Edward Kennedy

Edward (Ted) Kennedy, the youngest son of Joseph Patrick Kennedy and Rose Fitzgerald, was born in Brookline, Massachusetts, on 22nd February, 1932. His great grandfather, Patrick Kennedy, had emigrated from Ireland in 1849 and his grandfathers, Patrick Joseph Kennedy and John Francis Fitzgerald, were important political figures in Boston.

Kennedy later admitted that as the youngest child he was treated with the utmost indulgence by his mother and sisters. He commented in later life that it was like "having a whole army of mothers around me."

Kennedy's father was a highly successful businessman and supporter of the Democratic Party. In 1937 Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed him as ambassador to Great Britain. Ted lived in London during this period and by the end of the Second World War when he was 13, he had attended 10 different schools. His eldest brother, Joseph Patrick Kennedy, was killed in action in France in 1944.

In 1950 Kennedy won a place at Harvard University. He was an outstanding sportsman but had difficulty with his academic studies. As one of his biographers has pointed out: "Faced with a Spanish examination he was sure he would fail, Kennedy paid a more adept friend to take it for him. To the chagrin of his family, the plot was discovered and he was expelled, though the incident was covered up for more than a decade. With his exemption from military service now void, he was conscripted into the army from 1951 to 1953. The family appeared to regard his brief service career as a form of punishment and made no effort to ease his lot."

After two years in the US Army Kennedy was allowed to return to Harvard. He got a BA in government in 1956 but failed to qualify for its law school and after a period at the Hague Academy of International Law he enrolled at the University of Virginia. While a student he married the former model, Joan Bennett in 1958.

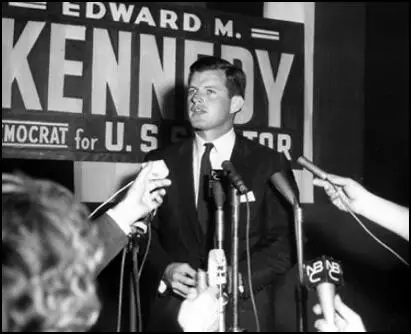

A member of the Democratic Party Kennedy became involved in politics and in 1958 managed the Senate election campain of his brother, John Fitzgerald Kennedy. He graduated as a bachelor of law in 1959 and was admitted to the Massachusetts bar.

In 1960 Edward Kennedy helped his brother, Robert Kennedy, manage John Kennedy's successful presidential campaign against Richard Nixon. However, as John M. Broder pointed out in the New York Times: "In 1960, when John Kennedy ran for president, Edward was assigned a relatively minor role, rustling up votes in Western states that usually voted Republican. He was so enthusiastic about his task that he rode a bronco at a Montana rodeo and daringly took a ski jump at a winter sports tournament in Wisconsin to impress a crowd. The episodes were evidence of a reckless streak that repeatedly threatened his life and career."

In 1962 Kennedy entered the Senate as a representative of Massachusetts.When his brother was assassinated in 1963 he flew to the family home in Hyannis Port where he had the task of telling his father, Joseph Patrick Kennedy, now frail and bedridden, the news. As Evan Thomas has pointed out: "When the president was assassinated in November 1963, it fell to Teddy to tell their stroke-ridden father. His clumsy wording suggests the pain. There's been a bad accident, Ted began. The president has been hurt very badly. As a matter of fact, he died. Then the son dropped to his knees and wept into the outstretched hands of his father."

On 19th June, 1964, Edward Kennedy was a passenger in a private plane from Washington to Massachusetts that crashed into an apple orchard in bad weather, in the town of Southampton. The pilot and Edward Moss, one of Kennedy's aides, were killed. Kennedy suffered six spinal fractures and two broken ribs. He spent six months in hospital and suffered chronic back pain from the landing for the rest of his life.

Kennedy returned to the Senate in 1965 and along with Robert Kennedy he joined the campaign for the 1965 Voting Rights Act. He tried to strengthen it with an amendment that would have outlawed poll taxes. He lost by only four votes, and showed for the first time his committment to liberal causes.

Initially, Edward Kennedy gave his support to Lyndon B. Johnson when he expanded the U.S. role in the Vietnam War. However, he grew increasingly concerned about the large number of American deaths and after a trip to the country in January 1968 he argued that the president should tell South Vietnam, "Shape up or we're going to ship out." Later he called the war a “monstrous outrage.”

On 16th March, Robert Kennedy declared his candidacy for the presidency, stating, "I am today announcing my candidacy for the presidency of the United States. I do not run for the Presidency merely to oppose any man, but to propose new policies. I run because I am convinced that this country is on a perilous course and because I have such strong feelings about what must be done, and I feel that I'm obliged to do all I can." Edward Kennedy became his brother's leading campaigner.

Soon afterwards Lyndon B. Johnson withdrew from the contest and Robert Kennedy looked certain to be the party's candidate. He had just won his sixth primary in California when he was assassinated. Frank Mankiewicz said of seeing Edward at the hospital where Robert lay mortally wounded: "I have never, ever, nor do I expect ever, to see a face more in grief."

At his brother's funeral, Edward Kennedy gave a speech that included: "Few are willing to brave the disapproval of their fellows, the censure of their colleagues, the wrath of their society. Moral courage is a rarer commodity than bravery in battle or great intelligence. Yet it is the one essential, vital quality for those who seek to change a world that yields most painfully to change." He then went onto quote his brother: "Some men see things as they are and say why. I dream things that never were and say why not."

Edward Kennedy developed a drink problem after the death of Robert Kennedy. One of his biographers has pointed out: "The strain began to show on Kennedy, notably in his increased consumption of alcohol. It surfaced publicly when he went on a Senate fact-finding trip to Alaska the following spring. His staff and the accompanying journalists noticed him taking constant drags from a hip flask on the flights and then searching out bars at each stop. On the homeward flight he repeatedly teetered down the aisle, spilling his drinks on other passengers. He was also having difficulties with his marriage. Like his father and brother John, he had a voracious sexual appetite."

After Richard Nixon was elected in 1968 Edward Kennedy was widely assumed to be the front-runner for the 1972 Democratic nomination. In January 1969, Kennedy was elected as Senate Majority Whip, the youngest person to attain that position. In this role he made determined efforts to stop Nixon's plans to cut back on welfare and other federal programmes for the poor.

On 17th July, 1969, Mary Jo Kopechne joined several other women who had worked for the Kennedy family at the Edgartown Regatta. She stayed at the Katama Shores Motor Inn on the southern tip of Martha's Vineyard. The following day the women travelled across to Chappaquiddick Island. They were joined by Ted Kennedy and that night they held a party at Lawrence Cottage. At the party was Kennedy, Kopechne, Susan Tannenbaum, Maryellen Lyons, Ann Lyons, Rosemary Keough, Esther Newburgh, Joe Gargan, Paul Markham, Charles Tretter, Raymond La Rosa and John Crimmins.

Mary Jo Kopechne and Kennedy left the party at 11.15pm. Kennedy had offered to take Kopechne back to her hotel. He later explained what happened: "I was unfamiliar with the road and turned onto Dyke Road instead of bearing left on Main Street. After proceeding for approximately a half mile on Dyke Road I descended a hill and came upon a narrow bridge. The car went off the side of the bridge.... The car turned over and sank into the water and landed with the roof resting on the bottom. I attempted to open the door and window of the car but have no recollection of how I got out of the car. I came to the surface and then repeatedly dove down to the car in an attempt to see if the passenger was still in the car. I was unsuccessful in the attempt."

