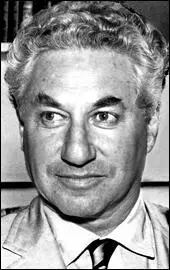

Budd Schulberg

Budd Schulberg, the son of the Hollywood movie producer, Benjamin Schulberg, was born in New York on 27th March, 1914. His father was a former screenwriter who had risen to head of production at Paramount Studios. His mother, Adeline Schulberg, was a literary agent who had been an active member of the suffrage movement.

In his autobiography, Moving Pictures: Memories of a Hollywood Prince (1981): "For, by the time I appeared in 1914, my father was working for one of the first film tycoons, the diminutive, untiring immigrant fur worker, Adolph Zukor, whose Famous Players Company was still a fledgling. For writing scenarios and publicity, (my father) had now achieved the lordly salary of fifty dollars a week. And he was moonlighting: writing a series of four one-reel documentaries on Sylvia Pankhurst, the English suffragist leader, who had come to America to promote the cause, and who had been dragged off to jail from the meeting my mother had attended. It was through Adeline's connections with the movement that my father had gotten the assignment, at fifty dollars per reel. So my birth had been financed in true collaboration: my father's screenwriting skills married to my mother's interest in the feminist pioneers. This was a first for all three of us: my first moments on earth, my father's first documentary film, and my mother's first efforts as a writer's agent.".

In 1931 Schulberg was sent to Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts. This was followed by Dartmouth College, New Hampshire. "In high spirits, I went up to Dartmouth... For me, the Dartmouth campus was love at first sight: the old New England village we drove through to reach the campus; the row of white 18th-century buildings; the inviting look of Baker Library; the coziness of its Tower Room; the sound of the chimes; the White Mountains in the background; the wide Connecticut River separating the college from the rolling green hills rising to the Green Mountains of Vermont; the impressive daily newspaper I longed to work on. The look of the student body appealed to me, checked wool shirts and windbreakers, a rugged up-country look that fulfilled our image of Dartmouth as northern New England's answer to the effeteness of Harvard or the southern-gentleman tradition of Princeton."

Schulberg held left-wing views and in 1934 he visited the Soviet Union where he heard Maxim Gorky make a speech on socialist realism at the first Soviet Writers' Congress. He was also impressed by the work of Vsevolod Meyerhold. In 1936 Schulberg graduated from Dartmouth College. After returning to Hollywood he joined the Communist Party (1937-40). However, these views were not evident in his first two screenplays, Little Orphan Annie (1938) and White Carnival (1939). He also married Virginia Ray, a fellow member of the Communist Party.

Schulberg lost his job with Paramount Studios after the failure of White Carnival and he turned to writing novels. His first novel, a satire of Hollywood power and corruption, brought him into conflict with his father, Benjamin Schulberg, who feared the book would create an anti-semitic backlash. John Howard Lawson and Richard Collins of the Communist Party also suggested a more positive portrait of a strike led by the Screen Writers Guild. Schulberg refused and in 1940 left the party. What Makes Sammy Run? was published in 1941.

After divorcing his first wife in 1942, Budd Schulberg enlisted in the US Navy. He was assigned to a documentary film unit run by John Ford. In 1945 he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant and later that year he was assigned to gather photographic evidence to be used at the Nuremberg War Crimes trials.

On his return to the United States, Schulberg, began work on a novel about boxing, The Harder They Fall (1947). The book was based on the career of Primo Carnera and his fights with Jack Sharkey, Paulino Uzcudun, Tommy Loughran and Max Baer.

In 1947 the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) opened its hearings concerning communist infiltration of the motion picture industry. The chief investigator for the committee was Robert E. Stripling. The first people it interviewed included Ronald Reagan, Gary Cooper, Ayn Rand, Jack L. Warner, Robert Taylor, Adolphe Menjou, Robert Montgomery, Walt Disney, Thomas Leo McCarey and George L. Murphy. These people named several possible members of the American Communist Party.

As a result their investigations, the HUAC announced it wished to interview nineteen members of the film industry that they believed might be members of the American Communist Party. This included Larry Parks, Herbert Biberman, Alvah Bessie, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Dalton Trumbo, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., Samuel Ornitz, John Howard Lawson, Waldo Salt, Bertolt Brecht, Richard Collins, Gordon Kahn, Robert Rossen, Lewis Milestone and Irving Pichel.

