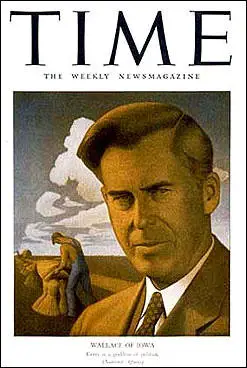

Henry Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace, the son of Henry Cantwell Wallace and May Brodhead, was born near the town of Orient in Adair County, on 7th October, 1888. His father raised shorthorn cattle, Poland China hogs, Percheron horses on his farm. Carter found life difficult as the prices for cattle and hogs was falling dramatically. After the birth of their second child, Annabelle in 1891, Wallace began considering giving up farming. In 1892 he accepted a position the position of "professor of agriculture" at the Iowa State Agricultural College in Ames.

Wallace was not sent to school and had very few friends as a child, but did develop a close relationship with George Washington Carver, one of his father's students. Carver, born into slavery in M in 1864, was fascinated by plants. Wallace later recalled that Carver "took a fancy to me and took me with him on his botanizing expeditions and pointed out to me the flowers and the parts of flowers - the stamens and the pistil. I remember him claiming to my father that I had greatly surprised him by recognizing the pistils and stamens of redtop, a kind of grass... I also remember rather questioning his accuracy in believing that I recognized these parts, but anyhow he boasted about me, and the mere fact of his boasting, I think, incited me to learn more than if I had really done what he said I had done."

Henry Cantwell Wallace

Henry Cantwell Wallace, like his father, was interested in agricultural journalism. Together with a fellow faculty member, Charles F. Curtiss, he purchased the Iowa Farmer and Breeder , a small livestock journal published twice a month. After taking control of it they changed its name to Farm and Dairy . In 1894 he created a great deal of controversy by questioning the integrity and scientific findings of a well-known local chemist. As a result of the article Wallace was forced to resign from the Iowa State Agricultural College.

Wallace's father was also having problems. James Pierce, the publisher of Iowa Homestead , objected to his anti-monoploy stance. He was also ordered to write favorable stories about a Chicago's firm agricultural products. Wallace Snr. later discovered that this was in return for a lucrative advertising contract. When he resisted these orders he was fired as editor of the journal. Henry Wallace, almost sixty years old, and his son were both without jobs.

It was eventually decided to join forces to publish a new journal, Wallaces' Farm and Dairy . In the first edition on 18th September, 1896, Henry Cantwell Wallace explained the background to the venture: "Mr. Wallace was for ten years, up to February 1895, the editor of the Iowa Homestead . His withdrawal from the paper was the culmination of trouble between him and the business manager as to its public editorial policy, Mr. Wallace wishing to maintain it in its old position as the leading western exponent of anti-monopoly principles. Failing in this he became the editor of the Farm and Diary, over the editorial policy of which he has full control."

John C. Culver, the author of American Dreamer: A Life of Henry A. Wallace (2001), has pointed out: "Henry A. Wallace's salient characteristic was his curiosity. He craved to know things...When he was a boy, his curiosity expressed itself mainly in the realm of plants... When the family moved to a house on Des Moines's western edge, ten-year-old Henry's first act was to secure a portion of the property for his own use. There he established an elaborate garden and grew enough tomatoes, cabbages, and celery to feed the family.... Starting about the time he entered West High School at fourteen, and continuing for almost three decades, corn was the dominating aspect of Henry A. Wallace's life. Corn became his passion, his cause, the medium of his genius. He knew corn as well as he knew people."

In December 1898 Henry Cantwell Wallace changed the name of his journal to Wallaces' Farmer . He added a credo that summed up in six words what they and their paper stood for: "Good farming, clear thinking, right living." According to one source: "There was a page devoted to news about hogs, a page for diary farmers, a horticulture page, a market page, and... a page sprinkled with inspirational poems, recipes, and housemaking tips."

Within two years of its founding the newspaper had around 20,000 paying subscribers. After five years they had replaid all their debts and Henry and his father were receiving good salaries. They also moved into a modern building in downtown Des Moines. By 1902 Henry Wallace had enough money to buy ten acres on the west side and was able to construct a new home that cost more than $5,000. Ten years later he purchased a brick mansion that cost over $50,000.

Early Life of Henry Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace later recalled that his father played a very small role in his daily life. He said that he could barely remember a time during his youth when his father was not working. However, he did spend a great deal of his grandfather, who was now in his seventies and had retired from the growing publishing business. He remembered taking all-day buggy trips where they would discuss agriculture and religion.

In January 1904 Wallace, aged 15, attended a course of lectures by Perry G. Holden, the vice-dean of agriculture at Iowa State University. Wallace later wrote: "No man ever engaged in more rapid and effective mass education of farmers than did P.G. Holden from 1902 to 1910 in Iowa." Holden's main thesis was that the good appearance reflected good quality. Despite his young age, Wallace questioned Holden's ideas. His biographer, John C. Culver, has pointed out: "It was remarkable: a reserved teenager challenging an eminent expert on the very grounds of his expertise... From an early age, and for the remainder of his life, a central characteristic of Henry A. Wallace's personality was independence of mind. He was open to any idea, however silly sounding, until he could test its validity. He was prepared to reject any idea, no matter how broadly accepted, that would not stand the weight of inquiry."

Holden gave Wallace several ears of corn on display and told him to use them for seed. He said that if he carried out a scientific experiment he would discover the finest-looking corn would produce the largest yield and the worst-looking corn the smallest. That spring he persuaded his father to let him use five acres of land behind their home. After harvesting that year he was was able to show that holden's theory was wrong. The ears of fine yellow dent corn Holden had given him ranged in yield from 33 to 79 bushels an acre. Some of the best-yielding ears were those Holden had judged to be the poorest. The ear that Holden had singled out as the most beautiful of all was one of the ten worst in yield.

Iowa Agricultural College

Wallace left West High School for Iowa State Agricultural College in Ames in 1906. Professor J.L. Lush claimed that "he (Wallace) was healthily skeptical of many things he was taught in class and was constantly challenging them." A fellow student commented: "He always wanted to know why and could spend considerable time discussing some particular matter with a teacher. He was always a thinker... He was half a jump ahead of the instructors in some classes."

Wallace continued to carry out experiments. After reading a magazine article on fasting by Upton Sinclair, he decided to try it out: "I thought I'd try it out. I walked, I suppose, two or three miles a day and carried on my studies. It's amazing how much time you can pick up if you don't eat." However, he went too long without food and developed "rather an abnormal state of mind" and was forced to bring an end to his starvation diet.

In the summer of 1909 Wallace began producing material for his father's Wallaces' Farmer. His first project was a three month tour of the American West, from the dusty plains of Texas to the great agricultural valleys of California. He traveled mainly by train and at each place he visited he produced an article on the state of its agriculture. He was paid by the inch and earned enough to pay his college expenses during the next year.

Wallace's senior thesis, a forty-page treatise entitled Live Stock Farming and the Fertility of the Soil , was a call for progressive reform. He warned that soil conservation was a problem of national proportions and argued that the federal government needed to become involved in protecting this vital resource. "We have our choice between that and ruin."

After leaving college Wallace worked full-time on the Wallaces Farmer. He became a strong supporter of Gifford Pinchot who was put in charge of the United States Forest Service. In 1912 Presidential Election Wallace considered the two main candidates, Woodrow Wilson of the Democratic Party and William Taft of the Republican Party, as too conservative and gave his support to third-party candidate Theodore Roosevelt.

Wallace took a close interest in the economics of agriculture. He later wrote: "I learned how to calculate correlation coefficients and came to have a very great respect for quantitative methods of economic analysis." Wallaces Farmer routinely published complicated graphs exploring trends in commodity prices and reports on scientific work being carried out on improving the quality of corn or livestock.