Instead of reporting the accident Edward Kennedy returned to the party. According to a statement issued by Kennedy on 25th July, 1969: "instead of looking directly for a telephone number after lying exhausted in the grass for an undetermined time, walked back to the cottage where the party was being held and requested the help of two friends, my cousin Joseph Gargan and Paul Markham, and directed them to return immediately to the scene with me - this was some time after midnight - in order to undertake a new effort to dive."

When this effort to rescue Mary Jo Kopechne ended in failure, Kennedy decided to return to his hotel. As the ferry had shut down for the night Kennedy, swam back to Edgartown. It was not until the following morning that Kennedy reported the accident to the police. By this time the police had found Mary Jo Kopechne's body in Kennedy's car.

Edward Kennedy was found guilty of leaving the scene of the accident and received a suspended two-month jail term and one-year driving ban. That night he appeared on television to explain what had happened. He explained: "My conduct and conversations during the next several hours to the extent that I can remember them make no sense to me at all. Although my doctors informed me that I suffered a cerebral concussion as well as shock, I do not seek to escape responsibility for my actions by placing the blame either on the physical, emotional trauma brought on by the accident or on anyone else. I regard as indefensible the fact that I did not report the accident to the police immediately."

At the inquest Judge James Boyle raised doubts about Kennedy's testimony. He pointed out that as Kennedy had a good knowledge of Chappaquiddick Island he could not understand how he managed to drive down Dyke Road by mistake. For example, on the day of the accident, Kennedy had twice had driven on Dyke Road to go to the beach for a swim. To get to Dyke Road involved a 90-degree turn off a metalled road onto the rough, bumpy dirt-track.

An investigation at the scene of the accident by Raymond R. McHenry, suggested that Kennedy approached the bridge at an estimated 34 miles (55 kilometres) per hour. At around 5 metres (17 feet) from the bridge, Kennedy braked violently. This locked the front wheels. According to McHenry: "The car skidded 5 metres (17 feet) along the road, 8 metres (25 feet) up the humpback bridge, jumped a 14 centimetre barrier, somersaulted through the air for about 10 metres (35 feet) into the water and landed upside-down."

Investigators found it difficult to understand why he was crossing Dyke Bridge when he said he was attempting to reach Edgartown which was in the opposite direction. They also could not understand why he was driving so fast on this unlit, uneven, road. They also could not work out how Kennedy escaped from the car. When it was recovered from the water all the doors were locked. Three of the windows were either open or smashed in. If Kennedy, a large-framed 6 foot 2 inches tall man could manage to get out of the car, why was it impossible for Kopechne, a slender 5 foot 2 inches tall, not do the same?

Local experts could not understand why Kennedy (and later, Markham and Gargan) could not rescue Kopechne from the car. It also surprised investigators that Kennedy did not seek help from Pierre Malm, who only lived 135 metres from the bridge. At the inquest Kennedy was unable to answer this question.

There were also doubts about the way Mary Jo Kopechne died. Dr. Donald Mills of Edgartown, wrote on the death certificate: "death by drowning". However, Gene Frieh, the undertaker, told reporters that death "was due to suffocation rather than drowning". John Farrar, the diver who removed Kopechne from the car, claimed she was "too buoyant to be full of water". It is assumed that she died from drowning, although her parents filed a petition preventing an autopsy.

Other questions were asked about Kennedy's decision to swim back to Edgartown. The 150 metre channel had strong currents and only the strongest of swimmers would have been able to make the journey safely. Also no one saw Kennedy arrive back at the Shiretown Inn in wet clothes. Ross Richards, who had a conversation with Kennedy the following morning at the hotel described him as casual and at ease.

Kennedy did not inform the police of the accident while he was at the hotel. Instead at 9am he joined Gargan and Markham on the ferry back to Chappaquiddick Island. Steve Ewing, the ferry operator, reported Kennedy in a jovial mood. It was only when Kennedy reached the island that he phoned the authorities about the accident that had taken place the previous night.

Dr. Robert Watt, Kennedy's family doctor, explained his patient's strange behaviour by claiming he was in a state of shock and confusion and "possible concussion."

President Richard Nixon told his White House chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman that this was "the end of Teddy" and that it "will be around his neck forever." Max Lerner wrote in Ted and the Kennedy Legend: A Study in Character and Destiny (1980), this self-inflicted wound, more than any other event, "blocked his path to the White House, called his credibility into question and damaged the Kennedy legend."

The Chappaquiddick incident continued to haunt Kennedy and in January 1971, he lost his position as Senate Majority Whip when he was defeated by Senator Robert Byrd, 31–24. Kennedy now concentrated on wider political issues. This included becoming chair of the Senate subcommittee on health care. Over the next few years Edward Kennedy developed a well-deserved reputation in Capitol Hill as a diligent and effective legislator.

As Evan Thomas pointed out in Newsweek: "Edward Kennedy, perhaps more than any United States senator in the past half century, cared about the poor and dispossessed. Though he was relentlessly mocked by the right as a tax-and-spend liberal, he kept the faith.... He was hardly the first rich person to care. Oblige has gone with noblesse for ages; Franklin Roosevelt, creator of the New Deal, was a rich aristocrat. But there was a seriousness, a doggedness, to Kennedy. He was no dilettante, no limousine liberal. He was a prodigious worker, the strongest force in the government for women's rights and health care, civil rights and immigration, the rights of the disabled and education. He was effective: in the Senate, to get something done, you went to Ted Kennedy."

Kennedy was also an outspoken critic of President Richard Nixon. He made several speeches attacking Nixon's policies in Vietnam. He called it "a policy of violence that means more and more war". Kennedy also strongly criticized the Nixon administration's support for Pakistan and its ignoring of "the brutal and systematic repression of East Bengal by the Pakistani army".

However, because of the death of Mary Jo Kopechne, Kennedy was not in a position to obtain the nomination to take on Nixon in the 1972 presidential election. As one commentator has pointed out: "The judge ruled that Kennedy was probably guilty of criminal conduct but made no move to indict him. This obvious manipulation of the local judiciary by the state's most powerful family was probably more damaging in the long term than the tragedy itself."

Edward Kennedy and Joan Bennett Kennedy had three children: Kara Anne (27th February, 1960), Edward Moore Kennedy, Jr. (26th September, 1961) and Patrick Joseph Kennedy (14th July, 1967). The children encountered several health problems. Patrick suffered from severe asthma attacks and in 1973 Edward was discovered to have bone cancer and had to have his right leg amputated. Joan has also had three miscarriages and this contributed to her developing a serious drink problem. In 1978, the couple separated and shortly afterwards she gave an interview to McCall's Magazine where she admitted to being an alcoholic.

In 1979 Kennedy made another attempt to become the Democratic Party presidential candidate when he took on the sitting president, Jimmy Carter, a member of his own party. Kennedy won 10 presidential primaries but he eventually withdrew from the race when it became clear that the public was still concerned about the events on Chappaquiddick Island. When he withdrew from the campaign he made a speech where he argued: "For me, a few hours ago, this campaign came to an end. For all those whose cares have been our concern, the work goes on, the cause endures, the hope still lives, and the dream shall never die."

Edward Kennedy and Joan Bennett Kennedy divorced in 1982. Kennedy easily defeated Republican businessman Ray Shamie to win re-election in 1982. He was already the ranking member of the Labor and Public Welfare Committee but Senate leaders also granted him a seat on the Armed Services Committee. Kennedy now became an outspoken critic of the foreign policy of President Ronald Reagan. This included intervention in the Salvadoran Civil War and the support for the Contras in Nicaragua.

