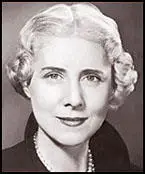

Clare Boothe Luce

Ann (Clare) Boothe, the second of two children, was born in New York City on 10th April, 1903. Her father, William Franklin Boothe, a violinist, had a succession of jobs in orchestras, and had been married before. Her mother, Anna Clara Schneider, was a singer and dancer. She was disowned by her parents when she got married. As Roman Catholics, they considered their daughter as "living in sin".

According to Stephen Shadegg: "When Anna was eighteen, she left home to work in New York, first as a salesgirl in a department store, later singing and dancing with the chorus in a New York theater... She was strikingly beautiful, with long chesnut-colored hair. Her admirers described her eyes as violet. She had a fair singing voice and a good figure. No doubt she was ambitious for a career, but like most girls her age, when the choice came, she preferred love and marriage."

Clare had few childhood playmates other than her brother David. Clare's father, who was often unemployed, taught his daughter to read at an early age. She later recalled reading books more suitable to adults than to children. She claimed that she started reading Edward Gibbon's The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire before she was nine years old.

In 1911 William Franklin Boothe took his family on the road. He had a new job as a concert violinist with a traveling symphony orchestra. The tour ended in Nashville, Tennessee, when the promoters went broke. A wealthy patron helped him establish a soft-drink bottling business in the city. The venture was a success and Clare was able to attend the primary classes in the fashionable Ward Belmont School. Anna was furious when her husband sold the bottling factory and moved the family to Chicago where he found work playing his violin in an orchestra.

Boothe left the family to go off with another woman when Clare was only nine years old. Mrs. Boothe told her children that their father was dead. Clare remembers not being able to understand why her mother exhibited more anger than grief. Mrs. Boothe took her children home to Hoboken, New Jersey, where her father, William Snyder, ran a livery business. He died soon afterwards and the family decided to New York City.

Anna Boothe now decided that her pretty daughter should become a child-actress. Her first job was as understudy to Mary Pickford in The Good Little Devil . Mary did not miss a performance and so Clare never got the opportunity to appear on stage. This was followed by being the understudy to the child star in the Ernest Truex comedy, The Dummy . This time Clare got the chance to do a half-dozen performances but it convinced her that she did not want to be an actress.

In 1915 Mrs. Boothe obtained a job as a saleswoman for costume jewelry and was able to enroll Clare at the Cathedral School of St. Mary in Garden City, Long Island. Soon afterwards, she became very close to Elizabeth Cobb, the daughter of Irvin Shrewsbury Cobb, a successful journalist who worked for The Saturday Evening Post. Clare was invited to spend her first boarding-school holiday with the Cobbs. This was the first of many visits to a home where she met George Horace Lorimer, Richard Harding Davis, Fanny Brice, George H. Doran and Frank Nelson Doubleday.

Clare's friend, Dorothy Burns, later claimed that she was a very good student: "When the other girls were reading a racy, contraband account of their favorite movie star, Clare would have a volume of Racine or Molière. She wasn't stuffy about it. She just didn't have time for trash. She even read while she brushed her hair or when she bathed, propping a book on the faucet of the tub. She took longer baths than any girl I have ever known before or since."

In December 1917, the Boothe family moved to Old Sound Beach, Connecticut. During the First World War Clare worked as a volunteer for the Sound Beach Red Cross. She now attended Castle School at Tarrytown. By this time she was very interested in a future career in journalism and became editor of the school newspaper, The Drawbridge .

Anna Boothe married Dr. Albert E. Austin in 1920. He was a member of the Connecticut House of Representatives. He was also health officer for Greenwich, chief of staff at the local hospital, president of the Greenwich Bank and Trust Company and Grand Master of the Greenwich Masonic Lodge. Austin, a forty-two-year-old bachelor, was four years older than his new wife.

After leaving school Clare became secretary to Ava Belmont, a leading figure in the Women's National Party. She also became involved in the struggle for women's suffrage and also worked closely with Alice Paul and Inez Mulholland and took part in several demonstrations. The author of Clare Boothe Luce (1970) has argued: "Clare's assignment was to attract public attention, enlist new converts, and help destroy the notion that feminine activists had to be rich, chesty old matrons or disgruntled, plain spinsters - in short, to radiate youth and sex appeal."

In 1922 Clare met George Tuttle Brokaw, a forty-three-year-old millionaire playboy bachelor. He was older than her father but they married on 10th August, 1923. Over 2,500 people were invited to the wedding that The New York Journal-American described it as "the most important social event of the season". The following year Clare gave birth to a daughter Ann.

Brokaw decided he needed a new family home and paid $250,000 for a six acre estate at Sands Point on Long Island. However, Clare was not happy, as her friend, Stephen Shadegg, has pointed out: "After a honeymoon period of sobriety, George returned to his old ways and was drinking heavily... When he was sober he was very pleasant and a good companion. But as time went on he was rarely sober. And under the influence of alcohol he ventured his jealousies, sometimes inflicting physical as well as verbal abuse on Clare. In the last four years of their marriage she suffered four early miscarriages."

Clare told her mother that she was considering leaving her husband. She argued that she should stay with him, pointing out that no man could line long who drank so heavily and that if he died, Clare would be left a very rich widow with her whole life ahead of her. Clare rejected the idea and on 20th May 1929 the marriage was dissolved. Brokaw, who was worth $12 million, gave her a settlement of a $425,000 trust fund. This assured her of an after-taxes income of more than $25,000 a year. George Tuttle Brokaw remarried soon after the divorce. His second wife was the 23-year-old, Frances Ford Seymour. Clare's mother was correct, and Brokaw died six years later in Hartford Sanatorium, where he had been committed as an alcoholic, leaving $5 million to his young wife. She later married Henry Fonda and was the mother of Jane Fonda and Peter Fonda, but committed suicide by cutting her throat with a razor on her 42nd birthday while in the Craig House Sanitarium for the Insane.

