Harry Bridges

Alfred Renton (Harry) Bridges, the son of realtor, was born on 28th July, 1901 in Melbourne, Australia. After leaving school he worked for his father but after reading the work of Jack London, he decided to become a sailor.

While working on a ship travelling to Tasmania he came into contact with members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Formed in 1905, IWW's goal was to promote worker solidarity in the revolutionary struggle to overthrow the employing class. Its motto was "an injury to one is an injury to all". During this period he became a socialist. This was reinforced by the poverty he witnessed on his travels. He later wrote: “the more I saw the more I knew that there was something wrong with the system”.

In 1920 Bridges moved to San Francisco where he worked for a time as a sailor until becoming a longshoreman. Ella Winter wrote about the situation in her book, And Not to Yield (1963): "Every morning longshoremen had to line up on the dock and wait to see if they would be chosen, and if there was not enough work to go around, they went home empty-handed to their wives. There was no security of income, however small, and the indignity in addition incensed as well as humiliated them. Exasperated hatred and competitiveness replaced what should have been the comradeship of work and the solidarity of workingmen fighting together for their common interests."

As Michael Reagan has pointed out in his article, Harry Bridges: Life and Legacy (2010): "There was no regular work, and to get a job workers had to subject themselves to the hated shape-up. Early each morning those seeking employment would gather at dock gates to be selected individually for that day’s work. The throngs of people looking for work at the gates meant employers could fire any individual at any time without fear of loosing a minute of work for the day." Bridges joined the International Longshoremen's Association.

He was active in what became known as the Albion Hall faction. It was claimed that this group included members of the American Communist Party. During this period he was quoted as saying: "There will always be a place for us somewhere, somehow, as long as we see to it that working people struggle on, fight for everything they have, everything they hope to get, for dignity, equality, democracy, to oppose war and to bring to the world a better life."

Griffin Fariello has argued: "In 1929, freight tonnage in and out of the Golden Gate amounted to more than 31 million tons. San Francisco shipping and stevedoring companies took pride that San Francisco had one of the most cost-efficient longshore workforces in the country. A gang of sixteen men could move - by hand - upwards of twenty tons an hour, and a crew of a hundred men could load a three-thousand ton steamer in just two days and a night, stowing enough cargo to fill a train of freight cars five miles long. The American-Hawaiian Steamship Company calculated that during the years 1927-1931 their agents paid, on average, $0.99-1.03 per ton for loading in San Francisco, compared to $1.85-1.99 in New York and $2.17-2.43 in Boston. But the port of San Francisco was also known for the worst working conditions in the world - and the deadliest."

On 13th June, 1933, the Senate passed the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) by a vote of 46 to 37. The National Recovery Administration (NRA) was set up to enforce the NIRA. President Franklin D. Roosevelt named Hugh S. Johnson to head it. The NIRA allowed industry to write its own codes of fair competition but at the same time provided special safeguards for labor. Section 7a of NIRA stipulated that workers should have the right to organize and bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing and that no one should be banned from joining an independent union. The NIRA also stated that employers must comply with maximum hours, minimum pay and other conditions approved by the government. Bridges and other members of the Albion Hall faction decided to use the legislation to gain union representation.

On 9th May 1934, the International Longshoremen's Association went on strike in order to obtain a thirty-hour week, union recognition and a wage increase. A federal mediating team, led by Edward McGrady, worked out a compromise. Joseph P. Ryan, president of the union, accepted it, but the rank and file, influenced by Harry Bridges, rejected it.

In San Francisco the vehemently anti-union Industrial Association, an organization representing the city's leading industrial, banking, shipping, railroad and utility interests, decided to open the port by force. This resulted in considerable violence and on 13th July, Bridges appealed to other union members to join the strike. Michael Casey, president of Teamsters 85, said: "In all my thirty years of leading these men, I have never seen them so worked up, so determined to walk out. I don't believe any power on earth can prevent them going on strike unless the maritime strike is settled."

Ella Winter went to interview Harry Bridges during the dispute: "In San Francisco I went first to the longshoremen's headquarters on the Embarcadero and found Harry Bridges, the voluble and tough union leader, a wire spring of a man with a narrow, sharp-featured, expressive face, popping eyes, and strong Australian accent. He heartily greeted a fellow Australian, a limey, as he dubbed me, though I was a little taken aback at my first real taste of a worker's intemperate language."