Thorstein Veblen

In 1913 Wallace read The Theory of the Leisure Class by Thorstein Veblen. The book attempted to apply Darwin's theory of evolution to the modern economy. Veblen argued that the dominant class in capitalism, which he labelled as the "leisure class", pursued a life-style of "conspicuous consumption, ostentatious waste and idleness". He also upset the academic world when he claimed that higher learning was marked by "conspicuous consumption".

Wallace also read Veblen's book, The Theory of Business Enterprise (1904), that looked at what he believed was the incompatibility between the behaviour of the capitalist with the modern industrial process. Veblen argued that the new industrial processes impelled integration and provided lucrative opportunities for those who managed it. Veblen believed this resulted in a conflict between businessmen and engineers.

Wallace was very impressed with Veblen's work and argued that his "books were among "the most powerful produced in the United States in this century". He arranged a meeting with Veblen and later recalled that he found him "a mousy kind of man... not a particularly attractive person." However, he was "dazzled by his brilliant mind" and was deeply influenced by his views on capitalism, nationalism and militarism. Wallace observed that the economist was one of the few men who really "knew what was going on". Wallace admitted that Veblen "had a marked effect on my economic thinking."

Marriage

Henry Wallace met Ilo Browne at a picnic in Des Moines in 1913. She had been left a substantial sum of money by her father who had died two years earlier. One of her friends recalled: "Henry Wallace was on her trail every minute. He used to take Ilo driving in a dilapidated old car. Money never meant a thing to Henry, and his eccentricity didn't matter to Ilo." They were married on 20th May, 1914 and they went to live on a 40 acre farm near Johnson County.

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 created serious problems for farmers in Europe. To survive, the countries involved in the conflict had to increase its imports of food. This increased prices and profits. Wallace wrote in his newspaper in 1916: "Dare we assume that the great Ruler plunges half the world into war, that the other half may profit by the manufacture of war materials and the growing of foodstuffs? Who are we, and what have we done, that material blessings should be showered upon us so lavishly?" Wallace also warned about what might happen to agricultural in the years to follow: "Ultimately the United States will have to bear its share of the burden of this war, but very likely for a year, and possibly for two or three years, after the war ends, we will continue on the high tide of prosperity, to be followed by a depression lasting for a number of years... Now would be a good time to reduce your debts."

(If you find this article useful, please feel free to share. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.)

On the death of his grandfather, Henry Wallace, Sr., in February 1916, Wallace became joint editor with his father, Henry Cantwell Wallace, on the Wallaces Farmer. He had been inspired by his grandfather to devote his life to the community. Russell Lord, the author of The Wallaces of Iowa (1947), has pointed out: "We know that his great desire was that in his descendants should be multiplied his power for good; that they should live worthily; that they should keep untarnished the family name which he so jealously guarded; that they should always and everywhere be men and women whom he could honor and respect that they should carry on the work which he began."

First World War

On 2nd April 1917, President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. Wallace reluctantly gave his support to America's involvement in the First World War. On the 6th April he wrote: "At the bottom, this whole business is a struggle to maintain the ideals upon which this great American republic was founded, and for which, when the pinch comes, are always ready to fight. Emperors fight for commercial supremacy, for extension of their domain, for their right to rule. Democracies fight for human liberty, for the rights of man.

In May 1917 Wallace decided to carry out another experiment on himself. He decided to try living on 30 cents a day. His diet included eating only corn, dairy products plus an occasional radish or bite of lettuce. His father wrote in Wallaces Farmer, "he has maintained his weight, feels in perfect health, and has carried on his work both on the farm and in the office with entire comfort."

In his newspaper Henry Cantwell Wallace urged President Wilson to take action to protect agriculture. In August, 1917, Wilson responded by appointing Herbert Hoover to head the recently created Office of Food Administration. Hoover was aware that there was a shortage of fat in the European diet. He thought the best way to solve this problem was to increase the export of pork to Europe. Farmers were reluctant to invest in breeding hogs because of the low prices they were commanding at market.

Herbert Hoover

In October 1917 Hoover decided to establish a Swine Commission to look at methods to persuade farmers to increase hog production. He invited Henry A. Wallace and Henry Cantwell Wallace to join the commission. In its report it suggested that the government guarantee the price of hogs at a rate of return of at least 14.3 to 1 (the price of 14.3 bushels of corn would equal 100 pounds of live hog). Hoover rejected the idea but in November he established the minimum price as 13 to 1. Wallace denounced the Food Administration's position as "illogical, unjust and ridiculous". Hoover wrote to Wallace explaining his position. Wallace replied that "hog farmers needed profits, not carefully crafted words."

This began a long-drawn out conflict between Herbert Hoover and the Wallace family. In February 1920, an editorial in the Wallaces Farmer condemned Hoover for trying "to bamboozle the farmers" and expressing the opinion that he was denying farmers the ability to make a reasonable profit: "If we were asked to name one man who is more responsible than any other for starting the dissatisfaction which exists among the farmers of the country, we would instantly name Mr. Hoover." Hoover tried several times to make his peace with Wallace but he refused to back-down. As his friend, Gifford Pinchot, pointed out: "Wallace was a natural-born gamecock. He was red-headed on his head and in his soul."

In 1920 William Squire Kenyon recommended Henry Cantwell Wallace to the Republican Party presidential nominee, Warren Harding. Kenyon wrote: "The best man I know of in the whole United States, with reference to agriculture is Mr. Henry Wallace. He is a sturdy Scotchman, staunch, level-headed, and knows agricultural problems." Wallace advised Harding throughout the campaign and was considered to be an important factor in his victory. As expected, Wallace was appointed as Secretary of Agriculture. He told his readers: "I will do the best I know."

Editor of Wallaces Farmer

Henry A. Wallace now had full control over Wallaces Farmer. Over the next few months Wallace suggested solutions to the agricultural depression that he had predicted during the First World War. Wallace argued that the only way to increase the price of corn was to reduce production. He told his readers that they should take 10 per cent of their land out of corn production and cover it with a nitrogen-building legume such as clover. The resulting drop in supply would increase prices and enrich both farmers and their land: "After everything has been taken into account, the fact remains that we have far more corn than we need."

Wallace also suggested a government-operated storage system. He got the idea from a book written by Chen Huan-chang, that described a grain storage system established in China in 54 B.C. "When the price of grain was low, the province should buy it at the normal price, higher than the market price, in order to profit the farmers. When the price was high, they should sell it at the normal price, lower than the market price, in order to profit the customers." The book explained that the storage system survived in various forms for fourteen hundred years. Wallace urged the government to take similar action: "If any government shall ever do anything really worth while with our food problem it will be by perfecting the plan tried by the Chinese 2,000 years ago; that is, by building warehouses and storing food in years of abundance and holding it until the years of scarcity."

Wallace remained a passionate supporter of agricultural scientific advancement: He wrote: "A revolution in corn breeding is coming which will affect every man, woman and child in the corn belt within 20 years. Our systems of farm management will be changed somewhat and it is even possible that both domestic policies and the foreign relations of the United States will be somewhat influenced." Wallace's main area of interest was the development of hybrid corn. In 1923, George Kurtzweil of the Iowa Seed Company in Des Moines, agreed to sell Wallace's Copper Cross seed. In the first year the new seed brought in only $840.

Henry Cantwell Wallace also developed his own plan to solve the economic crisis in agriculture. He approached Senator Charles L. McNary of Oregon and Representative Gilbert N. Haugen of Iowa to serve as the sponsors of his plan. This eventually became known as the McNary-Haugen Farm Relief Bill that proposed a federal agency would support and protect domestic farm prices by attempting to maintain price levels that existed before the First World War. It was argued that by purchasing surpluses and selling them overseas, the federal government would take losses that would be paid for through fees against farm producers. The bill was passed by Congress in 1924 but was vetoed by President Calvin Coolidge.

