Miwok

The Miwok lived along the California coast between present day Santa Rosa and Monterey, and inland to the Sierra Nevada mountains. As Stephen Powers points out in his book, Tribes of California (1876): "By much the largest nation in California, both in population and in extent of territory, is the Miwok, whose ancient dominion extended from the snow-line of the Sierra Nevada to the San Joaquin River, and from the Cosumnes to the Fresco."

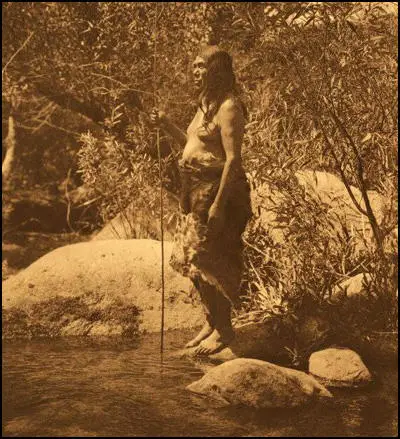

The Miwok caught salmon and sturgeon from the rivers and streams and collected clams and mussels from the sea-shore. The Miwok also hunted deer and elk in the mountains and valleys. According to the authors of The Natural World of the California Indians (1980), they "observed the dictum that one did not overhunt, and they regulated the salmon fishing by ritual in such a way as to guarantee the continuance of the supply of fish in future years." The men wore no clothing, but the women wore two-sided, deerskin aprons. When it was cold they both wore sleeve-less tunics and capes of rabbit fur.

The Miwok obtained food from the acorns they collected each year. They mainly used the acorns of the Black Oak in the Yosemite Valley. All acorns contain tannin, which is very bitter. The Indians dealt with this problem by removing the acorn hull and to grind the interior into a flour in a stone mortar or on a flat grinding slab. They then constantly poured warm water over the flour to leach out the tannin. The leached flour was then mixed with water in a watertight basket and boiled by dropping hot stones into the gruel. Clover, grass seeds, mushrooms and pond lily roots, would be added to give it more flavour. The cooked mush was then either drunk or eaten with a spoon. Sometimes it was baked into a cake.

Alfred L. Kroeber, an anthropologist, who spent some time living with Indian tribes in California, has argued in Handbook of the Indians of California (1919): "The cache or granary used by the Miwok for the storage of acorns is an outdoor affair, a yard or so in diameter, a foot or two above the ground, and thatched over, beyond reach of a standing person, after it was filled... The natural branches of a tree sometimes were used in place of posts. There was no true basket construction in the cache; the sides were sticks and brush lined with grass, the whole stuck together and fied where necessary. No door was necessary: the twigs were readily pushed aside almost anywhere, and with a little start acorns rolled out in a stream. Even the squirrels had little difficulty in helping themselves at will."

Although they did not plant crops for food the Miwok did harvest tobacco. It was smoked, mostly for soporific effects, in pipes of clay. Robert F. Heizer has argued: "Tobacco is remarkable because it was raised in a semi-horticulture: special plots were chosen, the brush was burned, seeds were planted in the ashes, and the plot was tended by thinning and weeding. Tobacco was grown in far Northern California, removed a great distance from the influences of agricultural peoples."

The Miwok passed down legends by word of mouth that explained the origin of several of the most beautiful features of the Yosemite Valley. They believed that El Capitan, was formed when two cub bears got separated from their mother. According to the story: "One hot day they slipped away from their mother and went down to the river for a swim. When they came out of the water, they were so tired that they lay down to rest on an immense, flat boulder, and fell fast asleep. While they slumbered, the huge rock began to slowly rise until at length it towered into the blue sky far above the tree-tops, and wooly, white clouds fell over the sleeping cubs like fleecy coverlets."

On 17th June 1579 Francis Drake, the captain of The Golden Hinde, landed in a bay on the the coast of California. It is now believed that Drake arrived at the Point Reyes peninsula (now known as Drake's Bay). Drake has been reported as saying: "By God's Will we hath been sent into this fair and good bay. Let us all, with one consent, both high and low, magnify and praise our most gracious and merciful God for his infinite and unspeakable goodness toward us. By God's faith hath we endured such great storms and such hardships as we have seen in these uncharted seas. To be delivered here of His safekeeping, I protest we are not worthy of such mercy."

A local group of Miwok brought him a present of a bunch of feathers and tobacco leaves in a basket. John Sugden, the author of Sir Francis Drake (1990) has argued: "It appeared to the English that the Indians regarded them as gods; they were impervious to English attempts to explain who they were, but at least they remained friendly, and when they had received clothing and other gifts the natives returned happily and noisily to their village."

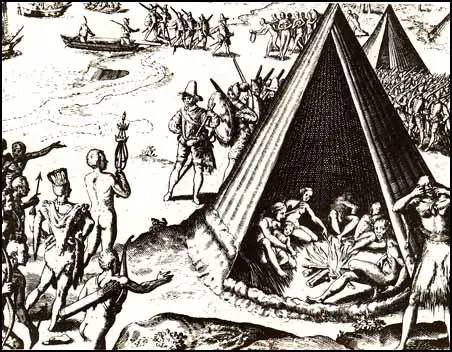

On 26th June a large group of Miwok arrived at Drake's camp. The chief, wearing a head-dress and a skin cape, was followed by painted warriors, each one of whom bore a gift. At the rear of the cavalcade were women and children. A man holding a sceptre of black wood and wearing a chain of clam shells, stepped forward and made a thirty minute speech. While this was going on the women indulged in a strange ritual of self-mutilation that included scratching their faces until the blood flowed. Robert F. Heizer has argued in Elizabethan California (1974) that self-mutilation is associated with mourning and that the Miwok probably thought the British sailors were spirits returning from the dead. However, Drake took the view that they were proclaiming him king of the Miwok tribe.

