Joseph Stalin

Joseph Djugashvilli (Stalin), was born in Gori, Georgia on 21st Decembe, 1879. His mother, Ekaterina Djugashvilli, was married at the age of 14 and Joseph was her fourth child to be born in less than four years. The first three died and as Joseph was prone to bad health, his mother feared on several occasions that he would also die. Understandably, given this background, Joseph's mother was very protective towards him as a child. (1)

Joseph's father, Vissarion Djugashvilli, was a bootmaker and his mother took in washing. He was an extremely violent man who savagely beat both his son and wife. As a child, Joseph experienced the poverty that most peasants had to endure in Russia at the end of the 19th century. (2)

Soso, as he was called throughout his childhood, contacted smallpox at the age of seven. It was usually a fatal disease and for a time it looked as if he would die. Against the odds he recovered but his face remained scarred for the rest of his life and other children cruelly called him "pocky". (3)

Joseph's mother was deeply religious and in 1888 she managed to obtain him a place at the local church school. Despite his health problems, he made good progress at school. However, his first language was Georgian and although he eventually learnt Russian, whenever possible, he would speak and write in his native language and never lost his distinct Georgian accent. His father died in 1890. Bertram D. Wolfe has argued "his mother, devoutly religious and with no one to devote herself to but her sole surviving child, determined to prepare him for the priesthood." (4)

Stalin left school in 1894 and his academic brilliance won him a free scholarship to the Tiflis Theological Seminary. He hated the routine of the seminary. "In the early morning when they longed to lie in, they had to rise for prayers. Then, a hurried light breakfast followed by long hours in the classroom, more prayers, a meager dinner, a brief walk around the city, and it was time for the seminary to close. By ten in the evening, when the city was just coming to life, the seminarists had said their prayers they were on their way to bed." One of his fellow students wrote: "We felt like prisoners, forced to spend our young lives in this place although innocent." (5)

Stalin told Emil Ludwig that he hated his time in the Tiflis Theological Seminary. "The basis of all their methods is spying, prying, peering into people's souls, to subject them to petty torment. What is the good in that? In protest against the humiliating regime and the jesuitical methods that prevailed in the seminary, I was ready to become, and eventually did become, a revolutionary, a believer in Marxism." (6)

While studying at the seminary he joined a secret organization called Messame Dassy (the Third Group). Members were supporters of Georgian independence from Russia. Some were also socialist revolutionaries and it was through the people he met in this organization that Stalin first came into contact with the ideas of Karl Marx. Stalin later wrote: "I became a Marxist because of my social group (my father was a worker in a shoe factory and my mother was also a working woman), but also because of the harsh intolerance and Jesuitical discipline that crushed me so mercilessly at the Seminary... The atmosphere in which I lived was saturated with hatred against Tsarist oppression." (7)

In May, 1899, Joseph Stalin left the Tiflis Theological Seminary. Several reasons were given for this action including disrespect for those in authority and reading forbidden books. According to the seminary conduct book he was expelled "as politically unreliable".Stalin was later to claim that the real reason was that he had been trying to convert his fellow students to Marxism. (8)

Stalin's mother provided a different version of events: "I wanted only one thing, that he should become a priest. He was not expelled. I brought him home on account of his health. When he entered the seminary he was fifteen and as strong as a lad could be. But overwork up to the age of nineteen pulled him down, and the doctors told me that he might develop tuberculosis. So I took him away from school. He did not want to leave. But I took him away. He was my only son." (9)

Soon after leaving the seminary he began reading Iskra (the Spark), the newspaper of the Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP). It was the first underground Marxist paper to be distributed in Russia. It was printed in several European cities and then smuggled into Russia by a network of SDLP agents. The editorial board included Alexander Potresov, George Plekhanov, Pavel Axelrod, Vera Zasulich, Lenin, Leon Trotsky and Julius Martov. (10)

Joseph Stalin and Marxism

For several months after leaving the seminary Stalin was unemployed. He eventually found work by giving private lessons to middle class children. Later, he worked as a clerk at the Tiflis Observatory. He also began writing articles for the socialist Georgian newspaper, Brdzola Khma Vladimir. Some of these were translations of articles written by Lenin. During this period he adopted the alias "Koba" (Koba was a Georgian folk hero who fought for Georgian peasants against oppressive landlords). (11)

Joseph Iremashvili, one of his Georgian comrades pointed out: "Koba became a divinity for Soso. He wanted to become another Koba, a fighter and a hero as renowned as Koba himself... His face shone with pride and joy when we called him Koba. Soso preserved that name for many years, and it became his first pseudonym when he began to write for the revolutionary newspapers." (12) He also used the name Stalin (Man of Steel) and this eventually became the name he used when he published articles in the revolutionary press. (13)

In 1901 Stalin joined the Social Democratic Labour Party and whereas most of the leaders were living in exile, he stayed in Russia where he helped to organize industrial resistance to Tsarism. On 18th April, 1902, Stalin was arrested after coordinating a strike at the large Rothschild plant at Batum and after spending 18 months in prison, Stalin was deported to Siberia. (14)

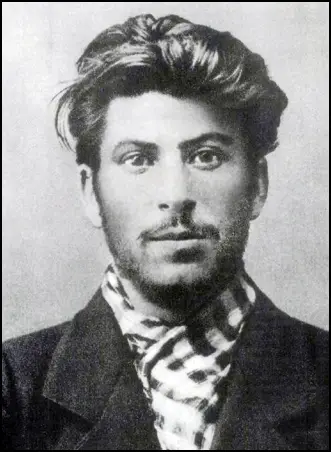

Grigol Uratadze, a fellow prisoner, later described Stalin's appearance and behaviour in prison: "He was scruffy and his pockmarked face made him not particularly neat in appearance.... He had a creeping way of walking, taking short steps.... when we were let outside for exercise and all of us in our particular groups made for this or that corner of the prison yard, Stalin stayed by himself and walked backwards and forwards with his short aces, and if anyone tried speaking to him, he would open his mouth into that cold smile of his and perhaps say a few words... we lived together in Kutaisi Prison for more than half a year and not once did I see him get agitated, lose control, get angry, shout, swear - or in short - reveal himself in any other aspect than complete calmness." (15)

At the Second Congress of the Social Democratic Labour Party held in London in 1903, there was a dispute between Lenin and Julius Martov over the future of the SDLP. Lenin argued for a small party of professional revolutionaries with a large fringe of non-party sympathizers and supporters. Martov disagreed believing it was better to have a large party of activists. Leon Trotsky commented that "the split came unexpectedly for all the members of the congress. Lenin, the most active figure in the struggle, did not foresee it, nor had he ever desired it. Both sides were greatly upset by the course of events." (16)

Although Martov won the vote 28-23 on the paragraph defining Party membership. With the support of George Plekhanov, Lenin won on almost every other important issue. His greatest victory was over the issue of the size of the Iskra editorial board to three, himself, Plekhanov and Martov. This meant the elimination of Pavel Axelrod, Alexander Potresov and Vera Zasulich - all of whom were "Martov supporters in the growing ideological war between Lenin and Martov". (17)

Trotsky argued that "Lenin's behaviour seemed unpardonable to me, both horrible and outrageous. And yet, politically it was right and necessary, from the point of view of organization. The break with the older ones, who remained in the preparatory stages, was inevitable in any case. Lenin understood this before anyone else did. He made an attempt to keep Plekhanov by separating him from Zasulich and Axelrod. But this, too, was quite futile, as subsequent events soon proved." (18)

As Lenin and Plekhanov won most of the votes, their group became known as the Bolsheviks (after bolshinstvo, the Russian word for majority), whereas Martov's group were dubbed Mensheviks (after menshinstvo, meaning minority). Stalin who was still in prison in Siberia, decided he favoured the Bolsheviks in this dispute. He escaped on 5th January 1904 and although suffering from frostbite he managed to get back to Tiflis six weeks later. (19)

Later that year he married Kato Svanidze, she was the sister of an active member of the Bolsheviks. According to a friend, Joseph Iremashvili: "His marriage was a happy one. True, it was impossible to discover in his home the equality of the sexes which he advocated... But it was not in his character to share equal rights with any other person. His marriage was a happy one because his wife, who could not measure up to him in intellect, regarded him as a demi-God." Kato died of consumption on 5th December, 1907. (20)

