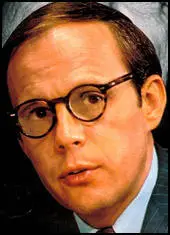

John Dean

John Wesley Dean was born in Akron, Ohio, on 14th October, 1938. He did his undergraduate studies at Colgate University. This was followed by a graduate fellowship from American University to study government and the presidency. He then entered the Georgetown University Law Center and he received his JD in 1965.

In July, 1970, Richard Nixon appointed him Counsel to the President. Other posts included Chief Minority Counsel to the Judiciary Committee of the United States House of Representatives, the Associate Director of a law reform commission, and Associate Deputy Attorney General of the United States.

On 3rd July, 1972, Frank Sturgis, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker and James W. McCord were arrested while removing electronic devices from the Democratic Party campaign offices in an apartment block called Watergate. It appeared that the men had been to wiretap the conversations of Larry O'Brien, chairman of the Democratic National Committee.

The phone number of E.Howard Hunt was found in address books of the burglars. Reporters were now able to link the break-in to the White House. Bob Woodward, a reporter working for the Washington Post was told by a friend who was employed by the government, that senior aides of President Richard Nixon, had paid the burglars to obtain information about its political opponents.

In 1972 Nixon was once again selected as the Republican presidential candidate. On 7th November, Nixon easily won the the election with 61 per cent of the popular vote. Soon after the election reports by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of the Washington Post, began to claim that some of Nixon's top officials were involved in organizing the Watergate break-in.

On February 28, 1973, FBI Director L. Patrick Gray, testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee regarding his nomination to replace J. Edgar Hoover as Director of the FBI. Sam Ervin, questioned Gray about Watergate. Gray admitted that he had discussed the FBI investigation with Dean on many occasions. Gray's nomination failed and Dean was directly linked to the Watergate cover up.

In April, 1973, Richard Nixon decided to try and force Dean, John Ehrlichman and H. R. Haldeman, to resign. Dean refused to go and was sacked. Dean issued a statement making it clear that he was unwilling to be a "scapegoat in the Watergate case". When Dean testified on 25th June, 1973 before the Senate Committee investigating Watergate, he claimed that Nixon participated in the cover-up. He also confirmed that Nixon had tape-recordings of meetings where these issues were discussed.

The Special Prosecutor now demanded access to these tape-recordings. At first Nixon refused but when the Supreme Court ruled against him and members of the Senate began calling for him to be impeached, he changed his mind. However, some tapes were missing while others contained important gaps.

Under extreme pressure, Richard Nixon supplied tapescripts of the missing tapes. It was now clear that Nixon had been involved in the cover-up and members of the Senate began to call for his impeachment. On 9th August, 1974, Nixon became the first President of the United States to resign from office.

Nixon was granted a pardon but despite Dean's full confession he was sentenced to one to four years for conspiracy to obstruct justice and to defraud the government. He served four months of his sentence. After his release Dean has written many articles on law, government, and politics. His books on Watergate include Blind Ambition: The End of the Story (1976) and Lost Honor: The Rest of the Story (1982).

In 1992 he began legal action against Gordon Liddy and Len Colodny. Dean objected to information that appeared in books by Liddy (Will) and Colodny (Silent Coup: The Removal Richard Nixon) that claimed that Dean was the mastermind of the Watergate burglaries and the true target of the break-in was to destroy information implicating him and his wife in a prostitution ring. The case was dismissed by the U.S. District Court in Baltimore after jurors could not reach a verdict. The publisher of Colodny settled a similar suit by Dean and his wife for an unknown amount of money.

Other books by Dean include The Rehnquist Choice: The Untold Story of the Nixon Appointment that Redefined the Supreme Court (2001), Unmasking Deep Throat (2002), Warren G. Harding (2004) and Worse Than Watergate: The Secret Presidency of George W. Bush (2005).

Primary and Secondary Sources

(1) Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, The Final Days (1976)

John Dean, the President's former counsel had been fired on April 30 and was now busily leaking stories all over Washington about the Watergate scandal. Some of them hinted that the President was involved in the cover-up. Dean seemed to have some record of White House misdeeds; he told Judge John Sirica that he had removed certain documents from the White House to protect them from "illegitimate destruction". Dean had put them in a safe-deposit box and given the keys to the judge. The New York Times, also citing anonymous informers, said that one of its sources "suggested that Mr. Dean may have tape-recorded some of his White House conversations".

(2) William Sullivan, The Bureau: My Thirty Years in Hoover's FBI (1979)

"I suppose the Kennedys did that kind of thing with Hoover," Dean said. I told him truthfully that the Kennedys had been so wary of Hoover that they never used the FBI at all if they could help it. Dean didn't look as if he believed me. "What about Johnson?" he asked quickly.