Kennedy also objected to the support President Reagan gave to apartheid government in South Africa. In January 1985 he visited the country and spent a night in the Soweto home of Bishop Desmond Tutu and also visited Winnie Mandela, wife of imprisoned black leader Nelson Mandela. On his return to the United States he campaigned for economic sanctions against South Africa and was mainly responsible for the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986. President Reagan attempted to veto the legislation but was overridden by the United States Congress (by the Senate 78 to 21, the House by 313 to 83). This was the first time in the 20th century that a president had a foreign policy veto overridden. Later that year he travelled to the Soviet Union where he had talks with Mikhail Gorbachev. This led to the release of several political prisoners, including Anatoly Shcharansky.

In 1991, Kennedy was involved in another scandal when his nephew William Kennedy Smith was accused of sexual offences against Patricia Bowman while at a party at the family's Palm Beach, Florida estate. Smith was eventually acquitted and even though he was not directly implicated in the case he issued a public statement about his life: " "I am painfully aware of the disappointment of friends and many others who rely on me to fight the good fight. I recognise my own shortcomings, the faults in the conduct of my private life."

Ted Kennedy met Victoria Reggie, a Washington lawyer at Keck, Mahin & Cate, on 17th June 1991. They were married on 3rd July, 1992, in a civil ceremony at Kennedy's home in McLean, Virginia.

Kennedy remained on the left of the party and has been identified with various progressive causes. He was achairman of the United States Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions. In 2007 he helped pass the Fair Minimum Wage Act, which incrementally raises the minimum wage by $2.10 to $7.25 over a two year period. The bill also included higher taxes for many $1 million-plus executives. Kennedy was quoted as saying, "Passing this wage hike represents a small, but necessary step to help lift America's working poor out of the ditches of poverty and onto the road toward economic prosperity."

On May 20, 2008, doctors announced that Kennedy has a malignant brain tumor, diagnosed after he experienced a seizure at Hyannisport. The following month Kennedy underwent brain surgery at Duke University Hospital.

During his last months Kennedy, who was chairman of the Senate health committee, used what energy he had left to try and get the proposal by Barack Obama, to extend insurance coverage to 46 million people. Kennedy described health reform as the "cause of my life". As The Washington Post pointed out: "His measures gave access to care for millions and funded treatment around the world. He was a longtime advocate for universal health care and promoted biomedical research, as well as AIDS research and treatment."

Edward Kennedy died on 26th August 2009. Nancy Pelosi, in a statement on Kennedy's death, vowed that a health reform bill would reach the statute book this year. "Ted Kennedy's dream of quality healthcare for all Americans will be made real this year because of his leadership and his inspiration." Marc R. Stanley, chairman of the National Jewish Democratic Council, said: "Kennedy dedicated much of his life to ensuring that affordable healthcare is available for all Americans. The greatest tribute that we can bestow is to thoughtfully, but urgently, enact comprehensive health insurance reform."

Primary Sources

(1) Edward Kennedy, Tribute to Robert Kennedy (8th June 1968)

These men moved the world, and so can we all. Few will have the greatness to bend history itself, but each of us can work to change a small portion of events, and in the total of all those acts will be written the history of this generation. It is from numberless diverse acts of courage and belief that human history is shaped. Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, those ripples build a current that can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.

Few are willing to brave the disapproval of their fellows, the censure of their colleagues, the wrath of their society. Moral courage is a rarer commodity than bravery in battle or great intelligence. Yet it is the one essential, vital quality for those who seek to change a world that yields most painfully to change. And I believe that in this generation those with the courage to enter the moral conflict will find themselves with companions in every corner of the globe.

For the fortunate among us, there is the temptation to follow the easy and familiar paths of personal ambition and financial success so grandly spread before those who enjoy the privilege of education. But that is not the road history has marked out for us. Like it or not, we live in times of danger and uncertainty. But they are also more open to the creative energy of men than any other time in history. All of us will ultimately be judged, and as the years pass we will surely judge ourselves on the effort we have contributed to building a new world society and the extent to which our ideals and goals have shaped that event.

The future does not belong to those who are content with today, apathetic toward common problems and their fellow man alike, timid and fearful in the face of new ideas and bold projects. Rather it will belong to those who can blend vision, reason and courage in a personal commitment to the ideals and great enterprises of American Society. Our future may lie beyond our vision, but it is not completely beyond our control. It is the shaping impulse of America that neither fate nor nature nor the irresistible tides of history, but the work of our own hands, matched to reason and principle, that will determine our destiny. There is pride in that, even arrogance, but there is also experience and truth. In any event, it is the only way we can live."

That is the way he lived. That is what he leaves us.

My brother need not be idealized, or enlarged in death beyond what he was in life; to be remembered simply as a good and decent man, who saw wrong and tried to right it, saw suffering and tried to heal it, saw war and tried to stop it.

Those of us who loved him and who take him to his rest today, pray that what he was to us and what he wished for others will some day come to pass for all the world.

As he said many times, in many parts of this nation, to those he touched and who sought to touch him: "Some men see things as they are and say why. I dream things that never were and say why not."

(2) John Simkin, Chappaquiddick and the Assassination of JFK (29th August, 2009)

Edward Kennedy and Mary Jo Kopechne left the Lawrence Cottage at around 11.15 p.m. on 18th July, 1969. Kennedy claimed that he was giving her a lift back to her hotel. The last ferry was at 12.00. The party only had two cars. The six women at the party had been told that they would be taken back to their hotels via that ferry.

Although he had been on the island many times Kennedy took the wrong turning. Locals claimed this was almost impossible to do. To make this wrong turn at this point the driver had to ignore: (1) A directional arrow of luminized glass pointing to the left; (2) The banking of the pavement to accommodate the sharp curve; (3) The white line down the centre of the road. (4) The fact that he was now driving on an unpaved road.

According to Kennedy he had the accident on Dike Bridge at 11.30. He made several attempts to rescue Mary Jo. Although there were three houses with lights on close to where the accident happened. Kennedy walked back to Lawrence Cottage. This was a 1.2 mile walk that took approximately 23 minutes. The route involved passing the Chappaquiddick Fire Station. The station was unlocked and included an alarm. The Fire Captain (Foster Silva) lived close by and would have been there within 3 minutes. According to Silva once sounded "half the people living on the island would have turned up within 15 minutes".

Kennedy claimed he got back at the cottage at 12.20 a.m. He got the time from the Valiant car while he sat in the back seat discussing the problem with his two friends, Joe Gargan and Paul Markham. This was a lie. It was later discovered that the Valiant car (rented for the weekend) did not have a clock.

According to their testimony Kennedy, Gargan and Markham then went back to the scene of the accident and tried to get Mary Jo out of the car. After 45 minutes they accepted defeat. Kennedy, told the men he was going to report the accident once back in Edgartown. He then swam back as he thought the last ferry had gone. This was a risky thing to do and as Kennedy admitted afterwards, he nearly drowned getting to his hotel.

Gargan and Markham claimed they got back to the cottage at around 2.15 a.m. If so, this leaves an hour accounted for. This point was not explored at the inquest.

Jared Grant operated the Chappaquiddick Ferry. The last ferry usually went at midnight. However, that night his last run was 12.45 a.m. He did not actually close the ferry until 1.20 a.m. He later testified that he saw several boats "running back and forth" between the island and Edgartown. During this period he was never approached by Kennedy, Gargan or Markham.

That night Kennedy spoke to the room clerk at the Shiretown Inn at 2.30 a.m. According to Gargan this was to establish an alibi. At this stage he intended to claim he had not been driving the car.

Records show that Kennedy did not make any phone calls from the hotel. All his close political advisers confirm they did not receive calls from Kennedy that night. If they had, they would have told him to report the accident straight away. Kennedy made his first call (to Helga Wagner) a 8 a.m. the next morning.

Two friends of Kennedy, Ross Richards and Stan Moore, met with him in his hotel just before 8 o'clock. They reported that he appeared to be acting in a relaxed way and did not appear to be under any stress. Soon afterwards, Paul Markham and Joe Gargan arrived at the hotel. According to Richards they were "soaking wet". It was while talking to Markham and Gargan that Kennedy became visibly upset.

