Tony Ulasewicz

Anthony Ulasewicz, the son of Polish immigrants, was born in New York on 14th December, 1918. His father was a tailor in the garment industry. His mother, who was a janitor, died of viral pneumonia, when he was a boy.

Ulasewicz attended Stanislaus Parochial School and Peter Stuyvesant Public High School. In 1937 Ulasewicz joined the Army National Guard. He was stationed at the 168th Street Armory, in Manhattan.

On 17th February, 1943, Ulasewicz joined the New York City Police Department. He started off as a patrolman in Harlem's Twenty-Fifth Precinct. Later he served in the United States Army during the Second World War.

In 1949 Ulasewicz joined the NYPD's Bureau of Special Service and Investigation (BOSSI). His assignments included escorting and guarding the security of world leaders and their families. People who Ulasewicz protected included Paul Robeson, Dwight Eisenhower, Nikita Khrushchev, John F. Kennedy, Rafael Trujillo and Fulgencio Batista.

Ulasewicz's intelligence work included the investigating the kidnapping and murder of Jesus de Galindez, the academic who had written a book critical of the Trujillo's military dictatorship. Ulasewicz discovered the CIA had stolen documents belonging to Galindez soon after he went missing. Ulasewicz decided to back-off when he discovered that the CIA was probably involved in his abduction. However, J. Edgar Hoover insisted on a full investigation. Galindez had been a FBI undercover agent (codename “Rojas”) who had been providing important information to Hoover.

Recruited to the FBI in June, 1944, Galindez had originally been asked to discover information about Spaniards who had migrated to the Dominican Republic after the Spanish Civil War. Galindez role was to discover if any of these men were “communists” and who might get involved in the campaign to bring democracy to the Dominican Republic.

Galindez also provided Hoover with information on the rebels in Cuba. This included information that Fidel Castro was a communist agent. This was important news at the time because Hoover was aware that the CIA were at the time helping Castro in his struggle with Fulgencio Batista.

Ulasewicz eventually traced the two men who flew the drugged Galindez to Dominica. Both these pilots, Gerald Murphy and Octavia de la Maza were murdered soon after this had taken place. So also was Ana Gloria Viera (Maza’s girlfriend) who was also on board the plane that night. Murphy, a young American pilot, had the contact details of man called John Frank in his possession when his body was found. Frank had been working with Robert Maheu. At the time it was believed that Frank and Maheu were involved in some CIA operation. It included a deal that involved the future of Batista’s gambling empire in Cuba and the training of CIA operatives in the Dominican Republic.

Soon after being elected to office, President Richard Nixon decided that the White House should establish an in-house investigative capability that could be used to obtain sensitive political information. Jack Caulfield, a former member of the New York City Police Department, was hired by H. R. Haldeman In May 1968.

In March, 1969, John Ehrlichman had a meeting with Caulfield and asked him to set up a private security entity in Washington to provide investigative support for the White House. Soon afterwards Caulfield employed Ulasewicz to carry out this work. Ulasewicz met Ehrlichman at the VIP lounge at the American Airlines Terminal of New York's La Guardia Airport. Ehrlichman agreed to pay Ulasewicz $22,000 a year plus expenses in return for "discreet investigations done on certain political figures.

Ulasewicz then had a meeting with Herbert W. Kalmbach who paid him out of surplus funds from the 1968 presidential election campaign. All told, Kalmbach paid more than $130,000 for the Caulfield-Ulasewicz operation. In an attempt to hide his activities Ulasewicz was told to apply for an American Express card in the name of Edward T. Stanley.

Over the next three years Ulasewicz travelled to 23 states gathering information about Nixon's political opponents. This included people such as Edward Kennedy, Edmund Muskie, Larry O'Brien, Howard Hughes and Jack Anderson.

Ulasewicz's first task was to investigate the relationship between Bobby Baker and Hubert Humphrey. Nixon had received information from Rose Mary Woods that the two men were involved in the Minnesota-based Mortgage Guarantee & Insurance Company.

On 19th July, 1969, Ulasewicz received a phone call from Jack Caulfield: "Get out to Martha's Vineyard as fast as you can, Tony. Kennedy's car ran off a bridge last night. There was a girl in it. She's dead." This phone call took place less than two hours after the body of Mary Jo Kopechne, the former secretary of Robert Kennedy, had been found in a car that Caulfield suspected Edward Kennedy had been driving.

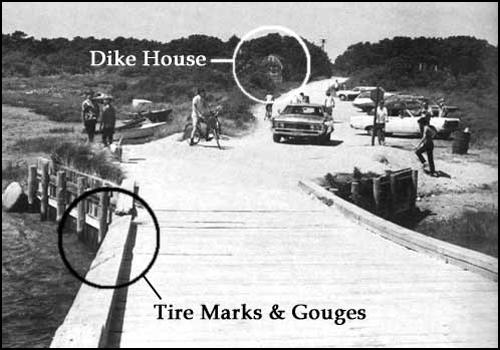

Ulasewicz was one of the first to arrive in Chappaquiddick after the tragedy. In several cases he was able to interview several key witnesses. This included Sylvia Malm who was staying in Dike House at the time. Dike House was only 150 yards from the scene of the accident. Malm told Ulasewicz that she was reading in bed on the night of the accident. She remained awake until midnight but no one knocked on her door.

Ulasewicz also discovered that the request for an autopsy by Edmund Dinis, the District Attorney of Suffolk County, had been denied. Dinis was told that the body had already been sent to Kopechne's family. This was untrue, the body was still in Edgartown. Ulasewicz also interviewed John Farrar, the scuba diver who pulled Mary Jo Kopechne out of Kennedy's car. Farrar told Ulasewicz that the evidence he saw suggested that she had been trapped alive for several hours inside Kennedy's car.

He also discovered that the "records of Edward Kennedy's telephone calls in the hours after the accident at Chappaquiddict were withheld by the telephone company from an inquest into the death of Mary Jo Kopechne without the knowledge of the Assistant District Attorney who asked for them". He leaked this information to various newspapers but it was only taken up by the Union Leader of Manchester, New Hampshire. It was not until 12th March, 1980, that the New York Times published the story.