The first ten witnesses called to appear before the HUAC, Biberman, Bessie, Cole, Maltz, Scott, Trumbo, Dmytryk, Lardner, Ornitz and Lawson, refused to cooperate at the September hearings and were charged with "contempt of Congress". Known as the Hollywood Ten, they claimed that the 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to do this. The courts disagreed and each was sentenced to between six and twelve months in prison. The case went before the Supreme Court in April 1950, but with only Justices Hugo Black and William Douglas dissenting, the sentences were confirmed.

Richard Collins gave evidence on 12th April, 1951. He told the HUAC that he had been recruited to the American Communist Party by Budd Schulberg in 1936. He named John Howard Lawson as a leader of the party in Hollywood. Collins also claimed that fellow members of his communist cell included Ring Lardner Jr. and Martin Berkeley. He also named John Bright, Lester Cole, Paul Jarrico, Gordon Kahn, Albert Maltz, Samuel Ornitz, Robert Rossen, Waldo Salt and Frank Tuttle. Collins estimated that the Communist Party in Hollywood during the Second World War had several hundred members and he had known about twenty of them.

When Schulberg heard the news he sent a telegram to the HUAC offering to provide evidence against former members of the American Communist Party. On 23rd May, 1951 Schulberg agreed to answer questions and admitted he joined the party in 1937. He also stated that Herbert Biberman, John Bright, Lester Cole, Richard Collins, Paul Jarrico, Gordon Kahn, Ring Lardner Jr., John Howard Lawson and Waldo Salt had all been members. He also explained how party members such as Lawson and Collins had attempted to influence the content of his novel, What Makes Sammy Run?

Schulberg left the party in 1940 because of a dispute with Victor Jeremy Jerome: "It was suggested that I talk with a man by the name of V. J. Jerome, who was in Hollywood at that time. I went to see him... I didn't do much talking. I listened to V. J. Jerome. I am not sure what his position was, but I remember being told that my entire attitude was wrong; that I was wrong about writing; wrong about this book, wrong about the party; wrong about the so-called peace movement at that particular time; and I gathered from the conversation in no uncertain terms that I was wrong. I don't remember saying much. I remember it more as a kind of harangue. When I came away I felt maybe, almost for the first time, that this was to me the real face of the party. I didn't feel I had talked to just a comrade. I felt I had talked to someone rigid and dictatorial who was trying to tell me how to live my life, and as far as I remember, I didn't want to have anything more to do with them."

After giving evidence to the House of Un-American Activities Committee Schulberg was free to return to Hollywood scriptwriting. He worked with Elia Kazan, another former Communist Party member who named names, on the Academy Award winning film, On the Waterfront (1954). Schulberg won one of the film's eight oscars. A collection of short stories, Some Faces in the Crowd, was published in 1954. Other films that he wrote the screenplay for included The Harder They Fall (1956) and A Face in the Crowd (1957).

Schulberg retained his liberal views and founded the Watts Writers Workshop in 1964 and the Frederick Douglass Creative Arts Centre in New York City in 1971. He later received the Amistad award for his work with African-American writers. His autobiography, Moving Pictures: Memories of a Hollywood Prince was published in 1981.

Budd Schulberg, who was married four times and had fathered five children, died on 5th August 2009.

Primary Sources

(1) Budd Schulberg, Moving Pictures: Memories of a Hollywood Prince (1981)

For, by the time I appeared in 1914, my father was working for one of the first film tycoons, the diminutive, untiring immigrant fur worker, Adolph Zukor, whose Famous Players Company was still a fledgling. For writing scenarios and publicity, (my father) had now achieved the lordly salary of fifty dollars a week. And he was moonlighting: writing a series of four one-reel documentaries on Sylvia Pankhurst, the English suffragist leader, who had come to America to promote the cause, and who had been dragged off to jail from the meeting my mother had attended. It was through Adeline's connections with the movement that my father had gotten the assignment, at fifty dollars per reel. So my birth had been financed in true collaboration: my father's screenwriting skills married to my mother's interest in the feminist pioneers. This was a first for all three of us: my first moments on earth, my father's first documentary film, and my mother's first efforts as a writer's agent.