Wallace in the Wallaces Farmer had campaigned strongly for McNary-Haugen bill. He wrote that politicians were "willing to entertain a feeling of sympathy for farmers who are having a hard time, provided that sympathy costs them nothing and further provided that they are not asked to cease worshiping at the shrine of laissez-faire." President Coolidge was very angry with his Secretary of Agriculture but was warned against sacking a man who was so popular with farmers at a time when the presidential election was less than a year away.

Henry Cantwell Wallace went into hospital for the removal of his gall bladder. The operation took place on 15th October, 1924. It was deemed a success and was working from his hospital bed when he became seriously ill. His doctor diagnosed the problem as toxemic poisoning and he died on 25th October. He was 58 years old at the time of his death.

Wallace wrote in the next edition of the Wallaces Farmer: "The fight for agricultural equality will go on; so will the battle for a stable price level, for controlled production, for better rural schools and churches, for larger income and higher standards of living for the working farmers, for the checking of speculation in farm lands, for the thousand and one things that are needed to make the sort of rural civilization he labored for and hoped to see. He died with his armor on in the fight for the cause which he loved."

The Progressive Party

Wallace had always supported the Republican Party but was highly critical of the lack of action of Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge. In the 1924 Presidential Election he urged the readers of Wallaces Farmer to vote for Robert LaFollette and his Progressive Party. Coolidge won the election with 15.7 million votes. John W. Davis of the Democratic Party received only 8.4 million. LaFollette only obtained 4.8 million votes and carried only his home state of Wisconsin.

James D. LeCron, a close friend of Wallace, pointed out he lacked social skills: "Lots of people didn't like him because he wasn't a free and easy sort. At the same time, he was very modest and there was nothing cocky about him." John C. Culver added: "There was something vaguely suspect about Wallace's unconventional thought, and his progressive politics grated on Republican sensibilities... High-minded and cerebral, reserved to the point of shyness, Wallace did not make conversation freely."

Herbert Hoover was chosen as the Republican Party candidate for the 1928 Presidential Election. Wallace told his readers that Hoover had betrayed farmers before and that if they wanted the McNary-Haugen Farm Relief Bill to be passed, they had to make sure Hoover was defeated. Wallace was not enthusiastic about the Democratic Party candidate Al Smith and suggested that farmers should consider forming a "new party" with roots in rural America.

In 1929 Wallace established the Hi-bred Corn Company. It was advertised with the slogan: "Our new system of picking seed ears only from detassled plants produces a vigorous, high yielding, high grade, only maturing corn." Roswell Garst joined the company and an excellent salesman, he managed to persuade large numbers of farms in Iowa to buy their hybred corn seed.

The Great Depression

Wallace had predicted the Great Depression and in 1930 he wrote a sixteen-page pamphlet, Causes of the World Wide Depression , explaining what happened. He suggested three major causes: (1) Technological changes that had resulted in a surplus of goods and lower prices; (2) Large war debts combined with high tariffs had damaged world trade; (3) The unwillingness of central banks to increase money supplies that had led to long-term deflation.

The economic downturn caused problems for Wallaces Farmer. Some farmers could no longer afford to purchase the newspaper. Existing staff were laid off and in an effort to cut costs it changed from a weekly to a biweekly publication. Wallace even let farmers pay their yearly subscription in chickens. Wallace approached Wall Street financier Bernard Baruch for help. He later recalled: "He (Baruch) said what a shame it was to see young fellows be ruined, but he wasn't interested." Wallace was forced to sell the publication to Dante Pierce but agreed to remain as editor.

Wallace continued to express his dissatisfaction with the two main political parties. He told a friend: "I am just as much disgusted with the Democrats as I am with the Republicans and would like to see the destruction of both the old parties." Another friend suggested he join the Socialist Party of America. Wallace replied: "I don't like the spirit of many of the socialists. It seems to me that they derive their strength too much by mere opposition to the existing order. I would like to see a sweeter spirit on the parts of the socialists."

The Great Depression hit the farming community in Iowa very hard. The price of corn fell so low that farmers burned it to keep warm instead of bothering to take it to market. Total farm income fell by two-thirds between 1929 and 1932. Six of every ten farms had to be re-mortgaged and in 1932, five out of every one hundred farms in the state were foreclosed and sold at auction. Wallace told his readers that the "cure is simply that a greater percentage of the income of the nation be turned back to the mass of the people."

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Wallace thought that President Herbert Hoover had been a disaster and was tempted for the first time to support the Democratic Party. He was initially suspicious of Franklin D. Roosevelt: "I thought he was just a typical easterner who didn't know too much about the west or other practical affairs - that is, the way ordinary people live." Roosevelt had already identified Wallace as a possible influencial supporter and sent his friend, Henry Morgenthau, to see him. Wallace later recalled that Morgenthau was "a very nice fellow, rather bashful and diffident" but who was "exceedingly weak and tender physically". He added: "I've met very few people who impressed me as being so lacking in physical sturdiness."

Wallace agreed to join Roosevelt's team of advisors on agriculture. This included Rexford Tugwell, George N. Peek and Hugh S. Johnson. Wallace and Tugwell were both impressed with a plan put foward by M. L. Wilson, a professor of agricultural economics at Montana State Agricultural College. Wilson's idea was called the domestic allotment plan. Farmers who agreed to limit production would be rewarded with "allotment payments" which would supplement the income they received for crops on the open market. Its main purpose was not to subsidize farmers but to control production.

Tugwell arranged for Wallace to meet Roosevelt at his home, Hyde Park, on 13th August. Wallace later recalled: "I had heard that his legs were paralyzed, and I feared that he would be completely tired out." Instead he found "a man with a fresh, eager, open mind, ready to pitch into the agricultural problem at once... He knows that he doesn't know it all, and tries to find out all he can from people who are supposed to be authorities." Wallace spent two hours with Roosevelt: "We didn't discuss the election or the campaign at all. No politics, as such, came up at all that day."

In September, 1932, Wallace and M. L. Wilson wrote the first draft of Roosevelt's speech where he gave his support to the domestic allotment plan. By the time the speech was delivered in Topeka it was more vague than Wallace had hoped. However, it still included the promise to raise farm prices without stimulating production. Wallace continued to advocate the plan in Wallaces' Farmer and denounced Herbert Hoover as the most dangerous man in America. "The only thing to vote for in this election is justice for agriculture. With Roosevelt, the farmers have a chance - with Hoover, none. I shall vote for Roosevelt."

Although Franklin D. Roosevelt was vague about what he would do about the economic depression, he easily beat his unpopular Republican rival. William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963), has argued: "Franklin Roosevelt swept to victory with 22,800,000 votes to Hoover's 15,750,000. With a 472-59 margin in the Electoral College, he captured every state south and west of Pennsylvania. Roosevelt carried more counties than a presidential candidate had ever won before, including 282 that had never gone Democratic. Of the forty states in Hoover's victory coalition four years before, the President held but six."

Wallace's pro-Roosevelt campaign was also effective. For only the second time since statehood, Iowa backed a Democratic candidate for president. The day after the election, Wallace wrote to Bernard Baruch : "I am writing you today to carry out a promise which I made to you as I was leaving your office on Wednesday, March 23. At that time, you will remember that you made the statement that Iowa would never go Democratic, that the prejudice of the middle-western farmer was so deep that nothing could ever be done to shake it... I don't think you realized last spring, and I doubt if you realize now how mightily our people in this section of the country are being shaken."

Secretary of Agriculture

In late November, 1932, Raymond Moley told Wallace that Roosevelt wanted to see him in Warm Springs, Georgia. Roosevelt asked Wallace if he would join his team in Washington that were drafting new legislation for when he became president. He agreed and on 6th February, 1933, Wallace was invited to become Secretary of Agriculture. Wallace waited six days before accepting the post.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked Rexford Tugwell what post he would like. He replied that he would like to be appointed assistant secretary of agriculture under Wallace. The authors of American Dreamer: A Life of Henry A. Wallace (2001) has commented: "They presented a rather odd picture together - the dapper Columbia University professor and the tousled Iowa editor - but they made a good team. They were men of ideas and shared a vision of government that was activist and progressive. Wallace knew the practical aspects of American farming in the way a sailor knew the stars. And Tugwell knew Franklin Roosevelt."