Once again I answered truthfully. "Compared to Lyndon Johnson," I told him, "the current administration is spartan in its use of the FBI." Dean's tongue was practically hanging out of his mouth as I talked. I couldn't tell him about every one of Johnson's illegal uses of the FBI-DeLoach was the one who could - but I could tell him enough. I told him about the FBI surveillance I'd helped to set up on Madame Chennault. I told him how Johnson had praised Hoover and the FBI for keeping tabs on Bobby Kennedy at the Democratic convention in Atlantic City by tapping Martin Luther King's phone. I told him about the behind-the-scenes wheeling and dealing done by LBJ, Abe Fortas, and Deke DeLoach after Walter Jenkins was arrested in Washington, and I told Dean that Johnson had asked the FBI to dig up derogatory information on Senator Fulbright and other Democratic senators who had attacked Johnson's policies. Of course, the FBI wasn't chartered to do that kind of work, but Hoover loved to help his friends - and those he wished were his friends.

Dean asked if I would write a confidential memo for "White House use only" detailing some examples of previous illegal political use of the FBI. He didn't tell me, and I certainly never guessed, that Dean would give the "confidential information I'd supplied to the Watergate prosecutors. I did realize, though, that I could be heading into stormy waters, so I told Dean I'd send the memo, but that I'd only write about events that I would be willing to testify to publicly. Dean readily agreed.

Then he sat back in his chair and said, "I'd like you to write a second memo after you've done that one. I'd like to pick your brains. You've been around Washington for years, and I'd like your opinion on how we should cope with the situation we have with the Plumbers."

(3) William Sullivan, memo to John Dean (1st March, 1973)

In accordance with your request I have given this problem some thought. While it is probably unnecessary I would like to say first, that the concept underlying this operation, to put it mildly, reflected atrocious judgment and the implementation of the concept was even worse in its lack of professionalism and competency.

If I had been asked about this when it happened I would have strongly recommended that the President immediately establish a non-partisan commission to look into the matter. By doing this, it would dispel most suspicion and at the same time would give you some control and some direction over the work of the commission. I think it is now too late to do this because of the plans already made by Senator Ervin. There is no longer any choice of a forum.

At this time I would suggest, for what little value they have, if any, the following:

(1) Let us take a look at the elements in the problem. We have: (i) the breaking and entering of the building; (ii) the applications of technical surveillances; and (iii) the financing. It is possible that the financing might turn out to be the most serious and harmful element in the problem. If so, then this should be given primary consideration in setting up a defense.

(2) If the assumption is valid, that the Senator Ervin inquiry will be limited and relatively brief and more of a partisan political exercise than a serious probe, then it might be well to "sit tight," issue denials where they are valid and let the storm blow over (in a manner similar to range cattle who turn their backs, stand firm and are undisturbed while the fury of the gale spends itself harmlessly!!!). However, if the contrary assumption is the valid one, and this is going to be a very real and exhaustive investigation, then "sitting tight" would be the wrong tactic and a different course of action should be taken.

(3) If it is going to be a harmful, exhaustive investigation, then I think it would be well to hire one of the best legal minds in the country. He should be a man known publicly to be of great integrity, ability and professionalism and preferably a Democrat but not one who has engaged in Democratic politics. He should not be put on a government payroll but given a retainer fee. Every effort should be made in dealing with him to show the public that he is not identified with the Administration but is acting in a dispassionate, professional manner, and that he has no ties of any kind with the Administration. I believe that this would completely eliminate the obvious disadvantages of having the lawyer enter the matter who is already on the government payroll and identified with the current administration.

(4) This man (should) have a privileged attorney-client relationship? If so, this could be an advantage.

(5) Lawyer should not have to deal with a number of individuals but only one or two men in high authority ("too many cooks spoil the broth").

(6) It is suggested that another man also be engaged to assist this lawyer. He should be a person who is extremely knowledgeable concerning the United States Senate and its members and not unacquainted with the Washington "jungle."

(7) It is suggested that when Senator Ervin commences his probe that Ron Ziegler issue a very clear, forceful and carefully constructed statement in representing the President, condemning again the Watergate activities and saying that he has instructed all concerned in the government to give their complete and willing cooperation to Senator Ervin and his colleagues.

(8) It would seem best that no issues be avoided; that each one be faced openly, briefly and without equivocation; that all possible should be done to move the inquiry along just as rapidly as possible so that it can be fully terminated in a short period of time.

(9) Naturally there will be some efforts to link the Watergate affair with the highest authorities in the White House and even to the President. Therefore, I think the main thrust of the thought given to this problem and the major positions taken should have one main purpose, expressly, to protect the President and the Office from any machinations or aspersions which would be harmful to both and a gross injustice to our Executive Branch.

