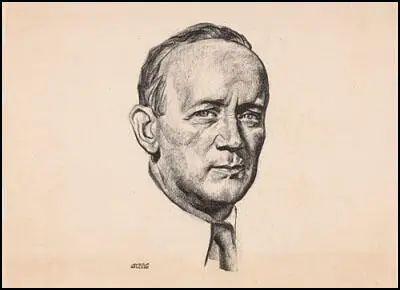

William Z. Foster

William Zebulon Foster was born in Taunton, Massachusetts, on 25th February, 1881. According to Theodore Draper: "His father, an English-hating Irish immigrant, washed carriages for a living. His mother, a devout Catholic of English-Scotch stock, bore twenty-three children, most of whom died; in infancy."

The family moved to Philadelphia in 1887. Foster later wrote that he grew up in a slum where "indolence, ignorance, thuggery, crime, disease, drunkenness and general social degeneration flourished." At the age of ten Foster was forced to leave school in search of work. After having several menial jobs in Pennsylvania he moved to New York City in 1900.

Foster joined the Socialist Party in 1901 and over the next few years worked as a cook, seaman, dock-worker, farm hand, trolley-car conductor, metal worker, car carpenter and airbrakeman. In 1904 he joined an extremist group headed by a physician, Dr. William F. Titus, "who preached an uncompromising version of faith in the revolutionary class struggle and scorn for all reforms." In 1910 he joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Foster was involved in the IWW free speech campaign and was imprisoned after a demonstration in Spokane.

Foster gradually emerged as was one of the leaders of the movement and in 1911 represented the IWW at the International Union Conference in Budapest. When Foster returned he argued that the IWW should disband so that its members could join and eventually capture the American Federation of Labour. When this was rejected, Foster left the IWW and formed the short-lived Syndicalist League of North America.

After the war, Foster, a railway car inspector in Chicago, joined the American Federation of Labour. He moved up the hierarchy and by 1920 he managed to persuade the AFL annual conference to pass a resolution in favour of government ownership of the railroads. The following year he supported John L. Lewis when he challenged Samuel Gompers for the presidency of the AFL.

In 1921 Earl Browder invited Foster to accompany him on a trip to Moscow to attend a conference of the Profintern. Foster was appointed the Profintern's agent in the United States and soon afterwards he joined the American Communist Party. At the time the party chairman was James Cannon, however, he was being challenged for this position by a group led by Charles Ruthenberg and Jay Lovestone. Foster initially associated himself with Cannon.

It was decided that because Foster had a strong following in the trade union movement that he should be the party candidate in the 1924 Presidential Election. Benjamin Gitlow was chosen as his running-mate. Foster did not do well and only won 38,669 votes (0.1 of the total vote). This compared badly with the other left-wing candidate, Robert La Follette, of the Progressive Party, who obtained 4,831,706 votes (16.6%).

The American Communist Party continued to be divided into two factions. One group that included Charles Ruthenberg, Jay Lovestone, Bertram Wolfe and Benjamin Gitlow, favoured a strategy of class warfare. Whereas Foster and James Cannon, believed that their efforts should concentrate on building a radicalised American Federation of Labor. Ruthenberg argued in an article published in Communist Labor: "The party must be ready to put into its program the definite statement that mass action culminates in open insurrection and armed conflict with the capitalist state. The party program and the party literature dealing with our program and policies should clearly express our position on this point. On this question there is no disagreement."

Foster retailated by arguing: "At heart and in their daily action the trade unions are revolutionary. Their unchangeable policy is to withhold from the exploiters all they have the power to. In these days, when they are weak in numbers and discipline, they have to content themselves with petty achievements. But they are constantly growing in strength and understanding, and the day will surely come when they will have the great masses of workers organized and instructed in their true interests. That hour will sound the death knell of capitalism. Then they will pit their enormous organization against the parasitic employing class, end the wages system forever and set up the long-hoped-for era of social justice. That is the true meaning of the trade union movement."

