of the wife, and of harsh words and unkind treatment on the part of the husband. He practised astrology, calculated horoscopes for a consideration, lectured on chemistry and astronomy, blasphemed the Christian religion, published a journal of hybrid doctrines, called the Philomathean, and pretended to calculate 'cheap nativities' on the transit of the planets for $10 each, for all of which he obtained but slender pecuniary recompense...

She says that about three weeks ago she discovered, with a natural feeling of maternal pleasure, that she was enceinte. She told her husband, and asked to be relieved for two or three months of the care of the children by means of which she had been contributing to their material support. He refused to accede to the request and some angry words followed.

Then he told her she had better destroy her unborn babe. This she indignantly declined to do, and on last Thursday morning he said to her, "Flora, I want you to pack up and leave this house." She replied, "I have no money and nowhere to go." He said, "Neither have I any to give you." A woman in the house offered her $25 but she flung it from her in a burst of anguish, saying, "What do I care for this? It will be no use to me without my husband's love."

This show of sincere affection had no effect on the flinty-headed calculator of other people's nativities. He told the poor woman that he had sold the furnishings (for which she had helped to pay) and it was useless to think of her remaining there any longer. He then left her, and shortly afterwards she made her first attempt at suicide, following it by the effort to kill herself with a pistol on the following morning, as already stated.

Failing in both endeavours, Mrs Chaney was removed in a half-insane condition from Dr Ruttley's on Mission Street to the house of a friend, where she still remains, somewhat pacified and in a mental condition indicating that she will not again attempt self-destruction. The story given here is the lady's own, as filtered through her near associates.

(2) William Chaney, letter to Jack London (28th May, 1897)

I was never married to Flora Wellman but she lived with me from June 11, 1874, until June 3, 1875. I was impotent at that time, the result of hardship, privation, and too much brain work. Therefore I cannot be your father, nor am I sure who your father is....

There was a time when I had a very tender affection for Flora; but there came a time when I hated her with all the intensity of my intense nature, and even thought of killing her myself, as many a man has under similar circumstances. Time, however, has healed the wounds and I feel no unkindness toward her, while for you I feel a warm sympathy, for I can imagine what my emotions would be were I in your place...The Chronicle published that I turned her out of doors because she would not submit to an abortion. This was copied and sent broadcast over the country. My sisters in Maine read it and two of them became my enemies. One died believing I was in the wrong. All others of my kindred, except one sister in Portland, Oregon, are still my enemies and denounce me as a disgrace to them.

I published a pamphlet at the time containing a report from a detective given me by the Chief of Police, showing that many of the slanders against me were false, but neither the Chronicle nor any of the papers that defamed me would correct the false statement. Then I gave up defending myself, and for years life was a burden. But reaction finally came, and now I have a few friends who think me respectable. I am past seventy-six, and quite poor.

(3) San Francisco Chronicle (16th February, 1896)

Jack London, who is known as the boy socialist of Oakland, is holding forth nightly to the crowds that throng City Hall Park. There are other speakers in plenty, but London always gets the biggest crowd and the most respectful attention... The young man is a pleasant speaker, more earnest than eloquent, and while he is a broad socialist in every way, he is not an anarchist. He says on the subject when asked for his definition of socialism, "It is an all-embracing term - communists, nationalists, collectionists, idealists, utopians... are all socialists, but it cannot be said that socialism is any of these - it is all." Any man, in the opinion of London, is a socialist who strives for a better form of government than the one he is living under.

(4) Jack London, letter to Anna Strunsky (21st December 1899)

Somehow I am like a fish out of water. I take to conventionality uneasily, rebelliously. I am used to saying what I think, neither more nor less. Soft equivocation is no part of me. As had I spoken to a man who came out of nowhere, shared my bed and board for a night, and passed on, so did I speak to you. Life is very short. The melancholy of materialism can never be better expressed than by Fitzgerald's "O make haste." One should have no time to dally. And further, should you know me, understand this: I, too, was a dreamer, on a farm, nay, a California ranch. But early, at only nine, the hard hand of the world was laid upon me. It was never relaxed. It has left me sentiment, but destroyed sentimentalism. It has made me practical, so that I am known as harsh, stern, uncompromising. It has taught me that reason is mightier than imagination; that the scientific man is superior to the emotional man. It has also given me a truer and a deeper romance of things, an idealism which is an inner sanctuary and which must be resolutely throttled in dealing with my kind, but which yet remains within the Holy of Holies, like an oracle, to be cherished always but to be made manifest or be consulted not on every occasion I go to market. To do this latter would bring upon me the ridicule of my fellows and make me a failure; to sum up, simply the eternal fitness of things:

All of which goes to show that people are prone to misunderstand me. May I have the privilege of not so classing you?

