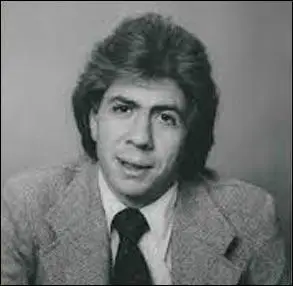

Carl Bernstein

Carl Bernstein was born in Washington on 14th February, 1944. Both his parents, Al and Sylvia Bernstein, were active trade unionists and members of the American Communist Party. As a result of the Red Scare they were both blacklisted and after the execution of Julius Rosenberg and Ethel Rosenberg, the family went into hiding as they feared this was the beginning of a wave of persecution of Jews.

Bernstein became a journalist and in 1966 began working for the Washington Post. However, his articles did not find favour with his editor, Ben Bradlee. According to Deborah Davis, the author of Katharine the Great (1979): Carl Bernstein was the "house misfit, who was talented enough to be a new journalist and wrote in the dramatic prose that Bradlee enjoyed, but whose insistent pieces on ethnic neighborhoods, alternative politics (the missing link between the war and the counterculture), the movement as a movement, not a fashion, were a continual source of annoyance to him. Bernstein was not part of Bradlee's scheme; he killed a good number of his stories, and he cursed the guild for standing in the way of firing him."

On 3rd July, 1972, Frank Sturgis, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker and James W. McCord were arrested while removing electronic devices from the Democratic Party campaign offices in an apartment block called Watergate. It appeared that the men had been to wiretap the conversations of Larry O'Brien, chairman of the Democratic National Committee.

The phone number of E.Howard Hunt was found in address books of the burglars. Reporters were now able to link the break-in to the White House. Bernstein and fellow journalist, Bob Woodward, began working on the case. Woodward had a government source who was given the name "Deep Throat". He informed Woodward that senior aides of President Richard Nixon, had paid the burglars to obtain information about its political opponents.

Bernstein and Woodward discovered that in 1972 Frederick LaRue worked with John Mitchell on Nixon's re-election committee. On 20th March, LaRue attended a meeting of the committee where it was agreed to spend $250,000 "intelligence gathering" operation against the Democratic Party. This included the decision to plant electronic devices from the Democratic campaign offices in Watergate.

Frederick LaRue now decided that it would be necessary to pay the large sums of money to secure the the silence of the burglars. LaRue raised $300,000 in hush money. Tony Ulasewicz, a former New York policeman, was given the task of arranging the payments.

In January, 1973, Frank Sturgis, E.Howard Hunt, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker, Gordon Liddy and James W. McCord were convicted of conspiracy, burglary and wiretapping.

Nixon continued to insist that he knew nothing about the case or the payment of "hush-money" to the burglars. However, in April 1973, Nixon forced two of his principal advisers H. R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, to resign. A third adviser, John Dean, refused to go and was sacked.

On 20th April, Dean issued a statement making it clear that he was unwilling to be a "scapegoat in the Watergate case". When Dean testified on 25th June, 1973 before the Senate Committee investigating Watergate, he claimed that Richard Nixon participated in the cover-up. He also confirmed that Nixon had tape-recordings of meetings where these issues were discussed.

The Special Prosecutor now demanded access to these tape-recordings. At first Nixon refused but when the Supreme Court ruled against him and members of the Senate began calling for him to be impeached, he changed his mind. However, some tapes were missing while others contained important gaps.

Under extreme pressure, Nixon supplied tapescripts of the missing tapes. It was now clear that Nixon had been involved in the cover-up and members of the Senate began to call for his impeachment. On 9th August, 1974, Richard Nixon became the first President of the United States to resign from office. Nixon was granted a pardon but other members of his staff involved in helping in his deception were imprisoned.

Bernstein, Bob Woodward, Ben Bradlee and the Washington Post received a great deal of credit for exposing the Watergate Scandal and in 1973 the newspaper was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for journalism. Bernstein and Woodward also wrote two books about Watergate: All the President's Men (1975) and The Final Days (1976).

Bernstein left the Washington Post in 1976 to work as a Washington Bureau Chief and eventually as senior correspondent for ABC-TV. While at ABC, he uncovered a secret agreement between the United States, Egypt, China and Pakistan to supply arms to the Mujahadeen rebels in Afghanistan against the Soviets.

In 1977 Bernstein wrote an article about Operation Mockingbird, a CIA covert operation to control the mass media. He also contributed articles to several major publications including Time Magazine, The New Republic, New York Times, Newsweek and the Rolling Stone Magazine.

Books by Bernstein include Loyalties: A Son's Memoir (1989) an account of his parents' encounter with McCarthyism and His Holiness - John Paul II and the Hidden History of Our Time (1998).

Carl Bernstein is contributing editor for Vanity Fair magazine and in 2007 published A Woman in Charge, a biography of Hillary Rodham Clinton.

Primary Sources

(1) Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, Washington Post (19th June, 1972)

One of the five men arrested early Saturday in the attempt to bug the Democratic National Committee headquarters is the salaried security coordinator for President Nixon's reelection committee.

The suspect, former CIA employee James W. McCord Jr., 53, also holds a separate contract to provide security services to the Republican National Committee, GOP national chairman Bob Dole said yesterday.

Former Attorney General John N. Mitchell, head of the Committee for the Re-Election of the President, said yesterday McCord was employed to help install that committee's own security system.

In a statement issued in Los Angeles, Mitchell said McCord and the other four men arrested at Democratic headquarters Saturday "were not operating either in our behalf or with our consent" in the alleged bugging attempt.

Dole issued a similar statement, adding that "we deplore action of this kind in or out of politics." An aide to Dole said he was unsure at this time exactly what security services McCord was hired to perform by the National Committee.