The Comintern eventually accepted the leadership of Charles Ruthenberg and Jay Lovestone. As Theodore Draper pointed out in American Communism and Soviet Russia (1960): "After the Comintern's verdict in favor of Ruthenberg as party leader, the factional storm gradually subsided.... At the Seventh Plenum at the end of 1926, the Comintern, for the first time in five years, found it unnecessary to appoint an American Commission to deal with an American factional struggle.... Ruthenberg's machine worked so smoothly and efficiently that it made those outside his inner circle increasingly restless. Beneath the surface of the factional lull, another rebellion smoldered, with the helpful encouragement of Cannon, who had touched off the anti-Ruthenberg rebellion three years earlier."

On the death of Charles Ruthenberg in 1927 Jay Lovestone became the party's national secretary. James Cannon, the chairman of the American Communist Party, attended the Sixth Congress of the Comintern in 1928. While in the Soviet Union he was given a document written by Leon Trotsky on the rule of Joseph Stalin. Convinced by what he read, when he returned to the United States he criticized the Soviet government. As a result of his actions, Cannon and his followers were expelled from the party. Cannon now joined with other Trotskyists to form the Communist League of America.

Foster, who remained a strong supporter of Joseph Stalin and remained in the American Communist Party and was their candidate in the 1928 Presidential Election. Once again Foster did badly and only won 48,551 votes (0.1%). This time it was Norman Thomas of the Socialist Party that was supported by left-wing voters.

On March 16, 1929, Benjamin Gitlow was appointed to the post of Executive Secretary of the party. Max Bedacht and Earl Browder made-up the three men leadership team. By this time Joseph Stalin had placed his supporters in most of the important political positions in the country. Even the combined forces of all the senior Bolsheviks left alive since the Russian Revolution were not enough to pose a serious threat to Stalin.

In 1929 Nikolay Bukharin was deprived of the chairmanship of the Comintern and expelled from the Politburo by Stalin. He was worried that Bukharin had a strong following in the American Communist Party, and at a meeting of the Presidium in Moscow on 14th May he demanded that the party came under the control of the Comintern. He admitted that Jay Lovestone was "a capable and talented comrade," but immediately accused him of employing his capabilities "in factional scandal-mongering, in factional intrigue." Benjamin Gitlow and Ella Reeve Bloor defended Lovestone. This angered Stalin and according to Bertram Wolfe, he got to his feet and shouted: "Who do you think you are? Trotsky defied me. Where is he? Zinoviev defied me. Where is he? Bukharin defied me. Where is he? And you? When you get back to America, nobody will stay with you except your wives." Stalin then went onto warn the Americans that the Russians knew how to handle troublemakers: "There is plenty of room in our cemeteries."

Jay Lovestone realised that he would now be expelled from the American Communist Party. On 15th May, 1929 he sent a cable to Robert Minor and Jacob Stachel and asked them to take control over the party's property and other assets. However, as Theodore Draper has pointed out in American Communism and Soviet Russia (1960): "The Comintern beat him to the punch. On May 17, even before the Comintern's Address could reach the United States, the Political Secretariat in Moscow decided to remove Lovestone, Gitlow, and Wolfe from all their leading positions, to purge the Political Committee of all members who refused to submit to the Comintern's decisions, and to warn Lovestone that it would be a gross violation of Comintern discipline to attempt to leave Russia."

Foster, who had already gone on record as saying, "I am for the Comintern from start to finish. I want to work with the Comintern, and if the Comintern finds itself criss-cross with my opinions, there is only one thing to do and that is to change my opinions to fit the policy of the Comintern", now became the dominant figure in the party. Jay Lovestone, Benjamin Gitlow, Bertram Wolfe and Charles Zimmerman, now formed a new party the Communist Party (Majority Group).

By 1929 the American Communist Party only had 7,000 members. Most of these were immigrants living in and around New York City. There were also a large number involved in the arts including Elia Kazan, Erskine Caldwell, John Dos Passos, Howard Fast, Pete Seeger, Clifford Odets, Larry Parks, John Garfield, Howard Da Silva, Gale Sondergaard, Joseph Bromberg, Richard Wright, Dalton Trumbo, Richard Collins, Budd Schulberg, Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, Edwin Rolfe, Adrian Scott, Samuel Ornitz, Paul Jarrico, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., John Howard Lawson and Alvah Bessie.