One of Roosevelt's main advisors, Hugh S. Johnson, favoured the McNary-Haugen Farm Relief proposal that had been rejected several times by Congress. Johnson contacted Raymond Moley and told him: "It seems possible to make such contacts between farm cooperatives or a corporation to be owned by them and existing organizations for the distribution of farm products as will make the farmer a partner... in the journey of his product all the way from the farm through the processor, clear to the ultimate consumer." Johnson's ideas were passed on to the people directly involved in agricultural policy, including Wallace, Guy Tugwell and Henry Morgenthau. However, they were already committed to the alternative policy of "domestic allotment".

On 8th March 1933, Wallace and Tugwell met with Roosevelt and asked him to expand the scope of the special congressional session to include the agricultural crisis as well as the banking emergency. Roosevelt agreed to this suggestion and it was agreed to summon the nation's farm leaders to an "emergency conference" to be held in Washington. Wallace went on national radio and told the country: "Today, in this country, men are fighting to save their homes. That is not just a figure of speech. That is a brutal fact, a bitter commentary on agriculture's twelve years' struggle.... Emergency action is imperative."

On 11th March, Wallace reported: "The farm leaders were unanimous in their opinion that the agricultural emergency calls for prompt and drastic action.... The farm groups agree that farm production must be adjusted to consumption, and favor the principles of the so-called domestic allotment plan as a means of reducing production and restoring buying power." The conference also called for emergency legislation granting Wallace extraordinarily broad authority to act, including power to control production, buy up surplus commodities, regulate marketing and production, and levy excise taxes to pay for it all.

John C. Culver and John C. Hyde, the authors of American Dreamer: A Life of Henry A. Wallace (2001) have pointed out: "The sense of urgency was hardly theoretical. A true crisis was at hand. Across the Corn Belt, rebellion was being expressed in ever more violent terms. In the first two months of 1933, there were at least seventy-six instances in fifteen states of so-called penny auctions, in which mobs of farmers gathered at foreclosure sales and intimidated legitimate bidders into silence. One penny auction in Nebraska drew an astounding crowd of two thousand farmers. In Wisconsin farmers bent on stopping a farm sale were confronted by deputies armed with tear gas and machine guns. A lawyer representing the New York Life Insurance Company was dragged from the courthouse in Le Mars, Iowa, and the sheriff who tried to help him was roughed up by a mob."

The American Communist Party were active in rural areas, including Ella Reeve Bloor, who according to one historian "set up shop in hard-hit rural areas and began dispensing doughnuts and Marxist ideology". However, the main problem for Wallace was Milo Reno, the leader of the Farmers' Holiday Association. He had not been invited to Wallace's emergency farm conference and instead he led some three thousand disgruntled farmers on a march to the state capitol in Des Moines, where he issued a sweeping list of demands and vowed to mount a nationwide farm strike if they were not met.

Wallace later recalled: "To make provision for flexibility in the bill; to give the Secretary of Agriculture power to make contracts to reduce acreage with millions of individuals, and power to make marketing agreements with processors and distributors; to transfer to the Secretary, even if temporarily, the power to levy processing taxes; to express in legislation the concept of parity - all these points, and a thousand others, were unorthodox and difficult to express even by men skilled in the law." Wallace, on the advice of Felix Frankfurter, recruited Jerome Frank to draft the legislation. Other helpers included Rexford Tugwell, George N. Peek, Mordecai Ezekiel and Chester R. Davis.

Wallace walked it over to the White House and handed it to Roosevelt personally. The president in turn sent it off to Congress with a message to the nation: "I tell you frankly that it is a new and untrod path, but I tell you with equal frankness that an unprecedented condition calls for the trial of new means." An editorial in The New York Herald Tribune argued: "Seldom, if ever, has so sweeping a piece of legislation been introduced in the American Congress".

Congress asked for amendments to be added to the bill. On 13th April the Senate voted 47 to 41 in favour of incorporating "cost of production" into the bill. Wallace had always argued against this as it would effectively turn farming into a regulated public utility. Wallace claimed the "purchasing power of city dwellers was so low in 1933 that an effort to fix the price of food at a high level would result in an economic and political disaster".

On 27th April at Le Mars in Plymouth County, a mob of six hundred farmers marched on the local courthouse. A spokesman for the group asked the judge to promise that he would not sign any more foreclosure orders. Judge Charles C. Bradley said he had as much sympathy for the farmers who had lost their property, but that he did not make the laws. The men did not like this answer and dragged Bradley of his courtroom and taken to a crossroads outside of town, where his trousers were removed and he was threatened with mutilation. A noose was pulled tight around his neck, and the mob demanded that the strangling judge promise no further foreclosures. The sixty-year old Bradley bravely replied: "I will do the fair thing to all men to the best of my knowledge." Bradley was just about to be hanged when he was saved by a local newspaper editor who had just arrived in his car.

Agricultural Adjustment Act

The case made the front page of the New York Times. Governor Clyde Herring declared martial law and sent troops to the town. Milo Reno claimed that the Farmers' Holiday Association had nothing to do with the incident. His statement was widely disbelieved when the president of the Plymouth County Farmers Holiday Association was one of the 86 men arrested. Reno and his followers were heavily criticized and he lost considerable popular support. However, Wallace was now seen as a moderate and the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) was now passed by Congress.

The objective of the AAA was for a reduction in food production, which would, through a controlled shortage of food, raise the price for any given food item through supply and demand. The desired effect was that the agricultural industry would once again prosper due to the increased value and produce more income for farmers. In order to decrease food production, the AAA would pay farmers not to farm and the money would go to the landowners. The landowners were expected to share this money with the tenant farmers. While a small percentage of the landowners did share the income, the majority did not.

George N. Peek, who had been placed in charge of the AAA by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, was was adamantly opposed to the production quotas, which he saw as a form of socialism. The authors of American Dreamer: A Life of Henry A. Wallace (2001) have argued: "Crusty and dogmatic, Peek still seethed with resentment over Wallace's appointment as secretary, a position he coveted. Moreover, Peek had no use for the domestic allotment plan, which was the heart of the AAA program." To Peek the plan represented "the promotion of planned scarcity" and according to his autobiography, Why Quit Our Own? (1936), he was "steadfastly against it" from the outset.

Wallace appointed Jerome Frank as the AAA's general counsel. John C. Culver has argued: "Frank was liberal, brash, and Jewish. Peek loathed everything about him. In addition, Frank surrounded himself with idealistic left-wing lawyers... whom Peek also despised." This included Adlai Stevenson, Alger Hiss and Lee Pressman. Peek later wrote that the "place was crawling with... fanatic-like... socialists and internationalists."

Peek's main objective was to raise agricultural prices through cooperation with processors and large agribusinesses. Other members of the Agricultural Department such as Jerome Frank was primarily concerned to promote social justice for small farmers and consumers. On 15th November, 1933, Peek demanded that Wallace should fire Frank for insubordination. Wallace, who agreed more with Frank than Peek, refused.

George N. Peek became completely disillusioned with the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA). He wrote in his autobiography, Why Quit Our Own? (1936): "There is no use mincing words... The AAA became a means of buying the farmer's birthright as a preliminary to breaking down the whole individualistic system of the country." However, it was clear that President Franklin D. Roosevelt supported Wallace over Peek.

In December 1933, Wallace accompanied Roosevelt on a visit to Warm Springs. Peek seized the opportunity to announce a half-million-dollar plan to subsidize the sale of butter in Europe. Peek's action was intended as a declaration of independence, but Rexford Tugwell, acting secretary in Wallace's absence, took it as insubordination. Tugwell wrote in his autobiography that "it was becoming obvious that if we did not get rid of George Peek, he would get rid of us." He said this to Roosevelt and it was agreed that Peek should be moved from the AAA.

