History of San Francisco

Before the arrival of the Europeans the San Francisco area was inhabited by the Costanoans, Maidu, Miwok, Yokut and Wintu tribes. According to Tom Cole, they "were part of the Pleistocene Epoch migration of Asian peoples across the land bridge that is now the Bering Strait." This remarkably diverse group of people later known as "Indians" moved into California in successive waves beginning more than 10,000 years ago.

Kevin Starr, the author of California (2005) has argued that the Miwok and the Costanoan were the two main tribes in the San Francisco Bay area. He adds that the archaeological evidence suggests that they were "shell-fish gathering people, and over the centuries they left behind great mounds of shells from innumerable feasts". Nels Christian Nelson, did a study of the bones found in these mounds and in his book, Shellmounds of the San Francisco Bay Region (1909), and argues that these people hunted deer, elks, sea otters, beavers, badgers, squirrels, rabbits, wildcats, dogs, seals, ducks and geese.

These Native Americans obtained food from the acorns they collected each year. The Miwok mainly used the acorns of the Black Oak in the Yosemite Valley. All acorns contain tannin, which is very bitter. The Indians dealt with this problem by removing the acorn hull and to grind the interior into a flour in a stone mortar or on a flat grinding slab. They then constantly poured warm water over the flour to leach out the tannin. The leached flour was then mixed with water in a watertight basket and boiled by dropping hot stones into the gruel. Clover, grass seeds, mushrooms and pond lily roots, would be added to give it more flavour. The cooked mush was then either drunk or eaten with a spoon. Sometimes it was baked into a cake.

Alfred L. Kroeber, an anthropologist, who spent some time living with Indian tribes in California, has pointed out in Handbook of the Indians of California (1919): "The cache or granary used by the Miwok for the storage of acorns is an outdoor affair, a yard or so in diameter, a foot or two above the ground, and thatched over, beyond reach of a standing person, after it was filled... The natural branches of a tree sometimes were used in place of posts. There was no true basket construction in the cache; the sides were sticks and brush lined with grass, the whole stuck together and fied where necessary. No door was necessary: the twigs were readily pushed aside almost anywhere, and with a little start acorns rolled out in a stream. Even the squirrels had little difficulty in helping themselves at will."

The authors of the book, The Natural World of the California Indians (1980) have suggested: "Hunters had to be physically clean if deer were to allow themselves to be shot, and so the hunter bathed, stood in fragrant smoke, avoided sexual contact for a certain period before he hunted, and thought pure thoughts. Where some, today, might say that a hunter purified himself to remove the human odor, which would alarm the deer, Indians would have said that that was the way the deer wished it if they were to permit themselves to be shot... A Wintu hunter had to possess two things. First was skill in stalking deer and the ability to use his bow. Second was what was called luck, by which was meant ensuring that the spirit of the deer was not offended by the failure of the hunter to go through the proper ritual preparation."

The ethnographer, Dorothy Demetrocopoulou, has argued that the Native American's relationship with nature was "one of intimacy and mutual courtesy... he kills for a deer only when he needs it for his livelihood, and utilizes every, part of it, hoof and marrow and hide and sinew and flesh: waste is abhorrent to him, not because he believes in the intrinsic virtue of thrift, but because the deer had died for him."

Jean-François de Galaup was one of the first to record the behaviour of these tribes on the coast of California: "These Indians are extremely skillful with the bow and killed before us the smallest birds. Their patience in approaching them is inexpressible. They conceal themselves and slide in a manner after their game, seldom shooting until within fifteen paces. Their industry in hunting larger animals is still more admirable. We saw an Indian with a stag's head fastened on his own, walking on all fours and pretending to graze. He played this pantomime with such fidelity, that our hunters, when within thirty paces, would have fired at him if they had not been forewarned. In this manner they approach a herd of deer within a short distance, and kill them with their arrows."

Robert F. Heizer has argued that the Costanoans, Maidu, Miwok and Yokut, were members of the Kuksu cult: "The cult ceremonies, performed by spectacularly costumed dancers, were held in the spacious, earth-covered roundhouses which represent the largest and most complex architectural achievement of California Indians. The basic purpose of the Kuksu cult appears to have been to renew the world each year and guarantee the continuance of the natural foods (animals and plants) that supported men."

In 1542 Antonio de Mendoza, the new viceroy of New Spain, commissioned the experienced navigator, Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, to lead an expedition up the California coast in search of trade opportunities and to find the Strait of Anián, purportedly linking the Pacific and the Atlantic. On 27th June, Cabrillo sailed from the port of La Navidad along the Mexican coast north of Acapulco, rounded the tip of the Baja Peninsula and then moved slowly north. On 28th September, Cabrillo anchored in San Diego Bay. Cabrillo and his men therefore became the first Europeans to reach California from the sea.

On 8th October they visited San Pedro Bay. The following day they anchored overnight in Santa Monica Bay. Going up the coast Cabrillo saw Anacapa Island, 14 miles (23 km) off the coast, and spent the next few days in Cuyler Harbor on the island of San Miguel. On 13th November Cabrillo reached Point Reyes, but missed San Francisco bay. Coming back down the coast, Cabrillo entered Monterey Bay on 16th November.

At the end of the year Cabrillo returned to San Miguel. However, on 24th December, Cabrillo fell and broke his arm near the shoulder (some sources say it was his leg). The wound grew gangrenous and just before his death on 3rd January, 1543, he requested his chief pilot, Bartolomé Ferrelo, to continue the expedition northward. On 1st March he reached latitude 42 degrees north, later the boundary between California and Oregon, before turning south and returning to La Navidad.

In 1577, a group of investors that included Queen Elizabeth I, Sir Francis Walsingham, Christopher Hatton, John Wynter and John Hawkins, decided to support a plan for Francis Drake to take a fleet into the Pacific and raid Spanish settlements there. Two years later, Drake's The Golden Hinde was leaking badly and needed to be careened. On 17th June 1579 Drake landed in a bay on the the coast of California. According to Drake's biographer, Harry Kelsey: "Sixteenth-century accounts and maps can be interpreted to show that he stopped anywhere between the southern tip of Baja California and latitude 48° N."

Most historians believe that Drake had stopped in a bay on the Point Reyes peninsula (now known as Drake's Bay). Drake has been reported as saying: "By God's Will we hath been sent into this fair and good bay. Let us all, with one consent, both high and low, magnify and praise our most gracious and merciful God for his infinite and unspeakable goodness toward us. By God's faith hath we endured such great storms and such hardships as we have seen in these uncharted seas. To be delivered here of His safekeeping, I protest we are not worthy of such mercy."

A local group of Miwok brought him a present of a bunch of feathers and tobacco leaves in a basket. John Sugden, the author of Sir Francis Drake (1990) has argued: "It appeared to the English that the Indians regarded them as gods; they were impervious to English attempts to explain who they were, but at least they remained friendly, and when they had received clothing and other gifts the natives returned happily and noisily to their village."

