United Nations

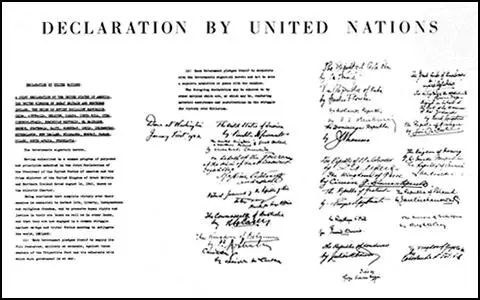

On 1st January 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, supported by the representatives of 26 countries, published the Declaration by United Nations, a document that pledged their governments to continue fighting together against Nazi Germany and Japan during the Second World War.

This declaration was followed by a conference of Foreign Ministers in Moscow, in October, 1943 where discussions took place concerning a replacement for the discredited League of Nations.

Further talks took place at San Francisco between 15th April and 26th June, 1945. Delegates from fifty nations that had been at war with Germany, decided on the design and structure of this new organization. The conference drafted the United Nations Charter and it was signed on 26th June and ratified at the first session of the General Assembly of the United Nations in London on 24th October 1945.

The main differences between the League of Nations and the United Nations were the stronger executive powers assumed by the Security Council and the requirement that member states should make available armed forces to serve as peace-keepers or to repel an aggressor.

The Security Council had five permanent members, United States, the Soviet Union, China, France and Britain. Six other countries served two-year periods on the Council (this was increased to ten in 1965). Controversially, permanent members were given the power to veto decisions made by the Security Council. The other nations vigorously opposed the idea of the veto but it became clear that without such a favoured position the five major nations would not join the United Nations. The United States Senate ratified the United Nations treaty by a vote of 89 to 2 on 28th July, 1945.

Primary Sources

(1) Anthony Eden, telegram to Winston Churchill (March, 1943)

The first point raised by the President was the structure of the United Nations organization after the war. The general idea is that there should be three organizations. The first would be a general assembly at which all the United Nations would be represented. This assembly would only meet about once a year and its purpose would be to enable representatives of all the smaller powers to blow off steam. At the other end of the scale would be an executive committee composed of representatives of the Four Powers. This body would take all the more important decisions and wield police powers of the United Nations. In between these two bodies would be an advisory council composed of representatives of the Four Powers and of, say, six or eight other representatives elected on a regional basis, roughly on the basis of population. There might thus be one representative from Scandinavia and Finland and one or two from groups of Latin American states. This council would meet from time to time as might be required to settle any international questions that might be brought before it.

The President said it was essential to include China among the Four Powers and to organize all these United Nations organs on a worldwide and not on a regional basis. He made it clear that the only appeal which would be likely to carry weight with the United States public, if they were to undertake international responsibilities, would be one based upon a worldwide conception. They would be very suspicious of any organization that was only regional. We have strong impression that it is through their feeling for China that the President is seeking to lead his people to accept international responsibilities.

(2) Anthony Eden, memorandum to Duff Cooper (25th July, 1944)

There is no doubt that, rightly or wrongly, the American Administration is suspicious of proposals which tend, in their opinion, to divide up the world into a series of blocs. Not only do they fear that such blocs would become mutually hostile, but they also believe that their formation would tend to reinforce those isolationist elements in the United States who are above all anxious that their country should undertake no commitments in Europe, but rather concentrate on preserving its power and influence in South America, and possibly in the Far East as well.

Only by encouraging the formation of some World Organization are we likely to induce the Americans, and this means the American Senate, to agree to accept any European commitments designed to range America, in case of need, against a hostile Germany or against any European breaker of the peace.

(3) Conversation between Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin at Yalta about the possibility of establishing the United Nations.

Winston Churchill: "The peace of the world depends upon the lasting friendship of the three great powers, but His Majesty's Government feel we should be putting ourselves in a false position if we put ourselves in the position of trying to rule the world when our desire is to serve the world and preserve it from a renewal of the frightful horrors which have fallen upon the mass of its inhabitants. We should make a broad submission to the opinion of the world within the limits stated. We should have the right to state our case against any case stated by the Chinese, for instance, in the case of Hong Kong. There is no question that we could not be required to give back Hong Kong to the Chinese if we did not feel that was the right thing to do. On the other hand, I feel it would be wrong if China did not have an opportunity to state its case fully. In the same way, if Egypt raises a question against the British affecting the Suez Canal, as has been suggested, I would submit to all the procedure outlined in this statement. Colleagues on the Security Council."

