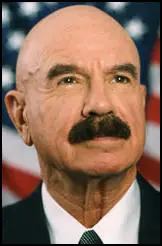

G. Gordon Liddy

George Gordon Liddy was born on 30th November, 1930. After graduating from Fordham University in 1952 he joined the United States Army and served in Korea. Liddy later returned to Fordum to obtain a law degree.

In 1957 Liddy joined the Federal Bureau of Investigation. He remained in the organization until returning to legal work in 1962. Liddy was appointed as Assistant Attorney General, Dutchess County, New York, in 1966. One of his first tasks was to arrange the arrest and prosecution of Timothy Leary.

A member of the Republican Party, in 1968 Liddy failed in his attempt to get the House of Representatives nomination for the 28th District of New York. Liddy now decided to help Richard Nixon in his attempts to become president. Liddy's efforts were rewarded with being appointed as a lawyer in the Treasury Department.

In 1971, Liddy joined the White House Staff. Working under Egil Krogh, Liddy became a member of the Special Investigations Group (SIG). The group was (informally known as "the Plumbers" because their job was to stop leaks from Nixon's administration).

Later that year the SIG became concerned about the activities of Daniel Ellsberg. He was a former member of the McNamara Study Group which had produced the classified History of Decision Making in Vietnam, 1945-1968. Ellsberg, disillusioned with the progress of the war, believed this document should be made available to the public. Ellsberg gave a copy of what later became known as the Pentagon Papers to Phil Geyelin of the Washington Post. Katharine Graham and Ben Bradlee decided against publishing the contents on the document.

Daniel Ellsberg now went to the New York Times and they began publishing extracts from the document on 13th June, 1971. This included information that Dwight Eisenhower had made a secret commitment to help the French defeat the rebellion in Vietnam. The document also showed that John F. Kennedy had turned this commitment into a war by using a secret "provocation strategy" that led to the Gulf of Tonkin incidents and that Lyndon B. Johnson had planned from the beginning of his presidency to expand the war.

On 3rd September, 1971, Liddy and E. Howard Hunt supervised the burglary of a psychiatrist who had been treating Ellsberg. The main objective was to discover incriminating or embarrassing information to discredit Ellsberg. Another project involved the stealing of certain documents from the safe of Hank Greenspun, the editor of the Las Vegas Sun. Later, James W. McCord claimed that Greenspun was being targeted because of his relationship with Robert Maheu and Howard Hughes.

In 1972 Liddy joined the Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP). Later that year Liddy presented Nixon's attorney general, John N. Mitchell, with an action plan called Operation Gemstone. Liddy wanted a $1 million budget to carry out a series of black ops activities against Nixon's political enemies. Mitchell decided that the budget for Operation Gemstone was too large. Instead he gave him $250,000 to launch a scaled-down version of the plan.

On 28th May, 1972, McCord and his team broke into the DNC's offices and placed bugs in two of the telephones. It became the job of Alfred Baldwin to eavesdrop the phone conversations. Over the next 20 days Baldwin listened to over 200 phone calls. These were not recorded. Baldwin made notes and typed up summaries. Nor did Baldwin listen to all phone calls coming in. For example, he took his meals outside his room. Any phone calls taking place at this time would have been missed.

It soon became clear that the bug on one of the phones installed by James W. McCord was not working. As a result of the defective bug, McCord decided that they would have to break-in to the Watergate office again. He also heard that a representative of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War had a desk at the DNC. McCord argued that it was worth going in to see what they could discover about the anti-war activists. Liddy later claimed that the real reason for the second break-in was “to find out what O’Brien had of a derogatory nature about us, not for us to get something on him.”

The original operation was unsuccessful and on 17th June, 1972, McCord, Frank Sturgis, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez and Bernard L. Barker returned to O'Brien's office. However, this time they were caught by the police.

The phone number of E.Howard Hunt was found in address books of the burglars. Reporters were now able to link the break-in to the White House. Bob Woodward, a reporter working for the Washington Post was told by a friend who was employed by the government, that senior aides of President Richard Nixon, had paid the burglars to obtain information about its political opponents.

Frederick LaRue now decided that it would be necessary to pay the large sums of money to secure their silence. LaRue raised $300,000 in hush money. Tony Ulasewicz, a former New York policeman, was given the task of arranging the payments.

In 1972 Nixon was once again selected as the Republican presidential candidate. On 7th November, Nixon easily won the the election with 61 per cent of the popular vote. Soon after the election reports by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of the Washington Post, began to claim that some of Nixon's top officials were involved in organizing the Watergate break-in.

On 30th January, 1973, Liddy, Frank Sturgis, E. Howard Hunt, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker, and James W. McCord were convicted of conspiracy, burglary and wiretapping. Liddy was sentenced to 20 years in prison but served only four years before President Jimmy Carter ordered his release.