Bolshevism was in a small minority among the Georgian revolutionaries. Stalin wrote to Lenin: "I'm overdue with my letter, comrade. There's been neither the time nor the will to write. For the whole period it's been necessary to travel around the Caucasus, speak in debates, encourage comrades, etc. Everywhere the Mensheviks have been on the offensive and we've needed to repulse them. We've hardly had any personnel.... and so I've needed to do the work of three individuals... Our situation is as followers. Tiflis is almost completely in the hands of the Mensheviks. Half of Baku and Butumi is also with the Mensheviks." (21)

Lenin was impressed with Stalin's achievements in the Caucasus and in December 1905, he was invited to meet him in Finland. According to Robert Service, the author of Stalin: A Biography (2004): "According to his later account, he was taken aback by the unprepossessing appearance of the leader of Bolshevism. Stalin had been expecting a tall, self-regarding person. Instead he saw a man no bigger than himself and without the hauteur of the prominent émigré figures." (22)

Stalin was now a committed Bolshevik. Isaac Deutscher, the author of Stalin (1949) has argued: "Stalin was now an irreconcilable Leninist... The style of his polemics against the local bigwigs of Menshevism became more and more fanatical and bitter, reflecting both his sense of isolation among his comrades on the spot and the self-confidence imparted to him by the knowledge that he was marching in step with Lenin himself... His sense of isolation must have been the greater because of the passing of his two friends and mentors - Tsulukidze and Ketskhoveli... Ketskhoveli was shot by his jailers at the Metekhy Castle, the dreaded fortress prison of Tiflis; and Tsulukidze died of consumption." (23)

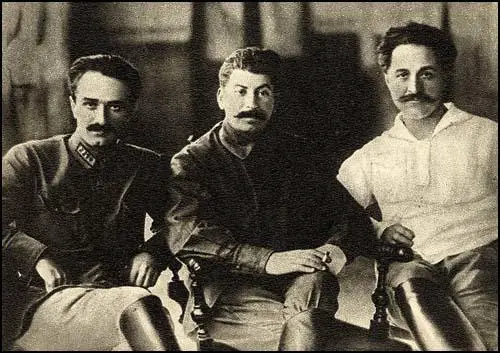

In 1907 Stalin settled in Baku where he became friends with Gregory Ordzhonikidze, Stepan Shaumyan, Kliment Voroshilov and Andrei Vyshinsky. Their leader, Lenin, went into exile with the words: "The revolutionary parties must complete their education. They had learnt how to attack... They had got to learn that victory was impossible... unless they knew both how to attack and how to retreat correctly. Of all the defeated opposition and revolution parties, the Bolsdheviks effected the most orderly retreat, with the least loss to their army." (24)

Joseph Stalin worked closely with his friends in developing the political consciousness of the workers in the region. The workers in the oil fields belonged to a union under the influence of the Bolsheviks. Stalin later wrote: "Two years of revolutionary work among the oil workers of Baku hardened me as a practical fighter and as one of the practical leaders. In contrast with advanced workers of Baku... in the storm of the deepest conflicts between workers and oil industrialists... I first learned what it meant to lead big masses of workers. There in Baku... I received my revolutionary baptism in combat." (25)

Stalin was elected as one of the delegates of the union involved in the negotiations with the employers. Gregory Ordzhonikidze commented: "While all over Russia black reaction was reigning, a genuine workers' parliament was in session at Baku." After eight months of work on the Baku committee, Ordzhonikidze and Stalin were caught by the Okhrana and put in prison. In November 1908 Ordzhonikidze and Stalin were deported to Solvychegodsk, in the northern part of the Vologda province on the Vychegda River. (26)

Bolshevik Central Committee

Joseph Stalin returned to Russia and over the next eight years he was arrested four times but each time managed to escape. He returned to St. Petersburg in February 1912, when Gregory Ordzhonikidze, Elena Stasova and Roman Malinovsky were appointed to the Russian Party Bureau, on a salary of 50 rubles per month. What they did not know was that Malinovsky was being paid 500 rubles per month by Okhrana. Stalin became editor of Pravda. Lenin, who described him as my "wonderful Georgian" arranged for him to join the Party's Central Committee. Arrested again in February 1913, Stalin was sent to the distant cold north-east of Siberia. The Bolshevik leader, Yakov Sverdlov, who was also in exile, found Stalin a difficult man to work with as he was "too much of an egoist in everyday life." (27)

After the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II, the new prime minister, Prince Georgi Lvov, allowed all political prisoners to return to their homes. Stalin arrived at Nicholas Station in St. Petersburg with Lev Kamenev on 25th March, 1917. His biographer, Robert Service, has commented: "He was pinched-looking after the long train trip and had visibly aged over the four years in exile. Having gone away a young revolutionary, he was coming back a middle-aged political veteran." The Bolshevik organizations in Petrograd were controlled by a group of young men including Vyacheslav Molotov and Alexander Shlyapnikov who had recently made arrangements for the publication of Pravda, the official Bolshevik newspaper. The young comrades were less than delighted to see these influential new arrivals. Molotov later recalled: "In 1917 Stalin and Kamenev cleverly shoved me off the Pravda editorial team. Without unnecessary fuss, quite delicately." (28)

The Petrograd Soviet recognized the authority of the Provisional Government in return for its willingness to carry out eight measures. This included the full and immediate amnesty for all political prisoners and exiles; freedom of speech, press, assembly, and strikes; the abolition of all class, group and religious restrictions; the election of a Constituent Assembly by universal secret ballot; the substitution of the police by a national militia; democratic elections of officials for municipalities and townships and the retention of the military units that had taken place in the revolution that had overthrown Nicholas II. Soldiers dominated the Soviet. The workers had only one delegate for every thousand, whereas every company of soldiers might have one or even two delegates. Voting during this period showed that only about forty out of a total of 1,500, were Bolsheviks. Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries were in the majority in the Soviet.

The Provisional Government accepted most of these demands and introduced the eight-hour day, announced a political amnesty, abolished capital punishment and the exile of political prisoners, instituted trial by jury for all offences, put an end to discrimination based on religious, class or national criteria, created an independent judiciary, separated church and state, and committed itself to full liberty of conscience, the press, worship and association. It also drew up plans for the election of a Constituent Assembly based on adult universal suffrage and announced this would take place in the autumn of 1917. It appeared to be the most progressive government in history. (29)

At this time, Stalin, like most Bolsheviks, took the view that the Russian people were not ready for a socialist revolution. He therefore called for conditional support of the Provisional Government, declaring that at this time it "would be utopian to raise the question of a socialist revolution". He also urged policies that would tempt the Mensheviks into forming an alliance. However, he disagreed with Molotov, who was calling for the immediate overthrow of Prince Georgi Lvov. The historian, Isaac Deutscher, has suggested his "middle-of-the-road attitude made him more or less acceptable to both its wings." (30)

Stalin and the April Theses

When Lenin returned to Russia on 3rd April, 1917, he announced what became known as the April Theses. Lenin attacked Bolsheviks for supporting the Provisional Government. Instead, he argued, revolutionaries should be telling the people of Russia that they should take over the control of the country. In his speech, Lenin urged the peasants to take the land from the rich landlords and the industrial workers to seize the factories. Lenin accused those Bolsheviks who were still supporting the government of Prince Georgi Lvov of betraying socialism and suggested that they should leave the party. Lenin ended his speech by telling the assembled crowd that they must "fight for the social revolution, fight to the end, till the complete victory of the proletariat". (31)

Some of the revolutionaries in the crowd rejected Lenin's ideas. Alexander Bogdanov called out that his speech was the "delusion of a lunatic." Joseph Goldenberg, a former of the Bolshevik Central Committee, denounced the views expressed by Lenin: "Everything we have just heard is a complete repudiation of the entire Social Democratic doctrine, of the whole theory of scientific Marxism. We have just heard a clear and unequivocal declaration for anarchism. Its herald, the heir of Bakunin, is Lenin. Lenin the Marxist, Lenin the leader of our fighting Social Democratic Party, is no more. A new Lenin is born, Lenin the anarchist." (32)