On 26th June a large group of Miwok arrived at Drake's camp. The chief, wearing a head-dress and a skin cape, was followed by painted warriors, each one of whom bore a gift. At the rear of the cavalcade were women and children. A man holding a sceptre of black wood and wearing a chain of clam shells, stepped forward and made a thirty minute speech. While this was going on the women indulged in a strange ritual of self-mutilation that included scratching their faces until the blood flowed. Robert F. Heizer has argued in Elizabethan California (1974) that self-mutilation is associated with mourning and that the Miwok probably thought the British sailors were spirits returning from the dead. However, Drake took the view that they were proclaiming him king of the Miwok tribe.

Francis Drake now claimed the land for Queen Elizabeth. He named it Nova Albion "in respect of the white banks and cliffs, which lie towards the sea". Apparently, the cliffs of Point Reyes reminded Drake of the coast at Dover. Drake had a post set up with a plate bearing his name and the date of arriving in California.

When the The Golden Hinde left on 23rd July, the Miwok exhibited great distress and ran to the hill-tops to keep the ship in sight for as long as possible. Drake later wrote that during his time in California, "not withstanding it was the height of summer, we were continually visited with nipping cold, neither could we at any time within a fourteen day period find the air so clear as to be able to take height the sun or stars."

Francis Drake then sailed along the California coast but like Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo before him, failed to see the Golden Gate and San Francisco bay beyond. This is probably because the area is often shrouded in fog during the summer. The heat in the California Central Valley causes the air there to rise. This can create strong winds which pull cool moist air in from over the ocean through the break in the hills, causing a stream of dense fog to enter the bay.

The voyage across the Pacific Ocean could take as long as two hundred days and during that period most crews suffered a deadly toll of scurvy, dysentery and shipboard accidents. In the 1580s, Pedro Moya de Contreras, the viceroy of New Spain, commissioned the Portuguese adventurer, Sebastião Rodrigues Soromenho, to travel across the Pacific from the Philippines, to explore the coast of Alta California for possible ports. On 6th November, 1595, the San Agustín anchored in the same bay where the Golden Hinde had arrived in June 1579. He named the harbour the Bay of San Francisco. Soromenho continued to explore the coast but was shipwrecked close to Point Reyes on 30th November.

Another attempt was made seven years later. In 1601 the Spanish Viceroy in Mexico City, the Conde de Monterrey, commissioned Sebastián Vizcaíno, a merchant-navigator, to locate safe harbours in Alta California for Spanish ships to use on their return voyage to Acapulco from Manila. He started his journey with three ships on 5th May, 1602. His flagship was the San Diego and on 10th November, he entered and named San Diego Bay. Vizcaíno explored his way up the coast naming most of the prominent features such as Point Lobos, Carmel Valley, Monterey Bay, Sierra Point and Coyote Point. Like Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo and Francis Drake, Vizcaíno missed the entrance to San Francisco Bay.

Bad weather and scurvy forced him to return to Acapulco. Vizcaíno claimed that Monterey Bay would make the perfect harbour for galleons arriving from the Philippines. However, New Spain did not have the financial resources to establish a settlement so far to the north and nothing was done about Alta California for the next 167 years.

In 1765 King Carlos III of Spain sent José de Gálvez to New Spain with orders to organize the settlement of Alta California. Inspector General Gálvez recruited Gaspar de Portolà and Junipero Serra in what became known as the "Sacred Expedition". It was decided that three ships, the San Carlos, the San Antonio, and the San José, should sail to San Diego Bay. It was also agreed to send two parties to make an overland journey from the Baja to Alta California.

The first ship, the San Carlos, sailed from La Paz on 10th January, 1769. The other two ships left on 15th February. The first overland party, led by Fernando Rivera y Moncada, left from the Misión San Fernando Rey de España de Velicatá on 24th March. With him was Father Juan Crespi, who had been given the task of recording details of the trip. The expedition led by Portolà, which included Father Serra, set off on 15th May.

Moncada reached San Diego in May. He built a camp and waited for the others to arrive. The San Antonio, reached its destination in fifty-four days. The San Carlos took twice that time and the San José was lost with all aboard. The second overland party arrived on 1st July. Out of a total of two hundred and nineteen men who left Baja California, just over a hundred survived the journey. Some of these were to die while the San Antonio sailed back to La Paz for supplies and reinforcements.

Gaspar de Portolà and his expedition, consisting of Father Juan Crespi, and sixty-three soldiers and a hundred mules loaded down with provisions, headed north on 14th July, 1769. They reached the site of present day Los Angeles on 2nd August. The following day, they marched to what is now known as Santa Monica. Later that month they arrived at what became Santa Barbara, Portolà's party walked across the Santa Lucia Mountains to reach the mouth of the Salinas River. The fog obscured the shore and they therefore missed reaching Monterey Bay. The men had walked over a thousand miles from Misión San Fernando Rey de España de Velicatá.

In 1772, a party of sailors and missionaries, including Pedro Fages and Juan Crespi set out to explore the coast of California. Crespi later described that when they arrived at San Pablo Bay they were approached by Native Americans (probably Costanoans): "When we arrived at this place there came to us eight Indians bringing as gifts wild seeds, as the others had done; in front, an Indian dancing, with a great bunch of feathers on his head, a pipe in his mouth, in one hand a banner of feathers, and a net. These things they presented to the captain. We gave them glass beads. They stayed with us quite a while and went back well content. They are very peaceable and agreeable, and it pleased us greatly that with their beards and light colouring they looked like Spaniards."

After making a full investigation of the area Crespi reported back that without finding a good overland route to San Francisco it would be difficult to establish a mission in the area: "From all that has been seen and learned, it follows that if the new mission should be established at the harbour itself or in its near vicinity, its animals and supplies could not come to it or be brought to it by land; nor, once it were founded, could there be any communication between it and this mission of Monterey or any others that may be founded in this direction, unless a pair of good longboats are supplied, with sailors, for getting persons from one side to the other."

Viceroy Antonio María de Bucareli commissioned Juan de Ayala to explore the San Francisco area by sea. He took with him Vicente de Santa Maria, who was to be his diarist. The San Carlos left Monterey on 26th July, 1775. Rand Richards, the author of Historic San Francisco (1991) has pointed out that Ayala had a serious accident on the journey: "He was nursing what must have been a very painful wound, having accidently been shot in the foot several weeks into the voyage when a loaded pistol discharged as it was being packed away."

The San Carlos reached San Francisco Bay on 5th August. He therefore became the first European to sail through the Golden Gate. He anchored his vessel near present-day Fort Point. Ayala later reported: "From the shore's edge, some Indians begged us with the heartiest of shouts and gesticulations to come ashore. Accordingly I sent over to them in the longboat the reverend father chaplain (Vicente de Santa Maria), the first sailing master, and some men under arms, with positive orders not to offend the Indians but to please them, taking them a generous amount of earrings and glass beads. I charged our men to be discreetly on their guard, keeping the longboat ready to pull out if any quarrelling started, and I told the sailing master to leave four men in it under arms."