Ulasewicz received orders from John Ehrlichman, H. R. Haldeman and Charles Colson. He also worked closely with Rose Mary Woods and her brother, Joseph Woods. In December 1971 appointed former New York City police detective, Anthony LaRocco, to help Ulasewicz in his work.

On 17th September, 1971, John Dean and Jeb Magruder arranged with Jack Caulfield to establish a new private security firm. Caulfield was told that Ulasewicz and his associates would be required to carry out "surveillance of Democratic primaries, convention, meetings, etc.," and collecting "derogatory information, investigative capability, worldwide." Ulasewicz was told that this was an "extreme clandestine" operation. Given the name Operation Sandwedge, its main purpose was to carry out illegal electronic surveillance on the political opponents of Richard Nixon.

Ulasewicz was given $50,000 by Herbert W. Kalmbach to carry out this work during the 1972 presidential election campaign. Charles Colson suggested to Jack Caulfield that his men fire-bomb the Brookings Institute (a left-wing public policy group involved in studying government policy in Vietnam). Caulfield sent Ulasewicz to investigate the location of offices, security provisions, etc. According to Caulfield the fire-bomb plan was eventually "squelched" by John Dean.

On 27th October, 1972, Time Magazine published an article claiming that it had obtained information from FBI files that Dwight Chaplin had hired Donald Segretti to disrupt the Democratic campaign. The following month Carl Bernstein interviewed Segretti who admitted that E. Howard Hunt and Gordon Liddy were behind the dirty tricks campaign against the Democratic Party.

In December 1972, Anthony Ulasewicz had a meeting with J. Timothy Gratz who provided information that Donald Segretti (Don Simmons) had tried to recruit him to a dirty tricks campaign against Edmund Muskie and George McGovern.

When the Watergate break-in took place John Ehrlichman immediately assumed that Ulasewicz had been involved. Ulasewicz found the whole case very confusing. As he wrote later: "as the burglars didn't even know enough to tape the door jam up and down instead of from front to back which exposed it, I assumed the break-in at the DNC had been orchestrated with an army in order to cover the real purpose of the effort ".

Herbert W. Kalmbach and John Dean decided that Ulasewicz was the best man to deliver the "hush money". He admitted later that he gave Dorothy Hunt a total of $154,000. This was to be passed on to Gordon Liddy, E. Howard Hunt, Frank Sturgis, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker and James W. McCord.

When Jack Caulfield gave evidence to Sam Ervin and the Senate Watergate Committee, he admitted the role that he and Ulasewicz had played in Operation Sandwedge. Ulasewicz appeared before the committee on 23rd May, 1973. To his surprise, the senators did not ask any specific questions of his work for Richard Nixon. Instead they concentrated on how he delivered the money to the Watergate burglars.

In June 1974, Alexander Haig began a classified investigation to determine whether Nixon had received cash contributions from leaders of Southeast Asia and the Far East. Ulasewicz was interviewed about the possibility that he had collected some of this money from people in Vietnam.

Although he admitted to the "crime of obstructing a criminal investigation" he was never charged with this offence. He insisted that he had done no deal with the prosecutors. However, in May, 1975, he was indicted for failing to include on his tax returns the money he had received from Herbert W. Kalmbach. He was found guilty in February, 1977, and sentenced to one year's unsupervised probation.

In 1977 Ulasewicz had a meeting with Richard Nixon at his home at San Clemente. They had a "heart to heart" talk. Nixon asked him: "What was it, Tony? What did it? What do you think caused Watergate? Ulasewicz replied: "You had a lot of guys around you who were trying to protect their own future at your expense." He admitted in his autobiography, The President's Private Eye (1990) that he did not tell him the full truth.

Anthony Ulasewicz died in 1997.

Primary Sources

(1) (1)The Senate Watergate Report (1974)

Caulfield also talked with Ulasewicz about forming a private security business. Ulasewicz's assignments had declined as 1971 progressed, and Caulfield had often talked with Ulasewicz about entering private business when Caulfield left the government. Caulfield envisioned Ulasewicz as head of the New York office of the new corporation, with primary responsibilities for offensive intelligence-gathering. Ulasewicz subsequently rented an apartment at 321 East 48th Street (Apartment 11-C), New York City, that could be used as an office for the private detective agency.

In the late summer of 1971, Caulfield met with Acree, Barth, and Joe Woods for about two hours at his home to discuss the proposal .

Following the meeting, Caulfield told Dean of the group's plans, and Dean asked Caulfield to commit the proposal to writing. Caulfield then drafted the memorandum entitled Operation "Sandwedge". The document called for an offensive intelligence gathering operation which would be clandestinely based in New York and would be able to infiltrate campaign organizations and headquarters with "undercover personnel:" The offensive capability would also include a "Black bag" capability, "surveillance of Democratic primaries, convention, meetings, etc.," and "derogatory information investigative -capability, worldwide."

In addition, the memorandum outlined an operating cover for the entity. The new corporation would hire itself out to large Republican corporations, whose fees would finance the clandestine and offensive capability envisioned in the memorandum. Caulfield emphasized the clandestine nature of the operation: "The offensive involvement outlined above would be supported, supervised and programmed by the principals, but completely disassociated (separate foolproof financing) from the corporate structure and located in New York in extreme clandestine fashion."

Caulfield noted in the memorandum that Ulasewicz would head the clandestine operation in New York, claiming that "his expertise in this area was considered the model for police - departments throughout the nation - and the results certainly proved it." Woods would be in charge of the midwestern office of the new corporation, heading covert efforts and acting as liaison to retired FBI agents "for discreet investigative support" from the FBI. Mike Acree would provide "IRS information input" and other financial investigations that would help support the New York City operation.

However, earlier in his memorandum, on page two, Caulfield discussed a former FBI agent who was known as a "black bag" specialist while at the FBI. Caulfield acknowledged that the term "black bag specialist," means an individual who specialized in breaking and entering for the purpose of, placing electronic surveillance. In addition, Caulfield noted that the term "bag job" in the intelligence community meant a burglary for the placement of electronic surveillance. Thus it appears that the capability to which Caulfield was referring inn his "Sandwedge Proposal" was one of surreptitious breaking and entering for the purpose of placing electronic surveillance, quite similar in nature to the Gemstone Operation which ultimately evolved.

