Watergate

In 1971, G. Gordon Liddy joined the White House Staff. Working under Egil Krogh, Liddy became a member of the Special Investigations Group (SIG). The group was (informally known as "the Plumbers" because their job was to stop leaks from Nixon's administration. Later that year the SIG became concerned about the activities of Daniel Ellsberg. He was a former member of the McNamara Study Group which had produced the classified History of Decision Making in Vietnam, 1945-1968. (1) Ellsberg, disillusioned with the progress of the war, believed this document should be made available to the public. Ellsberg gave a copy of what later became known as the Pentagon Papers to Phil Geyelin of the Washington Post. Katharine Graham and Ben Bradlee decided against publishing the contents on the document.

Ellsberg now went to the New York Times and they began publishing extracts from the document on 13th June, 1971. This included information that Dwight Eisenhower had made a secret commitment to help the French defeat the rebellion in Vietnam. The document also showed that John F. Kennedy had turned this commitment into a war by using a secret "provocation strategy" that led to the Gulf of Tonkin incidents and that Lyndon B. Johnson had planned from the beginning of his presidency to expand the war.

The Pentagon Papers

Ben Bradlee wrote: "Six full pages of news stories and top-secret documents, based on a 47-volume, 7,000-page study, "History of U.S. Decision-Making Process on Vietnam Policy, 1945-1967." The New York Times had obtained a copy of the study, and had assigned more than a dozen top reporters and editors to digest it for three months, and write dozens of articles... We found ourselves in the humiliating position of having to rewrite the competition. Every other paragraph of the Washington Post story had to include some form of the words 'according to the New York Times,' blood - visible only to us - on every word." (2)

Bradlee was criticised by his journalists for failing to break this story. He now made attempts to catch up and on June 18, 1971, the Washington Post began publishing extracts from another copy of the document. However, Bradlee concentrated on the period when Dwight Eisenhower was in power. The first story reported on how the Eisenhower administration had delayed democratic elections in Vietnam. This marked a change in direction and "established Katharine Graham as a great American woman in the 1970s, a leader of the moral opposition to the Nixon administration, the truth of the matter was that her newspaper had done a bad job handling the moral issues of the 1960s, as bad as that of the politicians themselves. The significance of the Pentagon Papers was that they put her belatedly on the right side of the issues." (3)

Richard Nixon now made attempts to prevent anymore extracts from the Pentagon Papers being published. Murray Gurfein, the federal judge who heard the case, ruled: “The security of the nation is not at the ramparts alone. Security also lies in the value of our free institutions. A cantankerous press, an obstinate press, a ubiquitous press must be suffered by those in authority in order to preserve the even greater values of freedom of expression and the right of the people to know.” (4) The Supreme Court ruled against Nixon and Hugo Black commented that the two newspapers "should be commended for serving the purpose that the Founding Fathers saw so clearly". "The next day, both of us resumed our stories about the Pentagon Papers. For the first time in the history of the American republic, newspapers had been restrained by the government from publishing a story - a black mark in the history of democracy. We had won." (5)

Watergate Break-in

In 1972 Gordon Liddy joined the Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP). Later that year Liddy presented Nixon's attorney general, John N. Mitchell, with an action plan called Operation Gemstone. Liddy wanted a $1 million budget to carry out a series of black ops activities against Nixon's political enemies. Mitchell decided that the budget for Operation Gemstone was too large. Instead he gave him $250,000 to launch a scaled-down version of the plan. On 20th March, Liddy and Frederick LaRue attended a meeting of the committee where it was agreed to spend $250,000 "intelligence gathering" operation against the Democratic Party.

One of Liddy's first tasks was to place electronic devices in the Democratic Party campaign offices in an apartment block called Watergate. Liddy wanted to wiretap the conversations of Larry O'Brien, chairman of the Democratic National Committee and R. Spencer Oliver, executive director of the Association of State Democratic Chairmen. This was not successful and on 17th June, 1972, Frank Sturgis, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker and James W. McCord returned to the Watergate offices. However, this time they were caught by the police.

Bob Woodward & Carl Bernstein

Joseph Califano, counsel to both the Democratic Party and the Washington Post, informed Bradlee's team that five men had broken into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee at Watergate. It was decided Bob Woodward should cover the story. "He spent all day behind the police lines, calling in to the city desk regularly with all the vital statistics." When Sturgis, Gonzalez, Martinez, Barker and McCord appeared in court, Woodward was sitting in the front row when he heard McCord being asked what kind of a "retired government worker" he was. McCord replied "CIA". Bradlee later commented: "No three letters in the English language, arranged in that particular order, and spoken in similar circumstances, can tighten a good reporter's sphincter faster than C-I-A". (6) It appeared that the men had been involved in the wiretapping the conversations of Larry O'Brien, chairman of the Democratic National Committee.

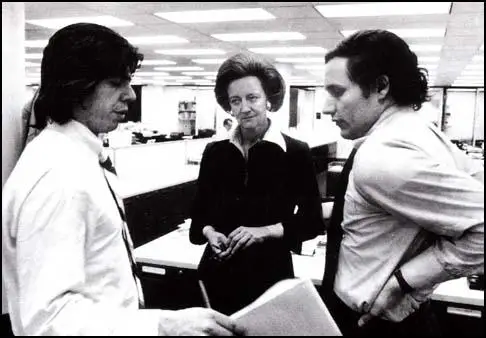

Carl Bernstein was chosen to work with Woodward on the story. Katharine Graham admitted this was a strange choice and the two men had never worked on a story together. "Carl Bernstein... had been at the Washington Post since the fall of 1966 but had not distinguished himself. He was a good writer, but his poor work-habits were well-known throughout the city room even then, as was his famous roving eye. In fact, one thing that stood in the way of Carl's being put on the story was that Ben Bradlee was about to fire him." (7)

The phone number of E.Howard Hunt was found in address books of the burglars. Hunt records in his autobiography, American Spy (2007) that he received a telephone-call from Woodward: "Some men have been arrested, and one of them had your name in his notebook. His name is Barker. Is he a friend of yours?" Hunt admitted that replied without thinking: "Oh my God." (8) Woodward discovered that Hunt, like McCord, was a former officer in the CIA and worked for them from 1949 to 1970. He was currently working as a consultant to Charles Colson, special counsel to President Richard Nixon. Woodward and Bernstein were now able to link the break-in to the White House. (9)

Carroll Kilpatrick, the Washington Post White House correspondent saw a picture of James W. McCord and immediately recognized him as someone who worked for Nixon's reelection committee. Bradlee pointed out: "In less than forty-eight hours, we had traced what the Republicans were calling a 'third-rate burglary' into the White House, and into the very heart of the effort to win Richard Nixon a second term. We didn't know it yet, but we were out front, never to be headed, in the story of our generation, the story that put us all on the map." (10)

Deep Throat

According to Bob Woodward, one of his best sources was a man that was given the nickname of Deep Throat. He claims that on 19th June, he telephoned a man who he called "an old friend" for information about the burglars. This man, who Woodward claims was a high-ranking federal employee, was willing to help Woodward as long as he was never named as a source. During their first telephone conversation Deep Throat insisted on certain conditions. According to All the President's Men: "His identity was unknown to anyone else. He could be contacted only on very important occasions. Woodward had promised he would never identify him or his position to anyone. Further, he, had agreed never to quote the man, even as an anonymous source. Their discussions would be only to confirm information that had been obtained elsewhere and to add some perspective." (11)

Ben Bradlee claims that Deep Throat was Woodward's source. However, Deborah Davis, the author of Katharine the Great (1979), claims this is not true: "Bradlee knew him (Deep Throat), had known him far longer than Woodward. There is a possibility that Woodward had met him while working as an intelligence liaison between the Pentagon and the White House, where Deep Throat spent a lot of time, and that he considered Woodward trustworthy, or useful, and began talking to him when the time was right. It is equally likely, though, that Bradlee, who had given Woodward other sources on other stories, put them in touch after Woodward's first day on the story, when Watergate burglar James McCord said at his arraignment hearing that he had once worked for the CIA." (12) Davis suggests that Deep Throat was Bradlee's CIA friend, Richard Ober. Woodward later identified Deep Throat as Mark Felt, who worked for FBI. (13) However, it is clear from the evidence that Woodward claimed Deep Throat supplied, came from a variety of different sources, including the CIA and the White House. (14)

Carl Bernstein concentrated on researching the background of Bernard L. Barker. Born in Cuba he joined the National Police and worked as an assistant to the Chief of Police with the rank of sergeant. Later he was recruited by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and worked for them as an undercover agent. He also did work for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). When Fidel Castro successfully overthrew Fulgencio Batista, Barker and his family moved to Miami (January 1960). Barker became a significant figure in the Cuban exile community. He remained a CIA agent and worked under the direction of Frank Bender. Later that year Barker was assigned to work under E. Howard Hunt. Barker's new job was to recruit men into the 2506 Brigade. These men eventually took part in the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba.