The Great Depression helped the party grow and in the 1932 Presidential Election, the party candidate, Foster polled 102,991 votes (0.3), but Norman Thomas, the Socialist Party candidate, polled seven times that figure. Soon afterwards, Foster suffered a heart-attack and Earl Browder became the new leader of the American Communist Party. Foster moved to Moscow where he received treatment for his heart problems. He returned to the United States in 1935, but by this time Browder had established himself as the most important figure in the American Communist Party.

The leadership of the American Communist Party remained loyal to the foreign policy of the Soviet Union. It was argued that this was the best way to defeat fascism. However, this view took a terrible blow when on 28th August, 1939, Joseph Stalin signed a military alliance with Adolf Hitler. Browder and other leaders of the party decided to support the Nazi-Soviet Pact.

John Gates pointed out that this created serious problems for the party. "We turned on everyone who refused to go along with our new policy and who still considered Hitler the main foe. People whom we had revered only the day before, like Mrs. Roosevelt, we now reviled. This was one of the characteristics of Communists which people always found most difficult to swallow - that we could call them heroes one day and villains the next. Yet in all of this lay our one consistency; we supported Soviet policies whatever they might be; and this in turn explained so many of our inconsistencies. Immediately following the upheaval over the Soviet-German non-aggression pact came the Finnish war, which compounded all our difficulties since, here also, our position was uncritically in support of the Soviet action."

Earl Browder was the American Communist Party candidate in the 1940 Presidential Election, but the government imposed a court order forbidding him to travel within the country. His campaign efforts were limited to the issuing of written statement and the distribution of recorded speeches. In the election he won only 46,251 votes. Later that year he was found guilty of passport irregularities and sentenced to prison for four years. When the United States joined the Second World War and became allies with the Soviet Union, attitudes towards communism changed and Browder was released from prison after only serving 14 months of his sentence. Membership of the party also grew to 75,000.

In 1944 Earl Browder controversially announced that capitalism and communism could peacefully co-exist. As John Gates pointed out in his book, The Story of an American Communist (1959): "Browder had developed several bold ideas which were stimulated by the unprecedented situation, and now he proceeded to put them into effect. At a national convention in 1944, the Communist Party of the United States dissolved and reformed itself into the Communist Political Association." Ring Lardner, another party member, explained: "The change seemed only to bring the nomenclature in line with reality. Our political activities, by then, were virtually identical to those of our liberal friends."

Except for Foster and Benjamin Davis, the leaders of the American Communist Party unanimously supported Browder. However, in 1945, Jacques Duclos, a leading member of the French Communist Party and considered to be the main spokesman for Joseph Stalin, made a fierce attack on the ideas of Browder. As John Gates pointed out: " The leaders of the American Communists, who, except for Foster and one other, had unanimously supported Browder, now switched overnight, and, except for one or two with reservations, threw their support to Foster. An emergency convention in July, 1945, repudiated Browder's ideas, removed him from leadership and re-constituted the Communist Party in an atmosphere of hysteria and humiliating breast-beating unprecedented in communist history."

Foster now became the new chairman of the party. Two years later, after being criticised by leaders in the Soviet Union, Browder was expelled from the American Communist Party. He was later to argue: "The American Communists had thrived as champions of domestic reform. But when the Communists abandoned reforms and championed a Soviet Union openly contemptuous of America while predicting its quick collapse, the same party lost all its hard-won influence. It became merely a bad word in the American language."

On the morning of 20th July, 1948, Foster, and eleven other party leaders, included Eugene Dennis, Benjamin Davis, John Gates, Robert G. Thompson, Gus Hall, Benjamin Davis, Henry M. Winston and Gil Green were arrested and charged under the Alien Registration Act. This law, passed by Congress in 1940, made it illegal for anyone in the United States "to advocate, abet, or teach the desirability of overthrowing the government". The trial began on 17th January, 1949. As John Gates pointed out: "There were eleven defendants, the twelfth, Foster, having been severed from the case because of his serious, chronic heart ailment."

It was difficult for the prosecution to prove that the eleven men had broken the Alien Registration Act, as none of the defendants had ever openly called for violence or had been involved in accumulating weapons for a proposed revolution. The prosecution therefore relied on passages from the work of Karl Marx and other revolution figures from the past. When John Gates refused to answer a question implicating other people, he was sentenced by Judge Harold Medina to 30 days in jail. When Henry M. Winston and Gus Hall protested, they were also sent to prison.