Bridges told her that previous strikes had been crushed and a company union set up: "The seamen couldn't get together because they were divided into so many crafts, machinists, cooks, stewards, ships' scalers, painters, boilermakers, the warehousemen on the docks, and the teamsters who hauled the goods. The bosses want to keep it that way so they can make separate contracts for each craft and in each port, which weakens our bargaining position. We're asking for one coastwise contract, from Portland to San Pedro, for the whole industry, and a raise too, but the most important thing we want is a hiring hall under the men's control."

Hugh S. Johnson visited the city where he spoke to John Francis Neylan, chief counsel for the Hearst Corporation, and the most significant figure in the Industrial Association. Neylan convinced Johnson that the general strike was under the control of the American Communist Party and was a revolutionary attack against law and order. Johnson later wrote: "I did not know what a general strike looked like and I hope that you may never know. I soon learned and it gave me cold shivers."

On 17th July 1934 Johnson gave a speech to a crowd of 5,000 assembled at the University of California, where he called for the end of the strike: "You are living here under the stress of a general strike... and it is a threat to the community. It is a menace to government. It is civil war... When the means of food supply - milk to children, necessities of life to the whole people - are threatened, that is bloody insurrection... I am for organized labor and collective bargaining with all my heart and soul and I will support it with all the power at my command, but this ugly thing is a blow to the flag of our common country and it has to stop.... Insurrection against the common interest of the community is not a proper weapon and will not for one moment be tolerated by the American people who are one - whether they live in California, Oregon or the sunny South."

Johnson's speech inspired local right-wing groups to take action against the strikers. Union offices and meeting halls were raided, equipment and other property destroyed, and communists and socialists were beaten up. Johnson further inflamed the situation when he turned up for a meeting with John McLaughlin, the secretary of the San Francisco Teamsters Union, on 18th July, drunk. Instead of entering into negotiations, he made a passionate speech attacking trade unions. McLaughlin stormed out of the meeting and the strike continued.

The famous journalist, Lincoln Steffens, supported the strikers. On 19th July 1934 he wrote to Frances Perkins, the Secretary of Labor: "There is hysteria here, but the terror is white, not red. Business men are doing in this Labor struggle what they would have liked to do against the old graft prosecution and other political reform movements, yours included... Let me remind you that this widespread revolt was not caused by aliens. It takes a Chamber of Commerce mentality to believe that these unhappy thousands of American workers on strike against conditions in American shipping and industry are merely misled by foreign Communist agitators. It's the incredibly dumb captains of industry and their demonstrated mismanagement of business that started and will not end this all-American strike and may lead us to Fascism."

In order to bring an end to the dispute, both sides agreed to arbitration. It was not until October, 1934, that an agreement was reached. Wages and working conditions were improved, the agreement established coast-wide bargaining and a joint employer and union hiring hall that would end the shape-up system. Harry Bridges was rewarded for his leadership of the strike by being elected president of the San Francisco local in 1935 and then president of the Pacific Coast District of the ILA in 1936.

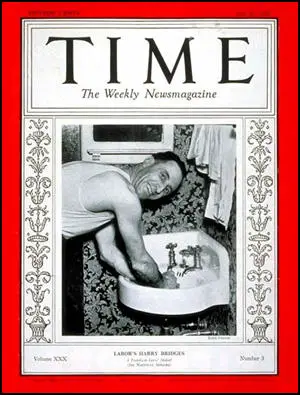

In 1937, Bridges was elected president of the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union (ILWU). Bridges arranged for it to be affiliated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). John L. Lewis now appointed Bridges as the West Coast Director for the CIO. By this time Bridges was one of the best known trade union leaders in the country and on 19th July, 1937, he appeared on the front cover of Time Magazine.

Bridges was known for his great charm and became friends with the aspiring politician, Clare Luce, the wife of Henry Luce, the highly successful magazine publisher. Clare later admitted that he nearly converted her to Marxism: "I suspect now that the appeal of Communism for many young people and for me lay in its religious aspect. Communism was a complete, authoritarian religious structure, and the liberal mind had grown weary and confused defending the inalienable right to disorganize and exploit society according to its own notions of liberty. This had led to Hooverism and rugged individualism."

During the 1930s Bridges was associated with progressive causes. As Griffin Fariello explained: "Throughout it's history the ILWU has held to the belief that only in a stable, secure, and peaceful world can social and economic justice be achieved for all. Accordingly, in the 1930s, the union blocked the shipment of supplies to the rising fascist nations in Europe and Asia, and supported the fledgling Republic of Spain in its uneven struggle against the Axis powers. In 1938, they refused to load scrap iron destined for Japan and presciently claimed the iron would return as bombs against the United States."

