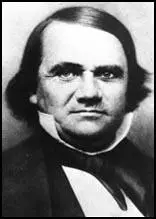

Stephen Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas was born in Brandon, Vermont, in 1813. He became attorney-general of Illinois in 1834, member of the legislature in 1835, secretary of state in 1840, and judge of the supreme court in 1841 and member of the House of Representatives in 1847.

In 1854 Douglas introduced his Kansas-Nebraska bill to the Senate. These states could now enter the Union with or without slavery. Frederick Douglass warned that the bill was "an open invitation to a fierce and bitter strife".

The result of this legislation was to open the territory to organised migrations of pro-slave and anti-slave groups. Southerners now entered the area with their slaves while active members of the Anti-Slavery Society also arrived. Henry Ward Beecher, condemned the bill from his pulpit and helped to raise funds to supply weapons to those willing to oppose slavery in these territories. These rifles became known as Beecher's Bibles. John Brown and five of his sons, were some of the volunteers who headed for Kansas.

In 1858 Abraham Lincoln challenged Douglas for his seat in the Senate. He was opposed to Douglas's proposal that the people living in the Louisiana Purchase (Louisiana, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, Iowa, the Dakotas, Montana, and parts of Minnesota, Colorado and Wyoming) should be allowed to own slaves. Lincoln argued that the territories must be kept free for "poor people to go and better their condition". The two men took part in a series of seven public debates on the issue of slavery.

The debates, each three hours long, started on 21st August and finished on 15th October. Douglas attempted to brand Lincoln as a dangerous radical who was advocating racial equality. Whereas Lincoln concentrated on the immorality of slavery and attempts to restrict its growth.

The Democratic Party that met in Charleston in April, 1860, were deeply divided. Most delegates from the Deep South argued that the Congress had no power to legislate over slavery in their territory. The Northerners disagreed and won the vote. As a result the Southerners walked out of the convention and another meeting was held in Baltimore. Again the Southerners walked out over the issue of slavery. With only the Northern delegates left, Douglas won the nomination.

Southern delegates now held another meeting in Richmond and John Beckenridge was selected as their candidate. The situation was further complicated by the formation of the Constitutional Union Party and the nomination of John Bell of Tennessee.

Abraham Lincoln won the presidential election with with 1,866,462 votes (18 free states) and beat Douglas (1,375,157 - 1 slave state), John Beckenridge (847,953 - 13 slave states) and John Bell (589,581 - 3 slave states). Between election day in November, 1860 and inauguration the following March, seven states seceded from the Union: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas. Stephen Douglas died in 1861.

Primary Sources

(1) The journalist, Henry Villard, described the Stephen A. Douglas and Abraham Lincoln debate at Ottawa, Illinois, on 21st August, 1858.

The first joint debate between Douglas and Lincoln, which I attended, took place on the afternoon of August 21, 1858, at Ottawa, Illinois. It was the great event of the day, and attracted an immense concourse of people from all parts of the State.

Senator Douglas was very small, not over four and a half feet height, and there was a noticeable disproportion between the long trunk of his body and his short legs. His chest was broad and indicated great strength of lungs. It took but a glance at his face and head to convince one that they belonged to no ordinary man. No beard hid any part of his remarkable, swarthy features. His mouth, nose, and chin were all large and clearly expressive of much boldness and power of will. The broad, high forehead proclaimed itself the shield of a great brain. The head, covered with an abundance of flowing black hair just beginning to show a tinge of grey, impressed one with its massiveness and leonine expression. His brows were shaggy, his eyes a brilliant black.

Douglas spoke first for an hour, followed by Lincoln for an hour and a half; upon which the former closed in another half hour. The Democratic spokesman commanded a strong, sonorous voice, a rapid, vigorous utterance, a telling play of countenance, impressive gestures, and all the other arts of the practiced speaker.

As far as all external conditions were concerned, there was nothing in favour of Lincoln. He had a lean, lank, indescribably gawky figure, an odd-featured, wrinkled, inexpressive, and altogether uncomely face. He used singularly awkward, almost absurd, up-and-down and sidewise movements of his body to give emphasis to his arguments. His voice was naturally good, but he frequently raised it to an unnatural pitch.

Yet the unprejudiced mind felt at once that, while there was on the one side a skillful dialectician and debater arguing a wrong and weak cause, there was on the other a thoroughly earnest and truthful man, inspired by sound convictions in consonance with the true spirit of American institutions. There was nothing in all Douglas's powerful effort that appealed to the higher instincts of human nature, while Lincoln always touched sympathetic cords. Lincoln's speech excited and sustained the enthusiasm of his audience to the end.

(2) Stephen A. Douglas, speech in Alton, Illinois (15th October, 1858)

We ought to extend to the negro race all the rights, all the privileges, and all the immunities which they can exercise consistently with the safety of society. Humanity requires that we should give them all these privileges; Christianity commands that we should extend those privileges to them. The question then arises, "What are those privileges, and what is the nature and extent of them?" My answer is, that is a question which each State must answer for itself.

(3) Abraham Lincoln, speech in Alton, Illinois (15th October, 1858)

Stephen Douglas assumes that I am in favor of introducing a perfect social and political equality between the white and black races. These are false issues. The real issue in this controversy is the sentiment on the part of one class that looks upon the institution of slavery as a wrong, and of another class that does not look upon it as a wrong. One of the methods of treating it as a wrong is to make provision that it shall grow no larger.