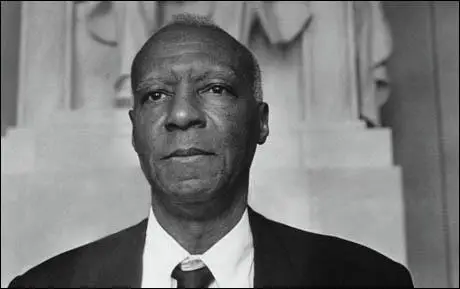

Asa Philip Randolph

Asa Philip Randolph was born in Crescent City, Florida, on 15th April, 1889. The son of a Methodist minister, he was educated locally before moving to New York City where he studied economics and philosophy at the City College.

While in New York he worked as an elevator operator, a porter and a waiter. In 1917 Randolph founded a magazine, The Messenger (later the Black Worker), which campaigned for black civil rights. During the First World War he was arrested for breaking the Espionage Act. It was claimed that Randolph and his co-editor, Chandler Owen was guilty of treason after opposing African Americans joining the army.

After the war Randolph lectured at the Rand School of Social Science. A member of the Socialist Party, Randolph made several unsuccessful attempts to be elected to political office in New York. He was was involved in organizing black workers in laundries, clothes factories and cinemas and in 1929 became president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP). Over the next few years he built it into the first successful black trade union.

The BSCP were members of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) but in protest against its failure to fight discrimination in its ranks, Randolph took his union into the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO).

Disturbed by the growing power of Adolf Hitler, in 1940 he helped establish the Union for Democratic Action, an organisation that called for American assistance to defeat fascism. Other members included Reinhold Niebuhr, George S. Counts, Louise Bowen and Louis Fraina.

After threatening to organize a March on Washington in June, 1941, Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 on 25th June, 1941, barring discrimination in defence industries and federal bureaus (the Fair Employment Act).

After the Second World War Randolph led a campaign in favour of racial equality in the military. This resulted in Harry S. Truman issuing executive order 9981 on 26th July, 1948, banning segregation in the armed forces.

When the AFL merged with the CIO, Randolph became vice president of the new organisation. He also became president of the Negro American Labor Council (1960-66).

In 1963 Randolph began involved in what became known as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. It was a great success and estimates on the size of the crowd varied from between 250,000 to 400,000. Speakers along with Randolph included Martin Luther King (SCLC), Floyd McKissick (CORE), John Lewis (SNCC), Roy Wilkins (NAACP), Witney Young (National Urban League) and Walter Reuther (AFL-CIO). King was the final speaker and made his famous I Have a Dream speech.

In his final years Randolph worked closely with Bayard Rustin in the AFL-CIO funded, Philip Randolph Institute, that was established in 1966.

Philip Randolph died in New York on 16th May, 1979.

Primary Sources

(1) Philip Randolph, The Messenger (July, 1918)

At a recent convention of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), a member of the Administration's Department of Intelligence was present. When Mr. Julian Carter of Harrisburg was complaining of the racial prejudice which American white troops had carried into France, the administration representative rose and warned the audience that the Negroes were under suspicion of having been affected by German propaganda.

In keeping with the ultra-patriotism of the oldline type of Negro leaders the NAACP failed to grasp its opportunity. It might have informed the Administration representatives that the discontent among Negroes was not produced by propaganda, nor can it be removed by propaganda. The causes are deep and dark - though obvious to all who care to use their mental eyes. Peonage, disfranchisement, Jim-Crowism, segregation, rank civil discrimination, injustice of legislatures, courts and administrators - these are the propaganda of discontent among Negroes.

The only legitimate connection between this unrest and Germanism is the extensive government advertisement that we are fighting "to make the world safe for democracy", to carry democracy to Germany; that we are conscripting the Negro into the military and industrial establishments to achieve this end for white democracy four thousand miles away, while the Negro at home, through bearing the burden in every way, is denied economic, political, educational and civil democracy.