(10) If worse comes to worse, bearing in mind the main objectives stated above, those involved in the Watergate affair should be considered expendable in the best interests of the country. Their culpability should be set forth in its entirety thereby directing the attention of the probers and the attention of the reading public away from the White House and to the men themselves where the blame belongs. In the position that I once occupied there were some operations necessary to carry out wither to save lives or to protect national security which were highly risky in an official sense. Those of us who carried them out did so fully understanding that if something went wrong we were expendable because values and processes far more important than we must not be damaged. I assume that the men engaged in the Watergate affair see their problem in the same prospective.

(11) One last thought - I alluded earlier to the financial element in this problem. I do not know enough about it to make any comments here. However, if it is as serious as I think it could be then those fully knowledgeable in this area should give the matter the most searching thought possible. Much more harm could be done here than in the area of the other two elements, namely breaking and entering and possessing and using electronic surveillance devices.

(12) Lastly, the above observations have been made without having read the results of the investigation. If you think I can be of any further assistance by reading in your office the investigation reports, in whole or in part, I will, of course, do so.

(4) Jeb Stuart Magruder, An American Life (1974)

Once again Dean joined us, and once again we had an inconclusive talk with Mitchell. Liddy had not specified the targets for wiretapping, but in discussion we agreed that priority should go to Larry O'Brien's office at the Democratic National Committee in the Watergate complex, to O'Brien's hotel suite in Miami Beach during the Democratic Convention, and to the campaign headquarters of whoever became the Democratic nominee for President. O'Brien had emerged in the past year as the Democrats' most effective spokesman and critic of our Administration.

Liddy still wanted to use call girls in Washington, but the others of us were skeptical and discouraged that plan. We agreed that we should have the capacity to break up hostile demonstrations, and that we needed agents who could get us information on possible disruptions at our convention. Mitchell was still concerned about the plan's price tag and told Liddy he should cut back on his costs, then we could discuss the plan again.

Mitchell, during the discussion, told Liddy that he had information that a Las Vegas newspaper publisher, Hank Greenspun, had some documents in his office that would be politically damaging to Senator Muskie. Mitchell said he would like very much to know whether these documents could be obtained. Liddy beamed and said he'd check out the situation.

So the second meeting ended with Liddy's plan still dangling. None of us was quite comfortable with it, yet all of us felt that some sort of intelligence-gathering program was needed. We knew the daily pressures from the White House for political intelligence, and I think we had a sense that this was how the game was played. During the discussion of wiretapping and break-ins, John Dean had said: "I think it is inappropriate for this to be discussed with the Attorney General. I think that in the future Gordon should discuss his plans with Jeb, then Jeb can pass them on to the Attorney General."

(5) Len Colodny and Robert Gettlin, Silent Coup: The Removal of Richard Nixon (1991)

Shortly after assuming his position, John Dean began thinking about expanding his domain, and hired former Army officer Fred F. Fielding as an assistant lawyer in the counsel's office. They became close friends. In Dean's 1976 memoir, Blind Ambition, he recounted how he explained to his new associate the way in which their careers could quickly rise: "Fred, I think we have to look at our office as a small law firm.... We have to build our practice like any other law firm. Our principal client, of course, is the president. But to convince the president we're not just the only law office in town, but the best, we've got to convince a lot of other people first." Especially Haldeman and Ehrlichman.

But how to convince them? As Dean tried to assess the situation at the White House, events soon showed him that intelligence gathering was the key to power in the Nixon White House. One of Dean's first assignments from Haldeman was to look over a startling proposal to revamp the government's domestic intelligence operations in order to neutralize radical groups such as the Black Panthers and the Weathermen.

The scheme had been the work of another of the White House's bright young stalwarts, Nixon aide Tom Charles Huston. The impetus was a meeting chaired by Nixon in the Oval Office on June 5, 1970, attended by J. Edgar Hoover, Richard Helms, and the chiefs of the NSA and the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA). The various agencies were almost at war with one another; just a few months earlier, for instance, Hoover had cut all FBI communication with the CIA. Nixon wanted the agencies to work together against the threat from the "New Left." In the aftermath of Nixon's decision in May 1970 to invade Cambodia, and the killings of several students at Kent State University, colleges all over the country were again being rocked by riots and demonstrations as they had been in the last year of Lyndon Johnson's presidency, and for the same reason-young people were objecting to the president's war policies. In Nixon's view, the threat was grave and must be attacked; therefore the agencies must find some way to bury their differences and concentrate on the true enemy. Huston was assigned to help Hoover and the intelligence chiefs clear obstacles to their working jointly on these matters.