(2) (2)Tony Ulasewicz, The President's Private Eye (1990)

Caulfield became Ehrlichman's contact with BOSSI, and through Ehrlichman, Caulfield met H. R. Haldeman, who would become Nixon's chief of staff after he was elected President. Both Ehrlichman and Haldeman were impressed with BOSSI's thoroughness in handling security, and at Ehrlichman's prodding, Haldeman persuaded the Police Commissioner to let Caulfield become head of Nixon's campaign security detail. Caulfield's assignment was classified as detached departmental service. Almost immediately after his appointment, Caulfield called to ask me to join Nixon's campaign train, but I turned him down. The job simply held no challenge for me. In my mind a campaign security assignment would mean nothing more than a lot of glitz and tinsel draped over a lot of travel, talk, and parties and too little sleep.

In March 1969, after Nixon had won and taken office, Caulfield again approached me about a possible assignment. It wasn't going to be what I thought, Caulfield said; it would be so different in fact that he couldn't talk about it over the phone. This time I was a bit more receptive, having in the last few weeks begun to think about retiring. In 1969, at age fifty-one, I was only seven years away from retirement on a full police pension, but setting myself up in business as a private investigator had begun to interest me. An affiliation with the White House would surely benefit the future of my own operation, and so I was ready to hear Caulfield out. We met at the Hofbrau, a bar and restaurant near 42nd Street which had long been a hangout for both New York's cops and reporters for the Daily News.

I hadn't seen Caulfield in over a year, and in an instant I could see that he had already become a tout for all the power that makes Washington move. He was just bursting with his news that he had found the Yellow Brick Road and was going to make a million bucks as a lobbyist when he finished working for Nixon. "The lobbyists in Washington run the whole show," he said. But I wasn't interested in his ambitions; all I wanted to know was what was so hush-hush that he couldn't tell me about it over the phone.

Over a few drinks, Caulfield outlined the big secret. He said the White House wanted to set up its own investigative resource which would be quite separate from the FBI, CIA, or Secret Service.

(3) (3)Tony Ulasewicz (with Stuart A. McKeever), The President's Private Eye (1990)

I wanted to know what happened in the car between Kennedy and Kopechne after they left the party on Chappaquiddick and before it flipped over the bridge. Only Kennedy could answer that and, up until now, he hadn't and probably never would.

What did it all mean? I thought about Kennedy swimming the channel back to Edgartown, not going to the police station to report the accident, and then, almost mysteriously, appearing fresh as a daisy; he was dressed and clean shaven as if nothing, nothing! had ever happened. How does a man live with himself if he doesn't know whether someone he was just with is alive or dead? How do you explain the fact he showed no feelings until after he was told the body was found and only then, according to witnesses, did Kennedy appear to realize what happened. Then my thoughts shifted to all those hours Kopechne was in the car, to her rigid, statue-like body, her claw-like hands, her terror, and then no autopsy to learn if water was in her lungs. No medical examiner in the world worth his salt would have signed off as quickly as Dr. Mills.

On Monday, January 5, 1970, the inquest into the death of Mary Jo Kopechne began in the Edgartown District Court for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. I was there, along with many others, shivering in the cold outside the courthouse. Not only was the public barred, but also the press. The journey to the inquest was my fifth trip to Edgartown. For four days, I stood in the cold outside the courthouse. It looked like the World Series had come to town: reporters, law students in recess, camera crews, traveling court buffs, Edgartown residents, and myself, among others, stood cloaked with the same motive-to find a way to get inside. But there wasn't any. Every available electronic security gadget was in place to make sure no one got a piece of the evidential pie until Judge Boyle released the slices.

While waiting for the inquest to end, I mentally speculated whether Kennedy's own phone calls had also been taken out-eliminated by his contact within the phone company or, inadvertently, by the White House connection who might have caused an overlapping obliteration of everyone's records. The phone company could never deny that there were once records of my calls to the White House. Not only did I make them, but they were also paid for with funds provided by Herb Kalmbach, the President's personal attorney.

(4) Tony Ulasewicz (with Stuart A. McKeever), The President's Private Eye (1990)

The Union Leader's "Ace" Egan and I had agreed that the next time we met, it would be on his turf. In early August, we met in the lobby of the Howard Johnson Motel in Manchester, New Hampshire. Egan had picked this spot because, he said, nobody would bother us there. Having arrived before Egan, I watched him approach the lobby accompanied by two other men. From a distance, I thought that one of the men might have been Loeb himself. However, the two men waited outside the lobby and I never got a good look at their faces. As Egan came toward me I wondered how far my con job of him could travel. I was still Ed Ferguson, investigative reporter and had nothing to give him except a repeat of what he already knew-namely, the numbers and location of the public phones on Chappaquiddick. Egan looked as confident and cocky as any reporter I had ever met. He was on a mission to prove something, and that apparently neutralized any doubt on his part as to who I was or what I could deliver.

"Here's the list," Egan said as he handed me three folded sheets of paper. The perforation marks on the edges of the paper reminded me of the teletype paper I used to see in the Twenty-fifth Precinct during my years in Harlem. The records were authentic all right. I had seen plenty of phone records in my time as a detective and knew what to look for. There were handwritten notations of the names of some of those who had received the calls, the time the calls were made, and the listed owners of the phone numbers. There were also notations of "Ch" and "Pot" in the margin. Egan said they were abbreviations for the Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Companies, respectively, which had issued a credit card in Kennedy's name. The list showed that phone calls had been made from a variety of points on Martha's Vineyard which indicated that more than one person had been using Kennedy's credit card during the night.

What bothered Egan the most was trying to match a 21-minute call that was made before midnight to the time Kennedy claimed he arrived back at the cottage after the accident. This call was traced to a phone number at the cottage and was made to the Kennedy compound in Hyannis. If Kennedy showed up before midnight but didn't tell anyone what had happened except Gargan and Markham, both of whom then went back to the bridge with Kennedy, then whoever made the call, if you believed Kennedy's statement, couldn't have known about the accident. Kennedy had already said on national television that nobody at the cottage knew about the accident except Gargan and Markham. If someone else knew and got on the phone as soon as Kennedy returned to the cottage, they were keeping quiet about it. Egan told me that he didn't know whether the phone that was used was the one I saw in the studio behind the cottage or one that was in the cottage itself. While it was possible that someone just wanted to make a social call around midnight and charge it to Kennedy's credit card, the timing was all wrong to accept that proposition.

