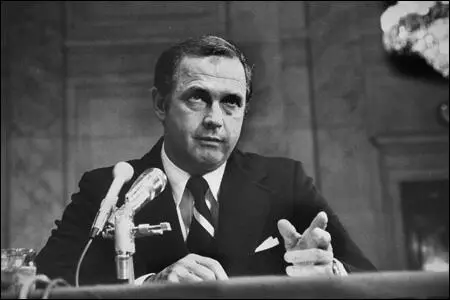

Alexander P. Butterfield

Alexander Porter Butterfield, the son of a United States Navy pilot, was born at Pensacola, Florida, on 6th April, 1926. Butterfield studied at the University of California but during the Second World War he left to join the United States Air Force and flew the Lockheed P-38 Lightning in the Pacific War.

Butterfield remained in the USAF and took part in the Korean War and the Vietnam War, where he won the Distinguished Flying Cross. He also served in Australia as a senior Defense Department representative. Later he was project officer for the General Dynamics F-111.

In 1968 Richard Nixon was elected as president of the United States. Nixon's chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, had studied with Butterfield at the University of California. Butterfield later claimed that Haldeman contacted him and suggested that he became Deputy Assistant to the President. However, Haldeman claimed that it was Butterfield who asked him for a job. Butterfield retired from the USAF and took up the post. Butterfield supervised internal security. This meant he had to work closely with the Secret Service. Butterfield also helped to organize the installation of the secret taping system in the White House.

In December, 1972, Nixon appointed Butterfield as administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration. However, Butterfield was drawn into the Watergate Scandal after Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein had interviewed Hugh Sloan. During the interview Sloan admitted that Butterfield had been in charge of "internal security". Woodward passed this information to a member of the Senate Committee headed by Sam Ervin.

On 25th June, 1973, John Dean testified that at a meeting with Richard Nixon on 15th April, the president had remarked that he had probably been foolish to have discussed his attempts to get clemency for E. Howard Hunt with Charles Colson. Dean concluded from this that Nixon's office might be bugged. On Friday, 13th July, Butterfield appeared before the committee and was asked about if he knew whether Nixon was recording meetings he was having in the White House. Butterfield reluctantly admitted details of the tape system which monitored Nixon's conversations. Butterfield also said that he knew "it was probably the one thing that the President would not want revealed". This information did indeed interest Archibald Cox and Sam Ervin demand that Richard Nixon hand over the White House tapes. Nixon refused and so Cox appealed to the Supreme Court.

On 20th October, 1973, Nixon ordered his Attorney-General, Elliot Richardson, to fire Archibald Cox. Richardson refused and resigned in protest. Nixon then ordered the deputy Attorney-General, William Ruckelshaus, to fire Cox. Ruckelshaus also refused and he was sacked. Eventually, Robert Heron Bork, the Solicitor-General, fired Cox.

Richard Nixon was unable to resist the pressure and on 23rd October he agreed to comply with the subpoena and began releasing some of the tapes. The following month a gap of over 18 minutes was discovered on the tape of the conversation between Richard Nixon and H. R. Haldeman on June 20, 1972. Nixon's secretary, Rose Mary Woods, denied deliberately erasing the tape.

On 27th July, 1974, the House Judiciary Committee adopts the first Article of Impeachment by a vote of 27-11. The Article charged Nixon with the obstruction of the investigation of the Watergate break-in. Two weeks later three senior Republican congressmen, Barry Goldwater, Hugh Scott, John Rhodes visited Nixon to tell him that they are going to vote for his impeachment. Nixon, convinced that he will lose the vote, decides to resign as president of the United States.

Butterfield remained as administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration under Gerald Ford. He resigned on 31st March, 1975, and became a business executive. In July, Fletcher Prouty told Daniel Schorr that Butterfield had been the CIA's spy in the White House. Butterfield denied this claim and threatened to sue the two men for libel. Time Magazine reported: "Despite his impressive record, Schorr gets into trouble because he is often too eager and cuts corners. He has been known to behave like an anxious rookie out to impress by elbowing others aside and pushing hard. Just before the Watergate cover-up indictments, for example, he went on-camera to predict that the grand jury would name more than 40 people. Seven names came down. At CBS, Washington Correspondent Leslie Stahl cordially detests him because, she tells friends, he hogged her Watergate stories."