Joseph Stalin was in a difficult position. As one of the editors of Pravda, he was aware that he was being held partly responsible for what Lenin had described as "betraying socialism". Stalin had two main options open to him: he could oppose Lenin and challenge him for the leadership of the party, or he could change his mind about supporting the Provisional Government and remain loyal to Lenin. After ten days of silence, Stalin made his move. In the newspaper he wrote an article dismissing the idea of working with the Provisional Government. He condemned Alexander Kerensky and Victor Chernov as counter-revolutionaries, and urged the peasants to takeover the land for themselves. (33)

Stalin & the Russian Revolution

On 20th October, the Military Revolutionary Committee had its first meeting. Members included Joseph Stalin, Andrey Bubnov, Moisei Uritsky, Felix Dzerzhinsky and Yakov Sverdlov. According to Robert V. Daniels, the author of Red October: The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 (1967): "Despite Menshevik charges of an insurrectionary plot, the Bolsheviks were still vague about the role this organisation might play... Several days were to pass before the committee became an active force. Nevertheless, here was the conception, if not the actual birth, of the body which was to superintend the overthrow of the Provisional Government." (34)

Lenin continued to insist that the time was right to overthrow the Provisional Government. On 24th October he wrote a letter to the members of the Central Committee: "The situation is utterly critical. It is clearer than clear that now, already, putting off the insurrection is equivalent to its death. With all my strength I wish to convince my comrades that now everything is hanging by a hair, that on the agenda now are questions that are decided not by conferences, not by congresses (not even congresses of soviets), but exclusively by populations, by the mass, by the struggle of armed masses… No matter what may happen, this very evening, this very night, the government must be arrested, the junior officers guarding them must be disarmed, and so on… History will not forgive revolutionaries for delay, when they can win today (and probably will win today), but risk losing a great deal tomorrow, risk losing everything." (35)

Lenin insisted that the Bolsheviks should take action before the elections for the Constituent Assembly. "The international situation is such that we must make a start. The indifference of the masses may be explained by the fact that they are tired of words and resolutions. The majority is with us now. Politically things are quite ripe for the change of power. The agrarian disorders point to the same thing. It is clear that heroic measures will be necessary to stop this movement, if it can be stopped at all. The political situation therefore makes our plan timely. We must now begin thinking of the technical side of the undertaking. That is the main thing now. But most of us, like the Mensheviks and the Socialist Revolutionaries, are still inclined to regard the systematic preparation for an armed uprising as a sin. To wait for the Constituent Assembly, which will surely be against us, is nonsensical because that will only make our task more difficult." (36)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook, make a donation to Spartacus Education and subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Leon Trotsky supported Lenin's view and urged the overthrow of the Provisional Government. On the evening of 24th October, orders were given for the Bolsheviks to occupy the railway stations, the telephone exchange and the State Bank. The Smolny Institute became the headquarters of the revolution and was transformed into a fortress. Trotsky reported that the "chief of the machine-gun company came to tell me that his men were all on the side of the Bolsheviks". (37)

The Bolsheviks set up their headquarters in the Smolny Institute. The former girls' convent school also housed the Petrograd Soviet. Under pressure from the nobility and industrialists, Alexander Kerensky was persuaded to take decisive action. On 22nd October he ordered the arrest of the Bolshevik Military Revolutionary Committee. The next day he closed down the Bolshevik newspapers and cut off the telephones to the Smolny Institute.

The following day the Red Guards surrounded the Winter Palace. Inside was most of the country's Cabinet, although Kerensky had managed to escape from the city. The palace was defended by Cossacks, some junior army officers and the Woman's Battalion. At 9 p.m. The Aurora and the Peter and Paul Fortress began to open fire on the palace. Little damage was done but the action persuaded most of those defending the building to surrender. The Red Guards, led by Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, now entered the Winter Palace. (38)

On 26th October, 1917, the All-Russian Congress of Soviets met and handed over power to the Soviet Council of People's Commissars. Lenin was elected chairman and other appointments included Joseph Stalin (Nationalities), Leon Trotsky (Foreign Affairs) Alexei Rykov (Internal Affairs), Anatoli Lunacharsky (Education), Alexandra Kollontai (Social Welfare), Victor Nogin (Trade and Industry), Peter Stuchka (Justice), Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko (War), Nikolai Krylenko (War Affairs), Pavlo Dybenko (Navy Affairs), Ivan Skvortsov-Stepanov (Finance), Vladimir Milyutin (Agriculture), Ivan Teodorovich (Food), Georgy Oppokov (Justice) and Nikolai Glebov-Avilov (Posts & Telegraphs). (39)

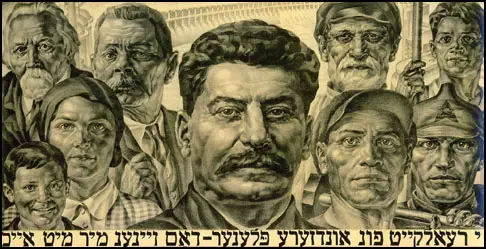

As a Georgian and a member of a minority group who had written about the problems of non-Russian peoples living under the Tsar, Stalin was seen as the obvious choice for the post as Minister of Nationalities. It was a job that gave Stalin tremendous power for nearly half the country's population fell into the category of non-Russian. Stalin now had the responsibility of dealing with 65 million Ukrainians, Georgians, Byelorussians, Tadzhiks, Buriats and Yakuts. To show his good faith, Stalin appointed several assistants from the various nationalities within Russia. (40)

The policy of the Bolsheviks was to grant the right of self-determination to all the various nationalities within Russia. This was reinforced by a speech Stalin made in Helsinki on November 16th, 1917. Stalin promised the crowd that the Soviet government would grant: "complete freedom for the Finnish people, and for other peoples of Russia, to arrange their own life!" Stalin's plan was to develop what he called "a voluntary and honest alliance" between Russia and the different national groups that lived within its borders. (41)

Over the next couple of years Stalin had difficulty controlling the non-Russian peoples under his control. Independent states were set up without his agreement. These new governments were often hostile to the Bolsheviks. Stalin had hoped that these independent states would voluntarily agree to join up with Russia to form a union of Socialist States. When this did not happen Stalin was forced to revise his policy and stated that self-determination "ought to be understood as the right of self-determination not of the bourgeoisie but of the toiling masses of a given nation." In other words, unless these independent states had a socialist government willing to develop a union with Russia, the Bolsheviks would not allow self-determination. (42)

During the Russian Civil War Lenin saw his government confronted with almost insuperable adversities. He looked round to see which of his colleagues could be relied upon to form a close nucleus capable of the determined and swift action which would be needed in the emergencies to come. He decided to set up an inner Cabinet and appointed an executive of four members: Lenin, Stalin, Leon Trotsky and Yakov Sverdlov. When Sverdlov died on 16th March, 1919, Stalin became even more important to Lenin. (43)

Lenin also changed his views on independence. He now came to the conclusion that a "modern economy required a high degree of power in the centre." Although the Bolsheviks had promised nearly half the Russian population that they would have self-determination, Lenin was now of the opinion that such a policy could pose a serious threat to the survival of the Soviet government. It was the broken promise over self-determination that was just one of the many reasons why Lenin's government became unpopular in Russia.