Vicente de Santa Mariarecorded in his journal: "Before the longboat had gone a quarter of a league it came across a rancheria of heathen who, seeing that our people were close by, left their huts and stood scattered at the shore's edge. They were not dumfounded (though naturally apprehensive at sight of people strange to them); rather, one of them, raising his voice, began with much gesticulation to make a long speech in his language, so outlandish that none of it could be understood. At the same time, they were making signs for the longboat to come near, giving assurance of peace by throwing their arrows to the ground and coming in front of them to show their innocence of treacherous dissimulation. But if danger showed not its face to the officer, he saw at least the shadow of risk to his men and did not wish to approach any nearer than was necessary for the discharge of his duty. The Indians, guessing that our men were somewhat suspicious, tried at once to make their intentions clear. They took a rod decorated with feathers and with it made signs to our men that they wished to make them a present of it; but since this met with no success they decided on a better plan, which was to draw back, all of them, and leave the gift stuck in the sand of the shore near its margin. The longboat turned back for the ship, leaving the gift untaken and reporting that the place was not as it had been thought."

The longboat returned and this time it was the Native Americans (probably Costanoans) who ran away: "The armed Indians, on seeing our men close by, hid themselves (perhaps in fear) among what oak trees they could find that would give them cover... Having reached the shore, he came upon a collection of things which, though to our notion crude, was of high value to those unfortunates, for otherwise they would not have chosen it as the best offering of their friendly generosity. This was a basketful of pinole (who knows of what seed?), some bunches of strings of woven hair, some of flat strips of tule, rather like aprons, and a sort of hairnet for the head, made of their hair, in design and shape best described as like a horse's girth, though neater and decorated at intervals with very small white snailshells. All this was near a stake driven into the sand. Limited though it was, we did not hold this unexpected friendly gift of little value; nor would it have been seemly in us to be contemptuous of a present that showed the good will of those who humbly offered it."

The following day the longboat returned with their own gifts. Vicente de Santa Maria recorded in his journal: "Our captain, touched by this indication of regard, showed on receiving it with respect a just acknowledgement of its worth. Therefore it was decided that very early the next morning the longboat should return the basket in which the Indians had given us their pinole, and in it trinkets made with bits of glass, earrings, and glass beads, our captain having first directed the officer in charge of the longboat to replace the stake and return the basket to the same place as before, very quietly, and at once return to the ship. This was done as ordered, and although there were some heathen near by, our men pretended not to have taken notice of their presence. These Indians acted almost wonderstruck at so prompt and special a return of favours, marvelling at the sight of the things sent from the ship."

Ayala spent most of the time in the bay anchored off Angel Island. He kept a detailed log of the party's activities and named two of its landmarks: Sausalito ("little thicket of willows") and Alcatraz ("island of pelicans"). Ayala was awaiting the arrival of Juan Bautista de Anza, but after 44 days in the bay he decided to return to Monterey.

Juan de Ayala reported back that he was impressed by San Francisco harbour: "This is certainly a fine harbour: it presents on sight a beautiful fitness, and it has no lack of good drinking water and plenty of firewood and ballast. Its climate, though cold, is altogether healthful and it is free from such troublesome daily fogs as there are at Monterey, since these scarcely come to its mouth and inside there are very clear days. To these many good things is added the best of all: the heathen all round this harbour are always so friendly and so docile that I had Indians aboard several times with great pleasure, and the crew as often visited them on land. In fact, from the first day to the last they were so constant in their behaviour that it behove me to make them presents of earrings, glass beads, and pilot bread, which last they learned to ask for in our language clearly."

Viceroy Antonio María de Bucareli selected Juan Bautista de Anza to lead the overland party to San Francisco Bay. He was authorized to colonize the San Francisco Bay area. He recruited colonists from among the poor in Culiacan. The expedition left Tubac on 23rd October, 1775, with 245 people (155 of them women and children), 340 horses, 165 pack mules and 302 cattle for breeding stock. Pedro Font, a Franciscan priest was selected to accompany this expedition, because of his expertise with navigation.

Anza's expedition headed north down the Santa Cruz River, arriving in Tucson on 26th October. They then followed the Gila River west, to arrive at the Colorado River and a reunion with Chief Salvador Palma, and members of the Quechan tribe on 28th November. After crossing the Colorado, the expedition broke into 3 groups so that everyone could drink from the slow-filling desert water holes. After crossing the Sonoran Desert they reached Yuha Wells on 11th December.

After experiencing a freak desert snowstorm that resulted in the death of some of their livestock, they headed up Coyote Canyon, going through San Carlos Pass on 26th December. They reached Mission San Gabriel on 4th January. Since leaving Culiacan they had been travelling for over eight months. Anza had succeeded in taking his expedition through 1,800 miles of desert wilderness.

On 17th February 1776, Anza and his expedition began their march north, reaching Monterey on 10th March. Anza arrived in California with two more people than he had left with. Three children were born along the way; one woman died in childbirth. While the colonists remained in Monterey, José Joaquín Moraga and Pedro Font, and a small group of soldiers, went ahead. On 28th March, they reached the tip of the peninsula (now named Fort Point) where Anza planted a cross signifying the place where he thought the presido should be built. Father Font, wrote in his journal that night: "I think that if it could be well settled like Europe there would not be anything more beautiful in all the world."

Rand Richards, the author of Historic San Francisco (1991) has pointed out: "While the site for the presido was perfect for its strategic value, the windswept, rocky ledge was less than ideal for a mission settlement. So the next day, after exploring further, the small band came upon a sheltered valley three miles inland to the southeast. Here the soil and climate were better and there was abundant fresh water provided by a stream-fed lagoon."

Juan Bautista de Anza returned to New Spain and left behind José Joaquín Moraga to establish the Spanish settlement in the area. On 17th June, the colonists left Monterey to join Mortaga in San Francisco. The Mission San Francisco de Asís, a log and thatch church was completed on 29th June, 1776. The mission was composed of adobe and redwood and was 144 feet long and 22 feet wide. Francisco Palóu, a former student of Father Junipero Serra, was placed in charge of the mission that had been dedicated to San Francisco de Asis. It was about 3 miles from the Golden Gate. The surrounding houses, a pueblo, became known as Yerba Buena. It was named after a sweet-smelling minty herb that grew wild in the area.

The Spanish also built a Presido at San Francisco. According to Tracy Salcedo-Chouree, the author of California's Missions and Presidios (2005): "The Presidio of San Francisco started out much as other Spanish settlements - a cluster of brush and tule huts surrounded by a palisade that housed, according to one historian, about forty soldiers and nearly 150 settlers. Adobe would replace wood and mud within a few years, with a chapel, a guardhouse, officers' residences, barracks, warehouses, and other buildings forming a square protected by a defensive wall."