In 1995 Butterfield told The Hartford Courant that he was convinced that Deep Throat was Mark Felt. On the 25th anniversary of Nixon's resignation in 1999, Felt told a reporter that it would be "terrible" if someone in his position had been Deep Throat. "This would completely undermine the reputation that you might have as a loyal employee of the FBI," he said. "It just wouldn't fit at all."

Felt retired to Santa Rosa, California. In 2001 Mark Felt had a stroke that robbed him of his memory. Before this happened Felt had told his daughter Joan that he was Deep Throat. In May, 2005, Felt's lawyer, John O'Connor, went public with the news. Felt was quoted as saying: "I don’t think being Deep Throat was anything to be proud of. You should not leak information to anyone." However, he added: "If you know your government is engaging in illegal and/or immoral acts, then you have an obligation to speak out that overrides confidentiality agreements and secrecy laws. It's never wrong to inform on serious criminal acts no matter who is perpetrating them." Shortly afterwards Bob Woodward confirmed that Felt had provided him with important information during the Watergate investigation. Ben Bradlee also said that Felt was Deep Throat. However, Carl Bernstein was quick to add that Felt was only one of several important sources.

Primary Sources

(1) H. R. Haldeman, The Ends of Power (1978)

There was definitely a desire on Nixon's part to have the tapes for his own use in whatever historical work he might do after leaving office, and for reference while he was in office. But the main driving force that led Nixon to approve the use of a taping system was his desire for an accurate record of everything that was said in meetings with foreign guests, government officials and his own staff. He recognised the problem of either intentional or unintentional distortion or misunderstanding and became more and more concerned about the absence of such a record...

In a meeting-between Nixon and me, he decided to install a taping system. It was done in utmost secrecy. Among the President's top advisers, only I knew of its existence. And I soon learned why he insisted on such absolute secrecy. Nixon never intended anyone to hear the tapes except himself. They were never, even to be transcribed.

I remember the day clearly when his attitude towards the tapes was made evident to me. Early in 1972, before Watergate, Alex Butterfield, the White House assistant who maintained custody of the tapes, entered my office. "We're piling up a horrendous amount of tape," he said. "Obviously, nobody is going to sit and listen to all of it. It would take years. So I assume you're going to want it typed up."

He asked me if he should get a crew started transcribing the tapes. "Otherwise, it's going to just build up to an insurmountable task." I raised the question with the President that day. "Do you want to start making transcripts of the tapes?"

He startled me by saying vehemently, "Absolutely not." He didn't want transcripts made at any time. Nobody was, going to listen to those tapes, ever, except himself. Then he added, "I'll never even have Rose Woods listen to them. Rose doesn't know I'm making the tapes. I say things in this office that I don't want even Rose to hear."

At that point Nixon looked up at me sharply as if becoming aware, of what he was saying. "Uh . . . possibly you can hear them, too, but no one else."

Thus the tapes were kept secret even from Rose Mary Woods, until Watergate. And then Rose and I were the first persons to whom Nixon turned regarding the tapes. He asked me to listen and take notes on the March 21, 1973 'troublesome' conference with John Dean - and I ended up with a perjury charge. Rose did little better - ridiculed in the press as she desperately reached for a foot pedal while stretching back for a telephone to demonstrate how 18 minutes of the June 20 tape had been 'accidentally' erased.

Rose would never have had to go through that ordeal if the tapes had not survived as evidence. In the whole story of the White House recording system the one question asked over and over again by both friends and foes of Nixon is "Why didn't he destroy the tapes?" In a telephone call long after I left the White House, and during the period when Nixon was going through the agony of listening to many of the White House tapes prior to releasing the transcripts or turning the tapes over to the prosecutors, Nixon laughed wistfully and said, "You know, it's funny, I was,just listening to one of the early April tapes of a meeting between you and me. I had completely forgotten this, but in that meeting I said to you, 'Bob, maybe we should get rid of all those tapes and just save the national security stuff.' And you said no, you thought we should keep them. Oh, well."