In early July, Huston sent a long analysis to the president, endorsed by Hoover and the other intelligence agency directors, on how to enhance cooperation. To this memo Huston added his own secret one that became known as the "Huston Plan." It called for six activities, some of which were clearly illegal. They included electronic surveillance of persons and groups "who pose a major threat to internal security"; monitoring of American citizens by international communications facilities; the relaxation of restrictions on the covert opening of mail by federal agents; surreptitious entries and burglaries to gain information on the groups; the recruitment of more campus informants; and, to ensure that the objectives were carried out and that intelligence continued to be gathered, the formation of a new interagency group consisting of the agencies at the June 5 meeting and military counter-intelligence agencies. Nixon endorsed these measures in the Huston Plan on July 14, 1970, because, as he put it in his memoir, "I felt they were necessary and justified by the violence we faced."

The secret plan angered J. Edgar Hoover, not because he objected to coming down hard on dissidents, but, rather, because he felt that any new interagency group would encroach on the turf of the FBI and because he was concerned about the negative public reaction should any of the activities be exposed. On July 27, the day Dean began work at the White House, Hoover took the unusual step of venturing out of his own domain to visit his nominal superior, Attorney General John Mitchell. As Hoover learned, Mitchell did not know anything about the Huston Plan at the time. "I was kept in the dark until I found out about it from Hoover," Mitchell later told us. But as soon as he was apprised of the plan, Mitchell agreed with Hoover that it must be stopped-not for Hoover's reasons, but because it contained clearly unconstitutional elements-and immediately visited Nixon and told him it could not go forward. In testament to Mitchell's arguments and good sense, Nixon canceled the plan shortly thereafter and Huston was relieved of his responsibilities in the area of domestic intelligence.

Coordination of official domestic intelligence from various federal agencies concerning anti-war activists and other "radicals" was then handed to the new White House counsel, John Dean, along with a copy of the rejected Huston Plan. But it seemed that the president was still not satisfied with the quality of domestic intelligence, because in August and September Haldeman pushed Dean to try and find a way around the Hoover road-block. In pursuit of a solution, on September 17, 1970, Dean went to see his old boss, John Mitchell. Hours earlier, Mitchell had lunched with Director Helms and other senior CIA officials who had all agreed that the FBI wasn't doing a very good job of collecting domestic intelligence.

Dean and Mitchell spoke, and the next day Dean prepared a memo to Mitchell with several suggestions: "There should be a new committee set up, an interagency group to evaluate the government's domestic intelligence product, and it should have "operational" responsibilities as well. Both men, Dean's memo said, had agreed that "it would be inappropriate to have any blanket removal of restrictions" such as had been proposed in the Huston Plan; instead, Dean suggested that "The most appropriate procedure would be to decide on the type of intelligence we need, based on an assessment of the recommendations of this unit, and then to proceed to remove the restraints as necessary to obtain such intelligence."

Dean's plan languished and was never put into operation. Years later, in the spring of 1973, when Dean was talking to federal prosecutors and preparing to appear before the Senate committee investigating Watergate, he gave a copy of the Huston Plan to Federal Judge John J. Sirica, who turned it over to the Senate committee. Dean's action helped to establish his bona fides as the accuser of the president and was the cause of much alarm. In his testimony and writings thereafter, Dean suggested that he had always been nervous about the Huston Plan and that he had tried to get around it, and as a last resort had gotten John Mitchell to kill the revised version. In an interview, Dean told us, "I looked at that goddamn Tom Huston report," went to Mitchell and said, "General, I find it pretty spooky." But as the September 18, 1970, memo to Mitchell shows, Dean actually embraced rather than rejected the removal of "restraints as necessary to obtain" intelligence.

A small matter? A minor divergence between two versions of the same incident? As will become clear as this inquiry continues, Dean's attempt to gloss over the actual disposition of the Huston Plan was a first sign of the construction of a grand edifice of deceit.

(6) Taped conversation between Richard Nixon and John Dean (21st March, 1973)

John Dean: We have a cancer within, close to the Presidency, that is growing. Basically it is because we are being blackmailed.

Richard Nixon: How much money do you need?

John Dean: I would say these people are going to cost a million dollars over the next two years.

Richard Nixon: You could get a million dollars. You could get it in cash. I know where it could be gotton.

(7) John Dean, statement (20th April, 1973)

To date, I have refrained from making any public comment whatsoever about the Watergate case. Some may hope or think that I will become a scapegoat in the Watergate case. Anyone who believes this does not know me, know the true facts, nor understands our system of justice.

(8) Taped conversation between Richard Nixon and John Dean (28th February, 1973)

John Dean: Kalmbach raised some cash.

Richard Nixon: They put that under the cover of a Cuban committee, I suppose?

John Dean: Well, they had a Cuban committee and they - had-some of it was given to Hunt's lawyer, who in turn passed it out. You know, when Hunt's wife was flying to Chicago with $10,000 she was actually, I understand after the fact now, was going to pass that money to one of the Cubans - to meet him in Chicago and pass it to, somebody there.... You've got then, an awful lot of the principals involved who know. Some people's wives know. Mrs. Hunt was the savviest woman in the world. She had the whole picture together.

Richard Nixon: Did she?