To make matters worse, Egan said that when he confronted the Police Chief, Dominick Arena, at Police Headquarters about the phone calls, Arena said he knew all about the calls from the cottage and the Inn. "Which Inn?," I asked Egan. "The Shiretown," Egan answered, "where Kennedy stayed." Checking the list I saw that during the night several calls were made from a pay phone at the Inn and charged to Kennedy's credit card. The timing of these calls fit the period Kennedy was at the Inn after he swam back to Edgartown from the Chappaquiddick ferry dock. "What's, Arena doing about the calls,?" I asked Egan. "Nothing," he answered. "As far as he's concerned the case is closed." I wondered how Arena was going to deal with the calls when the coroner's inquest was held. Phone records were going to be subpoenaed and Arena was going to look like a fool for not questioning everyone who attended the Kennedy party about the calls.

I couldn't give myself away and tell Egan what I would have done with these phone records if I had had the chance, but if I did, I would have stuck everybody in a room and called them in one by one and kept rotating them in and out until somebody broke. If no one owned up to making any of the calls, then Ted Kennedy had himself one monumental problem. He had lied to the nation on television because the phone calls were certainly made, and only he could explain them away. If someone did admit to the calls, then Kennedy was still in trouble because he said he didn't call or tell anybody about the accident (except Gargan and Markham) until the morning after. In any event, none of the calls that were made that night sought help for Mary Jo Kopechne.

The calls on the list Egan showed me continued throughout the night. Some of them were made from the phones whose numbers I had recorded and given to Egan. I didn't ask to have a copy of the list because I really didn't have anything more to give Egan in return. But Egan didn't press me. His greatest need was reassurance that someone else had information that conformed with his; that when likely denials surfaced from the phone company and the Kennedy group, there was a force behind him to take on the challenge. Little did he know that the Nixon White House would be behind him all the way. "I've still got four or five more days work on this story," Egan said, "and then I'll let it fly."

On August 13, the Union Leader published Egan's story about the phone calls he and I were certain Kennedy or his friends had made between the time of the accident and dawn. The number of these calls gave the lie to Kennedy's claim that he experienced a period of absolute silence after the accident before his mind woke up to report it. Egan's story began: "Although U.S. Senator Edward M. Kennedy claimed to be in `a state of shock' after the traffic accident which took the life of a pretty female companion, he nevertheless had the mental fortitude to make a total of 17 telephone calls in the hours succeeding the accident."

Sure enough, within a few days of the Union Leader's publication of Egan's story, the New England Telephone Company denied the existence of the records. It didn't surprise me a bit, for that was their job. Egan confirmed his story in a follow-up article by disclosing his source for the records as James T. Gilmartin, a friend of Egan's who was an attorney and real estate broker with an office at 147 East 230th Street in the Bronx. Gilmartin had the right connection inside the phone company. Egan also wrote that he had a conversation with a Richard E. McLaughlin of the Massachusetts Registry of Motor Vehicles in Boston who told Egan that Kennedy's license wasn't wet and showed no signs of being immersed in water. McLaughlin denied ever speaking to Egan. After threatening a lawsuit and filing a complaint with the Massachusetts Public Service Commission, the Union Leader published a story which printed, in full, a letter from the New England Telephone Company confirming Egan's story about the calls to and from McLaughlin. Operator toll-tickets, as they are called, proved Egan's allegations.

For whatever reason, Egan's story about the phone calls never took off in the press. While his scoop carried here and there, the media didn't pick up the story and run with it as a challenge to Kennedy's claim that he never contacted anyone until the morning after the accident. That in itself wasn't surprising either. Since everyone knew that Loeb and the Union Leader were out to tar and feather any Kennedy they could find, Egan's story had less impact than it would have had coming from a less biased paper. Regardless of the story about the phone calls, reporters and journalists around the world were not buying the Kennedy version of what happened. Staff members of the Republican National Committee were kept busy clipping and pasting together every newspaper article and editorial that broke into print. The White House wanted a record of the attack on Kennedy's credibility to use if Kennedy ever sought the Presidency. A scrapbook of the articles and editorials was put together and given the title: "At an Appropriate Time."

On Wednesday, March 12, 1980, The New York Times finally published a lengthy front-page article headlined "Gaps Found in Chappaquiddick Phone Data." The story confirmed what Egan and I had known many years before that there had been a coverup.

"Records of Senator Edward M. Kennedy's telephone calls, " The New York Times article began, "in the hours after the accident at Chappaquiddick were withheld by the telephone company from an inquest into the death of Mary Jo Kopechne without the knowledge of the Assistant District Attorney who asked for them." The first call on the list the phone company produced at the inquest wasn't made until almost 11 o'clock in the morning. That a coverup of the calls I saw had been set in motion was confirmed again when I read that a pilot called by a Kennedy associate had flown over Chappaquiddick while Kennedy's car was still in the water. The Times story claimed that the Kennedy associate who made the call had been on Nantucket, not Martha's Vineyard. Someone had to have called him first before he told the pilot to start up the engines of his plane. I regretted not having had the second chance to check the identification numbers of the plane I saw parked behind the Katama Shores Motel and learn the owner and when that plane had landed there. The Kopechne family deserves a boatload of answers to the questions left unanswered. If they want the case reopened, I sure wouldn't blame them.

(5) Tony Ulasewicz (with Stuart A. McKeever), The President's Private Eye (1990)

I spent the entire night of July 19 on Chappaquiddick, taking periodic cat naps in my car and moving it every so often so that some snoop wouldn't knock on my window or write down my license plate number. I had charged the car rental to my own American Express card rather than the one issued for my alias, Ed Stanley, because Stanley was my tie-in to the White House. I did have to use the telephone credit card issued to Stanley, however, because I hadn't had the time to obtain one in my own name. I resolved that after I finished this assignment, Stanley's name and the list of his calls would be eliminated from telephone company records. That was an assignment I intended to give to Caulfield. Using my own credit card on Martha's Vineyard or Chappaquiddick wouldn't link me to anyone. I also had a practical reason for charging the rental car to my own name: I had to account for my travel and expenses. On every investigation I eventually did for the White House, I always charged one item to my own credit card in order to prove I had been where I said I was in the event anyone in the White House ever raised any question about my expenses. I kept exact records.