Joseph Stalin: "I would like to have this document to study because it is difficult on hearing it read to come to any conclusion. I think that the Dumbarton Oaks decisions have, as an objective, not only to secure to every nation the right to express its opinion, but if any nation should raise a question about some important matter, it raises the question in order to get a decision in the matter. I am sure none of those present would dispute the right of every member of the Assembly to express his opinion. "Mr. Churchill thinks that China, if it raised the question of Hong Kong, would be content only with expressing opinion here. He may be mistaken. China will demand a decision in the matter and so would Egypt. Egypt will not have much pleasure in expressing an opinion that the Suez Canal should be returned to Egypt, but would demand a decision on the matter. Therefore, the matter is much more serious than merely expressing an opinion. Also, I would like to ask Mr. Churchill to name the power which may intend to dominate the world. I am sure Great Britain does not want to dominate the world. So one is removed from suspicion. I am sure the United States does not wish to do so, so another is excluded from the powers having intentions to dominate the world."

Winston Churchill: "May I answer?"

Joseph Stalin: "In a minute. When will the great powers accept the provisions that would absolve them from the charge that they intend to dominate the world ? I will study the document. At this

time it is not very clear to me. I think it is a more serious question than the right of a power to express its intentions or the desire of some power to dominate the world."

Winston Churchill: "I know that under the leaders of the three powers as represented here we may feel safe. But these leaders may not live forever. In ten years' time we may disappear. A new generation will come which did not experience the horrors of war and may probably forget what we have gone through. We would like to secure the peace for at least fifty years. We have now to build up such a status, such a plan, that we can put as many obstacles as possible to the coming generation quarreling among themselves."

(4) Anthony Eden wrote about Yalta in his autobiography, Memoirs: The Reckoning (1965)

Roosevelt was, above all else, a consummate politician. Few men could see more clearly their immediate objective, or show greater artistry in obtaining it. As a price of these gifts, his long-range vision was not quite so sure. The President shared a widespread American suspicion of the British Empire as it had once been and, despite his knowledge of world affairs, he was always anxious to make it plain to Stalin that the United States was not 'ganging up' with Britain against Russia. The outcome of this was some confusion in Anglo-American relations which profited the Soviets.

Roosevelt did not confine his dislike of colonialism to the British Empire alone, for it was a principle with him, not the less cherished for its possible advantages. He hoped that former colonial territories, once free of their masters, would become politically and economically dependent upon the United States, and had no fear that other powers might fill that role.

Winston Churchill's strength lay in his vigorous sense of purpose and his courage, which carried him undismayed over obstacles daunting to lesser men. He was also generous and impulsive, but this could be a handicap at the conference table. Churchill liked to talk, he did not like to listen, and he found it difficult to wait for, and seldom let pass, his turn to speak. The spoils in the diplomatic game do not necessarily go to the man most eager to debate.

Marshal Stalin as a negotiator was the toughest proposition of all. Indeed, after something like thirty years' experience of international conferences of one kind and another, if I had to pick a team for going into a conference room, Stalin would be my first choice. Of course the man was ruthless and of course he knew his purpose. He never wasted a word. He never stormed, he was seldom even irritated. Hooded, calm, never raising his voice, he avoided the repeated negatives of Molotov which were so exasperating to listen to. By more subtle methods he got what he wanted without having seemed so obdurate.

There was a confidence, even an intimacy, between Stalin and Molotov such as I have never seen between any other two Soviet leaders, as if Stalin knew that he had a valuable henchman and Molotov was confident because he was so regarded. Stalin might tease Molotov occasionally, but he was careful to uphold his authority. Only once did I hear Stalin speak disparagingly of his judgment and that was not before witnesses.

(5) Joseph Goebbels, diary entry (3rd April, 1945)

As far as the political crisis of the war is concerned dissatisfaction with the Kremlin's policy is increasing among the American public. The San Francisco Conference is already written off almost everywhere. It is hoped to substitute a new Three-Power meeting for it. No one knows, however, whether Stalin will agree to this. Stalin is treating Roosevelt and Churchill like dunces and it is only to be hoped that this sort of provocation will gradually make the pot boil over in the Western enemy camp.