Nay, I did not walk down the street after Hamilton - I ran. And I had a heavy overcoat, and I was very warm and breathless. The emotional man in me had his will, and I was ridiculous.

I shall be over Saturday night. If you draw back upon yourself, what have I left ? Take me this way : a stray guest, a bird of passage, splashing with salt-rimed wings through a brief moment of your life - a rude and blundering bird, used to large airs and great spaces, unaccustomed to the amenities of confined existence. An unwelcome visitor, to be tolerated only because of the sacred law of food and blanket.

(5) Jack London, letter to Anna Strunsky (15th March, 1900)

Regarding box... please remember that I have disclosed myself in my nakedness - all those vain efforts and passionate strivings are so many weaknesses of mine which I put into your possession. Why, the grammar is often frightful, and always bad, while artistically, the whole boxful is atrocious. Now don't say I am piling it on. If I did not realize and condemn those faults I would be unable to try to do better. But - why, I think in sending that box to you I did the bravest thing I ever did in my life.

Say, do you know I am getting nervous and soft as a woman. I've got to get out again and stretch my wings or I shall become a worthless wreck. I am getting timid, do you hear? Timid! It must stop. Enclosed letter I received to-day, and it brought a contrast to me of my then 'unfailing nerve' and my present nervousness and timidity. Return it, as I suppose I shall have to answer it some day.

(6) San Francisco Evening Post (26th January, 1901)

Jack London is announced as a candidate for Mayor of Oakland... I don't know what a socialist is, but if it is anything like some of Jack London's stories, it must be something awful. I understand that as soon as Jack London is elected Mayor of Oakland by the Social Democrats the name of the place will be changed. The Social Democrats, however, have not yet decided whether they will call it London or Jacktown.

In the autumn 1901 mayoral elections, Jack received just 246 votes (the victor, John L. Davie, a wealthy populist, received 2,548). But he did succeed in his objective - to bring the principles of socialism to a wider audience through his exposure in the local press.

(7) Jack London, letter to Cloudesley Johns (45h February, 1901)

I would rather be ashes than dust! I would rather that my spark should burn out in a brilliant blaze than it should be stifled by dry rot. I would rather be a superb meteor, every atom of me in magnificent glow, than a sleepy and permanent planet. The proper function of man is to live, not to exist. I shall not waste my days in trying to prolong them. I shall use my time...

I should like to have socialism.... yet I know that socialism is not the very next step; I know that capitalism must live its life first, that the world must be exploited to the utmost first; that first must intervene a struggle for life among the nations, severer, more widespread than before. I should much prefer to wake tomorrow in a smoothly-running socialist state but I know I shall not; I know it cannot come that way. I know that the child must go through the child's sickness before it becomes a man. So, always remember that I speak of things that are; not of things that should be.

(8) Jack London, letter to Cloudesley Johns (23rd February, 1902)

Behold! I have moved! Therefore my long silence. I have been very busy. Also, I went to see a man hanged yesterday. It was one of the most scientific things I have ever seen. From the time he came through the door which leads from the death-chamber to the gallows-room, to the time he was dangling at the end of the rope, but twenty-one seconds elapsed.

And in those twenty-one seconds all the following things occurred: He walked from the door to the gallows, ascended a flight of thirteen stairs to the top of the gallows, walked across the top of the gallows to the trap, took his position upon the trap, his legs were strapped, the noose slipped over his head and drawn tight and the knot adjusted, the black cap pulled down over face, the trap sprung, his neck broken, and the spinal cord severed - all in twenty-one seconds, so simple a thing is life and so easy it is to kill a man.

Why, he made never the slightest twitch. It took fourteen and one-half minutes for the heart to run down, but he was not aware of it. One fifth of a second elapsed between the springing of the trap and the breaking of his neck and severing of his spinal cord. So far as he was concerned, he was dead at the end of that one-fifth of a second...

Lord, what a stack of hack I'm-turning out! Five mouths and ten feet, and sometimes more, so one hustles. I wonder if ever I'll get clear of debt.Am beautifully located in new house. We have a big living room, every inch of it, floor and ceiling, finished in redwood. We could put the floor space of almost four cottages (of the size of the one you can remember) into this one living room alone... We also have the cutest, snuggest little cottage right on the same ground with us, in which live my mother and my nephew... A most famous porch, broad and long and cool, a big clump of magnificent pines, flowers and flowers and flowers galore... our view commands all of San Francisco Bay for a sweep of thirty or forty miles, and all the opposing shores such as San Francisco, Marin County and Mount Tamalpais (to say nothing of the Golden Gate and the Pacific Ocean) - and all for $35.00 per month.