Police sources said last night that they were seeking a sixth man in connection with the attempted bugging. The sources would give no other details.

Other sources close to the investigation said yesterday that there still was no explanation as to why the five suspects might have attempted to bug Democratic headquarters in the Watergate at 2600 Virginia Ave., NW, or if they were working for other individuals or organizations..

"We're baffled at this point.... the mystery deepens," a high Democratic party source said.

Democratic National Committee Chairman Lawrence F. O'Brien said the "bugging incident... raised the ugliest questions about the integrity of the political process that I have encountered in a quarter century.

"No mere statement of innocence by Mr. Nixon's campaign manager will dispel these questions."

The Democratic presidential candidates were not available for comment yesterday.

O'Brien, in his statement, called on Attorney General Richard G. Kleindienst to order an immediate, "searching professional investigation" of the entire matter by the FBI.

A spokesman for Kleindienst said yesterday. "The FBI is already investigating. . . . Their investigative report will be turned over to the criminal division for appropriate action."

The White House did not comment.

McCord, 53, retired from the Central Intelligence Agency in 1970 after 19 years of service and established his own "security consulting firm," McCord Associates, at 414 Hungerford Drive, Rockville. He lives at 7 Winder Ct., Rockville.

McCord is an active Baptist and colonel in the Air Force Reserve, according to neighbors and friends.

In addition to McCord, the other four suspects, all Miami residents, have been identified as: Frank Sturgis (also known as Frank Florini), an American who served in Fidel Castro's revolutionary army and later trained a guerrilla force of anti-Castro exiles; Eugenio R. Martinez, a real estate agent and notary public who is active in anti-Castro activities in Miami; Virgilio R. Gonzales, a locksmith; and Bernard L. Barker, a native of Havana said by exiles to have worked on and off for the CIA since the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961.

All five suspects gave the police false names after being arrested Saturday. McCord also told his attorney that his name is Edward Martin, the attorney said.

Sources in Miami said yesterday that at least one of the suspects - Sturgis - was attempting to organize Cubans in Miami to demonstrate at the Democratic National Convention there next month.

The five suspects, well-dressed, wearing rubber surgical gloves and unarmed, were arrested about 2:30 a.m. Saturday when they were surprised by Metropolitan police inside the 29-office suite of the Democratic headquarters on the sixth floor of the Watergate.

The suspects had extensive photographic equipment and some electronic surveillance instruments capable of intercepting both regular conversation and telephone communication.

Police also said that two ceiling panels near party chairman O'Brien's office had been removed in such a way as to make it possible to slip in a bugging device.

McCord was being held in D.C. jail on $30,000 bond yesterday. The other four were being held there on $50,000 bond. All are charged with attempted burglary and attempted interception of telephone and other conversations.

McCord was hired as "security coordinator" of the Committee for the Re-election of the President on Jan. 1, according to Powell Moore, the Nixon committee's director of press and information.

Moore said McCord's contract called for a "take-home salary of $1,200 per month and that the ex-CIA employee was assigned an office in the committee's headquarters at 1701 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W.

Within the last one or two weeks, Moore said, McCord made a trip to Miami beach -- where both the Republican and Democratic National Conventions will be held. The purpose of the trip, Moore said, was "to establish security at the hotel where the Nixon Committee will be staying."

In addition to McCord's monthly salary, he and his firm were paid a total of $2,836 by the Nixon Committee for the purchase and rental of television and other security equipment, according to Moore.

Moore said that he did not know exactly who on the committee staff hired McCord, adding that it "definitely wasn't John Mitchell." According to Moore, McCord has never worked in any previous Nixon election campaigns "because he didn't leave the CIA until two years ago, so it would have been impossible." As of late yesterday, Moore said. McCord was still on the Reelection Committee payroll.

In his statement from Los Angeles, former Attorney General Mitchell said he was "surprised and dismayed" at reports of McCord's arrest.

"The person involved is the proprietor of a private security agency who was employed by our committee months ago to assist with the installation of our security system," said Mitchell. "He has, as we understand it, a number of business clients and interests and we have no knowledge of these relationships."

Referring to the alleged attempt to bug the opposition's headquarters, Mitchell said: "There is no place in our campaign, or in the electoral process, for this type of activity and we will not permit it nor condone it."

About two hours after Mitchell issued his statement, GOP National Chairman Dole said, "I understand that Jim McCord... is the owner of the firm with which the Republican National Committee contracts for security services . . . if our understanding of the facts is accurate, added Dole, "we will of course discontinue our relationship with the firm."

Tom Wilck, deputy chairman of communications for the GOP National Committee, said late yesterday that Republican officials still were checking to find out when McCord was hired, how much he was paid and exactly what his responsibilities were.

McCord lives with his wife in a two-story $45,000 house in Rockville.

After being contacted by The Washington Post yesterday, Harlan A. Westrell, who said he was a friend of McCord's, gave the following background on McCord:

He is from Texas, where he and his wife graduated from Baylor University. They have three children, a son who is in his third year at the Air Force Academy, and two daughters.

The McCords have been active in the First Baptist Church of Washington.

Other neighbors said that McCord is a colonel in the Air Force Reserve, and also has taught courses in security at Montgomery Community College. This could not be confirmed yesterday.

McCord's previous employment by the CIA was confirmed by the intelligence agency, but a spokesman there said further data about McCord was not available yesterday.

In Miami, Washington Post Staff Writer Kirk Schartenberg reported that two of the other suspects - Sturgis and Barker - are well known among Cuban exiles there. Both are known to have had extensive contracts with the Central Intelligence Agency, exile sources reported, and Barker was closely associated with Frank Bender, the CIA operative who recruited many members of Brigade 2506, the Bay of Pigs invasion force.