Over the next few years Liddy became a writer and a radio talk show host. The G. Gordon Liddy Show was broadcast on 232 stations nationwide. His autobiography, Will: The Autobiography of G. Gordon Liddy, was published in 1982. Liddy has also appeared on several television shows including Miami Vice (1985), Password (1992) and Politically Incorrect (1997).

In 1992 John Dean began legal action against Liddy. Dean objected to information that appeared in books by Liddy (Will: The Autobiography of G. Gordon Liddy) and Len Colodny (Silent Coup) that claimed that Dean was the mastermind of the Watergate burglaries and the true target of the break-in was to destroy information implicating him and his wife in a prostitution ring. The case was dismissed by the U.S. District Court in Baltimore after jurors could not reach a verdict. The publisher of Silent Coup settled a similar suit by Dean and his wife for an unknown amount of money.

In 2002 Liddy published When I Was a Kid, This Was a Free Country. This was followed by Fight Back: Tackling Terrorism Liddy Style (2007).

G. Gordon Liddy died on 30th March, 2021.

Primary Sources

(1) Carl Oglesby, The Yankee and Cowboy War (1976)

Howard Hughes's name surfaced in the story of Watergate on May 20, 1973, when James McCord told the Ervin committee and its media audience of an abandoned 1972 White House plot to steal certain documents from the safe of editor Hank Greenspun's Las Vegas Sun. Greenspun was an ally of Robert Maheu, the top Hughes aide who connected the CIA and the Mafia in 1960, who came to prominence in the Hughes empire during the Las Vegas period, and who then lost out in the Las Vegas power struggle that violently reconfigured the Hughes empire late in 1970. McCord testified that his fellow Plumbers, Hunt and Liddy, were to have carried out the break-in and theft of the papers and that Hughes interests were to have supplied them with a getaway plane and a safe hideout in an unnamed Central American country.

What could the Greenspun documents have been? Why should both Hughes and Nixon have been interested enough in them to attempt a robbery?

Liddy said (testified McCord) that Attorney General John Mitchell had told him that Greenspun had in his possession blackmail type information involving a Democratic candidate for President, that Mitchell wanted that material, and Liddy said that this information was in some way racketeer-related, indicating that if this candidate became President, the racketeers or national crime syndicate could have a control or influence over him as President. My inclination at this point in time, speaking as of today, is to disbelieve the allegation against the Democratic candidate referred to above and to believe that there was in reality some other motive for wanting to get into Greenspun's safe.

(2) G. Gordon Liddy, Will: The Autobiography of G. Gordon Liddy (1980)

The proceedings were held in John Sirica's courtroom. I was charged with two counts of burglary, two of intercepting wire communications, one of intercepting oral communications, and the one all-important charge of "conspiracy." The latter meant little more than planning to do the former, but it is always included by prosecutors when possible to deprive the defendant of much of the protection against use of mere hearsay as evidence. I used to do the same thing.

John Sirica, then Chief Judge by virtue of seniority, had assigned the case to himself only the day before, and I wanted to get a look at him. The proceedings were over so quickly, however, that all I could tell was that he was short and squat with a tendency to play to the press.

My mother put up the required 10 percent of my $10,000 bail and after greeting my codefendants warmly, signing a few papers, and checking the reporting requirements with the probation office, I surrendered my official passport to the clerk of the court and went home. I recalled having read something about Sirica a few years before in Washingtonian magazine. It had long since been discarded but I found a copy of the September 1970 issue in the library.

In an article on the Washington judiciary, Harvey Katz had reported on Sirica's careless, slipshod performance on the bench. He gave the examples of cases where Sirica was reversed: "he is reversed for the most incredible reasons. In one case, he ordered the suit transferred to the federal district court in Minnesota without having first determined whether suit could have been brought there. I was in court when he considered a similar matter. The defendant was seeking a transfer of the case to Houston, claiming that most of the witnesses were there. Plaintiff contended that there were as many witnesses and documents in Washington and New Orleans, and that the case should remain here. "All right, all right," Sirica said. "The case is transferred to New Orleans." Both lawyers had to tell him that no one wanted the case tried there. "Well, Houston, then," Sirica said. "Or wherever."

"Boy," I said to Peter Maroulis, "we drew some judge - a bookthrower with the intellect of half a glass of water."

"Count your blessings," said Peter. I knew what he meant: the combination of Sirica's ill temper, little education, and carelessness increased the chances for reversible error considerably, and that was the only chance we had. It didn't really matter though; trial was set for 15 November, and that was after the election.