Soon after her divorce Clare joined the staff of the fashion magazine Vogue where she wrote captions for photographs. At a party she met Donald Freeman, the managing editor of Vanity Fair. He was described at the time as "short, overweight, and with an alarmingly receding hair-line". They began to go out together. Clare later recalled: "He encouraged me at a critical time in my life to believe in myself, and my talents. I loved him for that, but not in the same way he loved me."

Freedman arranged for Clare to meet Frank Crowninshield, the editor of the magazine. At the interview he asked her to come back in a week's time with 100 suggestions suitable for publication in Vanity Fair. On the result of this exercise he gave her a job on the magazine. Clare asked if that meant her ideas were good ones. Crowninshield replied: "No, my child. Some of them are perfectly dreadful. but two at least are excellent. And one good idea a week is about all a magazine should expect from a novice assistant editor."

One of Clare's first assignments was to write captions for its popular feature, We Nominate for the Hall of Fame . This included articles on people like Thomas Mann, Ernest Hemingway, Walter Gropius, Louis Bromfield and Pablo Picasso. In August, 1930, she introduced a new feature, We Nominate for Oblivion . Her targets included politicians such as Reed Smott ("because his chief qualifications for holding the position of Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee is that he is an apostle in the Mormon Church of Utah and doesn't count on his fingers") and Smith W. Brookhart ("because he has made political capital out of snitching on those of his hosts who serve alcohol").

Clare also played a part in the downfall of Jimmy Walker. She wrote: "James Joseph Walker, the Mayor of the City of New York, seems to be his political record; the one fact of importance the existence of his irresistible charm. During his six years as Manhattan's Chief Executive, the personal popularity of this small man has grown in direct ratio to the shrinkage of his prestige. In fact his prestige has now shrunk to such a microscopic point and his popularity expanded to such splendid proportions, that he no longer belongs to the realm of politics, but to the realm of legend and literature." Soon afterwards Walker resigned in September 1932. Facing fifteen charges of corruption, Walker fled to Europe and did not return until he was convinced he would not be prosecuted for his financial offences.

Clare became a close friend of both John Franklin Carter and Arthur Krock. They were all interested in politics and Krock claimed that on one occasion Clare suggested that America needed a new political party with the slogan, "A New Deal for America". A few months later Carter suggested the term to Franklin D. Roosevelt who used it in his successful 1932 Presidential Election campaign.

Clare's friends included Herbert Bayard Swope, Hugh S. Johnson, William Paley, and George S. Kaufman. Her name often appeared in gossip columns written by Walter Winchell and the author of Clare Boothe Luce (1970) has pointed out: "In many of these reports there is a not too subtle suggestion that Clare was using her sex and beauty to attract men for the sake of publicity. If she did deliberately seek to be in the company of people of prominence and power, it must be conceded she was amazingly successful."

The young writer, Irwin Shaw, was a friend during this period and later argued that she was only attracted to older men with power: "She played the field but she never played me." Alexander Woollcott, who was a close friend with Dorothy Parker, commented: "Most of us were delighted to discover that a girl who could read without moving her lips didn't have to look like Dorothy Parker." Clare later admitted in later life that "up to the age of forty or so, I was surprised when a man didn't make a pass at me."

It was rumoured that Clare was romantically involved with the sixty-one year old, Bernard Baruch. He later recalled: "When she comes into a room she attracts everybody's attention by the glow that emanates from her. Her extraordinary spirit shines out of her eyes. When courage was given out, she was sitting on the front bench." Clare's friend, Arthur Krock, admitted that Baruch wanted to marry her. However, according to Krock, although she was very fond of him she had no desire to become his wife. Under the influence Baruch, she became a supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. Baruch helped Roosevelt establish the National Recovery Administration (NRA) and Clare became, she said, "the lowly kitchen maid of the New Deal cabinet".

In 1933 Clare became managing editor of Vanity Fair. She attempted to change the look of the magazine by illustrating articles on people with candid photographs. She also used photographs that would tell the news with a minimum amount of accompanying text. However, senior members of the staff resisted this new approach and in February 1934 she resigned from the magazine.

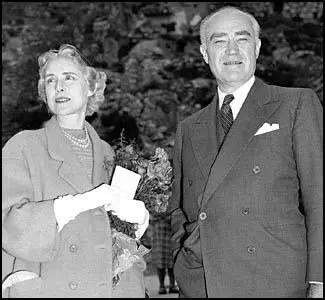

Clare met Henry Luce, the owner of Time Magazine and the business magazine Fortune at a party in 1934, was a wealthy man with a fortune estimated at $10 million. After talking for a couple of hours he told her: "I want to tell you that you are the great love of my life. And someday I am going to marry you." Luce was married to Lila Ross Hotz and she dismissed his suggestion and went on a long holiday to Europe. Luce did not accept this rejection and met up with her in Paris. As Stephen Shadegg has pointed out: "The courtship which followed was not a particularly romantic one. Harry Luce found it difficult to express his love in the conventional words of lovers. Like Clare, he always seemed on his guard, fearful lest someone might discover the soft, eager, not-at-all-cocksure human being behind his gruff exterior. But his devotion and determination were unmistakable. Intellectually he was the most interesting man Clare had ever encountered. She fell in love with him."

Wilfrid Sheed, the author of Clare Boothe Luce (1982) has argued: "The possibility that there was a powerful mutual attraction hedged with normal lunges and hesitations seemed ruled out by their importance and ambition. Yet Harry was in fact precisely her type: physically, he was close enough to other men whom I know she finds interesting (although Harry photographed grimly) to suggest that their romance wasn't just power calling to power... Nevertheless, it was important for her to make clear for the record that he pursued her, because the non-record, or myth, ran all the other way. To begin with, Harry was already married and had two sons, not to mention two edifying magazines. The Other Woman was always public enemy number one in those days, whatever the circumstances; but in this case, the circumstances were bad too. Harry looked like a pillar of rectitude (an old Presbyterian trick-his sexual rectitude was to prove just about the national average) and he also looked absentminded, as if a smart woman could steal him while he wasn't looking."

Luce divorced his wife, Lila Ross Hotz, in September, 1935. According to Robert E. Herzstein, the author of Henry R.Luce: A Political Portrait of the Man Who Created the American Century (1994): "Lila was devastated when Luce confronted her with his intention to divorce her. But they maintained a closeness and were in constant contact, often discussing their children's education and careers, among other things.''