Barker, 55, and Sturgis, 37, reportedly showed up uninvited at a Cuban exile meeting in May and claimed to represent an anticommunist organization of refugees from "captive nations." The purpose of the meeting, at which both men reportedly spoke, was to plan a Miami demonstration in support of President Nixon's decision to mine the harbor of Haiphong.

Barker, a native of Havana who lived both in the U.S. and Cuba during his youth, is a US Army veteran who was imprisoned in a German POW camp during the World War II. He later served in the Cuban Buro de Investigationes - secret police - under Fidel Castro and fled to Miami in 1959. He reportedly was one of the principal leaders of the Cuban Revolutionary Council, the exile organization established with CIA help to organize the Bay of Pigs Invasion.

Sturgis, an American soldier of fortune who joined Castro in the hills of Oriente Province in 1958, left Cuba in 1959 with his close friend, Pedro Diaz Lanz, then chief of the Cuban air force. Diaz Lanz, once active in Cuban exile activities in Miami, more recently has been reported involved in such right-wing movements as the John Birch Society and the Rev. Billy James Hargis' Christian Crusade.

Sturgis, more commonly known as Frank Florini, lost his American citizenship in 1960 for serving in a foreign military force - Castro's army - but, with the aid of then-Florida Sen. George Smathers, regained it.

(2) Richard Nixon, The Memoirs of Richard Nixon (1978)

My reaction to the Watergate break-in was completely pragmatic. If it was also cynical, it was a cynicism born of experience. I had been in politics too long, and seen everything from dirty tricks to vote fraud. I could not muster much moral outrage over a political bugging.

Larry O'Brien might affect astonishment and horror, but he knew as well as I did that political bugging had been around nearly since the invention of the wiretap. As recently as 1970 a former member of Adlai Stevenson's campaign staff had publicly stated that he had tapped the Kennedy organization's phone lines at the 1960 Democratic convention Lyndon Johnson felt that the Kennedys had had him tapped - Barry Goldwater said that his 1964 campaign had been bugged; and Edgar Hoover told me that in 1968 Johnson had ordered my campaign plane bugged. Nor was the practice confined to politicians. In 1969 an NBC producer was fined and given a suspended sentence for planting a concealed microphone at a closed meeting of the 1968 Democratic platform committee. Bugging experts told the Washington Post right after the Watergate break-in that the practice "has not been uncommon in elections past... it is particularly common for candidates of the same party to bug one another."

(3) Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, All the President's Men (1975)

Woodward had a source in the Executive Branch who had access to information at CRP as well as at the White House. His identity was unknown to anyone else. He could be contacted only on very important occasions. Woodward had promised he would never identify him or his position to anyone. Further, he, had agreed never to quote the man, even as an anonymous source. Their discussions would be only to confirm information that had been obtained elsewhere and to add some perspective.

In newspaper terminology, this meant the discussions were on "deep background." Woodward explained the arrangement to managing editor Howard Simons one day. He had taken to calling the source "my friend," but Simons dubbed him "Deep Throat," the title of a celebrated pornographic movie. The name stuck.

At first Woodward and Deep Throat had talked by telephone, but as the tensions of Watergate increased, Deep Throat's nervousness grew. He didn't want to talk on the telephone, but had said they could meet somewhere on occasion.

Deep Throat didn't want to use the phone even to set up the meetings. He suggested that Woodward open the drapes in his apartment as a signal. Deep Throat could check each day; if the drapes were open, the two would meet that night. But Woodward liked to let the sun in at times, and suggested another signal.

Several years earlier, Woodward had found a red cloth flag lying in the street. Barely one foot square, it was attached to a stick, the type of warning device used on the back of a truck carrying a projecting load. Woodward had taken the flag back to his apartment and one of his friends had stuck it into an old flower pot on the balcony. It had stayed there.

When Woodward had an urgent inquiry to make, he would move the flower pot with the red flag to the rear of the balcony. During the day, Deep Throat would check to see if the pot had been moved. If it had, he and Woodward would meet at about 2:00 am. in a pre-designated underground parking garage. Woodward would leave his sixth-floor apartment and walk down the back stairs into an alley.

Walking and taking two or more taxis to the garage, he could be reasonably sure that no one had followed him. In the garage, the two could talk for an hour or more without being seen. If taxis were hard to find, as they often were late at night, it might take Woodward almost two hours to get there on foot. On two occasions, a meeting had been set and the man had not shown up - a depressing and frightening experience, as Woodward had waited for more than an hour, alone In an underground garage in the middle of the night Once he had thought he was being followed - two well-dressed men had stayed behind him for five or six blocks, but he had ducked into an alley and had not seen them again.

If Deep Throat wanted a meeting-which was rare-there was a different procedure. Each morning, Woodward would check page 20 of his New York Times, delivered to his apartment house before 7:00 am. If a meeting was requested, the page number would be circled and the hands of a clock indicating the time of the rendezvous would appear in a lower corner of the page. Woodward did not know how Deep Throat got to his paper.

The man's position in the Executive Branch was extremely sensitive. He had never told Woodward anything that was incorrect. It was he who had advised Woodward on June 19 that Howard Hunt was definitely involved in Watergate. During the summer, he had told Woodward that the FBI badly wanted to know where the Post was getting its information. He thought Bernstein and Woodward might be followed, and cautioned them to take care when using their telephones. The White House, he had said at the last meeting, regarded the stakes in Watergate as much higher than anyone outside perceived.