(2) Time Magazine (28th July, 1975)

The day after a story broke in the press alleging that the CIA had planted a spy in the White House, Colonel Fletcher Prouty telephoned CBS Newsman Daniel Schorr with the startling news that former Nixon Aide Alexander Butterfield was the man. Schorr rushed the retired Air Force officer onto the network's Morning News for his disclosure, which generated sensational headlines. But last week, when Butterfield denied Prouty's charges and hinted he might sue him for libel, the colonel, in an interview with his hometown paper in Springfield, Mass., expressed second thoughts. Then Prouty confused matters further with a switch back to his original story. This jack-in-the-box behavior roused questions not only about Prouty's reliability but Schorr's as well.

By week's end, grizzled Veteran Schorr, 58, thought his exposé was looking "awful." But he insists he had reason to trust Prouty because the colonel had earlier given him a rock-hard exclusive on his role in a plot to assassinate Fidel Castro. Still, Schorr concedes that he never took the time to check the Butterfield allegation with the two Air Force officers who Prouty claims gave him the information, or try very hard to reach Butterfield himself. Nevertheless, Schorr says, "I still think my only alternative was to go. We're in a strange business here in TV news. You can't check on the validity of everything... I can't be in a position of suppressing Prouty. What if he's right? I can't play God."

The controversy is not the first to embroil Schorr in recent years. Early in the Nixon Administration he angered the President by reporting, accurately, that there was no evidence to support Nixon's claim that he had programs ready to aid parochial schools. His reward: Nixon ordered the FBI to investigate him. During Watergate, Schorr became TV's most visible investigative reporter and shared three Emmys with his colleagues. Last February Schorr moved into new territory by reporting President Ford's fear that the clamor to investigate the CIA might reveal the agency's role in foreign assassination plots. Two months later, former CIA Director Richard Helms denounced Schorr's reporting as "lies" and called him "Killer Schorr, Killer Schorr." Recent disclosures by the Senate Intelligence Operations Committee have largely vindicated Schorr.

Despite his impressive record, Schorr gets into trouble because he is often too eager and cuts corners. He has been known to behave like an anxious rookie out to impress by elbowing others aside and pushing hard. Just before the Watergate cover-up indictments, for example, he went on-camera to predict that the grand jury would name more than 40 people. Seven names came down. At CBS, Washington Correspondent Leslie Stahl cordially detests him because, she tells friends, he hogged her Watergate stories.

(3) Jim Hougan, Secret Agenda: Watergate, Deep Throat and the CIA (1984)

That the CIA should have infiltrated the White House is a startling idea, but McMahon is by no means its only adherent. As H. R. Haldeman has written: "Were there CIA 'plants' in the White House? On July 10, 1975, Chairman Lucien Nedzi of the House of Representatives Intelligence Committee released an Inspector-General's Report in which the CIA admitted there was a 'practice of detailing CIA employees to the White House and various government agencies. The IG Report revealed there were CIA agents in 'intimate components of the Office of the President.' Domestic CIA plants are bad enough, but in 'intimate components' of the Office of the President?"' Haldeman then goes on to speculate about the identities of the CIA men in the White House. His main suspect is Alexander Butterfield, the former Air Force officer whose White House responsibilities included overall supervision of the presidential taping system. That system consisted of some two dozen room microphones and telephone taps that Wong's Secret Service detachment had installed in the White House and at Camp David; voice-activated by the Presidential Locator System or manually by Butterfield, the microphones and taps fed into a set of concealed Sony tape recorders.' Haldeman's suspicions about Butterfield - who denies that he was a CIA asset-were shared by Rose Mary Woods, President Nixon's personal secretary. Together they criticize Butterfield for voluntarily revealing the existence of the taping system; they point with suspicion to Butterfield's early service as a military aide to GOP nemesis Joseph Califano, and make much of the fact that the circumstances of Butterfield's White House appointment are disputed.

The disputed circumstances concerning Butterfield's appointment are these: both Butterfield and Haldeman insist that it was the other who made the first approach with respect to working at the White House. Butterfield says that Haldeman, a college chum, telephoned him to ask if he would serve as his deputy. Haldeman contradicts this, saying that his call to Butterfield was in response to a letter that Butterfield had written to him, asking for a White House appointment.

Butterfield does not recall having written such a letter. A second element in the dispute is Butterfield's insistence that he had to resign from the Air Force in order to take the job at the White House. Haldeman says that this resignation, which terminated a promising military career, was entirely unnecessary. The suspicion is that the resignation was part of a protocol concerning cover arrangements between the CIA and the Air Force.

