Julius Wayland

Julius Wayland was born in Versailles, Indiana, on 26th April, 1854. Four months after being born a cholera epidemic took the lives of his father and four of his brothers and sisters. The surviving members of the family lived in abject poverty and after two years schooling, Wayland was forced to find work.

Wayland was employed as a printer's apprentice on the Versailles Gazette. After learning the trade he worked for neighboring newspapers as a printer and typesetter. By 1872 Wayland had saved enough money to become a part owner of the newspaper. Two years later he became its sole proprietor and eventually turned it into a highly profitable newspaper.

Wayland became converted to socialism after reading books such as The Cooperative Commonwealth: An Exposition of Modern Socialism (Laurence Gronlund) and Looking Backward (Edward Bellamy). When he expressed these views in his newspaper he so upset the conservatives in the town that a mob put a rope around his neck and talked about lynching him.

After this incident Wayland decided to move to Pueblo, Colorado. In April, 1893, Wayland began publishing the radical journal, The Coming Nation. Within fifteen months the journal had a circulation of 60,000 and was the most popular socialist newspaper in America. With the profits from the newspaper Wayland helped to fund a utopian colony, the Ruskin Co-operative Association, on 2,000 acres of land near Tennessee City.

Named after one of his his heroes, John Ruskin, Wayland wrote that he intended to provide "every convenience that the rich enjoy, permanent employment at wages higher than ever dreamed of by laborers, with all the advantages of good schools, free libraries, natatoriums, gymnasiums, lecture halls and pleasure grounds." He added that "one practical success showing that man can live and love in peace and plenty, will do more about bringing the Brotherhood of Man than a thousand speakers."

Wayland had difficulty making his community work and in July, 1895, he left Ruskin after handing over his land and The Coming Nation to the Ruskin Co-operative Association. He settled in Missouri, and in August, 1895, began publishing the socialist journal, Appeal to Reason. The journal was a mixture of articles and extracts from radical books by people such as Tom Paine, Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, John Ruskin, William Morris, Laurence Gronlund and Edward Bellamy.

Wayland moved to Girard, Kansas, and in 1900 employed Fred Warren as his co-editor. Warren was a well-known figure on the left and managed to persuade some of America's leading progressives to contribute to the Appeal to Reason. This included Jack London, Mary 'Mother' Jones, Upton Sinclair, Scott Nearing, Joe Haaglund Hill, Kate Richards O'Hare, Ralph Chaplin, Stephen Crane, Helen Keller and Eugene Debs. By 1902 its circulation reached 150,000, making it the fourth highest of any weekly in the United States.

In 1904 Warren commissioned Upton Sinclair to write a novel about immigrant workers in the Chicago meat packing houses. Wayland provided Sinclair with a $500 advance and after seven weeks research he wrote the novel, The Jungle. Serialized in 1905, the book helped to increase circulation to 175,000. When published by Doubleday in 1906, the novel was an immediate success. Within the next few year it was published in seventeen languages and was a best-seller all over the world.

In 1905 William Hayward (general secretary of WFM) and Charles Moyer (president of WFM), were both been kidnapped in Colorado and taken to Idaho to stand trial for the murder of Frank R. Steunenberg, the former governor of Idaho. This upset Warren as a few years earlier the authorities had refused to arrest and charge William S. Taylor, the former governor of Kentucky, with the murder of the progressive politician, William Goebel. Taylor fled to Indiana where he became a wealthy insurance executive.

Fred Warren wrote an article about the William Goebel case in Appeal to Reason and advertised a reward of $1,000 for anyone willing to capture William S. Taylor and to take him back to Kentucky. As a result of this article Warren was himself arrested and charged with encouraging others to commit the crime of kidnap. After a two year delay was found guilty and sentenced to six months hard labour and a $1,500 fine. Soon afterwards the governor of Kentucky, Augustus Everett Willson, pardoned Taylor, Caleb Powers, and four other people for their part in the murder.

Wayland and Warren were once again in trouble in 1911 when they published a series of articles in the Appeal to Reason about corruption and homosexuality in Leavenworth Prison. Although senior figures running the prison were dismissed, Wayland and Warren were charged were charged with sending "indecent, filthy, obscene, lewd and lascivious printed materials" through the post.

As the popularity of the Appeal to Reason increased, so did the attacks on Wayland and Warren. The paper's offices were repeatedly broken into in an effort to find evidence of criminal activity. Research was carried out about Wayland's ancestors and reports in the Los Angeles Times claiming that they had been involved in cases of arson and murder. In 1912 the newspaper reported that Wayland was guilty of seducing an orphaned girl of fourteen and who had died during an abortion in Missouri.

Julius Wayland, depressed by the recent death of his wife and the continuing smear campaign against him, committed suicide on 10th November, 1912. He left a suicide note that said: "The struggle under the competitive system is not worth the effort." After Wayland's death his children won considerable damages after they sued the newspapers about these libelous stories.