(4) Ben Bradlee, The Good Life: Newspapering and Other Adventures (1995)

When I asked for details about Deep Throat's feeling that our lives were in danger, Woodward and Bernstein insisted that we move outdoors. Fear began to seep in as we talked more on my lawn. I thought I knew all about hardball, but I had never yet felt that we were dealing with hitmen. I suspected our telephones were probably being tapped, that our taxes were surely getting a worldclass audit, but I had never felt physically threatened. Now they were saying that our lives were in fact in danger.

(5) The Deceptions of All the President's Men, Probe Magazine V3 N2 (1995)

In his book Deep Truth, author Adrian Havill presents several events in All the President's Men that are, to put it generously, highly suspect. One example is the scene in which Woodward and Bernstein have made their first egregious mistake. They sourced Hugh Sloan's grand jury testimony for a story that Sloan had never told the Grand Jury, showing that Haldeman was one of the inner group at CREEP controlling the mysterious slush fund. In the book, the dejected Woodward and Bernstein walk home in the rain, beaten both physically and symbolically by the elements, with only newspapers over their head to keep them dry. Havill did some checking. It never rained that day. That might seem an inconsequential detail to some, but others will understand that it was a device created to bring drama. How many other "events" were merely fictional devices? Havill found several. For instance, at one point, Carl Bernstein is about to be subpoenaed by CREEP, and Ben Bradlee advised Carl to go hang out at a movie until after 5:00 p.m., then to call into the office. According to the book, Carl went to see Deep Throat, hence the reason for the name "Deep Throat" having been given to Woodward's secret source. But there was no Deep Throat playing anywhere in D.C. at that time. In fact, the theaters were being very cautious, having recently been raided by law enforcement authorities. Not one theater in town was showing Deep Throat....

One of the most astonishingly bald-faced inventions was the process by which Woodward and "Deep Throat" allegedly made contact when they needed to speak to one another. In the book, much is made of the spooky, clandestine meetings between "Deep Throat" and Woodward. When Woodward needed to ask "Deep Throat" something, he was to put a flower pot with a red flag in it on his sixth floor balcony, which, we are supposed to believe, this high level source checked daily. When "Deep Throat" wanted to speak to Woodward, a clock would supposedly be drawn in his copy of the New York Times designating the meeting time. But neither of these scenarios fits the reality of where Woodward lived. Woodward, who could remember the exact room number (710) where he met Martha Mitchell just once, evidently had trouble remembering the address at which he had lived. In an interview he once said it was "606 or 608 or 612, something like that." However, Havill found that Woodward's actual address was 617. This is important, because the balcony attached to 617 faced an interior courtyard. Havill poked around and found that the only way to view a flower pot on the balcony was to walk into the center of the complex, with eighty units viewing you, crane your neck and look up to the sixth floor. Even then, a pot would have been barely visible. There was an alley that ran behind the building that allowed a glimpse of the apartment and balcony, but at an equally difficult angle. And in both cases, we are to believe that this source, who strove hard to protect his identify, would walk up in plain view of the eighty apartments facing the inner courtyard or the alley on a daily basis, on the chance that there might be a sign from Woodward. When Havill tried to poke around, just to look at the place, residents of the building stopped him and inquired who he was and what he was looking for. Unless "Deep Throat" was well known to the residents of the building, his daily visits seem to preclude being able to keep his identity a secret.

As for the clock-in-the-paper, the New York Times papers were delivered not to each door, but left stacked and unmarked in a common reception area. There was no way "Deep Throat" could have known which paper Woodward would end up with each morning.

Havill, in fact, believes that "Deep Throat" is no more real than the movie episode or the rain, but rather, a dramatic device. It certainly worked well. And Woodward's and Bernstein's editor at Simon and Schuster, Alice Mayhew, urged them to "build up the Deep Throat character and make him interesting." While it is now clearly known that at least one of Woodward's informants was, in fact, Robert Bennett, the suggestions from Colodny and Gettlin in Silent Coup about Al Haig and Deborah Davis's suggestions in Katherine the Great about Richard Ober may not be contradictory. Other names that have been suggested have included Walter Sheridan (Jim Hougan in Spooks) and Bobby Ray Inman (also in Spooks). If Havill is correct and there is no "person" who was known as "Deep Throat", it is possible that any or all of the above were passing along information, explicitly not to be sourced or credited to them in any way, on deep background.

(6) Katharine Graham, Personal History (1997)

Yet, despite the care I knew everyone was taking, I was still worried. No matter how careful we were, there was always the nagging possibility that we were wrong, being set up, being misled. Ben would repeatedly reassure me possibly to a greater extent than he may have actually felt by saying that some of our sources were Republicans, Sloan especially, and that having the story almost exclusively gave us the luxury of not having to rush into print, so that we could be obsessive about checking everything. There were many times when we delayed publishing something until the "tests" had been met. There were times when something just didn't seem to hold up and, accordingly, was not published, and there were a number of instances where we withheld something not sufficiently confirmable that turned out later to be true.

At the time, I took comfort in our "two-sources" policy. Ben further assured me that Woodward had a secret source he would go to when he wasn't sure about something a source that had never misled us. That was the first I heard of Deep Throat, even before he was so named by Howard Simons, after the pornographic movie that was popular in certain circles at the time. It's why I remain convinced that there was such a person and that he and it had to be a he was neither made up nor an amalgam or a composite of a number of people, as has often been hypothesized. The identity of Deep Throat is the only secret I'm aware of that Ben has kept, and, of course, Bob and Carl have, too. I never asked to be let in on the secret, except once, facetiously, and I still don't know who he is.