On 23rd November, 1935, Henry married Clare. The followed year he began publishing the picture magazine, Life. Over the next few years Clare began writing plays. Abide with Me (1935) was a story of a young woman married to a rich old alcoholic. The play received very bad reviews. The New York Herald Tribune reported: "Her first step in the theater is stumbling. The unhappy predication of her heroine married to a sadistic drunkard is authentic enough for any drama, but she has not let these protagonists reveal themselves in significant action. Having sat and chatted for most of two acts, they are suddenly galvanized into frenetic and rather ridiculous action. Where a neophyte might be pardoned for a good many slips in dramatic structure, it is not so easy to forgive sheer bad writing."

In 1936 Laird Goldsborough, the foreign editor of Time Magazine, attempted to persuade Luce to take sides in the conflict in Spain. George Teeple Eggleston, who worked for the company at the time, has claimed that it was Goldsborough who persuaded Luce to support General Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War. According to Eggleston: "Time's conservative foreign news editor, Laird Goldsborough, promptly slanted all news stories in his department in favor of General Franco's rebel insurgents."

This approach was criticised by Archibald MacLeish, who worked on Fortune, another magazine owned by Luce, who "promptly bombarded Luce memos denouncing Franco's coalition of landowners, the Church, and the army". Goldsborough responded by arguing: "On the side of Franco are men of property, men of God, and men of the sword. What positions do you suppose these sorts of men occupy in the minds of 700,000 readers of Time? ... They resent communists, anarchists, and political gangsters - those so-called Spanish Republicans."

George Teeple Eggleston points out that Clare did not agree with her husband on this issue and supported the Republicans during the war: "Clare was violently anti-Franco and promptly contributed a thousand dollars to the pro-Communist Abraham Lincoln Brigade, which was gathering volunteers in New York City to fight against Franco in Spain."

Clare was also a close friend of Harry Bridges, a former member of the Industrial Workers of the World. Clare later admitted that he nearly converted her to Marxism: "I suspect now that the appeal of Communism for many young people and for me lay in its religious aspect. Communism was a complete, authoritarian religious structure, and the liberal mind had grown weary and confused defending the inalienable right to disorganize and exploit society according to its own notions of liberty. This had led to Hooverism and rugged individualism."

Clare Boothe Luce's play, The Women , opened in New York City on 26th December, 1936. It has been suggested that George S. Kaufman actually wrote the play but he always denied it. Justin Brooks Atkinson, wrote in the New York Times: "Miss Boothe's alleycats scratched and spit with considerable virtuosity... but The Women is mainly a multi-scented portrait of the modern New York wife on the loose spraying poison over the immediate landscape... Miss Boothe has compiled a workable play out of the withering malice of New York's most unregenerate worldlings. This reviewer did not like it." The play ran for two years and in 1937 Reliance Pictures paid $125,000 for the film rights and it was later turned into a movie starring Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford and Rosalind Russell.

Her next play, Kiss the Boys Goodbye, ran for two hundred and eighty-six performances. She later claimed that the play was a political allegory about Fascism in America: "We are not, perhaps, sufficiently aware that Southernism is a particular and highly matured form of Fascism with which America has lived more or less peacefully for seventy-five years." It was later turned into a movie starring Don Ameche, Mary Martin and Oscar Levant.

According to her friend, Wilfrid Sheed, Clare "had not lived together connubially" after Henry Luce resumed having affairs in the late 1930s. "Harry's famous conscience made it impossible for him to conduct two affairs at once, so as soon as someone, anyone, else came along, that was that. Whoever came along, I deduce, did so after about five years. If so, it suggests that their professional partnership got stronger as the chemistry got weaker."

Clare Boothe Luce was deeply concerned about the emergence of Adolf Hitler and the growth of fascism in Europe. Her anti-Nazi play, Margin for Error, opened at the Plymouth Theater in New York City on 3rd November, 1939. Henry Luce commented: "In all these years of failure the difficulty has not in fact been to get national socialism on stage. The real difficulty has been to get on stage a convincing rebuttal to national socialism." It was later turned into a movie directed by Otto Preminger.

In February 1940, Clare went on a tour of Europe. This included her meeting old friends in London, Winston Churchill, Lord Beaverbrook and the American Ambassador, Joseph P. Kennedy, who told her: "Remember this, we Americans can live quite comfortably in a world of English snobbery and British complacency... but we can't live in a world of Nazis and German brutality." Clare was in Brussels when the German Army invaded the country in May, 1940.

On her arrival back in the United States she began work on Europe in the Spring (1940). In the book she attacked isolationism: "We were a people who had left the Old World in order to redefine and live a Christian way of life, and who found that one of the principles of a Christian way of life was liberty and justice for all. So we fought for it, and that is what made us Americans. And out of that revolutionary belief, by the grace of God, we made of ourselves a great and mighty nation... But I think if we no longer believe what we believed then and are no longer willing to fight for it, it is very likely that our Christian Democracy is finished." Wilfrid Sheed has argued that it is a "strong, evocative book... it is easily her best claim as a global thinker".

In July, 1940, Clare, Henry Luce, C. D. Jackson, Freda Kirchwey, Raymond Gram Swing, Robert Sherwood, John Gunther, Leonard Lyons, Ernest Angell and Carl Joachim Friedrich established the Council for Democracy. According to Kai Bird the organization "became an effective and highly visible counterweight to the isolation rhetoric" to America First Committee led by Charles Lindbergh and Robert E. Wood: "With financial support from Douglas and Luce, Jackson, a consummate propagandist, soon had a media operation going which was placing anti-Hitler editorials and articles in eleven hundred newspapers a week around the country."