My delivery, my baby clothes, and all the luxuries that would be lavished on my infancy were supplied by the latest and liveliest of the arts. My first carriage was presented to me by the Adolph Zukors, and from their farm outside the city they sent fresh milk and eggs to help little Buddy, as I was called, grow strong. The Zukors' son-in-law, Al Kaufman, an executive in the young company and a crony of B.P.'s, presented me with a sailor suit. Mary Pickford, at twenty-one the most famous of the Famous Players, sent Buddy a woolly blanket. B. P. had just written one of her current movies (and long one of her favorites), Tess of the Storm Country, and had coined the phrase that practically became part of her name, "America's Sweetheart." The business that people had scoffed at as an overnight fad when my father first drifted into it was going through its first great transition. Mary Pickford (nee Gladys Smith), who had earned five dollars a day as an anonymous extra in 1909, was earning an astronomical four thousand dollars a week in 1914. The American public, tired of stale vaudeville jokes and third-rate touring companies, had discovered its favorite form of entertainment. Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin and Theda Bara, the Keystone Kops and the Bathing Beauties were the angels flying round my crib.

(2) Budd Schulberg, Moving Pictures: Memories of a Hollywood Prince (1981)

In high spirits, I went up to Dartmouth. There was a small but enthusiastic group of us, including our Deerfield version of Superman, Mutt Ray. For me, the Dartmouth campus was love at first sight: the old New England village we drove through to reach the campus; the row of white 18th-century buildings; the inviting look of Baker Library; the coziness of its Tower Room; the sound of the chimes; the White Mountains in the background; the wide Connecticut River separating the college from the rolling green hills rising to the Green Mountains of Vermont; the impressive daily newspaper I longed to work on. The look of the student body appealed to me, checked wool shirts and windbreakers, a rugged up-country look that fulfilled our image of Dartmouth as northern New England's answer to the effeteness of Harvard or the southern-gentleman tradition of Princeton. Mutt Ray seemed perfect Dartmouth material, and I felt a little more rugged myself as I walked at his side, inspecting the sentimental landmarks, the old covered bridge and the 18th-century Daniel Webster Cottage, where perhaps the most eloquent of all New Hampshiremen had lived as an undergraduate, years before he became a senator, a presidential hopeful, a secretary of state, and the successful defender of the college in the crucial Dartmouth College Case. Every freshman memorizes Webster's summation: "Dartmouth, sirs,'tis a small college, but there are those of us who love it."

To climax our day, Rudy Pacht, now established as one of the stalwarts of the freshman football team, introduced us to Bill Morton, Dartmouth's reigning backfield star, and one of her all-time greats. After being in his presence, I found my interview with Dean Bill a decided anticlimax.

(3) Budd Schulberg, Moving Pictures: Memories of a Hollywood Prince (1981)

But what did I have to write about? All I knew about was growing up in Hollywood. And even though I had made some notes on Von Stroheim and Von Sternberg, on Eisenstein and Clara Bow, I knew I wasn't ready. What made me choose the subject I did remains one of those social mysteries. All I remember is that it was triggered by a book I happened to read, recommended by one of the writers who came to our house, the hard-drinking rebel Jim Tully, who liked to grouse to Mother about the honest books Hollywood was afraid to make into films. One of these was The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man by James Weldon Johnson.

It did what good books are supposed to do. I could not put it out of my mind. It made me want to write a book of my own. It is about a light-skinned "colored man," a classical musician, a cultural aristocrat traveling in the South who follows a crowd to a lynching he is only able to watch because the redneck posse takes him for white. Johnson describes the victim dragged in between two horsemen, his eyes glazed with fear and pain, already more dead than alive. No mention is made of his crime; in this atmosphere of mindless violence, it doesn't really matter....

While the author looks on in numb horror, the limp black body is chained to the post, drenched with gasoline, and set on fire. Cheers and sadistic laughter mingle with the screams and groans of the dying man. Johnson looks around at the fiends who accept his terrified passivity for compliance, and there and then decides on a coward's escape. He will cease to be a black man. It is too dangerous and too degrading. He will go north and pass as a member of the ruling majority. This he does successfully until he falls in love with a beautiful white girl attracted to him by his sensitivity and his classical musicianship. He feels he cannot marry her without revealing his racial secret. When he does, she leaves him, bereft. Eventually they are reunited, and he lives a life of white respectability. But in the end, seeing "a small but gallant band of colored men publicly fighting for their race," he is made to feel small, weak, selfish, and empty. He has, in the final line of the book, which went into my diary and indelibly into my impressionable young mind, "sold his birthright for a mess of pottage."