Lieutenant George Killen, who interviewed all those people who had contact with Kennedy that morning in the hotel, became convinced that it was at this stage that Kennedy first discovered that Mary Jo Kopechne was dead. Richards also agreed with this analysis.

Kennedy returned to the island on the ferry at 9.50 the following morning. It was only once back on the island that he reported the accident.

John Farrar, a scuba diver, got the Mary Jo's body out of the car. He believed that she found an air-pocket in the car and probably lived for about an hour. This view was supported by the medical examination of the body. The doctor claimed she had died of suffocation rather than from drowning.

Farrar found it difficult to believe that Kennedy would have been able to get out of the car once it went into the water. Others at the crime scene took a similar view. Lieutenant Bernie Flynn said: "Ted Kennedy wasn't in the car when it went off the bridge. He would never have gotten out alive."

There is one major problem with these timings. At about 12.45 Kennedy's stationary car was seen at the intersection on Dike Road near the bridge by Christopher ‘Huck' Look, deputy sheriff and part-time police officer. Look claims that a man was driving and that two other people were in the car. Look approached the car on foot but when the driver saw his police uniform the car then sped off down Dike Road . The car had a Massachusetts registration letter L. It also had a 7 at the beginning and at the end. Only eight other cars of this type had this number plate. They were all later checked out. Kennedy's car was the only one with that number plate that was on the island that night.

Christopher ‘Huck' Look appears to be a convincing witness. There seems to be no reason why he should lie about what he saw on the morning of the 19th July, 1969.

Therefore we have the situation where Edward Kennedy and Mary Jo Kopechne left the Lawrence Cottage at around 11.15 p.m. For some reason Kennedy returns to the cottage at 12.20 a.m. However, it is not to report the accident as at this stage the car has not yet had the accident on Dike Bridge .

Lieutenant George Killen, who investigated the case, was convinced that Kennedy had intended to have sex with Mary Jo in the car. He was drunk (evidence suppressed in court showed that Kennedy had consumed a great deal of alcohol that day). When Look approached Kennedy's car, he feared he would be arrested. Therefore he sped off into the darkness. Afraid that Look would catch him up he gets out of the car and persuades Mary Jo to drive off (she herself has consumed a fair amount of alcohol. Kennedy then walks back to the cottage. When Mary Jo does not return Kennedy becomes convinced she has had an accident. Kennedy then goes back to his hotel leaving Markham and Gargan to search for Mary Jo. It is not until the next morning they discover what has happened. They then go to Kennedy's hotel to tell him the news. This fits Killen idea that Kennedy did not know about the accident until the morning meeting with Markham and Gargan.

Killen's theory fits all the established facts in the case. However, it does not explain Kennedy's behaviour. Once he discovered that Mary Jo was dead, it would make far more sense to tell the truth. This story was more politically acceptable than the "leaving the scene of the accident" story. I therefore reject Killen's theory.

(3) Report by Detective Bernie Flynn (18th July, 1969)

I figure, we've got a drunk driver, Ted Kennedy. He's with this girl, and he has it in his mind to go down to the beach and make love to her. He's probably driving too fast and he misses the curve and goes into Cemetery Road. He's backing up when he sees this guy in uniform coming toward him. That's panic for the average driver who's been drinking; but here's a United States Senator about to get tagged for driving under. He doesn't want to get caught with a girl in his car, on a deserted road late at night, with no license and driving drunk on top of it. In his mind, the most important thing is to get away from the situation.

He doesn't wait around. He takes off down the road. He's probably looking in the rear-view mirror to see if the cop is following him. He doesn't even see the bridge and bingo! He goes off. He gets out of the car; she doesn't. The poor son of a bitch doesn't know what to do. He's thinking: "I want to get back to my house, to my friends" - which is a common reaction.

There are houses on Dike Road he could have gone to report the accident, but he doesn't want to. Because it's the same situation he was trying to get away from at the corner - which turned out to be minor compared to what happened later. Now there's been an accident; and the girl's probably dead. All the more reason not to go banging on somebody's door in the middle of the night and admit what he was doing. He doesn't want to reveal himself.

And the funny part about it was, 'Huck' was only trying to give his directions.

(4) Edward Kennedy, speech on television (25th July, 1969)

My fellow citizens, I have requested this opportunity to talk to the people of Massachusetts about the tragedy which happened last Friday evening. This morning I entered a plea of guilty to the charge of leaving the scene of the accident. Prior to my appearance in court it would have been improper for me to comment on these matters. But tonight I am free to tell you what happened and to say what it means to me.

On Chappaquiddick Island, off Martha's Vineyard, I attended on Friday evening, July 18, a cookout I had encouraged and helped sponsor for the devoted group of Kennedy campaign secretaries. When I left the party, around 11.15pm, I was accompanied by one of those girls, Miss Mary JO Kopechne. Mary JO was one of the most devoted members of the staff of Senator Robert Kennedy. For this reason, and because she was such a gentle, kind and idealistic person, all of us tried to help her feel that she had a home with the Kennedy family.

There is no truth, no truth whatsoever, to the widely-circulated suspicions of immoral conduct that have been levelled at my behaviour and hers regarding that evening. There has never been a private relationship between us of any kind. I know of nothing in Mary Jo's conduct on that or any other occasion - the same is true of the other girls at that party - that would lend any substance to such ugly speculation about their character. Nor was I driving under the influence of liquor.

Little over one mile away, the car I was driving on an unlit road went off a narrow bridge which had no guard-rails and was built on a left angle to the road. The car overturned in a deep pond and immediately filled with water. I remember thinking as the cold water rushed in around my head that I was for certain drowning. Then water entered my lungs and I actually felt the sensation of drowning. But somehow I struggled to the surface alive. I made immediate and repeated efforts to save Mary JO by diving into the strong and murky current but succeeded only in increasing my state of utter exhaustion and alarm.

My conduct and conversations during the next several hours to the extent that I can remember them make no sense to me at all. Although my doctors informed me that I suffered a cerebral concussion as well as shock, I do not seek to escape responsibility for my actions by placing the blame either on the physical, emotional trauma brought on by the accident or on anyone else. I regard as indefensible the fact that I did not report the accident to the police immediately.

Instead of looking directly for a telephone number affair lying exhausted in the grass for an undetermined time, walked back to the cottage where the party was being held and requested the help of two friends, my cousin Joseph Gargan and Paul Markham, and directed them to return immediately to the scene with me - this was some time after midnight - in order to undertake a new effort to dive.

(5) Leo Damore, Senatorial Privilege: The Chappaquidick Cover-up (1988)

One of the most disputed questions raised by the accident was what time Senator Kennedy left the party with Mary Jo Kopechne.

In his first statement to police, the Senator claimed that he was taking Miss Kopechne to the ferry when the accident occurred. Since ferry service to Edgartown stopped at midnight, his version of events required that he would have had to leave in time to catch the last ferry.

Gargan, who was cleaning up after cooking the meal, thought it could have been as late as 11:50 pm when the Senator left the party. Although he wasn't wearing a watch, he said "I made a mental note - no particular reason - that he was going to make the ferry. When he left, the assumption was that he was going to the landing, but I don't know where he went."

Gargan said "It was very hot, and some people were going for walks. It's possible the Senator went for a walk before getting into the car, or did all kinds of things. I know he still had time to get to the ferry - if he was going to the ferry."

Kennedy didn't announce he was leaving or say good night to anyone. Neither did Mary Jo. Miss Kopeckne left her pocket book behind, and it was found at the cottage the next morning.

