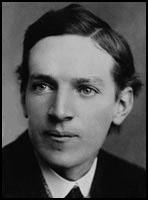

Upton Sinclair

Upton Sinclair was born in Baltimore on 20th September, 1878. His alcoholic father moved the family to New York City in 1888. Although his own family were extremely poor, he spent periods of time living with his wealthy grandparents. He later argued that witnessing these extremes turned him into a socialist.

A religious boy with a great love of literature, his two great heroes were Jesus Christ and Percy Bysshe Shelley. An intelligent boy he did well at school and at 14 entered New York City College. Soon afterwards he had his first story published in a national magazine.

Over the next few years Sinclair funded his college education by writing stories for newspapers and magazines. By the age of 17 Sinclair was earning enough money to enable him to move into his own apartment while supplying his parents with a regular income. In January 1901 he borrowed $200 from his uncle and printed a thousand copies of Springtime and Harvest. Following two newspaper articles he managed to sell enough copies to repay the loan.

Socialism

In October 1902 Sinclair met the writer Leonard Dalton Abbott. He introduced him to George Davis Herron, a founder of the Rand School of Social Science, and Gaylord Wilshire. All the men were members of the Socialist Party of America, and suggested that he should read the books of Karl Marx, Peter Kropotkin, Edward Bellamy, Karl Kautsky, Frank Norris, Jack London, Robert Blatchford and Thorstein Veblen. Sinclair took their advice and he soon became a committed socialist.

Sinclair married Meta Fuller in 1902. He continued to publish novels. This included The Journal of Arthur Stirling (1903), Prince Hagen (1903) and Manassas: A Novel of the Civil War (1904), but they all sold badly. However, he had began to get favourable comments from critics.

The work of Frank Norris was especially important to the development of Sinclair as a writer. He later spoke about how Norris had "showed me a new world, and he also showed me that it could be put in a novel." Sinclair was also influenced by the investigative journalism of Benjamin Flower, Ida Tarbell, Lincoln Steffens and Ray Stannard Baker. Sinclair argued: "The proletarian writer is a writer with a purpose; he thinks no more of art for art's sake than a man on a sinking ship thinks of painting a beautiful picture in the cabin; he thinks of getting ashore - and then there will be time enough for art."

The Jungle

In 1904 Fred Warren, the editor of the socialist journal, Appeal to Reason, commissioned Sinclair to write a novel about immigrant workers in the Chicago meat packing houses. Julius Wayland, the owner of the journal provided Sinclair with a $500 advance and after seven weeks research he wrote The Jungle. Serialized in 1905, the book helped to increase circulation to 175,000.

In September 1905, Sinclair helped to establish the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Other members included Jack London, Clarence Darrow, Florence Kelley, Anna Strunsky, Bertram D. Wolfe, Jay Lovestone, John Spargo, Rose Pastor Stokes and J.G. Phelps Stokes. Its stated purpose was to "throw light on the world-wide movement of industrial democracy known as socialism."

(If you find this article useful, please feel free to share. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.)

Sinclair had his novel, The Jungle, rejected by six publishers. A consultant at Macmillan wrote: "I advise without hesitation and unreservedly against the publication of this book which is gloom and horror unrelieved. One feels that what is at the bottom of his fierceness is not nearly so much desire to help the poor as hatred of the rich."

Sinclair decided to publish the book himself and after advertising his intentions in the Appeal to Reason, he he got orders for 972 copies. When he told Doubleday of these orders, it decided to publish the book. The Jungle (1906) was an immediate success selling over 150,000 copies. In the first year he received $30,000 (equivalent to $600,000 today) in royalties.

Within the next few years the novel had been published in seventeen languages and was a best-seller all over the world. Winston Churchill was one of those who praised the book. He said that Sinclair was a writer of "very great gifts". However, he rejected "Sinclair's conclusion that socialism was the answer to the problems he so convincingly described".

After President Theodore Roosevelt read The Jungle and ordered an investigation of the meat-packing industry. He also met Sinclair and told him that while he disapproved of the way the book preached socialism he agreed that "radical action must be taken to do away with the efforts of arrogant and selfish greed on the part of the capitalist."