The Washington Post

Bernstein went to Miami to talk to the prosecutor there who had started his own Watergate investigation. Martin Dardis told Bernstein that he had traced money recovered at the Watergate to the Nixon re-election campaign (CRP). He discovered that a $25,000 check had come from Kenneth H. Dahlberg, a businessman who had been fundraising for Richard Nixon. He told Woodward that he turned over all the money he raised to Maurice Stans, CRP's finance chairman. On 1st August, 1972, the Washington Post ran the story about this connection between the Watergate burglars and Nixon. (15)

On 29th September, Bernstein phoned John N. Mitchell and asked him to comment on a story that he had controlled a "secret fund" when he was Attorney General. Mitchell replied: "All that crap you're putting in the paper. It's all been denied. Katie Graham's going to get her tit caught in a big fat wringer if that's published. Good Christ! That's the most sickening thing I've ever heard... You fellows got a great ball game. As soon as you're through paying Ed Williams and the rest of those fellows, we're going to do a little story on all of you." (16)

Woodward and Bernstein eventually discovered that the FBI had identified large-scale corruption. On 10th October, 1972, the Washington Post reported: "FBI agents have established that the Watergate bugging incident stemmed from a massive campaign of political spying and sabotage conducted on behalf of President Nixon's re-election and directed by officials of the White House and the Committee for the Re-election of the President. The activities, according to information in FBI and Department of Justice files, were aimed at all the major Democratic presidential candidates and - since 1971 - represented a basic strategy of the re-election effort."

The article went on to argue: "During the Watergate investigation federal agents established that hundreds of thousands of dollars in Nixon campaign contributions had been set aside to pay for an extensive undercover campaign aimed at discrediting individual Democratic presidential candidates and disrupting their campaigns... Following members of Democratic candidates' families; assembling dossiers of their personal lives; forging letters and distributing them under the candidates' letterheads; leaking false and manufactured items to the press; throwing campaign schedules into disarray; seizing confidential campaign files and investigating the lives of dozens of campaign workers. In addition, investigators said the activities included planting provocateurs in the ranks of organizations expected to demonstrate at the Republican and Democratic conventions; and investigating potential donors to the Nixon campaign before their contributions were solicited." (17)

On 15th October, 1972, Woodward and Bernstein revealed that Nixon's appointments secretary, Dwight Chaplin, and an ex-White House aide, Donald Segretti, were integral parts of the spying and sabotage operation. Evidence also emerged that others close to Nixon, such as Jeb Magruder, H. R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, were involved in controlling the White House secret fund, used to finance all political sabotage and payoffs. When this information was published, Ben Bradlee was accused of mounting a political smear campaign against Nixon during the 1972 Presidential Campaign.

Bob Dole, the chairman of the Republican Party, made a speech on 23rd October, attacking Bradlee: "The greatest political scandal of this campaign is the brazen manner in which, without benefit of clergy, The Washington Post has set up house-keeping with the McGovern campaign... Now, Mr. Bradlee, an old Kennedy coat-holder, is entitled to his views. But when he allows his paper to be used as a political instrument of the McGovernite campaign; when he himself travels the country as a small-bore McGovern surrogate, then he and his publication should expect appropriate treatment, which they will with regularity receive. The Republican Party has been the victim of a barrage of unfounded and unsubstantiated allegations by George McGovern and his partner in mud-slinging, The Washington Post." (18)

Death of Dorothy Hunt

Frederick LaRue now decided that it would be necessary to pay the large sums of money to secure their silence. LaRue raised $300,000 in hush money. Anthony Ulasewicz, a former New York policeman, was given the task of arranging the payments. This money went to E. Howard Hunt and distributed by his wife Dorothy Hunt. (19) On 8th December, 1972, Hunt took Flight 533 from Washington to Chicago. The aircraft hit the branches of trees close to Midway Airport: "It then hit the roofs of a number of neighborhood bungalows before plowing into the home of Mrs. Veronica Kuculich at 3722 70th Place, demolishing the home and killing her and a daughter, Theresa. The plane burst into flames killing a total of 45 persons, 43 of them on the plane, including the pilot and first and second officers. Eighteen passengers survived." Hunt was killed in the accident. (20)

The airplane crash was blamed on equipment malfunctions. Carl Oglesby, the author of The Yankee and Cowboy War (1977) has pointed out that the day after the crash, Egil Krogh was appointed Undersecretary of Transportation, supervising the National Transportation Safety Board and the Federal Aviation Association - the two agencies charged with investigating the airline crash. A week later, Nixon's deputy assistant Alexander P. Butterfield was made the new head of the FAA, and five weeks later Dwight L. Chapin, the president's appointment secretary, become a top executive with United Airlines. (21)

Watergate Convictions

In January, 1973, Frank Sturgis, E. Howard Hunt, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker, G. Gordon Liddy and James W. McCord were convicted of conspiracy, burglary and wiretapping. On 19th March, 1973, McCord wrote a letter to Judge John J. Sirica claiming that the defendants had pleaded guilty under pressure (from John Dean and John N. Mitchell) and that perjury had been committed. Sirica decided to publish the contents of this letter. "In the interests of justice and in the interests of restoring faith in the criminal justice system, which faith has been severely damaged in this case, I will state the following to you at this time which I hope may be of help to you in meting out justice in this case. 1. There was political pressure applied to the defendants to plead guilty and remain silent. 2. Perjury occurred during the trial in matters highly material to the very structure, orientation and impact of the government's case, and to the motivation and intent of the defendants. 3. Others involved in the Watergate operation were not identified during the trial, when they could have been by those testifying." (22)

On 30th April 1973, Richard Nixon forced two of his principal advisers H. R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, to resign. Richard Nixon later recalled that sacking Haldeman was "the hardest decision I had ever made." Ehrlichman did not take the decision as well as Haldemann. He had been telling Nixon for some time that he should resign. He told Nixon that day: "I have done nothing that was without your implied or direct approval." (23) A third adviser, John Dean, refused to go and was sacked.

Bradlee was seen as partly responsible for these resignations. In his autobiography he pointed out: "April 1973 was probably the worst month ever for the Nixon White House... Magruder told the grand jury that Dean and Mitchell had approved the Watergate bugging. Acting FBI director Patrick Gray was revealed to have destroyed two folders taken from Howard Hunt's safe in the White House, immediately after the Watergate break-in, and was forced to resign in humiliation... A Wall Street Journal poll showed that a majority of Americans now believed that the president knew about the cover-up." (24) On 12th April, The Washington Post won a Pulitzer Prize for its Watergate reporting.