Those close to Ted Kennedy claimed that his chauffeur ( Jack Crimmins ) "drove the Senator everywhere." Since Crimmins was present at the party, some thought it was peculiar that he hadn't driven Kennedy and Miss Kopechne to the ferry.

Crimmins testified that the Senator had called him out of the cottage to the front yard and asked for the keys to the car. "He told me that he was tired, and that he was going to take Miss Kopechne back." Crimmins claimed that he didn't want to give Kennedy the keys, and that he had offered to drive him to the ferry landing. Kennedy wanted to drive, however, and because "It was his automobile," Crimmins said, "I gave the keys to him. I didn't question him." Crimmins was certain that Kennedy left at 11:15 pm, "Because I looked at my watch."

(6) Joe Gargan was interviewed by Leo Damore in 1988.

Kennedy told Gargan and Markham that after he had swum the channel, he had slipped into the Shiretown Inn unseen, changed clothes and established his presence by asking an employee patrolling the premises the time. He had gone to bed and awakened around 7 o'clock. He had betrayed no sign of having been involved in an automobile accident to a number of witnesses. It wasn't too late for the scenario he had proposed to be put into effect. It wouldn't be difficult to convince people he hadn't known about the accident until the next morning.

The Senator expected the incident to have been "taken care of " when Gargan and Markham showed up the next morning, that Gargan would have reported the accident and told the police that Mary Jo Kopechne had been driving the accident car. The Senator had counted on Gargan to realize, after an hour or so had passed and nobody showed up at the cottage, that he had no choice but to report the accident. It was, after all, the kind of clean-up detail Gargan customarily performed as advance man, a dependency that went back to the "Joey'll fix it" days of their boyhood. So long as there was a chance Gargan would reconsider his objections to the plan, the Senator had not reported the accident himself.

Gargan was mortified by the Senator's motive for swimming the channel: to force him to follow a course he had made clear he wanted followed, irrespective of Gargan's objections. That the accident had not been reported was bad enough. For the Senator to have misrepresented his intentions by subterfuge, saying he was going to report the accident and then not doing so, and start putting an alibi into play only compounded the tragedy.

Gargan said "This thing is worse now than it was before. We've got to do something. We're reporting the accident right now!"

Kennedy said "I'm going to say that Mary Jo was driving."

"There's no way you can say that!" Gargan said. "You can be placed at the scene. Jesus! We've got to report this thing. Let's go."

Kennedy was reluctant to do so, Markham observed. "He was still stuck on the idea of having Mary Jo driving the car."

(7) W. Penn Jones Jr, Texas Midlothian Mirror (31st July, 1969)

Bobby Baker was about the first person in Washington to know that Lyndon Johnson was to be dumped as the Vice-Presidential candidate in 1964. Baker knew that President Kennedy had offered the spot on the ticket to Senator George Smathers of Florida... Baker knew because his secretary. Miss Nancy Carole Tyler, roomed with one of George Smathers' secretaries. Miss Mary Jo Kopechne had been another of Smathers' secretaries. Now both Miss Tyler and Miss Kopechne have died strangely.

(8) Richard E. Sprague, The Taking of America (1976)

The Power Control Group faced up to the Ted Kennedy and Kennedy family problem very early. They used the threat against the Kennedy children's lives very effectively between 1963 and 1968 to silence Bobby and the rest of the family and friends who knew the truth. It was necessary to assassinate Bobby in 1968 because with the power of the presidency he could have prevented the Group from harming the children. When Teddy began making moves to run for president in 1969 for the 1972 election, the Group decided to put some real action behind their threats. Killing Teddy in 1969 would have been too much. They selected a new way of eliminating him as a candidate. They framed him with the death of a young girl, and threw sexual overtones in for good measure.

Here is what happened according to Robert Cutler's (You the Jury - 1974) analysis of the evidence. The Group hired several men and at least one woman to be at Chappaquiddick during the weekend of the yacht race and the planned party on the island. They ambushed Ted and Mary Jo after they left the cottage and knocked Ted out with blows to his head and body. They took the unconscious or semi-conscious Kennedy to Martha's Vineyard and deposited him in his hotel room. Another group took Mary Jo to the bridge in Ted's car, force fed her with a knock out potion of alcoholic beverage, placed her in the back seat, and caused the car to accelerate off the side of the bridge into the water. They broke the windows on one side of the car to insure the entry of water; then they watched the car until they were sure Mary Jo would not escape.

Mary Jo actually regained consciousness and pushed her way to the top of the car (which was actually the bottom of the car - it had landed on its roof) and died from asphyxiation. The group with Teddy revived him early in the morning and let him know he had a problem. Possibly they told him that Mary Jo had been kidnapped. They told him his children would be killed if he told anyone what had happened and that he would hear from them. On Chappaquiddick, the other group made contact with Markham and Gargan, Ted's cousin and lawyer. They told both men that Mary Jo was at the bottom of the river and that Ted would have to make up a story about it, not revealing the existence of the group. One of the men resembled Ted and his voice sounded something like Ted's. Markham and Gargan were instructed to go the the Vineyard on the morning ferry, tell Ted where Mary Jo was, and come back to the island to wait for a phone call at a pay station near the ferry on the Chappaquiddick side.

The two men did as they were told and Ted found out what had happened to Mary Jo that morning. The three men returned to the pay phone and received their instructions to concoct a story about the "accident" and to report it to the police. The threat against Ted's children was repeated at that time.

Ted, Markham and Gargan went right away to police chief Arena's office on the Vineyard where Ted reported the so-called "accident." Almost at the same time scuba diver John Farror was pulling Mary Jo out of the water, since two boys who had gone fishing earlier that morning had spotted the car and reported it.

Ted called together a small coterie of friends and advisors including family lawyer Burke Marshall, Robert MacNamara, Ted Sorenson, and others. They met on Squaw Island near the Kennedy compound at Hyannisport for three days. At the end of that time they had manufactured the story which Ted told on TV, and later at the inquest. Bob Cutler calls the story, "the shroud." Even the most cursory examination of the story shows it was full of holes and an impossible explanation of what happened. Ted's claim that he made the wrong turn down the dirt road toward the bridge by mistake is an obvious lie. His claim that he swam the channel back to Martha's Vineyard is not believable. His description of how he got out of the car under water and then dove down to try to rescue Mary Jo is impossible. Markham and Gargan's claims that they kept diving after Mary Jo are also unbelievable.

The evidence for the Cutler scenario is substantial. It begins with the marks on the bridge and the position of the car in the water. The marks show that the car was standing still on the bridge and then accelerated off the edge, moving at a much higher speed than Kennedy claimed. The distance the car travelled in the air also confirms this. The damage to the car on two sides and on top plus the damage to the windshield and the rear view mirror stanchion prove that some of the damage had to have been inflicted before the car left the bridge.

The blood on the back and on the sleeves of Mary Jo's blouse proves that a wound was inflicted before she left the bridge. The alcohol in her bloodstream proves she was drugged, since all witnesses testified she never drank and did not drink that night. The fact that she was in the back seat when her body was recovered indicates that is where she was when the car hit the water. There was no way she could have dived downward against the inrushing water and moved from the front to the back seat underneath the upside-down seat back.

The wounds on the back of Ted Kennedy's skull, those just above his ear and the large bump on the top indicate he was knocked out. His actions at the hotel the next morning show he was not aware of Mary Jo's death until Markham and Gargan arrived. The trip to the pay phone on Chappaquiddick can only be explained by his receiving a call there, not making one. There were plenty of pay phones in or near Ted's hotel if he needed to make a private call. The tides in the channel and the direction in which Ted claimed he swam do not match. In addition it would have been a superhuman feat to have made it across the channel (as proven by several professionals who subsequently tried it).