Haldeman and Woods are not alone in their suspicions of Butterfield, or in their concern over the Inspector General's report. If Bill McMahon is correct, McCord's seconding of CIA personnel in undercover assignments at the White House amounted to the calculated infiltration of a uniquely sensitive Secret Service unit: the staff responsible for maintaining and servicing the presidential taping system, and for storing its product. Moreover, unless both Haldeman and McMahon are mistaken - about Butterfield's secret allegiance and McCord's loan of personnel to Wong - then the CIA would seem to have had unrivaled access to the President's private conversations and thoughts. Charles Colson, among others, believes that this is precisely what occurred. "The CIA had tapes of everything relating to the White House," Colson told me. "And they destroyed them two days after (Senator Mike) Mansfield asked them to save all of their tapes."

(4) Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, All the President's Men (1974)

Since June 17, 1972, the reporters had saved their notes and memos, reviewing them periodically to make lists of unexplored leads. Many items on the lists were the names of CRP and White House people who the reporters thought might have useful information. By May 17, 1973, when the Senate hearings opened, Bernstein and Woodward had gotten lazy. Their nighttime visits were scarcer, and, increasingly, they had begun to rely on a relatively easy access to the Senate committee's staff investigators and attorneys. There was, however, one unchecked entry on both lists - presidential aide Alexander P. Butterfield. Both Deep Throat and Hugh Sloan had mentioned him, and Sloan had said, almost in passing, that he was in charge of "internal security." In January, Woodward had gone by Butterfield's house in a Virginia suburb. No one had come to the door.

In May, Woodward asked a committee staff member if Butterfield had been interviewed.

"No, we're too busy."

Some weeks later, he had asked another staffer if the committee knew why Butterfield's duties in Haldeman's office were defined as "internal security"

The staff member said the committee didn't know, and maybe it would be a good idea to interview Butterfield. He would ask Sam Dash, the committee's chief counsel. Dash put the matter off. The staff member told Woodward he would push Dash again. Dash finally okayed an interview with Butterfield for Friday, July 13, 1973.

On Saturday the 14th, Woodward received a phone call at home from a senior member of the committee's investigative staff. "Congratulations," he said. "We Interviewed Butterfield. He told the whole story."

What whole story?

"Nixon bugged himself."

He told Woodward that only junior staff members had been present at the interview, and that someone had read an excerpt from John Dean's testimony about his April 15 meeting with the President.

"The most interesting thing that happened during the conversation was very near the end," Dean had said. "He (Nixon) got up out of his chair, went behind his chair to the corner of the Executive Office Building office and in a barely audible tone said to me he was probably foolish to have discussed Hunt's clemency with Colson." Dean had thought to himself that the room might be bugged.

Butterfield was a reluctant witness. He said that he knew it was probably the one thing that the President would not want revealed. The interrogators pressed-and out floated a story which would disturb the presidential universe as none other would.

The existence of a tape system which monitored the President's conversations had been known only to the President himself, Haldeman, Larry Higby, Alexander Haig, Butterfield and the several Secret Service agents who maintained it. For the moment, the information was strictly off the record.

The reporters were again concerned about a White House set-up. A taping system could be disclosed, they reasoned, and then the President could serve up doctored or manufactured tapes to exculpate himself and his men. Or, having known the tapes were rolling, the President might have induced Dean - or anyone else - to say incriminating things and then feign ignorance himself. They decided not to pursue the story for the moment.

All Saturday night, the subject gnawed at Woodward. Butterfield had said that even Kissinger and Ehrlichman were unaware of the taping system. The Senate committee and the special prosecutor would certainly try to obtain the tapes, maybe even subpoena them.

(5) Richard Nixon, Memoirs (1978)

Early Monday morning Haig called to tell me that Haldeman's former aide Alex Butterfield had revealed the existence of the White House taping system to the Ervin Committee staff and that it would become public knowledge later that day.

I was shocked by this news. As impossible as it must seem now, I had believed that the existence of the White House taping system would never be revealed. I thought that at least executive privilege would have been raised by any staff member before verifying its existence.

The impact of the revelation of our taping system was stunning. The headline in the New York Daily News was Nixon 'Bugged Own Offices'.

