John Brown

John Brown was born at Torrington, Connecticut, on 9th May, 1800. The family moved to Ohio in 1805 where his father worked as a tanner. John's father was staunchly anti-slavery and was a voluntary agent for the Underground Railroad.

Brown studied for the Congregational ministry in Connecticut but changed his mind and returned to work with his father in Hudson, Ohio. He had a variety of different jobs including work as a tanner, wool merchant, land surveyor and farmer. Married twice, he was the father of twenty children. In 1849 Brown and his family settled in a black community founded in North Elba on land donated by the Anti-Slavery campaigner, Gerrit Smith.

While at North Elba, Brown developed strong opinions about the evils of slavery and gradually became convinced that it would be necessary to use force to overthrow this system. After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850, Brown recruited forty-four men into the United States League of Gileadites, an organization founded to resist slave-catchers.

In 1855 Brown and five of his sons moved to Kansas Territory to help anti-slavery forces obtain control of this region. His home in Osawatomie was burned in 1856 and one of his sons was killed. With the support of Gerrit Smith, Samuel G. Howe, and other prominent Abolitionists, Brown moved to Virginia where he established a refuge for runaway slaves.

In 1859 he led a party of 21 men in a successful attack on the federal armory at Harper's Ferry. Brown hoped that his action would encourage slaves to join his rebellion, enabling him to form an emancipation army. Two days later the armory was stormed by Robert E. Lee and a company of marines. Brown and six men barricaded themselves in an engine-house, and continued to fight until Brown was seriously wounded and two of his sons had been killed.

John Brown was tried and convicted of insurrection, treason and murder. He was executed on 2nd December, 1859. Six other men involved in the raid were also hanged. The song, John Brown's Body, commemorating the Harper's Ferry raid, was a highly popular marching song with Republican soldiers during the American Civil War.

Primary Sources

(1) Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881)

John Brown cautiously approached the subject which he wished to bring to my attention; for he seemed to apprehend opposition to his views. He denounced slavery in look and language fierce and bitter, thought that slaveholders had forfeited their right to live, that the slaves had the right to gain their liberty in any way they could, did not believe that moral suasion would ever liberate the slave, or that political action would abolish the system.

He said that he had long had a plan which could accomplish this end, and he had invited me to his house to lay that plan before me. He said he had been for some time looking for colored men to whom he could safely reveal his secret, and at times he had almost despaired of finding such men, but that now he was encouraged, for he saw heads of such rising up in all directions. He had observed my course at home and abroad, and he wanted my co-operation.

His plan as it then lay in his mind, had much to commend it. It did not, as some suppose, contemplate a general rising among the slaves, and a general slaughter of the slave masters. An insurrection he thought would only defeat the object, but his plan did contemplate the creating of an armed force which should act in the very heart of the south. He was not averse to the shedding of blood, and thought the practice of carrying arms would be a good one for the colored people to adopt, as it would give them a sense of their manhood. No people he said could have self respect, or be respected, who would not fight for their freedom.

(2) John Brown's son, John Brown Jr, gave an interview to Oswald Garrison Villard, about how the family decided to join the campaign against slavery.

After spending considerable time in setting forth, in impressive language, the hopeless condition of the slave, he asked who of us were willing to make common cause with him in doing all in our power to "break the jaws of the wicked and pluck the spoil out of his teeth". Receiving an affirmative answer from each, he kneeled in prayer, and all did the same. After prayer he asked us to raise our right hands, and he then administered an oath bound us to secrecy and devotion to the purpose of fighting slavery by force and arms to the extent of our ability.

(3) New York Herald (21st October, 1859)

Brown is fifty-five years of age, rather small-sized, with keen and restless gray eyes, and a grizzly beard and hair. He is a wiry, active man, and should the slightest chance for an escape be afforded, there is no doubt that he will yet give his captors much trouble. His hair is matted and tangled, and his face, hands, and clothes are smutched and smeared with blood.

Colonel Lee stated that he would exclude all visitors from the room if the wounded men were annoyed or pained by them, but Brown said he was by no means annoyed; on the contrary, he was glad to be able to make himself and his motives clearly understood. He converses freely, fluently, and cheerfully, without the slightest manifestation of fear or uneasiness, evidently weighing well his words, and possessing a good command of language. His manner is courteous and affable, while he appears to be making a favorable impression upon his auditory, which, during most of the day yesterday averaged about ten or a dozen men.

When I arrived in the armory, shortly after two o'clock in the afternoon, Brown was answering questions put to him by Senator Mason, who had just arrived from his residence at Winchester, thirty miles distant. Colonel Faulkner, member of Congress who lives but a few miles off, Mr. Vallandigham, member of Congress of Ohio, and several other distinguished gentlemen. The following is a verbatim report of the conversation:

Mr. Mason: Can you tell us, at least, who furnished the money for your expedition?