(2) Philip Randolph, The Messenger (July, 1919)

The IWW is the only labor organization in the United States which draws no race or color line. There is another reason why Negroes should join the IWW. The Negro must engage in direct action. He is forced to do this by the Government. When the whites speak of direct action, they are told to use their political power. But with the Negro it is different. He has no political power. Therefore the only recourse the Negro has is industrial action, and since he must combine with those forces which draw no line against him, it is simply logical for him to draw his lot with the Industrial Workers of the World.

(3) George Schuyler, wrote about his time working for The Messenger in his autobiography, Black and Conservative.

Philip Randolph was one of the finest, most engaging men I had ever met. Undemanding and easy to get along with, leisurely and undisturbed, remaining affable under all circumstance, whether the rent was due and he did not have it, or whether an expected donation failed to materialize, or whether the long-suffering printer in Brooklyn was demanding money. He had a keen sense of humor and laughed easily, even in adversity.

(4) Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen , co-editors of the The Messenger, were both charged with breaking the Espionage Act in August, 1918. Randolph later wrote about his trial.

The judge was astonished when he saw us and read what we had written in the Messenger. Chandler and I were twenty-nine at the time, but we looked much younger. The judge said, why, we were nothing but boys. He couldn't believe we were old enough, or, being black, smart enough, to write that red-hot stuff in the Messenger. There was no doubt, he said, that the the white socialists were using us, that they had written the stuff for us.

He turned to us: "You really wrote this magazine? We assured him that we had. "What do you know about socialism? he said. We told him we were students of Marx and fervent believers in the socialization of social property. "Don't you know," he said, "that you are opposing your own government and that you are subject to imprisonment for treason?" We told him we believed in the principle of human justice and that our right to express our conscience was above the law.

(5) Philip Randolph met Marcus Garvey in 1916 while making a speech on behalf of the Socialist Party. He later recalled his impression of Garvey as a political leader.

I was on a soapbox speaking on socialism, when someone pulled my coat and said, "There's a young man here from Jamaica. I said, "What does he want to talk about?" He said, "He wants to talk about a movement to develop a back-to-Africa sentiment in America."

Garvey got up on the platform, and you could hear him from 135th to 125th Street. He had a tremendous voice. When he finished speaking he sat near the platform with a sheaf of paper on which he was constantly writing, and he had stamps and envelopes, ready to send out his propaganda. I could tell from watching him even then that he was one of the greatest propagandists of his time.

(6) Claude McKay wrote about Philip Randolph in Harlem, Negro Metropolis (1936)

More than any other Negro leader, he has a comprehensive understanding of the vast conquests of modern industry and the grand movement of labour to keep abreast of it. And he is aware that the Negro group is in a special position and has a special force. His outlook remains unblurred by passion and prejudice. He takes a long, balanced view of men and affairs. He could not be tagged with radical, chauvinist, nationalist, or reactionary labels, or with any other slanderous names such as the Communists and the other labor henchmen attach to those colored people who oppose their unscrupulous exploitation of Negro organizations in the interest of Soviet Russia. He believes that the mainspring of the Negro group lies within itself.

(7) Ralph Bunche, on a speech by Philip Randolph at a meeting of the Labor Non-Partisan League in April, 1940.

Randolph's speech cautioned the Negro that it would be foolish for him to tie up his own interests with the foreign policy of the Soviet Union or any other nation of the world. Nor would the Negro be sensible in hoping that through tying himself to any American organization, political or labor, he would find a ready solution for the problems. He cautioned the Congress against too close a relationship with any organization, mentioning the major parties, the Communist Party, the Socialist Party (of which he is a member) and the CIO. He expressed the view that the Negro Congress should remain independent and non-partisan, and that it should be built up by Negro effort alone. He ridiculed the assumption that the Communist Party, aligned with the political course of the Soviet Union, could pursue a constructive policy with regard to Negro interests here.