During the Civil War Stalin played an important administrative role in military matters and took the credit for successfully defeating the White Army at Tsaritsyn. One strategy developed by Stalin was to conduct interviews with local administrators on a large barge moored on the Volga. It was later claimed that if Stalin was not convinced of their loyalty they were shot and thrown into the river. It was claimed this is what happened to a group of supporters of Leon Trotsky. When he was questioned about this he admitted the crime: "Death solves all problems. No man, no problem." (44)

Red Terror

On 17th August, 1918, Moisei Uritsky, chief of the Petrograd Secret Police was assassinated. Two weeks later Dora Kaplan shot and severely wounded Lenin. Stalin, who was in Tsaritsyn at the time, sent a telegram to headquarters suggesting: "having learned about the wicked attempt of capitalist hirelings on the life of the greatest revolutionary, the tested leader and teacher of the proletariat, Comrade Lenin, answer this base attack from ambush with the organization of open and systematic mass terror against the bourgeoisie and its agents." (45)

The advice of Stalin was accepted and Felix Dzerzhinsky, head of the Cheka, instigated the Red Terror. The Bolsheviks newspaper, Krasnaya Gazeta, reported on 1st September, 1918: "We will turn our hearts into steel, which we will temper in the fire of suffering and the blood of fighters for freedom. We will make our hearts cruel, hard, and immovable, so that no mercy will enter them, and so that they will not quiver at the sight of a sea of enemy blood. We will let loose the floodgates of that sea. Without mercy, without sparing, we will kill our enemies in scores of hundreds. Let them be thousands; let them drown themselves in their own blood. For the blood of Lenin and Uritsky, Zinovief and Volodarski, let there be floods of the blood of the bourgeois - more blood, as much as possible." (46)

Morgan Philips Price, a journalist working for the Manchester Guardian, reported that the Red Terror was announced in Izvestia on 7th September, 1918. "There was no mistaking its meaning. It was proposed to take hostages from the former officers of the Tsar's army, from the Cadets and from the families of the Moscow and Petrograd middle-classes and to shoot ten for every Communist who fell to the White terror. Shortly after a decree was issued by the Central Soviet Executive ordering all officers of the old army within territories of the Republic to report on a certain day at certain places." (47)

Stalin married the eighteen year-old, Nadezhda Alliluyeva in 1919. Her father, Sergei Alliluyev, was a Georgian revolutionary. Stalin first met Nadezhda two years earlier. After the revolution, Nadezhda worked as a confidential code clerk in Lenin's office. In 1921 she had her Communist Party membership suspended and it was restored only on Lenin's personal intervention. (48)

Joseph Stalin : General Secretary

In 1921 Lenin became concerned with the activities of Alexandra Kollontai and Alexander Shlyapnikov, the leaders of the Workers' Opposition group. In 1921 Kollantai published a pamphlet The Workers' Opposition, where she called for members of the party to be allowed to discuss policy issues and for more political freedom for trade unionists. She also advocated that before the government attempts to "rid Soviet institutions of the bureaucracy that lurks within them, the Party must first rid itself of its own bureaucracy." (49)

The group also published a statement on future policy: "A complete change is necessary in the policies of the government. First of all, the workers and peasants need freedom. They don't want to live by the decrees of the Bolsheviks; they want to control their own destinies. Comrades, preserve revolutionary order! Determinedly and in an organized manner demand: liberation of all arrested Socialists and non-partisan working-men; abolition of martial law; freedom of speech, press and assembly for all who labour." (50)

At the Tenth Party Congress in April 1922, Lenin proposed a resolution that would ban all factions within the party. He argued that factions within the party were "harmful" and encouraged rebellions such as the Kronstadt Rising. The Party Congress agreed with Lenin and the Workers' Opposition was dissolved. Stalin was appointed as General Secretary and was now given the task of dealing with the "factions and cliques" in the Communist Party. (51)

Stalin's main opponents for the future leadership of the party failed to see the importance of this position and actually supported his nomination. They initially saw the post of General Secretary as being no more that "Lenin's mouthpiece". According to Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996): "Factionalism became punishable by expulsion. Lenin sought to stifle the very possibility of opposition. The wording of this resolution, unthinkable in a democratic party, grated on the ear, and it was therefore kept secret from the public." (52)

Roy A. Medvedev, has argued in Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism (1971) that on the surface it was a strange decision: "In 1922 Stalin was the least prominent figure in the Politburo. Not only Lenin but also Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev, Bukharin, and A. I. Rykov were much more popular among the broad masses of the Party than Stalin. Close-mouthed and reserved in everyday affairs, Stalin was also a poor public speaker. He spoke in a low voice with a strong Caucasian accent, and found it difficult to speak without a prepared text. It is not surprising that, during the stormy years of revolution and civil war, with their ceaseless meetings, rallies, and demonstrations, the revolutionary masses saw or heard little of Stalin." (53)

Isaac Deutscher, the author of Stalin (1949) has pointed out: "The leading bodies of the party were now top-heavy; and a new office, that of the General Secretary, was created, which was to coordinate the work of their many growing and overlapping branches... Soon afterwards a latent dualism of authority began to develop at the very top of the party. The seven men who now formed the Politbureau (in addition to the previous five, Zinoviev and Tomsky had recently been elected) represented, as it were, the brain and the spirit of Bolshevism. In the offices of the General Secretariat resided the more material power of management and direction." (54)

Soon after Stalin's appointment as General Secretary, Lenin went into hospital to have a bullet removed from his body that had been there since Dora Kaplan's assassination attempt. It was hoped that this operation would restore his health. This was not to be; soon afterwards, a blood vessel broke in Lenin's brain. This left him paralyzed all down his right side and for a time he was unable to speak. As "Lenin's mouthpiece", Joseph Stalin had suddenly become extremely important. (55)

While Lenin was immobilized, Stalin made full use of his powers as General Secretary. At the Party Congress he had been granted permission to expel "unsatisfactory" party members. This enabled Stalin to remove thousands of supporters of Leon Trotsky, his main rival for the leadership of the party. As General Secretary, Stalin also had the power to appoint and sack people from important positions in the government. The new holders of these posts were fully aware that they owed their promotion to Stalin. They also knew that if their behaviour did not please him they would be replaced.

Surrounded by his supporters, Stalin's confidence began to grow. In October, 1922, he disagreed with Lenin over the issue of foreign trade. When the matter was discussed at Central Committee, Stalin's rather than Lenin's policy was accepted. Lenin began to fear that Stalin was taking over the leadership of the party. Lenin wrote to Trotsky asking for his support. Trotsky agreed and at the next meeting of the Central Committee the decision on foreign trade was reversed. Lenin, who was too ill to attend, wrote to Trotsky congratulating him on his success and suggesting that in future they should work together against Stalin.

Joseph Stalin, whose wife Nadya Alliluyeva worked in Lenin's private office, soon discovered the contents of the letter sent to Leon Trotsky. Stalin was furious as he realized that if Lenin and Trotsky worked together against him, his political career would be at an end. In a fit of temper Stalin made an abusive phone-call to Lenin's wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, accusing her of endangering Lenin's life by allowing him to write letters when he was so ill. (56)

After Krupskaya told her husband of this phone-call, Lenin made the decision that Stalin was not the man to replace him as the leader of the party. Lenin knew he was close to death so he dictated to his secretary a letter that he wanted to serve as his last "will and testament". The document was comprised of his thoughts on the senior members of the party leadership. Lenin stated: "Comrade Stalin, having become General Secretary, has concentrated enormous power in his hands: and I am not sure that he always knows how to use that power with sufficient caution. I therefore propose to our comrades to consider a means of removing Stalin from this post and appointing someone else who differs from Stalin in one weighty respect: being more tolerant, more loyal, more polite, more considerate of his comrades." (57)

A few days later Lenin added a postscript to his earlier testament: "Stalin is too rude, and this fault... becomes unbearable in the office of General Secretary. Therefore, I propose to the comrades to find a way to remove Stalin from that position and appoint to it another man... more patient, more loyal, more polite and more attentive to comrades, less capricious, etc. This circumstance may seem an insignificant trifle, but I think that from the point of view of preventing a split and from the point of view of the relations between Stalin and Trotsky... it is not a trifle, or it is such a trifle as may acquire a decisive significance." Three days after writing this testament Lenin had a third stroke. Lenin was no longer able to speak or write and although he lived for another ten months, he ceased to exist as a power within the Soviet Union. (58)

Lenin died of a heart attack on 21st January, 1924. Stalin reacted to the news by announcing that Lenin was to be embalmed and put on permanent display in a mausoleum to be erected on Red Square. Lenin's wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, immediately objected because she disliked the "quasi-religious" implications of this decision. Despite these objections, Stalin carried on with the arrangements. "Lenin, who detested hero worship and fought religion as an opiate for the people, who canonized in the interest of Soviet politics and his writings were given the character of Holy Writ." (59)

The funeral took place on 27th January, and Stalin was a pallbearer with Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Nickolai Bukharin, Vyacheslav Molotov, Felix Dzerzhinsky, Alexander Schottmann and Maihail Tomsky. Stalin gave a speech which ended with the words: "Leaving us, comrade Lenin left us a legacy of fidelity to the principles of the Communist International. We swear to you, comrade Lenin, that we will not spare our own lives in strengthening and broadening the union of labouring people of the whole world - the Communist International." (60) As Robert Service has pointed out: "Christianity had to give way to communism and Lenin was to be presented to society as the new Jesus Christ." (61)