On 20th April, John Dean issued a statement making it clear that he was unwilling to be a "scapegoat in the Watergate case". He told his lawyer: "I've been thinking that maybe I should go public with something. Maybe I should let them know I'm not going to take this lying down." (25) When Dean testified on 25th June, 1973 before the Senate Committee investigating Watergate, he claimed that Richard Nixon participated in the cover-up. He also confirmed that Nixon had tape-recordings of meetings where these issues were discussed. (26)

Ben Bradlee points out that Bob Woodward found out that Alexander Butterfield was in charge of Nixon's "internal security" and suspected he had been responsible for arranging Nixon's secret recordings. He gave this information to "an investigator on the Ervin Committee". He passed this to Samuel Dash and Butterfield was interviewed on 13th July. Late that night, Woodward received a telephone call from the investigator: "We interviewed Butterfield. He told the whole story. Nixon bugged himself." Bradlee commented in his memoirs: "The death knell of Richard Nixon was tolling." (27)

The Special Prosecutor now demanded access to these tape-recordings. At first Nixon refused. Carl Bernstein began calling sources at the White House: "Four of them said they had learned that the tapes were of poor quality, that there were gaps in some conversations. But they did not know whether these had been caused by erasures. Ron Ziegler told Bernstein there were no gaps or erasures in the tapes. However, on 21st November, Nixon's lawyers admitted that one of the tapes had a gap of over 18 minutes. (28)

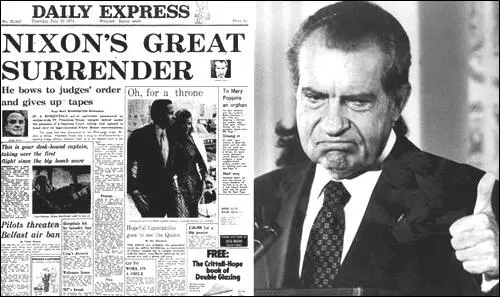

The Supreme Court ruled against Nixon and members of the Senate began calling for him to be impeached, he changed his mind. However, some tapes were missing while others contained important gaps. Under extreme pressure, Nixon supplied tape scripts of the missing tapes.Nixon's secretary, Rose Mary Woods, denied deliberately erasing the tape. It was now clear that Nixon had been involved in the cover-up and members of the Senate began to call for his impeachment. On 9th August, 1974, Richard Nixon became the first President of the United States to resign from office. Nixon was granted a pardon but other members of his staff involved in helping in his deception were imprisoned. Nixon was granted a pardon but several members of his staff involved in the cover-up were imprisoned. This included: H. R. Haldeman, John Ehrlichman, Charles Colson, John Dean, John N. Mitchell, Jeb Magruder, Egil Krogh, Frederick LaRue, Robert Mardian and Dwight L. Chapin.

Ben Bradlee received a lot of the credit for bringing down Richard Nixon. Katharine Graham, the publisher of the The Washington Post, explained the role played by Bradlee: "Woodward and Bernstein clearly were the key reporters on the story - so much so that we began to refer to them collectively as Woodstein - but the cast of characters at the Washington Post who contributed to the story from its inception was considerable. As executive editor, Ben was the classic leader at whose desk the buck of responsibility stopped. He set the ground rules - pushing, pushing, pushing, not so subtly asking everyone to take one more step, relentlessly pursuing the story in the face of persistent accusations against us and a concerted campaign of intimidation." (29)

Christopher Reed has pointed out: "Watergate hurt Washington, but was also cited as proof that its political system worked – eventually. It made stars of the two reporters and thrust newspaper journalism into a heroic new mould.... Bradlee embraced the truth theme fervently ... and taught courses on truth at Harvard and Georgetown universities... It was a curious stance for someone who spent many years undercover as a counter-espionage informant, a government propagandist, and unofficial asset of the Central Intelligence Agency. It started publicly enough with his Pacific war posting as a navy destroyer intelligence officer. Thereafter it became much more more clandestine." (30)

Primary Sources

(1) Richard Nixon, diary entry (June, 1972)

I got the disturbing news from Bob Haldeman that the break-in of the Democratic National Committee involved someone who is on the payroll of the Committee to Re-elect the President. Mitchell had told Bob on the phone enigmatically not to get involved in it, and I told Bob that I simply hoped that none of our people were involved for two reasons - one, because it was stupid in the way it was handled; and two, because I could see no reason whatever for trying to bug the national committee.

(2) H. R. Haldeman, The Ends of Power (1978)

Chuck Colson had become the President's personal 'hit man'; his impresario of 'hard ball' politics. I had been caught in the middle of most of these, as complaints thundered in about 'Wildman' Colson either crashing arrogantly; or sneaking silently, through political empires supposedly controlled by White House staffers such as Domestic Counselor John Ehrlichman or Cabinet Officers such as Attorney General John Mitchell. Colson cared not who complained. Nixon, he said, was his only boss. And Nixon was behind him all the way on projects ranging from his long-dreamed-of hope of catching Senator Teddy Kennedy in bed with a woman not his wife, to more serious struggles such as the I.T.T. anti-trust 'scandal'.

Colson had signed up an ex-C.I.A, agent named Howard Hunt to work for him and thereafter became very secretive about his exploits in the name of Nixon. Years later I heard of such wild schemes as the proposed fire bombing of a politically liberal foundation (Brookings) in order to retrieve a document Nixon wanted; feeding LSD to an anti-Nixon commentator (Jack Anderson) before he went on television; and breaking into the offices of a newspaperman (Hank Greenspun) who was supposed to have documents from Howard Hughes that revealed certain secrets about Nixon.

But Colson's 'black' projects were so widely rumoured around the White House that I believe almost every White House staffer thought of his name the minute they heard the news of Watergate.

(3) Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, Washington Post (19th June, 1972)

One of the five men arrested early Saturday in the attempt to bug the Democratic National Committee headquarters is the salaried security coordinator for President Nixon's reelection committee.

The suspect, former CIA employee James W. McCord Jr., 53, also holds a separate contract to provide security services to the Republican National Committee, GOP national chairman Bob Dole said yesterday.

Former Attorney General John N. Mitchell, head of the Committee for the Re-Election of the President, said yesterday McCord was employed to help install that committee's own security system.

In a statement issued in Los Angeles, Mitchell said McCord and the other four men arrested at Democratic headquarters Saturday "were not operating either in our behalf or with our consent" in the alleged bugging attempt.

Dole issued a similar statement, adding that "we deplore action of this kind in or out of politics." An aide to Dole said he was unsure at this time exactly what security services McCord was hired to perform by the National Committee.

Police sources said last night that they were seeking a sixth man in connection with the attempted bugging. The sources would give no other details.

Other sources close to the investigation said yesterday that there still was no explanation as to why the five suspects might have attempted to bug Democratic headquarters in the Watergate at 2600 Virginia Ave., NW, or if they were working for other individuals or organizations..

"We're baffled at this point.... the mystery deepens," a high Democratic party source said.

Democratic National Committee Chairman Lawrence F. O'Brien said the "bugging incident... raised the ugliest questions about the integrity of the political process that I have encountered in a quarter century.

"No mere statement of innocence by Mr. Nixon's campaign manager will dispel these questions."

The Democratic presidential candidates were not available for comment yesterday.

O'Brien, in his statement, called on Attorney General Richard G. Kleindienst to order an immediate, "searching professional investigation" of the entire matter by the FBI.

A spokesman for Kleindienst said yesterday. "The FBI is already investigating. . . . Their investigative report will be turned over to the criminal division for appropriate action."

The White House did not comment.

McCord, 53, retired from the Central Intelligence Agency in 1970 after 19 years of service and established his own "security consulting firm," McCord Associates, at 414 Hungerford Drive, Rockville. He lives at 7 Winder Ct., Rockville.

McCord is an active Baptist and colonel in the Air Force Reserve, according to neighbors and friends.

In addition to McCord, the other four suspects, all Miami residents, have been identified as: Frank Sturgis (also known as Frank Florini), an American who served in Fidel Castro's revolutionary army and later trained a guerrilla force of anti-Castro exiles; Eugenio R. Martinez, a real estate agent and notary public who is active in anti-Castro activities in Miami; Virgilio R. Gonzales, a locksmith; and Bernard L. Barker, a native of Havana said by exiles to have worked on and off for the CIA since the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961.

All five suspects gave the police false names after being arrested Saturday. McCord also told his attorney that his name is Edward Martin, the attorney said.