(7) Ben Bradlee, The Good Life: Newspapering and Other Adventures (1995)

The boys (Bob Woodward and Carl Beinstein) had one unbeatable asset: they worked spectacularly hard. They would ask fifty people the same question, or they would ask one person the same question fifty times, if they had reason to believe some information was being withheld. Especially after they got us in trouble by misinterpreting Sloan's answer about whether Haldeman controlled a White House slush fund.

And, of course, Woodward had "Deep Throat," whose identity has been hands-down the best-kept secret in the history of Washington journalism.

Throughout the years, some of the city's smartest journalists and politicians have put their minds to identifying Deep Throat, without success. General Al Haig was a popular choice for a long time, and especially when he was running for president in the 1988 race, he would beg me to state publicly that he was not Deep Throat. He would steam and sputter when I told him that would be hard for me to do for him, and not for anyone else. Woodward finally said publicly that Haig was not Deep Throat.

Some otherwise smart people decided Deep Throat was a composite, if he (or she) existed at all. I have always thought it should be possible to identify Deep Throat simply by entering all the information about him in All the President's Men into a computer, and then entering as much as possible about all the various suspects. For instance, who was not in Washington on the days that Woodward reported putting the red-flagged flower pot on his window sill, signaling Deep Throat for a meeting.

The quality of Deep Throat's information was such that I had accepted Woodward's desire to identify him to me only by job, experience, access, and expertise. That amazes me now, given the high stakes. I don't see how I settled for that, and I would not settle for that now. But the information and the guidance he was giving Woodward were never wrong, never. And it was only after Nixon's resignation, and after Woodward and Bernstein's second book, The Final Days, that I felt the need for Deep Throat's name. I got it one spring day during lunch break on a bench in MacPherson Square. I have never told a soul, not even Katharine Graham, or Don Graham, who succeeded his mother as publisher in 1979. They have never asked me. I have never commented, in any way, on any name suggested to me. The fact that his identity has remained secret all these years is mystifying, and truly extraordinary. Some Doubting Thomases have pointed out that I only knew who Woodward told me Deep Throat was. To be sure. But that was good enough for me then. And now.

(8) Carl Bernstein, CIA and the Media, Rolling Stone Magazine (20th October, 1977)

In 1953, Joseph Alsop, then one of America’s leading syndicated columnists, went to the Philippines to cover an election. He did not go because he was asked to do so by his syndicate. He did not go because he was asked to do so by the newspapers that printed his column. He went at the request of the CIA.

Alsop is one of more than 400 American journalists who in the past twenty-five years have secretly carried out assignments for the Central Intelligence Agency, according to documents on file at CIA headquarters.

Some of these journalists’ relationships with the Agency were tacit; some were explicit. There was cooperation, accommodation and overlap. Journalists provided a full range of clandestine services - from simple intelligence gathering to serving as go-betweens with spies in Communist countries. Reporters shared their notebooks with the CIA. Editors shared their staffs. Some of the journalists were Pulitzer Prize winners, distinguished reporters who considered themselves ambassadors-without-portfolio for their country. Most were less exalted: foreign correspondents who found that their association with the Agency helped their work; stringers and freelancers who were as interested it the derring-do of the spy business as in filing articles, and, the smallest category, full-time CIA employees masquerading as journalists abroad. In many instances, CIA documents show, journalists were engaged to perform tasks for the CIA with the consent of the managements America’s leading news organizations.

The history of the CIA’s involvement with the American press continues to be shrouded by an official policy of obfuscation and deception...

Among the executives who lent their cooperation to the Agency were William Paley of the Columbia Broadcasting System, Henry Luce of Time Inc., Arthur Hays Sulzberger of the New York Times, Barry Bingham Sr. of the Louisville Courier-Journal and James Copley of the Copley News Service. Other organizations which cooperated with the CIA include the American Broadcasting Company, the National Broadcasting Company, the Associated Press, United Press International, Reuters, Hearst Newspapers, Scripps-Howard, Newsweek magazine, the Mutual Broadcasting System, The Miami Herald, and the old Saturday Evening Post and New York Herald-Tribune. By far the most valuable of these associations, according to CIA officials, have been with The New York Times, CBS, and Time Inc.

From the Agency’s perspective, there is nothing untoward in such relationships, and any ethical questions are a matter for the journalistic profession to resolve, not the intelligence community...

Many journalists were used by the CIA to assist in this process and they had the reputation of being among the best in the business. The peculiar nature of the job of the foreign correspondent is ideal for such work; he is accorded unusual access, by his host country, permitted to travel in areas often off-limits to other Americans, spends much of his time cultivating sources in governments, academic institutions, the military establishment and the scientific communities. He has the opportunity to form long-term personal relationships with sources and -- perhaps more than any other category of American operative - is in a position to make correct judgments about the susceptibility and availability of foreign nationals for recruitment as spies.

The Agency’s dealings with the press began during the earliest stages of the Cold War. Allen Dulles, who became director of the CIA in 1953, sought to establish a recruiting-and-cover capability within America’s most prestigious journalistic institutions. By operating under the guise of accredited news correspondents, Dulles believed, CIA operatives abroad would be accorded a degree of access and freedom of movement unobtainable under almost any other type of cover.

American publishers, like so many other corporate and institutional leaders at the time, were willing us commit the resources of their companies to the struggle against “global Communism.” Accordingly, the traditional line separating the American press corps and government was often indistinguishable: rarely was a news agency used to provide cover for CIA operatives abroad without the knowledge and consent of either its principal owner; publisher or senior editor. Thus, contrary to the notion that the CIA era and news executives allowed themselves and their organizations to become handmaidens to the intelligence services. “Let’s not pick on some poor reporters, for God’s sake,” William Colby exclaimed at one point to the Church committee’s investigators. “Let’s go to the managements. They were witting” In all, about twenty-five news organizations (including those listed at the beginning of this article) provided cover for the Agency...