After the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact in 1939 Bridges attacked President Franklin D. Roosevelt for wanting to go to war against Nazi Germany. He adopted the slogan "The Yanks Ain't Coming" in his campaign to keep the United States out of the European war. The head of the CIO, John L. Lewis, was a supporter of intervention and removed Bridges as West Coast director of the organization. Bridges also upset other union members when he campaigned against Roosevelt in the 1940 Presidential Election.

The Alien Registration Act (also known as the Smith Act) was passed by Congress on 29th June, 1940, made it illegal for anyone in the United States to advocate, abet, or teach the desirability of overthrowing the government. The law also required all alien residents in the United States over 14 years of age to file a comprehensive statement of their personal and occupational status and a record of their political beliefs. Within four months a total of 4,741,971 aliens had been registered. In 1941 Bridges was arrested under the terms of the act and attempts were made to deport him for being a member of the American Communist Party. Bridges denied the charges and was eventually released.

Bridges changed his view on the Second World War after Adolf Hitler ordered the attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941. Bridges now called on President Franklin D. Roosevelt to declare war and after Pearl Harbor adopted a wartime no-strike pledge. Bridges also called on his members to increase production without extra pay. He also condemned Retail, Wholesale Department Store Employees Union for going on strike at Montgomery Ward in 1943. Bridges also supported a proposal by Roosevelt in 1944, to militarize some civilian workplaces.

After the Second World War it was now decided to use the Alien Registration Act against the leaders of the ACP. On the morning of 20th July, 1948, Eugene Dennis, the general secretary of the ACP, and eleven other party leaders, included William Z. Foster, Benjamin Davis, John Gates, Robert G. Thompson, Gus Hall, Benjamin Davis, Henry M. Winston and Gil Green were arrested and charged under the Alien Registration Act. After a nine month trial they were found guilty of violating the Alien Registration Act and sentenced to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine. Thompson, because of his war record, received only three years.

Bridges was now arrested and tried for fraud and perjury for denying when applying for naturalization that he had ever been a member of the American Communist Party. The jury convicted Bridges and he was sentenced to five years in prison and his citizenship was revoked. The Supreme Court in a 5-3 decision overturned the conviction in 1953 because the indictment on fraud and perjury charges did not occur within the three years set by the statute of limitations.

In 1958 Harry Bridges decided to marry Noriko Sawada, a Nisei Japanese American, in Reno, Nevada. When the court clerk denied them a marriage license on the grounds that it violated the state’s anti-miscegenation law, the couple challenged the law in the courts. They won, and were married at the end of the year. This case prompted the Nevada legislature to repeal the state's anti-miscegenation laws on 17th March, 1959.

Despite attempts to remove him, Bridges remained head of the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union (ILWU) until his retirement aged 76 in 1977.

Harry Bridges died in San Francisco, aged 88, on 30th March, 1990.

© John Simkin, May 2013

Primary Sources

(1) Michael Reagan, Harry Bridges: Life and Legacy (2010)

In 1920 Bridges moved permanently to San Francisco where he worked for a time as a sailor until the AFL affiliated Sailors Union of the Pacific was crippled in a 1921 strike. It was at this point that he began longshoring on the San Francisco docks. There was no regular work, and to get a job workers had to subject themselves to the hated shape-up. Early each morning those seeking employment would gather at dock gates to be selected individually for that day’s work. The throngs of people looking for work at the gates meant employers could fire any individual at any time without fear of loosing a minute of work for the day. Bridges recalled the shape-up felt “more or less like a slave market in the Old World countries of Europe.” Employers also used a company union to control and retaliate against the workforce through a “Blue Book” whereby a worker’s history was recorded. A clean book was necessary to get hired, and the system was used to expel pro-union workers.

After avoiding the company union for a period and working free-lance to support his wife and children, Bridges joined the International Longshoremen’s Association when a west coast charter was granted in the early ‘30s. He quickly started working with the Albion Hall faction within the union, a rank and file group with communist influences. When the Roosevelt administration made it clear that they would back unionization through enforcement of section 7a of the National Industrial Recovery Act, Bridges and like-mined unionists used the opportunity to push for authentic union representation. In March of 1934 the ILA membership voted overwhelmingly to strike. Their demands included union recognition, an end to the shape-up through a union hiring hall, and a coast-wide contract. After some back and forth with employers, longshoremen walked off their jobs on May 9th.