Sources in Miami said yesterday that at least one of the suspects - Sturgis - was attempting to organize Cubans in Miami to demonstrate at the Democratic National Convention there next month.

The five suspects, well-dressed, wearing rubber surgical gloves and unarmed, were arrested about 2:30 a.m. Saturday when they were surprised by Metropolitan police inside the 29-office suite of the Democratic headquarters on the sixth floor of the Watergate.

The suspects had extensive photographic equipment and some electronic surveillance instruments capable of intercepting both regular conversation and telephone communication.

Police also said that two ceiling panels near party chairman O'Brien's office had been removed in such a way as to make it possible to slip in a bugging device.

McCord was being held in D.C. jail on $30,000 bond yesterday. The other four were being held there on $50,000 bond. All are charged with attempted burglary and attempted interception of telephone and other conversations.

McCord was hired as "security coordinator" of the Committee for the Re-election of the President on Jan. 1, according to Powell Moore, the Nixon committee's director of press and information.

Moore said McCord's contract called for a "take-home salary of $1,200 per month and that the ex-CIA employee was assigned an office in the committee's headquarters at 1701 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W.

Within the last one or two weeks, Moore said, McCord made a trip to Miami beach -- where both the Republican and Democratic National Conventions will be held. The purpose of the trip, Moore said, was "to establish security at the hotel where the Nixon Committee will be staying."

In addition to McCord's monthly salary, he and his firm were paid a total of $2,836 by the Nixon Committee for the purchase and rental of television and other security equipment, according to Moore.

Moore said that he did not know exactly who on the committee staff hired McCord, adding that it "definitely wasn't John Mitchell." According to Moore, McCord has never worked in any previous Nixon election campaigns "because he didn't leave the CIA until two years ago, so it would have been impossible." As of late yesterday, Moore said. McCord was still on the Re-Election Committee payroll.

In his statement from Los Angeles, former Attorney General Mitchell said he was "surprised and dismayed" at reports of McCord's arrest.

"The person involved is the proprietor of a private security agency who was employed by our committee months ago to assist with the installation of our security system," said Mitchell. "He has, as we understand it, a number of business clients and interests and we have no knowledge of these relationships."

Referring to the alleged attempt to bug the opposition's headquarters, Mitchell said: "There is no place in our campaign, or in the electoral process, for this type of activity and we will not permit it nor condone it."

About two hours after Mitchell issued his statement, GOP National Chairman Dole said, "I understand that Jim McCord... is the owner of the firm with which the Republican National Committee contracts for security services . . . if our understanding of the facts is accurate, added Dole, "we will of course discontinue our relationship with the firm."

Tom Wilck, deputy chairman of communications for the GOP National Committee, said late yesterday that Republican officials still were checking to find out when McCord was hired, how much he was paid and exactly what his responsibilities were.

McCord lives with his wife in a two-story $45,000 house in Rockville.

After being contacted by The Washington Post yesterday, Harlan A. Westrell, who said he was a friend of McCord's, gave the following background on McCord:

He is from Texas, where he and his wife graduated from Baylor University. They have three children, a son who is in his third year at the Air Force Academy, and two daughters.

The McCords have been active in the First Baptist Church of Washington.

Other neighbors said that McCord is a colonel in the Air Force Reserve, and also has taught courses in security at Montgomery Community College. This could not be confirmed yesterday.

McCord's previous employment by the CIA was confirmed by the intelligence agency, but a spokesman there said further data about McCord was not available yesterday.

In Miami, Washington Post Staff Writer Kirk Schartenberg reported that two of the other suspects - Sturgis and Barker - are well known among Cuban exiles there. Both are known to have had extensive contracts with the Central Intelligence Agency, exile sources reported, and Barker was closely associated with Frank Bender, the CIA operative who recruited many members of Brigade 2506, the Bay of Pigs invasion force.

Barker, 55, and Sturgis, 37, reportedly showed up uninvited at a Cuban exile meeting in May and claimed to represent an anticommunist organization of refugees from "captive nations." The purpose of the meeting, at which both men reportedly spoke, was to plan a Miami demonstration in support of President Nixon's decision to mine the harbor of Haiphong.

Barker, a native of Havana who lived both in the U.S. and Cuba during his youth, is a U.S. Army veteran who was imprisoned in a German POW camp during the World War II. He later served in the Cuban Buro de Investigationes - secret police - under Fidel Castro and fled to Miami in 1959. He reportedly was one of the principal leaders of the Cuban Revolutionary Council, the exile organization established with CIA help to organize the Bay of Pigs Invasion.

Sturgis, an American soldier of fortune who joined Castro in the hills of Oriente Province in 1958, left Cuba in 1959 with his close friend, Pedro Diaz Lanz, then chief of the Cuban air force. Diaz Lanz, once active in Cuban exile activities in Miami, more recently has been reported involved in such right-wing movements as the John Birch Society and the Rev. Billy James Hargis' Christian Crusade.

Sturgis, more commonly known as Frank Florini, lost his American citizenship in 1960 for serving in a foreign military force - Castro's army - but, with the aid of then-Florida Sen. George Smathers, regained it.

(4) Richard Nixon, The Memoirs of Richard Nixon (1978)

My reaction to the Watergate break-in was completely pragmatic. If it was also cynical, it was a cynicism born of experience. I had been in politics too long, and seen everything from dirty tricks to vote fraud. I could not muster much moral outrage over a political bugging.

Larry O'Brien might affect astonishment and horror, but he knew as well as I did that political bugging had been around nearly since the invention of the wiretap. As recently as 1970 a former member of Adlai Stevenson's campaign staff had publicly stated that he had tapped the Kennedy organization's phone lines at the 1960 Democratic convention Lyndon Johnson felt that the Kennedys had had him tapped - Barry Goldwater said that his 1964 campaign had been bugged; and Edgar Hoover told me that in 1968 Johnson had ordered my campaign plane bugged. Nor was the practice confined to politicians. In 1969 an NBC producer was fined and given a suspended sentence for planting a concealed microphone at a closed meeting of the 1968 Democratic platform committee. Bugging experts told the Washington Post right after the Watergate break-in that the practice "has not been uncommon in elections past... it is particularly common for candidates of the same party to bug one another."

(5) Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, Washington Post (10th October, 1972)

FBI agents have established that the Watergate bugging incident stemmed from a massive campaign of political spying and sabotage conducted on behalf of President Nixon's re-election and directed by officials of the White House and the Committee for the Re-election of the President.

The activities, according to information in FBI and Department of Justice files, were aimed at all the major Democratic presidential candidates and - since 1971 - represented a basic strategy of the re-election effort.

During the Watergate investigation federal agents established that hundreds of thousands of dollars in Nixon campaign contributions had been set aside to pay for an extensive undercover campaign aimed at discrediting individual Democratic presidential candidates and disrupting their campaigns.

"Intelligence work" is normal during a campaign and is said to be carried out by both political parties. But federal investigators said what they uncovered being done by the Nixon forces is unprecedented in scope and intensity.

Following members of Democratic candidates' families; assembling dossiers of their personal lives; forging letters and distributing them under the candidates' letterheads; leaking false and manufactured items to the press; throwing campaign schedules into disarray; seizing confidential campaign files and investigating the lives of dozens of campaign workers.

In addition, investigators said the activities included planting provocateurs in the ranks of organizations expected to demonstrate at the Republican and Democratic conventions; and investigating potential donors to the Nixon campaign before their contributions were solicited.

(6) Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, The Final Days (1976)

John Dean, the President's former counsel had been fired on April 30 and was now busily leaking stories all over Washington about the Watergate scandal. Some of them hinted that the President was involved in the cover-up. Dean seemed to have some record of White House misdeeds; he told Judge John Sirica that he had removed certain documents from the White House to protect them from "illegitimate destruction". Dean had put them in a safe-deposit box and given the keys to the judge. The New York Times, also citing anonymous informers, said that one of its sources "suggested that Mr. Dean may have tape-recorded some of his White House conversations".