After a nine month trial the leaders of the American Communist Party were found guilty of violating the Alien Registration Act and sentenced to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine. Robert G. Thompson, because of his war record, received only three years. They appealed to the Supreme Court but on 4th June, 1951, the judges ruled, 6-2, that the conviction was legal.

As John Gates pointed out in his book, The Story of an American Communist (1959): "To many in the leadership, this meant that the United States was unquestionably on the threshold of fascism. Had not Hitler's first step been to outlaw the Communist Party? We saw an almost exact parallel."

During the 20th Soviet Communist Party Congress in February, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He condemned the Great Purge and accused Joseph Stalin of abusing his power. He announced a change in policy and gave orders for the Soviet Union's political prisoners to be released. John Gates, the editor of The Daily Worker, became a supporter of Khrushchev and at his direction the newspaper printed the full text of Khrushchev's speech. This brought him into conflict with the leaders of the American Communist Party.

In April 1956 Eugene Dennis, published a report on the American Communist Party. As John Gates pointed out that it "was a devastating critique of the party's policies over a whole decade. Like all reports, it was not only his own, but had been discussed and approved by the National Committee members in advance. Dennis characterized the party's policies as super-leftist and sectarian, narrow-minded and inflexible, dogmatic and unrealistic." Foster, Benjamin Davis and Robert G. Thompson, constituted a minority of the leadership that led the attack on Dennis.

Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation policy encouraged people living in Eastern Europe to believe that he was willing to give them more independence from the Soviet Union. In Hungary the prime minister Imre Nagy removed state control of the mass media and encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. Nagy also released anti-communists from prison and talked about holding free elections and withdrawing Hungary from the Warsaw Pact. Khrushchev became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4th November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. During the Hungarian Uprising an estimated 20,000 people were killed. Nagy was arrested and replaced by the Soviet loyalist, Janos Kadar.

Some members of the American Communist Party were highly critical of the actions of Nikita Khrushchev and John Gates stated that "for the first time in all my years in the Party I felt ashamed of the name Communist". He then went on to add that "there was more liberty under Franco's fascism than there is in any communist country." As a result he was accused of being "right-winger, Social-Democrat, reformist, Browderite, peoples' capitalist, Trotskyist, Titoite, Stracheyite, revisionist, anti-Leninist, anti-party element, liquidationist, white chauvinist, national Communist, American exceptionalist, Lovestoneite, Bernsteinist".

Foster was a loyal supporter of the leadership of the Soviet Union and refused to condemn the regime's record on human rights. Foster failed to criticize the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Revolution. Large numbers left the party. At the end of the Second World War it had 75,000 members. By 1957 membership had dropped to 5,000.

On 22nd December, 1957, the American Communist Party Executive Committee decided to close down the Daily Worker. Gates argued: "Throughout the 34 years of its existence, the Daily Worker has withstood the attacks of Big Business, the McCarthyites and other reactionaries. It has taken a drive from within the party - conceived in blind factionalism and dogmatism - to do what our foes have never been able to accomplish. The party leadership must once and for all repudiate the Foster thesis, defend the paper and its political line, and seek to unite the entire party behind the paper."

Foster retired in 1957 and assumed the title of Chairman emeritus of the party. Gus Hall, also a loyal supporter of Stalinism, became the new leader of the party.

William Zebulon Foster died in Moscow on 1st September, 1961.

Primary Sources

(1) Theodore Draper, American Communism and Soviet Russia (1960)

Politics, work, adventure, were at this stage lumped together for Foster. He hoboed, but he was no ordinary hobo. He farmed, logged, mined, railroaded, but he was no ordinary farmer, logger, miner, or railroader. He went from radical organization to radical organization, but he was no ordinary radical. He was goaded on by an incessant drive to make something more of himself than an ignorant, down-trodden, submissive product of a Philadelphia slum. Politics interested him early. At fifteen, he says, he was stirred by William Jennings Bryan's campaign for the presidency in 1896. He came to the Socialist party in 1901. Eight years later, he was expelled as a member of a Left Wing faction in the state of Washington. By coincidence, it was the same year, 1909, that Charles Ruthenberg first joined the Socialist movement. The different paths they took at about the same time brought them to communism from different directions. Ruthenberg was able to go directly from Left Wing Socialism to Communism. Foster had to make a long detour to get to the same place.