(3) Jeb Stuart Magruder, An American Life (1974)

Once again Dean joined us, and once again we had an inconclusive talk with Mitchell. Liddy had not specified the targets for wiretapping, but in discussion we agreed that priority should go to Larry O'Brien's office at the Democratic National Committee in the Watergate complex, to O'Brien's hotel suite in Miami Beach during the Democratic Convention, and to the campaign headquarters of whoever became the Democratic nominee for President. O'Brien had emerged in the past year as the Democrats' most effective spokesman and critic of our Administration.

Liddy still wanted to use call girls in Washington, but the others of us were skeptical and discouraged that plan. We agreed that we should have the capacity to break up hostile demonstrations, and that we needed agents who could get us information on possible disruptions at our convention. Mitchell was still concerned about the plan's price tag and told Liddy he should cut back on his costs, then we could discuss the plan again.

Mitchell, during the discussion, told Liddy that he had information that a Las Vegas newspaper publisher, Hank Greenspun, had some documents in his office that would be politically damaging to Senator Muskie. Mitchell said he would like very much to know whether these documents could be obtained. Liddy beamed and said he'd check out the situation.

So the second meeting ended with Liddy's plan still dangling. None of us was quite comfortable with it, yet all of us felt that some sort of intelligence-gathering program was needed. We knew the daily pressures from the White House for political intelligence, and I think we had a sense that this was how the game was played. During the discussion of wiretapping and break-ins, John Dean had said: "I think it is inappropriate for this to be discussed with the Attorney General. I think that in the future Gordon should discuss his plans with Jeb, then Jeb can pass them on to the Attorney General."

(4) Bob Woodward memo to Ben Bradlee (16th May, 1973)

Dean talked with Senator Baker after Watergate committee formed and Baker is in the bag completely, reporting back directly to White House...

President threatened Dean personally and said if he ever revealed the national security activities that President would insure he went to jail.

Mitchell started doing covert national and international things early and then involved everyone else. The list is longer than anyone could imagine.

Caulfield met McCord and said that the President "knows that we are meeting and he offers you executive clemency and you'll only have to spend about 11 months in jail."

Caulfield threatened McCord and said "your life is no good in this country if you don't cooperate..."

The covert activities involve the whole U.S. intelligence community and are incredible. Deep Throat refused to give specifics because it is against the law.

The cover-up had little to do with the Watergate, but was mainly to protect the covert operations.

The President himself has been blackmailed. When Hunt became involved, he decided that the conspirators could get some money for this. Hunt started an "extortion" racket of the rankest kind.

Cover-up cost to be about $1 million. Everyone is involved - Haldeman, Ehrlichman, the President, Dean, Mardian, Caulfield and Mitchell. They all had a problem getting the money and couldn't trust anyone, so they started raising money on the outside and chipping in their own personal funds. Mitchell couldn't meet his quota and... they cut Mitchell loose. ...

CIA people can testify that Haldeman and Ehrlichman said that the President orders you to carry this out, meaning the Watergate cover-up... Walters and Helms and maybe others.

Apparently though this is not clear, these guys in the White House were out to make money and a few of them went wild trying.

Dean acted as go-between between Haldeman-Ehrlichman and Mitchell-LaRue.

The documents that Dean has are much more than anyone has imagined and they are quite detailed.

Liddy told Dean that they could shoot him and/or that he would shoot himself, but that he would never talk and always be a good soldier.

Hunt was key to much of the crazy stuff and he used the Watergate arrests to get money... first $100,000 and then kept going back for more...

Unreal atmosphere around the White House - realizing it is curtains on one hand and on the other trying to laugh it off and go on with business. President has had fits of "dangerous" depression.

(5) H. R. Haldeman, The Ends of Power (1978)

The Haldeman Theory of the break-in is as follows: I believe Nixon told Colson to get the goods on O'Brien's connection with Hughes at a time when both of them were infuriated with O'Brien's success in using the I.T.T. case against them.

I believe Colson then passed the word to Hunt who conferred with Liddy who decided the taps on O'Brien and Oliver, the other Hughes' phone, would be their starting point.

I believe the Democratic high command knew the break-in was going to take place, and let it happen. They may even have planted the plainclothesman who arrested the burglars.

I believe that the C.I.A. monitored the Watergate burglars throughout. And that the overwhelming evidence leads to the conclusion that the break-in was deliberately sabotaged. (In this regard, it's interesting to point out that every one of the Hunt-Liddy projects somehow failed, from the interrogation of DeMotte, who was supposed to know all about Ted Kennedy's secret love life and didn't, to Dita Beard, to Ellsberg, to Watergate).

(6) Lawrence Meyer, Washington Post (31st January, 1973)

Two former officials of President Nixon's re-election committee, G. Gordon Liddy and James W. McCord, Jr. were convicted yesterday of conspiracy, burglary and bugging the Democratic Party's Watergate headquarters.