(2) Ella Winter, And Not to Yield (1963)

Every morning longshoremen had to line up on the dock and wait to see if they would be chosen, and if there was not enough work to go around, they went home empty-handed to their wives. There was no security of income, however small, and the indignity in addition incensed as well as humiliated them. Exasperated hatred and competitiveness replaced what should have been the comradeship of work and the "solidarity" of workingmen fighting together for their common interests. "That's the only weapon we have," one or another would comment as they listened to Bridges tell me, "standing together."

This strike became the biggest in American maritime history, with fourteen thousand men idle. Stevedoring up and down the coast practically ceased; at the height of the battle, a hundred ships rode at anchor at their moorings in San Francisco Bay. The struggle lasted for months. As it continued week after week, shipowners grew as incensed as the Associated Farmers had been, and as violent. Strikers were clubbed, beaten, and gassed; every means was used to bring them to heel, including promises from officials, not quite honest offers from the Eastern union leader Joseph P. Ryan, who was then booed out of the city. The Red scare was brandished, until the simplest longshoreman could be accused of "treason," "conspiracy," "overthrow of the government," "attacks on constituted authority." "It isn't a strike at all" was the main contention of the Industrial Association. "Labor is seeking government control." Inflamed headlines kept the populace at fever point.

Talk grew of a general strike. There had been only one previously in United States history, in Seattle in 1926, and that had failed. Now, after an unsuccessful attempt to open one port, Portland, by force, troops were called out in San Francisco, and police staged a pitched battle, known as the "Battle of Rincon Hill." Workers were chased with clubs and guns, even machine guns, and two fleeing men were shot and killed. One, Howard Sperry, was a veteran, and Nicholas Bordoise, a Greek cook, was on his way home after cooking for the pickets on the Embarcadero. A doctor friend who attended the wounded in prison said it was "like an assault in wartime." And all day the police cars tore through the echoing streets, their sirens screaming.

(3) Griffin Fariello, The Life and Times of Harry Bridges (1990)

By the beginning of 1934 Harry Bridges found himself at the head of the Albion Hall group of labor activists. Named for the rented hall in which they met, these men had put in years of organizing, working to establish the International Longshoremen's Association (I.L.A.) as a single unit along the entire West Coast. Many of the establishment leaders of the other city unions were wary of Harry and his group, but their own rank and file backed the straight-talking Australian. This was no more evident than with the Teamsters, who were crucial to the success of the longshoremen as it was they who hauled the freight to and from the docks. The waterfront was rife with tension. Talk of a general strike was in the air.

On May 9, 1934, after a month of fruitless negotiations, the longshoremen struck for recognition. The Teamsters joined in and every port on the west coast shut down. Not long after, the beleaguered seagoing unions joined the strike. The seamen also worked under terrible conditions. With the coming of the Great Depression, the shipping companies had seized the opportunity to squeeze out even more profits. Even though the construction of their fleets had been ninety percent subsidized by taxpayers, and even though they received additional millions of dollars yearly through the carrying of U.S. mail overseas, the shipowners took advantage of the sudden pool of unemployed. To the critics of these subsidies they had claimed the necessity of paying "good American wages," yet they now drove these wages down so steeply that desperate seamen were forced to pay $5 and up for jobs that paid one-cent-a-month plus room and board. The jobs were called "workaways." They worked 16 and 18 hour shifts, and the food was so bad it reportedly would sicken a goat.

This was the first industry-wide strike in history. It was unionism built by the members and a strike run by the members. Contributions flooded in from every direction Ð from unions, organizations, and private individuals up and down the coast. Farmers sent truckloads of produce to the striker's relief kitchens.

The ship owners and their allies were also prepared. They believed this was the opportunity to deliver the final blow to organized labor on the docks. Banker William H. Crocker called it "the best thing that ever happened to San Francisco. It's costing us money, certainly. But it's a good investment, a marvelous investment. It's solving the labor problem for years to come, perhaps forever. When the men have been driven back to their jobs, we won't have to worry about them anymore. They'll have learned their lesson. Labor in San Francisco is licked."

The waterfront employers attempted to recruit replacement workers from the African-American community, a group long marginalized on the waterfront. This was the traditional method to break a strike, pit worker against worker along racial lines. But they soon discovered that Harry had been there before them. He had gone to the churches and the meeting halls. He had acknowledged the injustices that had plagued that community for so long and promised that in this new union he was fighting to create there would be no color line. The union would open full membership to African-Americans based not on the hue of their skin but solely on the strength of their hearts for the struggle ahead. "All workers must stand together," he told them. "There can be no discrimination because of race, color, creed, national origin, religious or political belief. Discrimination is the weapon of the boss."