For an American radical so "native" as Foster, European influences were destined to play a curiously crucial role. Trips to Europe determined the two turning points in his career.He was carried away the first time by what he heard and saw in France and Germany in 1910-11. In France, the anarcho-syndicalists controlled the official trade-union movement. In Germany, they were impotently aloof from the trade unions. To Foster, the lesson for the United States was clear: get into the official trade-union movement and "bore from within." This was his advice to the I.W.W., which he had joined after leaving the Socialists. He maintained that the I.W.W. was wrong to oppose the A.F. of L. with its own pure, revolutionary unions. It was better to go into the A.F. of L. and take it over. He returned home in the fall of 1911 to fight inside the I.W.W. for his great discovery. Though he failed to convince the great majority of syndicalists, he succeeded in winning over a small group of disciples.

Disappointed by the I.W.W. as he had been disillusioned by the Socialist party, Foster went into the business of radicalism for himself. He formed the Syndicalist League of North America in 1912. It lasted about two years. Then he formed the International Trade Union Educational League in 1915. It lasted about a year. These were small organizations on the fringe of the I.W.W., with which they mainly quarreled over trade-union tactics. While working as a car inspector in Chicago and as a member in good standing in the Railway Carmen's Union of the A.F. of L., Foster conceived of a more direct way to put his ideas into practice. He persuaded the A.F. of L. in 1917 to start an organizing campaign among the packing-house workers in the Chicago district. To his own surprise, he became secretary of the organizing committee, with John Fitzpatrick, president of the Chicago Federation of Labor, as chairman. Over 200,000 workers were soon enrolled.

(2) Theodore Draper, The Roots of American Communism (1957)

There was nothing Slavic about William Zebulon Foster. His father was an Irish immigrant; his mother came from English-Scotch stock. Born in Taunton, Massachusetts, near Boston, he spent his childhood in the slums of Philadelphia. His father washed carriages and plotted against the English. His mother produced twenty-three children, most of whom died in infancy, and devoted herself fervently to Catholicism. After quitting school at the age of ten, young Bill could not settle down to a place or a trade. For the next twenty-six years, he worked all over the country in a half-dozen industries - as logger, dock-worker, farm hand, trolley-car conductor, metal worker, seaman - rarely staying at one job or in one place for more than a few months. When nothing else turned up, he took to hoboing. He was a restless, self-educated, rebellious worker, a type that radicals dreamed about but rarely were.

(3) William Foster, Trade Unionism: The Road to Freedom (1921)

At heart and in their daily action the trade unions are revolutionary. Their unchangeable policy is to withhold from the exploiters all they have the power to. In these days, when they are weak in numbers and discipline, they have to content themselves with petty achievements. But they are constantly growing in strength and understanding, and the day will surely come when they will have the great masses of workers organized and instructed in their true interests. That hour will sound the death knell of capitalism. Then they will pit their enormous organization against the parasitic employing class, end the wages system forever and set up the long-hoped-for era of social justice. That is the true meaning of the trade union movement.

(4) William Foster, The Daily Worker (17th May, 1924)

Revolutions are not brought about by the type of far-sighted revolutionaries that you have in mind, but by stupid masses who are goaded to desperate revolt by the pressure of social conditions, and who are led by straight-thinking revolutionaries who are able to direct the storm intelligently against capitalism.

(5) William Foster, speech (8th October, 1925)

I am for the Comintern from start to finish. I want to work with the Comintern, and if the Comintern finds itself criss-cross with my opinions, there is only one thing to do and that is to change my opinions to fit the policy of the Comintern.

(6) William Foster, report (23rd August, 1928)

On the inner Party situation, he (Stalin) said he was opposed to our proposal for the removal of the Lovestone group from power at one blow, that this cannot be done from the top-meaning from here - leaving the implication that it must be done from below - at home. We very soon told him that we were not making such a proposal, but that our proposition was that the Communist International send an Open Letter to our Party criticizing the Right line of the Central Committee and the Lovestone group, and that a convention of the Party be held two months after the presidential elections. He stated that no good could come out of the Lovestone group, that they simply liked to play with policies and mass work. Although he did not commit himself to any particular program, we feel that in him we have a very good friend and supporter. We drew to his attention the fact that Bukharin had not criticized the Right-wing danger in the American Party and he said he would have to read the uncorrected stenogram of the Bukharin speech and that he would have a talk with him the following morning before going on his vacation for a month. We were very satisfied with the interview. How much he will actually intervene in our behalf here is an open question...Our conclusions from these meetings were about the following lines: That Stalin was decidedly against the Lovestone group and in favor of us, that he will have little influence in the present struggle now, but that the main support will come after we show him in the next few months that we are a fighting group and are fighting in the Party for our position.