The isolationist Chicago Tribune accused the Council for Democracy of being under the control of foreigners: "The sponsors of the so-called Council for Democracy... are attempting to force this country into a military adventure on the side of England." George Seldes also attacked the organization arguing that it was being mainly financed by Henry Luce. However, according to The Secret History of British Intelligence in the Americas, 1940-45, a secret report written by leading operatives of the British Security Coordination (Roald Dahl, H. Montgomery Hyde, Giles Playfair, Gilbert Highet and Tom Hill), William Stephenson and BSC played an important role in the Council for Democracy: "William Stephenson decided to take action on his own initiative. He instructed the recently created SOE Division to declare a covert war against the mass of American groups which were organized throughout the country to spread isolationism and anti-British feeling. In the BSC office plans were drawn up and agents were instructed to put them into effect. It was agreed to seek out all existing pro-British interventionist organizations, to subsidize them where necessary and to assist them in every way possible. It was counter-propaganda in the strictest sense of the word. After many rapid conferences the agents went out into the field and began their work. Soon they were taking part in the activities of a great number of interventionist organizations, and were giving to many of them which had begun to flag and to lose interest in their purpose, new vitality and a new lease of life. The following is a list of some of the larger ones... The League of Human Rights, Freedom and Democracy... The American Labor Committee to Aid British Labor... The Ring of Freedom, an association led by the publicist Dorothy Thompson, the Council for Democracy; the American Defenders of Freedom, and other such societies were formed and supported to hold anti-isolationist meetings which branded all isolationists as Nazi-lovers."

Clare Boothe Luce was opposed to Roosevelt attempt to win a third-term and supported Wendell Willkie in the the 1940 Presidential Election. This caused a dispute with her fellow anti-isolationist journalist, Dorothy Thompson. In her column in early October, Thompson announced she was deserting Willkie to vote for Franklin D. Roosevelt, who she said was essential to the future of America and the world. She dismissed the anti-third termers as being the victims of sentimental tradition. In a speech on 15th October, 1940, Clare described Thompson as "a woman with a great heart and a fine brain, who had fallen victim to an anxiety neurosis because she had not been able to arouse the nation to physically do battle with Hitler... Miss Thompson became the victim of the emotional disease called acute fear." Boothe Luce gave over forty speeches in favour of Willkie during the campaign. As Stephen Shadegg has pointed out: "It was obvious to her that America would have to enter the war and she regarded Roosevelt's promise to the mothers and fathers of America that he would never send their boys to fight in a foreign war as the ultimate in self-serving political dishonesty."

During the early days of the Second World War she reported for Life on events in Italy, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, England and China. This included interviews with General Harold R.L.G. Alexander, Richard Stafford Cripps, Chiang Kai-Shek, and General Joseph Stilwell. She also came under attack and later wrote: "Until you have heard the death scream in a shell or bomb through the insensible air, impersonally seeking you out personally, you never quite believe that you are mortal."

A member of the Republican Party Clare Luce was a candidate for Connecticut to Congress in 1942. She was attacked by Gregory Mason, a former figure in the America First Committee in the New York Times: "Mrs. Luce suffers from two enormous political disadvantages, her connections with Willkie, and her husband, Henry R. Luce. She belongs to the narrow-minded, bitter and fast-dwindling Willkie faction which is determined to blacklist every American who did not agree with the Roosevelt foreign policy before Pearl Harbor. She is bound to be influenced by her husband, whose yellow journals are doing all they can to keep alive the disunity and acrimony which marred American discussion of foreign affairs before Japan's wanton attack on us." Luce won the election by a margin of less than seven thousand votes.

In her maiden speech she launched a savage attack on Vice President Henry A. Wallace. She spoke rarely in Congress, and when she did, they usually dealt with American foreign policy and were generally interpreted to be anti-Roosevelt. The New Republic commented that she "blew hot and cold from liberalism to isolationism". Clare claimed that Sam Rayburn gave her advice on how to be a successful politician, "explain nothing, deny everything, demand proof - don't listen to it - and give the opposition hell".

Senator William Fulbright described Clare Boothe Luce of making full use of her feminine charms: "More mentally vigorous than a great many Congresswomen. She was a very beautiful and attractive woman and she used this feminine advantage in every argument or discussion we ever had." Walter Winchell quoted one Senator as saying, "Don't you think it's beneath the dignity of this House to have one of its members voted among the six women in America with the most beautiful legs." Clifton Fadiman commented: "After a careful study of her speeches, I am convinced that no woman of our time has gone further with less mental equipment."

During this period Clare Luce developed extreme right wing views and became well known for her outspoken opposition to communism and her support for free enterprise. When her old friend, Wendell Willkie, argued in his book One World (1943), where he called for a post-war world which was a union of free nations, she wrote a letter advising him "to stop drinking, lose forty pounds and adopt a more realistic understanding of the Communists' announced plan to conquer the world." Dorothy Parker disliked her opposition to Willkie's idea for a United Nations, commented: "Her retirement from public office is the concern of everybody who has the welfare of the nation and a desire for enduring peace close at their hearts."

On 11th January, 1944, Clare's daughter Ann, a nineteen-year-old student at Stanford University, was killed in a car accident. Devastated by the loss of her only child that she suffered a nervous breakdown. After discussions with Bishop Fulton Sheen, Clare converted to Roman Catholicism. Sheen commented "I have never met or talked with a more brilliant mind than Clare. She is scintillating. Her mind is like a rapier." Clare retired from Congress and returned to writing.

Her husband, Henry Luce, shared her right-wing views. According to David Halberstam: "Luce's politics hardened in the postwar years and Time had become increasingly Republican in its tone. He had been stunned by Truman's defeat of Dewey in 1948. Then in the fall of 1949 China had fallen, the Democratic administration had failed to save Chiang, and that was too much; Truman, and even more Acheson, would have to pay the price. Time was now committed and politicized, an almost totally partisan instrument. The smell of blood was in the air. There was a hunger now in Luce to put a Republican back in power. It was as if Luce, between elections, stood as the leader of the opposition, a kingmaker who had failed to produce a king. The fall of China and the rise of a post-war anti-Communist mood had produced the essential issue to use against the Democrats: softness on Communism."

Clare Boothe Luce supported Arthur Vandenberg to become the Republican Party candidate in the 1948 Presidential Election. She was extremely disappointed that he had dropped out of the race. He later told her: "I knew I had lung cancer. I couldn't seek the nomination knowing I wouldn't survive in office." Vandenberg died in April 1951.