A few days later, Wallace made a speech where he said the dairy program had been a failure. Although he did not make reference to George N. Peek, it was clearly a comment of his policy at the AAA. John Franklin Carter commented: "That is the coolest political murder that has been committed since Roosevelt came into office." Peek resigned from the AAA on 11th December, 1933. The same day, President Roosevelt named Peek his Special Advisor on Foreign Trade.

Under the terms of the Agricultural Adjustment Act farmers were paid money not to grow crops and not to produce dairy produce such as milk and butter. The money to pay the farmers for cutting back production of about 30% was raised by a tax on companies that bought the farm products and processed them into food and clothing.

Wallace controversially agreed that hog farmers should be allowed to slaughter pigs weighing less than one hundred pounds instead of allowing them to reach their usual market weight of two hundred pounds. It was argued that pigs would be reduced by five or six million, prices would rise, and the edible portions of the pigs could be used to feed the hungry. William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963), has pointed out: "Wallace reluctantly agreed to a proposal of farm leaders to forestall a glut in the hog market by slaughtering over six million little pigs and more than two hundred thousand sows due to farrow. While one million pounds of salt pork was salvaged for relief families, nine-tenths of the yield was inedible, and most of it had to be thrown away. The country was horrified by the mass matricide and infanticide. When the piglets overran the stockyards, and scampered squealing through the streets of Chicago and Omaha, the nation rallied to the side of the victims of oppression, seeking to flee their dreadful fate."

Newspapers denounced Wallace's plan as "pig infanticide". Wallace was surprised by the criticism as it is "just as inhumane to kill a big hog as a little one". Wallace added: "To hear them talk, you would have thought that pigs are raised for pets. Nor would they realize that the slaughter of little pigs might make more tolerable the lives of a good many human beings being dependent on hog prices." Some one million pounds of pork, and pork by-products, such as lard and soap, was distributed to poor. Wallace pointed out: "Not many people realized how radical it was - this idea of having the Government buy from those who had too much, in order to give to those who had too little."

Wallace was popular with farmers. As Frances Perkins pointed out: "Wallace was very able, clear-thinking, high-minded, a man of patriotism and nobility of character. Her had a following among farmers. He was one of the few people with an agricultural background who had begun to make himself comprehensible to the industrial working people of the country." The journalist, John Franklin Carter, commented: "He is as earthy as the black loam of the corn belt, as gaunt and grim as a pioneer. With all of that, he has an insatiable curiosity and one of the keenest minds in Washington, well-disciplined and subtle, with interests and accomplishments which range from agrarian genetics to astronomy. If the young men and women of this country look to the west for a liberal candidate for the Presidency - as they may in 1940 - they will not be able to overlook Henry Wallace."

Sherwood Anderson was another who was impressed with Wallace: "He has an inner rather than an outward smile... perhaps just at bottom sense of the place in life of the civilized man... no swank... something that gives us confidence." However, others accused him of faddism and pointed out that on one occasion lived on corn meal and milk after learning that this had been the food of Julius Caesar and his army in Gaul.

Wallace and Rexford Tugwell were seen as the leading liberals in Roosevelt's government. Tugwell defended his liberal views by arguing: "Liberals would like to rebuild the station while the trains are running; radicals prefer to blow up the station and forgo service until the new structure is built." Wallace and Tugwell had a strong following amongst liberals in the Democratic Party. John C. Hyde commented "the reformers... saw in Wallace a reflection of themselves: young, idealistic, open-minded, comfortable with intellectual give-and-take, and repulsed by the excesses of capitalism."

In the 1930s it was estimated that 45 per cent of the cotton tenants were "sharecroppers" who lived in shacks provided by the landlord. They were forced to buy food at inflated prices in landlord-owned stores and received a portion of the crop in lieu of wages. Norman Thomas, the leader of the Socialist Party of America, denounced this system as "involuntary servitude" and a form of slavery. Thomas told Henry Wallace that the AAA cotton program was not helping the plight of most sharecroppers. The contracts required cotton plantation owners to share government benefits with their tenants, but the provision was being poorly enforced.

In June 1934 the Southern Tenant Farmers' Union (STFU) was established in response to allegations that an absentee landlord had evicted some forty tenant families in Arkansas. Led by socialists, the STFU promoted the idea that blacks and whites could work efficiently together. According to William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963): "It was in Arkansas that croppers and farm laborers, driven to rebellion by the hard handed tactics of the landlords and the AAA committees, established the Southern Tenant Farmers' Union in July, 1934. Under socialist leadership, the farmers, Negro and white-some of the whites had been Klansmen-organized in the region around Tyronza."

The landlords struck back with a campaign of terrorism." The journalist, Dorothy Detzer, argued: "Riding bosses hunted down union organizers like runaway slaves; union members were flogged, jailed, shot-some were murdered." Norman Thomas told a nationwide radio audience: "It will end either in the establishment of complete slavish submission to the vilest exploitation in America or in bloodshed, or in both."

Two of Wallace's junior members of his department, Jerome Frank and Alger Hiss, decided to draw up legislation that would protect sharecroppers from their landlords. They were aware that Chester R. Davis, the head of the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), did not support this move. They therefore persuaded Victor Christgau, his second in command to send out details of the change in the name of Wallace. Davis was furious when he discovered what had happened. He later recalled: "The new interpretations completely reversed the basis on which cotton contracts had been administered through the first year. If the contract had been so construed, and if the Department of Agriculture had enforced it, Henry Wallace would have been forced out of the Cabinet within a month. The effects would have been revolutionary."

Davis insisted that Frank and Hiss should be dismissed. Wallace was unable to protect them: "I had no doubt that Frank and Hiss were animated by the highest motives, but their lack of agricultural background exposed them to the danger of going to absurd lengths... I was convinced that from a legal point of view they had nothing to stand on and that they allowed their social preconceptions to lead them to something which was not only indefensible from a practical, agricultural point of view, but also bad law."

Chester R. Davis told Jerome Frank: "I've had a chance to watch you and I think you are an outright revolutionary, whether you realize it or not". Wallace wrote in his diary: "I indicated that I believed Frank and Hiss had been loyal to me at all times, but it was necessary to clear up an administrative situation and that I agreed with Davis". According to Sidney Baldwin, the author of Poverty and Politics: The Rise and Decline of the Farm Security Administration (1968), Wallace greeted Frank with tears in his eyes: "Jerome, you've been the best fighter I've had for my ideas, but I've had to fire you... The farm people are just too strong."

Rexford Tugwell was unhappy with Wallace's decision and thought he should have sacked Chester R. Davis instead: "He (Wallace) gave up his policy. It was more a failure of leadership than anything else. It was letting himself be pushed around by what I thought were pretty sinister forces." Raymond Gram Swing, wrote in the Nation Magazine that Wallace had shown himself unwilling to stand up to big producers and agribusiness and seize "economic power from the interests in agriculture who hold it."

Farmers in the Mid-West faced another serious problem. During the First World War, farmers grew wheat on land normally used for grazing animals. This intensive farming destroyed the protective cover of vegetation and the hot dry summers began to turn the soil into dust. High winds in 1934 turned an area of some 50 million acres into a giant dust bowl. Wallace wrote: "To see rich land eaten away by erosion, to stand by as continual cultivation on sloping fields wears away the best soil, is enough to make a good farmer sick at heart."

Milo Reno, the head of Farmers' Holiday Association and Floyd Olson, the Governor of Minnesota, insisted on compulsory production control and price-fixing, with a guaranteed cost of production. Wallace argued this was against the idea as it would mean licensing every ploughed field in the country. Reno responded by calling a strike. According to William E. Leuchtenburg: "Strikers dumped kerosene in cream, broke churns, and dynamited dairies and cheese factories."

Despite these problems, Wallace's farm program worked out fairly well. Between 1933 and 1936 gross farm income rose 50 per cent, crop prices climbed, and rural debts were reduced sharply. Government payments to farmers benefited merchants and mail order houses. Sewell Avery, the head of Montgomery Ward, admitted that the AAA had been the single greatest reason for the company's growth in revenues.