(7) Los Angeles Illustrated Daily News (29th June, 1932)

William Z. Foster, Communist candidate for president, and nearly a score of persons seeking to hear him speak, were arrested yesterday by the police red squad as the leader attempted to address a political meeting at the Plaza. Of those seized, only Foster and three companions were held.

Foster was booked on suspicion of criminal syndicalism. With him were Edward W. Sandler, accused of disturbing the peace; Ezra F. Chase of the Sawtelle Soldiers' Home, and Raymond Lugo, 33, of the Midnight Mission, both booked on suspicion of criminal syndicalism.

Later in the day, Superior Judge Elliot Craig signed a writ of habeas corpus for Foster's release. Bond was fixed at $10,000 on the writ, which was made returnable today at 3:30 p.m.

Although Foster's sympathizers milled about the city for several hours, demonstrating against the arrested, violence was confined to the throwing of a few gas bombs by the police squad.

Local communist leaders had announced that they would hold a meeting at the Plaza in defiance of police orders, after a similar meeting in a hall on Broadway had been broken up by police. In addition to its political significance, the meeting was to protest the recent shooting of a member of the Unemployed Council in a police raid on an open meeting in a private home.

(8) C. H. Garrigues, Los Angeles Illustrated Daily News (30th June, 1932)

The politico-economic warfare which has engulfed the western world is already in America taking its final form — a battle to the death between communism and fascism, in the opinion of William Z. Foster, Communist candidate for president, who got out of jail early enough yesterday to give a brief interview before flying to Phoenix for a speaking engagement.

Neither socialism nor democracy, he declared, exists today as a living force; each constitutes only a moribund body of doctrine from which the rival forces are seeking to draw recruits. Each has lost, not numbers of lip-servers, but the once firm faith of its adherents that through one or the other doctrine lies salvation.

Socialism, he intimated, has been captured bodily by industrial leaders, now advancing theories half-socialist, half-fascist. Democracy is being attacked from without by communism, while its own leaders bore from within, seeking to undermine its walls and capture the citadel in the name of fascism.

The wave of contumely, contempt and ridicule directed at Congress during recent months is a deliberate attempt to destroy the confidence of the American people in representative government, clearing the way for a dictatorship, he says.

Even to one accustomed to finding the devil considerably less black than he is painted, the Communist leader proves a figure of disturbing contrasts. The blue eyes are mild, gentle, almost dreamy. He smiles quizzically as he talks, so that little laugh wrinkles appear about the corners. The lean, rugged fighter's jaw is in startling contrast.

One looks in vain for a sign of the zealot, the fanatic, the bigot. Foster, it seems, approaches the religion of communism not in the spirit of a missionary or a Savonarola, but as a priest celebrating its rites before the altar. When the time is ripe, the worshipers will come. Meanwhile, it is his duty to keep the font filled and the altar swept.

He disagrees with many non-Communists that the police departments' policy of suppression is helping the Communist cause. "It changes the direction; that's all," he says. "Makes the workers more determined; induces the fallen ones to answer force with force. But it doesn't help us, nor hurt us.

"Tear bombs can't unmake Communists because you can't fill a man's stomach with tear gas. Nor would it help the capitalists to let our leaders talk because campaign oratory can't fill a man's stomach either. The capitalists are damned if they do and damned if they don't. They know it and are afraid. That's why they hire policemen to beat us up."

(9) John Gates, The Story of an American Communist (1959)

One day I read a small item in the army daily newspaper Stars and Stripes . It reported that a New York newspaper had published a translation of an article in which Jacques Duclos, a top leader of the French Communist Party, severely criticized policies of the American Communists. The article, originally appearing in the French Communist theoretical magazine, ridiculed Browder's concept of the postwar world as utopian, condemned the dissolution of the Communist Party, and described Browder's ideas as a "notorious revisionism" of Marxism, than which there is no more serious criticism in the Communist dictionary.