John Drake pointed out in a statement he made in 1582: "During that time (June, 1579) many Indians came there and when they saw the Englishmen they wept and scratched their faces with their nails until they drew blood, as though this was an act of homage or adoration. By signs Captain Francis Drake told them not to do that, for the Englishmen were not God. These people were peaceful and did no harm to the English, but gave them no food. They are of the colour of the Indians here (peru) and are comely. They carry bows and arrows and go naked. The climate is temperate, more cold than hot. To all appearance it is a very good country."

Father Francis Fletcher, the chaplin to the expedition, later wrote in The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake (1628): "Their men for the most part go naked, the women take a kind of bulrushes, and keeping it after the manner of hemp, make themselves thereof a loose garment, which being knitted about their middles, hangs down about their hips, and so affords to them a covering of that, which nature teaches should be hidden: about their shoulders, they also wear also the skin of a deer, with the hair upon it. They are very obedient to their husbands, and exceeding ready in all services."

Drake now claimed the land for Queen Elizabeth. He named it Nova Albion "in respect of the white banks and cliffs, which lie towards the sea". Apparently, the cliffs of Point Reyes reminded Drake of the coast at Dover. Drake had a post set up with a plate bearing his name and the date of arriving in California.

When the The Golden Hinde left on 23rd July, the Miwok exhibited great distress and ran to the hill-tops to keep the ship in sight for as long as possible. Drake later wrote that during his time in California, "not withstanding it was the height of summer, we were continually visited with nipping cold, neither could we at any time within a fourteen day period find the air so clear as to be able to take height the sun or stars."

In October, 1775, Juan Bautista de Anza left Tubac with a party of 240 soldiers and colonists, together with four civilian families, including women and children. After crossing the deserts of Arizona and California, they travelled up the coast to San Francisco Bay. They arrived on 28th March, 1776. The Mission San Francisco de Asís, a log and thatch church was completed on 29th June, 1776.

The mission was composed of adobe and redwood and was 144 feet long and 22 feet wide. Francisco Palóu, a former student of Father Junipero Serra, was placed in charge of the mission that had been dedicated to San Francisco de Asis. The Spanish missionaries had some success at converting the Ohlone to Christianity but the Miwok people fled the area.

In June, 1797, the Spanish established the Mission San José. It was the fourteenth of the 21 Spanish Missions in Alta California. According to Evelyn Wolfson the Spanish forced the Miwok to work for them. "Many Indians died from disease, overwork, and lack of nourishing food." Alfred L. Kroeber has calculated that at this time the population of the Miwok numbered 11,000 people. After a devastating measles epidemic that reduced the mission population by one quarter in 1806.

The Miwok found it difficult to avoid Americans who travelled from the east to California after the 1848 Gold Rush. As a result they died in large numbers from smallpox and other epidemics. They also suffered when the settlers diverted their streams and took away their water. The 1910 Census reported only 671 Miwok people living in the United States. By 1930 this had fallen to 491.

Primary Sources

(1) Alfred L. Kroeber, Handbook of the Indians of California (1919)

The cache or granary used by the Miwok for the storage of acorns is an outdoor affair, a yard or so in diameter, a foot or two above the ground, and thatched over, beyond reach of a standing person, after it was filled... The natural branches of a tree sometimes were used in place of posts. There was no true basket construction in the cache; the sides were sticks and brush lined with grass, the whole stuck together and fied where necessary. No door was necessary: the twigs were readily pushed aside almost anywhere, and with a little start acorns rolled out in a stream. Even the squirrels had little difficulty in helping themselves at will.

An outdoor cache coincides rather closely with the distribution of coiled basketry. None of the tribes that twine make use of any granary. This is no accident. A large storage basket is readily twined. Mere there is a feeling that the proper way to make a basket intended to be preserved is by coiling, the laboriousness of this technique would incline toward the manufacture by other processes of vessels holding several bushels.

The Miwok pound acorns with pestles in holes in granite exposures: on flat slabs laid on or sunk into the ground without basketry hopper; and grind them by crushing and rubbing on similar slabs. The conical and cylindrical mortars found in their habitat are prehistoric. Occasionally a small one is in use; but if so, it is employed by some toothless crone to crack bones, or to beat an occasional gift of a gopher or squirrel into a soft, edible pulp. Such a mortar may contain a pit or two for cracking acorns, and perhaps a groove in which bone awls have been whetted for a lifetime. In default of anything more practical the owner’s husband may now and then grind his tobacco in the same utensils. Ancient stone implements that have been put to secondary uses are rather common in California, and can still be seen in service now and then. That an object is already in use is if anything an added reason why it should be employed for another purpose. A neat people would feel differently; but a glance into almost any California Indian home suffices to reveal that these people are actuated by but little sense of order as compared with the Plains or Pueblo Indians.