Fred Buzhardt sent a letter to Ervin confirming that the system described by Butterfield did exist and pointing out that it was similar to the one that had been employed by the previous administration. Buzhardt's letter provoked swift reactions laced with righteous indignation. LBJ Aides Disavow System was the Washington Post's headline. Johnson's former domestic aide, Joseph Califano, said, "I think this is an outrageous smear on a dead President." Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., said that it was "inconceivable" that John Kennedy would have approved such a taping system. Kennedy's former aide, Dave Powers, then curator of the Kennedy Library, denied that there were tapes. But Army Signal Corps technicians who had installed the Johnson taping system gave Fred Buzhardt sworn affidavits about the placement of the machines and microphones, and within a few days the archivist at the Johnson Library in Austin confirmed the existence of the LBJ tapes. Then, the next day, the Kennedy Library admitted that in fact there were 125 tapes and 68 Dictabelt recordings of different meetings and phone conversations.

(6) Len Colodny and Robert Gettlin, Silent Coup: The Removal of Richard Nixon (1991)

At that very moment, President Nixon was in Bethesda Naval Hospital in suburban Maryland, suffering from viral pneumonia. He had awakened in the early hours of the previous morning with a high fever and complaining of severe chest pains. That day he spent in bed. He had one tense conversation with Sam Ervin in regard to the committee's request for all White House papers that might relate to the Senate's investigation. Nixon had refused to turn over the papers, citing executive privilege. When his condition worsened and a chest X ray showed that he had viral pneumonia, the decision was made to move him to the hospital....

Nixon may well have believed that he was on top of the day's events, but during that weekend the president remained completely unaware that his political fate was being seriously undermined by the prospective testimony before the Watergate committee of Alexander Butterfield.

That Nixon remained ignorant of Butterfield's doings during the weekend of July 14 and 15 has been regarded by Watergate historians and journalists as little more than an oddity to be briefly noted. It was much more than that.

After showing Butterfield to the door, Democratic staffers Armstrong and Boyce rushed to find Sam Dash at his office, while Republican counsel Sanders went on a similar mission to locate Fred Thompson. When Armstrong and Boyce came into his office, Sam Dash later wrote in his book Chief Counsel, "they both looked wild-eyed. Scott was sweating and in a state of great excitement. As soon as he had closed the door the words tumbled out of his mouth as he told me about Butterfield's astounding revelation.... We became overwhelmed with the explosive meaning of the existence of such tapes. We now knew there had been a secret, irrefutable 'witness' in the Oval Office each time Dean met with Nixon, and if we could get the tapes we could now do what we had thought would be impossible-establish the truth or falsity of Dean's accusations against the President."

Thompson was at the bar at the Carroll Arms hotel, having a drink with a reporter, when Sanders dragged him outside to a small park, checked to see if they could be overheard, and blurted out the news.

There were two problems with any proposed Butterfield testimony. The first was that he did not want to testify and had suggested that the committee get Higby or Haldeman to testify in public about the taping system. Second, he was scheduled to leave on Tuesday, July 17, for the Soviet Union to help negotiate a new aviation treaty.

Learning this, Dash found Sam Ervin and they agreed that Butterfield should be compelled to testify on Monday, and Ervin authorized Dash to prepare a subpoena for Butterfield.

For his part, Fred Thompson and Assistant Minority Counsel Howard Liebengood met with Howard Baker on Saturday morning. As Thompson later wrote, "Baker thought it inconceivable that Nixon would have taped his conversations if they contained anything incriminating. I agree d.... The more I thought about what had occurred, the more I considered the possibility that Butterfield had been sent to us as part of a strategy: the president was orchestrating the whole affair and had intended that the tapes be discovered." For that reason, the Republicans came to the same conclusion already reached by Dash and Ervin, that Butterfield should give his testimony in public as soon as possible.

Thompson may well have been correct that Butterfield had been sent to the committee as part of a strategy-but if he was, it was not the president's strategy.

That Saturday morning, as Baker met with his aides, Butterfield flew to New Hampshire to dedicate a new air traffic control facility in Nashua County, and he told us he was so unconcerned about his possible testimony to the Senate that he didn't even prepare for an appearance before the Senate.

"I didn't have the slightest clue" that the committee would call him to testify on Monday, he told us. "No, no-why would I ever do that? I didn't give it one goddamn thought. (Meeting with the Senate staffers) was just another session to me. I know for a fact that I never did anticipate being called by the committee. So I never would have written out any statements, or answers or comments or anything like that having to do with me testifying."