The closest I had ever been to a lynching was the playful if sometimes spiteful goosing of Oscar the Bootblack at Paramount Studio. And Oscar would not scream in pain but in feigned, obsequious delight. But as I read the nightmare episode in the Johnson autobiography, I pictured Oscar chained to a stake and writhing in agony as the fire devoured his flesh. And I decided to try writing a story about it. Aware that I lacked the details of a firsthand observer, I chose to tell it through the eyes of a child carried on the shoulders of his father and not really comprehending what he is seeing. When the Stockade rejected it as unfit material for our precious magazine, I sent it to Mrs. Stanton, who thought it quite well done but of course in need of rewriting. With this meager encouragement, I decided on a bolder course. I would write a book about lynching, and about the persecution of the Negroes in the South. With the courage of my ignorance and the benign arrogance of youth, I wrote to Clarence Darrow. I had not yet read any of his books, but I had heard of him through my parents as a fighter for the right and a defender of underdogs.

Whatever private doubts Clarence Darrow may have had about the abilities of a prep-school teenager to write a book on lynching and the virulence of white supremacy, he answered promptly in his own handwriting: "You can get all the information there is by writing Mr. Walter White, 69 Fifth Avenue, New York City. Sec., National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. (NAACP) I am glad you are doing this work. More power to you."

A letter to Walter White also brought a quick response. One pamphlet enlightened me as to the makeup of the NAACP My James Weldon Johnson was a vice-president, W. E. B. DuBois edited the Crisis, its principal publication, and Roy Wilkins assisted Mr. White. Another pamphlet listed the recorded lynchings over the past forty years. Averaging as many as one a week, in the first six months of 1931 there had been twenty-nine. Although rape of white women was the accepted justification, fewer than 25 percent had interracial sexual implications. "Rape," according to eyewitness reports, could be anything from a familiar greeting to a questionable glance. Negroes had been lynched for arguing with white landowners over their share of the crops, for daring to strike back at their tormentors, or simply for being "uppity."

The statistics shook the mind, but the case histories told in down-home language by the families of victims stabbed the heart. Klansmen and night raiders had gone out on "N***** hunts," torturing their victims before burning them or tying ropes to their necks and throwing them over the sides of bridges. A 12-year-old had been hacked to death because a white woman had complained that he had talked to her "disrespectfully." The few whites who dared stand up to the fury of the mob were treated with equal brutality. The NAACP believed in fighting for justice in the courts, inside the system. But the lawyers they sent down to defend the victims of legal lynching - the thousands of blacks railroaded to Death Row and to chain gangs for life without even the trappings of a fair trial-were themselves threatened by lynch mobs not in the hate-ridden hamlets of Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi, but even in the courtrooms themselves. Redneck judges openly sympathized with the white prosecutors, while the white audience booed and hissed the northern lawyers as if they were attending a 50-cent melodrama.

Most of these lawyers, it seemed to me, were from New York and had Jewish names. As I read the press accounts of their attempts to speak out for their illiterate and terrified clients, I tried to put myself in their place. After all, if I were going to write my book on lynching, the first of its kind - for amazingly I could find no single volume devoted entirely to this grisly subject - I really should attend one of those trials, and get the smell and feel of the subhuman mobs who terrorized the rural South and made a mockery of the Emancipation Proclamation and the 14th, 15th, and 16th Amendments.

(4) Budd Schulberg, Moving Pictures: Memories of a Hollywood Prince (1981)

Until I happened upon that lynch scene in the Johnson book and then reinforced it by reams of material on this year's atrocities, I had not imagined that the practice was just as prevalent in the early 1930s as it had been in the late 1860s. Lynch "law," I discovered, was simply a way of circumventing the abolitionist victory in the Civil War. And if the Negro dared complain about his condition, he was marked as a "bad N******," inviting the treatment that had terrified James Weldon Johnson into going north and passing for white.

The NAACP reports made it clear that the fifty-odd lynchings every year were only the bloody tip of a gruesome iceberg, for local sheriffs in league with the night riders were not disposed to cite the lynchings to higher authorities. And the families of the black victims were almost always terrified into silence for fear of receiving the same treatment.

But, I learned from this extracurricular reading, a new case was scandalizing the Negro, liberal/ radical, and literary communities, and the European intelligentsia, even though it had been largely ignored in our regular press. The latest victims were called the Scottsboro Boys, and although I had never heard of them until that fall, they were to become a cause celebre of the Thirties as polarizing as Sacco-Vanzetti in the Twenties. Indeed, many of the writers speaking out in support of the nine teenage Scottsboro prisoners had also protested the execution of the two Italian immigrants. I recognized Heywood Broun, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Theodore Dreiser, Lincoln Steffens, Dorothy Parker, Sherwood Anderson, Sinclair Lewis.... To Mother's and Father's credit I was already aware of all these writers, and had met at least half of them.