With the passing of the Pure Food and Drugs Act (1906) and the Meat Inspection Act (1906), Sinclair was able to show that novelists could help change the law. This in itself inspired a tremendous growth in investigative journalism. Theodore Roosevelt became concerned at this development and described it as muckraking.

Helicon Home Colony

Sinclair was now a well-known national figure and decided to accept the offer of the Socialist Party to become its candidate for Congress in New Jersey. The venture was unsuccessful with Sinclair winning only 750 out of 24,000 votes.

In 1906 Sinclair decided to use some of his royalties into establishing, Helicon Home Colony, a socialist community at Eaglewood. Over the next few months, eighty people joined the community. One member was Sinclair Lewis, who was to be greatly influenced by Upton Sinclair's views on politics and literature. Four months after it opened, a fire entirely destroyed Helicon. Later, Sinclair blamed his political opponents for the fire.

Sinclair's next few novels such as The Overman (1907), The Metropolis (1908), The Moneychangers (1908) and Love's Pilgrimage (1911) were commercially unsuccessful. His marriage was also in difficulty and his wife left him for the poet Harry Kemp.

Sinclair married his second wife, Mary Craig Kimbrough in 1913. The following year the couple moved to Croton-on-Hudson, a small town close to New York City where there was a substantial community of radicals living including Max Eastman, John Reed, Louise Bryant, Floyd Dell, Robert Minor, Boardman Robinson and Inez Milholland. He also pleased his socialist friends with his anthology of social protest, The Cry for Justice (1915). John Reed wrote to Sinclair that his "anthology has made more radicals than anything I ever heard of".

First World War

Initially, members of the Socialist Party had argued that the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system and were opposed to the United States becoming involved in the conflict. However, news of the atrocities carried out by German soldiers in Belgium convinced some members that the United States should join the Allies against the Central Powers.

Sinclair took this view and began arguing this case in the radical journal, The Masses. Its editor, Max Eastman and John Reed, who had been to the Western Front and Eastern Front as a war reporter, disagreed and argued against him in the journal. The issue split the Socialist Party and eventually Sinclair resigned from the party over it.

After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917 the Espionage Act was passed and this resulted in several of Sinclair's socialist opponents, being imprisoned for their opposition to the war. Sinclair now took up their case and when Eugene Debs, was imprisoned Sinclair wrote to Woodrow Wilson arguing that it was "futile to try and win democracy abroad, while we are losing it at home."

Sinclair continued to write political committed novels including King Coal (1917) based on an industrial dispute. He also wrote books about religion (The Profits of Religion, 1918), newspapers (The Brass Check, 1919) and education (The Goose-Step, 1923 and The Goslings, 1924). Arthur Conan Doyle claimed that "I look upon Upton Sinclair as one of the greatest novelists in the world, the Zola of America."

Sacco and Vanzetti

Upton Sinclair joined John Dos Passos, Alice Hamilton, Paul Kellog, Jane Addams, Heywood Broun, William Patterson, Dorothy Parker, Ben Shahn, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Felix Frankfurter, John Howard Lawson, Freda Kirchway, Floyd Dell, Bertrand Russell, George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells in the campaign to free Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. After they were executed on 23rd August 1927, Sinclair decided to investigate the case. He interviewed Fred Moore, one of defence lawyers in the case. According to Sinclair's latest biographer, Anthony Arthur: "Fred Moore, Sinclair said later, who confirmed his own growing doubts about Sacco's and Vanzetti's innocence. Meeting in a hotel room in Denver on his way home from Boston, he and Moore talked about the case. Moore said neither man ever admitted it to him, but he was certain of Sacco's guilt and fairly sure of Vanzetti's knowledge of the crime if not his complicity in it."

A letter written by Sinclair at the time acknowledged that he had doubts about Moore's testimony: "I realized certain facts about Fred Moore. I had heard that he was using drugs. I knew that he had parted from the defense committee after the bitterest of quarrels.... Moore admitted to me that the men themselves had never admitted their guilt to him, and I began to wonder whether his present attitude and conclusions might not be the result of his brooding on his wrongs."