Mr. Brown: I furnished most of it myself. I cannot implicate others. It is by my own folly that I have been taken. I could easily have saved myself from it had I exercised my own better judgment rather than yield to my feelings. I should have

gone away, but I had thirty-odd prisoners, whose wives and daughters were in tears for their safety, and I felt for them. Besides, I wanted to allay the fears of those who believed we came here to burn and kill. For this reason I allowed the train to cross the bridge and gave them full liberty to pass on. I did it only to spare the feelings of these passengers and their families and to allay the apprehensions that you had got here in your vicinity a band of men who had no regard for life and property, nor any feeling of humanity.

Mr. Mason: But you killed some people passing along the streets quietly.

Mr. Brown: Well, sir, if there was anything of that kind done, it was without my knowledge. Your own citizens, who were my prisoners, will tell you that every possible means were taken to prevent it. I did not allow my men to fire, nor even to return a fire, when there was danger of killing those we regarded as innocent persons, if I could help it. They will tell you that we allowed ourselves to be fired at repeatedly and did not return it.

A Bystander: That is not so. You killed an unarmed man at the comer of the house over there (at the water tank) and another besides.

Mr. Brown: See here, my friend, it is useless to dispute or contradict the report of your own neighbors who were my prisoners.

Mr. Mason: If you would tell us who sent you here - who provided the means - that would be information of some value.

Mr. Brown: I will answer freely and faithfully about what concerns myself - I will answer anything I can with honor,

but not about others.

Mr. Vallandigham (member of Congress from Ohio, who had just entered): Mr. Brown, who sent you here?

Mr. Brown: No man sent me here; it was my own prompting and that of my Maker, or that of the devil, whichever you

please to ascribe it to. I acknowledge no man (master) in human form.

Mr. Vallandigham: Did you get up the expedition yourself?

Mr. Brown: I did.

Mr. Mason: What was your object in coming?

Mr. Brown: We came to free the slaves, and only that.

A Young Man (in the uniform of a volunteer company): How many men in all had you?

Mr. Brown: I came to Virginia with eighteen men only, besides myself.

Volunteer: What in the world did you suppose you could do here in Virginia with that amount of men?

Mr. Brown: Young man, I don't wish to discuss that question here.

Volunteer: You could not do anything.

Mr. Brown: Well, perhaps your ideas and mine on military subjects would differ materially.

Mr. Mason: How do you justify your acts?

Mr. Brown: I think, my friend, you are guilty of a great wrong against God and humanity. I say it without wishing to be offensive - and it would be perfectly right for anyone to interfere with you so far as to free those you willfully and wickedly hold in bondage. I do not say this insultingly. I think I did right and that others will do right who interfere with you at any time and all times. I hold that the golden rule, "Do unto others as you would that others should do unto you," applies to all who would help others to gain their liberty.

(4) While waiting for his trial to take place, John Brown was interviewed by William A. Phillips, of the New York Tribune (1859)

One of the most interesting things in his conversation that night, and one that marked him as a theorist, was his treatment of our forms of social and political life. He thought society ought to be organized on a less selfish basis; for while material interests gained something by the deification of pure selfishness, men and women lost much of it. He said that all great reforms, like the Christian religion, were based on broad, generous, self-sacrificing principles.

(5) John Brown, speech in court after being sentenced to death (December, 1859)

Had I interceded in the manner which I admit, and which I admit has been fairly proved, had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends, either father, mother, sister, wife or children, or any of that class, and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been right. Every man in the court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.

(6) Henry David Thoreau, A Plea for Captain John Brown (1859)

I read all the newspapers I could get within a week after this event, and I do not remember in them a single expression of sympathy for these men. I have since seen one noble statement, in a Boston paper, not editorial. Some voluminous sheets decided not to print the full report of Brown's words to the exclusion of other matter.

But I object not so much to what they have omitted as to what they have inserted. Even the Liberator called it "a misguided, wild, and apparently insane-effort." As for the herd of newspapers and magazines, I do not chance to know an editor in the country who will deliberately print anything which he knows will ultimately and permanently reduce the number of his subscribers.

A man does a brave and humane deed, and at once, on all sides, we hear people and parties declaring, "I didn't do it, nor countenance him to do it, in any conceivable way. It can't be fairly inferred from my past career." I, for one, am not interested to hear you define your position. I don't know that I ever was or ever shall be. I think it is mere egotism, or impertinent at this time. Ye needn't take so much pains to wash your skirts of him. No intelligent man will ever be convinced that he was any creature of yours. He went and came, as he himself informs us, "under the auspices of John Brown and nobody else."

Prominent and influential editors, accustomed to deal with politicians, men of an infinitely lower grade, say, in their ignorance, that he acted "on the principle of revenge." They do not know the man. They must enlarge themselves to conceive of him. I have no doubt that the time will come when they will begin to see him as he was. They have got to conceive of a man of faith and of religious principle, and not a politician or an Indian; of a man who did not wait till he was personally interfered with or thwarted in some harmless business before he gave his life to the cause of the oppressed.