The Agricultural Adjustment Act had a powerful enemy in the food processors that paid the tax that generated revenue for the farm subsidies. Wallace argued that the tax was actually an excise tax eventually passed along to consumers. In other words, "the processing tax is the farmer's tariff". He also suggested the tax was actually an excise tax was a matter of fundamental fairness.

William M. Butler, a wealthy textile manufacturer, and a leading figure in the Republican Party, took the case to the Supreme Court. Justice Owen J. Roberts, declared in a 7,000-word opinion, that agriculture was "a purely local activity" and should not be subjected to regulation by the federal government. If the AAA were allowed to stand, Roberts added, the rights of individual states would be "obliterated, and the United States converted into a central government exercising controlled police power in every state of the Union."

Justice Harlan Fiske Stone disagreed with the views of Roberts. "Courts are not the only agency of government that must be assumed to have the capacity to govern." The wisest course, he said, would be for the Court to admit that the Constitution "may mean what it says: that the power to tax and spend includes the power to relieve a nationwide economic maladjustment by conditional gifts of money. However, in January 1936 the Supreme Court ruled (6-3) that the regulation of agriculture was a state power and therefore the AAA was unconstitutional.

Wallace's anger turned to outrage when the Supreme Court ordered $200 million of impounded processing taxes be returned to the manufacturings. Wallace retorted: "This is probably the greatest legalized steal in American history... I do not question the legality of this action, but I certainly do question the justice of it." Wallace immediately set out to draw up legislation that would be acceptable to the Supreme Court.

On February 27 1936, Congress enacted the Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed it into law two days later. It had taken only 56 days from the death of the New Deal farm program to its resurrection. Howard Ross Tolley was named to administer the new program, replacing Chester R. Davis, who had created problems for Wallace in the past. In 1938, another AAA was passed without the processing tax. It was financed out of general taxation and was therefore acceptable to the Supreme Court.

Wallace played an important role in the 1936 Presidential Election. The Des Moines Register reported: "Of all the members of the New Deal cabinet, Wallace - originally a nonpartisan selection - now bears the most political responsibility and has been shoved forward as the No. 2 in the campaign." During the election campaign, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was attacked for not keeping his promise to balance the budget. The National Labour Relations Act was unpopular with businessmen who felt that it favoured the trade unions. Some went as far as accusing Roosevelt of being a communist. However, the New Deal was extremely popular with the electorate and Roosevelt easily defeated the Republican Party candidate, Alfred M. Landon, by 27,751,612 votes to 16,681,913.

Wallace continued to argue for government intervention. On 1st April, 1937, Wallace gave a lecture at the University of North Carolina entitled, Technology, Corporations and the General Welfare, where he argued the country could no longer afford the luxury of laissez-faire capitalism: "The impact of modern technology through the corporate form of organization, and the control by corporations over price and production, are such as to make the problem of the one-third of the population at the bottom of the heap practically hopeless unless the government steps in definitely and powerfully on behalf of the general welfare.

Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau argued that it was now time for the government to stand aside - "to strip off the bandages, throw away the crutches" - and allow business to restore the country to economic vigor. Morgenthau also believed it was time for the government to start cutting spending. Wallace disagreed with this view and suggested it would be disastrous to try and balance the budget during a recession. He was supported in this by Harry Hopkins, Marriner Eccles and Harold Ickes and Roosevelt's economic policies continued.

Henry Wallace, unlike progressives such as George Norris, William Borah and Robert LaFollette Jr., was an internationalist. Wallace's thinking had been deeply influenced by the economist Thorstein Veblen, who had argued that states such as Germany and Japan, which had developed a modern industrial economy without parallel democratic institutions, were bound to express their national identity in authoritarianism.

Nazi Germany

Wallace was an early opponent of Adolf Hitler. In an article written 21st April 1938, Wallace warned that the Nazi dictatorship "is teaching the German boys and girls to believe that their race and their nation are superior to all others, and by implication that nation and that race have a right to dominate all others." He added that "no race has a monopoly on desirable genes and there are geniuses in every race." He then went on to describe his relationship with George Washington Carver, the great black scientist, who Wallace believed was a genius. Wallace argued that 100,000 babies taken from "poor white" families and raised in wealthy circumstances would turn out differently from 100,000 well-to-do babies, or 100,000 German babies, or 100,000 Jewish babies.

Wallace was a strong supporter of the use of science to support democracy. In one speech he argued: "The cause of liberty and the cause of true science must always be one and the same. For science cannot flourish except in an atmosphere of freedom, and freedom cannot survive unless there is an honest facing of facts... Democracy - and that term includes free science - must apply itself to meeting the material need of men for work, for income, for goods, for health, for security, and to meeting the spiritual need for dignity, for knowledge, for self-expression, for adventure and for reverence. And it must succeed. The danger that it will be overthrown in favor of some other system is in direct proportion to its failure to meet those needs... In the long run, democracy or any other political system will be measured by its deeds, not its words."

On 29th September 1938, Neville Chamberlain and Edouard Daladier met Adolf Hitler in Munich. Desperate to avoid war, and anxious to avoid an alliance with Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Union, Chamberlain and Daladier agreed that Germany could have the Sudetenland. In return, Hitler promised not to make any further territorial demands in Europe. Wallace urged President Franklin D. Roosevelt to take action against Hitler. Roosevelt eventually sent a letter of protest to Hitler. Wallace told Roosevelt: "There is a danger that people in foreign lands and even some in this country will look on your effort as being in the same category as delivering a sermon to a mad dog."

Vice-President

In 1940 Wallace, Harry Hopkins, Harold Ickes and Thomas Corcoran called on Roosevelt to seek a third term. Roosevelt would therefore became the first person to break the unwritten rule that presidents do not stand for more than two-terms in succession. John Nance Garner, the vice-president openly declared his opposition to a third term for Roosevelt. Garner suggested that the Democratic Party candidate should be Jesse H. Jones, the conservative and powerful head of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation.

Roosevelt accepted the nomination and selected Wallace as his running-mate. He told a friend the reason for his decision was that Wallace was a genuine New Dealer, an internationalist, in good health with plenty of energy and a loyalist on the Supreme Court and other controversial issues. James Farley , who had become disillusioned with the New Deal, argued against the decision: "Henry Wallace won't add a bit of strength to the ticket... He won't bring you the support you may expect in the farm belt and he will lose votes for you in the East... He has always been most cordial and cooperative with me, but I think you must know that the people look on him as a wild-eyed fellow." Harold Ickes also warned Roosevelt not to select Wallace and instead suggested Robert Maynard Hutchins.

At the Democratic Convention in Chicago Roosevelt was challenged by Garner and Farley for the nomination. The delegates gave Roosevelt 946 votes, Garner 61 and Farley 52. Wallace was challenged by John Hollis Bankhead of Alabama and despite the backroom efforts of James F. Byrnes and Paul McNutt, he won with 626 votes to 329. However, the decision was greeted with boos. The veteran journalist, Arthur Krock, wrote: "Mr. Wallace deserved a better fate than the boos that greeted the mention of his name and the distaste of the delegates over nominating him. He is able, thoughtful, honorable - the best of the New Deal type."

At Philadelphia in 1940 the Republican Party chose Wendell Willkie as their presidential candidate. His running-mate, Charles L. McNary, was a well-know isolationist. During the campaign Paul Block, publisher of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, managed to get hold of some letters written by Wallace to Nicholas Roerich in 1933-34. The content of the letters suggested that Wallace held left-wing views and unconventional opinions on religion. Harry Hopkins contacted Block and told him if he published the letters they would reveal that Willkie was having an affair with Irita Van Doren, the literary editor of the New York Herald Tribune. As a result, Block did not publish the letters.