Many journalists who covered World War II were close to people in the Office of Strategic Services, the wartime predecessor of the CIA; more important, they were all on the same side. When the war ended and many OSS officials went into the CIA, it was only natural that these relationships would continue.

Meanwhile, the first postwar generation of journalists entered the profession; they shared the same political and professional values as their mentors. “You had a gang of people who worked together during World War II and never got over it,” said one Agency official. “They were genuinely motivated and highly susceptible to intrigue and being on the inside. Then in the Fifties and Sixties there was a national consensus about a national threat. The Vietnam War tore everything to pieces - shredded the consensus and threw it in the air.” Another Agency official observed: “Many journalists didn’t give a second thought to associating with the Agency. But there was a point when the ethical issues which most people had submerged finally surfaced. Today, a lot of these guys vehemently deny that they had any relationship with the Agency.”

The CIA even ran a formal training program in the 1950s to teach its agents to be journalists. Intelligence officers were “taught to make noises like reporters,” explained a high CIA official, and were then placed in major news organizations with help from management. “These were the guys who went through the ranks and were told, “You’re going to be a journalist,” the CIA official said. Relatively few of the 400-some relationships described in Agency files followed that pattern, however; most involved persons who were already bona fide journalists when they began undertaking tasks for the Agency. The Agency’s relationships with journalists, as described in CIA files, include the following general categories:

* Legitimate, accredited staff members of news organizations - usually reporters. Some were paid; some worked for the Agency on a purely voluntary basis.

* Stringers and freelancers. Most were payrolled by the Agency under standard contractual terms.

* Employees of so-called CIA “proprietaries.” During the past twenty-five years, the Agency has secretly bankrolled numerous foreign press services, periodicals and newspapers - both English and foreign language - which provided excellent cover for CIA operatives.

* Columnists and commentators. There are perhaps a dozen well-known columnists and broadcast commentators whose relationships with the CIA go far beyond those normally maintained between reporters and their sources. They are referred to at the Agency as “known assets” and can be counted on to perform a variety of undercover tasks; they are considered receptive to the Agency’s point of view on various subjects.

Murky details of CIA relationships with individuals and news organizations began trickling out in 1973 when it was first disclosed that the CIA had, on occasion, employed journalists. Those reports, combined with new information, serve as casebook studies of the Agency’s use of journalists for intelligence purposes.

The New York Times - The Agency’s relationship with the Times was by far its most valuable among newspapers, according to CIA officials. [It was] general Times policy to provide assistance to the CIA whenever possible...

CIA officials cite two reasons why the Agency’s working relationship with the Times was closer and more extensive than with any other paper: the fact that the Times maintained the largest foreign news operation in American daily journalism; and the close personal ties between the men who ran both institutions...

The Columbia Broadcasting System - CBS was unquestionably the CIA’s most valuable broadcasting asset. CBS president William Paley and Allen Dulles enjoyed an easy working and social relationship. Over the years, the network provided cover for CIA employees, including at least one well-known foreign correspondent and several stringers; it supplied outtakes of newsfilm to the CIA; established a formal channel of communication between the Washington bureau chief and the Agency; gave the Agency access to the CBS newsfilm library; and allowed reports by CBS correspondents to the Washington and New York newsrooms to be routinely monitored by the CIA. Once a year during the 1950s and early 1960s, CBS correspondents joined the CIA hierarchy for private dinners and briefings...

At the headquarters of CBS News in New York, Paley’s cooperation with the CIA is taken for granted by many news executives and reporters, despite the denials. Paley, 76, was not interviewed by Salant’s investigators. “It wouldn’t do any good,” said one CBS executive. “It is the single subject about which his memory has failed.”

At Newsweek, Agency sources reported, the CIA engaged the services of several foreign correspondents and stringers under arrangements approved by senior editors at the magazine...

“To the best of my knowledge:’ said [Harry] Kern, [Newsweek’s foreign editor from 1945 to 1956] “nobody at Newsweek worked for the CIA.... The informal relationship was there. Why have anybody sign anything? What we knew we told them [the CIA] and the State Department.... When I went to Washington, I would talk to Foster or Allen Dulles about what was going on .... We thought it was admirable at the time. We were all on the same side.” CIA officials say that Kern's dealings with the Agency were extensive...

When Newsweek was purchased by the Washington Post Company, publisher Philip L. Graham was informed by Agency officials that the CIA occasionally used the magazine for cover purposes, according to CIA sources. “It was widely known that Phil Graham was somebody you could get help from,” said a former deputy director of the Agency... But Graham, who committed suicide in 1963, apparently knew little of the specifics of any cover arrangements with Newsweek, CIA sources said...

Information about Agency dealings with the Washington Post newspaper is extremely sketchy. According to CIA officials, some Post stringers have been CIA employees, but these officials say they do not know if anyone in the Post management was aware of the arrangements...

Other major news organizations - according to Agency officials, CIA files document additional cover arrangements with the following news gathering organizations, among others: the New York Herald Tribune, Saturday Evening Post, Scripps-Howard Newspapers, Hearst Newspapers, Associated Press, United Press International, the Mutual Broadcasting System, Reuters and The Miami Herald...

“And that's just a small part of the list,” in the words of one official who served in the CIA hierarchy. Like many sources, this official said that the only way to end the uncertainties about aid furnished the Agency by journalists is to disclose the contents of the CIA files - a course opposed by almost all of the thirty-five present and former CIA officials interviewed over the course of a year.