Sinclair was now uncertain if a miscarriage of justice had taken place. He decided to end the novel on a note of ambiguity concerning the guilt or innocence of the Italian anarchists. When Robert Minor, a leading figure in the American Communist Party, discovered Sinclair's intentions he telephoned him and said: "You will ruin the movement! It will be treason!" Sinclair's novel, Boston, appeared in 1928. Unlike some of his earlier radical work, the novel received very good reviews. The New York Times called it a "literary achievement" and that it was "full of sharp observation and savage characterization," demonstrating a new "craftsmanship in the technique of the novel".

Sinclair wrote at the time: "In the course of my twenty years career as an assailant of special privilege, I have attacked pretty nearly every important interest in America. The statements I have made, if false, would have been enough to deprive me of a thousand times all the property I ever owned, and to have sent me to prison for a thousand times a normal man's life. I have been called a liar on many occasions, needless to say; but never once in all these twenty years has one of my enemies ventures to bring me into a court of law, and to submit the issue between us to a jury of American citizens." In 1926 Arthur Conan Doyle argued: "I look upon Upton Sinclair as one of the greatest novelists in the world, the Zola of America."

Socialist Party Candidate

Sinclair rejoined the Socialist Party and in 1926 was its candidate to become governor of California. The following year he wrote an article for The Nation where he admitted he had been wrong about the First World War. In 1934 Sinclair once again stood as a candidate to become governor. As William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963), pointed out: "Sinclair proposed a direct attack on the crucial problem the New Deal was not solving: want in the midst of plenty. Instead of placing idle workers on relief, he urged that they be given a chance to produce for their own needs. The state would buy or lease lands on which the jobless could grow their own food; it would rent idle factories in which unemployed workers could turn out staples like clothing and furniture."

Once again, not one of the seven hundred daily newspapers in California supported Sinclair. They reported that Sinclair had told Harry Hopkins: "If I am elected, half of the unemployed will come to California, and you will have to take care of them." Movie companies turned out "newsreels" showing armies of hoboes crossing state borders into California.

Even supporters of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal came out against Sinclair. One of these commented that Sinclair was a "communistic wolf in the dried skin of the Democratic donkey." Leading figures in the Democratic Party called for their members to vote for the conservative Republican Party candidate, Frank Merriam. Sinclair stood no chance against this campaign of vilification and obtained only 879,537 votes against Merriam's 1,138,620.

Jerry Voorhis, who helped him with his campaign, later remarked: "He was a dedicated, determined, somewhat proud man. He lacked the personal warmth of most successful politicians. His intellect and the logic of his plan were to carry his campaign. Sinclair's small size seemed only to accentuate the piercing power of his eyes, and reinforce the finality of his decisions. Through his spectacles he looked clear through you, as if he were undressing you, at least, intellectually. He was austere and puritanical in his personal habits. He was the friend of all who joined him in his fiery zeal to expose all the wrongs of society. But hardly a warm friend or one with whom one looked forward to spending a relaxed evening over Coca-Cola."

Upton Sinclair became ore conservative as he grew older. This brought him into conflict with his only son, David Sinclair. He told his father, "I wish you'd go back and read all your books again and become converted by them." He was also critical of his father's support for Joseph Stalin during the Great Purges. He found it difficult to understand how his father could believe the confessions made by former Bolsheviks. Sinclair replied that he was "unable to believe that those men would have confessed unless they were guilty... most Russian revolutionaries stood the torture of the Czarist police for the faith, and they would do it today if the charges were frame-ups."

World's End

In 1940 World's End launched Sinclair's 11 volume novel series on modern politics. The main character was a spy named Lanny Budd. It has been argued that the character is based on two of his friends, Cornelius Vanderbilt and Albert Birnbaum. The first book in the series, World's End, sold over 500,000 copies.

His novel Dragon's Teeth (1942) on the rise of Nazi Germany won him the Pulitzer Prize. The British author, George Bernard Shaw, wrote at the time: "I have regarded you (Upton Sinclair), not as a novelist, but as an historian; for it is my considered opinion, unshaken at 85, that records of fact are not history... When people ask me what has happened in my long lifetime I do not refer them to the newspaper files and to the authorities, but to your novels. The object that the people in your books never existed; that their deeds were never done and their sayings never uttered. I assure them that they were, except that Upton Sinclair individualized and expressed them better than they could have done, and arranged their experiences, which as they actually occurred were as unintelligible as pied type, in significant and intelligible order."