During the campaign Willkie attacked the New Deal as being inefficient and wasteful. However, he refused to take advantage of Roosevelt's decision to prepare for possible war with Nazi Germany. In one speech Wallace had argued: "It is strength only that Hitler respects. By preparedness we can win and hold our peace." Willkie agreed with Roosevelt's decision to spend $5.2 billion to build 7 battleships and 201 other ships of war. At the election Roosevelt beat Willkie by 27,244,160 (54.7%) votes to 22,305,198 (44.8%). Norman Thomas, the candidate of the American Socialist Party received only 116,599 votes.

Wallace argued forcefully that the United States should prepare for war: "Complete preparedness is more than tanks and guns and aircraft. It is more than well-trained officers and adequate reserves. To repel the sneaking enemy that burrows from within, the all-important preparedness is moral preparedness and social preparedness. The best preparedness of all is every able-bodied person working whole-heartedly for our mutual security and defense in the belief that he or she is needed. You are needed. You are all needed to see that every child is properly fed and clothed, to see that every family has an opportunity to protect itself from hunger, cold and lack of shelter."

Second World War

After the United States joined the Second World War, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Wallace as head of the powerful Board of Economic Warfare. It has been claimed that in this post "Wallace had become the most powerful vice president in the nation's history. No vice president had ever wielded such administrative authority, much less a policy voice of consequence." Wallace later commented that Roosevelt "used me in a way which made the office for a time a very great office".

The publisher, Cass Canfield, worked under Wallace and in his autobiography, Up, Down and Around (1972), commented: "The Board of Economic Warfare was a vital, somewhat reckless organization filled with bright people. Quite a few of them came from Henry Wallace's Department of Agriculture, which probably had more talent in it than any agency in Washington. Vice President Wallace, Chairman of the BEW, was not primarily involved in its operations - rather with broad policy. It was Milo Perkins who was the efficient operating head."

Wallace argued in Atlantic Monthly that the war should be about developing a fairer world: "The overthrow of Hitler is only half the battle; we must build a world in which our human and material resources are used to the utmost if we are to win complete victory. This principle should be fundamental as the world moves to reorganize its affairs. Ways must be found by which the potential abundance of the world can be translated into real wealth and a higher standard of living. Certain minimum standards of food, clothing and shelter ought to be established, and arrangements ought to be made to guarantee that no one should fill below those standards."

On 8th May, 1942, Wallace made a speech that attacked the ideas of Henry Luce, the magazine publisher, who had advocated entry into the Second World War because it would enable the United States to become the "world's dominant power" and that it could be the "American Century". Wallace argued: "I say that the century on which we are entering - the century which will come out of this war - can be and must be the century of the common man. Everywhere the common man must learn to build his own industries with his own hands in a practical fashion. Everywhere the common man must learn to increase his productivity so that he and his children can eventually pay to the world community all that they have received. No nation will have the God-given right to exploit other nations. Older nations will have the privilege to help younger nations get started on the path to industrialization, but there must be neither military nor economic imperialism. The methods of the nineteenth century will not work in the people's century which is now about to begin."

On 8th March, 1943, Wallace made a speech where he stressed the need to create a better post-war world: "Those who think most about unity, whether it he the unity of a nation or of the entire world, preach the sacred obligation of duty. There is a seeming conflict between freedom and duty, and it takes the spirit of democracy to resolve it. Only through religion and education can the freedom-loving individual realize that his greatest private pleasure comes from serving the highest unity, the general welfare of all. This truth, the essence of democracy, must capture the hearts of men over the entire world if human civilization is not to be torn to pieces in a series of wars and revolutions far more terrible than anything that has yet been endured. Democracy is the hope of civilization.... We shall decide sometime in 1943 or 1944 whether to plant the seeds for World War III. That war will be certain if we allow Prussia to rearm either materially or psychologically. That war will be probable in case we double-cross Russia. That war will be probable if we fail to demonstrate that we can furnish full employment after this war comes to an end and if fascist interests motivated largely by anti-Russian bias get control of our government. Unless the Western democracies and Russia come to a satisfactory understanding before the war ends, I very much fear that World War III will be inevitable."

Walter Lippmann, the most important newspaper columnist of the era, argued that Wallace's idealism was unrealistic and unattainable: "National ideals should express the serious purposes of the nation and the vice of the pacifist ideal is that it conceals the true end of foreign policy. The true end is to provide for the security of the nation in peace and in war."

Wallace was strongly opposed to colonialism. This caused conflict with Winston Churchill, the British prime minister. At a meeting in May, 1943, he clashed with Churchill about his views on the post-war world: "He made it more clear than he had at the luncheon on Saturday that he expected England and the United States to run the world and he expected the staff organizations which had been set up for winning the war to continue when the peace came, that these staff organizations would by mutual understanding really run the world even though there was a supreme council and three regional councils... I said bluntly that I thought the notion of Anglo-Saxon superiority, inherent in Churchill's approach, would be offensive to many of the nations of the world as well as to a number of people in the United States. Churchill had had quite a bit of whiskey, which, however, did not affect the clarity of his thinking process but did perhaps increase his frankness. He said why be apologetic about Anglo-Saxon superiority, that we were superior, that we had the common heritage which had been worked out over the centuries in England and had been perfected by our constitution. He himself was half American, he felt that he was called on as a result to serve the function of uniting the two great Anglo-Saxon civilizations in order to confer the benefit of freedom on the rest of the world."

Wallace grew increasingly worried about the post-war world. President Franklin D. Roosevelt told Wallace that it was "highly essential that the United States and Russia understand each other better". Wallace responded that "the conservatives in both England and in the United States are working together and that their objective will be to create a situation which will eventually lead to war." Wallace later recalled that Roosevelt agreed with him on this point.

On 9th April, 1944, Wallace published an article in the New York Times warning of fascism in America: "The American Fascists are most easily recognized by their deliberate perversion of truth and fact.... They cultivate hate and distrust of both Britain and Russia. They claim to be super-patriots, but they would destroy every liberty guaranteed by the Constitution. They demand free enterprise, but are the spokesmen for monopoly and vested interest. Their final objective, toward which all their deceit is directed, is to capture political power, so that using the power of the State and the power of the market simultaneously they may keep the common man in eternal subjection."

Wallace's left-wing views made him increasingly unpopular in the Democratic Party and Roosevelt came under pressure to drop him as his vice-president in 1944. Jack L. Bell argued: "The Vice President knows from experience that if President Roosevelt is a candidate he will pick his own running-mate. His friends say that if he is able to demonstrate that he speaks for the liberals and labor it will be difficult for Mr. Roosevelt to cast him aside."

Even liberals in Roosevelt's administration such as Harry Hopkins argued that Wallace was too left-wing and should be dropped as vice-president for the 1944 Presidential Election. A public opinion poll showed that Wallace was a popular figure and a survey to discover who Roosevelt's running-mate should be, suggested that he should be selected: The results were as follows: Wallace (46%), Cordell Hull (21%), James Farley (13%), Sam Rayburn (12%), James F. Byrnes (5%) and Harry F. Byrd (3%).

Walter Lippmann argued against Wallace being nominated as he considered him to be emotionally unsuited to be president: "We can't take the risk. This man may go crazy. we know that Roosevelt is not immortal." Robert Hannegan, the chairman of the Democratic National Committee, was totally opposed to Wallace and suggested that he should select Harry S. Truman instead. Roosevelt told Wallace he had a problem because some people were telling him that they thought he was "a Communist - or worse".

At the Democratic National Convention in 1944 Wallace upset most of the party bosses by making a passionate defence of liberalism. "The future belongs to those who go down the line unswervingly for the liberal principles of both political democracy and economic democracy regardless of race, color or religion. In a political, educational and economic sense there must be no inferior races. The poll tax must go. Equal educational opportunities must come. The future must bring equal wages for equal work regardless of sex or race. Roosevelt stands for all this. That is why certain people hate him so. That also is one of the outstanding reasons why Roosevelt will be elected for a fourth time."