It was assumed that Leon Trotsky would replace Lenin as leader when he died. To stop this happening Stalin established a close political relationship with Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev. The three men became known as the "triumvirate". The historian, Isaac Deutscher, the author of Stalin (1949) has pointed out: "What made for the solidarity of the three men was their determination to prevent Trotsky from succeeding to the leadership of the party. Separately, neither could measure up to Trotsky. Jointly, they represented a powerful combination of talent and influence. Zinoviev was the politician, the orator, the demagogue with popular appeal. Kamenev was the strategist of the group, its solid brain, trained in matters of doctrine, which were to play a paramount part in the contest for power. Stalin was the tactician of the triumvirate and its organizing force. Between them, the three men virtually controlled the whole party and, through it, the Government." (62)

Simon Sebag Montefiore, the author of Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar (2003), pointed out that an important point of his strategy was to promote his friends, Vyacheslav Molotov, Kliment Voroshilov and Gregory Ordzhonikidze: "An outsider in 1924 would have expected Trotsky to succeed Lenin, but in the Bolshevik oligarchy, this glittery fame counted against the insouciant War Commissar. The hatred between Stalin and Trotsky was not only based on personality and style but also on policy. Stalin had already used the massive patronage of the Secretariat to promote his allies, Vyacheslav Molotov, Kliment Voroshilov and Grigory Konstantinovich; he also supplied an encouraging and realistic alternative to Trotsky's insistence on European revolution: 'Socialism in One Country'. The other members of the Politburo, led by Grigory Zinoviev, and Kamenev, Lenin's closest associates, were also terrified of Trotsky, who had united all against himself." (63)

Some of Trotsky's supporters pleaded with him to organise a military coup. As People's Commissar of Military and Naval Affairs and as leader of the Red Army during the Civil War. However, Trotsky rejected the idea and instead resigned his post. Trotsky was now vulnerable and Kamanev and Zinoviev were in favour of having him arrested and put on trial. Stalin rejected this idea and feared that at this stage, any attempt to punish him would result in the party splitting into two hostile factions. Before dealing with Trotsky, Stalin had to prepare the party for the purge that he wanted to take place. (64)

At the Communist Party Congress in May, 1923, Stalin admitted that the triumvirate existed. In reply to a speech made by a delegate he argued: "Osinsky has praised Stalin and praised Kamenev, but he has attacked Zinoviev, thinking that for the time being it would be enough to remove one of them and that then would come the turn of the others. His aim is to break up that nucleus that has formed itself inside the Central Committee over years of toil... I ought to warn him that he will run into a wall, against which, I am afraid, he will smash his head." To another critic, who demanded more freedom of discussion in the party, Stalin replied that the party was no debating society. Russia was "surrounded by the wolves of imperialism; and to discuss all important matters in 20,000 party cells would mean to lay all one's cards before the enemy." (65)

Stalin and Trotsky

In October 1923, Yuri Piatakov drafted a statement that was published under the name Platform of the 46 which criticized the economic policies of the party leadership and accused it of stifling the inner-party debate. It echoed the call made by Leon Trotsky, a week earlier, calling for a sharp change of direction by the party. The statement was also signed by Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, Andrey Bubnov, Ivan Smirnov, Lazar Kaganovich, Ivar Smilga, Victor Serge, Evgenia Bosh and thirty-eight other leading Bolsheviks.

"The extreme seriousness of the position compels us (in the interests of our Party, in the interests of the working class) to state openly that a continuation of the policy of the majority of the Politburo threatens grievous disasters for the whole Party. The economic and financial crisis beginning at the end of July of the present year, with all the political, including internal Party, consequences resulting from it, has inexorably revealed the inadequacy of the leadership of the Party, both in the economic domain, and especially in the domain of internal Party, relations."

The document then went on to complain about the lack of debate in the Communist Party: "Similarly in the domain of internal party relations we see the same incorrect leadership paralyzing and breaking up the Party; this appears particularly clearly in the period of crisis through which we are passing. We explain this not by the political incapacity of the present leaders of the Party; on the contrary, however much we differ from them in our estimate of the position and in the choice of means to alter it, we assume that the present leaders could not in any conditions fail to be appointed by the Party to the out-standing posts in the workers’ dictatorship. We explain it by the fact that beneath the external form of official unity we have in practice a one-sided recruitment of individuals, and a direction of affairs which is one-sided and adapted to the views and sympathies of a narrow circle. As the result of a Party leadership distorted by such narrow considerations, the Party is to a considerable extent ceasing to be that living independent collectivity which sensitively seizes living reality because it is bound to this reality with a thousand threads." (66)

Isaac Deutscher, the author of Stalin (1949) has argued: "Among the signatories were: Piatakov, one of the two ablest leaders of the young generation mentioned in Lenin's testament, Preobrazhensky and Serebriakov, former secretaries of the Central Committee, Antonov-Ovseenko, the military leader of the October revolution, Srnirnov, Osinsky, Bubnov, Sapronov, Muralov, Drobnis, and others, distinguished leaders in the civil war, men of brain and character. Some of them had led previous oppositions against Lenin and Trotsky, expressing the malaise that made itself felt in the party as its leadership began to sacrifice first principles to expediency. Fundamentally, they were now voicing that same malaise which was growing in proportion to the party's continued departure from some of its first principles. It is not certain whether Trotsky directly instigated their demonstration." Lenin commented that Piatakov might be "very able but not to be relied upon in a serious political matter". (67)

Two months later, Leon Trotsky published an open letter where he called for more debate in the Communist Party concerning the way the country was being governed. He argued that members should exercise its right to criticism "without fear and without favour" and the first people to be removed from party positions are "those who at the first voice of criticism, of objection, of protest, are inclined to demand one's party ticket for the purpose of repression". Trotsky went on to suggest that anyone who "dares to terrorize the party" should be expelled. (68)

Stalin objected to the idea of democracy in the Communist Party. "I shall say but this, there will plainly not be any developed democracy, any full democracy." At this time "it would be impossible and it would make no sense to adopt it" even within the narrow limits of the party. Democracy could only be introduced when the Soviet Union enjoyed "economic prosperity, military security, and a civilized membership." Stalin added that though the party was not democratic, it was wrong to claim it was bureaucratic. (69)

Gregory Zinoviev was furious with Trotsky for making these comments and proposed that he should be immediately arrested. Stalin, aware of Trotsky's immense popularity, opposed the move as being too dangerous. He encouraged Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev to attack Trotsky whereas he wanted to give the impression that he was the most moderate, sensible, and conciliatory of the triumvirs. Kamenev asked him about the question of gaining a majority in the party, Stalin replied: "Do you know what I think about this? I believe that who votes how in the party is unimportant. What is extremely important is who counts the votes and how they are recorded." (70)

In April 1924 Joseph Stalin published Foundations of Leninism. In the introduction he argued: "Leninism grew up and took shape under the conditions of imperialism, when the contradictions of capitalism had reached an extreme point, when the proletarian revolution had become an immediate practical question, when the old period of preparation of the working class for revolution had arrived at and passed into a new period, that of direct assault on capitalism... The significance of the imperialist war which broke out ten years ago lies, among other things, in the fact that it gathered all these contradictions into a single knot and threw them on to the scales, thereby accelerating and facilitating the revolutionary battles of the proletariat. In other words, imperialism was instrumental not only in making the revolution a practical inevitability, but also in creating favourable conditions for a direct assault on the citadels of capitalism. Such was the international situation which gave birth to Leninism." (71)

According to his personal secretary Boris Bazhanov, Stalin had the facility to evesdrop on the conversations of dozens of the most influential communist leaders. Before meetings of the Politburo Stalin would neet with his supporters. This included Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, Lazar Kaganovich, Vyacheslav Molotov, Gregory Ordzhonikidze, Sergy Kirov and Kliment Voroshilov. As Robert Service, the author of Stalin: A Biography (2004), has pointed out: "He demanded efficiency as well as loyalty from the gang members. He also selected them for their individual qualities. He created an ambience of conspiracy, companionship and crude masculine humour. In return for their services he looked after their interests." (72)