The CIA’s use of journalists continued virtually unabated until 1973 when, in response to public disclosure that the Agency had secretly employed American reporters, William Colby began scaling down the program. In his public statements, Colby conveyed the impression that the use of journalists had been minimal and of limited importance to the Agency.

He then initiated a series of moves intended to convince the press, Congress and the public that the CIA had gotten out of the news business. But according to Agency officials, Colby had in fact thrown a protective net around his most valuable intelligence assets in the journalistic community...

At the headquarters of CBS News in New York, Paley’s cooperation with the CIA is taken for granted by many news executives and reporters, despite the denials. Paley, 76, was not interviewed by Salant’s investigators. “It wouldn’t do any good,” said one CBS executive. “It is the single subject about which his memory has failed.”

Time and Newsweek magazines. According to CIA and Senate sources, Agency files contain written agreements with former foreign correspondents and stringers for both the weekly news magazines. The same sources refused to say whether the CIA has ended all its associations with individuals who work for the two publications. Allen Dulles often interceded with his good friend, the late Henry Luce, founder of Time and Life magazines, who readily allowed certain members of his staff to work for the Agency and agreed to provide jobs and credentials for other CIA operatives who lacked journalistic experience.

At Newsweek, Agency sources reported, the CIA engaged the services of several foreign correspondents and stringers under arrangements approved by senior editors at the magazine...

After Colby left the Agency on January 28th, 1976, and was succeeded by George Bush, the CIA announced a new policy: “Effective immediately, the CIA will not enter into any paid or contract relationship with any full-time or part-time news correspondent accredited by any US news service, newspaper, periodical, radio or television network or station.” ... The text of the announcement noted that the CIA would continue to “welcome” the voluntary, unpaid cooperation of journalists. Thus, many relationships were permitted to remain intact.

(9) Deborah Davis, interviewed by Kenn Thomas of Steamshovel Press (1992)

Bob Woodward has consistently lied about his background ever since the first time anybody started asking who this person is. He came from Wheaton, Illinois. His father was a judge. He joined the Navy and became a communications officer, which is not Naval Intelligence per se. Naval intelligence is a separate organization. Communications officers are at the very highest level of receiving coded and top secret information from around the world and they get it before anybody else does. It's up to them to relay this information to the people in power.

In Woodward's case, first he was in the Navy serving somewhere in California for four years. At the end of his term he was in California, before that he was on a ship I believe. He's never said what he was doing in California. He just won't talk about it. But you remember that this was the time of the height of the anti-war movement and there was a domestic counter-intelligence operation going on called Operation Chaos, which was coordinating Army, Navy and FBI and CIA intelligence on the anti-war movement, spying on leaders and so on, trying to find foreign influence. And I believe that this is what Woodward was involved in at that time.

So after his four years were up he was eligible to leave the Navy, having completed his service. Instead he re-enlisted for another year and he came to Washington and he started working in a top secret Naval unit inside the Pentagon. Actually, they went between the Pentagon and the White House. This was during the first years of Nixon's presidency. And I believe that at this time he started working directly with Richard Ober, who was the deputy chief of counter-intelligence under James Angleton. He was the one who was running Operation Chaos and I believe that he was the one who was Deep Throat. I disagree with those people in Silent Coup, although it hardly matters who exactly it was because I know Woodward had many sources.

But the point is that at this time he was getting top secret information. He was briefing the Joint Chiefs of Staff, he was briefing the National Security Council and he was briefing Alexander Haig, who was Nixon's chief of staff. He was right in the very, very center of the Nixon White House in terms of the information that was being conveyed and the people he knew. After that, he decided for some mysterious reason that he wanted to be a reporter and he went to the Post and the Post has thousands of applications a year of experienced reporters, most of whom never get in. But instead they took this guy who couldn't write, who had never been a reporter in his life and they said, "You have to learn how to write better so go work on the suburban paper for a year and then we'll hire you." Now I don't know how they decided that he was somebody they wanted to cultivate or whether somebody had the word on him ahead of time or what. But after a year he came to the Post and right away Ben Bradlee, the executive editor, started giving him the choice assignments. They felt a common bond between each other because Bradlee had a very similar back ground in the Navy himself.

Carl Bernstein was coming from a whole different place. He was a very messed up person, you know, had a lot of trouble keeping his job at the Post. He would always fall asleep on the job, stay up all night and miss deadlines and he was just a mess. If it weren't for the newspaper guild rules about not firing reporters, he would have been fired a long time ago. But he had a sense about politics. He still does. He had a very good sense about politics and he hated Nixon because during the McCarthy era, when Nixon was a congressman, his family, his father and mother, who were very left-wing, had experienced a lot of persecution during the McCarthy era. So he associated Nixon with this. And he had his won reasons for wanting to do a story that he thought might lead to exposing Nixon and bringing down Nixon.

It's a very strange friendship. There was a lot of tension between Woodward and Bernstein and there's a very strong bond between them because each of them owes the other one the fact that they are now millionaires and can get book contracts for any amount of money they want.

(10) David Guyatt, Subverting the Media (undated)

In an October 1977, article published by Rolling Stone magazine, Bernstein reported that more than 400 American journalists worked for the CIA. Bernstein went on to reveal that this cozy arrangement had covered the preceding 25 years. Sources told Bernstein that the New York Times, America’s most respected newspaper at the time, was one of the CIA’s closest media collaborators. Seeking to spread the blame, the New York Times published an article in December 1977, revealing that “more than eight hundred news and public information organisations and individuals,” had participated in the CIA’s covert subversion of the media.