Deputy Sheriff Christopher Look's testimony, coupled with the testimony of Ray LaRosa and two Lyons girls, proves that there were two people in Ted's car with Mary Jo at 12:45 pm. The three party members walking along the road south toward the cottage confirmed the time that Mr. Look drove by. He stopped to ask if they needed a ride. Look says that just prior to that he encountered Ted's car parked facing north at the juncture of the main road and the dirt road. It was on a short extension of the north-south section of the road junction to the north of the "T". He says he saw a man driving, a woman in the seat beside him, and what he thought was another woman lying on the back seat. He remembered a portion of the license plate which matched Ted's car, as did the description of the car. Markham, Gargan and Ted's driver's testimony show that someone they talked to in the pitch black night sounded like Ted and was about his height and build.

None of the above evidence was ever explained by Ted or by anyone else at the inquest or at the hearing on the case demanded by district attorney Edward Dinis. No autopsy was ever allowed on Mary Jo's body (her family objected), and Ted made it possible to fly her body home for burial rather quickly. Kennedy haters have seized upon Chappaquiddick to enlarge the sexual image now being promoted of both Ted and Jack Kennedy. Books like "Teddy Bare" take full advantage of the situation.

Just which operatives in the Power Control Group at the high levels or the lower levels were on Chappaquiddick Island? No definite evidence has surfaced as yet, except for an indication that there was at least one woman and at least three men, one of whom resembled Ted Kennedy and who sounded like him in the darkness. However, two pieces of testimony in the Watergate hearings provide significant clues as to which of the known JFK case conspirators may have been there.

E. Howard Hunt told of a strange trip to Hyannisport to see a local citizen there about the Chappaquiddick incident. Hunt's cover story on this trip was that he was digging up dirt on Ted Kennedy for use in the 1972 campaign. The story does not make much sense if one questions why Hunt would have to wear a disguise, including his famous red wig, and to use a voice-alteration device to make himself sound like someone else. If, on the other hand, Hunt's purpose was to return to the scene of his crime just to make sure that no one who might have seen his group at the bridge or elsewhere would talk, then the disguise and the voice box make sense.

The other important testimony came from Tony Ulasewicz who said he was ordered by the Plumbers to fly immediately to Chappaquiddick and dig up dirt on Ted. The only problem Tony has is that, according to his testimony, he arrived early on the morning of the "accident", before the whole incident had been made public. Ulasewicz is the right height and weight to resemble Kennedy and with a CIA voice-alteration device he presumably could be made to sound like him. There is a distinct possibility that Hunt and Tony were there when it happened.

The threats by the Power Control Group, the frame-up at Chappaquiddick, and the murders of Jack and Bobby Kennedy cannot have failed to take their toll on all of the Kennedys. Rose, Ted, Jackie, Ethel and the other close family members must be very tired of it all by now. They can certainly not be blamed for hoping it will all go away. Investigations like those proposed by Henry Gonzalez and Thomas Downing only raised the spectre of the powerful Control Group taking revenge by kidnapping some of the seventeen children.

It was no wonder that a close Kennedy friend and ally in California, Representative Burton, said that he would oppose the Downing and Gonzalez resolutions unless Ted Kennedy put his stamp of approval on them. While the sympathies of every decent American go out to them, the future of our country and the freedom of the people to control their own destiny through the election process mean more than the lives of all the Kennedys put together. If John Kennedy were alive today he would probably make the same statement.

(9) Ewen MacAskill, The Guardian (27th August 2009)

Senior Democrats in Congress today signalled their intention to exploit sympathy over Ted Kennedy's death to try to tilt the balance in favour of President Barack Obama's struggling healthcare reform proposals.

Momentum for health legislation that would stand as a tribute to Kennedy started to build today.

Kennedy's death robs the Democrats of their crucial 60-seat majority in the Senate and means they no longer automatically have the numbers to override Republican delaying tactics. But the Democratic leadership is hoping that loss of its arithmetical advantage will be outweighed by the fact that sympathy for Kennedy may help reunite Democratic senators divided over health.

Kennedy, who was chairman of the Senate health committee, described health reform as the "cause of my life".

House speaker Nancy Pelosi, in a statement on Kennedy's death, vowed that a health reform bill would reach the statute book this year. "Ted Kennedy's dream of quality healthcare for all Americans will be made real this year because of his leadership and his inspiration," she said.

Harry Reid, the Democratic leader in the Senate, in his statement, said: "As we mourn his loss, we rededicate ourselves to the causes for which he so dutifully dedicated his life."

Obama set a deadline of October for passage of a reform bill that would extend insurance coverage to 46 million people but Republicans have mounted a successful campaign against it, highlighted by angry town hall meetings across the country.

Senators, including Kennedy's friend, Republican John McCain, expressed the view that his absence from the health debate over the last few months may partly explain why the proposals have ended up in trouble.

Kennedy, whose role on the health committee was taken by the less effective Chris Dodd, has not attended the Senate since April and calls from his sickbed to fellow senators were few.

The key Senate vote on health has been pencilled in for next month. At present, such a bill is in the balance, in danger of either being voted down or passed in a much watered-down form. But the emotions surrounding Kennedy might tip some senators behind it, particularly if it is portrayed as the Kennedy health reform bill.

Kennedy's former press secretary and Democratic strategist Bob Schrum, told ABC today: "It was the cause of his life and he fought it all the way to the end of his life. Maybe his absence now will cast a long shadow and actually make it happen."

Marc Stanley, chairman of the National Jewish Democratic Council, said: "Kennedy dedicated much of his life to ensuring that affordable healthcare is available for all Americans. The greatest tribute that we can bestow is to thoughtfully, but urgently, enact comprehensive health insurance reform."

Obama, in a televised statement, was careful to concentrate only on Kennedy's life and avoided tying his death to the political debate. But the White House adviser, David Axelrod, in a television interview, said Kennedy had remained involved in the heath debate: "He was to the end very much interested and very much committed to seeing this become a reality."

The emotion over Kennedy, while unlikely to move many, or any, Republicans, could influence some of the fiscally conservative Democrats known as the Blue Dogs, who pose the biggest threat to Obama's health plans.

(10) John M. Broder, New York Times (26th August, 2009)

As he underwent cancer treatment, Mr. Kennedy was little seen in Washington, appearing most recently at the White House in April as Mr. Obama signed a national service bill that bears the Kennedy name. In a letter last week, Mr. Kennedy urged Massachusetts lawmakers to change state law and let Gov. Deval Patrick appoint a temporary successor upon his death, to assure that the state’s representation in Congress would not be interrupted.

While Mr. Kennedy was physically absent from the capital in recent months, his presence was deeply felt as Congress weighed the most sweeping revisions to America’s health care system in decades, an effort Mr. Kennedy called “the cause of my life.”

On July 15, the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, which Mr. Kennedy headed, passed health care legislation, and the battle over the proposed overhaul is now consuming Capitol Hill.

Mr. Kennedy was the last surviving brother of a generation of Kennedys that dominated American politics in the 1960s and that came to embody glamour, political idealism and untimely death. The Kennedy mystique — some call it the Kennedy myth — has held the imagination of the world for decades, and it came to rest on the sometimes too-narrow shoulders of the brother known as Teddy.

Born to one of the wealthiest American families, Mr. Kennedy spoke for the downtrodden in his public life while living the heedless private life of a playboy and a rake for many of his years. Dismissed early in his career as a lightweight and an unworthy successor to his revered brothers, he grew in stature over time by sheer longevity and by hewing to liberal principles while often crossing the partisan aisle to enact legislation. A man of unbridled appetites at times, he nevertheless brought a discipline to his public work that resulted in an impressive catalog of legislative achievement across a broad landscape of social policy.