The novelist, Wilfrid Sheed, met her during this period. "Her face was as clear as Harry's was clouded, with a radiance that was not simply sexy... the right word was simply cheerful, like lights going on in a dark house. It was almost as if she had chosen Luce as a foil, to emphasize her own good qualities, which included manifest ease, friendliness, and uptake... She met me at the door... and her cool voice might have been designed for welcoming nervous people. She spoke slower than she had to, in a slightly facetious drawl that picked up stray bits of humor as it went along, and in later years she could slow this down even more, to the brink of woolliness... Clare did have one besetting weakness - a lifelong craving to be thought clever - that is guaranteed to undo one occasionally."

Henry Luce used his media empire to get Dwight D. Eisenhower elected as president. In 1953 Eisenhower appointed her ambassador to Italy; the first American woman ambassador to a major country. She immediately caused controversy when she made a speech about communist influence over the trade unions in Italy. Thirty-five left-wing signed a petition condemning her attempt to interfere illegally in the internal affairs of Italy and demanded that she should leave the country. Pressure was taken off Boothe Luce when the body of Wilma Montesi was found on a beach on 9th April 1953 and rumours began to circulate that Piero Piccioni, the son of government minister, Attilio Piccioni, was involved in her death.

Claudio Accogli, a Italian historian, argues that Luce was heavily involved in covert anti-communist activities with local CIA personnel. Larry Hancock adds: "With no-holds barred political activism and heavy spending (including the support of the SIFAR/Italian Army Secret Service), Luce and the CIA managed to block the probable takeover of the center-left governments, an alliance between Christian Democrats (DC) and the Socialist Democratic Party (PSI)."

In 1956 Clare Boothe Luce was taken ill and had to return to the United States. When she was examined it was discovered that she was suffering from arsenic poisoning. The CIA came to the conclusion that someone on the embassy staff was trying to kill her. Gerry Miller, the CIA agent on the staff was asked to investigate. After spending some time spying on the staff who cooked her food they discovered that the arsenic had come from the paint on the ceiling of her bedroom that was being dislodged by people walking on the floor above.

In 1959 Eisenhower appointed Luce ambassador to Brazil. The opposition to her appointment in Congress was led by Wayne Morse of Oregon. Morse raised the issue of her "willful interference in Italian politics". Clare commented Morse's actions were the result of him being "kicked in the head by a horse." This remark proved so controversial that Clare resigned the ambassadorship a few days later.

Boothe Luce favoured Lyndon Johnson for the Democratic Party nomination in the 1960 Presidential Election. At a meeting Johnson assured Clare that he would "never, never, never accept the Vice-Presidency". A week after Johnson had taken the second spot to John F. Kennedy she asked him why he changed his mind, he replied: "At least I'm only one heart beat away from the job I really want." Clare did not campaign against the Democrats because of her close relationship with Joseph Kennedy.

Clare Boothe Luce and Henry Luce were strong opponents of Fidel Castro and his revolutionary government in Cuba. They joined with Hal Hendrix, Paul Bethel, William Pawley, Virginia Prewett, Dickey Chapelle, Edgar Ansel Mowrer, Edward Teller, Arleigh Burke, Leo Cherne, Ernest Cuneo, Sidney Hook, Hans Morgenthau and Frank Tannenbaum to form the Citizens Committee to Free Cuba (CCFC). On 25th March, 1963, the CCFC issued a statement: "The Committee is nonpartisan. It believes that Cuba is an issue that transcends party differences, and that its solution requires the kind of national unity we have always manifested at moments of great crisis. This belief is reflected in the broad and representative membership of the Committee."

The Luce family also funded Alpha 66. In 1962 Alpha 66 launched several raids on Cuba. This included attacks on port installations and foreign shipping. The authors of Deadly Secrets: The CIA-Mafia War Against Castro and the Assassination of JFK (1981) argues that Clare Boothe Luce paid for one of the boats used in these raids: "The anti-communist blonde took a maternal interest in the three-man crew she adopted... She brought them to New York three times to mother them."

Luce later told Gaeton Fonzi that the attacks had been organized by her friend, William Pawley: "Luce said that Pawley had gotten the idea of putting together a fleet of speedboats-sea-going Flying Tigers as it were-which would be used by the exiles to dart in and out of Cuba on intelligence gathering missions. He asked her to sponsor one of these boats and she agreed." John Newman argues in his book, Oswald and the CIA (1995) that Pawley was working for the CIA in Miami. He argues that he was involved with Haroldson L. Hunt and quotes James P. Hosty as saying: "H. L. Hunt was backing Pawley's people, and they were also getting support from Henry Luce."

William E. Kelly, who has investigated the work of Luce, has argued: "Clare Booth Luce wrote a weekly column and an occasional photo feature for Life. The magazine ran articles on the impending invasion of Cuba before the Bay of Pigs, and in one column, a week before the Cuban Missile Crisis, Clare Booth Luce chastised the President for ignoring the evidence of offensive missiles in Cuba.... She also apparently saw the U2 photos leaked by the Air Force liaison to the National Photographic Interpretation Center, before they were revealed to the president. After the Cuban Missile crisis was successfully resolved, Luce began writing stories about Mongoose, the CIA’s covert operations against Castro, which you could have read all about in Life, as they ran photos and stories about Operation Red Cross (aka the Bayo/Pawley Mission), and other anti-Castro missions."

Luce's media empire was used against John F. Kennedy. When Kennedy was assassinated, Luce's Life Magazine purchased the Zapruder Film. Soon after the assassination they also successfully negotiated with Marina Oswald the exclusive rights to her story. This story never appeared in print. Luce published individual frames of Zapruder's film but did not allow the film to be screened in its entirety.

Clare remained active in right-wing politics and in 1964, campaigned for Barry Goldwater of Arizona, the Republican candidate for president. Later that year Clare and Henry Luce retired to their home in Phoenix. He died there on on 28th February, 1967.

In 1975 Senator Richard Schweiker, a member of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, began investigating the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Two years later the House Select Committee on Assassinations was established. Soon afterwards Schweiker was visited by Vera Glaser, a syndicated Washington columnist. Glaser told him she had just interviewed Luce and that he had given her some information relating to the assassination. According to Gaeton Fonzi, who worked for Schweiker: "Schweiker immediately called Luce and she, quite cooperatively and in detail, confirmed the story she had told Glaser."