As dawn broke over Chappaquiddick, I returned to Dike Bridge, confirming my thoughts of the night before and planning my next move. I had to act quickly. The media heavyweights would soon arrive from their coverage of the historic trip to the moon, and some of them would, of course, be from the New York press corps. I didn't need to hear a "Hey, Tony" or have my shoulder tapped by an old acquaintance.

I waited on Chappaquiddick until a decent hour and then went to "Dike Cottage." As I stood waiting for the door of the cottage to open, I became a man named Ferguson, a fictional investigative reporter for a doubly fictional feature writer's association I had made up. Ferguson wasn't exactly Clark Kent from the Daily Planet, but he wasn't a bad guy either. Answering the door of the cottage was Mrs. Pierre Malm. Dike Cottage was her summer home, she said, her permanent residence being in Lebanon, Pennsylvania. It was to her door that the two boys who spotted Kennedy's car had come to report their sighting. Mrs. Malm told me she was upstairs reading in bed on the night of the accident when she heard a car pass their cottage. The car, she said, was traveling rather fast as it headed for the bridge. She didn't hear it return. She didn't hear it hit anything or go crashing into the water. She stopped reading for a short while as she listened for further sounds. Hearing none, she continued reading until midnight, then put out the light and went to sleep. She told me that her two dogs would have barked and awakened her if anyone had come near the cottage. Nobody did. Only the two youngsters who came the next morning to tell her what they found.

Afterward, I headed back to Edgartown with a shopping list of questions in my head. Although I desperately wanted to go to sleep, I wanted to learn the official cause of death as well as the results of the autopsy I expected had been performed on the girl. So I went to the obvious place: the Edgartown Funeral Home. The first question I asked was who had been called to the scene to examine the body after it had been pulled out of the car. The owner and director of the funeral home, Eugene Frieh, told me that he had been called together with Dr. Donald R. Mills, an Associate Medical Examiner for Suffolk County. Mills had examined the body at the bridge. According to Frieh, Mills estimated that Mary Jo Kopechne had been dead for approximately six hours before being pulled out of the car. But the radio reports-if you could believe them-said that her body had been in the car at least nine hours before being brought to the surface. That left three hours of possible life to account for. I wondered if there was an air pocket in the car after it sank in the pond. I then asked Frieh about the autopsy.

"There wasn't any," Frieh said.

"No autopsy?," I asked in astonishment.

"No," Frieh answered. "They said it wasn't necessary."

"Who said it wasn't necessary?"

"Dr. Mills. He said she drowned."

"What kind of examination did he give her?"

"He checked her with his stethoscope, pushed against her chest and turned her over."

"What happened when he pushed her chest?"

"Mills said there was a lot of water in her. I didn't see much water. I saw a lot of foam around her nose and mouth." "How long did the examination take?"

"Just a few minutes."

"That's all?"

"That's all."

I was dumbstruck that an autopsy hadn't been demanded. Where I come from, an autopsy would have been standard operating procedure. During the years I was assigned to Harlem's Twenty- fifth Precinct, the currents of the Harlem River frequently became the escort for bodies that floated up the river with other flotsam and jetsam and then got wedged up against the base of the Triborough Bridge. When a body was pulled out of the water, the amount of fluid pouring from it governed the intensity and the time the "brains" in the detective squad spent investigating the cause of death. The less saturation of the tissues, the more intense the investigation. Ordering an autopsy would have been automatic. As I talked to the Edgartown funeral director I also knew that the presence of foam around the nose and mouth was an indicator of oxygen starvation, not drowning. If the radio reports issued about the time of the accident were accurate and Mills' estimate of the time of death was on target, then there was a good chance that the girl had been alive in Kennedy's car for quite awhile after his car hit the water. For public consumption, Mills was quoted as saying, "The body was rigid as a statue, the teeth were gritted, there was froth around the nose, and the hands were in a claw-like position."

During my discussion with Frieh, I noticed that he kept twisting and turning his body to point out a casket as he talked. I didn't need a road map to tell me that it was the girl's casket. Frieh also told me that on Saturday afternoon, after the body had been placed in his custody and delivered to his funeral home, someone-Frieh couldn't remember his name-identifying himself as a Kennedy staff member said he was there to complete arrangements to fly the girl's body back home to Pennsylvania.

(6) Tony Ulasewicz (with Stuart A. McKeever), The President's Private Eye (1990)

I remained in the area until July 23. I had found a place to stay on Martha's Vineyard between Edgartown and Gay Head so I wouldn't have ' to run back and forth to Woods Hole. Before packing up and heading for home, I went to see John Farrar, the scuba diver who pulled Mary Jo Kopechne out of Kennedy's car. When I met him in his dive and tackle shop in Edgartown, he seemed anxious to talk. He gave me the feeling that he didn't think anyone except the press was really listening to what he had to say; that what he saw was starting to become a nightmare. When he entered the submerged vehicle, Farrar said, he saw the girl's head cocked back, her face pressed into the foot well, her hands gripping the front edge of the back seat, her body shaped for the struggle to get a last gasp of air. It appeared to him, Farrar said, that Kopechne had been trapped alive for several hours inside Kennedy's car.

(7) (7)The Senate Watergate Report (1974)

Jeb Magruder. Generally, the complaints were that there was an individual in the field who was causing serious problems for the Committee to Re-Elect the President. Such a complaint was sent from J. Tim Gratz of Madison, Wisconsin, to Carl Rove, President-elect of the College Republicans. This complaint was eventually assigned to Anthony Ulasewicz who flew out to Wisconsin to investigate this mysterious individual. Ulasewicz did not succeed in tracking down Segretti, but while he was out in Wisconsin, he received a call from Jack Caulfield who informed him that Segretti worked for CRP.

(8) (8)J. Timothy Gratz, statement made to Tony Ulasewicz(December, 1972)

I received a telephone call at my apartment on Saturday morning, December 18th, 1972, from a man who identified himself as Mr Don Simmons. He said he wanted to find a young person in Madison to do work for the reelection of the President, for about ten to fifteen hours per month, and wanted to put this individual on a retainer basis. He said the work involved opposition research, etc.