Mr. Kennedy left his mark on legislation concerning civil rights, health care, education, voting rights and labor. He was chairman of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions at his death. But he was more than a legislator. He was a living legend whose presence ensured a crowd and whose hovering figure haunted many a president.

Although he was a leading spokesman for liberal issues and a favorite target of conservative fund-raising appeals, the hallmark of his legislative success was his ability to find Republican allies to get bills passed. Perhaps the last notable example was his work with President George W. Bush to pass No Child Left Behind, the education law pushed by Mr. Bush in 2001. He also co-sponsored immigration legislation with Senator John McCain, the 2008 Republican presidential nominee. One of his greatest friends and collaborators in the Senate was Orrin G. Hatch, the Utah Republican.

Mr. Kennedy had less impact on foreign policy than on domestic concerns, but when he spoke, his voice was influential. He led the Congressional effort to impose sanctions on South Africa over apartheid, pushed for peace in Northern Ireland, won a ban on arms sales to the dictatorship in Chile and denounced the Vietnam War. In 2002, he voted against authorizing the Iraq war; later, he called that opposition “the best vote I’ve made in my 44 years in the United States Senate.”

(11) BBC report (26th August 2009)

On July 18 1969, he was at a party on the small Massachusetts island of Chappaquiddick with a group, including six women known as the boiler room girls, who had worked in his brother Robert's presidential campaign.

Kennedy left the party, supposedly to drive his brother's former secretary, Mary Jo Kopechne, to catch the last ferry back to the mainland but, instead, the car turned onto a side road and crashed off a bridge into a tidal creek.

Kennedy pulled himself from the upturned car and, after swimming across a narrow creek, returned to his hotel without reporting the accident.

It was the following morning before local fishermen found the sunken car and discovered the body of Mary Jo Kopechne still inside.

Evidence given at the subsequent inquest suggested that she had probably remained alive in an air pocket for several hours and might well have been saved had the alarm been raised at the time.

Kennedy pleaded guilty to leaving the scene of an accident, claiming that he had been in shock, and was given a two-month suspended jail sentence.

An inquest, held in secret at the request of Kennedy family lawyers, cast serious doubts on Kennedy's story, but no further action was taken.

This led to suspicions of a cover-up and the incident effectively ended any hopes Kennedy had of attaining the White House.

(12) The Daily Telegraph (26th August 2009)

All Teddy Kennedy’s ambitions, however, foundered on the events of the night of July 18 1969, when he left a party with Mary Jo Kopechne (who had worked on Bobby Kennedy’s presidential campaign the year before), and drove a big, black Oldsmobile off a rickety wooden bridge at Chappaquiddick, Massachusetts, into an 8ft-deep tidal pool. He managed to escape — he could not remember how — but Mary Jo Kopechne was trapped in the car.

Kennedy, on his own account, “repeatedly dove down and tried to see if the passenger was still in the car”, but was unsuccessful. Rather than raise the alarm, however, he returned to the cottage where the party had been, slumped into a parked car, summoned two friends (both of them lawyers), and went back with them to the bridge, where they tried in vain to rescue Mary Jo Kopechne.

Although there was a pay-phone near the bridge, no one contacted the police. Instead, Kennedy swam back to the inn where he was lodged. At 2.25, some three hours after the accident, he emerged, dry and neatly dressed from his room, and asked the proprietor what time it was. Next morning, before breakfast at 8am, he was seen calmly reading a newspaper in the lobby of the inn.

He then returned to his room where he again met the two lawyers, and made several telephone calls. By the time he went to the police the car had already been found, with Mary Jo Kopechne dead inside it.

Kennedy himself later admitted that his behaviour was “inexplicable”, even while attempting to account for it by saying that he must have been in a state of shock, and a neuro-surgeon did indeed diagnose “concussion”. It could not but seem, however, that he had tried to save his own reputation before exhausting all means of saving Mary Jo Kopechne’s life.

Kennedy pleaded guilty to leaving the scene of an accident, and was given a two months’ suspended sentence. In a televised address to the people of Massachusetts that night, he admitted that his conduct had been “indefensible”. At the same time he denied rumours of being drunk or having “a private relationship” with Miss Kopechne. In a well-calculated display of repentance, he then asked voters to tell him if his behaviour had impaired his standing to such an extent that he should resign as senator.

The response was satisfactory enough to allow him to announce on July 30 that he would remain in office. In 1970 he was re-elected to the Senate. But he was never able completely to lay the ghost of Chappaquiddick.

(13) Joe Holley, Washington Post (27th August, 2009)

Instead of president, Edward Kennedy became a major presence in the Senate, to which he was elected largely on the basis of his name in 1962 and where he wore proudly the label of liberal. For decades, Sen. Kennedy helped to shape the national debate. Defending the poor and politically disadvantaged, he staked out his party's positions on health care, education, civil rights, campaign finance reform and labor law.

He also came to oppose the war in Vietnam, and, from the beginning, was an outspoken opponent of the war in Iraq...

Leaders on nearly every continent noted Sen. Kennedy's impact on resolving political conflicts over race, religion and sect, whether in Northern Ireland or in South Africa under apartheid. He pushed for economic sanctions against South Africa's all-white regime and joined protests outside the prison that held Nelson Mandela. He "made his voice heard in the struggle against apartheid at a time when the freedom struggle was not widely supported in the West," the Nelson Mandela Foundation said in a statement yesterday.

Congressional scholar Thomas E. Mann, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, described Edward Kennedy's mark on the Senate as "an amazing and endurable presence. You want to go back to the 19th century to find parallels, but you won't find parallels. It was the completeness of his involvement in the work of the Senate that explains his career."

Opponents caricatured him as a symbol of liberal excess. Yet he was perhaps the most popular of senators, with many friends across the aisle. Through compromise, he could attract their votes....

Sen. Kennedy called health care "the cause of my life." His measures gave access to care for millions and funded treatment around the world. He was a longtime advocate for universal health care and promoted biomedical research, as well as AIDS research and treatment. He championed the Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990 and the 1996 Kennedy-Kassebaum bill - with Sen. Nancy Kassebaum (R-Kan.) -- which allowed employees to keep health insurance after leaving their job.

"Do we really care about our fellow citizens?" he asked countless times, in one form or another, during his long Senate career. He faced opposition from most Republicans - and more than a few Democrats - who said his proposals for universal health care amounted to socialized medicine that would lead to bureaucratic sclerosis and budget-breaking costs and inefficiencies.

(14) Evan Thomas, Newsweek (26th August 2009)

The "careless rich." at times in his life, Edward M. Kennedy seemed to embody the type. Like many scions of wealth, he did not carry money - other people had to pick up the bill. If he drove too fast, there was someone to pay, or fix, the ticket. He was, after all, a Kennedy - "the most exclusive club in the world," the proud patriarch, Joseph Kennedy, liked to proclaim. Kennedys, including Teddy Kennedy, could come off as entitled to the point of irresponsibility, certainly in their messy personal lives.

And yet, Edward Kennedy, perhaps more than any United States senator in the past half century, cared about the poor and dispossessed. Though he was relentlessly mocked by the right as a tax-and-spend liberal, he kept the faith. "For all those whose cares have been our concern, the work goes on, the cause endures, the hope still lives, and the dream shall never die," he said in his most famous speech, at the Democratic National Convention in 1980, and he stayed true to his words.

He was hardly the first rich person to care. Oblige has gone with noblesse for ages; Franklin Roosevelt, creator of the New Deal, was a rich aristocrat. But there was a seriousness, a doggedness, to Kennedy. He was no dilettante, no limousine liberal. He was a prodigious worker, the strongest force in the government for women's rights and health care, civil rights and immigration, the rights of the disabled and education. He was effective: in the Senate, to get something done, you went to Ted Kennedy....