John Dean: Yes. Apparently, she was the pillar of strength in that family before the death.

Richard Nixon: Great sadness. As a matter of fact there was discussion with somebody about Hunt's problem on account of his wife and I said, of course commutation could be considered on the basis of his wife's death, and that is the only conversation I ever had in that light.

John Dean: Right. So that is it. That is the extent of the knowledge

(9) John Dean, Blind Ambition: The End of the Story (1976)

Chuck Colson said... "I tell you, John... I turned into something of a CIA freak on Watergate for a while, you know, and I still think there's something there. I haven't figured out how it all adds up, but I know one thing: the people with CIA connections sure did better than the rest of us. Paul O'Brien's an old CIA man, and he walked. David Young was Kissinger's CIA liaison, and he ran off to England when he got immunity. Bennett worked for the CIA, and he ran back to Hughes. And Dick Helms skated through the whole thing somehow. Maybe those guys just knew how to play the game better than we did."

(10) William Colby, Honorable Men: My Life in the CIA (1978)

A footnote to this incident is the fact that John Dean obviously did recognize the photographs and their significance long before the Ellsberg trial. For early - in 1973, somewhat nervously, he asked that all of CIA's memos (obviously including the photographs) be returned to the CIA from the FBI, leaving a card in the FBI's file that this had been done. I recommended that we agree to no such thing since I saw no legitimate rationale for doing so, although I had no suspicion what might be behind Dean's request at the time. We reacted the same way as we reacted when Dean approached Walters shortly after the Watergate arrests with the idea that the CIA provide bail for the arrested Watergate burglars. Walters turned that one down flatly, pointing out that this would he impossible, since the Agency had no funds available for such an activity and if it made some available for any such action it would have to report the fact to Congressional committees. The strategy was to ensure that CIA avoid getting involved in Watergate or any other improper activity, but to do this without taking, a hostile position toward the White House, explaining why we could not do something and not probing into whatever it might be doing - just staying out.

But this cautious, "distancing " strategy proved to he a double-edged sword, cutting, the Agency in two ways. On the one hand, the CIA was perceived as withholding evidence as long as it possibly could - then revealing it (grudgingly and only what had been specifically asked for and not a whit more. This clearly generated further distrust and suspicion, and reinforced the hostile questions being asked about the Agency's good faith and its use-or abuse of its institutionalized secrecy. On the other hand, each disclosure wrung or leaked from the reluctant Agency during this period caused a greater sensation than it would have done if the information had been volunteered. Moreover, each such disclosure fed the belief that more sinister material was still being withheld, and the White House launched rumors that CIA was the real culprit in the whole affair gained much currency. The over-all result in the long run was to tarnish the CIA's reputation even further.

In the short run, to be sure, Helms's strategy did have the effect of preventing the CIA's tangential connection with the plumbers in 1971 from being blown into sensational proportions by the media before they could be presented in their true context. And more to the point, it also prevented the Agency from becoming involved in the Watergate cover up, of being used by the Nixon White House to escape punishment for its crimes. Indeed, in this respect it worked so well that the Washington Post, surely among the most aggressively investigative of all the media on Watergate, noted in an editorial that the CIA "was the only agency in town that said 'No.' "

Dick Helms paid the price for that "No." In early December 1972, he was invited to Camp David for a meeting with the President. The belief at Langley was that he was being called to discuss the CIA budget, which at the time was under some debate with the Office of Management and Budget. So I arranged a careful briefing on the arguments on our side before he went. But it turned out to be a waste of time. What happened at Camp David had nothing to do with the budget. It had to do with Helms's careful distancing of the Agency from Watergate, his refusal to allow it to be used in the cover-up. And for that Nixon fired him as DCI, sent him packing to Iran as ambassador and named James Schlesinger as the Agency's new chief.

(11) Laurence Stern and Haynes Johnson, Washington Post (1st May, 1973)

President Nixon, after accepting the resignations of four of his closest aides, told the American people last night that he accepted full responsibility for the actions of his subordinates in the Watergate scandal.

"There can be no whitewash at the White House," Mr. Nixon declared in a special television address to the nation. He pledged to take steps to purge the American political system of the kind of abuses that emerged in the Watergate affair.

The President took his case to the country some 10 hours after announcing that he had accepted the resignations of his chief White House advisers, H.R. Haldeman and John D. Ehrlichman, along with Attorney General Richard G. Kleindienst.

He also announced that he had fired his counsel, John W. Dean III, who was by the ironies of the political process a casualty of the very scandal the President had charged him to investigate.

The dramatic news of the dismantling of the White House command staff that served Mr. Nixon through his first four years in the presidency was the most devastating impact that the Watergate scandal has yet made on the administration.

The President immediately set into motion a major reshuffling of top administration personnel to fill the slots of the Watergate causalities. Defense Secretary Elliott L. Richardson was appointed to replace Kleindienst and to take over responsibility for "uncovering the whole truth" about the Watergate scandal.