After 16 days of trial spanning 60 witnesses and more than 100 pieces of evidence, the jury found them guilty of all charges against them in just under 90 minutes.

Chief US District Judge John J. Sirica ordered Liddy, who was also a former White House aide, FBI agent and prosecutor, and McCord, a veteran of the CIA and FBI, jailed without bond. Sirica said he would hold a hearing on bail after defense lawyers file formal written motions.

Lawyers for both Liddy and McCord, said they would appeal the convictions, with McCords's layer attacking the conduct of Judge Sirica during the trial.

Five other men who were indicted with Liddy and McCord, including former White House aide and CIA Agent E. Howard Hunt, Jr. pleaded guilty early in the trial to all charges against them.

Liddy, 42, had maintained a calm, generally smiling exterior throughout the trial. He stood impassive, with is arms folded as deputy court clerk LeCount Patterson read the jury's verdict, repeating six times "guilty" for all eight counts against him.

McCord, 53, also showed no emotion as Patterson read the word "guilty" for all eight counts against him.

Liddy, former finance counsel for the Committee for the Reelection of the President, could receive a maximum sentence of 35 years. McCord, former security director for the committee, could receive a maximum sentence of 45 years. Sirica set no day for sentencing.

Before being jailed by deputy US marshals, Liddy embraced his lawyer, Peter L. Maroulis, patted him on the back, and in a gesture that became his trademark in the trail, gave one final wave to the spectators and press before he was led away.

Principal Assistant US Attorney Earl J. Silbert said, after the verdict was returned, that it was "fair and just."

In his final statement to the jury, Silbert told the eight women and four men that "when people cannot get together for political purposes without fear that their premises will be burglarized, their conversations bugged, their phones tapped...you breed distrust, you breed suspicion, you lost confidence, faith and credibility."

Silbert asked the jury to "bring in a verdict that will help restore the faith in the democratic system that has been so damaged by the conduct of these two defendants and their coconspirators."

Despite repeated attempts by Judge Sirica to find out if anyone else besides the seven defendants was involved in the conspiracy, testimony in the trial was largely confined by the prosecution to proving its case against Liddy and McCord, with occasional mention made of the five who had pleaded guilty. The jury, which was sequestered throughout the trial, was never told of the guilty pleas.

When Hunt pleaded guilty Jan 11, Sirica questioned him in an attempt to find out if anyone besides the persons indicted was involved in the conspiracy.

Hunt's lawyer, William O. Bittman, blocked Sirica's questions, saying the prosecution had told him it intended to call Hunt and any other defendant who was convicted to testify before the grand jury.

An apparent purpose of renewed grand jury testimony would be to probed the involvement of others in the bugging. Asked yesterday what steps he now intended to take, Silbert said, "I don't think I'll comment on anything further."

According to testimony in the trial, Liddy was given about $332,000 in campaign funds purportedly to carry out a number of intelligence-gathering assignments given him by deputy campaign direction Jeb Stuart Magruder.

The prosecution said it could account for only about $50,000 of this money, and that it was used to finance the spying operation against the Democratic Party.

In his argument to the jury, Silbert called Liddy the "mastermind, the boss, the money-man" of the operation.

Maroulis, defending Liddy, attempted to put the blame on Hunt, who Maroulis said was Liddy's trusted friend. "From the evidence here, it can well be inferred that Mr. Liddy got hut by that trust," Maroulis said.

McCord's lawyer, Gerald Alch, told the jury that McCord "is the type of man who is loyal to his country and who does what he thinks is right." At one point, Judge Sirica interrupted and told Alch he was only giving his "personal opinion."

Alch criticized Sirica during a recess, saying the Judge "did not limit himself to acting as a judge-he has become in addition, a prosecutor and an investigator ... Not only does he indicate that the defendants are guilty, but that a lot of other people are guilty. The whole courtroom is permeated with a prejudicial atmosphere."

Alch said that "in 15 years of practicing law" he had not been previously interrupted by a judge while giving his final argument.

McCord and Liddy were each convicted of the following counts:

Conspiring to burglarize, wiretap and electronically eavesdrop on the Democratic Party's Watergate headquarters. (Maximum penalty-five years' Imprisonment and a $10,000 fine.)

Burglarizing the Democratic headquarters with the intent to steal the property of another. (Maximum penalty-15 years imprisonment.)

Buglarizing the Democratic headquarters with the intent to unlawfully wiretap and eavesdrop. (Maximum penalty-15 years.)

Endeavoring to eavesdrop illegally. (Maximum penalty-five years' imprisonment and a $10,000 fine.)

In addition, McCord was convicted of two additional counts:

Possession of a device primarily useful for the surreptitious interception or oral communications. (Maximum penalty-five years' imprisonment and a $10,000 fine).

Possession of a device primarily useful for the surreptitious interception of wire communications. (Maximum penalty-five years' imprisonment and a $10,000 fine).