Junipero Serra visited Mission San Francisco de Asís at San Francisco for the first time in September 1777. It gave him the opportunity to meet up with his friend, Francisco Palóu, who was running the mission. Afterwards he wrote: "Thanks be to God. Now Our Father Saint Francis, the crossbearer in the procession of missions, has come to the final point of the mainland of California; for in order to go farther, ships will be necessary."

The Spanish missionaries had some success at converting local Native Americans to Christianity and by 1794 the mission's population had reached 1,000. These people became known as neophytes. They were not always treated well by the missionaries. Padre José Maria Fernandez reported that large numbers left because of the "terrible suffering they experienced from punishments and work". The neophytes were very vulnerable to disease and in 1795 a measles epidemic killed large numbers. More than 200 fled the mission during the outbreak.

Father Miguel Hidalgo was a priest in Dolores, New Spain. An highly educated man, he used his knowledge to promote economic activities for the poor and rural people in his area. He established factories to make bricks and pottery and taught mestizos and local indians how to produce leather. His main objective was to make them more self-reliant and less dependent on Spanish economic policies. However, these activities violated policies designed to protect Spanish peninsular agriculture and industry, and Hidalgo was ordered to bring an end to this education system.

Hidalgo now established an alternative government in Guadalajara. On 16th September, 1810, Hidalgo declared independence from Spain. This was followed on 6th December by a decree abolishing slavery. He also abolished tribute payments that the Indians had to pay to their Spanish lords. Hidalgo also ordered the publication of a newspaper called Despertador Americano (American Wake Up Call).

Father José María Morelos, a mestizo, became leader of the military campaign. In the first nine months of the Mexican War of Independence, he won 22 victories, destroying the armies of three Spanish royalist leaders. In December, 1810, he took control of Acapulco.

Miguel Hidalgo was captured on on 21st March 1811 and taken to the city of Chihuahua. He was then found guilty of treason by a military court and executed by firing squad on 30th July. His head was cut off and displayed on the four corners of the Alhondiga de Granaditas.

Morelos now became the leader of the independence movement. The Spanish Army, under the leadership of General Félix María Calleja del Rey, besieged Morelos and his soldiers at Cuautla. On 2nd May, 1812, after 58 days, Morelos broke through the siege. Morelos arrived at Orizaba with 10,000 soldiers on 28th October 28. The city was defended by 600 Spanish soldiers. Negotiations resulted in a Spanish surrender without bloodshed.

On 13th September, 1813, the National Constituent Congress of Chilpancingo, endorsed Morelos' "Sentiments of the Nation" document that declared Mexican independence from Spain. It also abolished slavery and racial social distinctions in favor of the title "American" for all native-born individuals. Torture, monopolies and the former system of taxation were also abolished.

José María Morelos was defeated at Tezmalaca in November 1815. He was taken prisoner and brought to Mexico City in chains. He was tried and executed for treason on 22nd December, 1815 in San Cristóbal Ecatepec. After his death, his second in command, Vicente Guerrero, continued the war of independence. He remained the only major rebel leader still at large, keeping the rebellion going through an extensive campaign of guerrilla warfare.

In 1820 Viceroy Juan Ruiz de Apodaca sent an army under the leadership of General Agustín de Iturbide against the troops of Guerrero. Iturbide had a meeting with Guerrero and as a result they joined forces against Spain. On the 21st September 1821, the combined armies marched into Mexico City. Seven days later, representatives of the Spanish government and Iturbide signed the Declaration of Independence of the Mexican Empire. As a result of this document, Alta California came under the control of Mexico.

This included Yerba Buena. At the time it had a population of just over 200 people.

In 1822, William Richardson, arrived in Yerba Buena on a British whaling ship, L'Orient. There had been a dispute on board ship and he petitioned the Spanish governor for permission to remain in Alta California. He agreed as long as he promised to teach the local people at Mission San Francisco de Asís how to construct small boats for use in the bay. Richardson, who was fluent in Spanish, became the first non-Spanish European to settle in the area.

One of his first projects was the construction of a small boat which he used to move people and cargo around the bay. In 1823 Richardson converted to Catholicism, became a naturalized citizen of Mexico, and changed his name to Guillermo Antonio Richardson. Two years later he married Maria Antonia Martinez (1803–1887), the daughter of Ygnacio Martinez, commandant of the Presidio of Yerba Buena. Richardson now became involved in in the expanding California coastal trade.

Monterey was the main port of entry for Spanish ships. In 1835 Governor José Figueroa made Yerba Buena, an alternative port and invited Richardson to assume the position of Port Captain. He also started a profitable shipping company and ran the sole ferry company across the Bay. Richardson also laid out the street plan for the settlement of Yerba Buena. Later he moved his family to the 19,751 acre farm that became known as Rancho Saucelito. The local harbour became known as Richardson's Bay, and most of the ships entering Yerba Buena Cove, obtained their water and supplies there.

During this period mountain men such as Jedediah Smith, Tom Fitzpatrick, Hugh Glass, Jim Beckwourth, David Jackson, William Sublette and James Bridger began making overland trips to California. In 1833 Captain Benjamin Bonneville suggested to Joseph Walker that he should take a party of men to California. The beaver appeared to be decline in the Rocky Mountains and it was thought that new trapping opportunities would be found in this unexplored territory. Walker and his party of forty men were the first Americans to explore the Yosemite Valley.

In 1839 John Sutter moved to Yerba Buena. The following year Sutter established the colony of Nueva Helvetia (New Switzerland), which became a centre for trappers, traders and settlers in the region. The venture was a great success and within a couple of years Sutter was a wealthy businessman. Sutter had tremendous power over the area and admitted: "I was everything, patriarch, priest, father and judge." He also purchased 49,000 acres at the junction of the Feather and Sacramento rivers. This site dominated three important routes: the inland waterways from San Francisco, the trail to California across the Sierra Nevada and the Oregon-California road.

Richard Pakenham was a British diplomat serving in Mexico. In 1841 he wrote to Lord Palmerston, the foreign secretary, urging the British government "to establish an English population in the magnificent Territory of Upper California... no part of the World offering greater natural advantages for the establishment of an English colony... by all means desirable... that California, once ceasing to belong to Mexico, should not fall into the hands of any power but England... daring and adventurous speculators in the United States have already turned their thoughts in this direction."

Politicians in the United States became aware that Britain and France were both interested in taking Texas and California from Mexico. In 1842, Waddy Thompson, Jr., a former member of Congress, argued that the United States should consider taking control of California: "As to Texas I regard it as of very little value compared with California, the richest, the most beautiful and the healthiest country in the world... with the acquisition of Upper California we should have the same ascendancy on the Pacific... France and England both have had their eyes upon it." Later that year the American government asked John C. Fremont to lead an expedition to California in 1842. His reports on the fine weather, fertile land and mineral wealth in the region encouraged Americans to make the overland journey to California.

The Mission San Francisco de Asís went into decline and records show that by 1842 only 196 people were left in the settlement. This included 37 neophytes. The church was placed in the care of a secular priest and attempts were made to sell mission property.