In his book, The Last Investigation (1993), Fonzi points out that during the campaign against Fidel Castro in 1963 the captain of one of the boats they were using, was approached by Lee Harvey Oswald who offered his services as a potential Castro assassin. "He said his group didn't believe Oswald, suspected he was really a Communist and decided to keep tabs on him. Fernandez said they found that Oswald was, indeed, a Communist, and they eventually penetrated his cell and tape-recorded his talks, including his bragging that he could shoot anyone". Fernandez also told Luce that Oswald then suddenly came into money and went to Mexico City and then Dallas.

In 1981 President Ronald Reagan appointed Clare to the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board. With that, she moved from Honolulu to an apartment in the Watergate complex in Washington. She served on the board until 1983, the year Reagan awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Clare Boothe Luce died of a brain tumor on 9th October, 1987, and was buried at Mepkin Abbey, in South Carolina. A large sum of money was used to establish the Clare Boothe Luce Program. It has been claimed that the organization has given grants of more than $120 million to support over 1,550 women studying science, mathematics and engineering.

The Clare Boothe Luce Award, established in 1991 by the Heritage Foundation, for distinguished contributions to the conservative movement. Winners have included Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, William F. Buckley, Shelby Cullom Davis, Kathryn Wasserman Davis, Richard B. Cheney, Milton Friedman, James L. Buckley and Richard DeVos.

Primary Sources

(1) Clare Boothe Luce, McCall's Magazine (1947)

In the crash and depression years that followed the boom, some of the men and women found that they had abandoned, in moments of bitter revulsion, their very holds on life itself. Men jumped out of windows because they had lost their last or their first million. Some who had kept their millions, lost their minds. Many took to drink, a few to psychoanalyst couches, obsessed with the notion that somehow (they did not know how or why) they were responsible for the bread-lines that had formed in Times Square.

During the depression years, four of my good friends, two of them beautiful and adored women, and two talented men, committed suicide. Nobody knew the real reason. Perhaps life itself had become an "ism" they were tired of.

This flurry of "death by design" was as hard for me as it was for many to understand. It was like the very first leaves that drop from a tree on a still, autumn day.

(2) Wilfrid Sheed, Clare Boothe Luce (1982)

The point about Brokaw is that he is not an anecdote. He just happened. Her marriage to him is not a cute story, and she doesn't try to make it so, any more than she does with her mother, brother, or any hard reality: although once the brute facts of Brokaw are disposed of, there are about two and a half laughs left over, to cover a six-year marriage. Brokaw indeed proved, between bouts of insipidity, to be an ugly, murderously violent drunk, whose only contribution to human betterment was his trick of hiding gin in his golf trophies. On the road to delirium, he occasionally passed through a valley of despond where he talked about how he should have been a Presbyterian missionary (both Clare's husbands had this curious tendency). He even attempted sometimes to play the stirring phrase "The good, the true and the beautiful" on the banjo, with predictably strange results.

Funny now, but a nightmare then. All Clare's dreams of being a great writer, or anything else, dribbled away bit by bit. Her yearbook yearnings joined the other hot air in that volume. Brokaw didn't go to work, although he did occasionally go to golf, and it was impossible to get down to anything ambitious in his gloomy presence. Because when sober he was sodden with remorse, and when drunk he just tootled along until his faithful manservant came rolling up with the straitjacket. Literally, says Clare. In between, he swatted Clare around enough, possibly, to have produced those miscarriages: the school of hard knocks indeed, long before Clare entered public life.

(3) Stephen Shadegg, Clare Boothe Luce (1970)

It has been suggested elsewhere that Stilwell was sympathetic to the Chinese Communists. Mrs. Luce expresses a contrary opinion. She said Stilwell wanted to win the war and to establish China as a first-rate power. This, he believed, could never be achieved until the provincial rulers had been replaced by a tough, well-trained army under the absolute command of the central government.

Stilwell was no diplomat. Clare reported that in private he referred to Chiang as "the peanut" or "that bastard." The Burma campaign had been an ignominious defeat for Stilwell. He blamed the British and the Chinese and was extremely critical of General Claire Chennault.

It was Clare's opinion that Stilwell's insistence on reopening the Burma front was prompted by a desire to erase the memory of the defeat he had suffered in that area. She supported Chiang's contention that if thirty divisions could be equipped, they would be more effectively employed in other theaters. Clare, who was extremely air-minded, agreed with Chennault and Chiang, who were contending that air transport should be employed to supply China and that Stilwell's demand for the construction of the Ledo Burma Road would result in a wasteful undertaking.

(3) Dr. Gregory Mason, The New York Times (17th August, 1942)

Mrs. Luce suffers from two enormous political disadvantages, her connections with Willkie, and her husband, Henry R. Luce. She belongs to the narrow-minded, bitter and fast-dwindling Willkie faction which is determined to blacklist every American who did not agree with the Roosevelt foreign policy before Pearl Harbor. She is bound to be influenced by her husband, whose yellow journals are doing all they can to keep alive the disunity and acrimony which marred American discussion of foreign affairs before Japan's wanton attack on us.

(4) Jonathan P. Herzog, The Spiritual-Industrial Complex: America's Religious Battle Against Communism in the Early Cold War (2011)

The most visible, and unlikeliest, incarnation of spiritual inoculation was Congresswoman Clare Boothe Luce of Connecticut. A playwright, journalist, and onetime sex symbol for New York's literati, she had increased her influence substantially after marrying publishing mogul Henry R. Luce in 1935. Like many writers and intellectuals in the 1930s, she shunned organized religion and flirted with Communism only to reject Marx as the Red Decade waned. In 1942 a local political strategist convinced Luce to run for a Connecticut congressional seat. She won handily as a Republican and built her reputation on routine and sometimes entertaining assaults on Democratic foreign policy.