He said he was from a political consultant firm in New York. He said he received my name from Randy Knox. We set up a meeting in the Park Motor Inn Lounge for that afternoon.

Simmons said he was interested in running a "negative campaign" in Wisconsin. He explained that the purpose of the campaign was to create as much bitterness and disunity within the Democrat primary as possible. He suggested doing things such as planting questions in student audiences before which the Democrat candidates were working, getting students to picket the Democrat candidates, e.g. a black student to picket Muskie regarding his remark on a black V.P. candidate, etc. He also said he was interested in planting spies in the Democrat candidate's offices. He said that he wanted to concentrate on Muskie, and give second priority to McGovern.

Simmons said he wanted to pay someone $100.00 per month, plus expenses, to co-ordinate these projects. He also said he was willing to pay a salary of up to $50.00 per month to a person we could plant in Muskie headquarters.

I asked him if he was working for the CCREP or the RNC. He replied he was working on his own, with his own money. (He implied that he was saying this because he did not want anyone to be able to trace his activities to the Nixon campaign or the Party officially.) I asked him how I could establish his credentials, and he was, frankly, evasive, although I got the impression that he was implying this evasiveness was deliberate.

Although the whole incident seemed strange, I tentatively agreed to work on his project (as most of the ideas he suggested seemed like they were worth doing anyway). He gave me $50.00 in advance payment, and said he would call back in early January. He said I should concentrate initially on finding someone to plant in Muskie HQ. He said that we would communicate only by telephone, for security reasons.

Mr. Simmons registered at the Park Motor Inn on Dec 16, 1972, and checked out on Dec. 19th. He listed his home address as 1400 Olympic Avenue NW, Wash DC. He paid his bill in cash. He made approximately twelve local phone calls, and three long distance calls. One of the long distance calls was to Randy Knox' home in Fort Atkinson; one was to a Madison area (884 exchange) number, and one was to Peoria, Ill., 309-674-2143. (We are checking this number out through contacts in Illinois.)

(9) Tony Ulasewicz (with Stuart A. McKeever), The President's Private Eye (1990)

I was back in Washington at the request of J. Fred Buzhardt, the Special Counsel to the President appointed by Nixon after John Dean sold out and jumped ship in May 1973. At the time of his appointment, Buzhardt, a West Point classmate of Alexander Haig, Jr. (they graduated a year apart), was general counsel to the Department of Defense. I met with Buzhardt in John Dean's old office. Buzhardt said he wanted to know my real feelings about Nixon and where I was going to stand when the impeachment hearings began. He said he couldn't find anything in any White House files that was stamped with my initials or any memos I prepared, or any hint that I had incriminating evidence against the President in my pocket. Since I never signed or initialed anything, there was nothing there to find. But lurking in the background was an apparent feeling on the part of General Alexander Haig, who took over as White House Chief of Staff after Haldeman was booted out, that I knew something about Nixon supposedly getting part of a storehouse of cash that was left in Vietnam after the United States scrambled out of there. Although appointed by President Nixon himself, Haig, I began to think, was actually turning against the President in the final days before Nixon resigned.

In June 1974, Haig ordered the US. Army's Criminal Investigation: Command (CIC) to conduct a high-priority, classified investigation to determine whether Nixon had stuffed his pockets with cash contributions from leaders of Southeast Asia and the Far East. Haig even went so far as to ask for confirmation as to whether Nixon had connections with organized crime and had received payoffs from the Mafia. The State Department was contacted to see if I had a passport and, if so, whether I had used it to head for Vietnam. I didn't go, but if I had I certainly wouldn't have left a trace of how I got there and back. The Army CIC spent over a month trying to verify my nonexistent trip to Southeast Asia to pick up booty for the President. The investigation went nowhere, of course, but the timing of Haig's efforts to undercut the President meant that Haig - and perhaps others - wanted the President discredited long before this.

(10) Tony Ulasewicz (with Stuart A. McKeever), The President's Private Eye (1990)

At first, she (Dorothy Hunt) told me that she had lost her job over the Watergate scandal including her medical benefits. She said somebody had to take care of those. She started calculating everybody's needs and came up with a minimum figure of $3,000 a month, but as she didn't want to worry about a monthly delivery from the post man, it was better, she said, to get a big chunk up front to relieve the pressure on everybody. "So let's start with $10,000 or $15,000 apiece to get this thing off the ground," she said. She wanted the advance to cover five months of living expenses. She said Barker, Sturgis, Gonzales, and Martinez needed at least $14,000 apiece and that Barker needed another $10,000 for bail, $10,000 more under the table, and $3,000 for "other expenses." Twenty-five grand apiece were needed for Sturgis, Gonzales, and Martinez's attorneys. I told Mrs. Hunt to slow down. Now she was talking about $400,000 or maybe $450,000. That wasn't even close to the amount Dean had told Kalmbach to raise when they met in Lafayette Park.

When I told Mrs. Hunt that I had no room to negotiate and that it was pointless to present me with a shopping list of who needed what, she said people were starting to get desperate. They felt they were being abandoned. She added a new name when she told me that one of those who needed money was a guy named Liddy. He was involved in the break-in along with the "writer" but hadn't yet been charged with anything. That was news. Hunt's name had been found in an address book kept by one of the Watergate burglars. So had the name Colson. Now Mrs. Hunt was adding another name to the stew. I was a stranger to Mrs. Hunt, and yet she was telling me something that proved Hunt's connection to Colson in the White House. With Liddy in the picture the ring of involvement was widening, and I was learning more than I wanted to know. That was the first time I heard the name Liddy. The way she spoke about him, however, made me feel that she was looking for a way to deal him out of the game as quickly as she could. Liddy had to get some of the money, but just one payment and that was it, she said. Others had to be covered, lots of others whom she said were more important than Liddy. Living expenses were high for all these other people. Money was needed over and under the table. (I doubted many people in Washington really knew the difference.) She said that her husband and the other defendants wouldn't have to go to jail for very long because meetings were going on about that and about pardons and immunity.