(8) Philip Randolph, statement made on the proposed March on Washington (15th January, 1941)

Negro America must bring its power and pressure to bear upon the agencies and representatives of the Federal Government to exact their rights in National Defense employment and the armed forces of the country. I suggest that ten thousand Negroes march on Washington, D. C. with the slogan: "We loyal Negro American citizens demand the right to work and fight for our country." No propaganda could be whipped up and spread to the effect that Negroes seek to hamper defense. No charge could be made that Negroes are attempting to mar national unity. They want to do none of these things. On the contrary, we seek the right to play our part in advancing the cause of national defense and national unity. But certainly there can be no national unity where one tenth of the population are denied their basic rights as American citizens.

(9) On 18th June, 1941, a meeting took place at the White House about the proposed March on Washington. This included Philip Randolph, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Walter White and Fiorello La Guardia.

Philip Randolph: Mr. President, time is running on. You are quite busy, I know. But what we want to talk with you about is the problem of jobs for Negroes in defense industries. Our people are being turned away at factory gates because they are colored. They can't live with this thing. Now, what are you going to do about it?

Franklin D. Roosevelt: Well, Phil, what do you want me to do?

Philip Randolph: Mr. President, we want you to do something that will enable Negro workers to get work in these plants.

Franklin D. Roosevelt: Why, I surely want them to work, too. I'll call up the heads of the various defense plants and have them see to it that Negroes are given the same opportunity to work in defense plants as any other citizen in the country.

Philip Randolph: We want you to do more than that. We want something concrete, something tangible, definite, positive, and affirmative.

Franklin D. Roosevelt: What do you mean?

Philip Randolph: Mr. President, we want you to issue an executive order making it mandatory that Negroes be permitted to work in these plants.

Franklin D. Roosevelt: Well Phil, you know I can't do that. If I issue an executive order for you, then there'll be no end to other groups coming in here and asking me to issue executive orders for them, too. In any event, I couldn't do anything unless you called off this march of yours. Questions like this can't be settled with a sledge hammer.

Philip Randolph: I'm sorry, Mr. President, the march cannot be called off.

Franklin D. Roosevelt: How many people do you plan to bring?

Philip Randolph: One hundred thousand, Mr. President.

Franklin D. Roosevelt: Walter, how many people will really march?

Walter White: One hundred thousand, Mr. President.

Fiorello La Guardia: Gentleman, it is clear that Mr. Randolph is not going to call off the march, and I suggest we all begin to seek a formula.

(10) Philip Randolph, statement on the cancellation of the March on Washington (25th June, 1941)

The march has been called off because its main objective, namely the issuance of an Executive Order banishing discrimination in national defense, was secured. The Executive Order was issued upon the condition that the march be called off.

(11) George Schuyler, Pittsburgh Courier (1st August, 1942)

Mr. Randolph knows how to appeal to the emotions of the people and to get a great following together, but there his leadership ends because he has nowhere to lead them and would not know if he had. He has the messianic complex, considerable oratorical ability and some understanding of the plight of the masses, but the leadership capacity and executive ability required for the business at hand is simply not there. The original March on Washington move is now admitted to have been a failure else the current agitation would not be necessary.

(12) Philip Randolph, speech at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (28th August, 1963)

We are not an organization or a group of organizations. We are not a mob. We are the advance guard of a massive moral revolution for jobs and freedom. The revolution reverberates throughout the land, touching every city, every town, every village where blacks are segregated, oppressed and exploited. But this civil rights demonstration is not confined to the Negro; nor is it confined to civil rights; for our white allies knew that they cannot be free while we are not. And we know that we have no future in which six million black and white people are unemployed, and millions more live in poverty. Those who deplore our militancy, who exhort patience in the name of a false peace, are in fact supporting segregation and exploitation. They would have social peace at the expense of social and racial justice. They are more concerned with easing racial tensions than enforcing racial democracy.

(13) Philip Randolph, interviewed by Jervis Anderson for his book, Philip Randolph: A Biographical Portrait (1972)

I have always been opposed to wars in principle - though in the case of World War II, I am able to support those that are vital to the survival of our democratic institutions. Vietnam does not seem to me to be such a war. It represents, as far as I can see, no defence of our vital national interests. The moral commitment of the American government went beyond the reaches of liberal concern for our own problems, in the sense that it committed an enormous and costly amount of the nation's resources to Vietnam - in terms of both money and human life.