Mary Craig Kimbrough suffered from depression. In one letter she wrote: "Life is not ever the delightful thing we all imagine it is when we are young. I have never known a really happy person who had passed the age of fifty! By that time the hopes of youth had turned into the realities of life - and hopes are thus crushed, one by one." She died on on 26th April, 1961. Six months later Sinclair married his third wife, Mary Elizabeth Willis.

By the time Upton Sinclair died at a small nursing home in Bound Brook, New Jersey, on 18th December, 1968, he had published more than ninety books.

Primary Sources

(1) In American Outpost, Upton Sinclair explained the writing of his first successful novel, The Jungle.

I wrote with tears and anguish, pouring into the pages all that pain which life had meant to me. Externally the story had to do with a family of stockyard workers, but internally it was the story of my own family. Did I wish to know how the poor suffered in winter time in Chicago? I only had to recall the previous winter in the cabin, when we had only cotton blankets, and had rags on top of us. It was the same with hunger, with illness, with fear. Our little boy was down with pneumonia that winter, and nearly died, and the grief of that went into the book.

(2) Upton Sinclair, Cosmopolitan (October, 1906)

What life means to me is to put the content of Shelley into the form of Zola. The proletarian writer is a writer with a purpose; he thinks no more of "art for art's sake" than a man on a sinking ship thinks of painting a beautiful picture in the cabin; he thinks of getting ashore - and then there will be time enough for art.

(3) Upton Sinclair, The Jungle (1906)

It was only when the whole ham was spoiled that it came into the department of Elzbieta. Cut up by the two-thousand-revolutions-a-minute flyers, and mixed with half a ton of other meat, no odor that ever was in a ham could make any difference. There was never the least attention paid to what was cut up for sausage; there would come all the way back from Europe old sausage that had been rejected, and that was moldy and white - it would be dosed with borax and glycerine, and dumped into the hoppers, and made over again for home consumption. There would be meat that had tumbled out on the floor, in the dirt and sawdust, where the workers had tramped and spit uncounted billions of consumption germs. There would be meat stored in great piles in rooms; and the water from leaky roofs would drip over it, and thousands of rats would race about on it. It was too dark in these storage places to see well, but a man could run his hand over these piles of meat and sweep off handfuls of the dried dung of rats. These rats were nuisances, and the packers would put poisoned bread out for them; they would die, and then rats, bread, and meat would go into the hoppers together. This is no fairy story and no joke; the meat would be shoveled into carts, and the man who did the shoveling would not trouble to lift out a rat even when he saw one - there were things that went into the sausage in comparison with which a poisoned rat was a tidbit. There was no place for the men to wash their hands before they ate their dinner, and so they made a practice of washing them in the water that was to be ladled into the sausage. There were the butt-ends of smoked meat, and the scraps of corned beef, and all the odds and ends of the waste of the plants, that would be dumped into old barrels in the cellar and left there. Under the system of rigid economy which the packers enforced, there were some jobs that it only paid to do once in a long time, and among these was the cleaning out of the waste barrels. Every spring they did it; and in the barrels would be dirt and rust and old nails and stale water - and cartload after cartload of it would be taken up and dumped into the hoppers with fresh meat, and sent out to the public's breakfast. Some of it they would make into "smoked" sausage but as the smoking took time, and was therefore expensive, they would call upon their chemistry department, and preserve it with borax and color it with gelatine to make it brown. All of their sausage came out of the same bowl, but when they came to wrap it they would stamp some of it "special," and for this they would charge two cents more a pound.

(4) Upton Sinclair, in an interview with Rene Fulop-Miller (24th March, 1923)

I am a person who has never used violence himself. My present opinion is that people who have obtained the ballot should use it and solve their problems in that way. In the case of peoples who have not obtained the ballot, and who cannot control their states, I again find in my own mind a division of opinion, which is not logical, but purely a rough practical judgment. My own forefathers got their political freedom by violence; that is to say, they overthrew the British crown and made themselves a free Republic. Also by violence they put an end to the enslavement of the black race on this continent.