I sent for everything available on the Scottsboro Boys. They were nine black back-country youths aged thirteen to nineteen, jobless and destitute, who rode a freight car in search of work in a larger town. A fistfight between them and young white hoboes who objected to sharing the boxcar had resulted in one of the white boys either jumping off or being thrown off the train and phoning the local police. When the nine "Scottsboro Boys" were taken off the train and arrested at the next stop, it was revealed that two of the "white boys" were girls dressed in baggy overalls like their fellow rod-riders.

Apparently this was all the evidence necessary to build a case that the nine black boys had raped the two white girls. The black youths had tried to explain that they did not even know the girls had been masquerading as boys. Accused of rape, the nine boys were rushed to trial in the usually sleepy Alabama hamlet of Scottsboro, while a mob of ten thousand outraged rednecks shouted for their blood. In three days they were convicted by an all-white jury and sentenced to death. Even when one of the girls-both of them had police records for prostitution wrote a letter to a boyfriend: "Those policemen made me tell a lie ... those Negroes did not touch me ... I wish those Negroes are not burnt on account of me ...," the death sentence stood.

(5) Budd Schulberg, telegram to House of Un-American Activities Committee (12th April, 1951)

I have noted the public statement of your committee inviting those named in recent testimony to appear before your committee. My recollection of my communist affiliation is that it was approximately from 1937 to 1940. My opposition to communists and Soviet dictatorship is a matter of record. I will co-operate with you in any way I can.

(6) In his testimony before the House of Un-American Activities Committee Budd Schulberg claimed that the Communist Party had tried to influence the content of his novel, What Makes Sammy Run? (April, 1951)

The feeling was that it was too individualistic; that it didn't begin to show what were called the progressive forces in Hollywood; and that it was something they thought should be either abandoned or discussed with some higher authority before I began to work on it.

Richard Collins and John Howard Lawson suggested I submit an outline and discuss the whole matter further. I decided I would have to get away from this if I was ever to be a writer. I decided to leave the group, cut myself off, pay no more dues, listen to no more advice, indulge in no more literary discussions, and to go away from the Party, from Hollywood, and try to write a book, which is what I did.

(7) Budd Schulberg, House of Un-American Activities Committee (23rd May, 1951)

It was suggested that I talk with a man by the name of V. J. Jerome, who was in Hollywood at that time.

I went to see him. Looking back, it may be hard to understand why, after all these wrangles and arguments, I should go ahead and see V. J. Jerome. But maybe every writer has an insatiable curiosity about these things; I don't know.

Anyway, I went. It was on Hollywood Boulevard in an apartment. I didn't do much talking. I listened to V. J. Jerome. I am not sure what his position was, but I remember being told that my entire attitude was wrong; that I was wrong about writing; wrong about this book, wrong about the party; wrong about the so-called peace movement at that particular time; and I gathered from the conversation in no uncertain terms that I was wrong.

I don't remember saying much. I remember it more as a kind of harangue. When I came away I felt maybe, almost for the first time, that this was to me the real face of the party. I didn't feel I had talked to just a comrade. I felt I had talked to someone rigid and dictatorial who was trying to tell me how to live my life, and as far as I remember, I didn't want to have anything more to do with them.

(8) Budd Schulberg was interviewed by Victor Navasky when he was writing his book, Naming Names (1982)

These people (those he named), if they had it in them, could have written books and plays. There was not a blacklist in publishing. There was not a blacklist in the theatre. They could have written about the forces that drove them into the Communist Party. They were practically nothing written. Nor have I seen these people interested in social problems in the decades since. They're interested in their own problems and in the protection of the Party.

(9) Tim Weiner, New York Times (5th August, 2009)

The son of a movie mogul, Mr. Schulberg was twice ostracized by Hollywood and twice fought back with his typewriter. The first time came in 1941, with his first novel, “What Makes Sammy Run?,” a depiction of back-lot back stabbing. The story’s antihero, Sammy Glick, a product of the Lower East Side, is a young man on the make who will lie, cheat and steal to achieve success, rising from newspaper copy boy to Hollywood boss on the strength of his cutthroat ambition. “The spirit of Horatio Alger gone mad,” Mr. Schulberg said.

The book cut so close to the bone that Mr. Schulberg was warned that he would never work in the film industry again.

The second time Mr. Schulberg faced professional ruin was when he appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1951 during its relentless investigation of the Communist Party’s influence on the movie industry.