The pressure that was building behind the scenes for the payment of increasingly large sums of money to those connected directly and indirectly to the Watergate break-in was turning this "one-shot deal" into a multiheaded tapeworm. It had some appetite, and to feed it, I had to meet Kalmbach on four different occasions to pick up additional sums of money. The first installment was the $75,000 I took out of the Statler Hilton in a laundry bag. The next dump in my lap was at the Regency Hotel in New York where I walked out with $40,000. The third course of the burglars' meal, $28,900, was again given to me at the Statler Hilton in Washington. Kalmbach gave me the last amount off the menu as we sat in a car outside the Airporter Motel at the Orange County Airport in California. It consisted of $75,000 in cash.

I delivered a total of $154,000 to Dorothy Hunt in four separate installments: $40,000, $43,000, $18,000 and $53,000. She was never satisfied with the amount of money I gave her. She never believed that 1 didn't have (and didn't want) the power to determine the breadth of financial support she said was necessary to keep things afloat. Neither Kalmbach nor I knew whether she was delivering what those involved were supposed to receive. She kept telling me about Barker's problems down south; that he needed a lot of cash to keep the lid on things in Miami. Again, she talked about Liddy as if she was trying to give him the shaft. She told me she was worried that Liddy's wife might crack under the strain. Mrs. Liddy was a school teacher and was frightened that she might lose her job if it was discovered that her husband was involved. Dorothy Hunt seemed to want to help Liddy's wife and yet get rid of her at the same time.

(11) Tony Ulasewicz (with Stuart A. McKeever), The President's Private Eye (1990)

Neither (Howard) Baker nor any other Senator asked me about the specifics of any of my investigations, although they must have known about them because (Terry) Lenzner had made a list of them for the committee. My financial records, including receipts for all my travel and lodging expenses, were also turned over to the committee. I was never asked about my trip to check out the offices of the DNC at the end of May, who asked me to go there, or who was behind that request. Caulfield's call to me the afternoon after the Watergate break-in was never explored, although John Dean was the man who had ordered the call to be made. I expected to be asked about my meeting with Dean when Caulfield was clearing out his office in the Executive Office Building. Again I wasn't. Dean, I concluded, was obviously being protected for star billing as a witness. No one asked me if I had any documents or White House memos about any of my investigations. While I had no intention of playing cute with anybody, I wasn't going to volunteer information unless I was asked for it. I wasn't asked about meeting "Mr. George" or hearing his off-the-wall intelligence plans for the campaign, or about Colson and the Brookings Institution, or about Simmons in Wisconsin. I didn't mind not being asked; I just didn't understand why I wasn't....

Baker asked me in general what my arrangement had been under the agreement I made with Ehrlichman in 1969, but when he asked me "of whom and about what" did I investigate, I didn't get a chance to open my mouth before Baker said, "Let me say this, Mr. Chairman. It is my understanding that Mr. Ulasewicz will once again return for further testimony in another category of testimony." I affirmed Baker's assumption and said, "That's correct." Baker then cut off the inquiry and said, "So we will abbreviate this inquiry at this point, with the full understanding that we can pursue that aspect of it later." Senator Weicker said. He wanted Baker to continue the line of questioning he started, but Baker ! responded that Committee Chairman, Senator Sam Ervin, whispered in his ear that "if we don't get on with this hearing, we'll still be here when the last trembling tones of Gabriel's trumpet fades into ultimate silence."

(12) Len Colodny and Robert Gettlin, Silent Coup: The Removal of Richard Nixon (1991)

If a senator made a speech against the president's policies in regard to Vietnam, Nixon would issue an order to Haldeman: "Put a twenty-four-hour surveillance on that bastard."

Why a surveillance? To obtain deleterious information that could be used against the senator. Nixon liked that sort of secret, intrigue related intelligence, and fostered an environment within the White House that put a premium on it. The president believed that the domestic information-gathering arms of the government - the FBI and other federal policing agencies - could not be counted on to undertake confidential assignments of the sort he had in mind. J. Edgar Hoover, Nixon believed, had files on everybody, but even though Hoover often cooperated with Nixon, the FBI director was reluctant to release any of those files to Nixon even after he became president, just as reluctant as Director Richard Helms would be in 1971 to release the CIA's Bay of Pigs files when Nixon instructed him to do so.

And so, just weeks after Nixon's inauguration, the president directed White House counsel John Ehrlichman to hire a private eye. "He wanted somebody who could do chores for him that a federal employee could not do," Ehrlichman says. "Nixon was demanding information on certain things that I couldn't get through government channels because it would have been questionable." What sort of investigations? "Of the Kennedys, for example," Ehrlichman wrote in Witness to Power.

Ehrlichman quickly found a candidate, a well-decorated, forty year-old Irish New York City cop, John J. Caulfield. Caulfield had been a member of the NYPD and its undercover unit, the Bureau of Special Services and Investigations (BOSSI). He had made cases against dissident and terrorist organizations, and BOSSI as a whole was known for its ability to penetrate and keep track of left-wing and black groups. One of the unit's jobs was to work closely with the Secret Service and guard political dignitaries and world leaders who frequently moved through the city. During the 1960 election, Caulfield had been assigned to the security detail of candidate Richard Nixon. He had befriended Nixon's personal secretary, Rose Mary Woods, and her brother Joe, the sheriff of Cook County, Illinois. In 1968, after leaving the New York City Police Department, Caulfield had served as a security man for the Nixon campaign.

But when Ehrlichman approached him in early 1969 and asked Caulfield to set up a private security firm to provide services for the Nixon White House, Caulfield declined, and instead suggested that he join Ehrlichman's staff and then, as a White House employee, supervise another man who would be hired solely as a private eye. Ehrlichman agreed, and when Caulfield arrived at the White House to start work in April 1969, he said he had the ideal candidate for presidential gumshoe, a BOSSI colleague, Anthony Ulasewicz.

