The Republican Party

The Republican Party was established at Ripon, Wisconsin in 1854 by a group of former members of the Whig Party, the Free-Soil Party and the Democratic Party. Its original founders were opposed to slavery and called for the repeal of the Kansas-Nebraska and the Fugitive Slave Law. Early members thought it was important to place the national interest above sectional interest and the rights of individual States.

Over the next few years the Republican Party emerged as the main opposition party to the Democratic Party in the North. However, it had little support in the South. The party's first presidential candidate was John C. Fremont in 1856 who won 1,335,264 votes but was defeated by the Democratic Party candidate, James Buchanan.

John C. Fremont was seen as too radical by the electorate and in 1860 the party decided to select the more moderate, Abraham Lincoln, as candidate. Lincoln won the election by 1,866,462 votes (18 free states). His opponents were Stephen A. Douglas (1,375,157 - 1 slave state), John Beckenridge (847,953 - 13 slave states) and John Bell (589,581 - 3 slave states).

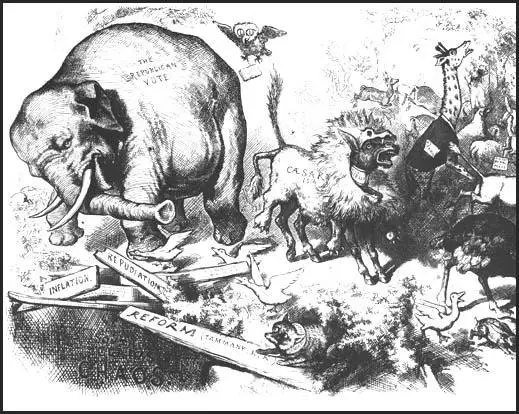

In the 1860s, Thomas Nast, of Harper's Weekly, developed the idea of the political cartoon. Nast originated the idea of using animals to represent political parties. In his cartoons the Democratic Party was a donkey and the Republican Party, an elephant.

After the American Civil War the Republican Party dominated the political system. Its support of protective tariffs gained it the support of powerful industrialists and the Northern urban areas. It was also popular with Northern and Midwestern farmers and most of the immigrant groups, except for the Irish, who tended to support the Democratic Party.

Republican presidents included Ulysses Grant (1869-1877), Rutherhood Hayes (1877-1881), James Garfield (1881) and Chester Arthur (1881-1885). Grover Cleveland managed two victories (1885-89 and 1893-97) for the Democratic Party, but the Republican dominance was reinforced by the election of Benjamin Harrison (1889-1893), William McKinley (1897-1901), Theodore Roosevelt (1901-1909), William Taft (1909-1913), Warren Harding (1921-1923), Calvin Coolidge (1923-1929) and Herbert Hoover (1929-33).

Hoover was blamed for the Economic Depression and in 1932 was defeated by Franklin D. Roosevelt. He held power from 1933 to his death in 1945 and the Democrats remained in power under Harry S. Truman (1945-53).

The Republicans selected the war hero, Dwight D. Eisenhower as its candidate in 1952. During the election the Republicans took a strong anti-communist stance and advocated lower taxes for the rich. It also opposed civil rights legislation being proposed by the liberal Democratic Party candidate, Adlai Stevenson. Eisenhower won by 33,936,252 votes to 27,314,922.

Eisenhower's vice-president, Richard Nixon was narrowly defeated in 1960 by John F. Kennedy (1961-1963) who was followed by another Democrat, Lyndon B. Johnson (1963-1969).

Richard Nixon won two elections (1969-74) but was forced to resign over the Watergate Scandal. Other recent Republican presidents include Gerald Ford (1974-1977) and Ronald Reagan (1981-1989).

Primary Sources

(1) Abraham Lincoln, debate with Stephen Douglas in Alton, Illinois (15th October, 1858)

Stephen Douglas assumes that I am in favor of introducing a perfect social and political equality between the white and black races. These are false issues. The real issue in this controversy is the sentiment on the part of one class that looks upon the institution of slavery as a wrong, and of another class that does not look upon it as a wrong. One of the methods of treating it as a wrong is to make provision that it shall grow no larger.

(2) Abraham Lincoln, speech at Quincy, Illinois (1858)

We have in this nation the element of domestic slavery. The Republican Party think it wrong - we think it is a moral, a social, and a political wrong. We think it is wrong not confining itself merely to the persons of the States where it exists, but that it is a wrong which in its tendency, to say the least, affects the existence of the whole nation. Because we thing it wrong, we propose a course of policy that shall deal with it as a wrong. We deal with it as with any other wrong, insofar as we can prevent it growing any larger, and so deal with it that in the run of time there may be some promise of an end to it.