(7) Taped conversation between Richard Nixon and John Dean (21st March, 1973)

John Dean: We have a cancer within, close to the Presidency, that is growing. Basically it is because we are being blackmailed.

Richard Nixon: How much money do you need?

John Dean: I would say these people are going to cost a million dollars over the next two years.

Richard Nixon: You could get a million dollars. You could get it in cash. I know where it could be gotton.

(8) James W. McCord, statement (23rd March, 1973)

In the interests of justice and in the interests of restoring faith in the criminal justice system, which faith has been severely damaged in this case, I will state the following to you at this time which I hope may be of help to you in meting out justice in this case.

1. There was political pressure applied to the defendants to plead guilty and remain silent.

2. Perjury occurred during the trial in matters highly material to the very structure, orientation and impact of the government's case, and to the motivation and intent of the defendants.

3. Others involved in the Watergate operation were not identified during the trial, when they could have been by those testifying...

Following sentencing, I would appreciate the opportunity to talk with you privately in chambers. Since I cannot feel confident in talking with an FBI agent, in testifying before a grand jury whose U.S. attorneys work for the Department of Justice, or in talking with other government representatives, such a discussion would be of assistance to me.

(9) John Dean, statement (20th April, 1973)

To date, I have refrained from making any public comment whatsoever about the Watergate case. Some may hope or think that I will become a scapegoat in the Watergate case. Anyone who believes this does not know me, know the true facts, nor understands our system of justice.

(10) Richard Nixon, private notes made in May, 1974.

(1) Cox had to go. Richardson would inevitably go with him. Otherwise, if we had waited for Cox making a major mistake which in the public mind would give us what appeared to be good cause for him to go would mean that we had waited until Cox had moved against us.

(2) We must learn from the Richardson incident what people we can depend on. Establishment types like Richardson simply won't stand with us when chips are down and they have to choose between their political ambitions and standing by the President who made it possible for them to hold the high positions from which they were now resigning.

(3) As far as the tapes were concerned we need to put the final documents in the best possible PR perspective. We must get out the word with regard to no "doctoring" of the tapes.

(4) We must compare our situation now with what it was on April 30. Then the action with regard to Haldeman and Ehrlichman, Gray, Dean, and Kleindienst did not remove the cloud on the President as far as an impression of guilt on his part was concerned. In fact it increased that doubt and rather than satisfying our critics once they had tasted a little blood they liked it so much they wanted far more. Since April 30 we have slipped a great deal. We had 60 percent approval rating in the polls on that date and now we stand at 30 percent at best.

(5) Now the question is whether our action on turning over the tapes or the transcripts thereof helps remove the cloud of doubt. Also on the plus side, the Mideast crisis, probably if the polls are anywhere near correct, helped some what because it shows the need for RN's leadership in foreign policy.

(6) Our opponents will now make an all-out push. The critical question is whether or not the case for impeachment or resignation is strong enough in view of the plus factors I noted in previous paragraph.

(11) Bob Woodward memo to Ben Bradlee (16th May, 1973)

Dean talked with Senator Baker after Watergate committee formed and Baker is in the bag completely, reporting back directly to White House...

President threatened Dean personally and said if he ever revealed the national security activities that President would insure he went to jail.

Mitchell started doing covert national and international things early and then involved everyone else. The list is longer than anyone could imagine.

Caulfield met McCord and said that the President "knows that we are meeting and he offers you executive clemency and you'll only have to spend about 11 months in jail."

Caulfield threatened McCord and said "your life is no good in this country if you don't cooperate..."

The covert activities involve the whole U.S. intelligence community and are incredible. Deep Throat refused to give specifics because it is against the law.

The cover-up had little to do with the Watergate, but was mainly to protect the covert operations.

The President himself has been blackmailed. When Hunt became involved, he decided that the conspirators could get some money for this. Hunt started an "extortion" racket of the rankest kind.

Cover-up cost to be about $1 million. Everyone is involved - Haldeman, Ehrlichman, the President, Dean, Mardian, Caulfield and Mitchell. They all had a problem getting the money and couldn't trust anyone, so they started raising money on the outside and chipping in their own personal funds. Mitchell couldn't meet his quota and... they cut Mitchell loose. ...

CIA people can testify that Haldeman and Ehrlichman said that the President orders you to carry this out, meaning the Watergate cover-up... Walters and Helms and maybe others.

Apparently though this is not clear, these guys in the White House were out to make money and a few of them went wild trying.

Dean acted as go-between between Haldeman-Ehrlichman and Mitchell-LaRue.

The documents that Dean has are much more than anyone has imagined and they are quite detailed.

Liddy told Dean that they could shoot him and/or that he would shoot himself, but that he would never talk and always be a good soldier.

Hunt was key to much of the crazy stuff and he used the Watergate arrests to get money... first $100,000 and then kept going back for more...

Unreal atmosphere around the White House - realizing it is curtains on one hand and on the other trying to laugh it off and go on with business. President has had fits of "dangerous" depression.

(12) Richard Nixon, The Memoirs of Richard Nixon (1978)

Over the past months I had talked about resignation with my family with a few close friends, and with Haig and Ziegler. But the idea was anathema to me. I believed that my resignation under pressure would change our whole form of government. The change might not be apparent for many years; but once the first President had resigned under fire and thereby established a precedent, the opponents of future Presidents would have a formidable new leverage. It was not hard to visualize a situation in which Congress, confronted with a President it did not like could paralyze him by blocking him on legislation, foreign affairs and appointments. Then, when the country was fed up with the resulting stalemate, Congress could claim that it would be better for the country if the President resigned. And Nixon would be cited as the precedent. By forcing Presidents out through resignation, Congress would no longer have to take the responsibility and bear the verdict of history for voting impeachment.

(13) Richard Nixon, diary entry (20th April, 1974)

I realize that these transcripts will provide grist for many sensational stories in the press. Parts will seem to be contradictory with one another and parts will be in conflict with some of the testimony given in the Senate Watergate Committee hearings.

I have been reluctant to release these tapes not just because they will embarrass me and those with whom I have talked - which they will - and not just because they will become the subject of speculation and even ridicule - which they will - and not just because certain parts of them will be seized upon by political and journalistic opponents - which they will.

I have been reluctant because, in these and in all the other conversations in this office, people have spoken their minds freely, never dreaming that specific sentences or even parts of sentences would be picked out as the subjects of national attention and controversy.

I am confident that the American people will see these transcripts for what they are, fragmentary records from a time more than a year ago that now seems very distant, the records of a President and of a man suddenly being confronted and having to cope with information which, if true, would have the most far-reaching consequences not only for his personal reputation but, more important, for his hopes, his plans, his goals for the people who had elected him as their leader.

In giving you these records - blemishes and all - I am placing my trust in the basic fairness of the American people.

I know in my own heart that through the long, painful, and difficult process revealed in these transcripts I was trying in that period to discover what was right and to do what was right.

(14) Richard Nixon, The Memoirs of Richard Nixon (1978)

I called Steve Bull, who had greeted Goldwater and his colleagues in the West Lobby. "Take the boys into the office," I said, "and make them comfortable until I get over."

They were all seated when I arrived: Barry Goldwater, the former standard-bearer and now the silver-haired patriarch of the party; Hugh Scott, the Senate Republican Leader, and John Rhodes, the House Republican Leader. Over the years I had shared many successes and many failures with these men. Now they were here to inform me of the bleakness of the situation, and to narrow my choices. I pushed back my chair, put my feet up on the desk, and asked them how things looked.

Scott said that they had asked Goldwater to be their spokesman. In a measured voice Goldwater began, "Mr. President, this isn't pleasant, but you want to know the situation, and it isn't good."

I asked how many would vote for me in the Senate. "Half a dozen?" I ventured.

Goldwater's answer was maybe sixteen or perhaps eighteen.

Puffing on his unlighted pipe, Scott guessed fifteen. "It's pretty grim," he said, as one by one he ran through a list of old supporters, many of whom were now against me. Involuntarily I winced at the names of men I had worked to help elect, men who were my friends.