He said last night that he was giving Richardson "absolute authority" in handling the Watergate investigation - including the authority to appoint a special prosecutor to supervise the government's case.

As temporary successor to Dean, the President chose his special consultant, Leonard Garment. Mr. Nixon said Garment "will represent the White House in all matters relating to the Watergate investigation and will report directly to me."

Last night Gordon Strachan, whose name has been linked to the Watergate case, resigned as general counsel to the United States Information Agency. The USIA said the former aide to Haldeman resigned "after learning that persons with whom he had worked closely at the White House had submitted their resignations. . ."

The immediate reaction to yesterday's White House announcement was a mixture of relief, especially among congressional Republicans, at the prospect of internal housecleaning. But there was also some dismay at the President's failure to appoint a special prosecutor for the Watergate inquiry...

Besides the resignations announced yesterday, at least five other high administration or campaign officials have quit in the wake of revelations about the Watergate: Mitchell, presidential appointments secretary Dwight Chapin, special counsel to the president Charles W. Colson, deputy campaign director Jeb Stuart Magruder and acting FBI Director L. Patrick Gray III.

The massive shake-up of the White House command and the ensuing personnel reshuffling threw the administration into a state of disarray if not temporary immobility.

It threatens the federal government's largest single enterprise, the pentagon, with a state of leaderlessness with Richardson's new assignment. In the White House, Haldeman and Ehrlichman had been the twin pillars of a management system in which they had been regarded as indispensable to the President. Haldeman, particularly, was the ultimate traffic controller and organizer of the flow of presidential business.

(12) Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, Washington Post (3rd June, 1973)

Former presidential counsel John W. Dean III has told Senate investigators and federal prosecutors that the discussed aspects of the Watergate cover-up with President Nixon or in Mr. Nixon's presence on at least 35 occasions between January and April of this year, according to reliable sources.

Dean plans to testify under oath at the Senate's Watergate hearings, regardless of whether he is granted full immunity from prosecution, and he will allege that President Nixon was deeply involved in the cover-up, the sources said.

Dean has told investigators that Mr. Nixon had prior knowledge of payments used to buy the silence of the Watergate conspirators and of offers of executive clemency extended in his name, the sources said.

Dean has little or no documentary evidence to support his charges against the President and most of his allegations are based on his own recollection of purported conversations with Mr. Nixon, the sources said.

Dean, the sources reported, claims that Mr. Nixon's former principal deputies, H.R. Haldeman and John D. Ehrlichman, were also present at many meetings in which the cover-up was discussed in the presence of the President.

Dean's statements to investigators have the effect of pitting him along against the President and Haldeman and Ehrlichman, all of whom denied involvement in the Watergate bugging or any subsequent cover-up.

The White House, as well as Haldeman and Ehrlichman, have pictured Dean as the principal figure in the Watergate cover-up. Justice Department sources say there is ample evidence to indict Dean in the case and that the former presidential counsel appears to have been more than just a reluctant participant in the Watergate cover-up.

In contrast, Dean and his associates have pictured the former counsel as a loyal White House aide who was only following orders in the Watergate, cover-up and who, as time went on, agonized over what Watergate was doing to Mr. Nixon.

Dean is still seeking full immunity from prosecution, seeking to stay out of jail and hoping to keep his law license. But Senate and Justice Department sources said Dean's charges against the President are unrelated to the question of whether he is granted such immunity and thus are not necessary self-serving.

One of the strongest charges against Mr. Nixon that Dean has made to investigators refers to a meeting Dean said he had with Mr. Nixon shortly before the sentencing of the seven Watergate defendants March 23, Dean said that Mr. Nixon asked him how much the defendants would have to be paid to insure their continued silence, in addition to $460,000 that had already been paid, the sources said.

Dean, the sources reported, maintains that he told Mr. Nixon the additional cost would be about $1 million, and Dean also claims the President replied there would be no problem in paying that amount.

(13) John Dean, Lost Honor: The Rest of the Story (1982)

Much of the information that Deep Throat knew was known by many people. While it is impossible to know who might have whispered secrets to whom, thus broadening the circle of knowledge, working logically two particular bits of information that were given to Woodward by his friend easily point to Al Haig.

On March 5, 1973, Time magazine broke a story that the White House had wiretapped newsmen and White House aides in an effort to track down leaks. The White House denied the story was true, although it was true. Time had cracked this case, but they could not learn from their sources in the FBI and Justice Department who had been bugged. The records of the taps had been removed by Bill Sullivan, and passed by Bob Mardian to the White House. When the Time story broke, the records were in John Ehrlichman's safe.