These accusations infuriated me I immediately sent off a letter to Lillian in which I reaffirmed my belief in the come in letters from Lillian; she also sent me clippings of articles from the Communist press. The Duclos article had caused an upheaval in the American Communist movement. Excoriating Browder in the most extravagant terms, Duclos had praised the views of William Z. Foster, quoting from speeches and communications by Foster, of which the American Communists, except for the top leaders, had been entirely unaware.

Naturally, this created a sensation; the membership demanded to know why Foster's views had been kept secret from them. How Duclos found out about Foster's opinions I do not know, but clearly someone sent them to him. Foster's opposition to the Browder policies did not impress me. I wrote to Lillian that for years Foster had been the most sectarian and dogmatic of American Communist leaders; on the other hand, our most impressive gains had been made under the aegis of Browder.

Browder conceded that the Duclos article did not express the point of view of an individual French Communist, but was the considered opinion of the world's "most authoritative Marxists," meaning, of course, the Soviet Communists. The leaders of the American Communists, who, except for Foster and one other, had unanimously supported Browder, now switched overnight, and, except for one or two with reservations, threw their support to Foster. An emergency convention in July, 1945, repudiated Browder's ideas, removed him from leadership and re-constituted the Communist Party in an atmosphere of hysteria and humiliating breast-beating unprecedented in communist history.

Browder's view of the postwar world was undoubtedly over-optimistic. He underestimated the clash that would develop among the allies once the war was over. But he was not the only leader to make such a mistake; it was made by the leaders of every other political trend as well.

Browder did have a vision-that World War II would usher in a new kind of world where war would be unthinkable and where the communist and capitalist worlds would have to compete and collaborate. Perhaps he did not foresee the difficulties that would lie in the path and the hard struggles that would be needed to bring this about, but his prescience was sound in many major respects.

Probably his greatest contribution was his effort to adapt the Communist Party to the American scene. Toward that end he demonstrated more creativity and greater imagination, independence and originality of thought than anyone before or since.

Only a few years later I was to learn from someone who spoke with Duclos in 1946 that the world communist movement did not consider Browder's most serious error his myopic view of the postwar era (they had all made similar estimates), but rather his dissolution of the Communist Party. Here was the unforgivable heresy. Browder had violated the one thing so sacred that no one could dare tamper with it: the concept of the Communist Party as it had been laid down by Lenin in 1902.

In 1946 Browder was expelled from the American Communist Party for refusing to accept the new policy and for publishing a bulletin not authorized by the party (and because Foster was determined to be rid of him). For several years Browder protested that his ideas were closer to the Soviet view than were the American party's.

(10) John Gates, The Story of an American Communist (1959)

The main report by Eugene Dennis (in April 1956) was a devastating critique of the party's policies over a whole decade. Like all reports, it was not only his own, but had been discussed and approved by the National Committee members in advance. Dennis characterized the party's policies as super-leftist and sectarian, narrow-minded and inflexible, dogmatic and unrealistic.

He singled out the crucial issue of the "war danger," and in effect, admitted that much of what the party had done since Browder's time had been based on a misreading of world and domestic realities. Though Foster's name was not mentioned, and the entire leadership was indicted, the inference was unmistakable. Dennis projected the idea of replacing the party with a "united, mass party of Socialism," whose doctrinal basis would necessarily have to be much broader than our own, and which was to be formed with many Socialist-minded Americans outside our own ranks.

Dennis carefully, and characteristically, avoided putting his finger on the basic reason for the party's failures, namely, our worshipful and imitative relationship to the Soviet Union. On the other hand, Max Weiss, the national educational director at that time, who had never been accused of undogmatic tendencies, gave the report on the XX Congress and he unmistakably concluded that our relations with the Soviet Communists had been wrong, unequal, one-sided, and harmful.

William Z. Foster was present at this decisive meeting and he vehemently opposed the reports of Dennis and Weiss. In his view, the party had been guided as well as possible, and history would vindicate his leadership. Foster was a remarkable man, a workingman who had educated himself. He had been one of America's finest labor organizers. Samuel Gompers, John L. Lewis, and Philip Murray had all paid him this tribute...