Although the total number of years Liddy could be sentenced to adds up to 50 and McCord's total sentence adds up to 60 years, neither, according to legal sources, can receive consecutive sentences for both burglary counts.

As a result, Liddy's maximum sentence could be 35 years and a $40,.000 fine and McCord's maximum could be 45 years and $60,000 fine.

In addition to Liddy, McCord and Hunt, four men from Miami were named in the indictment - Bernard L. Barker, Frank Sturgis, Virgilio R. Gonzalez and Eugenio R. Martinez.

All four pleaded guilty Jan. 15 to the seven counts with which they were charged.

They face maximum sentences of 40 years in jail and fines of $50,000. The four men were arrested, with McCord, by Washington police in the Democratic Party headquarters at 2:30 a.m. on June 17. The arrests marked the beginning of the Watergate affair.

These five men, dressed in business suits and wearing rubber surgical gloves, had electronic bugging equipment and sophisticated cameras in film. In their possession or their rooms they had $5,300 in $100 bills.

The story unfolded slowly. The day after the arrests, it was learned that one of the five men was the security coordinator for the President's reelection committee. That was McCord, one of the two defendants left in the Watergate trial yesterday.

Two days after the break-in White House consultant Hunt was linked to the five suspects. Hunt pleaded guilty to all counts in the opening days of the trial.

Near the end of July, it was learned that the finance counsel to the Nixon Reelection Committee was fired because he refused to answer FBI questions about the Watergate bugging and break-in. The counsel was Liddy, a former Treasury and White House aide who was the other defendant to remain in the trial.

On Aug. 1, The Washington Post reported that a $25,000 cashier's check intended as a contribution tot he Nixon reelection effort has been deposited in the Miami bank account of one of the Watergate suspects. The General Accounting Office, the investigative arm of Congress, ordered an immediate audit of the Nixon campaign finances.

The audit report concluded that former Commerce Secretary Maurice H. Stans, the chief Nixon fund-raiser, has a possible illegal cash fund of $350,000 in his office safe.

The $25,000 from the cashier's check and another $89,000 from four Mexican checks passed through that fund, the GAO concluded.

Last Friday, the Finance Committee to Re-elect the President pleaded no contest in US District Court to eight violations of the campaign finances law. The complaint charged, among other things, that finance committee officials filed to keep adequate records of payments to Liddy. The committee was fined $8,000.

In September, reports surfaced that a former FBI agent and self-described participant in the bugging had become a government witness in the case. He was Alfred C. Baldwin III, who later was to testify that he monitored wire-tapped conversations for three weeks from a listening post in the Howard Johnson Motor Lodge across the street from the Watergate.

On Sept. 15, the federal indictment against the seven original defendants was returned.

The next day, The Post reported that the $350,000 cash fund kept in the Stans safe was used, in part, as an intelligent - gathering fund. On Sept. 29, The Post reported that sources close to the Watergate investigation said that former Attorney General John N. Mitchell controlled disbursements from the intelligence found or so-called "secret fund."

On Oct. 10, The Post reported that the FBI had concluded that the Watergate bugging was just one incident in a campaign of political sabotage directed by the White House and the Nixon committee.

The story identified Donald H. Segretti, a young California lawyer, as a paid political spy who traveled around the country recruiting others and disrupting the campaigns of Democratic presidential contenders.

Five days later, the President's appointments secretary, Dwight L. Chapin, was identified as a person who hire Segretti and received reports from him. Segretti's other contact was Watergate defendant Hunt. Segretti received about $35,000 in pay for the disruptive activities from Herbert W. Kalmbach, the President's personal attorney, according to federal investigators.

This Monday it was announced that Chapin was resigning his White House job. Segretti was not called as a witness in the trial.

(7) Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, Washington Post (13th June, 1973)

The Watergate prosecutors have a one-page memo addressed to former White house domestic affairs adviser John D. Ehrlichman that described in detail the plans to burglarize the office of Pentagon papers defendant Daniel Ellsberg's psychiatrist, according to government sources.

The memo sent to Ehrlichman by former White House aides David Young and Egil (Bud) Krogh, was dated before the Sept. 3, 1971 burglary of the office of the Beverly Hills psychiatrist, the sources said.

The memo was turned over to the prosecutors by Young, who has been granted immunity from prosecution, the sources said.

The sources confirmed earlier reports that Young will testify that Ehrlichman saw the memo and approved the burglary operation.

Ehrlichman could not be reached directly for comment yesterday, but Frank H. Strickler, one of his attorneys, said: "It has been his consistent position that he had no advance knowledge of the break-in and Mr. Ehrlichman stands by that position."

The burglary was supervised by Watergate conspirators E. Howard Hunt, Jr. and G. Gordon Liddy, who in 1971 were members of the White House special investigations unit called the "plumbers."