Kennedy upstaged Carter at the Democratic National Convention with his evocative speech promising that "the dream shall never die." And then, knowing that he could never be president, he was finally liberated to do what he was really good at—getting Congress to pass laws to help the downtrodden. During the Reagan years, he defended liberalism like a lion. But he worked behind the scenes to forge alliances across the aisle that kept alive liberal legislation.

Still, the ghosts remained. Or maybe he really was careless. Kennedy watchers, even friends, still refer to his "bad-boy period," which seemed to go on for more than a decade. Joan Kennedy, then an alcoholic and unable to keep up with the athletic, prolific Ethel Kennedy on the tennis court or in the nursery, was, by the late 1960s, married to Teddy in name only. The last straw, she believed, was being required to attend Mary Jo Kopechne's funeral while she was pregnant, at a time when she should have been on bed rest. She miscarried - her third in a row. The two would later divorce. Kennedy became known on Capitol Hill for his antics. In a WashingtonMonthly essay titled "Kennedy's Woman Problem, Women's Kennedy Problem," author Suzannah Lessard accused Kennedy of "a severe case of arrested development, a kind of narcissistic intemperance, a huge babyish ego that must be constantly fed." More like it, a huge sadness that needed to be blotted out by sex and alcohol.

Kennedy was a reliable and diligent senator. Every night he took home what his staffers called "the Bag," stuffed with briefing papers and documents that Kennedy studied and marked up. He was, after the death of his brothers, the paterfamilias of the extended Kennedy family—loving, warm, and involved, but not exactly a role model. The Kennedy cousins were known as hard partyers, and their shenanigans were bound to end badly.

(15) Martin F. Nolan, The Boston Globe (27th August 2009)

On July 18, 1969, Mansfield predicted that his colleague would not run for president in 1972, saying “He’s in no hurry. He’s young. He likes the Senate.’’

On that same day, Senator Kennedy arrived on an island that his actions would make notorious. On Chappaquiddick, across a narrow inlet from Edgartown on Martha’s Vineyard, six young women who had worked on Robert Kennedy’s campaign gathered for a reunion at a rented cottage. Senator Kennedy’s marriage was already troubled, and he had been seen in the company of other glamorous women. But the women at Chappaquiddick were all serious, professional political operatives.

Mary Jo Kopechne, 28, had worked for RFK’s Senate office. A passenger in a car driven by Ted Kennedy, she drowned after the car skidded off a bridge. Senator Kennedy failed to report the accident for 10 hours. The crash gave him a minor concussion and a major personal and political crisis.

As American astronauts walked on the moon, fulfilling a JFK pledge, Chappaquiddick was front-page news across the globe. The senator was unable to explain the accident for days. After consulting in Hyannis Port with his brothers’ advisers and speechwriters, he gave a televised speech a week later. He praised Kopechne and attacked “ugly speculation about her character,’’ wondered aloud “whether some awful curse did actually hang over the Kennedys,’’ then asked Massachusetts voters whether he should resign. They replied overwhelmingly: No.

His critics snarled that Senator Kennedy “got away with it’’ at Chappaquiddick, but the price he paid in personal grief was as high as the cost in presidential politics. During the Cold War, voters expected quick and cool judgment from presidents. Senator Kennedy, in effect, disqualified himself when he confessed on television that he should have alerted police immediately: “I was overcome, I’m frank to say, by a jumble of emotions: grief, fear, doubt, exhaustion, panic, confusion, and shock.’’

(16) Joyce Carol Oates, The Guardian (27th August 2009)

"There are no second acts in American lives" - this dour pronouncement of F Scott Fitzgerald has been many times refuted, and at no time more appropriately than in reference to the late Senator Ted Kennedy, whose death was announced yesterday. Indeed, it might be argued that Senator Kennedy's career as one of the most influential of 20th-century Democratic politicians, an iconic figure as powerful, and as morally enigmatic, as President Bill Clinton, whom in many ways Kennedy resembled, was a consequence of his notorious behaviour at Chappaquiddick bridge in July 1969.

Yet, ironically, following this nadir in his life/ career, Ted Kennedy seemed to have genuinely refashioned himself as a serious, idealistic, tirelessly energetic liberal Democrat in the mold of 1960s/1970s American liberalism, arguably the greatest Democratic senator of the 20th century. His tireless advocacy of civil rights, rights for disabled Americans, health care, voting reform, his courageous vote against the Iraq war (when numerous Democrats including Hillary Clinton voted for it) suggest that there are not only "second acts" in American lives, but that the Renaissance concept of the "fortunate fall" may be relevant here: one "falls" as Adam and Eve "fell"; one sins and repents and is forgiven, provided that one remakes one's life.

Kennedy was 36, a senator from Massachusetts whose political career had been managed by his father Joseph Kennedy and facilitated by family wealth, as his expulsion from Harvard as an undergraduate for cheating on a final examination was rectified by family pressure. Like George Bush, another spoiled younger brother of a well-to-do and influential family whose subsequent success in politics had little to do with his own evident talent, intelligence, or ambition, Ted Kennedy was groomed for public office despite dubious qualifications.

At Chappaquiddick, having been drinking and partying with young women aides of his brother Robert Kennedy, Senator Kennedy, at this time a married man and a father, slipped away with 28-year-old Mary Jo Kopechne, who was trapped in his car after he took a wrong turn off the Chappaquiddick bridge, lost control of his car which was submerged in just eight feet of water.

Kennedy chose to flee the scene , leaving the young woman to die an agonising death not of drowning but of suffocation over a period of hours. Incredibly, it was 10 hours before Kennedy reported the accident, by which time he'd consulted a family lawyer. The senator's explanation for this unconscionable, despicable, unmanly and inexplicable behaviour was never convincing: he claimed that he'd struck his head and was "confused" and "exhausted" from diving and trying to rescue the young woman and had gone home to bed.

There followed a media circus, as all of the world rushed to Chappaquiddick to expose Kennedy's behaviour and to speculate on his future. Yet, appealing to his lawyer and not rather seeking emergency help for the trapped Mary Jo Kopechne would seem, in retrospect, to have been a felicitous move.

If Kennedy had summoned aid, he would very likely have given police officers self-incriminating evidence, which might have involved charges of vehicular manslaughter or homicide. The local prosecutor was not nearly so outraged by Kennedy's behaviour as other prosecutors might have been: the charges were "failing to report an accident" and "leaving the scene of an accident." The punishment: two months' probation.

That the Kennedys had always been a family operating outside the perimeters of the sort of legal restrictions that bind other citizens to "moral" behaviour publicly, is well known; no occasion so exemplifies this than Chappaquiddick and the subsequent cooperative silence of the Kopechne family who agreed never to speak of the tragedy.

One is led to think of Tom and Daisy Buchanan of Fitzgerald's the Great Gatsby, rich individuals accustomed to behaving carelessly and allowing others to clean up after them. It is often in instances of the "fortunate fall", think of Joseph Conrad's anti-hero/hero Lord Jim as a classic literary analogy, that innocent individuals figure almost as ritual sacrifices is another aspect of the phenomenon.

Yet if one weighs the life of a single young woman against the accomplishments of the man President Obama has called the greatest Democratic senator in history, what is one to think?

The poet John Berryman once wondered: "Is wickedness soluble in art?". One might rephrase, in a vocabulary more suitable for our politicized era: "Is wickedness soluble in good deeds?"

This paradox lies at the heart of so much of public life: individuals of dubious character and cruel deeds may redeem themselves in selfless actions. Fidelity to a personal code of morality would seem to fade in significance as the public sphere, like an enormous sun, blinds us to all else.