John Sutter decided to build a frontier trading post. Completed in 1843 Sutter Fort had adobe walls eighteen feet high. Described as a "European-style fort - thick walls, gun towers, a great gate, the most ambitious fortification in California to that time". The fort had shops, houses, mills and warehouses. He also had blacksmiths, millers, bakers, carpenters, gunsmiths and blanket-makers.

In July, 1845, the United States Army, under the leadership of Zachary Taylor, arrived in Texas. Talks began with the Mexican government but on 29th December, 1845, James Polk, the president of the United States, announced Texas had become the 28th state. Some member of Congress, including Abraham Lincoln, argued against the action, believing it to be imperialist war of aggression and an attempt to seek new slave states.

General Zachary Taylor defeated the Mexicans at Palo Alto on 8th May, 1846 while General Winfield Scott organised a campaign that involved a seaborne invasion of Mexico that captured Vera Cruz and a march inland to Mexico City, which was captured on 14th September, 1846. Meanwhile General Stephen Kearny conquered New Mexico and with the support of John Fremont took control of California. General Robert Stockton appointed Fremont as governor of California.

In 1847 John Sutter and James Marshall went into partnership in the building of a sawmill at Coloma, on the South Fork of the American River, upstream from Sutter's Fort, about 115 miles northeast of San Francisco. Another man who worked for Sutter, John Bidwell, commented that "rafting sawed lumber down the cañons of the American river was a such a wild scheme... that no other man than Sutter would have been confiding and credulous to believe it practical."

On 24th January, 1848, James Marshall noticed some sparkling pebbles in the gravel bed of the tailrace his men had dug alongside the river to move the water as quickly as possible beneath the mill. He later recalled: "While we were in the habit at night of turning the water through the tail race we had dug for the purpose of widening and deepening the race, I used to go down in the morning to see what had been done by the water through the night...I picked up one or two pieces and examined them attentively; and having some general knowledge of minerals, I could not call to mind more than two which in any way resembled this, very bright and brittle; and gold, bright, yet malleable. I then tried it between two rocks, and found that it could be beaten into a different shape, but not broken."

That night John Sutter recorded in his diary: "Marshall arrived in the evening, it was raining very heavy, but he told me he came on important business. After we was alone in a private room he showed me the first specimens of gold, that is he was not certain if it was gold or not, but he thought it might be; immediately I made the proof and found that it was gold. I told him even that most of all is 23 carat gold. He wished that I should come up with him immediately, but I told him that I have to give first my orders to the people in all my factories and shops."

The gold was then showed to William Sherman: "I touched it and examined one or two of the larger pieces... In 1844, I was in Upper Georgia, and there saw some native gold, but it was much finer than this, and it was in phials, or in transparent quills; but I said that, if this were gold, it could be easily tested, first, by its malleability, and next by acids. I took a piece in my teeth, and the metallic lustre was perfect. I then called to the clerk, Baden, to bring an axe and hatchet from the backyard. When these were brought I took the largest piece and beat it out flat, and beyond doubt it was metal, and a pure metal. Still, we attached little importance to the fact, for gold was known to exist at San Fernando, at the south, and yet was not considered of much value."

James Marshall and John Sutter attempted to keep the discovery a secret. However, when Sam Brannan heard from one of Sutter's workers about the gold, he decided that he would use his newspaper to break the story. The initial reaction was for most of the adults in San Francisco to leave the town in order to become gold prospectors. Within weeks, the town's population shrank to 200 and Brannan's newspaper was forced to close.

Brannan now turned his attention to the store he had in Sutter's Fort. He purchased every available shovel, pick and pan in California. In the next seventy days he sold $36,000 in equipment (about $950,000 in today's money). Brannan's equipment was expensive because he was imposing a special tax for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. When Brigham Young heard about this he sent a messenger to collect the money. It has been claimed that Brannan replied: "You go back and tell Brigham Young that I'll give up the Lord's money when he sends me a receipt signed by the Lord."

In 1849 over 100,000 people had arrived in search of gold. During the next few years thousands more arrived. It has been argued that it was largest peacetime migration in modern history. About half came overland and the rest arrived by ship and landed in San Francisco. As Kevin Starr, the author of California (2005) has pointed out: "It could involve, at its longest, a voyage of five to eight months around Cape Horn or an overland trek of equal duration... The trip... involved high risks and probabilities of accident, fever, snakebite, alligator attack, drowning, or various forms of mayhem including robbery and murder." It has been estimated that one out of every twelve people travelling to San Francisco would die before reaching their destination. It has been claimed that the population of San Francisco doubled every ten days. By the end of 1853 the city's population was over 35,000. Of these, more than half were from foreign countries. This included large numbers of Mexicans, Germans, Chinese and Italians.

The output of gold rose from $5 million in 1848 to $40 million in 1849 and $55 million in 1851. However, only a minority of miners made much money from the Californian Gold Rush. It was much more common for people to become wealthy by providing the miners with over-priced food, supplies and services. Sam Brannan was the great beneficiary of this new found wealth. Prices increased rapidly and during this period his store had a turnover of $150,000 a month (almost $4 million in today's money).

James Marshall tried to continue with building the saw-mill: "About the middle of April the mill commenced operation, and, after cutting a few thousand feet of lumber was abandoned; as all hands were intent upon gold digging." John Sutter later recalled: "Soon as the secret was out my laborers began to leave me, in small parties first, but then all left, from the clerk to the cook, and I was in great distress... What a great misfortune was this sudden gold discovery for me! It has just broken up and ruined my hard, restless, and industrious labors, connected with many dangers of life, as I had many narrow escapes before I became properly established."

After the 1849 Gold Rush the settlers came into conflict with the Native Americans in the area. The Wintu were especially badly damaged by these events. Evelyn Wolfson has argued: "In the mid-1850s a group of white settlers in Shasta County hosted a feast for the Wintu and put poison in the food. One hundred Wintu died at the feast. The survivors tried to warn another group not to share a feast with neighbouring whites, but it was too late. Forty-five more natives died from poisoned food. Later the settlers dynamited a natural rock bridge traversing Clear Creek to keep the Wintu from crossing. They burned a Council House and killed three hundred more Indians."

Dorothy Demetrocopoulou interviewed a Wintu woman about the tribe's attitude towards the environment. "The white people never cared for land or deer or bear. When we Indians kill meat we eat it all up. When we dig roots we make little holes. When we build houses we make little holes. When we burn grass for grasshoppers we don't ruin things. We shake down acorns and pine nuts. We don't chop down the trees. We use only dead wood. But the white people plow up the ground, pull up the trees, kill everything... The spirit of the land hates them. They blast out trees and stir it up to its depths. They saw up the trees. That hurts them. The Indians never hurt anything, but the white people destroy all." It is estimated that between 1840 and 1900 the population of the Wintu fell from 14,000 to 395.