As far as the San Francisco Conference is concerned, it is already a thing of the past. It is thought that Churchill intends to fly to Moscow again to try to persuade Stalin to give way. The progress of the political crisis among our enemies depends on the next fortnight's developments. The main and deciding factor is whether we succeed in organising some form of resistance in the West again.

The Jews have applied for a seat at the San Francisco Conference. It is characteristic that their main demand is that anti-semitism be forbidden throughout the world. Typically, having committed the most terrible crimes against mankind, the Jews would now like mankind to be forbidden even to think about them.

(6) Joseph Goebbels, diary entry (4th April, 1945)

Smuts has made an extraordinarily gloomy speech at the Imperial Conference now sitting in London. He regards San Francisco as the last chance for civilised mankind. If San Francisco fails, then what we regard as cultured mankind would be doomed. A human catastrophe of unimaginable proportions would be the inevitable result. A third world war would be waged with new and even more devastating weapons. What remained of mankind would be neither worthy nor capable of existence.

(7) James F. Byrnes, US Secretary of State, wrote about the formation of the United Nations in his autobiography Speaking Frankly (1947)

This generation of Americans has learned that the United States is a principal trustee of the world's peace and freedom. What the United States says and does affects the lives of people in the most remote areas of this earth. The words and deeds of a member of the Cabinet or of the Congress often reaches into more homes than those of many Kings and Presidents. Even Generalissimo Stalin, in his last talks with Harry Hopkins, acknowledged the world-wide interests and responsibilities of the United States and declared that our country has more reason to be a world power than any other.

Leadership and its inherent responsibilities we have accepted with reluctance-reluctance that two costly wars have not wholly overcome. But without our initiative, the United Nations probably would not have been created to promote and maintain international peace and security. Without our determined effort, it is doubtful whether ravages of war can be removed quickly enough to give the United Nations a chance to work.

The responsibilities that clearly are ours will be discharged in the years ahead only if we develop in international affairs a policy that truly reflects the will of our people. I am convinced that to build a people's foreign policy we must pursue three primary objectives.

(8) Adlai Stevenson, speech, Springfield (24th October, 1952)

But I do not believe it is man's destiny to compress this once boundless earth into a small neighborhood, the better to destroy it. Nor do I believe it is in the nature of man to strike eternally at the image of himself, and therefore of God. I profoundly believe that there is on this horizon, as yet only dimly perceived, a new dawn of conscience. In that purer light, people will come to see themselves in each other, which is to say they will make themselves known to one another by their similarities rather than by their differences. Man's knowledge of things will begin to be matched by man's knowledge of self. The significance of a smaller world will be measured not in terms of military advantage, but in terms of advantage for the human community. It will be the triumph of the heartbeat over the drumbeat.

These are my beliefs and I hold them deeply, but they would be without any inner meaning for me unless I felt that they were also the deep beliefs of human beings everywhere. And the proof of this, to my mind, is the very existence of the United Nations. However great the assaults on the peace may have been since the United Nations was founded, the easiest way to demonstrate the idea behind it is by the fact that no nation in the world today would dare to remove itself from membership and separate his country from the human hopes that are woven into the very texture of the organization.

The early years of the United Nations have been difficult ones, but what did we expect? That peace would drift down from the skies like soft snow? That there would be no ordeal, no anguish, no testing, in this greatest of all human undertakings?

Any great institution or idea must suffer its pains of birth and growth. We will not lose faith in the United Nations. We see it as a living thing and we will work and pray for its full growth and development. We want it to become what it was intended to be - a world society of nations under law, not merely law backed by force, but law backed by justice and popular consent. We believe the answer to world war can only be world law. This is our hope and our commitment, and that is why I join all Americans on this anniversary in saying: "More power to the United Nations."

(9) Konni Zilliacus, speech in the House of Commons (8th March, 1966)

This whole defence debate and the Defence White Paper are shot through with nostalgic illusions and nuclear and world military power hankerings and posturings ... The most depressing thing about the debate is the assumptions on both sides that we can go on indefinitely for years and years with the greatest, costliest and deadliest arms race in history. It will not work out like that and we must put our energy, will, purpose and policies into transferring the mutual relations of the great powers from the balance of power, as expressed in the rival military alliances, to their obligations, purposes and principles of the UN Charter ... We are no longer a first-class military power. But we could be a first-class political power and a first-class force for peace.