Her immunization and subsequent crusade against Communism did not begin with international observations or the forceful warnings of J. Edgar Hoover. It flowed instead from personal tragedy. In January 1944, her daughter, Ann, died in a car accident during her senior year at Stanford University. At the time Luce was in San Francisco visiting Ann, and in her initial grief she spontaneously ran to a nearby Catholic church. Kneeling alone and spiritually broken, she began a two-year journey toward conversion, aided by Fulton Sheen. As he had done with Louis Budenz, Elizabeth Bentley, and other wayward souls, Sheen shepherded Luce away from the pitfalls of secularism and Communism into the welcoming arms of Catholicism. Luce had America's foremost anti-Communist teacher, but Sheen quickly realized the potential of his pupil. "She intuits," he wrote. "She sees things all at once." In February 1946, Luce was confirmed at St. Patrick's Cathedral.

Following her conversion Luce decided not to seek reelection. Instead, she spent much of her final year in Congress advocating a religious solution to Communism. Separating genuine calls for sacralization from those born of political expediency was difficult in the Cold War, but few could doubt Luce's earnestness. Her rhetoric smoldered with zealous intensity. Following a long line of Catholic argument, she called Communism "the ultimate perfected religion of materialism." Widening her critique beyond card-carrying members of the Communist Party, she defined materialists as people who believed the "common man lives by bread alone." The New Deal had exalted the material over the spiritual. It had weakened America, Luce joked, by convincing men and women that "all will be good and happy when all have two cars in every garage, two chickens in every pot, and two pairs of nylons on every chicken." A citizenry of full bellies and empty souls was already halfway down the path to Communist conversion.

She continued the fight after leaving Congress in magazine articles and convention speeches. In a contest with Communism, Truman acknowledged, religion was part of the solution, but for Luce a Christian revival was the sine qua non of any victory. In her worldview faith was a constant - a requisite need for belief in something beyond reason that all humans shared. Against a burning faith, whether false or true, lukewarm opinions had little chance. "The yawning agnostics," she warned, "the sneering finger-drumming atheists, the drooling, sentimental, misty-eyed humanitarians... will not save us from the fiery sons of Marx." Only men and women who burned with an intense faith could withstand the challenge of Communism.

(5) William E. Kelly, Journalists and JFK: Real Dizinfo Agents At Dealey Plaza (May 2011)

With the new Democratic administration, Luce brought aboard a new publisher, C. D. (Charles Douglas) Jackson, an OSS hand and President Eisenhower’s personal administrative assistant on psychological warfare and Cold War strategy.

While Jackson would remain in the background, devising strategy, Clare Booth Luce wrote a weekly column and an occasional photo feature for Life. The magazine ran articles on the impending invasion of Cuba before the Bay of Pigs, and in one column, a week before the Cuban Missile Crisis, Clare Booth Luce chastised the President for ignoring the evidence of offensive missiles in Cuba. She says she had been told this by "her boys," who ran commando missions in and out of Cuba. But she also apparently saw the U2 photos leaked by the Air Force liaison to the National Photographic Interpretation Center, before they were revealed to the president. The NPIC U2 photos of missiles in Cuba were also shown to Sen. Keating (R. NY) by Col. Philip J. Corso, who later bragged about leaking it in his book The Day After Roswell.

After the Cuban Missile crisis was successfully resolved, Luce began writing stories about Mongoose, the CIA’s covert operations against Castro, which you could have read all about in Life, as they ran photos and stories about Operation Red Cross (aka the Bayo/Pawley Mission), and other anti-Castro missions. Clare was particularly proud of “her boys,” the team of anti-Castro commandos who ran maritime missions into Cuba in their speed boat, and she financially backed, though they were also supported by the CIA. They were based out of the CIA’s JMWAVE base in Florida, affiliated with the DRE and led by Julio Fernandez.

On the night of the assassination, Clare Booth Luce says she was awakened from sleep by a phone call by Fernandez. He claimed to have exclusive knowledge of the accused assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, including recordings of him, and other records that appeared to substantiate his pro-Castro leanings i.e. the original Phase One cover-story, Castro did it. Luce told him to call the FBI. But he didn’t, or at least there is no record of him having done so.

(6) Wilfrid Sheed, Clare Boothe Luce (1982)

Clare and Harry got themselves a place in Arizona, a gesture of isolation in itself, although I always pictured Harry summoning Air Force One to whisk him to work. If dull company was a problem for Clare in New York, one imagined a plague-sized epidemic in Phoenix. But my parents who saw them periodically out there reported an unprecedented serenity on Clare's part. She was doing ceramics and painting and a column for McCall's: the usual buzz of hobbies. In fact, she worked very hard at her Art, just in case America needed a great painter in a hurry (actually she doesn't have to excel to enjoy doing something). And she was also at some point taking LSD, which can account for a lot of serenity, if it hits you right.

At that time, LSD was almost unknown, so it is nice to think of the Luces blazing a trail for later hippies to follow. The effects on both were benign, and Harry actually strolled out into the backyard (or back ranch) one night conducting an invisible symphony orchestra. Another time he claimed to have talked to God on the golf course, and found that the Old Boy seemed to be on top of things and knew pretty much what He was doing. The old prickly pear had found the right medicine. Clare was equally euphoric, and characteristically tried to pass on the discovery to others, including my mother, a stately but adventurous woman, who would try anything, or at least think of trying anything. She finally refrained because of the coincidental heart attacks of two previous converts, the afore-mentioned Fathers Murray and Weigel. A courtly little group of acid droppers if there ever was one, out there in the desert.

"LSD saved our marriage" would be putting it too strongly, but it may have made it a little mellower. Harry had gone through a somewhat restless, tossing-and-turning mid-life, in the course of which in 1959 he had made marrying noises in the direction of one Lady Jean Campbell, the granddaughter of Lord Beaverbrook, the British press baron. Clare knew she herself had few wifely claims on Harry, and has always been very understanding in sexual matters, but she was embarrassed to tears over Harry, who appeared to be making an ass of himself, and tangentially herself. (Harry's other wife, Time Inc., felt roughly the same way.)