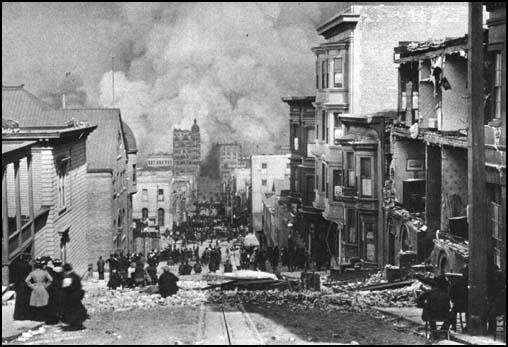

On 18th April, 1906, the San Andreas fault shifted violently and the city suffered an earthquake and was followed by a four day fire. Over 700 people died and 28,000 buildings were destroyed. Several earthquakes have taken place in the area including a serious one in 1989.

San Francisco has one of the largest ports on the West Coast and became a major source of trade with East Asia, Hawaii and Alaska. During the Second World War San Francisco was a key supply point and port of embarkation for the war in the Pacific. In 1945 the United Nations Charter was drafted at the San Francisco Conference.

San Francisco covers about 46 square miles (120 square kilometres) and in 1990 had a population of 1,585,577, the fifth largest in the United States. Finance remains one of the most important activities and is the headquarters to two of the largest commercial banks as well as the Federal Reserve Bank and the Pacific Stock Exchange.

Primary Sources

(1) Juan Crespi, account of the Pedro Fages expedition (28th March, 1772)

When we arrived at this place (San Pablo Bay) there came to us eight Indians bringing as gifts wild seeds, as the others had done; in front, an Indian dancing, with a great bunch of feathers on his head, a pipe in

his mouth, in one hand a banner of feathers, and a net. These things they presented to the captain. We gave them glass beads. They stayed with us quite a while and went back well content. They are very peaceable and agreeable, and it pleased us greatly that with their beards and light colouring they looked like Spaniards. We traveled about five leagues this day.

(2) Juan Crespi, account of the Pedro Fages expedition (30th March 1772)

From all that has been seen and learned, it follows that if the new mission should be established at the harbour itself or in its near vicinity, its animals and supplies could not come to it or be brought to it by land; nor, once it were founded, could there be any communication between it and this mission of Monterey or any others that may be founded in this direction, unless a pair of good longboats are supplied, with sailors, for getting persons from one side to the other.

May God our Lord give light to the gentlemen to whose lot it may fall to deliberate in order to reach the decision most contributive to His honour and glory and the benefit of all. Amen.

All our way from the River of St. Delfina (the Salinas River, at one day's march from the Monterey presidio) to this last place was, for me, virgin territory.

(3) Vicente de Santa Maria, journal (August, 1775)

When the longboat had returned to the ship, the captain sent it to investigate an open space, or cove, bearing west by north from us, since it appeared, on sight, to be a better place than the one where we were anchored. Before the longboat had gone a quarter of a league it came across a rancheria of heathen who, seeing that our people were close by, left their huts and stood scattered at the shore's edge. They were not dumfounded (though naturally apprehensive at sight of people strange to them); rather, one of them, raising his voice, began with much gesticulation to make a long speech in his language, so outlandish that none of it could be understood. At the same time, they were making signs for the longboat to come near, giving assurance of peace by throwing their arrows to the ground and coming in front of them to show their innocence of treacherous dissimulation. But if danger showed not its face to the officer, he saw at least the shadow of risk to his men and did not wish to approach any nearer than was necessary for the discharge of his duty. The Indians, guessing that our men were somewhat suspicious, tried at once to make their intentions clear. They took a rod decorated with feathers and with it made signs to our men that they wished to make them a present of it; but since this met with no success they decided on a better plan, which was to draw back, all of them, and leave the gift stuck in the sand of the shore near its margin. The longboat turned back for the ship, leaving the gift untaken and reporting that the place was not as it had been thought. In a little while, on a hill that bore north by west, there were seen coming nimbly down in the direction of the shore's edge three Indians. One of them, with high and rapid utterance and animated gestures, made a long harangue, directing it to our men. With a spyglass we saw them coming armed with bow and arrow, their bodies quite bare and coloured with a sort of dye that closely approached silver in hue. They were almost all the forenoon going from one place to another in hopes that the boat would come there, at times resting on their haunches and at other times moving from one part of the hill to another. In consequence, our captain ordered a Spanish flag lowered and a pennant run up, with the intention of increasing the amazement with which the Indians were doubtless already overcome. The longboat set out a third time to approach the steep rock face of that same bill, so near as to inspect its point. The armed Indians, on seeing our men close by, hid themselves (perhaps in fear) among what oak trees they could find that would give them cover. Our sailing master was looking for suitable and safe places for us to anchor but found none better than the one where Providence had placed us.

(4) Vicente de Santa Maria, journal (August, 1775)

The longboat returned to the ship, and in order to grace the occasion in person our captain went in it to see what the Indians had so generously left. Having reached the shore, he came upon a collection of things which, though to our notion crude, was of high value to those unfortunates, for otherwise they would not have chosen it as the best offering of their friendly generosity.

This was a basketful of pinole (who knows of what seed?), some bunches of strings of woven hair, some of flat strips of tule, rather like aprons,' and a sort of hairnet for the head, made of their hair, in design and shape best described as like a horse's girth, though neater and decorated at intervals with very small white snailshells. All this was near a stake driven into the sand. Limited though it was, we did not hold this unexpected friendly gift of little value; nor would it have been seemly in us to be contemptuous of a present that showed the good will of those who humbly offered it. For this reason our captain, touched by this indication of regard, showed on receiving it with respect a just acknowledgement of its worth. Therefore it was decided that very early the next morning the longboat should return the basket in which the Indians had given us their pinole, and in it trinkets made with bits of glass, earrings, and glass beads, our captain having first directed the officer in charge of the longboat to replace the stake and return the basket to the same place as before, very quietly, and at once return to the ship. This was done as ordered, and although there were some heathen near by, our men pretended not to have taken notice of their presence. These Indians acted almost wonderstruck at so prompt and special a return of favours, marvelling at the sight of the things sent from the ship. As soon as the longboat was gone they took them up and set out for their rancheria with speed, doubtless to show to others the gift which the strangers had made them. The longboat returned to the ship, and the captain and the first sailing master set out in it to make the first excursion in the reconnoitering of this new harbour. In a short time they came to a very large bay (San Francisco Bay) to which they gave the name of San Carlos.

Shortly before the longboat, returning from this venture, reached the ship, we saw on the slope of a hill that was in front of us a number of Indians coming down unhurriedly and in a quiet manner, making their way gradually to the edge of the shore. From aboard the ship we made signs to them to wait, and though they did not stop calling us over to where theywere, all of them obeyed our signs immediately and sat down.

The captain came aboard and with his permission I went in the longboat with the two sailing masters and the surgeon to communicate at close quarters with those poor unfortunates who so persistently desired us to do so, and by easy steps to bring them into close terms with us and make them the readier when the time should come for attracting them to our Holy Faith.