Leon Trotsky accused Joseph Stalin of being dictatorial and called for the introduction of more democracy into the party. Zinoviev and Kamenev united behind Stalin and accused Trotsky of creating divisions in the party. Trotsky's main hope of gaining power was for Lenin's last testament to be published. In May, 1924, Lenin's widow, Nadezhda Krupskaya, demanded that the Central Committee announce its contents to the rest of the party. Zinoviev argued strongly against its publication. He finished his speech with the words: "You have all witnessed our harmonious cooperation in the last few months, and, like myself, you will be happy to say that Lenin's fears have proved baseless." The new members of the Central Committee, who had been sponsored by Stalin, guaranteed that the vote went against Lenin's testament being made public. (73)

Trotsky and Stalin clashed over the future strategy of the country. Stalin favoured what he called "socialism in one country" whereas Trotsky still supported the idea of world revolution. He was later to argue: "The utopian hopes of the epoch of military communism came in later for a cruel, and in many respects just, criticism. The theoretical mistake of the ruling party remains inexplicable, however, only if you leave out of account the fact that all calculations at that time were based on the hope of an early victory of the revolution in the West." (74)

Trotsky had argued in 1917 that the Bolshevik Revolution was doomed to failure unless successful revolutions also took place in other countries such as Germany and France. Lenin had agreed with him about this but by 1924 Stalin began talking about the possibility of completing the "building of socialism in a single country". Nikolay Bukharin joined the attacks on Trotsky asserted that Trotsky's theory of "permanent revolution" was anti-Leninist. (75)

In January 1925, Stalin was able to arrange for Leon Trotsky to be removed from the government. Isaac Deutscher, the author of Stalin (1949) has argued: "He left office without the slightest attempt at rallying in his defence the army he had created and led for seven years. He still regarded the party, no matter how or by whom it was led, as the legitimate spokesman of the working-class. If he were to oppose army to party, so he reasoned, he would have automatically set himself up as the agent for some other class interests, hostile to the working-class... He still remained a member of the Politbureau, but for more than a year he kept aloof from all public controversy." (76)

With the decline of Trotsky, Joseph Stalin felt strong enough to stop sharing power with Lev Kamenev and Gregory Zinoviev. Stalin now began to attack Trotsky's belief in the need for world revolution. He argued that the party's main priority should be to defend the communist system that had been developed in the Soviet Union. This put Zinoviev and Kamenev in an awkward position. They had for a long time been strong supporters of Trotsky's theory that if revolution did not spread to other countries, the communist system in the Soviet Union was likely to be overthrown by hostile, capitalist nations. However, they were reluctant to speak out in favour of a man whom they had been in conflict with for so long. (77)

Stalin & the New Economic Policy

Joseph Stalin now formed an alliance with Nikolay Bukharin, Mikhail Tomsky and Alexei Rykov, on the right of the party, who wanted an expansion of the New Economic Policy that had been introduced several years earlier. Farmers were allowed to sell food on the open market and were allowed to employ people to work for them. Those farmers who expanded the size of their farms became known as kulaks. Bukharin believed the NEP offered a framework for the country's more peaceful and evolutionary "transition to socialism" and disregarded traditional party hostility to kulaks. (78)

Robert Service, the author of Stalin: A Biography (2004), argued: "Stalin and Bukharin rejected Trotsky and the Left Opposition as doctrinaires who by their actions would bring the USSR to perdition... Zinoviev and Kamenev felt uncomfortable with so drastic a turn towards the market economy... They disliked Stalin's movement to a doctrine that socialism could be built in a single country - and they simmered with resentment at the unceasing accumulation of power by Stalin." (79)

When Stalin was finally convinced that Lev Kamenev and Gregory Zinoviev were unwilling to join forces with Leon Trotsky against him, he began to support openly the economic policies of right-wing members of the Politburo. They now realized what Stalin was up to but it took them to summer of 1926 before they could swallow their pride and join with Trotsky against Stalin. Kamenev argued: "We're against creating a theory of the leader; were against making anyone into the leader... Were against the Secretariat, by actually combining politics and organisation, standing above the political body… Personally I suggest that our General Secretary is not the kind of figure who can unite the old Bolshevik high command around him. It is precisely because I've often said this personally to comrade Stalin and precisely because I've often said this to a group of Leninist comrades that I repeat it at the Congress: I have come to the conclusion that comrade Stalin is incapable of performing the role of unifier of the Bolshevik high command." (80)

Kamenev and Zinoviev denounced the pro-Kulak policy, arguing that the stronger the big farmers grew the easier it would be for them to withhold food from the urban population and to obtain more and more concessions from the government. Eventually, they might be in a position to overthrow communism and the restoration of capitalism. Before the Russian Revolution there had been 16 million farms in the country. It now had 25 million, some of which were very large and owned by kulaks. They argued that the government, in order to undermine the power of the kulaks, should create large collective farms. (81)

Stalin tried to give the impression he was an advocate of the middle-course. In reality, he was supporting those on the right. In October, 1925, the leaders of the left in the Communist Party submitted to the Central Committee a memorandum in which they asked for a free debate on all controversial issues. This was signed by Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, Grigori Sokolnikov, the Commissar of Finance, and Nadezhda Krupskaya, the widow of Lenin. Stalin rejected this idea and continued to have complete control over government policy. (82)

On the advice of Nikolay Bukharin, all restrictions upon the leasing of land, the hiring of labour and the accumulation of capital were removed. Bukharin's theory was that the small farmers only produced enough food to feed themselves. The large farmers, on the other hand, were able to provide a surplus that could be used to feed the factory workers in the towns. To motivate the kulaks to do this, they had to be given incentives, or what Bukharin called "the ability to enrich" themselves. (83) The tax system was changed in order to help kulaks buy out smaller farms. In an article in Pravda, Bukharin wrote: "Enrich yourselves, develop your holdings. And don't worry that they may be taken away from you." (84)

At the 14th Congress of the Communist Party in December, 1925, Zinoviev spoke up for others on the left when he declared: "There exists within the Party a most dangerous right deviation. It lies in the underestimation of the danger from the kulak - the rural capitalist. The kulak, uniting with the urban capitalists, the NEP men, and the bourgeois intelligentsia will devour the Party and the Revolution." (85) However, when the vote was taken, Stalin's policy was accepted by 559 to 65. (86)

In September 1926 Stalin threatened the expulsion of Yuri Piatakov, Leon Trotsky, Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, Mikhail Lashevich and Grigori Sokolnikov. On 4th October, these men signed a statement admitting that they were guilty of offences against the statutes of the party and pledged themselves to disband their party within the party. They also disavowed the extremists in their ranks who were led by Alexander Shlyapnikov. However, having admitted their offences against the rules of discipline, they "restated with dignified firmness their political criticisms of Stalin and Bukharin." (87)

Stalin appointed his old friend, Gregory Ordzhonikidze, to the presidency of the Central Control Commission in November 1926, where he was given responsibility for expelling the Left Opposition from the Communist Party. Ordzhonikidze was rewarded by being appointed to the Politburo in 1926. He developed a reputation for having a terrible temper. His daughter said that he "often got so heated that he slapped his comrades but the eruption soon passed." His wife Zina argued "he would give his life for one he loved and shoot the one he hated". However, others said he had great charm and Maria Svanidze described him as "chivalrous". The son of Lavrenty Beria commented that his "kind eyes, grey hair and big moustache, gave him the look of an old Georgian prince". (88)

Stalin gradually expelled his opponents from the Politburo including Trotsky, Zinoviev and Lashevich. He also appointed his allies, Vyacheslav Molotov, Kliment Voroshilov, Gregory Ordzhonikidze, Lazar Kaganovich, Sergy Kirov, Semen Budenny and Andrei Andreev. "He demanded efficiency as well as lyalty from the gang members... He wanted no one near to him who outranked him intellectually. He selected men with a revolutionary commitment like his own, and he set the style with his ruthless policies... In return for their services he looked after their interests. He was solicitous about their health. He overlooked their foibles so long as their work remained unaffected and the recognised his word as law." (89)

Kaganovich later recalled: In the early years Stalin was a soft individual... Under Lenin and after Lenin. He went through a lot. In the early years after Lenin died, when he came to power, they all attacked Stalin. He endured a lot in the struggle with Trotsky. Then his supposed friends Bukharin, Rykov and Tomsky also attacked him... It was difficult to avoid getting cruel." (90)