Mr. Schulberg had gone to the Soviet Union in 1934 and joined the Communist Party of the United States after he returned to Hollywood. “It didn’t take a genius to tell you that something was vitally wrong with the country,” he said in the 2006 interview, recalling his decision to join the party.

“The unemployment was all around us,” he said. “The bread lines and the apple sellers. I couldn’t help comparing that with my own family’s status, with my father; at one point he was making $11,000 a week. And I felt a shameful contrast between the haves and the have-nots very early.”

His romance with Communism ended six years later, when he quit the party after feeling pressure to bend his writing to fit its doctrines.

Mr. Schulberg had been identified as a party member in testimony before the House committee. Called to testify, he publicly named eight other Hollywood figures as members, including the screenwriter Ring Lardner Jr. and the director Herbert Biberman.

They were two among the Hollywood 10 — witnesses who said the First Amendment gave them the right to think as they pleased and keep their silence before the committee. All were blacklisted and convicted of contempt of Congress. Losing their livelihoods, Lardner served a year in prison and Biberman six months.

In the turmoil of the Red Scare, Mr. Schulberg’s testimony was seen as a betrayal by many, an act of principle by others. The liberal consensus in Hollywood was that Lardner had acquitted himself more gracefully before the committee when asked if he had been a Communist: “I could answer it, but if I did, I would hate myself in the morning.”

In the 2006 interview, Mr. Schulberg said that in hindsight he believed that the attacks against real and imagined Communists in the United States were a greater threat to the country than the Communist Party itself. But he said he had named names because the party represented a real threat to freedom of speech.

“They say that you testified against your friends, but once they supported the party against me, even though I did have some personal attachments, they were really no longer my friends,” he said. “And I felt that if they cared about real freedom of speech, they should have stood up for me when I was fighting the party.”

(10) The Daily Telegraph (5th August, 2009)

Budd Wilson Schulberg was born in New York on March 27 1914. His Jewish forebears had fled the Russian pogroms in the 19th century, but by the time of Budd's birth his parents were comfortably-off middle-class New Yorkers. His father was just getting started in the infant film business, while his mother drilled into her son the wisdom of education and self-improvement. Budd said later: "She was determined I was going to be a combination of Stephen Crane and John Galsworthy."

When Budd was five the family moved to Hollywood, where his father became a producer. An observant child, Budd knew by the time he was in Los Angeles High School that film-making could be anything but glamorous, with its background of feuds and backbiting, and the drudgery of scenes shot over and over again by "temperamental directors overborne by demoniac producers and conniving stars".

He later observed: "For the most part the industry looked like an overpowering giant who, when he opens his mouth, talks baby talk." He was particularly appalled by the lives of child stars, whom he called victims of child labour. In their teens, he said, most of them rebelled, turning to drink and drugs, unloving sex and careless marriages.

While all this was his kindergarten, Schulberg said, the city also offered an advanced course in psychodrama, neurasthenia and pathological insecurity. "The star system," he wrote, "demanded intelligence and/or strength of character to cope with the pressures of excessive celebrity, but they came up too fast to learn along the way. They floundered and fluttered like wounded birds in the blinding and confusing light of their stardom."

(11) Dennis McLellan, The Los Angeles Times (6th August, 2009)

The son of B.P. Schulberg, the powerful production chief of Paramount Pictures in the 1920s and early '30s, Budd Schulberg burst onto the literary scene in 1941 at 27 with his first novel, "What Makes Sammy Run?"

A vivid portrait of a brash and amoral young hustler from New York's Lower East Side who connives his way from newspaper copy boy to Hollywood producer, the novel is considered one of the best about Hollywood, and the name of Schulberg's back-stabbing anti-hero, Sammy Glick, has become synonymous with ruthless ambition.

Viewed as a savage indictment of the movie business, the novel drew the immediate ire of the Hollywood establishment. As Schulberg once put it: "Overnight, I found myself famous -- and hated."

Movie columnist Hedda Hopper, encountering Schulberg in a Hollywood restaurant, huffed, "How dare you?"

A furious Samuel Goldwyn, for whom Schulberg was then working as a screenwriter, fired him because of "that horrible book."

MGM studio chief Louis B. Mayer not only denounced the book at a meeting of the Motion Picture Producers Assn. but also suggested that Schulberg be deported. To which B.P. Schulberg laughed and said, "Louie, he's the only novelist who ever came from Hollywood. Where the hell are you going to deport him, Catalina Island?"