(9) Jack London, letter to George Sterling (22nd August, 1902)

How often I think of you, over there on the other side of the world! I have heard of God's country, but this country is the country God has forgotten he forget.

I've read of misery, and seen a bit; but this beats anything I could even have imagined. Actually, I have seen things and looked the second time in order to convince myself that it really is so. This I know, the stuff I'm turning out will have to be expurgated or it will never see magazine publication... You will read some of my feeble efforts to describe it some day.

I have my book over one-quarter done and am bowling along in a rush to finish it and get out of here. I think I should die if I had to live two years in the East End of London.

(10) In September 1905 Upton Sinclair joined with Jack London to form the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Sinclair later wrote about their first meeting.

I was prepared to give my hero the admiration of a slave. But we spent the next day together and all that day the hero smoked cigarettes and drank. He was the red-blood, and I the mollycoddle, and he must have fun with me.

(11) Floyd Dell, Homecoming (1933)

When I was in San Francisco I re-read Jack London's Martin Eden, and was struck by his description of the frightful gloom into which his hero's literary success had plunged him - a gloom which ended in suicide in the story. The account must have been fairly autobiographical. Jack London, then had been depressed by his literary success, so hard fought for; but he had explained it on rational grounds, as a bitter realization of the hollowness of achievement in bourgeoise society.

(12) The autobiographical novel about alcoholism, John Barleycorn, was used by the Women's Christian Temperance Union, to promote their campaign. Upton Sinclair later remarked on the irony of the situation.

That the work (John Barleycorn) of a drinker (Jack London) who had no intention of stopping drinking should become a major propaganda piece in the campaign for Prohibition is surely one of the ironies in the history of alcohol.

(13) Jack London, John Barleycorn (1913)

I achieved a condition in which my body was never free from alcohol. Nor did I permit myself to be away from alcohol. If I travelled to out-of-the-way places, I declined to run the risk of finding them dry. I took a quart, or several quarts, along in my grip. I was carrying a beautiful alcoholic conflagration around with me. The thing fed on its own heat and flamed the fiercer. There was no time in all my waking time, that I didn't want a drink.

(14) Jack London, letter to the Socialist Party (7th March, 1916)

I am resigning from the Socialist Party, because of its lack of fire and fight, and its loss of emphasis upon the class struggle. I was originally a member of the old revolutionary up-on-its-hind legs, a fighting, Socialist Labor Party. Trained in the class struggle, as taught and practised by the Socialist Labor Party, my own highest judgment concurring, I believed that the working class, by fighting, by fusing, by never making terms with the enemy, could emancipate itself.

Since the whole trend of Socialism in the United States during recent years has been one of peaceableness and compromise, I find that my mind refuses further sanction of my remaining a party member. Hence, my resignation.

(15) H. L. Mencken, letter to Max Broedel on the death of Jack London (24th November, 1916)

I daresay Jack London's finish was due to his chronic alcoholism in youth. He was a fearful drinker for years and ran on hard liquor. I have often argued that he was one of the few American authors who really knew how to write. The difficulty with him was that he was an ignorant and credulous man. His lack of culture caused him to embrace all sorts of socialistic bosh, and whenever he put it into his stories, he ruined them. But when he set out to tell a simple tale, he always told it superbly.

(16) Floyd Dell, Homecoming (1933)

My boyhood's Socialist hero, Jack London, had died in 1916, no hero any longer in my eyes. A few years earlier, sent to Mexico as a correspondent, he came back singing the tunes that had been taught him by the American oil-men who were engaged in looting Mexico; he preached Nordic supremacy, and the manifest destiny of the American exploiters. He had, apparently, lost faith in the revolution in which he had once believed. His death, as a tired cynic, to whom life no longer was worth living - according to the accounts of his friends - was a miserable anti-climax. But he died too early. If he had lived a little longer, he would have seen the Russian Revolution. Life would have had some meaning for him again. He would have had something in his own vein to write about. And he might have died with honor. As it was, the ending which seemed to belong rightfully to his life came to another life, that of a young man who was in many ways like Jack London - Jack Reed.

(17) International Socialist Review (April, 1917)

Our Jack is dead! He who arose from us and voiced our wrongs; who sang our hopes, and bade us stand alone, not compromise, nor pause; who bade us dare reach out and take the world in our strong hands. Comrade! Friend! Who let the sunshine in upon dark places. Great ones may not understand, nor grant you now the measure of your achievements; but, in the days to come, all men shall see.