The group which was directed by Young and Krogh, was charged with investigating leaks to the news media and had been established in June, 1971, after the publication of the Pentagon Papers by several newspapers.

The memo from Krogh and Young directly contradicts a statement Ehrlichman made to the FBI on April 27. According to a summary of that interview made public May 2, Ehrlichman stated that he "was not told that these individuals (Hunt and Liddy) had broken into the premises of the psychiatrist for Ellsberg until after this incident had taken place. Such activity was not authorized by him, he did not know about this burglary until after it had happened."

In an affidavit released last month, Krogh had given "general authorization to engage in covert activity" to obtain information on Ellsberg.

Reliable sources said that Krogh prepared his affidavit by referring to an incomplete copy of the memo that he and Young sent to Ehrlichman before the burglary. Missing from that copy, the sources said, was the bottom portion in which plans for the burglary were described.

The top portion merely made a general reference to covert activity and Krogh based his affidavit on that, according to the sources.

The sources said the prosecutors have the entire memo and that Krogh, now reminded of its contents, is expected to change his statement, thus adding to the damaging testimony against Ehrlichman.

The sources said that the bottom portion of the memo was apparently removed late last year or early this year to sanitize Korgh's files before Senate confirmation hearings on his nomination as undersecretary of Transportation.

Krogh was confirmed without difficulty. He resigned last month after acknowledging that he approved the burglary operation on Ellsberg's psychiatrist.

(8) Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, All the President's Men (1974)

On Wednesday, March 28, McCord was scheduled to give his first sworn testimony behind closed doors to the seven Senators on the Watergate committee. Bernstein joined dozens of reporters waiting outside the hearing room. The reporters began discussing "leaks" which were bound to come out, and agreed on the dangers of trying to report what would go on inside. It was no longer a matter of "investigative" reporting - evaluating information, putting together pieces in a puzzle, disclosing what had been obscured. They would be merely trying to find out in advance the testimony of witnesses who would eventually take the stand in public. Judging which allegations were hearsay, which first-hand knowledge, and placing them in context would be difficult. Sensational charges and deliberate leaks by interested parties would be hard to evaluate. If some papers or networks searched out leaks, all the reporters would feel bound to compete.

The committee session with McCord lasted four and a half hours. Afterward, Senator Howard Baker of Tennessee, the Republican vice chairman of the committee, announced that McCord had provided "significant information... covering a lot of territory."

Bernstein and Woodward began the ritual phone calls, starting with the Senators. "Okay, I'm going to help you on this one," one told Woodward. "McCord testified that Liddy told him the plans and budget for the Watergate operation were approved by Mitchell in February, when he was still Attorney General. And he said that Colson knew about Watergate in advance."

But, in answer to Woodward's questions, be added that McCord had only secondhand information for his allegations, as well as for his earlier accusations that Dean and Magruder had had prior knowledge.

"However," the Senator said, "he was very convincing."

Bradlee was able to get a second Senator to corroborate the story, and Bernstein received the same version from a staff member.

The next day's story, though calling attention to the hearsay nature of McCord's testimony, quoted the unnamed Senator's evaluation.

The flood of "McCord says" stories continued. McCord appeared again on Thursday, and the reporters went through the same exercise. McCord stated that Liddy had told him that charts outlining the Watergate operation had been shown to Mitchell in February. Three sources gave identical versions of the testimony.

(9) Richard Nixon, Memoirs (1978)

In our conversation on Wednesday morning, June 21, Haldeman told me that Gordon Liddy was "the guy who did this." I asked who Liddy was, and Haldeman said he was the counsel for the finance committee at CRP.. When I said I thought McCord was the man responsible for the break-in, Haldeman said no, it was Liddy; we didn't know what McCord's position was, but everyone seemed to think he would hang tight.

Ehrlichman had come up with the idea of having Liddy confess; he would say he did it because he wanted to be a hero at the CRP. This would have several advantages: it would cut off the Democrats' civil suit and minimize their ability to go on fishing expeditions in the depositions connected with it; it would divert some of the press and political attacks by establishing guilt at a low level instead of letting it be imputed to a high one; and finally, since all the arrested men felt that Liddy had been in charge, once Liddy admitted guilt it wouldn't matter what else they thought because everything would tie back to Liddy. Then, Haldeman said, our people would make an appeal for compassion on the basis that Liddy was a poor misguided kid who read too many spy stories.

I said that after all this was not a hell of a lot of crime and in fact if someone asked me about Ziegler's statement that it was a "third-rate burglary," I was going to say no, it was only a"third-rate attempt at burglary." Haldeman said the lawyers all felt that if Liddy and the arrested men entered a guilty plea they would get only fines and suspended sentences since apparently they were all first offenders.