In May 1969, Ehrlichman and Caulfield flew to New York and met Ulasewicz in the American Airlines VIP lounge at LaGuardia Airport. Ulasewicz was ten years older than Caulfield, just as streetwise, and even saltier, with a thick accent picked up from his youth on the Lower East Side and twenty-six years of pounding the pavement on his beats. He was told in the VIP lounge that he would operate under a veil of tight secrecy. He would receive orders only from Caulfield though he could assume that those came from Ehrlichman, who would, in turn, be acting on instructions from the president. Ulasewicz would keep no files and submit no written reports; he later wrote in his memoirs that Ehrlichman said to him, "You'll be allowed no mistakes. There will be no support for you whatsoever from the White House if you're exposed." Ulasewicz refused an offer of six months' work, and insisted on a full year, with the understanding that there would be no written contract, just a verbal guarantee. It was also agreed that to keep everything away from the White House, Ulasewicz would work through an outside attorney. In late June 1969, Caulfield directed Ulasewicz to come to Washington and meet a man named Herbert W. Kalmbach at the Madison Hotel. Kalmbach was Nixon's personal attorney in California, and he told Tony that he would be paid $22,000 a year, plus expenses, and that the checks would come from Kalmbach to Tony's home in New York. To avoid putting the private eye on the government payroll, Kalmbach was to pay him out of a war chest of unspent Nixon campaign funds. Ulasewicz requested and was promised credit cards in his own name and in that of a nom de guerre, Edward T Stanley. Shortly, he started on his first job for the Nixon White House. One day after Senator Edward M. Kennedy's car plunged off a bridge, killing a young woman, Tony Ulasewicz was at Chappaquiddick, Massachusetts, posing as a reporter, asking a lot of questions and taking photographs. He stayed a week, and phoned reports to Caulfield thrice daily.

Thereafter, he crisscrossed the country, investigating whatever the president or his subordinates thought proper targets for information such Democrats as George Wallace, Hubert Humphrey, Edmund Muskie, Vance Hartke, William Proxmire, and Carl Albert, Republican representatives John Ashbrook and Paul McCloskey, antiwar groups, entertainers, think tanks, reporters, even members of Nixon's own family.

(13) Len Colodny and Robert Gettlin, Silent Coup: The Removal of Richard Nixon (1991)

At first, Tony Ulasewicz's efforts to deliver money to people were a comedy of errors. Neither Douglas Caddy, the initial lawyer for the burglars, nor Paul O'Brien, CRP's lawyer, would take any of the money - they didn't want to be a part of the "script" - and Tony was only able to make one $25,000 payment to Hunt's attorney, William C. Bittman, before he, too, refused to take any further part in the payoffs. The proposed drops involved lockers in transportation centers, brown paper bags, staged rendezvous and fallback strategies, and a whole array of devices to avoid having the person being paid learn the true identity of the money carrier. Ulasewicz made so many telephone calls from public phone booths that he needed a hefty supply of nickels and dimes, so, as he later wrote, "To save my pants, avoid heavy bulging pockets, and an increasing dose of irritation, I bought myself a busman's money changer and hooked it on my belt." His deliveries hit their stride only after Kalmbach (acting on instructions from Dean) connected Tony to the "writer's wife," Dorothy Hunt.

Dean had a special reason to take care of Hunt, since Hunt had information on Dean's role in the DNC break-ins. To neutralize Hunt, Dean had already emptied Hunt's White House safe, given some of the sensitive files in it to Pat Gray, telling him that the files "clearly should not see the light of day," and had retained and concealed the Hermes notebooks that could link him to Hunt.

In the summer and fall of 1972, the deliveries to Dorothy Hunt went far beyond the money Tony had originally been given for the purpose of supplying the burglars' needs, and so Ulasewicz had to meet Kalmbach three more times to get more cash: $40,000 passed into Tony's care at the Regency Hotel in New York, $28,900 at the Statler-Hilton in Washington, and $75,000 at the Airporter Motel near the Orange County Airport in California. Mrs. Hunt told Tony that they had to get some money to Gordon Liddy, but "the way she spoke about him, however, made me feel that she was looking for a way to deal him out of the game as quickly as she could."

In short order, Ulasewicz delivered to Dorothy Hunt installments of $40,000, $43,000, $18,000 and $53,000, all in cash. These payments were ostensibly for the Cubans as well as for Hunt, but the Cubans saw very little of it. Two years later, after serving his prison sentence, Hunt admitted to Richard Ben-Veniste of the Special Prosecutor's

office that, as Ben-Veniste later wrote, "the cash received from CRP and the White House was a quid pro quo for silence." We find interesting an exchange that took place at the trial of the defendants on the cover-up charges. When Hunt was asked whether his demands were really blackmail, Hunt replied, "No, sir."

"What did you consider it, investment planning?" the cross-examining lawyer sarcastically asked.

"I considered it, if you will, in the tradition of a bill collector, attempting to get others who made a prior contract to live up to it."

Gordon Liddy believed he had made a contract of a different sort, and , had vowed to live up to it. On the twenty-eighth of June, in the CRP ' offices, he had taken the first action in his campaign of silence. He had refused to be interviewed by the FBI and had been summarily fired for refusing to cooperate. He arranged to go back to Poughkeepsie and work on some legal matters, but knew that sooner or later the Watergate trail would lead to him and he would be indicted and arrested. He believed he had made errors and was willing to take full responsibility for them; more importantly, he had determined never to allow the investigation to reach higher than himself. He had personally assured both Magruder and Dean that he would never talk, and made it the central point of his life to adhere to that promise. During this period between the burglary and his indictment, Liddy received a phone call suggesting that he was going to be paid for his "manuscript" in the form of money left in a locker at National Airport in Washington. Ulasewicz writes that he was insistent that money for Liddy "should go directly to him and not pass through the Hunts' hands. I did this not to keep Liddy quiet, but to keep him from getting screwed."

Liddy retrieved the money from the drop site and gave it all to his lawyer. Then he had a strange conversation with the Hunts, who said that if their "principals" wanted Liddy and Hunt out of the country, the Hunts would arrange for both families to be transported to Nicaragua, where they could live like kings under the protection of Hunt's friend Somoza. Later on in the summer, still before he was indicted, Liddy received $19,000 directly from Mrs. Hunt. She later told him that it really came from herself and Howard, not from their "principals," who didn't really care about Liddy. Liddy was furious but accepted this freeze-out with a stoic shrug, and went on remaining silent. Not until many years later did Liddy learn of the huge amounts that had been paid to Hunt as hush money.