In the spring of 1927 Trotsky drew up a proposed programme signed by 83 oppositionists. He demanded a more revolutionary foreign policy as well as more rapid industrial growth. He also insisted that a comprehensive campaign of democratisation needed to be undertaken not only in the party but also in the soviets. Trotsky added that the Politburo was ruining everything Lenin had stood for and unless these measures were taken, the original goals of the October Revolution would not be achievable. (91)

Stalin and Bukharin led the counter-attacks through the summer of 1927. At the plenum of the Central Committee in October, Stalin pointed out that Trotsky was originally a Menshevik: "In the period between 1904 and the February 1917 Revolution Trotsky spent the whole time twirling around in the company of the Mensheviks and conducting a campaign against the party of Lenin. Over that period Trotsky sustained a whole series of defeats at the hands of Lenin's party." Stalin added that previously he had rejected calls for the expulsion of people like Trotsky and Zinoviev from the Central Committee. "Perhaps, I overdid the kindness and made a mistake." (92)

According to Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996): "The opposition then organized demonstrations in Moscow and Leningrad on November 7. These were the last two open demonstrations against the Stalinist regime. The GPU, of course, knew about them in advance but allowed them to take place. In Lenin's Party submitting Party differences to the judgment of the crowd was considered the greatest of crimes. The opposition had signed their own sentence. And Stalin, of course, a brilliant organizer of demonstrations himself, was well prepared. On the morning of November 7 a small crowd, most of them students, moved toward Red Square, carrying banners with opposition slogans: Let us direct our fire to the right - at the kulak and the NEP man, Long live the leaders of the World Revolution, Trotsky and Zinoviev.... The procession reached Okhotny Ryad, not far from the Kremlin. Here the criminal appeal to the non-Party masses was to be made, from the balcony of the former Paris hotel. Stalin let them get on with it. Smilga and Preobrazhensky, both members of Lenin's Central Committee, draped a streamer with the slogan Back to Lenin over the balcony." (93)

Stalin argued that there was a danger that the party would split into two opposing factions. If this happened, western countries would take advantage of the situation and invade the Soviet Union. On 14th November 1927, the Central Committee decided to expel Leon Trotsky and Gregory Zinoviev from the party. This decision was ratified by the Fifteenth Party Congress in December. The Congress also announced the removal of another 75 oppositionists, including Lev Kamenev. (94)

The Russian historian, Roy A. Medvedev, has explained in Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism (1971): "The opposition's semi-legal and occasionally illegal activities were the main issue at the joint meeting of the Central Committee and Central Control Commission at the end of October, 1927... The Plenum decided that Trotsky and Zinoviev had broken their promise to cease factional activity. They were expelled from the Central Committee, and the forthcoming XVth Congress was directed to review the whole issue of factions and groups." Under pressure from the Central Committee, Kamenev and Zinoviev agreed to sign statements promising not to create conflict in the movement by making speeches attacking official policies. Trotsky refused to sign and was banished to the remote area of Kazhakstan. (95)

One of Trotsky's main supporters, Adolf Joffe, was so disillusioned by these events that he committed suicide. In a letter he wrote to Trotsky before his death, he commented: "I have never doubted the rightness of the road you pointed out, and as you know, I have gone with you for more than twenty years, since the days of permanent revolution. But I have always believed that you lacked Lenin unbending will, his unwillingness to yield, his readiness even to remain alone on the path that he thought right in the anticipation of a future majority, of a future recognition by everyone of the rightness of his path... One does not lie before his death, and now I repeat this again to you. But you have often abandoned your rightness for the sake of an overvalued agreement or compromise. This is a mistake. I repeat: politically you have always been right, and now more right than ever... You are right, but the guarantee of the victory of your rightness lies in nothing but the extreme unwillingness to yield, the strictest straightforwardness, the absolute rejection of all compromise; in this very thing lay the secret of Lenin's victories. Many a time I have wanted to tell you this, but only now have I brought myself to do so, as a last farewell." (96)

Collective Farms

Stalin now decided to turn on the right-wing of the Politburo. He blamed the policies of Nickolai Bukharin for the failure of the 1927 harvest. By this time kulaks made up 40% of the peasants in some regions, but still not enough food was being produced. On 6th January, 1928, Stalin sent out a secret directive threatening to sack local party leaders who failed to apply "tough punishments" to those guilty of "grain hoarding". By the end of the year it was revealed that food production had been two million tons below that needed to feed the population of the Soviet Union. (97)

During that winter Stalin began attacking kulaks for not supplying enough food for industrial workers. He also advocated the setting up of collective farms. The proposal involved small farmers joining forces to form large-scale units. In this way, it was argued, they would be in a position to afford the latest machinery. Stalin believed this policy would lead to increased production. However, the peasants liked farming their own land and were reluctant to form themselves into state collectives. (98)

Stalin was furious that the peasants were putting their own welfare before that of the Soviet Union. Local communist officials were given instructions to confiscate kulaks property. This land was then used to form new collective farms. There were two types of collective farms introduced. The sovkhoz (land was owned by the state and the workers were hired like industrial workers) and the kolkhoz (small farms where the land was rented from the state but with an agreement to deliver a fixed quota of the harvest to the government). He appointed Vyacheslav Molotov to carry out the operation. (99)

In December, 1929, Stalin made a speech at the Communist Party Congress. He attacked the kulaks for not joining the collective farms. "Can we advance our socialised industry at an accelerated rate while we have such an agricultural basis as small-peasant economy, which is incapable of expanded reproduction, and which, in addition, is the predominant force in our national economy? No, we cannot. Can Soviet power and the work of socialist construction rest for any length of time on two different foundations: on the most large-scale and concentrated socialist industry, and the most disunited and backward, small-commodity peasant economy? No, they cannot. Sooner or later this would be bound to end in the complete collapse of the whole national economy. What, then, is the way out? The way out lies in making agriculture large-scale, in making it capable of accumulation, of expanded reproduction, and in thus transforming the agricultural basis of the national economy." (100)

Stalin then went on to define kulaks as "any peasant who does not sell all his grain to the state". Those peasants who were unwilling to join collective farms "must be annihilated as a class". As the historian, Yves Delbars, pointed out: "Of course, to annihilate them as a social class did not mean the physical extinction of the kulaks. But the local authorities had no time to draw the distinction; moreover, Stalin had issued stringent orders through the agricultural commission of the central committee. He asked for prompt results, those who failed to produce them would be treated as saboteurs." (101)

Local communist officials were given instructions to confiscate kulak property. This land would then be used to form new collective farms. The kulaks themselves were not allowed to join these collectives as it was feared that they would attempt to undermine the success of the scheme. An estimated five million were deported to Central Asia or to the timber regions of Siberia, where they were used as forced labour. Of these, approximately twenty-five per cent perished by the time they reached their destination. (102) According to the historian, Sally J. Taylor: "Many of those exiled died, either along the way or in the makeshift camps where they were dumped, with inadequate food, clothing, and housing." (103)

Ian Grey, in his book, Stalin: Man of History (1982): "The peasants demonstrated the hatred they felt for the regime and its collectivisation policy by slaughtering their animals. To the peasant his horse, his cow, his few sheep and goats were treasured possessions and a source of food in hard times... In the first months of 1930 alone 14 million head of cattle were killed. Of the 34 million horses in the Soviet Union in 1929, 18 million were killed, further, some 67 per cent of sheep and goats were slaughtered between 1929 and 1933." (104)

Walter Duranty, a journalist working for the New York Times, observed the suffering caused by collectivisation: "At the windows haggard faces, men and women, or a mother holding her child, with hands outstretched for a crust of bread or a cigarette. It was only the end of April but the heat was torrid and the air that came from the narrow windows was foul and stifling; for they had been fourteen days en route, not knowing where they were going nor caring much. They were more like caged animals than human beings, not wild beasts but dumb cattle, patient with suffering eyes. Debris and jetsam, victims of the March to Progress." (105)

Riots broke out in several regions and Joseph Stalin, fearing a civil war, and peasants threatening not to plant their spring crop, called a halt to collectivisation. During 1930 this policy led to 2,200 rebellions involving more than 800,000 people. Stalin wrote an article for Pravda attacking officials for being over-zealous in their implementation of collectivisation. "Collective farms," Stalin wrote, "cannot be set up by force. To do so would be stupid and reactionary." (106)