When Woodward met with his friend in late February, shortly before Pat Gray's confirmation hearings, Deep Throat was able to tell Bob that Gray had been aware of these wiretaps and that the work was done by an "out-of-channels vigilante squad." This last piece of information could have been a deliberate effort to mislead Woodward, since it was not true. Deep Throat also gave Woodward the names of two people who had been tapped: "Hedrick Smith and Neil Sheehan of The New York Times." It is the revelation of these names that is the extraordinary information.

I found it interesting that, first, Deep Throat could state flatly that Gray knew about the taps, when he was also saying this was not an FBI operation, and when the Watergate special prosecutor would be unable to prove that Gray knew after an intense investigation with the full resources of the FBI, Justice Department, and several years of digging. Second, the only people who knew the names of those who had been tapped at the time the information was given to Woodward were Richard Nixon, Henry Kissinger, John Ehrlichman, John Mitchell, Bob Mardian, a very small group in the FBI, Bill Sullivan, Mark Felt, and the man who gave the FBI the names - Al Haig.

When you add to this the scarcely known secret that was given to Woodward about the "deliberate erasures" on the court-subpoenaed tape, Haig passes another test that uniquely qualifies him as the most likely person to have been Woodward's friend.

(14) Len Colodny and Robert Gettlin, Silent Coup: The Removal of Richard Nixon (1991)

We have earlier drawn many sections from Dean's testimony to demonstrate what was true and what was false about it, so we will not recapitulate here those five days of Dean that gripped the television audience near the end of June 1973. However, some comments on the testimony are needed.

Dean's testimony was extremely detailed because it had to be; his picture had to be complete to be thoroughly convincing. And Dean was in perfect position to draw that picture because he had known all of what had gone on during the planning for the break-in and the cover-up; he alone had all the information.

Dean had cut his hair, donned glasses, and wore only conservative attire when he testified. Behind him sat Maureen, often the subject of photographers and of the television cameras as she sat, in conservative clothing, poised, good-looking, blond, her hair piled atop her head. As her husband of eight months poured out his story she appeared to pay attention but not to betray any emotion.

In his testimony Dean implicated Mitchell-reluctantly, it seemed-and more readily aimed allegations at Ehrlichman, Haldeman, and at the president. He went easy on Magruder and Strachan, only bringing them in when he had to, and all the while being careful lest he anger them unduly and provoke them to the sorts of detailed recollections of what had happened that would have revealed to the Senate committee Dean's own complicity and role as central instigator, and given his interlocutors reason to doubt his story.

The committee bought Dean, lock, stock, and barrel, precisely because he was an arrow that pointed upward, in the direction they chose to look, some members reluctantly, some eagerly, but all firmly casting their eyes toward a single destination: the president. "What did the President know, and when did he know it?" Senator Howard Baker asked. Baker did not inquire as to the president's sources of information, or if those sources lied to Nixon or tricked him into undertaking illegal cover-up actions. Later on, in their own testimony, all that Haldeman, Ehrlichman, and Mitchell seemed to be able to offer to the committee were denials that rang hollow because they were not as densely detailed as Dean's accusations. They did have documents, but Mitchell's logs were ignored, and the notes of Haldeman and Ehrlichman seemed self-serving. Moreover, the committee apparently ignored Strachan's offer of documents that showed that Dean handled political intelligence at the White House.

There were many holes in Dean's story, and logical inconsistencies. Few of these holes and inconsistencies were closely scrutinized, because it seemed inconceivable to the senators and their staff that the arrow should possibly be pointing at Dean and not away from him. In effect, Dean had a free ride.

(15) Scott Rosenberg, interview with John Dean, Salon Magazine (17th June, 2002)

Scott Rosenberg: How long have you been searching for Deep Throat?

John Dean: Throat first surfaced in 1974 when Woodward and Bernstein published "All the President's Men." When I first read the book, I thought that Woodward's friend and source was probably a composite. Some information appeared to come from the White House, some from the FBI, some from the Committee to Re-elect the President, known as CREEP or CRP. But I really didn't start seriously searching until around 1978.

Scott Rosenberg: When did you decide Throat was not a composite, and why?

John Dean: Actually, it was Bob Woodward who persuaded me. I happened to state publicly in a speech, not long after his book came out, that I thought Throat was a composite, and that was picked up by the Washington Post. I had first met and had dinner with Bob not long before the speech, and when he sent me a message assuring me it was not a composite, I believed him.

Scott Rosenberg: So you take Woodward at his word about all this?

John Dean: Absolutely. Over the past 30 years I've gotten to know Bob, and everything I know about him reeks of honesty and sincerity. I don't think he has ever lost his Midwestern values, and I can't imagine him playing games. He has staked his professional reputation on his reporting, and while other journalists carp, and complain about his use of unidentified sources, I believe he reports as accurately and candidly as humanly possible.

Scott Rosenberg: In your new book, "Unmasking Deep Throat," you write that you have relied on Woodward's honesty in figuring out who might be Deep Throat. Did you find anything in your research that might change your mind?