(3) The journalist, Henry Villard, described the Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas debate at Ottawa, Illinois, on 21st August, 1858.

The first joint debate between Douglas and Lincoln, which I attended, took place on the afternoon of August 21, 1858, at Ottawa, Illinois. It was the great event of the day, and attracted an immense concourse of people from all parts of the State.

Senator Douglas was very small, not over four and a half feet height, and there was a noticeable disproportion between the long trunk of his body and his short legs. His chest was broad and indicated great strength of lungs. It took but a glance at his face and head to convince one that they belonged to no ordinary man. No beard hid any part of his remarkable, swarthy features. His mouth, nose, and chin were all large and clearly expressive of much boldness and power of will. The broad, high forehead proclaimed itself the shield of a great brain. The head, covered with an abundance of flowing black hair just beginning to show a tinge of grey, impressed one with its massiveness and leonine expression. His brows were shaggy, his eyes a brilliant black.

Douglas spoke first for an hour, followed by Lincoln for an hour and a half; upon which the former closed in another half hour. The Democratic spokesman commanded a strong, sonorous voice, a rapid, vigorous utterance, a telling play of countenance, impressive gestures, and all the other arts of the practiced speaker.

As far as all external conditions were concerned, there was nothing in favour of Lincoln. He had a lean, lank, indescribably gawky figure, an odd-featured, wrinkled, inexpressive, and altogether uncomely face. He used singularly awkward, almost absurd, up-and-down and sidewise movements of his body to give emphasis to his arguments. His voice was naturally good, but he frequently raised it to an unnatural pitch.

Yet the unprejudiced mind felt at once that, while there was on the one side a skillful dialectician and debater arguing a wrong and weak cause, there was on the other a thoroughly earnest and truthful man, inspired by sound convictions in consonance with the true spirit of American institutions. There was nothing in all Douglas's powerful effort that appealed to the higher instincts of human nature, while Lincoln always touched sympathetic cords. Lincoln's speech excited and sustained the enthusiasm of his audience to the end.

(4) William Seward, speech, Rochester, New York (25th October, 1858)

The Democratic Party derived its strength originally from its adoption of the principles of equal and exact justice to all men. So long as it practised this principle faithfully, it was invulnerable. It became vulnerable when it renounced the principle, and since that time it has maintained itself not by virtue of its own strength, or even of its traditional merits, but because there as yet had appeared in the political field no other party that had the conscience and the courage to take up, and avow, and practice the life-inspiring principle which the Democratic Party surrendered.

At last, the Republican Party had appeared. It avows now, as the Republican Party of 1800 did, in one word, its faith and its works, "Equal and exact justice to all men." The secret of its assured success lies in that very characteristic, which in the mouth of scoffers constitutes its great and lasting imbecility and reproach. It lies in the fact that it is a party of one idea; but that idea is a noble one - an idea that fills and expands all generous souls - the idea of equality - the equality of all men before human tribunals and human laws, as they are equal before the divine tribunal and divine laws.

(5) Carl Schurz, speech to members of the Republican Party in Massachusetts (18th April, 1859)

I wish the words of the Declaration of Independence, "that all men are created free and equal, and are endowed with certain inalienable rights," were inscribed upon every gatepost within the limits of this republic. From this principle the revolutionary fathers derived their claim to independence; upon this they founded the institutions of this country; and the whole structure was to be the living incarnation of this idea.

Shall I point out to you the consequences of a deviation from this principle? Look at the slave states. This is a class of men who are deprived of their natural rights. But this is not the only deplorable feature of that peculiar organization of society. Equally deplorable is it that there is another class of men who keep the former in subjection. That there are slaves is bad; but almost worse is that there are masters.

Are not the masters freemen? No, sir! Where is their liberty of the press? Where is their liberty of speech? Where is the man among them who dares to advocate openly principles not in strict accordance with the ruling system? They speak of a republican form of government, they speak of democracy; but the despotic spirit of slavery and mastership combined pervades their whole political life like a liquid poison. They do not dare to be free lest the spirit of liberty become contagious.

The system of slavery has enslaved them all, master as well as slave. What is the cause of all this? It is that you cannot deny one class of society the full measure of their natural rights without imposing restraints upon your own liberty. If you want to be free, there is but one way - it is to guarantee an equally full measure of liberty to all your neighbors.