Stalin portrayed himself in the article as the protector of the peasants. Members of the Politburo and local officials were upset that they had been blamed for a policy that had been devised by Stalin. The man who was mainly responsible for the peasants' suffering was now seen as their hero. It was reported that as peasants marched in procession out of their collective farms to return to their own land, they carried large pictures of their saviour, "Comrade Stalin". Within three months of Stalin's article appearing, the numbers of peasants in collective farms dropped from 60 to 25 per cent. It was clear that if Stalin wanted collectivisation, he could not allow freedom of choice. Once again Stalin ordered local officials to start imposing collectivisation. By 1935, 94 per cent of crops were being produced by peasants working on collective farms. The cost to the Soviet people was immense. As Stalin was to admit to Winston Churchill, approximately ten million people died as a result of collectivisation. (107)

Five Year Plan

Leon Trotsky, Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev and other left-wing members of the Politburo had always been in favour of the rapid industrialisation of the Soviet Union. Stalin disagreed with this view. He accused them of going against the ideas of Lenin who had declared that it was vitally important to "preserve the alliance between the workers and the peasants." When left-wing members of the Politburo advocated the building of a hydro-electric power station on the River Druiper, Stalin accused them of being 'super industrialisers' and said that it was equivalent to suggesting that a peasant buys a "gramophone instead of a cow." (108)

When Stalin accepted the need for collectivisation he also had to change his mind about industrialisation. His advisers told him that with the modernisation of farming the Soviet Union would require 250,000 tractors. In 1927 they had only 7,000. As well as tractors, there was also a need to develop the oil fields to provide the necessary petrol to drive the machines. Power stations also had to be built to supply the farms with electricity.

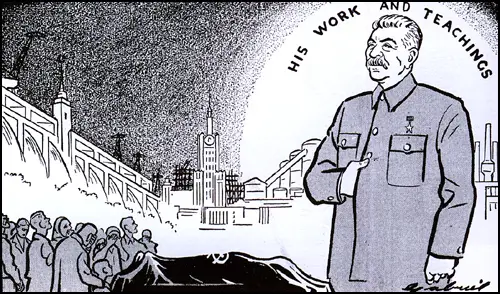

However, Stalin suddenly changed policy and made it clear he would use his control over the country to modernize the economy. The first Five Year Plan that was introduced in 1928, concentrated on the development of iron and steel, machine-tools, electric power and transport. Stalin set the workers high targets. He demanded a 111% increase in coal production, 200% increase in iron production and 335% increase in electric power. He justified these demands by claiming that if rapid industrialization did not take place, the Soviet Union would not be able to defend itself against an invasion from capitalist countries in the west. (109)

The first Five-Year Plan did not get off to a successful start in all sectors. For example, the production of pig iron and steel increased by only 600,000 to 800,000 tons in 1929, barely surpassing the 1913-14 level. Only 3,300 tractors were produced in 1929. The output of food processing and light industry rose slowly, but in the crucial area of transportation, the railways worked especially poorly. "In June, 1930, Stalin announced sharp increases in the goals - for pig iron, from 10 million to 17 million tons by the last year of the plan; for tractors, from 55,000 to 170,000; for other agricultural machinery and trucks, an increase of more than 100 per cent." (110)

Every factory had large display boards erected that showed the output of workers. Those that failed to reach the required targets were publicity criticized and humiliated. Some workers could not cope with this pressure and absenteeism increased. This led to even more repressive measures being introduced. Records were kept of workers' lateness, absenteeism and bad workmanship. If the worker's record was poor, he was accused of trying to sabotage the Five Year Plan and if found guilty could be shot or sent to work as forced labour on the Baltic Sea Canal or the Siberian Railway. (111)

One of the most controversial aspects of the Five Year Plan was Stalin's decision to move away from the principle of equal pay. Under the rule of Lenin, for example, the leaders of the Bolshevik Party could not receive more than the wages of a skilled labourer. With the modernization of industry, Stalin argued that it was necessary to pay higher wages to certain workers in order to encourage increased output. His left-wing opponents claimed that this inequality was a betrayal of socialism and would create a new class system in the Soviet Union. Stalin had his way and during the 1930s, the gap between the wages of the labourers and the skilled workers increased. (112)

According to Bertram D. Wolfe, during this period Russia had the most highly concentrated industrial working class in Europe. "In Germany at the turn of the century, only fourteen per cent of the factories had a force of more than five hundred men; in Russia the corresponding figure was thirty-four per cent. Only eight per cent of all German workers worked in factories employing over a thousand working men each. Twenty-four per cent, nearly a quarter, of all Russian industrial workers worked in factories of that size. These giant enterprises forced the new working class into close association. There arose an insatiable hunger for organization, which the huge state machine sought in vain to direct or hold in check." (113)

Joseph Stalin now had a problem of workers wanting to increase their wages. He had a particular problem with unskilled workers who felt they were not being adequately rewarded. Stalin insisted on the need for a highly differentiated scale of material rewards for labour, designed to encourage skill and efficiency and "throughout the thirties, the differentiation of wages and salaries was pushed to extremes, incompatible with the spirit, if not the letter, of Marxism." (114)

Stalin gave instructions that concentration camps should not just be for social rehabilitation of prisoners but also for what they could contribute to the gross domestic product. This included using forced labour for the mining of gold and timber hewing. Stalin ordered Vladimir Menzhinski, the chief of the OGPU, to create a permanent organisational framework that would allow for prisoners to contribute to the success of the Five Year Plan. People sent to these camps included members of outlawed political parties, nationalists and priests. (115)

Robert Service, the author of Stalin: A Biography (2004), has pointed out: "During the First Five Year Plan the USSR underwent drastic change. Ahead lay campaigns to spread collective farms and eliminate kulaks, clerics and private traders. The political system would become harsher. Violence would be pervasive. The Russian Communist Party, OGPU and People's Commissariat would consolidate their power. Remnants of former parties would be eradicated… The Gulag, which was the network of labour camps subject to the People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD), would be expanded and would become an indispensable sector of the Soviet economy… A great influx of people from the villages would take place as factories and mines sought to fill their labour forces. Literacy schemes would be given huge state funding… Enthusiasm for the demise of political, social and cultural compromise would be cultivated. Marxism-Leninism would be intensively propagated. The change would be the work of Stalin and his associates in the Kremlin. Theirs would be the credit and theirs the blame." (116)

Eugene Lyons was an American journalist who was fairly sympathetic to the Soviet government. On 22nd November, 1930, Stalin selected him to be the first western journalist to be granted an interview. Lyons claimed that: "One cannot live in the shadow of Stalin's legend without coming under its spell. My pulse, I am sure, was high. No sooner, however, had I stepped across the threshold than diffidence and nervousness fell away. Stalin met me at the door and shook hands, smiling. There was a certain shyness in his smile and the handshake was not perfunctory. He was remarkably unlike the scowling, self-important dictator of popular imagination. His every gesture was a rebuke to the thousand little bureaucrats who had inflicted their puny greatness upon me in these Russian years.... At such close range, there was not a trace of the Napoleonic quality one sees in his self-conscious camera or oil portraits. The shaggy mustache, framing a sensual mouth and a smile nearly as full of teeth as Teddy Roosevelt's, gave his swarthy face a friendly, almost benignant look." (117)

Walter Duranty was furious when he heard that Stalin had granted Lyons this interview. He protested to the Soviet Press office that as the longest-serving Western correspondent in the country it was unfair not to give him an interview as well. A week after the interview Duranty was also granted an interview. Stalin told him that after the Russian Revolution the capitalist countries could have crushed the Bolsheviks: "But they waited too long. It is now too late." Stalin commented that the United States had no choice but to watch "socialism grow". Duranty argued that unlike Leon Trotsky Stalin was not gifted with any great intelligence, but "he had nevertheless outmaneuvered this brilliant member of the intelligentsia". He added: "Stalin has created a great Frankenstein monster, of which... he has become an integral part, made of comparatively insignificant and mediocre individuals, but whose mass desires, aims, and appetites have an enormous and irresistible power. I hope it is not true, and I devoutly hope so, but it haunts me unpleasantly. And perhaps haunts Stalin." (118)