John Dean: To the contrary. I was able to locate a copy of the unedited manuscript of "All The President's Men," which runs about 900 pages. It is probably twice as long as the published book ended up. Not only did I find clues about Deep Throat that for one reason or another did not make it into the book, I found many examples of both Woodward's and Carl Bernstein's candor -- like explaining who had undertaken various activities, and how it took time to develop what has now become their lifelong friendship. For anyone to not accept Woodward's information about Throat, in the manuscript, in the book and in his statements over the past two and half decades, would make searching for him futile. If Woodward has not been honest, it would make Deep Throat a hoax. I don't believe that is the case, and few have peeled apart his work like I have.

John Dean: Scott Rosenberg: Is it important to know Deep Throat's identity? Isn't looking for him a little like being one of Richard Nixon's infamous Plumbers, the guys who hunted for leaks?

John Dean: Fair question. Some of my former colleagues, like Leonard Garment, believe that Deep Throat has had a profound impact on American politics. Other knowledgeable people, like former Washington Post editor Barry Sussman, who had editorial supervision over most of Woodward's and Bernstein's Watergate reporting, feel that Deep Throat's information was so insubstantial that he added little to the Post's Watergate coverage. Both are correct. Deep Throat is important because he gave the managing editor of the Post, Ben Bradlee, the confidence to keep publishing one story after another about campaign improprieties that high officials at the White House and CRP kept denying. Throat also changed journalism - he gave the unidentified source credibility.

(16) Timothy Noah, Salon and John Dean's Deep Throat Candidate Revealed! (1st May, 2002)

John Dean and Salon magazine will celebrate the 30th anniversary of the June 17 Watergate break-in by publishing an eBook called The Deep Throat Brief. In it, according to the San Francisco Chronicle's Leah Garchik and the Associated Press, Dean will attempt to unveil Deep Throat, the anonymous source who, according to Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein's All the President's Men, helped the Washington Post crack the Watergate case. (The "Deep Throat" nickname derived from the pornographic movie of that title, whose star, Linda "Lovelace" Boreman, died last week in a car crash. Unlike today, during the 1970s it was possible for a joke about fellatio to be incorporated into mainstream politico-journalistic discourse.)

Chatterbox will of course dig into Dean's book when it comes out to assess his evidence. But the precedent for former Nixon administration officials claiming to solve the Deep Throat mystery is not encouraging. Two years ago, former Nixon White House counsel Leonard Garment published an otherwise engaging and insightful memoir called In Search of Deep Throat that made the mistake of identifying Republican strategist John Sears as Deep Throat. The ink was barely dry before Woodward and Bernstein, whom Garment had neglected to consult on this hypothesis, stated publicly that Sears wasn't Deep Throat, whereupon Garment started flinging nasty and unfounded accusations their way. (See "Len Garment Kills the Messenger.") Dean himself has previously identified two separate individuals as Deep Throat. In 1975, he argued that it was Watergate prosecutor Earl Silbert, and in 1982, he fingered Nixon chief of staff Al Haig. This time, Dean will likely identify as Deep Throat someone who worked under domestic affairs adviser John Ehrlichman. Chatterbox deduces this from an article by John Bebow in the March American Journalism Review that says Dean has been working closely with William Gaines, a Pulitzer Prize-winning former reporter for the Chicago Tribune who now teaches at the University of Illinois. Gaines has been assembling a Deep Throat database by cross-referencing newspaper stories, government documents, old D.C. phone books, biographies, etc. "Ehrlichman's office comes up every time," Gaines told AJR, though he added that he didn't consider Ehrlichman himself a suspect. (Ehrlichman died three years ago, so there would be no reason for Woodward and Bernstein to keep his identity secret.)

In the absence of additional evidence, Chatterbox continues to believe that Deep Throat didn't work at the White House at all - that instead, Deep Throat worked for the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which, in the immediate aftermath of J. Edgar Hoover's death in May 1972, was caught up in a power struggle with the Nixon White House. James Mann, who worked closely with Woodward at the Post during this period, recalls Woodward talking frequently about "my friend at the FBI." Mann combined this with lots of other evidence in a 1992 Atlantic piece that, 10 years later, remains the definitive word on the subject. The likeliest person at the FBI to have been Deep Throat was W. Mark Felt, the deputy associate director (that is, No. 3 guy), who wanted to be named Hoover's successor but wasn't. Felt is now in his late 80s and living in California. He has repeatedly denied (including to Chatterbox) that he was Deep Throat. But Bernstein's ex-wife, Nora Ephron, has long believed that Felt was Deep Throat. So did Nixon - to whom this question was no mere intellectual exercise. Felt is the default assumption of any serious Deep Throat scholar, and has been for nearly 30 years. To unseat him will require a lot more evidence than Chatterbox guesses Dean to possess.