(5) Upton Sinclair, letter to the Anti-Enlistment League (20th September, 1915)

I know you are brave and unselfish people, making sacrifices for a great principle but I cannot join you. I believe in the present effort which the allies are making to suppress German militarism. I would approve of America going to their assistance. I would enlist to that end, if ever there be a situation where I believe I could do more with my hands than I could with my pen.

(6) Upton Sinclair, letter of resignation from the Socialist Party (September, 1917)

I have lived in Germany and know its language and literature, and the spirit and ideals of its rulers. Having given many years to a study of American capitalism. I am not blind to the defects of my own country; but, in spite of these defects, I assert that the difference between the ruling class of Germany and that of America is the difference between the seventeenth century and the twentieth.

No question can be settled by force, my pacifist friends all say. And this in a country in which a civil war was fought and the question of slavery and secession settled! I can speak with especial certainty of this question, because all my ancestors were Southerners and fought on the rebel side; I myself am living testimony to the fact that force can and does settle questions - when it is used with intelligence.

In the same way I say if Germany be allowed to win this war - then we in America shall have to drop every other activity and devote the next twenty or thirty years to preparing for a last-ditch defence of the democratic principle.

(7) Upton Sinclair, letter to John Reed (22nd October, 1918)

American capitalism is predatory, and American politics are corrupt: The same thing is true in England and the same in France; but in all these three countries the dominating fact is that whatever the people get ready to change the government, they can change it. The same thing is not true of Germany, and until it was made true in Germany, there could be no free political democracy anywhere else in the world - to say nothing of any free social democracy. My revolutionary friends who will not recognize this fact seem to me like a bunch of musicians sitting down to play a symphony concert in a forest where there is a man-eating tiger lose. For my part, much as I enjoy symphony concerts, I want to put my fiddle away in its case and get a rifle and go out and settle with the tiger.

(8) Upton Sinclair, The Brass Check (1919)

In the course of my twenty years career as an assailant of special privilege, I have attacked pretty nearly every important interest in America. The statements I have made, if false, would have been enough to deprive me of a thousand times all the property I ever owned, and to have sent me to prison for a thousand times a normal man's life. I have been called a liar on many occasions, needless to say; but never once in all these twenty years has one of my enemies ventures to bring me into a court of law, and to submit the issue between us to a jury of American citizens.

(9) Upton Sinclair, letter to the Los Angeles Police Chief (7th April, 1928)

I am not a giant physically; I shrink from pain and filth and vermin and foul air, like any other man of refinement; also, I freely admit that when I see a line of a hundred policeman with drawn revolvers flung across a street to keep anyone from coming on to private property to hear my feeble voice. But I have a conscience and a religious faith, and I know that our liberties were not won without suffering, and may be lost again through our cowardice.

(10) Upton Sinclair, Boston (1928)

There was John Dos Passos, faithful son of Harvard, and John Howard Lawson, another one of the 'New Playwrights' from Greenwich Village. There was Clarina Michelson, ready to do the hard work again, and William Patterson, a Negro lawyer from New York, running the greatest risk of any of them, with his black face not to be disguised. Just up Beacon Street was the Shaw Monument, with figures in perennial bronze, of unmistakable Negro boys in uniforms, led by a young Boston blueblood on horseback; no doubt Patterson had looked at this, and drawn courage from it. ...

The trooper speeds on; he has spied the black face, and wants that most of all. The Negro runs, and the rider rears the front of his steed, intending to strike him down with the iron-shod hoofs. But fortunately there is a tree, and the Negro leaps behind it; and a man can run around a tree faster than the best-trained police-mount - the dapper and genial William Patterson proves it by making five complete circuits before he runs into the arms of an ordinary cop, who grabs him by the collar and tears off his sign and tramples it in the dirt, and then starts to march him away. 'Well,' he remarks sociably, 'This is the first time I ever see a ****** bastard that was a communist.' The lawyer is surprised, because he has been given to understand that that particular word is barred from the Common. Mike Crowley was so shocked, two weeks ago, when Mary Donovan tacked up a sign to a tree: 'Did you see what I did to those anarchistic bastards? - Judge Thayer.' But apparently the police did not have to obey their own laws.