I wish I could say that Brown was the representative of the North. He was a superior man. He did not value his bodily life in comparison with ideal things. He did not recognize unjust human laws, but resisted them as he was bid. For once we are lifted out of the trivialness and dust of politics into the region of truth and manhood. No man in America has ever stood up so persistently and effectively for the dignity of human nature, knowing himself for a man, and the equal of any and all governments. In that sense he was the most American of us all. He needed no babbling lawyer, making false issues, to defend him. He was more than a match for all the judges that American voters, or office-holders of whatever grade, can create. He could not have been tried by a jury of his peers, because his peers did not exist.

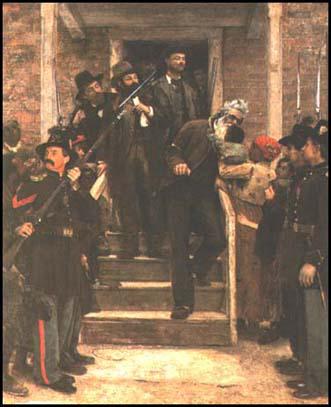

(7) Thomas Stonewall Jackson watched the execution of John Brown on 2nd December, 1859. That night he wrote a letter to his wife about what he had witnessed.

John Brown was hung today. He behaved with unflinching firmness. The gibbet was erected in a large field, south-east of the town. Brown rode on the head of his coffin from the prison to the place of execution. He was dressed in a black frock-coat, black pantaloons, black waistcoat, black slouch hat, white socks, and slippers of predominating red. The open wagon in which he rode was strongly guarded on all sides. Brown had his arms tied behind him, and ascended the scaffold with apparent cheerfulness. After reaching the top of the platform, he shook hands with several who were standing around him. The sheriff placed the rope round his neck, then threw a white cap over his head. In this condition he stood for about ten minutes on the trap-door. Colonel Smith then announced to the sheriff "already", which apparently was not comprehended by him, and the colonel had to repeat the order. Then the rope was cut by a single blow, and Brown dropped several inches, his knees falling to the level occupied by his feet before the rope was cut. With the fall, his arms below the elbows flew up horizontally, his hands clenched; but soon his arms gradually fell by spasmodic motions. There was very little motion for several moments; then the wind started to blow his lifeless body too and fro.

(8) Lucius Bierce, the uncle of Ambrose Bierce, made a speech when John Brown was executed that was reported in the Summit Beacon in Ohio (7th December, 1859)

The tragedy of Brown's is freighted with awful lessons and consequences. It is like the clock striking the fatal hour that begins a new era in the conflict with slavery. Men like Brown may die, but their acts and principles will live forever. Call it fanaticism, folly, madness, wickedness, but until virtue becomes fanaticism, divine wisdom folly, obedience to God madness, and piety wickedness, John Brown, inspired with these high and holy teachings, will rise up before the world with his calm, marble features, most terrible in death and defeat, than in life and victory. It is one of those acts of madness which history cherished and poetry loves forever to adorn with her choicest wreaths of laurel.

(9) Oswald Garrison Villard, John Brown (1910)

He had in mind no well-defined purpose in attacking Harper's Ferry, save to begin his revolution in a spectacular way, capture a few slaveholders and release a few slaves. So far as he had thought anything out, he expected to alarm the town and then, with the slaves that had rallied to him, to march back to the school-house near the Kennedy Farm, arm his recruits and to take to the hills.

(10) Frederick Douglass, speech on John Brown, (May 30, 1881)

The true question is, Did John Brown draw his sword against slavery and thereby lose his life in vain? And to this I answer ten thousand times, No! No man fails, or can fail, who so grandly gives himself and all he has to a righteous cause. No man, who in his hour of extremest need, when on his way to meet an ignominious death, could so forget himself as to stop and kiss a little child, one of the hated race for whom he was about to die, could by any possibility fail.

"Did John Brown fail? Ask Henry A. Wise in whose house less than two years after, a school for the emancipated slaves was taught.

"Did John Brown fail? Ask James M. Mason, the author of the inhuman fugitive slave bill, who was cooped up in Fort Warren, as a traitor less than two years from the time that he stood over the prostrate body of John Brown.

"Did John Brown fail? Ask Clement C. Vallandingham, one other of the inquisitorial party; for he too went down in the tremendous whirlpool created by the powerful hand of this bold invader. If John Brown did not end the war that ended slavery, he did at least begin the war that ended slavery. If we look over the dates, places and men for which this honor is claimed, we shall find that not Carolina, but Virginia, not Fort Sumter, but Harpers Ferry, and the arsenal, not Col. Anderson, but John Brown, began the war that ended American slavery and made this a free Republic. Until this blow was struck, the prospect for freedom was dim, shadowy and uncertain. The irrepressible conflict was one of words, votes and compromises.

"When John Brown stretched forth his arm the sky was cleared. The time for compromises was gone – the armed hosts of freedom stood face to face over the chasm of a broken Union – and the clash of arms was at hand. The South staked all upon getting possession of the Federal Government, and failing to do that, drew the sword of rebellion and thus made her own, and not Brown's, the lost cause of the century.