Primary Sources

(1) Julius Wayland, Appeal to Reason (18th November, 1899)

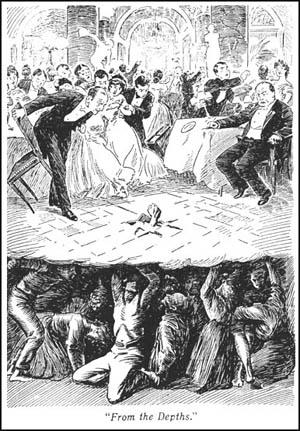

A great many people believe that they know what socialism means, but they do not. They vainly imagine that it refers to bursting bombs, burning buildings, rapine and plunder. But those folks have never looked for the definition in Webster's dictionary which says that socialism is: "A theory of society that advocates a more precise, orderly and harmonious arrangement of the social relations of mankind than that which has hitherto prevailed."

Of course that does not sound so very bad. Still for fear that Noah Webster may have been out of his head when defining socialism, let us go to some other authority and read carefully the definition in the Standard dictionary, which says that socialism is: "A theory of policy that aims to secure the reconstruction of society, increase of wealth, and a more equal distribution of the products of labor through the public collective ownership of labor and capital (as distinguished from property) and the public collective management of all industries."

Maybe things have changed since Noah Webster died. We have it here. The Century dictionary defines socialism as: "Any theory or system of local organization which would abolish entirely, or in a greater part, the individual effort and competition on which modern society rests, and substitute co-operation; would introduce a more perfect and equal distribution of the products of labor; and would make land and capital, as the instruments of production, the joint possessions of the community."

Then, again, there are our religious friends who have vaguely, but wrongly, believed that socialism was the enemy of religion. What have you to say of this statement made by the Encyclopedia Britannica? "The ethics of socialism are identical with the ethics of Christianity."

(2) Julius Wayland, Appeal to Reason (5th January, 1906)

When I look at the ferment of this insane social system; when I see its corruption, bribery, oppression, suicides, murders, robberies, prostitution, drunkenness and rapid concentration of wealth; when I see the masses apparently dead asleep to the meaning of their condition or to what is tending; when I see the rulers taking to themselves more power while the millions gradually let slip their influence in public affairs; when I see the courts more and more becoming only tools for the rich, while the poor are helpless before the law; when I see the voters losing what little comprehension they had of the purpose of the ballot, using it merely as a means to favor some scheming, cunning, self-seeking friend with a fat place; when I see the great corporations corralling the lands in great tracts, filling the waterways with their own ships and exploiting the riches of the mines for their kingly self-aggrandizement; I say, when I look over this alleged civilization and see these things, I feel a hopelessness that makes me heart-sick, and I wonder if it is worth the struggle, and if life is worth its care and if annihilation were not a joy.

Then, there is another view, I remember how I felt when I received my first impression of the social system as it is. I woke up as from a dream, and beheld the horrors about me stripped of their flimsy covering and nauseating in their nakedness. I had caught a glimpse of a higher, delightful harmoniousness; and it was so beautiful, so just, that I felt all would accept it as soon as they were told of it; that the present hateful thing could all be remodeled in a few years; that people would flock to the New Civilization as soon as they would read or hear of it. At that time there were no papers or magazines to tell the beautiful story; no books to explain it, except a few academically written volumes on out-of-the-way shelves in public libraries - books which nobody read.

I threw myself into the work of getting the message to the people with a wild delirium of enthusiasm; I read, and talked, and wrote, and printed and circulated the printed page; I stood on the street corners and handed the passers a leaflet or pamphlet; I mailed copies to thousands of names without considering the character of the recipients; I put years of life and energy into a few months. Gradually it began to dawn on me that the job was greater than I had felt in my first enthusiasm; I had been too optimistic; it would take years of persistent, systematic work; a siege must be laid to the inertia and ignorance of the masses.

(3) Jon Wayland, later recalled his last conversation with his father before he committed suicide on 10th November, 1912.

"My boy, I am going to end it all; I cannot longer stand this persecution, mental oppression and misunderstanding. I have done my work living and worn myself out, and perhaps my death will further the interests of the cause." I remonstrated with him, but to no avail. He said, "It will do no good to argue for I have made up my mind." Not once during this talk did he exhibit my feeling of malice or hatred toward even those government officials who are directly responsible for the death. He felt it was all a part of the order of life and unavoidable.

(4) Kate Richards O'Hare, letter to the Appeal to Reason on the death of Julius Wayland (23rd November, 1912)

We have no idle, vain, regrets; for who are we to judge, or say that he has shirked his task or left some work undone? No eyes can count the seed that he has sown, the thoughts that he has planted in a million souls now covered deep beneath the mold of ignorance which will not spring into life until the snows have heaped upon his grave and the sun of springtime comes to reawake the sleeping world.

Sleep on, our comrade; rest your weary mind and soul; sleep and deep, and if in other realms the boon is granted that we may again take up our work, you will be with us and give us your strength, your patience and your loyalty to your fellow men. We bring no ostentartious tributes of our love, we spend not gold for flowers for your tomb, but with hearts that rejoice at your deliverance offer a comrade's tribute to lie above your breast - the red flag of human brotherhood.