I said I was for Ehrlichman's plan. We had to assume the truth would come out sooner or later, so if Liddy was the man responsible, he should step up and shoulder the blame. My only reservation, I said, would be if this would involve John Mitchell-in that case I didn't think we could do it. A day earlier Haldeman seemed certain Mitchell was not involved. Now he was not so reassuring. He had already told me that Mitchell was concerned about how far the FBI's investigation was going and thought that someone should go directly to the FBI and get it turned off. Haldeman said, too, that Ehrlichman was afraid that Mitchell might be involved. When Haldeman had all but put the question directly to Mitchell when they had talked earlier that morning, he had received no answer; so he could not be sure whether Mitchell was involved or not. He indicated that Mitchell had seemed a little apprehensive about Ehrlichman's plan because of Liddy's instability and what might happen when Liddy was really put under pressure. In any case, he said, Ehrlichman had just developed the plan that morning, and everyone was going to think about it before anything was done.

I still believed that Mitchell was innocent; I was sure he would never have ordered anything like this. He was just too smart and, besides, he had always disdained campaign intelligence-gathering. But there were two nagging possibilities: I might be wrong and Mitchell might have had some involvement; and even if he had not actually been involved, if we weren't careful he might become so circumstantially entangled that neither he nor we would ever be able to explain the truth. Either way, I hoped that Liddy would not draw him in. I said that taking a rap was done quite often. Haldeman said that we could take care of Liddy and I agreed that we could help him; I was willing to help with money for someone who had thought he was helping me win the election.

I never personally confronted Mitchell with the direct question of whether he had been involved in or had known about the planning of the Watergate break-in. He was one of my closest friends, and he had issued a public denial. I would never challenge what he had said; I felt that if there were something he thought I should know, he would have told me. And I suppose there was something else, too, something I expressed rhetorically months later: "Suppose you call Mitchell ... and Mitchell says, `Yes, I did it,' " I said to Haldeman. "Then what do we say?"

(10) John Simkin, Bernard L. Barker (16th July, 2005)

One of the things that has always intrigued me is the large number of mistakes that were made during the Watergate operation. This is in direct contrast to other Nixon dirty tricks campaigns. Some people have speculated that there were individuals inside the operation who wanted to do harm to Nixon. I thought it might be a good idea to list these 24 “mistakes” to see if we can identify these individuals. Could it have been Bernard Barker?

(1) The money to pay for the Watergate operation came from CREEP. It would have been possible to have found a way of transferring this money to the Watergate burglars without it being traceable back to CREEP. For example, see how Tony Ulasewicz got his money from Nixon. As counsel for the Finance Committee to Re-Elect the President, Gordon Liddy, acquired two cheques that amounted to $114,000. This money came from an illegal U.S. corporate contribution laundered in Mexico and Dwayne Andreas, a Democrat who was a secret Nixon supporter. Liddy handed these cheques to E. Howard Hunt. He then gave these cheques to Bernard Barker who paid them into his own bank account. In this way it was possible to link Nixon with a Watergate burglar.

(2) On 22nd May, 1972, James McCord booked Alfred Baldwin and himself into the Howard Johnson Motor Inn opposite the Watergate building (room 419). The room was booked in the name of McCord’s company. During his stay in this room Baldwin made several long-distance phone calls to his parents. This information was later used during the trial of the Watergate burglars.

(3) On the eve of the first Watergate break-in the team had a meeting in the Howard Johnson Motor Inn’s Continental Room. The booking was made on the stationary of a Miami firm that included Bernard Barker among its directors. Again, this was easily traceable.

(4) In the first Watergate break-in the target was Larry O’Brien’s office. In fact, they actually entered the office of Spencer Oliver, the chairman of the association of Democratic state chairman. Two bugs were placed in two phones in order to record the telephone conversations of O’Brien. In fact, O’Brien never used this office telephone.

(5) E. Howard Hunt was in charge of photographing documents found in the DNC offices. The two rolls of film were supposed to be developed by a friend of James McCord. This did not happen and eventually Hunt took the film to Miami for Bernard Barker to deal with. Barker had them developed by Rich’s Camera Shop. Once again the conspirators were providing evidence of being involved in the Watergate break-in.

(6) The developed prints showed gloved hands holding them down and a shag rug in the background. There was no shag rug in the DNC offices. Therefore it seems the Democratic Party documents must have been taken away from the office to be photographed. McCord later claimed that he cannot remember details of the photographing of the documents. Liddy and Jeb Magruder saw them before being put in John Mitchell’s desk (they were shredded during the cover-up operation).