(15) Richard Nixon, The Memoirs of Richard Nixon (1978)

I asked St. Clair how long he thought we could take to turn over the sixty-four tapes covered by the decision. He said that with all the problems involved in listening to them and preparing transcripts, we could probably take a month or more.

I thought that we should assess the damage right away. When Haig called Buzhardt to discuss the decision, I took the phone and asked him to listen to the June 23 tape and report back to Haig as soon as possible. This was the tape I had listened to in May on which Haldeman and I discussed having the CIA limit the FBI investigation for political reasons rather than the national security reasons I had given in my public statements. When I first heard it, I knew it would be a problem for us if it ever became public - now I would find out just how much of a problem.

Buzhardt listened to the tape early in the afternoon. When he called back, he told Haig and St. Clair that even though it was legally defensible, politically and practically it was the "smoking gun" we had been fearing.

On Thursday, August 1, I told Haig that I had decided to resign. If the June 23 tape was not explainable, I could not very well expect the staff to explain and defend it.

(16) Richard Nixon resignation speech (9th August, 1974)

In the past few days ... it has become evident to me that I no longer have a strong enough political base in the Congress to justify continuing that effort. As long as there was such a base, I felt strongly that it was necessary to see the constitutional process through to its conclusion, that to do otherwise would be unfaithful to the spirit of that deliberately difficult process, and a dangerously destabilizing precedent for the future.

But with the disappearance of that base, I now believe that the constitutional purpose has been served, and there is no longer a need for the process to be prolonged.

Therefore, I shall resign the presidency effective at noon tomorrow. By taking this action, I hope that I will have hastened the start of that process of healing which is so desperately needed in America.

I regret deeply any injuries that may have been done in the course of the events that led to this decision. I would say only that if some of my judgments were wrong - and some were wrong - they were made in what I believed at the time to be in the best interest of the nation.

I have done my very best in all the days since to be true to that pledge. As a result of these efforts. I am confident that the world is a safer place today, not only for the people of America, but for the people of all nations, and that all of our children have a better chance than before of living in peace rather than dying in war. This, more than anything, is what I hoped to achieve when I sought the presidency. This, more than anything, is what I hope will be my legacy to you, to our country, as I leave the presidency.

(17) Peter Dale Scott, Deep Politics and the Death of JFK (1993)

The Watergate break-in of 1972 (in which, I have always been convinced, Nixon was not so much a guilty perpetrator as a guilty victim) followed Nixon's secret negotiations with Hanoi for disengagement from Vietnam, significantly advanced by his May 1972 visit to Moscow, where he signed the first Strategic Arms Limitation Agreement.

(18) Several years after being imprisoned for the Watergate incident, Eugenio Martinez, wrote an account entitled Mission Impossible.

We Cubans have never stopped fighting for the liberation of our country. I have personally carried out over 350 missions to Cuba for the CIA. Some of the people I infiltrated there were caught and tortured, and some of them talked.

My mother and father were not allowed to leave Cuba. It would have been easy for me to get them out. That was my specialty. But my bosses in the Company - the CIA - said I might get caught and tortured, and if I talked I might jeopardize other operations. So my mother and father died in Cuba. That is how orders go. I follow the orders.

I can't help seeing the whole Watergate affair as a repetition of the Bay of Pigs. The invasion was a fiasco for the United States and a tragedy for the Cubans. All of the agencies of the U.S. government were involved, and they carried out their plans in so ill a manner that everyone landed in the hands of Castro - like a present.

Eduardo was a name that all of us who had participated in the Bay of Pigs knew well. He had been the maximum representative of the Kennedy administration to our people in Miami. He occupied a special place in our hearts because of a letter he had written to his chief Cuban aide and my lifelong friend, Bernard Barker. He had identified himself in his letter with the pain of the Cubans, and he blamed the Kennedy administration for not supporting us on the beaches of the Bay of Pigs.

So when Barker told me that Eduardo was coming to town and that he wanted to meet me, that was like a hope for me. He had chosen to meet us at the Bay of Pigs monument, where we commemorate our dead, on April 16, 1971, the tenth anniversary of the invasion. I always go to the monument on that day, but that year I had another purpose - to meet Eduardo, the famous Eduardo, in person.

He was different from all the other men I had met in the Company. He looked more like a politician than a man who was fighting for freedom. He was there with his pipe, relaxing in front of the memorial, and Barker introduced me. I then learned his name for the first time - Howard Hunt.

There was something strange about this man. His tan, you know, is not the tan of a man who is in the sun. His motions are very meticulous--the way he smokes his pipe, the way he looks at you and smiles. He knows how to make you happy--he's very warm, but at the same time you can sense that he does not go all into you or you all into him. We went to a Cuban restaurant for lunch and right away Eduardo told us that he had retired from the CIA in 1971 and was working for Mullen and Company.1 I knew just what he was saying. I was also officially retired from the Company. Two years before, my case officer had gathered all the men in my Company unit and handed us envelopes with retirement announcements inside. But mine was a blank paper. Afterward he explained to me that I would stop making my boat missions to Cuba but I would continue my work with the Company. He said I should become an American citizen and soon I would be given a new assignment. Not even Barker knew that I was still working with the Company. But I was quite certain that day that Eduardo knew.

We talked about the liberation of Cuba, and he assured us that "the whole thing is not over." Then he started inquiring: "What is Manolo doing?" Manolo was the leader of the Bay of Pigs operation. "What is Roman doing?" Roman was the other leader. He said he wanted to meet with the old people. It was a good sign. We did not think he had come to Miami for nothing.

Generally I talk to my CIA case officer at least twice a week and maybe on the phone another two times. I told him right away that Eduardo was back in town, and that I had had lunch with him. Any time anyone from the CIA was in town my CO always asked me what he was doing. But he didn't ask me anything about Eduardo, which was strange. That was in April. In the middle of July, Eduardo wrote to Barker to tell him he was in the White House as a counselor to the President. He sent a number of memos to us on White House stationery, and that was very impressive, you know. So I went back to my CO and said to him, "Hey, Eduardo is still in contact with us, and now he is a counselor of the President."

A few days later my CO told me that the Company had no information on Eduardo except that he was not working in the White House. Well, imagine! I knew Eduardo was in the White House. What it meant to me was that Eduardo was above them and either they weren't supposed to know what he was doing or they didn't want me to talk about him anymore. Knowing how these people act, I knew I had to be careful. So I said, well, let me keep my mouth shut.

Not long after this, Eduardo told Barker there was a job, a national security job dealing with a traitor of this country who had given papers to the Russian Embassy. He said they were forming a group with the CIA, the FBI, and all the agencies, and that it was to be directed from within the White House, with jurisdiction to operate where all the others did not fit. Barker said Eduardo needed two more individuals and he had thought of me. Would I like my name submitted for clearance? I said yes.

To me this was a great honor. I believed it was the result of my sacrifice for the previous ten years, for my work with the Company. In that time I had carried out hundreds of missions for the U.S. government. All of them had been covert, and most were very dangerous. Three or four days later, Barker told me my name had been cleared and several weeks after that came the first assignment. "Get clothes for two or three days and be ready tomorrow," he said. "We're leaving for the operation."

Barker didn't tell me where we were going and I did not ask. I was an operative. I couldn't afford to be aware of any more sensitive information than was critical for the success of my missions. There would be times when I would take men wearing hoods to Cuba. They might have been my friends. But I did not want to know. Too many of my friends have been caught and tortured and forced to talk. In this kind of work you learn to lose your curiosity.

So it was not until I got to the airport in Miami that I discovered we were going to Los Angeles. There were three of us on the mission. The third man, Felipe de Diego, was a real-estate partner of ours. He is an old Company man and a Bay of Pigs veteran whom we knew we could trust.

In all my years in this country I had never been out of the Miami area before that day. I had always been on twenty-four-hour call. I kind of expected my CO to ask where I was going, but he simply said it was fine for me to take a few days off, that there wasn't much to do at the time. I sort of thought he did not want to know what I was doing.