In McCook, Nebraska, a dying George Norris heard the speech and immediately sent him a letter: "I do not suppose it would be considered a proper speech for that occasion by the politicians. If you had been trying to appease somebody you made a mistake, but you were talking straight into the faces of your enemies who were trying to defeat you, and no matter what they may think or what effect it may have on them, the effect on the country and all those who will read that speech is that it was one of the most courageous exhibitions ever seen at a political convention in this country."

Claude Pepper organized a parade in favour of Wallace. Jennet Conant, the author of The Irregulars: Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington (2008), has argued: "Senator Claude Pepper, who was with the Florida delegation, thought that Wallace parade had pulled it off. From what he could see, standing on his chair and looking down at the forest of state standards raised in the air, it appeared that 'if a vote was taken that evening, Wallace would be nominated'. The Wallace demonstrators looked like they were about to riot. Hannegan, realizing that emotions had become too hot, hastily yelled at the party chairman to adjourn the night session. Pepper tried to reach the platform, to appeal to the floor not to adjourn. With a bang of his gavel, it was over. The crowd groaned in protest, but the police were already ushering them toward the exists."

The speech put President Franklin D. Roosevelt in a difficult position and he now refused to come out openly for Wallace. The vote at the end of the first ballot was 429 to Wallace and 319 for Harry S. Truman. Conservatives in the party now decided to take action. Other candidates, Herbert O'Conor and John Hollis Bankhead, withdrew in favour of Truman. Robert Hannegan now approached others to change their vote. Hannegan later said, he would like his tombstone to be inscribed with the words: "Here lies the man who stopped Henry Wallace from becoming President of the United States." At the next ballot Truman won 1,031 votes against Wallace's 105. It later emerged that Bernard Baruch had offered Roosevelt a million dollars if he ran on a ticket without Wallace.

In the 1944 Presidential Election Roosevelt and Truman comfortable beat Thomas E. Dewey and John W. Bricker by 25,612,916 votes (53.4%) to 22,017,929 votes (45.9%). Wallace loyally supported Roosevelt during the election and he was rewarded by being given the post of Secretary of Commerce. He retained the post after Roosevelt died on on 7th May, 1945. Although most of the liberals in the administration lost their posts.

Wallace became highly critically of the foreign policy of Harry S. Truman and James F. Byrnes. In his diary, he wrote: "It is obvious to me that the cornerstone of the peace of the future consists in strengthening our ties of friendship with Russia. It is also obvious that the attitude of Truman, Byrnes, and both the war and navy departments is not moving in this direction. Their attitude will make for war eventually."

The Cold War

On 12th September, 1946 Wallace made a speech about the atom bomb: "During the past year or so, the significance of peace has been increased immeasurably by the atom bomb, guided missiles, and airplanes which soon will travel as fast as sound. Make no mistake about it - another war would hurt the United States many times as much as the last war... He who trusts in the atom bomb will sooner or later perish by the atom bomb - or something worse. I say this as one who steadfastly backed preparedness throughout the thirties. We have no use for namby-pamby pacifism. But we must realize that modern inventions have now made peace the most enticing thing in the world - and we should be willing to pay a just price for peace."

Wallace went on to argue that the government needed to tackle racism: "The price of peace - for us and for every nation in the world - is the price of giving up prejudice, hatred, fear and ignorance.... Hatred breeds hatred. The doctrine of racial superiority produces a desire to get even on the part of its victims. If we are to work for peace in the rest of the world, we here in the United States must eliminate racism from our unions, our business organizations, our educational institutions, and our employment practices. Merit alone must be the measure of men."

James F. Byrnes was furious about the speech and he sent a message to President Harry S. Truman: If it is not possible for you, for any reason, to keep Mr. Wallace, as a member of your cabinet, from speaking on foreign affairs, it would be a grave mistake from every point of view for me to continue in office, even temporarily." Truman wanted to keep Byrnes and after complaints from James Forrestal, Secretary of Defence, he forced Wallace to resign on 20th September, 1946.

Wallace received several letters of support. Albert Einstein wrote: "Your courageous intervention deserves the gratitude of all of us who observe the present attitude of our government with grave concern. Hellen Keller also praised Wallace: "Rejoicing I watch you faring forth on a renewed pilgrimage looking not downwards to ignoble acquiescence or around at fugitive expediency, but upward to mind-quickening statecraft and life-saving peace for all lands." Thomas Mann sent a telegram: "Like millions of good Americans we not only share your views on foreign policy but are deeply impressed with your courage and consistency in defending them."

After he left government Wallace returned to journalism. Michael Straight, the publisher of The New Republic, appointed Wallace as editor of the magazine on a salary of $15,000 a year. Money was not an issue for Wallace as Pioneer Hi-Bred earned more than $150,000 in dividends in 1946. Wallace wrote that: "As editor of The New Republic I shall do everything I can to rouse the American people, the British people, the French people, the Russian people and in fact the liberally-minded people of the whole world, to the need of stopping this dangerous armament race."

Progressive Citizens of America

Wallace formed the Progressive Citizens of America (PCA). Members included Rexford Tugwell, Paul Robeson, W.E.B. Du Bois, Arthur Miller, Dashiell Hammett, Hellen Keller, Jo Davidson, Thomas Mann, Aaron Copland, Claude Pepper, Eugene O'Neill, Glen H. Taylor, John Abt, Edna Ferber, Thornton Wilder, Carl Van Doren, Anne Braden, Carl Braden, Fredric March and Gene Kelly. A group of conservatives, including Henry Luce, Clare Booth Luce, Adolf Berle, Lawrence Spivak and Hans von Kaltenborn, sent a cable to Ernest Bevin, the British foreign secretary, that the PCA were only "a small minority of Communists, fellow-travelers and what we call here totalitarian liberals." Winston Churchill agreed and described Wallace and his followers as "crypto-Communists".

Wallace also led the attacks against the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). On 19th May, 1947, he argued: "We burned an innocent woman on charge of witchcraft. We earned the scorn of the world for lynching negroes. We hounded labor leaders and socialists at the turn of the century. We drove 100,000 innocent men and women from their homes in California because they were of Japanese ancestry.... We branded ourselves forever in the eyes of the world for the murder by the state of two humble and glorious immigrants - Sacco and Vanzetti.... These acts today fill us with burning shame. Now other men seek to fasten new shame on America.... I mean the group of bigots first known as the Dies Committee, then the Rankin Committee, now the Thomas Committee - three names for fascists the world over to roll on their tongues with pride."

Americans for Democratic Action (ADA), that included Arthur Schlesinger, Eleanor Roosevelt, Walter Reuther, Hubert Humphrey, Asa Philip Randolph, John Kenneth Galbraith,Walter F. White,Louise Bowen, Chester Bowles, Louis Carlo Fraina, Stewart Alsop, Reinhold Niebuhr, George Counts, David Dubinsky and Joseph P. Lash, refused to support Wallace and the Progressive Citizens of America (PCA) because they objected to the fact that it allowed members of the American Communist Party (ACP) to join: "We reject any association with Communism or sympathizers with communism in the United States as completely as we reject any association with Fascists or their sympathizers."

In January 1948, The New Republic reached a circulation of a record 100,000. Michael Straight was unhappy with Wallace's involvement of the Progressive Citizens of America, his collaboration with the ACP. Straight was a supporter of the Marshall Plan and the anti-communism policies of President Harry S. Truman and therefore decided to sack Wallace as editor.

1948 Presidential Election

Wallace decided to stand in the 1948 Presidential Election. His running-mate was Glen H. Taylor, the left-wing senator for Idaho. Wallace's chances were badly damaged when William Z. Foster, head of the American Communist Party, announced he would be supporting Wallace in the election. The New York Post reported: "Who asked Henry Wallace to run? The answer is in the record. The Communist Party through William Z. Foster and Eugene Dennis were the first... The record is clear. The call to Wallace came from the Communist Party and the only progressive organization admitting Communists to its membership."