(6) Henry Villard reported on the the Republican Party Convention in 1860. Villard supported William H. Seward and was surprised when Abraham Lincoln won the nomination.

I was enthusiastically for the nomination of William H. Seward, who seemed to me the proper and natural leader of the Republican Party ever since his great "irrepressible conflict" speech in 1858. The noisy demonstrations of his followers, and especially of the New York delegation in his favour, had made me sure, too, that his candidacy would be irresistible. I therefore shared fully the intense chagrin of the New York and other State delegations when, on the third ballot, Abraham Lincoln received a larger vote than Seward.

I had not got over the prejudice against Lincoln with which my personal contact with him in 1858 imbued me. It seemed to me incomprehensible and outrageous that the uncouth, common Illinois politician, whose only experience in public life had been service as a member of the State legislature and in Congress for one term, should carry the day over the eminent and tried statesman, the foremost figure, indeed, in the country.

(7) In his book, Life and Times, Frederick Douglass described the 1860 Presidential Election.

The presidential canvass of 1860 was three sided, and each side had its distinctive doctrine as to the question of slavery and slavery extension. We had three candidates in the field. Stephen A. Douglas was the standard bearer of what may be called the western faction of the old divided democratic party, and John C. Breckenridge was the standard-bearer of the southern or slaveholding, faction of that party. Abraham Lincoln represented the then young, growing, and united republican party. The lines between these parties and candidates were about as distinctly and clearly drawn as political lines are capable of being drawn. The name of Douglas stood for territorial sovereignty, or in other words, for the right of the people of a territory to admit or exclude, to establish or abolish, slavery, as to them might seem best. The doctrine of Breckenridge was that slaveholders were entitled to carry their slaves into any territory of the United States and to hold them there, with or without the consent of the people of the territory; that the Constitution of its own force carried slavery and protected it into any territory open for settlement in the United States. To both these parties, factions, and doctrines, Abraham Lincoln and the republican party stood opposed. They held that the Federal Government had the right and the power to exclude slavery from the territories of the United States, and that that right and power ought to be exercised to the extent of confining slavery inside the slave States, with a view to its ultimate extinction.

(8) Robert Toombs, speech in the Georgia legislature (13th November, 1860)

Mr. Lincoln's Republican Party all speak with one voice, and speak trumpet-tongued their fixed purpose to outlaw $4 billion of our property in the territories, and to put it under the ban of the empire in the states where it exists. They declare their purpose to war against slavery until there shall not be a slave in America, and until the African is elevated to a social and political equality with the white man. Lincoln endorses them and their principles, and in his own speeches declares the conflict irrepressible and enduring, until slavery is everywhere abolished.

My countrymen, "if you have nature in you, bear it not." Withdraw yourselves from such a confederacy; it is your right to do so - your duty to do so. I know not why the Abolitionists should object to it, unless they want to torture and plunder you. If they resist this great sovereign right, make another war of independence, for that then will be the question; fight its battles over again - reconquer liberty and independence. as for me, I will take any place in the great conflict for rights which you may assign. I will take none in the federal government during Mr. Lincoln's administration.

(9) General George McClellan, McClellan's Own Story (1887)

Had I been successful in my first campaign, the rebellion would perhaps have been terminated without the immediate abolition of slavery. I believe that the leaders of the radical branch of the Republican Party preferred political control of one section of a divided country to being in the minority in a restored Union. Not only did these people desire the abolition of slavery, but its abolition in such a manner and under such circumstances that the slaves would at once be endowed with the electoral franchise and permanent control thus be secured through the votes of the ignorant slaves.

(10) Samuel Tilden, speech on the Republican Party at a meeting of the Democratic Party in New York (11th March, 1868)

A complete and harmonious restoration of the revolted states would have been effected if the Republican Party had not proved to be totally incapable of acting in the case with any large, wise, or firm statesmanship.

A magnanimous policy would not only have completed the pacification of the country but would have effected a reconciliation between the Republican Party and the white race in the South. Every circumstance favored such a result. The Republican Party possessed all the powers of the government, and held sway over every motive of gratitude, fear, or interest. The Southern people had become thoroughly weary of the contest; more than half of them had been originally opposed to entering into it, and had done so only when nothing was left to them but to choose on which side they would fight.

All that was necessary to heal the bleeding wounds of the country and to allow its languishing industries to revive, was that the Republican Party - which boasts its great moral ideas and its philanthropy - should rise to the moral elevation of an ordinary pugilist and cease to strike its adversary after it was down.