We stayed at the Beverly Hills Hotel and met in Eduardo's room for our only briefing. As we walked in I noticed the equipment - devices to modify the voice, wigs and fake glasses, false identification. Eduardo told us all these things belonged to the Company. Barker recognized the name on Hunt's false identification - Edward J. Hamilton - as the same cover name Eduardo had used during the Bay of Pigs.

The briefing was not like anything I was used to in the Company. Ordinarily, before an operation, you have a briefing and then you train for the operation. You try to find a place that looks similar and you train in disguise and with the code you are going to use. You try out the plan many times so that later you have the elasticity to abort the operation if the conditions are not ideal.

Eduardo's briefing was not like this. There wasn't a written plan, not even any mention of what to do if something went wrong. There was just the man talking about the thing. We were to get into an office to take photographs of psychiatric records of a traitor. I was to be the photographer. The next day we went to Sears and bought some little hats and uniforms for Barker and Felipe. They were supposed to dress up as delivery men and deliver the photographic equipment inside the office. Later that night we would break in and complete the mission.

They looked kind of queerish when they put on the clothes, the Peter Lorre-type glasses, and the funny Dita Beard wigs. But that was not my responsibility, so I waited in the car while they went to the office of Dr. Fielding to deliver the package. Just before leaving Barker had whispered to me: "Hey, remember this name - Ellsberg." Eduardo had told him the name, and he told me because he was worried he would forget it. The name meant nothing to me.

Barker and Felipe were supposed to put the bag inside the office, unlatch the back door, and come out. After the cleaning lady left, we were to go back in. Now, it happened that we had to wait for hours and hours because no one had figured out when the cleaning woman would leave. Finally, I believe, a gentleman came in a car and picked her up.

So at last we went to open the door - and what happened? The door was locked. Barker went around to see if the other door was open, and after a long wait he still did not show up. We didn't know what to do. There had been another man in the briefing the night before in Eduardo's room who hadn't said anything. Later, I learned it was probably Gordon Liddy, but at the time I only knew him as George. Just at that moment, he came up to us and said, "Okay, you people go ahead and force one of the windows and go in."

Eduardo had given us a small crowbar and a glass cutter. I tried to cut the glass, but it wouldn't cut. It was bad, bad. It would not cut anything! So then I taped the window and I hit it with this very small crowbar, and I put my hand in and unlocked the window.

According to the police, we were using gloves and didn't leave any fingerprints. But I'm afraid that I did because I didn't wear my gloves when I put the tape on the window - you know, sometimes it's hard to use gloves. I went all through the offices with my bare hands but I used my handkerchief to wipe off the prints.

Inside the doctor's office we covered the windows and took out the equipment. Really, it was a joke. They had given us a rope to bail out from the second floor if anyone surprised us; it was so small, it couldn't have supported any of us.

This was nothing new. It's what the Company did in the Bay of Pigs when they gave us old ships, old planes, old weapons. They explained that if you were caught in one of those operations with commercial weapons that you could buy anywhere, you could be said to be on your own. They teach you that they are going to disavow you. The Company teaches you to accept those things as the efficient way to work. And we were grateful. Otherwise we wouldn't have had any help at all. In this operation it seemed obvious - they didn't want it to be traced back to the White House. Eduardo told us that if we were caught, we should say we were addicts looking for drugs.

I had just set up the photographic equipment when we heard a noise. We were afraid. Then we heard Barker's familiar knock and we let him in. I took a Polaroid picture of the office before we started looking for the Ellsberg papers so we could put everything back just as it was before. But there was nothing of Ellsberg's there. There was nothing about psychiatry, no one file of sick people, only bills. It looked like an import-export office more than a psychiatrist's. The only thing with the name of Ellsberg in it was the doctor's telephone book. I took a photo of this so that we could bring something back. Before leaving I took some pills from Dr. Fielding's briefcase--vitamin C, I think--and spread them all over the floor to make it look like we were looking for drugs. Eduardo was waiting for us outside. He was supposed to be keeping watch on Dr. Fielding so he could let us know if the doctor was returning to his office, but Eduardo had lost Dr. Fielding and he was nervous. A police car appeared as we drove away and it trailed behind us for three or four blocks. I thought to myself that the police car was protecting us. That is the feeling you have when you are doing operations for the government. You think that every step has been taken to protect you.

Back at the hotel, Barker, Felipe, and I felt very bad. It was our first opportunity, and we had failed; we hadn't found anything. "Yes, I know, but they don't know it," Eduardo said, and he congratulated us all. He said, "Well done," and then he opened a bottle of champagne. And he told us, "This is a celebration. You deserve it."

I told Diego and Barker that this had to have been a training mission for a very important mission to come or else it was a cover operation. I thought to myself that maybe these people already had the papers of Ellsberg. Maybe Dr. Fielding had given them out and for ethical reasons he needed to be covered. It seemed that these people already had what we were looking for because no one invites you to have champagne and is happy when you fail.

The whole thing was strange, but Eduardo was happy so we were happy. He thanked us and we left for the airport. We took the plane back to Miami and we never talked about this thing until we were all together in the District of Columbia jail. In Miami I again told my CO about Eduardo. I was certain then that the Company knew about his activities. But once again my CO did not pursue the subject.

Meanwhile, Hunt started to do more and more things that convinced us of his important position in the White House. Once he called Barker and told him the President was about to mine Haiphong Harbor. He asked us to prepare letters and a rally of support in advance. It was very impressive to us when the announcement of the mining was made several days later.

I made a point of telling my CO at our next meeting that Hunt was involved in some operations and that he was in the White House, even if they said he wasn't. After that the CIA chief of the Western Hemisphere asked me for breakfast at Howard Johnson's on Biscayne Boulevard, and he said he was interested in finding out about Howard Hunt's activities. He wanted me to write a report. He said I should write it in my own hand, in Spanish, and give it to my CO in a sealed envelope. Right away I went to see my CO. We are very close, my CO and I, and he told me that his father had once given him the advice that he should never put anything in writing that might do him any harm in the future. So I just wrote a cover story for the whole thing. I said that Hunt was in the Mullen Company and the White House and things like that that weren't important. What I really thought was that Hunt was checking to see if I could be trusted.

Little by little I watched Eduardo's operation grow. First Barker was given $89,000 in checks from Mexican banks to cash for operational money. And then Eduardo told Barker to recruit three more men, including a key man. He signed up Frank Sturgis and Reinaldo Pico, and then Eduardo flew down to talk to our friend Virgilio Gonzales, who is a locksmith, before recruiting him. Finally orders come for us to report to Washington. The six of us arrived in Washington on May 22 and checked into the Manger Hay-Adams Hotel in time for Eduardo's first briefing.

By that time Liddy, whom we had known as George from the Fielding break-in, was taking a visible role in the planning. Eduardo had started calling him "Daddy," and the two men seemed almost inseparable. We met McCord there for the first time. Eduardo said he was an old man from the CIA who used to do electronic jobs for the CIA and the FBI. We did not know his whole name. Eduardo just introduced him as Jimmy. He said we would be using walkie-talkies, and Jimmy was to be our electronics expert. There was also a boy there who had infiltrated the McGovern headquarters.

There was no mention of Watergate at that meeting. Eduardo told us he had information that Castro and other foreign governments were giving money to McGovern, and we were going to find the evidence. The boy was going to help them break into the McGovern headquarters, but I did not pay much attention. They didn't need me for that operation so I had some free time.

During the day I went off to see the different sights around Washington. I like those things--particularly the John Paul Jones monument and the Naval Academy in Annapolis. Remember that, prior to this, all of my operations for the United States were maritime. After three days Eduardo aborted the McGovern operation. I think it was because the boy got scared. Anyway, Eduardo told us all to move into the Watergate Hotel to prepare for another operation. We brought briefcases and things like that to look elegant. We registered as members of the Ameritus Corporation of Miami, and then we met in Eduardo's room.