(11) Sinclair Lewis, wrote a letter to Upton Sinclair where he pointed out a long list of factual inaccuracies in his book, Money Writes!, (3rd January, 1928)

I did not want to say these unpleasant things, but you have written to me, asking my opinion, and I give it to you, flat. If you would get over two ideas - first that any one who criticizes you is an evil and capitalist-controlled spy, and second that you have only to spend a few weeks on any subject to become a master of it - you might yet regain your now totally lost position as the leader of American socialistic journalism.

(12) The Nation, review of Oil (5th December, 1927)

What Fielding was to the eighteenth century and Dickens to the nineteenth. Sinclair is to our own. The overwhelming knowledge and passionate expression of specific wrongs are more stirring, more interesting, and also more taxing than the cynical censure of Fielding and the sentimental lamentations of Dickens.

(13) H. L. Mencken, letter to Upton Sinclair (2nd May, 1936)

You have been making reckless charges against all sorts of people ... and yet you set up a horrible clatter every time you are put on the block yourself.... No man in history has denounced more people than you have, or in more violent terms, and yet no man that I can recall complains more bitterly when he happens to be hit. Why not stop your caterwauling for a while, and try to play the game according to the rules?

(14) H. L. Mencken, letter to Upton Sinclair published in The American Mercury (June, 1936)

You protest, and with justice, each time Hitler jails an opponent; but you forget that Stalin and company have jailed and murdered a thousand times as many. It seems to me, and indeed the evidence is plain, that compared to the Moscow brigands and assassins. Hitler is hardly more than a common Ku Kluxer and Mussolini almost a philanthropist.

(15) George Bernard Shaw, (12th December, 1941)

I have regarded you (Upton Sinclair), not as a novelist, but as an historian; for it is my considered opinion, unshaken at 85, that records of fact are not history. They are only annals, which cannot become historical until the artist-poet-philosopher rescues them from the unintelligible chaos of their actual occurrence and arranges them in works of art.

When people ask me what has happened in my long lifetime I do not refer them to the newspaper files and to the authorities, but to your novels. The object that the people in your books never existed; that their deeds were never done and their sayings never uttered. I assure them that they were, except that Upton Sinclair individualized and expressed them better than they could have done, and arranged their experiences, which as they actually occurred were as unintelligible as pied type, in significant and intelligible order.

(16) Upton Sinclair, letter to Norman Thomas (25th September, 1951)

The American People will take Socialism, but they won't take the label. I certainly proved it in the case of EPIC. Running on the Socialist ticket I got 60,000 votes, and running on the slogan to "End Poverty in California" I got 879,000. I think we simply have to recognize the fact that our enemies have succeeded in spreading the Big Lie. There is no use attacking it by a front attack, it is much better to out-flank them.

(17) Anthony Arthur, Radical Innocent: Upton Sinclair (2006)

A more pertinent critique of Sinclair's career, one seldom heard, might have questioned the wisdom of devoting most of his life to a goal that never stood a chance of being reached in the United States -socialism - because its premise, the essential iniquity of capitalism, was one that most Americans would never share.

But that objection too would miss the point. Socialism, whatever its other faults or merits might be, served Sinclair very well indeed. He knew that he was not naturally "sweet and kind." He was not introspective -unusual for a writer - but he was self-centered and rigidly intolerant of frailty in others. His genial public image is often belied by the private self revealed in his letters and in his books, right up to the end of his life. His fundamental nature remained that of the driven artist. Even after he became a socialist reformer, he was largely responsible for the failure of his first marriage and for the decades of estrangement from his son during his second. He wrote so often about re-enacting Christ's temptation in the wilderness that the temptations, though resisted, must have been real for him.

What saved Sinclair - what made him, in the end, a happy and contented man was his conversion from the religion of art to the religion of socialism, which he called the religion of humanity. The religion of art is essentially selfish, at least as it is usually conceived of today. Socialism, for Sinclair, was essentially selfless. It allowed him to make himself into a better person, and to do the work that would bring him fulfillment.

The true significance of Sinclair's often derided puritanism finally becomes apparent when viewed in the light of his socialism. He was a puritan in the sense of Bunyan's Christian, searching for the true path to salvation. Socialism gave him that path. He was also a Romantic idealist who lived as though the journey, not the destination, was what mattered.