The best name for her feeling is probably simple confusion. Lady Jean was the least likely suspect, a young girl they'd befriended as a favor to the Beaver, and who had stayed with both of them in the Bahamas a couple of years before, practically a ward of the family, and by the Luces' standards a bit of a toper. Clare had never guessed (and she guessed many things) that anything like this was even possible. Her public response was a superb example of grace under pressure (which is actually the definition of wit, not courage at all). She said, "If Jean marries Henry and I marry Lord Beaverbrook, then I'll be Harry's grandmother."

(7) Gaeton Fonzi, The Last Investigation (1993)

One of the first leads Schweiker asked me to check came from a source he considered impeccable: Clare Boothe Luce. One of the wealthiest women in the world, widow of the founder of the Time, Inc. publishing empire, former member of the U.S. House of Representatives, former Ambassador to Italy, successful Broadway playwright, international socialite and longtime civic activist, Clare Boothe Luce was the last person in the world Schweiker would have suspected of leading him on a wild goose chase.

Yet the chase began almost immediately. Right after Schweiker announced the formation of his Kennedy Assassination Subcommittee, he was visited by Vera Glaser, a syndicated Washington columnist. Glaser told him she had just interviewed Clare Boothe Luce and that Luce had given her some information relating to the assassination. Schweiker immediately called Luce and she, quite cooperatively and in detail, confirmed the story she had told Glaser.

Luce said that some time after the Bay of Pigs she received a call from her "great friend" William Pawley, who lived in Miami. A man of immense wealth-he had made his millions in oil-during World War II Pawley had gained fame setting up the Flying Tigers with General Claire Chennault. Pawley had also owned major sugar interests in Cuba, as well as Havana's bus, trolley and gas systems and he was close to both pre-Castro Cuban rulers, President Carlos Prio and General Fulgencio Batista. (Pawley was one of the dispossessed American investors in Cuba who early tried to convince Eisenhower that Castro was a Communist and urged him to arm the exiles in Miami.)

Luce said that Pawley had gotten the idea of putting together a fleet of speedboats-sea-going "Flying Tigers" as it were-which would be used by the exiles to dart in and out of Cuba on "intelligence gathering" missions. He asked her to sponsor one of these boats and she agreed. As a result of her sponsorship, Luce got to know the three-man crew of the boat "fairly well," as she said. She called them "my boys" and said they visited her a few times in her New York townhouse. It was one of these boat crews, Luce said, that originally brought back the news of Russian missiles in Cuba. Because Kennedy didn't react to it, she said she helped feed it to Senator Kenneth Keating, who made it public. She then wrote an article for Life magazine predicting the missile crisis. "Well, then came the nuclear showdown and the President made his deal with Khrushchev and I never saw my young Cubans again," she said. The boat operations were stopped, she said, shortly afterwards when Pawley was notified that the U.S. was invoking the Neutrality Act and would prevent any further exile missions into Cuba.

Luce said she hadn't thought about her boat crew until the day that President Kennedy was killed. That evening she received a telephone call from one of the crew members. She told Schweiker his name was "something like" Julio Fernandez, and he said he was calling her from New Orleans. Julio Fernandez told her that he and the other crew members had been forced out of Miami after the Cuban missile crisis and that they had started a "Free Cuba" cell in New Orleans. Luce said that Fernandez told her that Oswald had approached his group and offered his services as a potential Castro assassin. He said his group didn't believe Oswald, suspected he was really a Communist and decided to keep tabs on him. Fernandez said they found that Oswald was, indeed, a Communist, and they eventually penetrated his "cell" and tape-recorded his talks, including his bragging that he could shoot anyone because he was "the greatest shot in the world with a telescopic lens." Fernandez said that Oswald then suddenly came into money and went to Mexico City and then Dallas. According to Luce, Fernandez also told her that his group had photographs of Oswald and copies of handbills Oswald had been distributing on the streets of New Orleans. Fernandez asked Luce what he should do with this information and material.

(8) John Ranelagh, The Agency: The Rise and Decline of the CIA (1986)

The nature of Arbenz's government, however, meant that Operation Success launched both the CIA and the United States on a new path. Mussadegh in Iran was left-wing and had indulged in talks with Russian diplomats about possible alliances and treaties. Arbenz, on the other hand, had simply been trying to reform his country and had not sought foreign help in this. Thus by overthrowing him, America was in effect making a new decision in the cold war. No longer would the Monroe Doctrine, which was directed against foreign imperial ambitions in the Americas from across the Atlantic or the Pacific, suffice. Now internal subversion communism from within - was an additional cause for direct action. What was not said, but what was already clear after the events in East Germany the previous year, was that the exercise of American power, even clandestinely through the CIA, would not be undertaken where Soviet power was already established. In addition, regardless of the principles being professed, when direct action was taken (whether clandestine or not), the interests of American business would be a consideration: if the flag was to follow, it would quite definitely follow trade.

The whole arrangement of American power in the world from the nineteenth century was based on commercial concerns and methods of operation his had given America a material empire through the ownership of foreign transport systems, oil fields, stocks, and shares. It had also given America resources and experience (concentrated in private hands) with the world outside the Americas, used effectively by the OSS during World War II American government, however, had stayed in America, lending its influence to business but never trying to overthrow other governments for commercial purposes. After World War II, American governments were more willing to use their influence and strength all over the world for the first time and to see an ideological implication in the "persecution" of U.S. business interests.

(9) Lisa Pease, Probe Magazine (March-April, 1996)

During the Church committee hearings, Senator Richard Schweiker's independent investigator Gaeton Fonzi stumbled onto a vital lead in the Kennedy assassination. An anti-Castro Cuban exile leader named Antonio Veciana was bitter about what he felt had been a government setup leading to his recent imprisonment, and he wanted to talk. Fonzi asked him about his activities, and without any prompting from Fonzi, Veciana volunteered the fact that his CIA handler, known to him only as "Maurice Bishop," had been with Lee Harvey Oswald in Dallas not long before the assassination of Kennedy. Veciana gave a description of Bishop to a police artist, who drew a sketch. One notable characteristic Veciana mentioned were the dark patches on the skin under the eyes. When Senator Schweiker first saw the picture, he thought it strongly resembled the CIA's former Chief of the Western Hemisphere Division-one of the highest positions in the Agency - and the head of the Association of Former Intelligence Officers (AFIO): David Atlee Phillips.