(7) After the break-in Alfred Baldwin and James McCord moved to room 723 of the Howard Johnson Motor Inn in order to get a better view of the DNC offices. It became Baldwin’s job to eavesdrop the phone calls. Over the next 20 days Baldwin listened to over 200 phone calls. These were not recorded. Baldwin made notes and typed up summaries. Nor did Baldwin listen to all phone calls coming in. For example, he took his meals outside his room. Any phone calls taking place at this time would have been missed.

(8) It soon became clear that the bug on one of the phones installed by McCord was not working. As a result of the defective bug, McCord decided that they would have to break-in to the Watergate office. He also heard that a representative of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War had a desk at the DNC. McCord argued that it was worth going in to see what they could discover about the anti-war activists. Liddy later claimed that the real reason for the second break-in was “to find out what O’Brien had of a derogatory nature about us, not for us to get something on him.”

(9) Liddy drove his distinctive Buick-powered green Jeep into Washington on the night of the second Watergate break-in. He was stopped by a policeman after jumping a yellow light. He was let off with a warning. He parked his car right outside the Watergate building.

(10) The burglars then met up in room 214 before the break-in. Liddy gave each man between $200 and $800 in $100 bills with serial numbers close in sequence. McCord gave out six walkie-talkies. Two of these did not work (dead batteries).

(11) McCord taped the 6th, 8th and 9th floor stairwell doors and the garage level door. Later it was reported that the tape on the garage–level lock was gone. Hunt argued that a guard must have done this and suggested the operation should be aborted. Liddy and McCord argued that the operation must continue. McCord then went back an re-taped the garage-level door. Later the police pointed out that there was no need to tape the door as it opened from that side without a key. The tape served only as a sign to the police that there had been a break-in.

(12) McCord later claimed that after the break-in he removed the tape on all the doors. This was not true and soon after midnight the security guard, Frank Wills, discovered that several doors had been taped to stay unlocked. He told his superior about this but it was not until 1.47 a.m. that he notified the police.

(13) The burglars heard footsteps coming up the stairwell. Bernard Barker turned off the walkie-talkie (it was making a slight noise). Alfred Baldwin was watching events from his hotel room. When he saw the police walking up the stairwell steps he radioed a warning. However, as the walkie-talkie was turned off, the burglars remained unaware of the arrival of the police.

(14) When arrested Bernard Barker had his hotel key in his pocket (314). This enabled the police to find traceable material in Barker’s hotel room.

(15) When Hunt and Liddy realised that the burglars had been arrested, they attempted to remove traceable material from their hotel room (214). However, they left a briefcase containing $4,600. The money was in hundred dollar bills in sequential serial numbers that linked to the money found on the Watergate burglars.

(16) When Hunt arrived at Baldwin’s hotel room he made a phone call to Douglas Caddy, a lawyer who had worked with him at Mullen Company (a CIA front organization). Baldwin heard him discussing money, bail and bonds.

(17) Hunt told Baldwin to load McCord’s van with the listening post equipment and the Gemstone file and drive it to McCord’s house in Rockville. Surprisingly, the FBI did not order a search of McCord’s home and so they did not discover the contents of the van.

(18) It was vitally important to get McCord’s release from prison before it was discovered his links with the CIA. However, Hunt or Liddy made no attempt to contact people like Mitchell who could have organized this via Robert Mardian or Richard Kleindienst. Hunt later blamed Liddy for this as he assumed he would have phoned the White House or the Justice Department who would in turn have contacted the D.C. police chief in order to get the men released.

(19) Hunt went to his White House office where he placed a collection of incriminating materials (McCord’s electronic gear, address books, notebooks, etc.) in his safe. The safe also contained a revolver and documents on Daniel Ellsberg, Edward Kennedy and State Department memos. Hunt once again phoned Caddy from his office.

(20) Liddy eventually contacts Magruder via the White House switchboard. This was later used to link Liddy and Magruder to the break-in.

(21) Later that day Jeb Magruder told Hugh Sloan, the FCRP treasurer, that: “Our boys got caught last night. It was my mistake and I used someone from here, something I told them I’d never do.”

(22) Police took an address book from Bernard Barker. It contained the notation “WH HH” and Howard Hunt’s telephone number.

(23) Police took an address book from Eugenio Martinez. It contained the notation “H. Hunt WH” and Howard Hunt’s telephone number. He also had cheque for $6.36 signed by E. Howard Hunt.

(24) Alfred Baldwin told his story to a lawyer called John Cassidento, a strong supporter of the Democratic Party. He did not tell the authorities but did pass this information onto Larry O’Brien. The Democrats now knew that people like E. Howard Hunt and Gordon Liddy were involved in the Watergate break-in.

Several individuals seem to have made a lot of mistakes. The biggest offenders were Hunt (8), McCord (7), Liddy (6), Barker (6) and Baldwin (3). McCord’s mistakes were the most serious. He was also the one who first confessed to what had taken place at Watergate.