Foster stood alone at this meeting, except for the half-hearted support of Benjamin J. Davis, the former New York councilman, who had been (with Thompson) one of the architects of the Party's debacle; Davis was the man who had said at an open-air meeting in 1949 that he "would rather be a lamppost in Moscow than president of the United States." Foster voted against the Dennis report and Davis abstained.

My own remarks at this meeting were different than any speech I had previously made. I felt it was time for the party to know of the profound differences in the leadership that had prevailed for a decade. Obviously, the Foster view was in irreconcilable opposition to the majority: it was time to let the membership know the facts honestly. Others spoke in a similar vein. Yet the opportunity was missed, and once again the facts were concealed from the membership. No doubt, this contributed greatly to the loss of confidence in the ranks, which almost immediately afterward began to thin out.

At this same meeting, I had a curious but revealing exchange with Foster. I had spoken of his many monumental works that had been eulogized by party leaders, but none of us had bothered to find why so few Americans read these books, and why they had so little influence; too often, they had simply been dumped on the lower party organizations, but were not read or sold. Someone chided me for being rude to so old a man, with so venerable a record. I went over and said I hoped he realized there was nothing personal in this criticism. To which he replied, most genially, that he was not the least bothered by it. "Why," he exclaimed. "My books have been translated all over the world . . . into Russian, into Chinese, and many other languages." I was struck by Foster's complete divorce from interest in America. It did not seem to matter that few Americans were influenced by his work, so long as foreign Communists held him in high repute, or so he believed. He saw himself a world figure. He lived in a make-believe world of his own, and though more typically "American" than most party leaders, he was also strangely remote from his own land and people.

(11) John Gates, The Story of an American Communist (1959)

Inevitably I became deeply involved in the inner politics of the party's highest committee. Browder had been expelled and his ideas defeated; Foster had emerged the party's outstanding leader, the only one in fact unblemished by the Browder heresy. But within the leadership itself the struggle went on as two groupings developed, one around Foster, the party chairman, and the other around Eugene Dennis, who became in 1946 general secretary.

Supporting Foster were only Robert Thompson and Benjamin J. Davis, Jr., the former being the youngest member of the leadership, three years younger than myself. A hero of World War II, winner of the Distinguished Service Cross, a battalion commander in Spain where he had been wounded in action, Thompson was courageous and able in military matters. In politics he was a novice who seemed unable to grasp the fact that the military approach is wholly inadequate in politics and human relations.

In the upheaval accompanying Browder's ouster, Thompson became the head of the important New York organization, comprising half the total national membership of the party. Here he replaced Gil Green, probably the most able of all the party leaders at the time, who relinquished his post because he felt personally guilty for past party policy as one of the most prominent Browderites. Green now went back to Chicago, where he had been born and where he hoped to redeem himself. When Thompson was given the New York leadership, he was politically an unknown quantity, promoted on the basis of his wartime reputation. Benjamin J. Davis, Jr. was the son of a Republican national committeeman from Atlanta, Georgia, and a graduate of Amherst and Harvard Law School. He came into prominence as an attorney in the Angelo Herndon case during the course of which he joined the Communist Party. Coming to New York, he joined the staff of the Daily Worker, and along with Brooklyn Communist Peter V. Cacchione, was elected to the City Council of New York when the system of proportional representation was in effect. A big, powerful man with a passion for oratory, he has been the most prominent Negro Communist since James W. Ford.

Foster, Thompson and Davis constituted a minority of the leadership and were ranged against a majority centering around Dennis. Ineffectual in many ways, almost painfully shy, a poor speaker, Dennis nevertheless was an astute politician. He was experienced in American politics and adept at getting things done behind the scenes, a skilled wire-puller and manipulator. His impressive exterior belied his introverted personality, for he was tall, ruddy, robust, with a mop of grey hair; a handsome and striking-looking Irishman. Despite his inadequacies as a public leader, Dennis resisted Foster's policies at this time and was our best symbol.

The Foster group pressed for super-militant policies which in Communist terminology we called "left-sectarian" because they isolated us from the people. Our group stood for broader, more flexible policies which our opponents, again in Communist parlance, called "right opportunism," which meant sacrificing principle for the sake of mass popularity.