“One journalist is worth twenty agents,” a high-level source told Bernstein. Spies were trained as journalists and then later infiltrated – often with the publishers consent - into the most prestigious media outlets in America, including the New York Times and Time Magazine. Likewise, numerous reputable journalists underwent training in various aspects of “spook-craft” by the CIA. This included techniques as varied as secret writing, surveillance and other spy crafts.

The subversion operation was orchestrated by Frank Wisner, an old CIA hand who’s clandestine activities dated back to WW11. Wisner’s media manipulation programme became known as the “Wisner Wurlitzer,” and proved an effective technique for sending journalists overseas to spy for the CIA. Of the fifty plus overseas news proprietary’s owned by the CIA were The Rome Daily American, The Manilla Times and the Bangkok Post.

Yet, according to some experts, there was another profound reason for the CIA’s close relations with the media. In his book, “Virtual Government,” author Alex Constantine goes to some lengths to explore the birth and spread of Operation Mockingbird. This, Constantine explains, was a CIA project designed to influence the major media for domestic propaganda purposes. One of the most important “assets” used by the CIA’s Frank Wisner was Philip Graham, publisher of the Washington Post. A decade later both Wisner and Graham committed suicide – leading some to question the exact nature of their deaths. More recently doubts have been cast on Wisner’s suicide verdict by some observers who believed him to have been a Soviet agent.

(11) Carl Bernstein, History lesson: GOP must stop Bush, USA Today (23rd May, 2004)

Thirty years ago, a Republican president, facing impeachment by the House of Representatives and conviction by the Senate, was forced to resign because of unprecedented crimes he and his aides committed against the Constitution and people of the United States. Ultimately, Richard Nixon left office voluntarily because courageous leaders of the Republican Party put principle above party and acted with heroism in defense of the Constitution and rule of law.

"What did the president know and when did he know it?" a Republican senator - Howard Baker of Tennessee - famously asked of Nixon 30 springtimes ago.

Today, confronted by the graphic horrors of Abu Ghraib prison, by ginned-up intelligence to justify war, by 652 American deaths since presidential operatives declared "Mission Accomplished," Republican leaders have yet to suggest that George W. Bush be held responsible for the disaster in Iraq and that perhaps he, not just Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, is ill-suited for his job.

Having read the report of Major Gen. Antonio Taguba, I expect Baker's question will resound again in another congressional investigation. The equally relevant question is whether Republicans will, Pavlov-like, continue to defend their president with ideological and partisan reflex, or remember the example of principled predecessors who pursued truth at another dark moment.

Today, the issue may not be high crimes and misdemeanors, but rather Bush's failure, or inability, to lead competently and honestly.

"You are courageously leading our nation in the war against terror," Bush told Rumsfeld in a Wizard-of-Oz moment May 10, as Vice President Cheney, Secretary of State Colin Powell and senior generals looked on. "You are a strong secretary of Defense, and our nation owes you a debt of gratitude." The scene recalled another Oz moment: Nixon praising his enablers, Bob Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, as "two of the finest public servants I've ever known."

Like Nixon, this president decided the Constitution could be bent on his watch. Terrorism justified it, and Rumsfeld's Pentagon promoted policies making inevitable what happened at Abu Ghraib - and Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. The legal justification for ignoring the Geneva Conventions regarding humane treatment of prisoners was enunciated in a memo to Bush, dated Jan. 25, 2002, from the White House counsel.

"As you have said, the war against terrorism is a new kind of war," Alberto Gonzales wrote Bush. "In my judgment, this new paradigm renders obsolete Geneva's strict limitations on questioning of enemy prisoners and renders quaint some of its provisions." Quaint.

Since January, Bush and Rumsfeld have been aware of credible complaints of systematic torture. In March, Taguba's report reached Rumsfeld. Yet neither Bush nor his Defense secretary expressed concern publicly or leveled with Congress until photographic evidence of an American Gulag, possessed for months by the administration, was broadcast to the world.

Rumsfeld then explained, "You read it, as I say, it's one thing. You see these photographs and it's just unbelievable. ... It wasn't three-dimensional. It wasn't video. It wasn't color. It was quite a different thing." But the report also described atrocities never photographed or taped that were, often, even worse than the pictures - just as Nixon's actions were frequently far worse than his tapes recorded.

It was Barry Goldwater, the revered conservative, who convinced Nixon that he must resign or face certain conviction by the Senate - and perhaps jail. Goldwater delivered his message in person, at the White House, accompanied by Republican congressional leaders.

Republicans on the House Judiciary Committee likewise put principle above party to cast votes for articles of impeachment. On the eve of his mission, Goldwater told his wife that it might cost him his Senate seat on Election Day. Instead, the courage of Republicans willing to dissociate their party from Nixon helped Ronald Reagan win the presidency six years later, unencumbered by Watergate.

Another precedent is apt: In 1968, a few Democratic senators - J. William Fulbright, Eugene McCarthy, George McGovern and Robert F. Kennedy - challenged their party's torpor and insisted that President Lyndon Johnson be held accountable for his disastrous and disingenuous conduct of the Vietnam War, adding weight to public pressure, which, eventually, forced Johnson not to seek reelection

Today, the United States is confronted by another ill-considered war, conceived in ideological zeal and pursued with contempt for truth, disregard of history and an arrogant assertion of American power that has stunned and alienated much of the world, including traditional allies. At a juncture in history when the United States needed a president to intelligently and forcefully lead a real international campaign against terrorism and its causes, Bush decided instead to unilaterally declare war on a totalitarian state that never represented a terrorist threat; to claim exemption from international law regarding the treatment of prisoners; to suspend constitutional guarantees even to non-combatants at home and abroad; and to ignore sound military advice from the only member of his Cabinet - Powell - with the most requisite experience. Instead of using America's moral authority to lead a great global cause, Bush squandered it.