There was no lack of heart. During the hard months ahead, the African-American community stood by the longshoremen and the longshoremen stood by their promise. A promise that is enshrined in the constitution of the I.L.W.U. and is fiercely defended to this day.

Arrayed against the strikers were the shipowners, the Associated Farmers of California, the Employers Industrial Associations up and down the coast, the American Legion, and several vigilante groups, which in connivance with the police and employers loosed a unrestrained reign of terror. Unionists were assaulted on the streets and in their homes, meeting halls were destroyed, organizations friendly to the strikers were raided and their members beaten. After one such raid on a small pro-union group, the hallways and staircases were found slippery with blood.

After more than two months of stalemate and several police attacks upon the strikers (including one in which 250 high school students were clubbed bloody on National Youth Day), the employers decided to open the docks. The key port of San Francisco was their target. If they could crush the revolt in San Francisco, then the coastwide strike would collapse.

What followed on the two days of July Third and Fifth was brutal street fighting between thousands of strikers and police Ð an uneven struggle, angry and bloody, pitting the fists and boots of unarmed union men against clubs and riot guns, nausea gas and revolvers. But it is the final day -- a desperate twelve hour battle that raged up and down the Embarcadero Ð that is now remembered as "Bloody Thursday."

That day began with the 5,000 striking workers lining the inland side of the Embarcadero, facing off the thousands of armed policemen and vigilantes who guarded the docks. Pier 38 was to be opened. Hot cargo waited on the trucks idling behind the metal gates of the pierhead. If that cargo could be moved to the warehouse just blocks away, then the employers could claim a victory. The longshoremen knew full well what that meant - their children would remain hungry, their wives old before their time, their own lives cut short and brutalized. They were determined never to see that day.

At eight AM, a prowl car pulled to a halt between the lines. A Police Captain rode the running boards. He called out, "Let'em have it, men!" The police emptied their riot and gas guns into the line of strikers. The unionists recoiled, but held their ranks. The next moment they surged forward and the battle was joined.

Witnesses of that day claim the men fought and fell in silence. The only sounds to be heard were the crack of clubs against skulls, the report of gunfire and exploding gas canisters, the wail of sirens. Scattered groups of men slugged it out against the swinging clubs, while others retreated under the onslaught only to regroup and join the fray again. Several hundred unionists were driven back up the slopes of Rincon Hill, then under preparation for construction of an anchorage for the Bay Bridge. There, the men threw up barricades from the debris of demolished buildings to protect themselves from gunfire. From their positions they hurled brickbats down the slope at the police.

Three assaults were mounted against the men on Rincon Hill. The first was a wave of policemen on foot, the second a charge on horseback. Both were driven back by the strikers. The third was also on horseback, but prepared for with a sustained volley of gunfire and a curtain of gas laid across the crest of the hill. The exploding canisters ignited the dry grasses and the slopes were soon a raging inferno. The horsemen pounded through smoke and gas to gain the heights. But when they leapt the barricade, there was not a striker in sight. They had simply slipped away. Police took command of the hill and surrounded it with guards to prevent recapture.

(4) Hugh S. Johnson, speech at the University of California (17th July 1934)

You are living here under the stress of a general strike... and it is a threat to the community. It is a menace to government. It is civil war... When the means of food supply - milk to children, necessities of life to the whole people - are threatened, that is bloody insurrection... I am for organized labor and collective bargaining with all my heart and soul and I will support it with all the power at my command, but this ugly thing is a blow to the flag of our common country and it has to stop.... Insurrection against the common interest of the community is not a proper weapon and will not for one moment be tolerated by the American people who are one - whether they live in California, Oregon or the sunny South.

(5) Michael Reagan, Harry Bridges: Life and Legacy (2010)

There was no regular work, and to get a job workers had to subject themselves to the hated shape-up. Early each morning those seeking employment would gather at dock gates to be selected individually for that day’s work. The throngs of people looking for work at the gates meant employers could fire any individual at any time without fear of loosing a minute of work for the day.

(6) Harry Bridges, interviewed by Ella Winter (1934)

The seamen couldn't get together because they were divided into so many crafts, machinists, cooks, stewards, ships' scalers, painters, boilermakers, the warehousemen on the docks, and the teamsters who hauled the goods. The bosses want to keep it that way so they can make separate contracts for each craft and in each port, which weakens our bargaining position. We're asking for one coastwise contract, from Portland to San Pedro, for the whole industry, and a raise too, but the most important thing we want is a hiring hall under the men's control.