(5) Vicente de Santa Maria, journal (August, 1775)

Keeping watch all round to see if among the hills any treachery were afoot, we came in slowly, and when we thought ourselves safe we went ashore, the first sailing master in the lead. There came forward to greet him the oldest Indian, offering him at the end of a stick a string of beads like a rosary, made up of white shells interspersed with black knots in the thread on which they were strung. Then the rest of us who went in the longboat landed, and at once the Indian mentioned above (who came as leader among them) showed us the way to the place where they had made ready for us a number of baskets, some filled with pinole and others with loaves made with a distinctly sulphurous material that seemed to have been kneaded with some sort of oil, though its odor was so slight that we could not decide what it might be.

The sailing master accepted everything and at once returned the favour with earrings, glass beads, and other trinkets. The Indians who came on this occasion were nine in number, three being old men, two of them with sight impaired by cataracts of some sort. The six others were young men of good presence and fine stature. Their colouring was not so weak as we have seen in Indians at Carmel. They were by no means filthy, and the best favoured were models of perfection; among them was a boy whose exceeding beauty stole my heart. One alone of the young men had several dark blue lines painted from the lower lip to the waist and from the left shoulder to the right, in such a way as to form a perfect cross. God grant that we may see them worshipping so sovereign an emblem.

Besides comely elegance of figure and quite faultless countenance there was also-as their chief adornment-the way they did up their long hair: after smoothing it well they stuck in it a four-toothed wooden comb and bound up the end in a net of cord and very small feathers that were dyed a deep red; and in the middle of the coiffure was tied a sort of ribbon, sometimes black, sometimes blue. Those Indians who did not arrange their hair in this fashion did it up in a club so as to keep it in a closely woven small net that seemed to be of hemp-like fibres dyed a dark blue.

t would have seemed natural that these Indians, in their astonishment at our clothes, should have expressed a particular surprise, and no less curiosity; but they gave no sign of it. Only one of the older Indians showed himself a little unmannerly toward me; seeing that I was a thick-bearded man, he began touching the whiskers as if in surprise that I had not shaved long since. We noticed an unusual thing about the young men: none of them ventured to speak and only their elders replied to us. They were so obedient that, notwithstanding we pressed them to do so, they dared not stir a step unless one of the old men told them to; so meek that, even though curiosity prompted them, they did not raise their eyes from the ground; so docile that when my companions did me reverence by touching their lips to my sleeve and then by signs told them to do the same thing, they at once and with good grace did as they were bid.

(6) Vicente de Santa Maria, journal (August, 1775)

Accompanied by a sailor, I tried to follow them in order to pacify them with the usual gifts and to find out what it was that troubled them. With some effort we got to the top of the ridge and found there three other Indians, making six in all. Three of them were armed with bows and very sharp-tipped flint arrows. Although at first they refused to join us, nevertheless, when we had called to them and made signs of good will and friendly regard, they gradually came near. I desired them to sit down, that I might have the brief pleasure of handing out to them the glass beads and other little gifts I had had the foresight to carry in my sleeves. Throughout this interval they were in a happy frame of mind and made me hang in their ears, which they had pierced, the strings of glass beads that I had divided among them. When I had given them this pleasure, I took it into myhead to pull out my snuffbox and take a pinch; but the moment the eldest of the Indians saw me open the box he took fright and showed that he was upset. In spite of all my efforts I couldn't calm him. He fled along the trail, and so did all his companions, leaving us alone on the ridge; for which reason we went back to the shore.

(7) Vicente de Santa Maria, journal (August, 1775)

On the 15th of August the longboat set out on a reconnaissance of the northern arm of the Bay with provisions for eight days. On returning from this expedition, which went to have a look at the rivers, Jose Canizares said that in the entranceway by which the arm connects with them (Carquinez Strait) there showed themselves fifty-seven Indians of fine stature who as soon as they saw the longboat began making signs for it to come to the shore, offering with friendly gestures assurances of good will and safety. There was in authority over all these Indians one whose kingly presence marked his eminence above the rest. Our men made a landing, and when they had done so the Indian chief addressed a long speech to them.

He would not permit them to sit on the bare earth; some Indians were at once sent by the themi (which in our language means "head man") to bring some mats cleanly and carefully woven from rushes, simple ground coverings on which the Spaniards might lie at ease. Meanwhile a supper was brought them; right away came atoles, pinoles, and cooked fishes, refreshment that quieted their pangs of hunger and tickled their palates too. The pinoles were made from a seed that left me with a taste like that of toasted hazelnuts. Two kinds of atole were supplied at this meal, one lead-coloured and the other very white, which one might think to have been made from acorns. Both were well flavoured and in no way disagreeable to a palate little accustomed to atoles. The fishes were of a kind so special that besides having not one bone they were most deliciously tasty; of very considerable size, and ornamented all the way round them by six strips of little shells. The Indians did not content themselves with feasting our men, on that day when they met together, but, when the longboat left, gave more of those fishes and we had the enjoyment of them for several days.

(8) Juan Manuel de Ayala, journal (6th August, 1775)

There extended to the northeast of our ship a large cove that looked attractive and well adapted to our needs. At 9 o'clock I set out with the first sailing master to examine it, and, once there, began sounding and found fourteen to twelve fathoms depth. I intended to go to the end of it, but seeing that the tide was contrary I had to return aboard at 1 o'clock in the afternoon.

Just then, from the shore's edge, some Indians begged us with the heartiest of shouts and gesticulations to come ashore. Accordingly I sent over to them in the longboat the reverend father chaplain, the first sailing master, and some men under arms, with positive orders not to offend the Indians but to please them, taking them a generous amount of earrings and glass beads. I charged our men to be discreetly on their guard, keeping the longboat ready to pull out if any quarrelling started, and I told the sailing master to leave four men in it under arms.

From that day and our first contact with them the Indians certainly seemed friendly and wanting our men to visit their rancherias, urging them even to eat and sleep there, as they explained by signs; already they had set out at the shore a gift of pinole, bread made from their seed plants, and tamales of the same. The short time that our men were with them, it was noticed that the Indians repeated very readily all our Spanish words. I proposed to them by signs (with orders to the sailors to bring them accordingly) that they should come aboard; but by their own signs they made it clear that until our men were at their rancherias they could not come, and after our men had been with them for a while the longboat returned to the ship and the Indians disappeared.

(9) Juan Manuel de Ayala, letter to Viceroy Antonio María de Bucareli (9th November, 1775)

I have carried out the orders under which I embarked in the supply ship San Carlos and have come in from my return voyage at this harbour of San Blas this 6th day of November after having been at the harbours of Monterey and San Francisco...

After a hundred and one days of sailing I reached the harbour of Monterey, where I was obliged to stay unloading cargo and having some maintenance work done on the ship until the 27th of July. I then hoisted sail to seek out the harbour of San Francisco, which I reached on the night of the 5th of August. I stayed there forty-four days, carrying out sometimes myself, sometimes in the person of the sailing master mentioned, as faithfully as possible, the exploration of as much as could be brought under the methodical and attentive inspection the enterprise required.