Believe me, it was an improvised briefing. Eduardo told us he had information that Castro money was coming into the Democratic headquarters, not McGovern's, and that we were going to try to find the evidence there. Throughout the briefing, McCord, Liddy, and Eduardo would keep interrupting each other, saying, "Well, this way is better," or, "That should be the other way around."

It was not a very definite plan that was finally agreed upon, but you are not too critical of things when you think that people over you know what they are doing, when they are really professionals like Howard Hunt. The plan called for us to hold a banquet for the Ameritus Corporation in a private dining room of the Watergate. The room had access to the elevators that ran up to the sixth floor where the Democratic National Committee Headquarters are located. Once the meal was underway, Eduardo was to show films and we were to take the elevator to the sixth floor and complete the mission. Gonzales, our key man, was to open the door; Sturgis, Pico, and Felipe were to be lookouts; Barker was to get the documents; I was to take the photographs and Jimmy (McCord) was to do his job.

We were all ready to go, but the people in the DNC worked late. Eduardo was drinking lots of milk. He has ulcers, so he was mixing his whiskey with the milk. We waited and waited. Finally, at 2:00 a.m., the night guards said we had to leave the banquet hall. So then there was a discussion. Eduardo said he would hide in the closet of the banquet room with Gonzales, the key man, while the guard let the rest of us out. As soon as the coast was clear, they would let us back in. But then they couldn't open the door. It is difficult for me to tell you this story. I do not want it to become a laughing matter. More than thirty people are in jail already, and a lot of people are suffering. I spent more than fifteen months in jail, and you must understand that this is a tragedy. It is not funny. But you can imagine Eduardo, the head of the mission, in the closet. He did not sleep the whole night. It was really a disaster.

So, more briefings, and we decided to go the next night. This time the plan was to wait until all the lights had gone out on the sixth floor of the Watergate and then go in through the front door.

They gave us briefcases, and I remember that there was a Customs tag hanging on Eduardo's case, so I pulled it off for him. He got real mad. He said that every time he did something he did it with a purpose. I could not see the purpose, but then I don't know. Maybe the tag had an open sesame command to let us in the doors.

Anyway, all seven of us in McCord's army walked up to the Watergate complex at midnight. McCord rang the bell, and a policeman came and let us in. We all signed the book, and McCord told the man we were going to the Federal Reserve office on the eighth floor. It all seemed funny to me. Eight men going to work at midnight. Imagine, we sat there talking to the police. Then we went up to the eighth floor, walked down to the sixth--and do you believe it, we couldn't open that door, and we had to cancel the operation.

I don't believe it has ever been told before, but all the time while we were working on the door, McCord would be going to the eighth floor. It is still a mystery to me what he was doing there. At 2:00 a.m. I went up to tell him about our problems, and there I saw him talking to two guards. What happened? I thought. Have we been caught? No, he knew the guards. So I did not ask questions, but I thought maybe McCord was working there. It was the only thing that made sense. He was the one who led us to the place and it would not have made sense for us to have rooms at the Watergate and go on this operation if there was not someone there on the inside. Anyway, I joined the group, and pretty soon we picked up our briefcases and walked out the front door.

Eduardo was furious that Gonzales hadn't been able to open the door. Gonzales explained he didn't have the proper equipment, so Eduardo told him to fly back to Miami to get his other tools. Before he left the next day, Barker told Gonzales that he might have to pay for his own flight back to Miami. I really got mad and told Barker I resented the way they were treating Gonzales. I was a little hard with Barker. I said there wasn't adequate operational preparation. There was no floor plan of the building; no one knew the disposition of the elevators, how many guards there were, or even what time the guards checked the building. Gonzales did not know what kind of door he was supposed to open. There weren't even any contingency plans.

Barker came back to me with a message from Eduardo: "You are an operative. Your mission is to do what you are told and not to ask questions."

Gonzales got back from Miami that night with his whole shop. I've never seen so many tools to open a door. No door could hold him. This time everything worked. Gonzales and Sturgis picked the lock in the garage exit door; once inside, they opened the other doors and called over the walkie-talkie: "The horse is in the house." Then they let us in. I took a lot of photographs--maybe thirty or forty--showing lists of contributors that Barker had handed me. McCord worked on the phones. He said his first two taps might be discovered, but not the third.

With our mission accomplished, we went back to the hotel. It was about 5:00 a.m. Eduardo said he was happy. But this time there was no champagne. He said we should leave for Miami right away. I gave him the film I had taken and we left for the airport. There were things that bothered me about the operation, but I was satisfied. It is rare that you are able to check the effect of your work in the intelligence community. You know, they don't tell you if something you did is very significant. But we had taken a lot of pictures of contributions, and I had hopes that we might have done something valuable. We all had heard rumors in Miami that McGovern was receiving money from Castro. That was nothing new. We believe that today.

A couple of weeks later I was talking with Felipe de Diego and Frank Sturgis at our real-estate office when Barker burst in like a cyclone. Eduardo had been in town, and he had given Barker some film to have developed and enlarged. Barker did not know what the film was, and he had taken it to a regular camera shop. And then Eduardo had told him it was the film from the Watergate operation. Barker was really excited. He needed us to come with him to get it back. So we went to Rich's Camera Shop, and Barker told Frank and me to cover each door to the shop in case the police came while he was inside. I do not think he handled the situation very well. There were all these people and he was so excited. He ended up tipping the man at the store $20 or $30. The man had just enlarged the pictures showing the documents being held by a gloved hand and he said to Barker: "It's real cloak-and-dagger stuff, isn't it?" Later that man went to the FBI and told them about the film.

My reaction was that it was crazy to have those important pictures developed in a common place in Miami. But Barker was my close friend, and I could not tell him how wrong the whole thing was. The thing about Barker was that he trusted Eduardo totally. He had been his principal assistant at the Bay of Pigs, Eduardo's liaison with the Cubans, and he still believed tremendously in the man. He was just blind about him.

It was too much for me. I talked it over with Felipe and Frank, and decided I could not continue. I was about to write a letter when Barker told me Eduardo wanted us to get ready for another operation in Washington.

When you are in this kind of business, and you are in the middle of something, it is not easy to stop. Everyone will feel that you might jeopardize the operation. "What to do with this guy now?" I knew it would create a big problem so I agreed to go on this last mission.

Eduardo told us to buy surgical gloves and forty rolls of film with thirty-six exposures on a roll. Imagine, that meant 1,440 photographs. I told Barker it would be impossible to take all those pictures. But it did seem to mean that what we got before encouraged Eduardo to go back for more.

We flew into National Airport about noon on June 16, and Barker and I went off to rent a car. In the airport lobby, Frank Sturgis ran into Jack Anderson, whom he had known since the Bay of Pigs, when Anderson wrote a column about him as a soldier-adventurer. Frank introduced Gonzales to Anderson, and he gave him some kind of excuse about why he was in town.

On our way to the Watergate, we made some jokes about the car Barker had rented. It gave me a premonition of a hearse. The mission was not one I was looking forward to.

Eduardo was waiting for us at the Watergate. This time he had two operations planned, and we were supposed to perform them both that night. There was no time for anything, it was all rush.

We went to eat at about five o'clock. Barker ate a lot and when he came back he felt really bad. I was not feeling too good myself. I had just gotten my divorce that day and had gone from the court to the airport and from the airport to the Watergate. The environment in each one of us was different, but the whole thing was bad; there was tension in those people.

Liddy was already in the room when Eduardo came in to give the briefing. Eduardo was wearing loafers and black pants with white stripes. They were very shiny. Liddy was not happy with those pants. He criticized them in front of us and he told Eduardo to go change them.

So Eduardo went and changed his pants. The briefing he gave when he came back was very simple. He said we were going to photograph more documents at the Democratic headquarters and then move on to another mission at the McGovern headquarters after that. McCord was critical of the second operation. He said he didn't like the plan. It was very rare to hear McCord talking because usually he didn't say anything and when he did talk he only whispered.