This is certainly a fine harbour: it presents on sight a beautiful fitness, and it has no lack of good drinking water and plenty of firewood and ballast. Its climate, though cold, is altogether healthful and it is free from such troublesome daily fogs as there are at Monterey, since these scarcely come to its mouth and inside there are very clear days. To these many good things is added the best of all: the heathen all round this harbour are always so friendly and so docile that I had Indians aboard several times with great pleasure, and the crew as often visited them on land. In fact, from the first day to the last they were so constant in their behaviour that it behove me to make them presents of earrings, glass beads, and pilot bread, which last they learned to ask for in our language clearly.

(10) Frank Soule, Annals of San Francisco (1855)

A short experience of the mines had satisfied most of the citizens of San Francisco that, in vulgar parlance, all was not gold that glittered, and that hard work was not easy - sorry truisms for weak or lazy men.

They returned very soon to their old quarters and found that much greater profits with far less labor were to be found in supplying the necessities of the miners and speculating in real estate.

For a time, everybody made money, in spite of himself. The continued advance in the price of goods, and especially in the value of real estate, gave riches at once to the fortunate owner of a stock of the former or of a single, advantageously situated lot of the latter. When trade was brisk and profits so large, nobody grudged to pay any price or any rent for a proper place of business. Coin was scarce, but bags of gold dust furnished a circulating medium, which answered all purposes. The gamblers at the public saloons staked such bags, or were supplied with money upon them by the "banks" till the whole was exhausted.

There were few regular houses erected, for neither building materials nor sufficient labor were to be had; but canvas tents or houses of frame served the immediate needs of the place. Great quantities of goods continued to pour in from the nearer ports, till there were no longer stores to receive and cover them. In addition to Broadway Wharf, Central Wharf was projected, subscribed for, and commenced. Several other small wharves at landing places were constructed at the cost of private parties. All these, indeed, extended but a little way across the mud flat in the bay and were of no use at low tide; yet they gave considerable facilities for landing passengers and goods in open boats.

(11) Waterman L. Ormsby, The Overland Mail (1858)

It was just after sunrise that the city of San Francisco hove in sight over the hills, and never did the night traveller approach a distant light, or the lonely mariner descry a sail, with more joy than did I the city of San Francisco on the morning of Sunday, October 10. As we neared the city we met milkmen and pleasure seekers taking their morning rides, looking on with wonderment as we rattled along at a tearing pace.

Soon we struck the pavements, and, with a whip, crack, and bound, shot through the streets to our destination, to the great consternation of everything in the way and the no little surprise of everybody. Swiftly we whirled up one street and down another, and round the corners, until finally we drew up at the stage office in front of the Plaza, our driver giving a shrill blast of his horn and a nourish of triumph for the arrival of the first overland mail in San Francisco from St. Louis. But our work was not yet done. The mails must be delivered, and in a jiffy we were at the post office door, blowing the horn, howling and shouting for somebody to come and take the overland mail.

(12) General George Crook first visited San Francisco in 1852. He wrote about the city in General George Crook: His Autobiography (1889).

San Francisco was then a conglomeration of frame buildings, streets deep in sand; wharf facilities were very limited. Where the Occidental Hotel now stands there was mud and marsh which was overflowed by the tides. Everything was excitement and bustle, prices were most exhorbitant, common laborers received much higher wages than officers of the Army, although at that time, by special act of Congress, we were allowed extra pay.

Everything was so different from what I had been accustomed to that it was hard to realize I was in the United States. People had flocked there from all parts of the world; all nationalities were represented there. Sentiments and ideas were so liberal and expanded that they were almost beyond bounds. Money was so plentiful amongst citizens that it was but lightly appreciated.

The roads and walks all about the town and barracks were one mud hole. It was nothing unusual to see the tops of boots sticking out of the mud in the streets where they had been left by the wearer in preference to digging them out.

(13) Isabella Bird, A Lady's Life in the Rocky Mountains (1879)

It is a weariness to go back, even in thought, to the clang of San Francisco, which I left in its cold morning fog early yesterday, driving to the Oakland ferry through streets with sidewalks heaped with thousands of cantaloupe and water-melons, tomatoes, cucumbers, squashes, pears» grapes, peaches, apricots, - all of startling size as compared with any I ever saw before. Other streets were piled with sacks of flour, left out, all night, owing to the security from rain at this season. I pass hastily over the early part of the journey, the crossing the bay in a fog as chill as November, the number of " lunch baskets," which gave the car the look of conveying a great picnic party, the last view of the Pacific, on which I had looked for nearly a year, the fierce sunshine and brilliant sky inland, the look of long rainlessness, which one may not call drought, the valleys with sides crimson with the poison oak, the dusty vineyards, with great purple clusters thick among the leaves, and between the vines great dusty melons lying on the dusty earth. From off the boundless harvest-fields the grain was carried in June, and it is now stacked in sacks along the track, awaiting freightage. California is a " land flowing with milk and honey." The barns are bursting with fulness. In the dusty orchards the apple and pear branches are supported, that they may not break down under the weight of fruit; melons, tomatoes, and squashes of gigantic size lie almost unheeded on the ground; fat cattle, gorged almost to repletion, shade themselves under the oaks; superb "red" horses shine, not with grooming, but with condition; and thriving farms everywhere show on what a solid basis the prosperity of the "Golden State" is founded. Very uninviting, however rich, was the blazing Sacramento Valley, and very repulsive the city of Sacramento, which, at a distance of 125 miles from the Pacific, has an elevation of only thirty feet. The mercury stood at 103° in the shade, and the fine white dust was stifling.

(14) Ulysses S. Grant wrote about the Gold Rush in his Personal Memoirs (1885)

San Francisco at that day was a lively place. Gold, or placer digging as it was called, was at its height. Steamers plied daily between San Francisco and both Stockton and Sacramento. Passengers and gold from the southern mines came by the Stockton boat; from the northern mines by Sacramento. In the evening when these boats arrived, Long Wharf - there was but one wharf in San Francisco in 1852 was alive with people crowding to meet the miners as they came down to sell their “dust” and to “have a time.” Of these some were runners for hotels, boarding houses or restaurants; others belonged to a class of impecunious adventurers, of good manners and good presence, who were ever on the alert to make the acquaintance of people with some ready means, in the hope of being asked to take a meal at a restaurant. Many were young men of good family, good education and gentlemanly instincts. Their parents had been able to support them during their minority, and to give them good educations, but not to maintain them afterwards. From 1849 to 1853 there was a rush of people to the Pacific coast, of the class described, All thought that fortunes were to be picked up, without effort, in the gold fields on the Pacific. Some realized more than their most sanguine expectations; but for one such there were hundreds disappointed, many of whom now fill unknown graves; others died wrecks of their former selves, and many, without a vicious instinct, became criminals and outcasts.